Abstract

The performance of polycrystalline Ge thin films, anticipated for application in advanced electronic and optical devices, has markedly improved in recent years. However, the high density of acceptor defects in Ge complicates Fermi level control, impeding device applications. This study explores defect passivation by incorporating hydrogen atoms into recently developed high-quality polycrystalline Ge thin films. Hydrogen introduced to Ge through plasma processes forms Ge-H bonds in large-grained Ge layers, in contrast to conventional small-grained Ge layers where this bonding does not occur. Increasing Ge-H bonding correlates with a reduction in defect-induced hole concentration from 1017 cm−3 to the order of 1015 cm−3, representing the lowest reported hole concentration for polycrystalline Ge layers. Low-temperature annealing after hydrogenation further decreases the hole concentration while improving the hole mobility. These findings indicate that hydrogen atoms in Ge passivate both acceptor defects and grain boundary carrier traps. The resulting Ge layer achieves high hole mobility (170 cm2 V−1 s−1) and low hole concentration (4 × 1014 cm−3), an accomplishment unattainable with conventional polycrystalline group IV semiconductor thin films, paving the way for implementing polycrystalline Ge-based thin films in semiconductor devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Germanium has regained attention as a material for next-generation electronics due to its excellent electrical and optical properties. Ge-on-insulator structures are crucial for advanced Ge-based transistors1,2,3, solar cells4,5, optical communications6,7,8, and thermoelectric devices9,10. While mechanical transfer methods yield high-quality Ge-on-insulator structures11,12, the complexity of the process limits its application. Consequently, Ge thin films have been synthesized directly on insulators using various techniques. Single-crystalline Ge layers are formed through oxidation-induced condensation13,14, rapid melting15,16,17,18, and epitaxial growth on Si-on-insulator19. Low-temperature synthesis of polycrystalline Ge layers has been explored using solid-phase crystallization20,21,22,23, laser annealing24,25,26,27,28,29, chemical vapor deposition30,31,32, lamp annealing33,34,35, plasma irradiation36, seed layer technique37, and metal-induced crystallization38,39,40,41,42,43. Notably, recent progress in low-temperature solid-phase crystallization has seen remarkable success. Modulating the deposition temperature (Td) of the precursor amorphous Ge layer and adding impurities significantly increased grain size in resulting polycrystalline Ge layers44,45,46. Carrier mobility reached peak values (690 and 450 cm2 V−1 s−1 for holes and electrons, respectively) for polycrystalline Ge films, even on a glass and flexible plastic substrates47,48. These carrier mobilities are higher than those of Ge thin films epitaxially grown on single-crystal Si substrates19.

The primary challenge of employing Ge layers in semiconductor devices is the presence of acceptor defects49,50. The high hole concentration (p) in the range of 1017–1019 cm−3, attributed to acceptor defects in Ge thin films, complicates Fermi level control, critical in fabricating most semiconductor devices. For instance, in thin-film transistors utilizing Ge as a channel, high leakage currents due to elevated p have been problematic51,52. Studies have sought to reduce p by adding group IV elements, such as Sn53,54,55,56 and Si57,58,59, to Ge. We achieved a reduction in p to the order of 1016 cm−3 using solid-phase crystallization of GeSn, the lowest reported value for a Ge-on-insulator structure formed by crystal growth and even lower than a single-crystal Ge layer56. While SiGe can reduce p by increasing Si composition, hole mobility (μ) has remained below 50 cm2 V−1 s−1, due to increased effective mass and grain boundary barrier height58. Achieving both low p and high μ in polycrystalline group-IV semiconductor thin films has proven challenging.

Hydrogen atom addition is a common method for compensating defects in semiconductors. In polycrystalline Si thin films, hydrogen passivates defects, leading to significantly improved electrical properties60,61. Hydrogen is also effective in reducing p in silicide semiconductors, where defects act as acceptors62. There have been some experimental reports of hydrogen effects on Ge, including surface modification21,63,64. However, hydrogen has not produced a positive effect on the electrical properties of Ge, which has been supported as reasonable by theoretical studies65. This study investigates the effect of hydrogen addition on solid-phase crystallized Ge layers, updating the highest carrier mobility. Hydrogen considerably deactivated acceptor defects in high-quality Ge layers, while no effect was observed in conventional Ge layers. Controlled hydrogen addition and heat treatment conditions reduced p to 1014 cm−3, two orders of magnitude less than the lowest conventional value, while maintaining high μ in the polycrystalline Ge layers.

Results

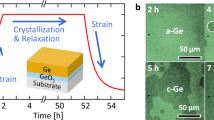

Figure 1a is a schematic of the sample preparation process. Amorphous Ge layers were deposited on SiO2 glass substrates using a Knudsen cell in a molecular beam deposition system. Subsequently, the samples were annealed to induce solid-phase crystallization. This process resulted in the formation of polycrystalline Ge layers on the glass substrates. Hydrogen was then introduced to the polycrystalline Ge layers using a plasma generator with a mixed gas of Ar and H2. Figure 1b shows that the Ge layers are uniformly formed on glass substrates. For both Td = 50 and 125 °C samples, the appearance changes from dark before crystallization to reddish after crystallization. This is because the amorphous state absorbs light more effectively, whereas the crystalline state does not absorb long-wavelength light, which is instead reflected. No color differences are observed due to hydrogen irradiation or Td, suggesting that these parameters do not affect the fundamental properties such as the band structure.

Figure 2a and b illustrate that the grain size of the Ge layer after annealing strongly depended on Td. The Td = 125 °C sample exhibited a grain size more than one order of magnitude larger than that of the Td = 50 °C sample. The Td dependence can be explained in terms of the atomic density of the amorphous precursors (Fig. S1)45. For both Td = 50 and 125 °C, the Ge layer is in an amorphous state at the time of deposition. A low-density amorphous Ge layer is formed at Td = 50 °C (Fig. S1(a)), whereas a high-density amorphous Ge layer is formed at Td = 125 °C (Fig. S1(b)). For the low-density amorphous Ge, because the atomic spacing is large, another nucleation occurs before lateral growth progresses, resulting in numerous grain boundaries and small grains. Conversely, the high-density precursor undergoes rapid lateral growth before another nucleation event, producing larger grains with fewer boundaries. Thus, Td = 125 °C produces large-grained poly-Ge with high crystallinity, leading to superior electrical performance. According to the EBSD measurement, hydrogen plasma irradiation did not affect the grain size of the Ge layer (Fig. S2). Figure 2c and d demonstrates that the effect of plasma treatment on the electrical properties varies dramatically with Td. For the Td = 50 °C sample, both p and μ decreased slightly with increasing hydrogen plasma irradiation time (tH). The decrease in p suggests the passivation of acceptor defects by hydrogen. As in general polycrystalline semiconductor thin films, the µ of the current Ge layers is mostly limited by the grain boundary scattering of carriers45,54. Therefore, the decrease in µ with decreasing p is reasonable since the grain boundary barrier is higher at lower p66. The effect of hydrogen plasma irradiation was more pronounced for Td = 125 °C: p decreased dramatically with increasing tH, reaching the order of 1015 cm−3. The degree of the decrease increased with increasing plasma power (WP). These observations suggest that hydrogen plasma treatment effectively passivated acceptor defects in the high-quality polycrystalline Ge layer. The μ value of the Td = 125 °C sample initially decreased and then increased with increasing tH. The fact that µ improves while p decreases suggests that plasma treatment has reduced grain boundary carrier traps. Thus, hydrogen plasma treatment had little effect on conventional low-quality polycrystalline Ge layers, whereas it exhibited a dramatic acceptor defect compensation effect on high-quality polycrystalline Ge layers.

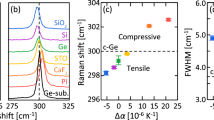

We investigated the hydrogen state in polycrystalline Ge layers. As shown in Fig. 3a, secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) measurement reveals that hydrogen is present with a concentration gradient in the depth direction of the Ge layer. The Td = 50 °C sample showed a higher hydrogen concentration than that of the Td = 125 °C sample. This result is reasonable given that the Td = 50 °C samples have a high grain boundary density (Fig. 2a) because impurities generally diffuse faster at the grain boundaries than in the crystal. However, Fig. 3b shows that there was no change in the Raman spectra before and after plasma treatment for the Td = 50 °C sample, while the Raman peaks due to the bonding of Ge and H (Ge-H at 1987 cm−1, Ge-H2 at 2020 cm−1, and Ge-H3 at 2060 cm−1) were observed for the Td = 125 °C sample67. Figure 3c demonstrates that the hydrogen concentration in Ge increases with increasing WP. At a WP of 450 W, the hydrogen concentration peaked at approximately 10 nm from the surface of the Ge layer. This behavior suggests the formation of platelet defects due to the excessive penetration of hydrogen atoms68, which may contribute to the μ drop in Fig. 2d at a WP of 450 W. Figure 3d shows Raman peaks due to Ge-H bonding were observed in all samples with tH ≥ 5 min. The Raman peaks depend on tH: only the Ge-H peak for tH = 5 min, a peak attributed to Ge-H and Ge-H2 for tH = 10 min, and a broad peak that appears to be a combination of Ge-H, Ge-H2, and Ge-H3 for tH = 20 min. This behavior suggests that the number of hydrogen bonds per Ge atom increases with increasing hydrogen concentration in Ge. When considered in conjunction with the p behavior shown in Fig. 2c, the more pronounced the bonding between Ge and H, the more p is reduced, strongly suggesting that hydrogen atoms passivated the acceptor defects in Ge.

a SIMS depth profiles of hydrogen concentration and (b) Raman spectra for the Ge layers with Td = 50 °C and 125 °C, where WP = 300 W and tH = 20 min. c WP dependence of the SIMS depth profiles of hydrogen concentration for the Ge layers with Td = 125 °C, where tH = 20 min. d tH dependence of Raman spectra for the Ge layers with Td = 125 °C, where WP = 300 W.

The Raman measurement revealed that distinct Ge–H bonds were observed in high-quality (large-grain) Ge films, whereas no clear Ge–H signals were detected in low-quality (small-grain) films. This contrast can be attributed to both structural and electronic factors. In high-crystallinity Ge films, the well-ordered lattice structure provides a favorable environment for the formation of stable Ge–H bonds. In contrast, low-crystallinity films contain a high density of grain boundaries and structural defects, where hydrogen atoms are likely to be trapped. This trapping may inhibit the formation of stable Ge–H bonds. Moreover, differences in grain boundary density may also affect hydrogen diffusion behavior; in high-quality films, hydrogen is more likely to remain within the crystalline lattice, thereby promoting Ge–H bond formation. Furthermore, it has been reported that hydrogen in Ge exists predominantly in a negatively charged state (H−)65. The stability of this H− state strongly depends on the local electronic environment. In high-crystallinity films, the periodic potential and electronic uniformity provide favorable conditions for the stabilization of H− species, enabling the formation of stable Ge–H bonds. However, in low-quality films, potential fluctuations and local electronic disorder at grain boundaries and defects may destabilize the H− state. As a result, Ge–H bond formation may be suppressed, or such bonds, even if formed, may not exist in a sufficiently stable configuration to be detected. These findings suggest that the presence or absence of Ge–H bonds in Ge thin films is not only governed by the structural quality of the films, but also closely related to the charge state of hydrogen and its electronic stability within the host lattice.

We subjected Td = 125 °C samples, treated with hydrogen plasma, to low-temperature post-annealing (PA). Figure 4a shows the dependence of the electrical properties on the PA temperature (TPA). For TPA = 100 °C, no change in the electrical properties was observed compared to those before PA. In contrast, for TPA = 200 °C, p decreased by one order of magnitude to 4 × 1014 cm−3 while maintaining μ. The p value increased significantly for TPA = 300 °C, while both p and μ reverted entirely to their pre-plasma treatment values for TPA = 400 °C. These outcomes suggest that PA at suitable temperatures enhances the passivation of acceptor defects and grain boundary carrier traps, whereas PA at higher temperatures results in hydrogen desorption from Ge. For the Td = 50 °C sample, the low-temperature PA also reduced p and enhanced μ, but the effect was less pronounced compared to the Td = 125 °C sample (Fig. S3). To elucidate the origin of the improved electrical properties for TPA = 200 °C, we evaluated the detailed crystal structure using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Figure 4b–d indicate that hydrogen plasma treatment introduced defects into the surface region. As WP increased, the thickness of the surface defect layer also increased, which is consistent with the SIMS results in Fig. 3. Figure 4(e) shows that the surface defects decreased after PA. Therefore, we infer that the recovery of the crystal structure led to the improved electrical properties.

Figure 5 presents the electrical properties of undoped polycrystalline Ge, GeSn, and SiGe thin films (<150-nm thickness) grown on insulating substrates using various techniques. Typically, polycrystalline Ge layers exhibit p above 1017 cm−3, irrespective of the technique used, due to acceptor defects. The addition of small amounts of Sn in Ge slightly reduces p and improves μ. Increasing the Si composition in SiGe (>50%) significantly reduces p but leads to a substantial reduction in μ, attributable to an increase in carrier effective mass and grain boundary barriers. The polycrystalline Ge layers obtained in this study exhibit by far the lowest p in polycrystalline Ge-based thin films and maintain relatively high μ.

Discussion

We explored the impact of hydrogen plasma treatment on polycrystalline Ge layers by appropriately controlling the plasma treatment conditions. Hydrogen atoms were introduced into the polycrystalline Ge layer, as revealed by Raman measurements. Bonding between Ge and H occurred in the large-grain Ge layers, a phenomenon not observed in the small-grain Ge layers. Consistent with the bonding of Ge and H, the p of large-grain Ge layers dropped from 1017 cm−3 to the order of 1015 cm−3, marking the lowest reported value for p in a polycrystalline Ge layer. Following the nature of polycrystalline semiconductor thin films, μ decreased as p reduced, but low-temperature PA improved μ while further reducing p. These observations suggest that hydrogen atoms in Ge passivate not only acceptor defects but also grain boundary carrier traps. The resulting Ge layer simultaneously achieved high μ (170 cm2 V−1 s−1) and low p (4 × 1014 cm−3), an accomplishment unattainable with conventional polycrystalline group-IV semiconductor thin films. The findings of this study address the longstanding issue of acceptor defects hindering the application of polycrystalline Ge-based thin films in device applications, enabling a wide variety of advanced Ge-based devices.

Methods

Sample preparation

Ge precursors were deposited on SiO2 glass substrates using the Knudsen cell of a molecular beam deposition system (base pressure: 5 × 10−7 Pa). The Ge thickness was 100 nm and Ge deposition rate was fixed at 1.7 nm min−1. During deposition, the substrate was heated at Td of 50 or 125 °C45. Subsequently, the samples were loaded into a conventional tube furnace in a N2 (99.9%) atmosphere and annealed to induce solid-phase crystallization at 450 °C for 5 h. Hydrogen was introduced to the polycrystalline Ge layers using a plasma generator, Yamato PDC 210 (Fig. S2). To ensure safety, a mixed gas of Ar and H2 (Ar:H2 = 95:5) was used for the introduction of hydrogen69. The gas flow rate and pressure were fixed at 5 sccm and 10 Pa, respectively, while the WP ranged from 150 to 450 W. Following the plasma treatment, PA was conducted at a TPA of 100 – 400 °C for 4 h in a vacuum furnace (base pressure: 1 × 10−3 Pa).

Material characterization

Electron backscatter diffraction analyses were carried out using a Hitachi-high-tech SU7000 (voltage: 15 kV) equipped with an Oxford AZtec analysis attachment. Hall effect measurements were recorded using the Van der Pauw method with a Lake Shore M91-EV system, where both μ and p were averaged over five measurements for each sample. SIMS measurements were performed using a PHI ADEPT1010 instrument. Raman spectroscopy was conducted using a JASCO NRS-5100 (laser wavelength: 532 nm; spot size: 5 μm), and the laser power (0.5 mW) was kept sufficiently low to avoid influencing the crystal phase and peak shift. An FEI Tecnai Osiris instrument operating at 200 kV was used for TEM analysis. Cross-sections of the samples were prepared using a focused ion beam (Helios Nanolab 600i).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

References

Saraswat, K. et al. High Performance Germanium MOSFETs. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 135, 242–249 (2006).

Brunco, D. P. et al. Germanium MOSFET devices: advances in materials understanding, process development, and electrical performance. J. Electrochem. Soc. 155, H552 (2008).

Toriumi, A. & Nishimura, T. Germanium CMOS potential from material and process perspectives: be more positive about germanium. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 57, 010101 (2018).

King, R. R. et al. 40% efficient metamorphic GaInP/GaInAs/Ge multijunction solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 183516 (2007).

Shahrjerdi, D. et al. High-efficiency thin-film InGaP/InGaAs/Ge tandem solar cells enabled by controlled spalling technology. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 053901 (2012).

Michel, J., Liu, J. & Kimerling, L. C. High-performance Ge-on-Si photodetectors. Nat. Photonics 4, 527–534 (2010).

Matsue, M. et al. Strain-induced direct band gap shrinkage in local Ge-on-insulator structures fabricated by lateral liquid-phase epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 031106 (2014).

Kang, J., Takenaka, M. & Takagi, S. Novel ge waveguide platform on Ge-on-insulator wafer for mid-infrared photonic integrated circuits. Opt. Express 24, 11855 (2016).

Taniguchi, T. et al. Thermoelectric Si1−xGex and Ge Epitaxial Films on Si(001) with controlled composition and strain for group IV element-based thermoelectric generators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 141602 (2020).

Ozawa, T., Imajo, T., Suemasu, K. & Toko, K. High thermoelectric power factors in polycrystalline germanium thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 119, 132101 (2021).

Taraschi, G., Pitera, A. J. & Fitzgerald, E. A. Strained Si, SiGe, and Ge on-insulator: review of wafer bonding fabrication techniques. Solid State Electron 48, 1297–1305 (2004).

Yu, K. et al. Fabrication of high-hole-mobility germanium-on-insulator wafers through an easy method. J. Alloy. Compd. 750, 182–188 (2018).

Maeda, T. et al. Thin-Body Ge-on-Insulator p-Channel MOSFETs with Pt Germanide Metal Source/Drain. Thin Solid Films 508, 346–350 (2006).

Yang, H., Wang, D. & Nakashima, H. Evidence for existence of deep acceptor levels in SiGe-on-insulator substrate fabricated using Ge condensation technique. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 122103 (2009).

Feng, J. et al. Plummer, J.D. High-Performance Gate-All-Around GeOI p-MOSFETs Fabricated by Rapid Melt Growth Using Plasma Nitridation and ALD Al2O3 Gate Dielectric and Self-Aligned NiGe Contacts. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 29, 805–807 (2008).

Hu, S., Leu, P. W., Marshall, A. F. & McIntyre, P. C. Single-crystal germanium layers grown on silicon by nanowire seeding. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 649–653 (2009).

Toko, K., Ohta, Y., Tanaka, T., Sadoh, T. & Miyao, M. Chip-size formation of high-mobility Ge Strips on SiN films by cooling rate controlled rapid-melting growth. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 032103 (2011).

Hosoi, T., Suzuki, Y., Shimura, T. & Watanabe, H. Mobility characterization of Ge-on-insulator metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors with striped Ge channels fabricated by lateral liquid-phase Epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 173502 (2014).

Nakatsuka, O. et al. Mobility behavior of Ge1−xSnx layers grown on silicon-on-insulator substrates. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 49, 04DA10 (2010).

Toko, K., Nakao, I., Sadoh, T., Noguchi, T. & Miyao, M. Electrical properties of Poly-Ge on glass substrate grown by two-step solid-phase crystallization. Solid State Electron 53, 1159–1164 (2009).

Tsao, C.-Y., Huang, J., Hao, X., Campbell, P. & Green, M. A. Formation of heavily boron-doped hydrogenated polycrystalline germanium thin films by Co-sputtering for developing p+ emitters of bottom cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 95, 981–985 (2011).

Jung, H. W., Jung, W. S., Yu, H. Y. & Park, J. H. Electrical properties of phosphorus-doped polycrystalline germanium formed by solid-phase and metal-induced crystallization. J. Alloy. Compd. 561, 231–233 (2013).

Chou, C.-P., Lin, Y.-X., Hsieh, K.-Y. & Wu, Y.-H. Poly-GeSn Junctionless P-TFTs featuring a record high ION/IOFF ratio and hole mobility by defect engineering. J. Mater. Chem. 7, 5201–5208 (2019).

Yeh, W., Chen, H., Huang, H., Hsiao, C. & Jeng, J. Superlateral growth of a-Ge FILM BY EXCIMER LASER ANnealing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 094103 (2008).

Sakaike, K., Higashi, S., Murakami, H. & Miyazaki, S. Crystallization of amorphous Ge FILMS INDUCED BY SEMICONDUCTOR DIODE LASER ANNealing. Thin Solid Films 516, 3595–3600 (2008).

Li, Y.-S. et al. High-performance n-CHANNEL POLYCRYSTALLINE GERMANIUM THIN-FILM TRANSISTORS VIA CONTINUOUS-WAVE LASER CRYSTALLIZATION AND GREEN NANOSECOND LASER ANNEALING FOR SOURCE AND DRAIN DOPANT ACTIVation. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 58, SDDE02 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Poly-GeSn JUNCTIONLESS THIN-FILM TRANSISTORS ON INSULATORS FABRICATED AT LOW TEMPERATURES VIA PULSED LASER ANNealing. Phys. Status Solidi Rapid Res. Lett. 13, 1900420 (2019).

Takahashi, K. et al. Dopant behavior in heavily doped polycrystalline Ge1−xSnx layers prepared with pulsed laser annealing in water. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 57, 04FJ02 (2018).

Matsumura, R. & Fukata, N. Self-Organized <100> direction growth of germanium film on insulator obtained by high speed continuous wave laser annealing. Mater. Lett. 288, 129328 (2021).

Matsui, T., Kondo, M., Ogata, K., Ozawa, T. & Isomura, M. Influence of alloy composition on carrier transport and solar cell properties of hydrogenated microcrystalline silicon-germanium thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 142115 (2006).

Tada, M., Park, J.-H., Jain, J. R. & Saraswat, K. C. Low-temperature, low-pressure chemical vapor deposition and solid phase crystallization of silicon–germanium films. J. Electrochem. Soc. 156, D23 (2008).

Buzynin, Y. N. et al. High hole mobility of polycrystalline GeSn layers grown by hot-wire chemical vapor deposition on diamond substrates. Phys. Status Solidi Rapid Res. Lett. 16, 2100421 (2022).

Kamata, Y. et al. Operation of inverter and ring oscillator of ultrathin-body poly-Ge CMOS. Appl. Phys. Express 7, 121302 (2014).

Usuda, K. et al. High-performance Poly-Ge short-channel metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors formed on SiO2 layer by flash lamp annealing. Appl. Phys. Express 7, 056501 (2014).

Uchida, N. et al. Locquet, J.-P. Carrier and heat transport properties of poly-crystalline GeSn films for thin-film transistor applications. J. Appl. Phys. 126, 145105 (2019).

Sato, T., Hanafusa, H. & Higashi, S. Investigation on electrical characteristics of TFTs fabricated with germanium films crystallized by atmospheric-pressure micro thermal plasma jet irradiation. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 61, SC1011 (2022).

Asadirad, M. et al. High-performance flexible thin-film transistors based on single-crystal-like germanium on glass. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2, 1600041 (2016).

Park, J.-H., Kasahara, K., Hamaya, K., Miyao, M. & Sadoh, T. High carrier mobility in orientation-controlled large-grain (≥50 μm) Ge directly formed on flexible plastic by nucleation-controlled gold-induced-crystallization. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 252110 (2014).

Wang, Z., Jeurgens, L. P. H., Sigle, W. & Mittemeijer, E. J. Observation and origin of extraordinary atomic mobility at metal-semiconductor interfaces at low temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 016102 (2015).

Kasahara, K. et al. Electrical properties of pseudo-single-crystalline germanium thin-film-transistors fabricated on glass substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 142102 (2015).

Higashi, H. et al. A crystalline germanium flexible thin-film transistor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 222105 (2017).

Suzuki, T., Joseph, B. M., Fukai, M., Kamiko, M. & Kyuno, K. Low-Temperature (330 °C) Crystallization and Dopant Activation of Ge Thin Films via AgSb-Induced Layer Exchange: Operation of an n-Channel Polycrystalline Ge Thin-Film Transistor. Appl. Phys. Express 10, 095502 (2017).

Toko, K. & Suemasu, T. Metal-induced layer exchange of group IVmaterials. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 53, 373002 (2020).

Sadoh, T., Kai, Y., Matsumura, R., Moto, K. & Miyao, M. High carrier mobility of Sn-doped polycrystalline-Ge films on insulators by thickness-dependent low-temperature solid-phase crystallization. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 232106 (2016).

Toko, K., Yoshimine, R., Moto, K. & Suemasu, T. High-hole mobility polycrystalline Ge on an insulator formed by controlling precursor atomic density for solid-phase crystallization. Sci. Rep. 7, 16981 (2017).

Nozawa, K., Nishida, T., Ishiyama, T., Suemasu, T. & Toko, K. n-type polycrystalline germanium layers formed by impurity-doped solid-phase growth. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 5, 1444–1450 (2023).

Imajo, T. et al. Record-high hole mobility germanium on flexible plastic with controlled interfacial reaction. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 4, 269–275 (2022).

Nozawa, K. et al. High-electron mobility P-doped polycrystalline GeSn layers formed on insulators at low temperatures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 201901 (2023).

Haesslein, H., Sielemann, R. & Zistl, C. Vacancies and self-interstitials in germanium observed by perturbed angular correlation spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 2626–2629 (1998).

Imajo, T., Ishiyama, T., Nozawa, K., Suemasu, T. & Toko, K. Acceptor defects in polycrystalline ge layers evaluated using linear regression analysis. Sci. Rep. 12, 14941 (2022).

Moto, K. et al. Polycrystalline thin-film transistors fabricated on high-mobility solid-phase-crystallized Ge on Glass. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 212107 (2019).

Moto, K. et al. Sn concentration effects on polycrystalline GeSn thin film transistors. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 42, 1735–1738 (2021).

Yoshikawa, I. et al. Low-temperature crystallization of Ge-Rich GeSn layers on Si3N4 substrate. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 70, 151–155 (2017).

Moto, K., Yoshimine, R., Suemasu, T. & Toko, K. Improving carrier mobility of polycrystalline Ge by Sn Doping. Sci. Rep. 8, 14832 (2018).

Xu, C., Gong, X., Miyao, M. & Sadoh, T. Enhanced Mobility of Sn-Doped Ge thin-films (≤50 nm) on insulator for fully depleted transistors by nucleation-controlled solid-phase crystallization. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 042101 (2019).

Mizoguchi, T. et al. Solid-phase crystallization of GeSn thin films on GeO2-Coated Glass. Phys. Status Solidi Rapid Res. Lett. 16, 2100509 (2022).

Maeda, S. et al. Interfacial nucleation control in amorphous GeSn thin films using bilayer structure. Cryst. Growth Des. 23, 5535–5540 (2023).

Aya, Y., Takeda, K., Wakisaka, K. & Nishio, K. Electrical properties of polycrystalline Si1−xGex thin-films prepared by a solid-phase crystallization method. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 42, L1308–L1311 (2003).

Mizoguchi, T. et al. Composition dependent properties of p- and n-type polycrystalline group-IV alloy thin films. J. Alloy. Compd. 887, 161306 (2021).

Kamins, T. I. & Marcoux, P. J. Hydrogenation of transistors fabricated in polycrystalline-silicon films. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 1, 159–161 (1980).

Honda, S. et al. Effect of hydrogen passivation on polycrystalline silicon thin films. Thin Solid Films 487, 152–156 (2005).

Funase, Y., Suzuno, M., Toko, K. & Suemasu, T. Effect of atomic-hydrogen irradiation on reduction of residual carrier concentration in β-FeSi2 films grown on si substrates by atomic-hydrogen-assisted molecular beam epitaxy. J. Cryst. Growth 378, 365–367 (2013).

Nayfeh, A., Chui, C. O., Saraswat, K. C. & Yonehara, T. Effects of hydrogen annealing on heteroepitaxial-Ge Layers on Si: surface roughness and electrical quality. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 2815–2817 (2004).

Hanya, Y. et al. Effects of hydrogen on structure and crystallization behavior of sputter-deposited amorphous germanium films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 59, 075506 (2020).

Weber, J. R., Janotti, A., Rinke, P. & Van De Walle, C. G. Dangling-bond defects and hydrogen passivation in germanium. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 142101 (2007).

Seto, J. W. Y. The electrical properties of polycrystalline silicon films. J. Appl. Phys. 46, 5247–5254 (1975).

Rivillon, S., Chabal, Y. J., Amy, F. & Kahn, A. Hydrogen passivation of germanium (100) surface using wet chemical preparation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 253101 (2005).

Kitajima, M. et al. Hydrogen molecules in crystalline silicon. Mater. Sci. Forum 258–263, 203–210 (1997).

Hu, Q., Zhang, X. & Hao, H. Inter. A review of hydrogen-air cloud explosion: the fundamentals, overpressure prediction methods, and influencing factors. J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 13705–13730 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by NEDO (No. P14004) and JST FOREST (No. JPMJFR222J), JSPS KAKENHI (No. 24KJ0509), TEPCO Memorial Foundation, the JACI Prize for Encouraging Young Researchers, and Sasakawa foundation. The authors are grateful to Prof. T. Sekiguchi (University of Tsukuba) and Prof. N. Fukata (NIMS) for helpful discussions and experimental support. Some experiments were conducted at the Advanced Research Infrastructure for Materials and Nanotechnology in Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K. N. and K. T. conceived and designed the study. K. N. and T. M. fabricated the sample. K. N., K. I., T. M., N. S., and N. Y. performed analyses. K. T. and T. S. managed and supervised the study. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nozawa, K., Igura, K., Mizoguchi, T. et al. Hydrogen passivation effects on polycrystalline germanium thin films. NPG Asia Mater 17, 26 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-025-00611-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-025-00611-w