Abstract

Flexible electronics have significantly influenced modern daily life, particularly in personalized, human-centric applications, due to their ability to conform to curved surfaces. Building on this adaptability, researchers are now focusing on developing stretchable electronic devices that promise next-generation form factors, offering unprecedented user experience and functionalities. Current approaches employ rigid electronic materials configured in strain-accommodating geometries, achieving a high level of technological maturity by leveraging well-established technologies. However, these strategies face limitations, particularly in terms of long-term durability under repeated deformation, primarily due to their reliance on non-stretchable components. To overcome these limitations and facilitate durable deformation, intrinsically stretchable electronic materials have emerged as a promising solution. This review highlights recent advancements in intrinsically soft electronics, with a particular focus on stretchable conductors based on metallic components. Key elements of intrinsically stretchable conductors are discussed, including elastomers used as stretchable substrates, and metallic ingredients such as low-dimensional metallic nanomaterials and liquid metals. Additionally, we explore various assembly and patterning techniques for these materials. Practical applications of metal-based intrinsically soft conductors are highlighted, and this review concludes with an outlook on the prospects and potential challenges for these emerging technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent advancements in electronics have propelled modern human civilization forward in transformative ways. Innovations in materials science and semiconductor processing have enabled the creation of electronic devices that are not only smaller in size but also vastly superior in performance. For example, the computational power of modern mobile phones far exceeds that of the Apollo 11 mission’s onboard computer, while being remarkably compact1. These advancements have paved the way for the development of wearable and implantable electronics, technologies that seamlessly integrate with the human body. Applications of these devices span from medical and biological monitoring to sports, entertainment, and industrial operations, enhancing both functionality and efficiency.

Traditional electronic materials, such as metals and silicon, have been instrumental in these achievements due to their excellent electrical properties and ease of processing2,3. Moreover, processing those materials in ultrathin, sub-micrometer scale and patterning them with the structures, which absorb mechanical stress, enabled flexibility and even stretchability4,5,6,7. However, this methodology is constrained by limited deformation capabilities and susceptibility to mechanical fatigue during repeated use8,9.

To overcome these challenges, recent research has shifted toward developing intrinsically soft and stretchable materials8,10. These materials not only withstand extensive deformation but also retain their performance under repeated mechanical stresses11,12. For instance, hydrogels, liquid metals (LMs), and polymer composites with conductive fillers have emerged as promising candidates due to their unique combination of softness, stretchability, and excellent electrical properties13. Such materials are particularly valuable in biomedical and industrial applications, where flexibility and biocompatibility are critical14.

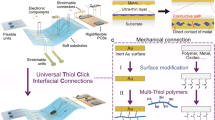

This study reviews the latest research trends and future directions for intrinsically soft electronic materials, with a focus on metal-based systems (Fig. 1). It first examines structural engineering strategies for imparting stretchability to traditional rigid materials, analyzing their advantages and limitations. Next, it introduces cutting-edge intrinsically soft metallic materials, detailing their properties and how they overcome the constraints of rigid counterparts. The discussion then shifts to fabrication techniques and structural designs that enhance the performance and durability of these materials. Finally, the study highlights applications of these materials in electronic components such as circuits, displays, energy storage devices, and computing systems, illustrating their potential to revolutionize the field of flexible electronics.

Reproduced with permission107. Copyright 2021, AAAS.

Complications of conventional flexible electronics

The development of flexible electronics has revolutionized applications in wearable devices, medical implants, and soft robotics. However, conventional approaches encounter critical limitations, particularly under highly deformable or stretchable conditions. The primary strategy has relied on ultrathin materials capable of conforming to non-planar surfaces while preserving functionality. Despite their potential, these methods are hindered by the intrinsic rigidity of the materials and the intricate mechanical and electrical design processes needed to maintain performance under strain. This chapter delves into these challenges, analyzing the strategies employed and their associated limitations.

Strategies for flexible electronics

Flexible electronics have primarily achieved mechanical compliance by employing ultrathin materials, enabling devices to conform to curved or dynamic surfaces without significantly compromising electrical properties15. Thin metal films, often deposited and patterned on flexible substrates like polyimide (PI) or parylene, exemplify this approach. The primary advantage of ultrathin materials is their ability to reduce bending stiffness, allowing for substantial flexibility even when rigid materials are utilized. However, while effective for addressing flexibility in bending, this strategy falls short when dealing with complex deformations such as stretching or twisting, key requirements for next-generation applications like epidermal electronics and biomedical implants.

Structural designs for stretchable electronics using ultrathin materials

To address the limitations of ultrathin materials, various structural designs have been employed to enhance the stretchability of flexible electronics. These designs enable rigid materials to withstand greater mechanical strain without compromising their electrical performance. Four major approaches are commonly used:

In-plane serpentine structure

In-plane serpentine structures utilize wavy or serpentine patterns for conductive traces, enabling stretchability by allowing the material to unfold under tensile stress. This geometric configuration accommodates mechanical deformation while the conductive material itself remains rigid, thus enhancing flexibility (Fig. 2a)16. However, a key limitation of this approach is the significant space required for serpentine patterns, which reduces the effective functional density of the device.

a, b In-plane serpentine structure for stretchability. Reproduced with permission16. Copyright 2013, RSC Publishing. Reproduced with permission17. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature. c, d Out-of-plane buckling structure for stretchability. Reproduced with permission18. Copyright 2006, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission19. Copyright 2015, AAAS. e, f Helical structure for stretchability. Reproduced with permission14. Copyright 2020, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission21. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature. g, h Origami and kirigami structure for stretchability. Reproduced with permission22. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission23. Copyright 2018, John Wiley & Sons. i–l Complications of the stretchable designs; complicated design and manufacturing processes, low device resolution, and mechanical stress. Reproduced with permission24. Copyright 2014, National Academy of Science. Reproduced with permission25. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. Reproduced with permission26. Copyright 2020, Elsevier.

For instance, Jiao et al. developed a vertical serpentine structure to achieve flexibility and stretchability using intrinsically rigid materials17. This structure was fabricated on a silicon-based platform, where functional nodes were interconnected through serpentine designs to provide mechanical compliance. The process involved photolithography and etching on a silicon wafer to create the base for the serpentine interconnects, which were subsequently encapsulated in multiple layers of Parylene-C. This encapsulation protected the conductive layers while allowing the structure to stretch and bend without compromising electrical performance. The resulting vertical serpentine conductor exhibited exceptional mechanical properties, withstanding up to 350% strain while maintaining electrical stability. Experimental results indicated less than a 2% change in electrical resistance under 300% strain (Fig. 2b), and the structure endured over 100 stretching cycles at 100% strain without significant degradation, demonstrating its durability.

Out-of-plane buckling structure

Out-of-plane buckling structures enable stretchability by leveraging vertical deformations. When a thin, rigid film is bonded to a pre-stretched elastomer and subsequently released, the film forms out-of-plane wrinkles or buckles (Fig. 2c)18. This configuration accommodates strain without stretching the material itself, effectively maintaining conductivity during deformation. However, controlling the uniformity and direction of buckling patterns remains challenging.

For example, Xu et al. employed this technique by bonding silicon microstructures onto a pre-stretched elastomer substrate19. Upon releasing the pre-strain, the silicon structures buckled into three-dimensional (3D) geometries, enabling mechanical strain accommodation without fracturing (Fig. 2d). The structures maintained electrical continuity and mechanical stability under cyclic strains of up to 100% over 1,000 cycles, demonstrating their durability for stretchable electronics.

Coiled structure and helical structure

The coiled and/or helical structure, often applied to wires and fibers, involves creating a spring-like configuration that extends and compresses under strain. This configuration offers significant stretchability while maintaining electrical continuity (Fig. 2e)20. The downside of this design as electronic materials is that it introduces inductance and resistance variations under different strain conditions, which can lead to signal distortion in high-frequency applications (Fig. 2f)21.

Origami and Kirigami design

Origami and kirigami techniques utilize folding and cutting patterns in thin films to enable stretchability, accommodating significant mechanical deformation without damaging the material (Fig. 2g)22. These designs are particularly effective for applications requiring large strains, though they can reduce functional density and complicate fabrication processes.

For example, Guan et al. implemented a kirigami-inspired design to transform non-stretchable polymer conducting nanosheets (NSs) into highly stretchable materials23. By introducing precise cuts into a polymer sheet containing Poly(3-butylthiophene-2,5-diyl) conductive nanowires (NWs) embedded in a robust polymer matrix, the structure achieved up to 2000% strain by deforming along the cut lines. The NSs retained stable electrical performance over 1000 cycles of 2000% strain, with conductivity improving to 4.002 S/cm after iodine doping, compared to the original 2.2 × 10⁻³ S/cm (Fig. 2h).

Drawbacks of structural design strategies

While structural design strategies offer innovative ways to impart stretchability to rigid materials, these approaches are fundamentally limited by the intrinsic rigidity of the materials themselves. Metals, semiconductors, and other stiff components encounter significant challenges under repetitive mechanical strain, constraining their long-term reliability and applicability in soft electronic devices.

One major limitation is the complexity of adapting rigid materials for stretchable applications. Geometric designs often require intricate patterns and thin-film architectures, necessitating advanced fabrication techniques that involve multiple deposition, patterning steps, and even transfer24. These processes are not only technically demanding but also time-intensive and costly, adding significant barriers to scalability and widespread adoption (Fig. 2i, j).

Another drawback arises from the need for 3D deformation in inherently 2D materials. Accommodating such deformations requires the inclusion of marginal spaces in the design, leading to increased size and reduced functional density (Fig. 2k)25. For instance, serpentine structures used in stretchable displays demand additional spacing, which decreases pixel density, diminishing image resolution and overall device performance. This trade-off between stretchability and functional density remains a critical challenge for applications requiring high precision and compact designs.

Moreover, reducing the thickness of rigid materials to enhance flexibility compromises their mechanical robustness (Fig. 2l)26. Under repetitive mechanical strain, such as cyclic stretching or bending, stress accumulates within the material, eventually leading to fatigue, micro-cracking, or delamination at interfaces. These issues degrade performance and shorten the device’s operational lifespan. Even in commercially available flexible electronics, hinge regions often experience accelerated mechanical degradation due to repeated stress.

Despite advancements in structural design, these limitations underscore the necessity of alternative approaches. Intrinsically soft materials offer a promising solution by eliminating the reliance on geometric adaptations to achieve stretchability. By addressing the fundamental challenges posed by rigid materials, intrinsically soft electronics can enable devices that are not only stretchable but also robust, functional, and reliable over extended periods.

Intrinsically stretchable substrate/encapsulation materials

As electronics evolve towards wearable, implantable, and soft robotic applications, the demand for highly stretchable and deformable materials, particularly those suitable for use as substrates and encapsulation layers, has become increasingly critical27. Conventional electronics rely on rigid or semi-rigid substrates, which significantly limit their performance in environments requiring high flexibility and adaptability. In contrast, intrinsically soft materials offer an innovative solution by combining high elasticity with mechanical compliance, enabling electronic devices to withstand stretching, twisting, and bending without compromising functionality.

Soft electronics typically involve conductive components, which serve as circuits, and insulating materials, which function as substrates or encapsulation layers. To achieve truly intrinsically soft electronics, both conductive and insulating materials must exhibit comparable softness. This chapter delves into a range of intrinsically soft insulating materials, including flexible polymers, elastomers, and hydrogels, that are widely utilized as substrates or encapsulation layers in soft electronics, highlighting their properties and applications.

Flexible polymers

Flexible polymers, such as polyimide and parylene, have long been considered for use in flexible electronics due to their mechanical flexibility and ease of processing. While not inherently stretchable, these polymers can serve as flexible substrates for thin-film electronics or in combination with more elastic materials.

Parylene

Parylene is a widely utilized material in flexible electronics, valued for its exceptional dielectric properties and chemical resistance. Its vapor-phase deposition process enables the formation of conformal, pinhole-free coatings, making it ideal for applications requiring electrical insulation and protection from environmental factors like moisture and chemicals28. Parylene’s inherent flexibility further enhances its suitability for scenarios where devices must endure mechanical deformation.

For example, Werkmeister and Nickel investigated the use of Parylene-N and Parylene-C as substrates and gate dielectrics in organic thin-film transistors29. The chemically vapor-deposited Parylene-N film demonstrated an impressively low surface roughness of approximately 4 nm. Utilizing the lift-off technique, a gold layer and a pentacene layer were deposited onto the parylene substrate to construct the electronic components. The resulting organic thin-film transistor exhibited remarkable mechanical flexibility, maintaining consistent performance even under deformation with a bending radius as small as 1 mm (Fig. 3a). This highlights Parylene’s potential in advanced flexible electronic applications.

a–d Flexible polymers. Reproduced with permission29. Copyright 2013, RSC Publishing. Reproduced with permission31. Copyright 2013, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission34. Copyright 2020, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission23. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. e, f Physically (e) and chemically (f) crosslinked elastomers. Reproduced with permission37. Copyright 2021, John Wiley & Sons. g, h Thermoplastics. Reproduced with permission43. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission44. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature. i, j Block-copolymers. Reproduced with permission46. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission45. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature. k, l Silicones. Reproduced with permission54. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission44. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature. m, n Photocrosslinkable elastomers. Reproduced with permission57. Copyright 2020, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission58. Copyright 2021, AAAS. o–q Intrinsically soft hydrogel substrate. Reproduced with permission62. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission63. Copyright 2019, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission64. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature.

Polyimide (PI)

PI is a high-performance polymer renowned for its excellent thermal stability (–296 to 400 °C), mechanical robustness, and flexibility30. These properties make PI a preferred choice for applications such as flexible printed circuit boards (FPCBs), where it serves as a reliable substrate for thin metal interconnects. Its outstanding thermal resistance ensures durability in high-temperature environments, while its mechanical flexibility makes it ideal for wearable electronics requiring minimal bending stiffness.

For example, Jin et al. developed flexible surface acoustic wave resonators using vertically-aligned zinc oxide (ZnO) nanocrystals deposited on PI film. The ZnO nanocrystal film, with a thickness of 1.7–4 μm, was sputtered onto a 100 μm-thick PI substrate31. The resulting resonator exhibited remarkable flexibility, maintaining its functionality even when wrapped around a finger. This demonstrates polyimide’s potential for use in flexible electronics, sensors, and lab-on-a-chip devices, highlighting its capability to endure substantial mechanical deformation while preserving performance (Fig. 3b).

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET)

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is widely used in flexible electronics due to its transparency, mechanical strength, and cost-effectiveness32,33. Its optical clarity and flexibility make it a popular choice for applications like flexible displays and touchscreens. However, PET’s low stretchability and limited thermal and chemical stability restrict its use in environments requiring significant elongation or harsh conditions. For instance, Li et al. fabricated large-scale, transparent molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂)-based transistors and logic circuits on PET substrates (Fig. 3c) by transferring a wafer-scale MoS₂ monolayer onto indium tin oxide (ITO) and aluminum oxide (Al2O3)-treated PET34. The resulting devices demonstrated durability, maintaining functionality after 1,000 bending cycles at 2% strain.

Other flexible polymers

In addition to parylene, polyimide, and PET, polymers such as polycarbonate (PC)35 and polyether ether ketone (PEEK)36 have been explored for flexible electronics due to their balance of flexibility, strength, and durability. These materials are suitable for applications in flexible circuits, displays, and biomedical devices. For instance, Quereda et al. fabricated a tungsten disulfide (WS₂) photodetector on a transparent polycarbonate film through a simple direct rubbing technique with WS₂ micropowder (Fig. 3d)37. The polycarbonate substrate, chosen for its abrasion resistance, supported the fabrication process without degradation. The photodetector demonstrated a responsivity of 114 mA/W and a fast response time of ~70 μs, with stable performance under 0.7% uniaxial elongation.

Elastomeric materials

Elastomers are a class of polymers that are intrinsically stretchable, offering both high elasticity and mechanical compliance. These materials can undergo large strains (up to several hundred percent) without permanent deformation, making them ideal for applications in soft electronics where significant mechanical deformation is required. Elastomers can be broadly classified into physically crosslinked elastomers and chemically crosslinked elastomers, each with a crosslinking mechanism, distinct properties, and fabrication processes.

Physically crosslinked elastomers

Physically crosslinked elastomers rely on physical inter-chain interactions, such as hydrogen bonding and electrostatic forces, to maintain their structure38,39. These materials typically consist of soft segments, which provide stretchability by unfolding under mechanical deformation, and hard segments, which ensure structural integrity through inter-chain interactions (Fig. 3e). The ratio of soft to hard segments dictates the material’s overall softness and stretchability. Compared to chemically crosslinked elastomers, physically crosslinked variants exhibit greater plasticity and stretchability due to their lower crosslinking density and reversible bonding mechanisms. Additionally, their capacity to accommodate nanofillers makes them well-suited as nanocomposite matrices. However, their weak resistance to heat and chemicals limits their durability in harsh environments.

Polyurethane (PU)

Polyurethane (PU) is a physically crosslinked elastomer valued for its high elasticity and toughness, making it a popular material in wearable electronics, sensors, and soft robotics. Its ability to endure high strain without mechanical failure makes it particularly suitable for harsh environments40,41. However, PU’s sensitivity to moisture and humidity can affect its long-term mechanical properties. Despite this limitation, PU remains a versatile and easily tunable material for soft electronics due to its mechanical robustness and ease of processing42.

For example, Cao et al. developed stretchable electrodes with anti-friction properties by forming hydrogen bonds between hydrophilic PU and wet gold grains, achieving a robust interfacial binding strength of 1,243.4 N/m—significantly higher than polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) or styrene-ethylene-butylene-styrene (SEBS) substrates (Fig. 3g)43. The Au/PU device demonstrated excellent electrical conductivity (<500 Ω/□) even after 1100 friction cycles at 130 kPa and maintained low electrical resistance (1.09 × 10⁻³ Ω·m) under 400% strain. This versatile electrode was successfully used as a bioelectrode and an anti-friction pressure sensor array.

Lv et al. introduced a sustainable PU-based printed conductor using vegetable oil-derived polyols crosslinked through carbamate-oxime and hydrogen bonds44. This PU/Ag composite exhibited a conductivity of 12,833 S/cm, stretchability of 350%, and low hysteresis (0.333) after 100% cyclic stretching (Fig. 3h). As a proof of concept, the composite was implemented in a soft smart gripper for fruit maturity sensing, detecting ripeness via impedance spectroscopy and transmitting signals to a pneumatic actuator for automated gripping. Additionally, the composite was recyclable, allowing separation into reusable PU and Ag flakes through solvent dissolution and centrifugation.

Block-copolymers

Block copolymers, such as styrene-butadiene-styrene (SBS) and SEBS, are widely used as physically crosslinked elastomers due to their combination of mechanical strength and stretchability45. These materials consist of alternating hard and soft segments, where the hard blocks provide reinforcement, and the soft blocks contribute to elasticity, making them ideal for flexible conductive composites and stretchable electrodes.

For example, Koo et al. developed intrinsically soft transistors by integrating semiconducting carbon nanotubes (CNTs), microcracked gold nanomembranes, and a chemically vapor-deposited elastic polymer dielectric on a SEBS substrate (Fig. 3i)46. The dielectric material, designed with soft (isononyl acrylate) and hard (trimethyl-trivinyl cyclotrisiloxane) segments, maintained stretchability while ensuring high uniformity and stable electrical performance. The transistor array, comprising 1000 devices on a wafer, demonstrated functionality under 40% strain for over 1000 cycles and supported logic operations such as NAND, NOR, and XOR gates.

In another study, Li et al. incorporated a soft SEBS interlayer with a Young’s modulus of 2.83 MPa to create tissue-level modulus devices, including transistors and sensors (Fig. 3j)45. The SEBS layer, combined with polyacrylamide (PAAm) hydrogel, exhibited significantly reduced stiffness compared to SEBS-PDMS composites. A stretchable polymer semiconductor and CNTs network were deposited onto the SEBS-PAAm substrate, resulting in a soft transistor with an on/off ratio of 10⁴ and stable charge-carrier mobility (~0.7 cm²/Vs) after 1000 cycles at 100% strain. The device’s tissue-like softness enabled conformal skin contact without delamination during mechanical deformation.

Chemically crosslinked elastomers

Chemically crosslinked elastomers are characterized by irreversible inter-chain interactions formed through covalent bonds. These crosslinks are typically initiated by external triggers, such as crosslinking agents or UV radiation, depending on the mechanism employed (Fig. 3f)38,47. The strong covalent bonds provide exceptional resistance to chemical, mechanical, and thermal stimuli, making these elastomers highly durable. However, the dense crosslinking limits nanofiller incorporation and reduces plasticity, often resulting in a higher modulus compared to their physically crosslinked counterparts48.

Silicone (PDMS, Ecoflex)

Silicone elastomers, particularly PDMS and Ecoflex, are widely utilized in soft electronics due to their softness, with Young’s modulus values of 43.3 kPa for Ecoflex and 353 kPa for PDMS—comparable to that of human skin (25–260 kPa)49. PDMS is prized for its biocompatibility, optical transparency, and chemical inertness, making it a versatile material for substrates, encapsulation layers, and dielectric applications50,51. Its elasticity enables stretching up to several hundred percent without permanent deformation52. Ecoflex, being softer, is often used in applications requiring extreme deformability, such as soft robotics and wearable sensors.

A key strength of silicone elastomers is their processability; PDMS can be molded into complex shapes via soft lithography, ideal for microfluidics, flexible circuits, and stretchable sensors. However, limitations like poor adhesion and high gas permeability (55 μm for CO₂ and He)53 necessitate surface modifications or composite designs to enhance performance.

For instance, Lu et al. developed a laser-induced graphene (LIG)-PDMS composite, increasing the stretchability of brittle LIG from 20% to 220% using an adhesive hydrogel transfer process (Fig. 3k)54. The LIG-hydrogel electrode on PDMS demonstrated high biocompatibility and antibacterial properties, serving as wearable sensors for mechanical, humidity, and electrocardiography (ECG) monitoring. Its softness enabled its application as an implantable epicardial monitor on rodent hearts. Similarly, Lee et al. created a printable conductive elastomer composite combining Ag particles, multi-walled CNTs, and PDMS, achieving high stretchability (150%) and conductivity (6682 S/cm)55. Printed into freestanding 3D structures with 100 μm resolution (Fig. 3l), the composite functioned as on-skin electrodes for temperature sensing and feedback displays, maintaining performance under 40% strain.

Photocrosslinkable elastomers

Photocrosslinkable elastomers represent a promising class of materials for soft electronics, offering precise control over mechanical properties and geometry through UV-induced chemical crosslinking. These materials are particularly suited for applications requiring high-resolution patterning, such as microelectronics and microfluidic devices, due to their tunable stiffness, elasticity, and stretchability. A commonly used example, pure polyurethane acrylate (PUA), exhibits a Young’s modulus of 1.4 MPa56. Fabrication involves spin-coating or printing liquid precursors onto substrates, followed by UV curing, enabling intricate, flexible patterns. While promising, further research is necessary to optimize their mechanical and electrical performance for practical applications.

For instance, Liu et al. developed a fully stretchable organic light-emitting electrochemical cell array and thin-film transistor using a PUA-AgNWs electrode, poly(3 4-ethylenedioxythiophene):polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) hole injection layer, and diamethacrylate-modified perfluoropolyether dielectric57. The UV-crosslinked dielectric layer demonstrated resistance to mechanical deformation and chemical exposure, with a high breakdown voltage of over 100 V at a thickness below 200 nm, highlighting its potential for stretchable organic thin-film transistors (Fig. 3m). The integrated device achieved 30% stretchability without delamination or cracking and exhibited a turn-on current density of ~2 mA/cm².

In another study, Li et al. introduced photopatternable liquid crystal elastomer (LCE) actuators using digital light processing58. During fabrication, shear printing aligned the liquid crystal in the resin tray, followed by photocrosslinking with projected UV light (Fig. 3n). The resulting LCE exhibited thermal actuation properties, reconfiguring its crosslinking network in response to heat. This enabled behaviors such as locomotion and weight lifting, showcasing its potential for optoelectric sensing and actuation in soft robotics.

Hydrogels

Hydrogels are water-swollen polymers with tunable mechanical properties and high biocompatibility, making them ideal for elastic electronics59,60. Their tissue-like softness and conformability enable seamless integration with biological tissues, making them valuable for wearable devices, bioelectronics, and implantable sensors. Hydrogels serve as substrates, dielectric layers, or encapsulation materials, offering flexibility and adaptability to various shapes61.

One advantage of hydrogels is their adjustable mechanical properties, controlled by crosslinking density, polymer composition, or water content. This tunability ensures compatibility with biological tissues, minimizing mechanical mismatch in bioelectronic applications. Hydrogels’ swelling behavior can also enable self-healing or adaptive responses to environmental changes like humidity or temperature. Commonly used hydrogels include polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) for mechanical strength and encapsulation, PAAm for high elasticity, and polyethylene glycol for biocompatibility and resistance to protein adsorption. Advanced hydrogels, such as those with nanofillers or double-network structures, offer enhanced toughness and stability.

Despite their benefits, hydrogels face challenges, including susceptibility to drying and residual ionic conductivity, which can cause signal leakage or noise in dielectric applications. Strategies like composite designs or hydrophobic coatings mitigate these issues, extending hydrogel functionality in practical devices.

For instance, Ohm et al. developed a conductive hydrogel composite with a soft modulus of 10 kPa and conductivity of 374 S/cm using 5 vol.% Ag flakes forming a percolation network in a PAAm-alginate matrix62. The composite exhibited stable electrical performance under 250% strain and minimal resistance change over 100 stretching cycles, making it suitable for neural electrodes and actuators. Integrated with a shape-memory alloy, the hydrogel powered a swimming robot with a speed of 40 mm/s (Fig. 3o).

Liu et al. created a conductive hydrogel for neuromodulation by removing ionic liquid from an ionic liquid-PEDOT:PSS hydrogel63. The resulting material achieved a conductivity of 47.4 S/cm, stretchability of 20%, and a Young’s modulus of 32 kPa. It maintained stable impedance under deformation and withstood 10,000 stretching cycles with minimal resistance changes. Using photolithography, the hydrogel was patterned with 100 μm resolution and exhibited high charge storage capacity (164 mC/cm²), making it effective for low-voltage sciatic nerve stimulation in rodents (Fig. 3p).

Huang et al. enhanced hydrogel mechanics for soft electronics by developing a double-network polyacrylamide-calcium alginate hydrogel64. This design enabled 400% strain without damage due to its interconnected porous structure. Replacing water with glycerol increased the Young’s modulus from 77.5 to 252 kPa, improving stability in low-humidity conditions. The organohydrogel retained over 80% of its weight after 36 hours, proving its suitability for wearable sensors in variable environments (Fig. 3q).

Conductive metallic nanomaterials for intrinsically soft nanocomposites

The advancement of intrinsically soft electronics relies on the development of materials that combine high electrical conductivity with exceptional deformability. Metallic nanomaterials, including zero-dimensional (0D) nanoparticles (NPs), one-dimensional (1D) NWs, and two-dimensional (2D) NSs, play a pivotal role in creating conductive and stretchable composites. By embedding these nanomaterials into elastomeric or other soft matrices, conductive networks are formed that preserve electrical performance under mechanical deformation. This chapter explores the unique properties, advantages, and fabrication techniques of metallic nanomaterials, focusing on their integration into soft electronics65. Additionally, methods to functionalize and enhance these nanocomposites for improved performance, such as electric conductivity, stretchability, and biocompatibility, are discussed, emphasizing their potential in next-generation electronic applications. The summary discussing characteristics of the metallic nanomaterials and LMs are presented in Table 1.

Percolation network theory and nanocomposites

Understanding the role of metallic nanomaterials in soft electronics begins with the concept of a percolation network. Percolation theory explains how conductive fillers, dispersed within an insulating matrix (such as an elastomer), form continuous pathways for electrical conduction once their concentration surpasses a critical threshold—the percolation threshold66,67. Below this threshold, the material remains non-conductive, but exceeding it establishes a conductive network, enabling current flow (Fig. 4a, b)68,69.

a, b Percolation network theory and percolation thresholds. Reproduced with permission69. Copyright 2024, MDPI. c–f 0D metallic nanoparticles. Reproduced with permission75. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission77. Copyright 2018, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission79. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. g–j Quantum dots. Reproduced with permission81. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission82. Copyright 2020, Springer Nature. k–n 1D metallic nanowires. Reproduced with permission87. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. Reproduced with permission91. Copyright 2017, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission94. Copyright 2014, Springer Nature. o–r 2D metallic nanosheets. Reproduced with permission98. Copyright 2021, AAAS. Reproduced with permission100. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission101. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society.

In metallic nanocomposites, achieving an effective percolation network with minimal filler content is crucial. The geometry70, size, and distribution of metallic fillers significantly influence the percolation threshold and composite conductivity71. Furthermore, these factors impact the mechanical properties of the composite, including stretchability and durability, by governing the interactions between the fillers and the matrix. Careful optimization of these parameters facilitates the development of soft, conductive nanocomposites suitable for diverse applications, such as sensors, circuits, and energy storage devices72.

Metallic nanofillers

Metallic nanofillers are the core components used to create percolation networks in soft, conductive composites. These fillers can be classified into three main categories based on their dimensionality: 0D NPs, 1D NWs, and 2D NSs. Each of these forms of nanomaterials offers unique properties that can be leveraged to optimize the performance of soft electronics.

0D metallic nanoparticles (NPs)

Metallic NPs are 0D nanomaterials with small aspect ratios, characterized by their ability to infiltrate polymeric matrices or fill gaps between other nanomaterials without compromising functionality (Fig. 4c)73. However, their small size and low aspect ratio make it challenging for NPs alone to form effective percolation networks74. Consequently, nanoparticles are often used as secondary or additive fillers to enhance the properties of nanocomposites, complementing primary fillers that establish the percolation network. While they are limited in independently forming conductive networks, nanoparticles contribute additional functionalities without significantly affecting the composite’s mechanical or electrical performance.

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs)

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are extensively utilized in flexible and soft electronics due to their excellent electrical conductivity and relatively low cost (Fig. 4d)75. Common applications include conductive inks for printed electronics, wearable sensors, and flexible circuits. Their nanoscale size, typically below 100 nm, provides a high surface area-to-volume ratio, facilitating interactions with the surrounding matrix and supporting the formation of conductive networks76. As secondary fillers, AgNPs effectively stabilize connections between primary fillers, enhancing the inter-filler network.

Despite their advantages, AgNPs face limitations due to their low aspect ratio, which results in conductivity being dominated by inter-filler resistance rather than intra-filler pathways. This characteristic reduces their effectiveness in conductive networks, especially under repeated mechanical deformation, where disruptions in inter-filler contact can compromise electrical connectivity. Additionally, AgNPs are prone to oxidation, which degrades their electrical properties over time, and their potential cytotoxicity raises concerns for bioelectronic applications.

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs)

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are highly valued as 0D metallic fillers due to their exceptional electrical conductivity, chemical stability, and biocompatibility (Fig. 4e)77. Although costlier than silver, AuNPs excel in applications where biocompatibility and long-term reliability are critical, such as biomedical devices, biosensors, and implantable electronics78. Unlike many metallic NPs, AuNPs resist oxidation, preserving their electrical properties over extended periods and ensuring durability in demanding environments.

In addition to their stability and conductivity, AuNPs exhibit remarkable optical properties driven by localized surface plasmon resonance. This phenomenon causes free electrons to resonate with light at specific wavelengths, producing intense absorption and scattering effects. These optical characteristics enable their use as highly sensitive optical sensors, where shifts in plasmon resonance wavelength can detect environmental changes, making them invaluable in cancer diagnostics and molecular imaging.

AuNPs also offer extensive versatility in surface functionalization, facilitating the attachment of biomolecules, drugs, or targeting agents. Functionalization with thiol or amine groups enhances their stability and compatibility in biological environments, supporting applications such as targeted drug delivery and biosensors, where precise molecular recognition is essential.

Copper nanoparticles (CuNPs)

Copper nanoparticles (CuNPs) offer a cost-effective alternative to AgNPs and AuNPs, delivering comparable electrical conductivity at a significantly lower price (Fig. 4f)79. Their high thermal conductivity further enhances their utility in energy storage devices, conductive adhesives, and printed electronics79. Additionally, CuNPs exhibit a degree of biocompatibility and biodegradability, making them suitable for environmentally sustainable applications, including transient and bioelectronic devices.

A major limitation of CuNPs is their susceptibility to oxidation, which significantly degrades their electrical performance. Exposure to air or moisture increases resistance and can result in a complete loss of conductivity, posing challenges for stable, long-term use. To mitigate this, protective coatings or stabilizing agents, such as polymers, graphene, or silver layers, are applied to prevent oxidation. These stabilization strategies preserve the NPs’ conductivity and enable reliable performance in demanding applications.

The combination of electrical and thermal conductivity broadens the application scope of CuNPs, particularly in systems requiring efficient heat dissipation, such as flexible electronics. Their relative abundance, low toxicity, and biodegradability further position CuNPs as a sustainable choice, aligning with the growing emphasis on environmentally conscious materials in advanced electronic technologies.

Platinum nanoparticles (PtNPs)

Platinum nanoparticles (PtNPs) are distinguished among 0D metallic nanomaterials for their exceptional catalytic activity, chemical stability, and high conductivity, making them indispensable in applications such as fuel cells, catalysis, sensors, and biosensing80. While their high cost, owing to platinum’s status as a precious metal, limits widespread commercial use, the unparalleled efficiency and durability of PtNPs often justify their expense in specialized applications.

The defining feature of PtNPs is their superior catalytic activity. Platinum’s ability to facilitate redox reactions without degradation makes it invaluable for fuel cells, where it catalyzes the hydrogen oxidation and oxygen reduction reactions. The nanoscale size of PtNPs further enhances their performance by providing a high surface area, enabling efficient energy conversion in fuel cells and other energy systems. Compared to other metals, PtNPs deliver significantly greater catalytic efficiency, making them indispensable in high-performance energy applications.

In addition to their catalytic properties, PtNPs exhibit exceptional chemical stability. Unlike copper, which oxidizes readily, or silver, which tarnishes over time, platinum resists oxidation and corrosion even in harsh chemical or thermal environments. This stability ensures the reliability and longevity of devices like catalytic converters and high-temperature fuel cells. Furthermore, PtNPs are biocompatible and robust, making them suitable for long-term biological applications, including biosensors and drug delivery systems.

Despite these advantages, the high cost and scarcity of platinum pose significant limitations. PtNPs are generally reserved for applications where their unique properties are essential, as their economic and environmental costs hinder broader adoption. Additionally, while PtNPs exhibit high conductivity, their lack of plasmonic properties limits their use in optical applications. These challenges highlight the importance of optimizing PtNPs usage and exploring sustainable alternatives for broader applications.

Quantum dots (QDs)

QDs are nanoscale semiconductor particles that exhibit unique optical and electronic properties due to quantum confinement effects, which occur when the particle size is smaller than the exciton Bohr radius (Fig. 4g). This confinement restricts electron and hole motion, creating discrete energy levels instead of the continuous bands seen in bulk materials. Consequently, QDs can absorb and emit light at specific wavelengths determined by their size, composition, and surface structure. This tunable photoluminescence, combined with high brightness and photostability, makes QDs valuable for applications in displays, solar cells, bioimaging, and sensing (Fig. 4h)81.

QDs are typically composed of semiconductor materials, with cadmium selenide (CdSe), cadmium sulfide (CdS), and lead sulfide (PbS) being among the most widely used due to their favorable bandgap properties. However, concerns over cadmium and lead toxicity have driven interest in more environmentally friendly alternatives, such as indium phosphide (InP) and carbon-based QDs (Fig. 4i, j)82. To enhance optical performance and stability, core-shell structures are often employed; for example, a CdSe core with a zinc sulfide (ZnS) shell improves photostability and quantum yield by reducing surface defects and protecting the core from environmental degradation.

1D metallic nanowires (NWs)

Metallic NWs and nanorods, collectively referred to as NWs, are 1D nanomaterials characterized by high aspect ratios. Their directional geometry facilitates the formation of percolation networks with minimal filler content, making them effective as primary fillers in conductive composites (Fig. 4k)83. NWs also integrate seamlessly into polymeric matrices, maintaining structural integrity while ensuring electrical connectivity under mechanical strain. This unique property enables NWs to slide and rearrange within the matrix, preserving conduction during stretching or bending, which is essential for soft electronics.

NWs share many material properties with metallic NPs but offer the added advantage of precise control over their dimensions. Template-assisted synthesis uses porous templates like anodic aluminum oxide to define NWs’ length and diameter through controlled metal deposition. The polyol process employs solvents like ethylene glycol (EG) and capping agents such as polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) to drive anisotropic growth, particularly effective for AgNWs and CuNWs. Seed-mediated growth introduces seed particles into a growth solution, enabling controlled elongation of AuNWs by adjusting seed concentration and reaction conditions. These methods allow customization of NWs’ properties for diverse applications, including flexible electronics, transparent conductive films, and catalytic systems.

Silver nanowires (AgNWs)

AgNWs share many material characteristics with AgNPs72,84. Their high conductivity and aspect ratio make AgNWs some of the most extensively studied one-dimensional metallic nanomaterials for soft and stretchable electronics85. AgNWs form efficient percolation networks at low filler concentrations, resulting in flexible and stretchable conductive composites with low percolation thresholds. These properties make them ideal for applications such as transparent electrodes, flexible touchscreens, and stretchable circuits52,86.

For example, Qian et al. fabricated ultralight, conductive silver aerogels using AgNWs (Fig. 4l)87. AgNWs with diameters of 50–100 nm and lengths of 40–80 μm, synthesized via the polyol process, served as building blocks for the aerogels. The process involved freezing an AgNW suspension, lyophilizing it to form a porous network, and sintering at 250 °C under hydrogen gas to weld the NWs’ junctions. The resulting aerogel demonstrated an ultralight density of 4.8 mg/cm³, electrical conductivity of 51,000 S/m, and a Young’s modulus of 16.8 kPa, highlighting its exceptional softness and conductivity.

Gold nanowires (AuNWs)

AuNWs offer advantages similar to AgNWs, including excellent conductivity, but with superior chemical stability and biocompatibility, making them suitable for stretchable biosensors, implantable devices, and flexible circuits88. However, their high cost limits commercial scalability, confining their use to high-performance devices where stability and biocompatibility justify the expense.

A major challenge with AuNWs is achieving a high aspect ratio comparable to AgNWs or CuNWs due to gold’s unstable surface diffusion and lack of protective oxidation. Consequently, Au is often synthesized as nanorods rather than true NWs. A promising solution involves coating high-aspect-ratio NWs with gold, as seen in Au-AgNWs, which combine Ag’s conductivity with Au’s stability89,90. However, creating one-dimensional networks of pure Au remains more complex.

For example, Miyamoto et al. developed ultrathin, lightweight, and stretchable gold nanomeshes directly laminable onto human skin without irritating (Fig. 4m)91. This process involved electrospinning PVA nanofibers into a mesh structure, coating it with a 70–100 nm gold layer, and dissolving the PVA scaffold with water to leave a conductive gold network. The nanomesh exhibited exceptional biocompatibility and electrical resistivity of 5.3 × 10⁻⁷ Ω·m, comparable to bulk gold. Although lacking an elastomeric matrix, the nanomesh maintained conductivity under up to 48% strain and remained stable over 500 cycles of 25% strain stretching.

Copper nanowires (CuNWs)

CuNWs present a low-cost alternative to AgNWs and AuNWs, offering excellent electrical and thermal conductivity while being synthesized through relatively inexpensive methods92. These properties make CuNWs attractive for applications in stretchable circuits, sensors, and energy devices93. However, their susceptibility to oxidation significantly reduces conductivity over time. To address this, protective coatings or polymer encapsulation are commonly employed, enabling CuNWs to remain viable for large-scale, cost-effective soft electronics, particularly in consumer electronics and energy storage.

Won et al. developed an annealing-free, scalable CuNWs-based stretchable electrode using a cost-effective process (Fig. 4n)94. CuNWs, averaging 66 nm in diameter and 50 μm in length, were synthesized via a chemical reaction between copper chloride and a capping agent, followed by vacuum filtration to form a conductive film. This film was transferred onto a 40% pre-stretched PDMS substrate, achieving a sheet resistance of 6–12 Ω/sq. While pristine copper films failed under 25% strain, the CuNWs/PDMS film withstood strains up to 90%. Additionally, the PDMS substrate was molded into a helical structure to further enhance strain absorption. The helical CuNWs/PDMS electrode exhibited a minimal relative resistance change of 3.9 under 700% strain and maintained functionality after 100 cycles of 100% strain.

2D metallic nanosheets (NSs)

2D metallic NSs offer unique advantages for applications requiring flat, conductive networks or films due to their broad, plate-like structures and large surface area, which enhance charge and heat transfer (Fig. 4o)95. While NSs excel in forming 2D conductive films, integrating them into 3D percolation networks within elastomeric matrices poses challenges. Aggregation tendencies and their flat geometry can hinder dispersion and disrupt elastomer crosslinking, complicating the balance between conductivity and mechanical integrity.

Several methods are utilized to synthesize metallic NSs while maximizing surface area and ensuring uniform thickness. Liquid-phase exfoliation, a widely used method, involves exfoliating bulk metals into thin sheets using solvents and sonication. Optimizing solvent and surfactant selection minimizes aggregation and enhances dispersion in polymer matrices. Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) enables precise control over NSs’ thickness and lateral dimensions by depositing vaporized metal precursors onto substrates, producing high-quality, defect-free films. Wet chemical synthesis offers versatility, reducing metal salts in solution with surfactants or capping agents to guide 2D growth, allowing for NSs with tunable surface chemistries and improved compatibility with elastomers.

Silver flakes

Silver flakes, as 2D metallic nanomaterials, provide a distinctive approach to achieving conductivity in flexible and stretchable composites96. Their large lateral dimensions enable the formation of continuous conductive pathways at low filler concentrations, making them ideal for conductive adhesives, flexible circuits, and printed electronics. Even under mechanical strain, silver flakes maintain electrical contact through sliding mechanisms97. However, challenges such as high cost and susceptibility to oxidation limit their broader application.

For example, Lv et al. developed a stretchable Ag flake electrode enhanced by human sweat (Fig. 4p)98. Silver flakes dispersed in hydrophilic PUA (HPUA) were used to create conductive ink directly printable onto hydrophilic textiles. Exposure to sweat facilitated a chloride ion-mediated surfactant removal process, improving inter-flake connectivity and reducing resistance from 3.02 to 0.62 Ω. This sweat-induced sintering also enhanced the electrode’s durability, maintaining resistance below 5 Ω through 500 cycles of 30% stretching and showing stable conductivity under 120% strain. The Ag flake-HPUA electrode demonstrates strong potential for wearable electronics, such as soft batteries and current collectors, due to its softness and performance improvements under real-world conditions.

Gold nanosheets (AuNSs)

AuNSs have gained attention for their exceptional conductivity and chemical stability, making them ideal for biomedical devices, sensors, and flexible electronics99. Their 2D structure facilitates the formation of robust percolation networks with high conductivity and durability under mechanical deformation. Despite their advantages, the high cost of gold limits widespread application.

Heo et al. developed elastomeric electrodes incorporating interconnected AuNSs optimized for mechanical resilience and cyclic stretching100. The AuNSs, synthesized via a solution-based process, were transferred onto a PDMS matrix using a hot-pressing method, which removed surface ligands and improved interlayer contact (Fig. 4q). This process produced electrodes with a sheet resistance as low as 0.15 Ω/sq, increasing only slightly to 1.8 Ω/sq under 50% strain. The electrodes demonstrated exceptional durability, maintaining performance over 100,000 stretching cycles. Using these AuNS-based elastomeric electrodes, Heo et al. fabricated resilient electronic devices, including transistors, inverters, and NOR/NAND logic gates, achieving stable field-effect mobilities of 19.8 cm²/V·s even under deformation. These electrodes also proved effective in soft robotic systems, where integrated electronic components retained functionality during various grip motions, highlighting their potential for wearable devices and robotics.

Lim et al. introduced whiskered AuNSs (W-AuNSs) to enhance percolation networks in stretchable electronics101. Featuring whisker-like extensions, W-AuNSs exhibited a significantly lower percolation threshold (1.56 vol%) compared to conventional AuNSs. Nanocomposites incorporating W-AuNSs achieved a conductivity of 91 S/cm at a 2.13% filler volume fraction and maintained stretchability up to 200% elongation at 7.9 vol%. These W-AuNSs also demonstrated stable performance under cyclic testing, with minimal resistance variation. When applied as bioelectrodes for electrophysiological monitoring and stimulation, W-AuNSs provided consistent, high-performance results under mechanical strain, showcasing their suitability for wearable biomedical applications.

Functionalization of metallic nanocomposites

To enhance the performance of metallic nanocomposites, several functionalization techniques have been developed. These techniques aim to improve the electrical conductivity, mechanical properties, and stability of the composites by modifying the structure, composition, or arrangement of the metallic nanofillers.

Secondary fillers

The incorporation of secondary fillers, such as carbon-based nanomaterials, metallic NPs, and ionic liquids, significantly enhances the mechanical strength, stretchability, and conductivity of metallic nanocomposites (Fig. 5a). These fillers infiltrate the gaps between primary fillers or within the polymeric matrix, supporting the percolation network and introducing additional functionalities, such as improved electrochemical performance, antibacterial properties, and reactive oxygen species scavenging. This synergy enables tailored composites optimized for specific applications.

a–d Applying secondary filler. Reproduced with permission89. Copyright 2019, John Wiley & Sons. Reproduced with permission102. Copyright 2017, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission103. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. e–h Applying heterogeneous fillers. Reproduced with permission104. Copyright 2010, AAAS. Reproduced with permission105. Copyright 2018, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission103. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. i–l Phase separation and alignment of the fillers. Copyright with permission105. Copyright 2018, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission106. Copyright 2013, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission107. Copyright 2021, AAAS. m–p Nanofiller welding techniques. Reproduced with permission108. Copyright 2012, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission109. Copyright 2010, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission110. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. q–t Modifying geometry of the fillers. Reproduced with permission111. Copyright 2017, RSC Publishing. Reproduced with permission112. Copyright 2018, RSC Publishing. Reproduced with permission113. Copyright 2008, Springer Nature.

For instance, Sunwoo et al. developed a stretchable nanocomposite integrating Ag–Au core-shell NWs with platinum black (Pt black) as a secondary filler to enhance electrochemical properties for epicardial recording and stimulation89. The addition of 13 wt% Pt black increased the charge storage capacity (CSC) eightfold to 25 mC/cm² and reduced impedance from 2348 to 112 Ω at 40 Hz (Fig. 5b). This composite achieved a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 20.05 dB and maintained durable performance under strain. When implanted in an epicardial mesh, it enabled synchronized biventricular pacing and stable heart rate modulation in rodent models, demonstrating its potential for advanced cardiac support devices.

In situ-formed metallic NPs offer a homogeneous distribution within the matrix, enhancing the performance of nanocomposites. Matsuhisa et al. reported a printable elastic conductor with in situ-generated AgNPs formed during thermal processing102. The AgNPs bridged the gaps between Ag flakes, bolstering conductivity to 6,168 S/cm at 0% strain and 935 S/cm at 400% strain (Fig. 5c). This composite was utilized in fully printed stretchable sensor networks for pressure and temperature monitoring on dynamic surfaces, highlighting its potential for flexible electronics.

Similarly, a study incorporating in situ-formed PtNPs into an SEBS matrix demonstrated improved conductivity and structural integrity103. The homogeneously dispersed PtNPs enhanced the percolation network, achieving a conductivity of 11,000 S/cm, stretchability of 480%, and low impedance (166.5 Ω at 1 kHz) (Fig. 5d). When applied in a rat model, the nanocomposite electrode provided stable biosignal recording, arrhythmia management, and efficient pacing with reduced capture thresholds, underscoring its suitability for advanced bioelectronic devices.

Heterogeneous filler

Incorporating multiple fillers into composites often constrains the performance of primary fillers. To address this, heterogeneous fillers, which integrate multiple materials into a single nanostructure, have emerged as an effective alternative. These fillers combine the strengths of different materials, enhancing overall composite performance. Techniques such as core-sheath structures and doped nanomaterials are commonly employed, with each component contributing distinct properties.

For example, Zhang et al. used a nonepitaxial growth method to synthesize hybrid core-shell NPs, addressing lattice mismatch issues between core and shell materials104. This solution-phase process sequentially deposited metals to form core-shell structures, enhancing stability and electronic properties due to the integration of materials with different crystalline structures (Fig. 5f). These advancements have broadened applications in electronics, catalysis, and energy storage.

In another study, Choi et al. developed AgNW-Au core-sheath NWs to achieve high conductivity, stretchability, and biocompatibility105. Au was galvanically deposited on AgNWs to prevent oxidation, forming a composite integrated into an SBS elastomer (Fig. 5g). The material achieved conductivity of 41,850 S/cm, enhanced to 72,600 S/cm with heat rolling, and stretchability up to 266%, increasing to 840% under strain. The Au coating reduced Ag ion leaching, improving biocompatibility. This composite demonstrated stable performance under strain and oxidative conditions, making it suitable for wearable and implantable bioelectronics.

Sunwoo et al. further advanced this approach with an Ag–Au–Pt core-shell-shell NWs composite incorporating in situ synthesized PtNPs103. This design leveraged silver’s high conductivity, gold’s biocompatibility, and platinum’s low impedance (Fig. 5h). The embossed Pt shell increased surface area, enhancing charge transfer and lowering impedance, while PtNPs within the matrix improved percolation network efficiency. The composite achieved a conductivity of 11,000 S/cm and 500% stretchability, with dual Au–Pt coatings reducing silver ion leaching. Tested in bioelectronic applications, the material demonstrated excellent signal clarity and lower capture thresholds during in vivo cardiac monitoring, highlighting its potential for advanced biosignal monitoring and cardiac rhythm management.

Phase separation and filler alignment

Controlling phase separation and alignment of metallic nanofillers within a matrix significantly enhances composite performance (Fig. 5i). Phase separation allows selective localization of nanofillers, creating efficient percolation networks, while alignment of fillers like AgNWs or AuNWs along the direction of mechanical strain improves conductivity and stretchability. Techniques such as mechanical stretching and magnetic field alignment are commonly used to achieve these effects.

For instance, Choi et al. leveraged phase separation during solvent drying to enhance the properties of an Ag–Au nanocomposite105. By introducing hexylamine, phase separation formed microstructured regions enriched with Ag–Au NWs and SBS elastomer (Fig. 5j). This microstructure reduced the composite’s Young’s modulus and improved softness, enabling stretchability up to ~266% while maintaining high conductivity (41,850 S/cm). Without hexylamine, the composite exhibited lower stretchability and a homogenous structure, demonstrating the critical role of phase separation in balancing mechanical and electrical properties.

Kim et al. employed vacuum-assisted flocculation (VAF) to integrate citrate-stabilized AuNPs into a PU matrix, enhancing phase separation and self-organization106. This approach produced composites with stretchability up to 486%, as NPs formed conductive pathways under strain (Fig. 5k). VAF composites exhibited larger PU domains, optimizing stretchability, while layer-by-layer composites offered higher initial conductivity (11,000 S/cm) due to uniform NPs dispersion. SAXS and TEM analysis revealed that NPs alignment under strain improved conductivity by lowering the percolation threshold.

Jung et al. developed a highly conductive and stretchable AgNWs nanomembrane using a float assembly method107. This process aligned AgNWs at the water–oil interface through Marangoni flow, creating a compact monolayer embedded in an ultrathin elastomer membrane (Fig. 5l). The aligned network achieved exceptional conductivity (165,700 S/cm) and stretchability, withstanding strains over 1,000%. This structural design efficiently dissipated strain through elastomeric regions, making the nanomembrane suitable for advanced soft electronic applications.

Welding of metallic nanofillers

Welding techniques, such as thermal annealing and chemical welding, significantly enhance the connectivity between metallic nanofillers by reducing contact resistance and boosting composite conductivity (Fig. 5m)87. These methods are particularly beneficial for NW networks, where individual wires can lose contact under mechanical strain.

Garnett et al. developed a self-limited plasmonic welding technique for AgNWs junctions using light-induced plasmonic heating to generate localized heat at contact points108. This process, driven by a tungsten halogen lamp, achieved epitaxial recrystallization at junctions without damaging surrounding areas (Fig. 5n). Junction resistance was reduced by over three orders of magnitude within 60 seconds, yielding electrical performance comparable to continuous NWs. The self-limiting nature of the process prevented over-welding, ensuring structural integrity.

Lu et al. demonstrated cold welding of ultrathin AuNWs without localized heating109. By applying minimal mechanical pressure, single-crystalline AuNWs (3–10 nm in diameter) were seamlessly bonded via surface atom diffusion and oriented attachment (Fig. 5o). Welded junctions maintained crystal orientation and exhibited mechanical strength (~580 MPa) and resistivity (~298.1 Ω·nm) comparable to pristine NWs. The technique was also applicable to Ag–Ag and Au–Ag junctions, highlighting its versatility for nanoscale interconnects in electronic systems.

Liu et al. introduced a capillary-force-induced cold welding method for AgNW films110. Moisture applied to the films created liquid bridges at junctions, drawing wires together as the liquid dried (Fig. 5p). This simple process reduced sheet resistance from 2.25 × 10⁵ Ω/sq to 179 Ω/sq while maintaining optical transparency (<1% change). Treated films showed enhanced flexibility, enduring up to 100% strain with minimal resistance increase (~1.5 times), demonstrating the technique’s effectiveness for flexible electronics.

Filler geometry modification

Modifying the geometry of metallic nanofillers offers a promising route to enhance their performance in soft electronics by improving filler contact and optimizing the percolation network (Fig. 5q). Branched or curved NWs, for instance, provide additional contact points between fillers, enhancing conductivity and mechanical compliance. These geometrical modifications enable tailored nanocomposites suited for applications like stretchable sensors and flexible circuits.

Lim et al. demonstrated the formation of curved AgNWs through a spray-coating process that induced elasto-capillary interactions111. High-speed spraying generated micrometer-sized liquid droplets, within which AgNWs were elastically deformed into curved shapes as the droplets dried, forming AgNW rings instead of linear structures (Fig. 5r). The curved networks, embedded in a PDMS matrix, exhibited exceptional durability, maintaining stable resistance over 5000 cycles of 30% strain. In contrast, traditional linear AgNW networks showed breakage and increased resistance under similar conditions, highlighting the superior electromechanical stability of the curved structures.

Another approach involved synthesizing ultra-long AgNWs exceeding 100 µm via a solvothermal method, yielding a high aspect ratio critical for efficient percolation network formation112. The extended lengths reduced inter-NWs junctions, minimizing resistive losses and enhancing connectivity (Fig. 5s). These AgNW films, applied as transparent conductive layers on PET substrates, achieved a low sheet resistance of ~19 Ω/sq and high optical transmittance (88%). The dense, stable networks outperformed conventional materials like ITO in both flexibility and durability.

Zhu et al. explored chiral branched PbSe NWs grown through the Eshelby Twist, which combined vapor-liquid-solid and screw dislocation-mediated mechanisms113. The resulting structures exhibited branching and chiral motifs, with perpendicular branches twisting around central NWs due to axial dislocations (Fig. 5t). While not directly tested for percolation networks, these branched configurations suggest improved connectivity and enhanced electron transport potential, ideal for applications requiring robust, interconnected NW networks.

Liquid metals (LMs)

LMs represent a unique class of materials for intrinsically soft electronics, combining metallic conductivity with fluid-like mechanical properties114. These materials offer exceptional electrical conductivity, comparable to traditional solid metals, which is essential for efficient circuit operation. Their fluid nature provides intrinsic deformability, enabling them to conform to various shapes and withstand mechanical forces such as stretching, twisting, or compressing. These properties make LMs particularly suitable for applications in soft robotics, wearable electronics, and flexible sensors, where conventional rigid materials are inadequate.

Despite these advantages, LMs face several challenges in practical applications. Certain LMs, such as mercury, are toxic115, while others, like cesium, are radioactive116, or highly flammable, such as sodium-potassium alloys117. Additionally, surface oxidation can hinder the electrical properties of some LMs. Furthermore, precise patterning and reliable encapsulation methods are critical to prevent leakage and ensure safe operation across diverse environments. The following sections explore the most commonly used LMs, their inherent limitations, and the innovative techniques developed to integrate them into soft electronic devices effectively.

Commonly used LMs

Several LMs are commonly used in soft electronic applications. These metals are typically chosen based on their electrical properties, melting points, and ease of processing. The most prominent examples include gallium and its alloys, such as eutectic gallium-indium (EGaIn) and gallium-indium-tin (Galinstan).

Gallium

Gallium (Ga) is a widely used liquid metal in soft electronics, primarily due to its low melting point of 29.76 °C, allowing it to remain liquid at or near room temperature (Fig. 6a)118. Gallium’s relative abundance, low toxicity, and high electrical conductivity make it a safer and efficient alternative to hazardous materials like mercury. These properties render gallium ideal for applications such as stretchable circuits, flexible antennas, and wearable sensors.

a–d Gallium and their applications. Reproduced with permission118. Copyright 2014, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission119. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission120. Copyright 2021, John Wiley & Sons. e–h EGaIn and their applications. Reproduced with permission121. Copyright 2014, National Academy of Science. Reproduced with permission114. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission122. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission123. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature. i–l Ga-In-Sn alloy and their applications. Reproduced with permission124. Copyright 2016, John Wiley & Sons. Reproduced with permission125. Copyright 2014, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission126. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission127. Copyright 2023, John Wiley & Sons. m Mercury. Reproduced with permission128. Copyright 2013, Springer Nature. n Cesium. o, p Sodium-potassium alloy. Reproduced with permission130. Copyright 2014, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission117. Copyright 2023, John Wiley & Sons.

A key challenge with pure gallium is its tendency to form a thin oxide layer when exposed to air. This nanometer-scale oxide layer increases electrical resistance, potentially limiting gallium’s effectiveness in applications requiring ultra-low resistivity. However, the oxide layer also enhances structural integrity, enabling the formation of stable liquid metal structures. Strategies such as encapsulation and surface treatments have been developed to control oxide formation and optimize gallium’s performance in electronic devices.

For instance, Wang et al. introduced supercooled liquid gallium (SLGa) to create intrinsically stretchable electronics119. Encapsulating gallium with low-surface-energy materials like PDMS prevented crystallization, maintaining its liquid state down to -22 °C. This enabled the fabrication of stretchable circuits and ECG patches capable of stable operation in cold conditions and underwater environments. Using spray-printing, uniform SLGa microelectrode arrays with low impedance and high conformability to human skin were created. These circuits demonstrated stable resistance under strains up to 50%, highlighting their suitability for flexible and wearable electronics (Fig. 6b).

In another study, Dejace et al. developed highly stretchable and transparent electronics by patterning microscale gallium conductors within a PDMS substrate120. Through soft lithography and thermal evaporation, high-aspect-ratio gallium channels as narrow as 2 µm were fabricated, achieving up to 89.6% optical transparency at 550 nm and a sheet resistance as low as 4.3 Ω/sq. This precise patterning enabled scalable designs for large-area applications (Fig. 6c). The patterned conductors exhibited stable electrical performance under strain, with resistance increasing by less than 0.2-fold after 50% strain cycles. By adjusting the grid pitch, the transparency and conductivity of the gallium structures were fine-tuned, making them suitable for wearable and transparent electronics (Fig. 6d).

EGaIn (eutectic gallium-indium)

EGaIn, a eutectic alloy of gallium (75%) and indium (25%), has a melting point of approximately 15.7 °C, making it liquid at room temperature (Fig. 6e)121. Compared to pure gallium, EGaIn offers enhanced properties such as lower viscosity and improved stability. Its high electrical conductivity and ease of processing make it ideal for applications in stretchable electronics, soft robotics, and flexible circuits. While EGaIn forms a thin oxide layer upon air exposure, which acts as a self-passivating barrier to further oxidation, this layer can also pose challenges for consistent conductivity, particularly in high-frequency applications. Nevertheless, its low toxicity compared to other LMs makes EGaIn highly suitable for wearable and biomedical devices.

For instance, Lee et al. utilized meniscus-guided printing to create high-resolution patterns of polyelectrolyte-attached liquid metal particles prepared from EGaIn (Fig. 6f)114. This technique enabled stable, post-processing-free patterning with resolutions as fine as 50 µm. The printed films exhibited an initial conductivity of 1.5 × 10⁶ S/m and endured up to 500% strain while maintaining minimal resistance changes under 10,000 cycles of testing. This versatile approach allowed direct printing on substrates like PDMS and hydrogels, facilitating applications in wearable e-skin and customizable ECG sensors.

In another study, Kim et al. introduced an imbibition-induced selective wetting method to pattern EGaIn on microstructured copper surfaces (Fig. 6g)122. Using HCl vapor to remove the oxide layer, the researchers achieved uniform, oxide-free coating and precise patterns without complex processing. The resulting EGaIn films demonstrated stable conductivity, maintaining low resistance under 70% strain with a gauge factor of 2.6. Durability was further confirmed through 4,000 cycles of 30% strain.

Additionally, researchers developed 3D flexible electronics using the regulated plasticity of a Ga–10In alloy (gallium with 10% indium by weight) (Fig. 6h)123. By exploiting its solid–liquid phase transition, the alloy was shaped into complex 3D conductive structures in its solid form and encapsulated in the elastomer. Above 22.7 °C, the alloy transitioned to a liquid state, ensuring flexibility and temperature stability. These 3D circuits demonstrated robust performance, with strain sensors achieving a gauge factor exceeding 2000 and maintaining electrical connections after 20,000 bending cycles, showcasing their potential for advanced stretchable devices.

Galinstan (gallium-indium-tin alloy)

Galinstan, a eutectic alloy of gallium, indium, and tin, remains liquid at sub-zero temperatures due to its exceptionally low melting point of approximately 11 °C (Fig. 6i)124. Its non-toxic, environmentally friendly properties make it suitable for applications in medical devices, consumer products, and thermal management systems. Galinstan shares similarities with gallium and EGaIn, forming a surface oxide layer upon air exposure. However, its low viscosity and high fluidity make it ideal for deformable conductive materials, such as stretchable interconnects, flexible displays, and fluidic sensors.

For instance, Ota et al. developed deformable liquid-state heterojunction sensors using Galinstan within PDMS microfluidic channels (Fig. 6j)125. By pairing Galinstan with ionic liquids and controlling channel dimensions, they created stable liquid–liquid junctions. The sensors exhibited high flexibility, with stable electrical properties under 90% strain, and achieved a temperature sensitivity of 3.9% per °C, outperforming conventional solid-state sensors. They also showed high responsiveness to humidity (1.7% per 1% increase) and oxygen concentration (1.0% per 1% increase).

In another example, Lin et al. fabricated flexible, conductive textiles by injecting Galinstan into perfluoroalkoxy alkane tubing, forming liquid metal fibers with a conductivity of 3.46 × 10⁶ S/m (Fig. 6k)126. These fibers were embroidered onto fabrics to create durable electronic textiles capable of withstanding 10,000 bending cycles and multiple washes. The textiles enabled wireless communication and power transfer, achieving a quality factor of 44.4 at 13.56 MHz for textile-based inductors, outperforming conventional threads.