Abstract

2-Pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid (PDC) is a lignin-derived biometabolic intermediate that can be produced on a large scale by using transforming bacteria and can be directly polymerized by polycondensation with diols to produce biomass polyesters. In the present study, a variety of PDC-based polyesters were successfully synthesized by direct polymerization between PDC and diols with different alkyl chain lengths. The thermal, crystalline, and mechanical properties of a series of PDC polyesters were fully characterized. The biodegradability of the PDC polyesters was investigated by biodegradation tests in a confined simulated environment using pond water. There was a clear correlation between the biodegradation rate, alkylene spacer length, and polymer hydrophilicity. In addition, the PDC polyesters exhibited excellent adhesive properties to various metals, and their adhesive properties gradually decreased with a decrease in the PDC content in the polymers. The excellent adhesion to an aluminum plate with the lap-shear strength of up to 15.26 MPa was demonstrated and this value is comparable to those of the-state-of-the-art commercial quick-drying metal adhesives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

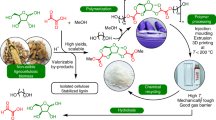

The urgent need to transition to a sustainable, carbon-neutral society has led to a research boom in the development of bio-based renewable resources as viable alternatives to petrochemicals1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Among the range of bio-based materials being explored, lignin is a particularly promising candidate due to its ubiquity and abundance in nature. Lignin is a complex organic polymer whose unique structure is characterized as a three-dimensional network with rich aromatic components, rendering it an attractive feedstock for the production of a wide range of high-value chemicals and materials9,10,11,12,13,14,15. However, the structural complexity of lignin that makes it so appealing also presents significant technical challenges for its valorization. In recent years, a promising strategy to the exploitation of lignin has been the use of microorganisms to selectively depolymerize lignin and convert it into valuable small molecular compounds16,17,18,19,20. In a previous study, lignin-derived aromatic compounds were successfully converted into 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid (PDC) on a large scale using engineered Pseudomonas putida strains21. PDC is a multifunctional compound consisting of a polar pseudo-aromatic pyrone ring and two carboxyl groups, making it an ideal monomer for the synthesis of a variety of polymers and polymeric materials22,23,24. It has been shown that PDC can be dehydrated and condensed with diols to produce a variety of PDC polyesters, which show good mechanical and biodegradable properties24,25,26.

Metal adhesives have garnered significant attention due to their unique combination of functional properties, including high strength, toughness, and durability, rendering them valuable industrial materials in the fields of consumer goods and aerospace. However, there are often limitations for traditional metal adhesives, such as acrylates and polyurethanes, because they are typically derived from non-renewable petroleum resources. To address these issues, researchers have been actively developing sustainable metal adhesives derived from bio-based materials27,28,29. Many of these bio-based adhesives are biodegradable, non-toxic, and free of volatile organic compounds, thereby minimizing their environmental impact.

Our previous studies have shown that PDC-based polymers, such as P(PDC2) (m = 2) and P(PDC3) (m = 3) (Scheme 1), form covalent bonds with the surface of metals, glasses, and wood upon heating, which are the origin of strong adhesive properties30,31,32,33. The development of PDC-based polymeric adhesives represents a significant advancement in the pursuit of sustainable bio-based alternatives to traditional petrochemicals and holds great potential to contribute to the transition toward a more circular and carbon-neutral economy.

In our previous studies, we successfully synthesized functional PDC polyesters, abbreviated P(PDC2) and P(PDC3) (Scheme 1), by the direct polycondensation of PDC with ethylene glycol and 1,3-propanediol, respectively, and investigated their biodegradation properties and adhesion to wood34. However, P(PDC2) and P(PDC3) are difficult to process due to their hard and brittle nature, limiting their applicability beyond adhesive formulations. To overcome this limitation, the present study explores the use of longer chain diols to synthesize functional PDC-based polyesters with improved processability. We investigated the thermal and mechanical properties of PDC polyesters with varying alkylene chain lengths, as well as their crystalline characteristics. Given that P(PDC2) and P(PDC3) have demonstrated adhesive properties to wood, we further examined the adhesive performance of PDC polyesters with different alkylene chain lengths on various metals and analyzed the results in detail. Additionally, considering that PDC is a biodegradable bio-based material, we evaluated the biodegradability of the synthesized PDC polyesters in natural pond water.

Materials and methods

Materials

2-Pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid (PDC) was prepared from vanillic acid using an engineered P. putida strain, as reported previously21. Ethylene glycol was purchased from Kanto Chemical Co., Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). Antimony(III) oxide was purchased from Fujifilm Wako, Co. (Osaka, Japan). 1,3-Propanediol was purchased from Tokyo Kasei Kogyo Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). 1,4-Butanediol, 1,6-hexanediol, 1,8-octanediol, and 1,12-dodecanediol were purchased from Tokyo Kasei Kogyo Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Aron Alpha® High-speed® EX (adhesive with α-cyanoacrylate) was purchased from Toagosei Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). All reagents were used without further purification.

Pond water and bottom soil were collected from Senzokuike Park in Ota City (Tokyo, Japan). They were used on the day of sampling. For preparation of the standard test medium referring to ISO 14851:1999, ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), anhydrous potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4), anhydrous dipotassium hydrogen phosphate (K2HPO4), magnesium sulfate heptahydrate (MgSO4·7H2O), calcium chloride dihydrate (CaCl2·2H2O), and iron(III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O) were purchased from Kanto Chemical Co., Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). Disodium hydrogen phosphate dihydrate (Na2HPO4·2H2O) was purchased from Tokyo Kasei Kogyo Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). The PET pellets were supplied by the Toray Co. (Tokyo, Japan). Cellulose (microcrystalline) was purchased from Kanto Chemical Co., Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). All reagents were used without further purification.

Measurements

Nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectra were recorded on a JEOL (Tokyo, Japan) model 400YH spectrometer at 20 °C. All chemical shifts are reported in parts per million downfield from SiMe4, using the solvent’s residual signal as an internal reference. The resonance multiplicity was described as s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), and m (multiplet). Fourier transform infrared spectra (FT-IR) were recorded on a JASCO (Tokyo, Japan) FT/IR-4200 spectrometer. Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) was measured at 40 °C using a JASCO HSS-1500 system with a refractive index (RI) detector, an absorbance detector (UV-2075 Plus), and two Shodex GPC KF-803 columns (8.0 mm I.D. × 300 mm L). Tetrahydrofuran (THF) and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) were used as the eluent at the flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1 at 40 °C. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were recorded under a nitrogen flow on a Rigaku (Tokyo, Japan) Thermo plus TG8120 and DSC8230, respectively, at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1, from 20 °C to 500 °C for TGA and from 0 °C to 260 °C for DSC. X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed using a Rigaku (Tokyo, Japan) benchtop powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) instrument MiniFlex at the Core Facility Center, Institute of Science Tokyo. Contact angle measurements were performed using an SEO (Gyeonggi, Korea) Phoenix 150S analyzer by adding a water droplet on the PDC-based polyester film surfaces.

Mechanical property

PDC-based polyester films were prepared by hot pressing at 10 MPa and curing under vacuum for 10 min. To control the film thickness, a 0.30 mm thick Teflon spacer was used. This was used to keep the thickness of PDC-based polyester films at 0.30 ± 0.05 mm. After slowly cooling to room temperature, the PDC-based polyester films were cut into dumbbell-shaped specimens using an SDL-100 (Japan) SD-type lever-controlled sample cutter. The specimens were then subjected to strain-stress (S-S) analysis at 23 ± 2 °C. The narrow section (10 mm ± 0.5 mm) of the dumbbell-shaped specimens served as the testing area.

Injection molding of PDC-based polyester (P(PDC6)) was carried out using an OriginalMind Inc. (Nagano, Japan) manual injection molding machine INARI M06. The PDC-based polyester was cut into pellets with a maximum diameter of less than 0.5 cm to facilitate loading into the injection molding machine and to make it easier to melt. The column of the injection molding machine was heated to 250 °C to melt the polymer. After injection, the PDC-based polyester was subjected to a 5-min holding pressure to prevent voids. The mold and the PDC-based polyester were cooled to room temperature by a Cooler of INARI M06 after injection molding.

Adhesive property

Tensile lap shear strength measurements were performed according to JIS K 6850-1994 for measurements of adhesive properties with a Shimadzu Co. (Tokyo, Japan) autograph AGS-10kNX STD. The size of the metal plate pieces (Al, Fe, or Cu) used for the adhesive measurements was 25.0 mm × 100.0 mm × 1.6 mm. The surface of metal plates was washed under sonication with a series of solvents, and they were then treated with a Technovision Inc. (Saitama, Japan) UV-O3 Cleaner UV-208 for 600 s. Approximately 0.3 g of PDC-based polyester (P(PDCm)) was cast on the surface of a metal plate. A set of two plates was placed in contact with each other by hot pressing at 10 MPa and cured for one hour under vacuum. To control the reliability of the adhesive conditions in each test environment, a 0.20 mm thick Teflon spacer was used between the metal plates. This was used to keep the thickness of the adhesive layer at 0.20 ± 0.02 mm. To eliminate residual stresses within the adhesive itself during each measurement, the metal plates and the adhesive were slowly cooled to room temperature after hot-pressing. The failure force was measured at room temperature at the rate of 1 mm min−1. To balance the forces, an additional set of metal plates was used when measuring the tensile lap shear strengths. The adhesive strengths were calculated as the failure force divided by adhesive area (25.00 ± 1.00 mm × 10.00 ± 1.00 mm).

Biodegradation tests

Biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) tests were performed to evaluate the biodegradability of PDC, bishydroxyethyl-substituted PDC (BHPDC), P(PDC2), P(PDC3), P(PDC4), P(PDC6), P(PDC8), P(PDC12), and PET in a simulated natural environment using an OxiTop IS-6 (WTW GmbH, Weilheim in Oberbayern, Germany) referring to the ISO 14851:1999 standard. Note that the BOD tests of PDC, BHPDC, P(PDC2), and P(PDC3) were also previously reported35. The following buffer solution was prepared: solution A; KH2PO4, 8.5 g·L−1; K2HPO4, 21.75 g·L−1; Na2HPO4, 33.4 g·L−1; NH4Cl, 0.5 g·L−1, solution B; MgSO4·7H2O, 22.5 g·L−1, solution C; CaCl2·2H2O, 36.4 g·L−1, solution D, FeCl3·6H2O, 0.25 g·L−1. To prepare 1 L of the standard test medium, 10 mL of solution A and 1 mL each of solutions B, C, and D were added to 500 mL of water, then the volume was adjusted to 1 L. For the BOD test, 10.0 g of soil from the bottom of the pond was dispersed in the standard test medium and stirred for at least 10 min. After standing for 2 h, the supernatant was filtered and used as the soil inoculum.

Briefly, the biodegradation tests were performed in the dark, using closed 250-mL vessels incubated at 25 °C. Approximately 100 mL of standard test medium was added to each vessel. Then, about 10 mg of the test material and 2% (v/v) soil inoculum were added to the respective vessels, while some vessels without test material served as blanks. Each group consisted of at least three vessels. Evolved CO2 was trapped by sodium hydroxide (350 mg) inside the vessels. The oxygen consumption in the vessel was determined from the pressure changes in the closed vessels. The biodegradability was estimated using the following equation:

where BODsample (mg/L) represents the amount of oxygen consumption from a vessel and test material at time t, BODblank (mg/L) is the average amount of oxygen consumption of the blank at time t, and ThOD (mg/L) is the maximum amount of oxygen consumption that could be theoretically consumed by the test material based on the amount of added carbon.

For the biodegradation tests of polymers, P(PDC2), P(PDC3), and P(PDC4) were ground into powder and sieved to obtain particles smaller than 250 μm. P(PDC6), P(PDC8), and P(PDC12) were cut into pellets and similarly sieved to control particle size below 250 μm.

Synthesis

P(PDC2): PDC (18.41 g, 0.100 mol), antimony trioxide (1 mol%, 292 mg, 1 mmol), and ethylene glycol (5.58 mL, 0.1 mol) were taken in a round bottom flask. After stirring at 140 °C for 0.5 h to completely dissolve PDC in ethylene glycol, the temperature was increased to 180 °C and the mixture was stirred for another 0.5 h. The mixture was then cooled to room temperature to yield P(PDC2) (20.84 g, 99.16%) as a yellow solid.

IR (neat): ν = 3096, 1721, 1638, 1563, 1398, 1375, 1328, 1231, 1171, 1117, 1029, 9976, 871, 759, 710, 670, 629, 620, 609, 580, 571, 563, 554, 534, 516, 502 cm−1.

P(PDC3): PDC (18.41 g, 0.100 mol), antimony trioxide (1 mol%, 292 mg, 1 mmol), and 1,3-propanediol (7.25 mL, 0.1 mol) were taken in a round bottom flask. After stirring at 140 °C for 0.5 h to completely dissolve PDC in 1,3-propanediol, the temperature was increased to 180 °C and the mixture was stirred for another 0.5 h. The mixture was then cooled to room temperature to yield P(PDC3) (21.48 g, 95.79%) as an orange solid.

IR (neat): ν = 3103, 2968, 1716, 1640, 1562, 1461, 1398, 1330, 1238, 1168, 1110, 1025, 865, 758, 709, 665, 629, 613, 606, 597, 580, 566, 555, 546, 531 517 cm−1.

P(PDC4): PDC (4.600 g, 0.025 mol), antimony trioxide (1 mol%, 73 mg, 0.25 mmol), and 1,4-butanediol (2.22 mL, 0.025 mol) were taken in a round bottom flask. After stirring at 140 °C for 0.5 h to completely dissolve PDC in 1,4-butanediol, the temperature was increased to 180 °C and the mixture was stirred for another 0.5 h. The mixture was then cooled to room temperature to yield P(PDC4) (5.706 g, 95.88%) as a dark orange solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, THF-d8, 293 K): δ = 7.22 - 7.16 (m, nH), 6.92 - 6.81 (m, nH), 4.26 - 4.12 (m, 4nH), 1.79 - 1.66 (m, 4nH); IR (neat): ν = 3099, 2976, 2899, 1706, 1638, 1562, 1466, 1397, 1329, 1244, 1212, 1171 1113, 1024, 997, 944, 870, 760, 711, 671, 616, 603, 564, 548, 532, 519, 512, 504 cm−1.

P(PDC6): PDC (4.600 g, 0.025 mol), antimony trioxide (1 mol%, 73 mg, 0.25 mmol), and 1,6-hexanediol (2.954 g, 0.025 mol) were taken in a round bottom flask. After stirring at 140 °C for 0.5 h to obtain a homogeneous solution of PDC and 1,6-hexanediol, the temperature was increased to 180 °C and the mixture was stirred for another 0.5 h. The mixture was then cooled to room temperature to yield P(PDC6) (6.116 g, 91.94%) as an orange solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, THF-d8, 293 K): δ = 7.28 - 7.21 (m, nH), 6.96 - 6.89 (m, nH), 4.28 - 4.18 (m, 4nH), 1.74 – 1.60 (m, 4nH), 1.45 - 1.38 (m, 4nH); IR (neat): ν = 2969, 2939, 2860, 1723, 1641, 1563, 1462, 1433, 1365, 1330, 1231, 1217, 1171, 1110, 967, 889, 866, 777, 760, 731, 709, 670, 631, 616, 558, 548, 515, 506 cm−1.

P(PDC8): PDC (4.600 g, 0.025 mol), antimony trioxide (1 mol%, 73 mg, 0.25 mmol), and 1,8-octanediol (3.656 g, 0.025 mol) were taken in a round bottom flask. After stirring at 140 °C for 0.5 h to obtain a homogeneous solution of PDC and 1,8-octanediol, the temperature was increased to 180 °C and the mixture was stirred for another 0.5 h. The mixture was then cooled to room temperature to yield P(PDC8) (6.9294 g, 94.28%) as a yellow solid.

IR (neat): ν = 3102, 2927, 2856, 1723, 1638, 1561, 1540, 1465, 1416, 1395, 1329, 1240, 1167, 1109, 997, 960, 870, 778, 761, 710, 864, 621, 571, 555, 547, 533, 522, 515, 506 cm−1.

P(PDC12): PDC (4.600 g, 0.025 mol), antimony trioxide (1 mol%, 73 mg, 0.25 mmol), and 1,12-dodecanediol (5.058 g, 0.025 mol) were taken in a round bottom flask. After stirring at 140 °C for 0.5 h to obtain a homogeneous solution of PDC and 1,12-dodecanediol, the temperature was increased to 180 °C and the mixture was stirred for another 0.5 h. The mixture was then cooled to room temperature to yield P(PDC12) (8.052 g, 92.01%) as a light yellow solid.

IR (neat): ν = 3103, 2922, 2852, 1867, 1725, 1638, 1560, 1541, 1522, 1507, 1465, 1416, 1396, 1329, 1241, 1168, 1109, 1027, 996, 964, 888, 868, 797, 778, 761, 710, 620, 612, 572, 556, 547, 522, 515, 504 cm−1.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization

We have reported the synthesis of P(PDC2) and P(PDC3) in a previous study35. In this study, we utilized diols with longer alkylene chains in the polymerization and performed a comprehensive characterization of the resulting polymers (Scheme 1). Among them, P(PDC4) exhibited properties similar to P(PDC2) and P(PDC3), characterized by a brittle texture and solid powder form. In contrast, P(PDC6), P(PDC8), and P(PDC12) are tougher, with the products appearing as lumps. In addition, P(PDC8) and P(PDC12) displayed very low solubility in common organic solvents and thus were not subjected to NMR and GPC analyses. In contrast, P(PDC4) and P(PDC6) showed partial solubility in both THF and DMF, allowing characterization by 1H-NMR (Supplementary Figs. S1, S2). The hydrogen peaks from the alkylene chain of the diol appear between δ = 1-2 and 4.2 in the reaction product, while the hydrogens from the pyrone ring of PDC are clearly observed between δ = 6.9 and 7.2. These signals confirm that the reaction proceeded smoothly and the target product was successfully obtained. GPC analysis using THF as the eluent showed that the molecular weights of the polymers obtained from this reaction were consistent with previously reported values, with Mn ranging from 2000 to 3000. When the eluent was changed to DMF, higher molecular weights Mn ranging from 4000 to 6000 were observed (Table 1). P(PDC8) and P(PDC12) could not be characterized by GPC because they were insoluble in both THF and DMF. Additionally, Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy was performed on all the polymers synthesized in this study (Fig. 1). The intensity of the polymer peaks at 3040 cm−1 and 2960 cm−1 gradually increased with the lengthening of the alkylene chains of the diols, confirming an increasing proportion of alkylene chains in the polymers. This also indicates that the reaction between the diols and PDC proceeded successfully, yielding the target polyesters.

X-ray diffraction patterns

To study the crystallinity of the PDC-based polyesters, X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed (Fig. 2). All samples exhibited a broad peak near 2θ = 20°, indicating the presence of an amorphous fraction. Since the polymers were not purified to remove the catalyst Sb2O3, sharp peaks corresponding to Sb2O3 were observed at 2θ = 27.7°, 32.2°, 46.1°, and 54.8° in some of the PDC-based polyesters. Starting from P(PDC6), a small peak appeared at 2θ = 8.2°, which can be attributed to crystallization, as the alkylene chain length becomes sufficient to induce crystallinity. In P(PDC8), this peak became more pronounced and shifted to outward to 2θ = 7.5°. For P(PDC12), a sharp peak was observed at 2θ = 5.8°, indicating increased crystallinity with longer alkylene chains. These results suggest that P(PDC12) exhibits the highest degree of crystallinity among the polyesters synthesized in this study.

Thermal properties

We have analyzed the resulting polyesters by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements (Table 1). TGA analysis revealed that the onset temperature of thermal decomposition decreases as the alkylene chain length increases from P(PDC2) to P(PDC4) (Fig. 3). However, beginning with P(PDC6), the thermal decomposition temperatures of the polymers exceeded that of P(PDC2), reaching a maximum of 308.5 °C for P(PDC12). This trend is likely related to the crystalline properties of the polymers. As indicated by previous XRD analyses, crystallinity begins to emerge in the polymers starting from P(PDC6), which may contribute to the increased onset decomposition temperatures. P(PDC8) exhibited similar crystallinity to P(PDC6), whereas P(PDC12) possessed the highest degree of crystallinity among the synthesized polyesters, corresponding to its highest onset thermal decomposition temperature.

DSC analysis was also performed to investigate the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the polymers (Supplementary Fig. S3). The results clearly showed that Tg decreases with increasing alkylene chain length. P(PDC2) to P(PDC4) displayed similar Tg values, while a sharp decrease was observed starting from P(PDC6), dropping from 78.9 °C in P(PDC4) to 49.5 °C in P(PDC6). Given that the Tg values of PET and PBT are ~60~80 °C and 37~53 °C, respectively, the PDC-based polyesters exhibit comparable or even superior thermal stability. The Tg values of P(PDC6) to P(PDC12) were comparable, ranging from 40 to 50 °C, with P(PDC12) showing the lowest Tg among the synthesized polyesters. Although XRD analysis indicated the emergence of crystallinity beginning with P(PDC6), DSC analysis did not reveal any distinct crystalline melting or crystallization peaks for P(PDC6) to P(PDC12) during either heating or cooling cycles. To gain insight into the melting points (Tms), the empirical rule of Tm/Tg ~ 1.5 was applied36. The melting of P(PDC2) and P(PDC3) occurs near their thermal decomposition temperatures. However, with increasing alkylene chain length, distinct polymer melting transitions appear to form. This feature was utilized in the injection molding experiment (vide infra).

Mechanical properties

The mechanical properties of the synthesized PDC-based polyesters were evaluated using hot-pressed films. For P(PDC2) to P(PDC4), it was extremely difficult to assess mechanical properties due to the brittleness and fragility of the resulting polymer films. In particular, P(PDC2) could not even form an intact film through hot pressing. In contrast, P(PDC6) to P(PDC12) exhibited good film-forming ability, and the resulting films showed measurable strength and toughness (Supplementary Figs. S4, S5). Therefore, mechanical testing was conducted on P(PDC6) to P(PDC12) (Fig. 4 and Table 2). Among them, P(PDC6) displayed the highest tensile strength of 27.6 MPa. As the alkylene chain length increased, the ductility of the polymers improved, while their tensile strength gradually decreased.

Injection molding is a crucial step in the industrial processing of plastic products. Therefore, it is important to evaluate whether PDC-based polyesters are suitable for this process. In this study, P(PDC6) was selected as a representative sample to assess its injection moldability and potential to form well-defined shapes, as its melting point, estimated to be 210 °C using the empirical formula Tm/Tg ~1.536, is sufficiently lower than the thermal decomposition temperature. For comparison, a polypropylene product was also fabricated by using the same injection molding setup (Supplementary Fig. S6). Although the P(PDC6) molded product exhibited some defects, the injection molding process itself proceeded smoothly, demonstrating that PDC-based polyesters have potential for industrial processing. However, it should be noted that the injection molding of PDC polyesters is less straightforward than that of conventional plastics, likely due to their adhesive nature to metals when heated.

Adhesive properties

In our recent study, we reported the adhesive properties of P(PDC2) and P(PDC3) to wood. In the present work, it was important to investigate the adhesion of PDC-based polyesters to metal surfaces, as PDC undergoes ring opening at around 180–190 °C, enabling covalent bonding with surface oxygen atoms on metals32,37. To evaluate this, we measured the adhesive strength of PDC polyester to three metals: aluminum, iron, and copper (Supplementary Fig. S7), by hot pressing under vacuum at 200 °C to induce ring opening (Fig. 5 and Table 3). For comparison, we also tested the adhesive properties of a commercial quick-drying metal adhesive on the same metals.

Overall, as the alkylene chain length increased, the proportion of PDC rings in the polymer decreased, resulting in a gradual decrease in the adhesive properties of the PDC-based polyesters. Among all samples tested, P(PDC2) showed the highest adhesive strengths, with values of 15.26 MPa, 13.95 MPa, and 13.91 MPa on aluminum, iron, and copper plates, respectively. In contrast, P(PDC12), which contains the lowest proportion of PDC rings, showed significantly lower adhesive strengths of 2.53 MPa on aluminum, 0.77 MPa on iron, and 0.64 MPa on copper. Notably, all PDC-based polyesters demonstrated stronger adhesion to aluminum compared to iron and copper. For polymers from P(PDC3) to P(PDC6), adhesion to iron and copper gradually decreased with a decrease in the PDC content, whereas adhesion to aluminum remained relatively stable. A comparison of P(PDC6), P(PDC8), and P(PDC12) reveals a sharp decline in adhesion to iron and copper from P(PDC6) to P(PDC8). On the other hand, the adhesion to aluminum only dropped significantly at P(PDC12).

Observation of the fracture surfaces after the tensile lap-shear tests provided further insight into the adhesion mechanism. For P(PDC2), P(PDC3), P(PDC4), and P(PDC6), a mixed failure mode involving both adhesive failure at the polymer-metal interface and cohesive failure within the polymer was observed. In contrast, P(PDC8) and P(PDC12) exhibited purely adhesive failure, where the polymer cleanly detached from the metal surface (Supplementary Fig. S8). This suggests that as the alkylene chain lengthens and the PDC ring content decreases, the interaction between the polymer and the metal surface indeed weakens.

When compared to a commercial quick-drying metal adhesive containing cyanoacrylate as the active component, P(PDC2) outperformed the commercial product in adhesive to both aluminum and copper. For iron, the adhesive strength of P(PDC2) was slightly lower than that of the quick-drying metal adhesive, measuring 13.95 MPa and 14.36 MPa, respectively. However, from P(PDC2) to P(PDC6), the adhesive strengths of PDC-based polyesters on aluminum consistently exceeded that of the quick-drying metal adhesive. These results indicate that PDC polyesters have excellent adhesion to metal surfaces, with adhesive strengths increasing as the PDC content in the polymer increases.

Biodegradation Test

We very recently reported the biodegradation behaivor of P(PDC2) and P(PDC3), and their corresponding monomers, PDC and bishydroxyethyl-substituted PDC (BHPDC), in a simulated natural water35. In this study, we evaluated the biodegradability of the polyesters from P(PDC4) to P(PDC12) under the same conditions, following the ISO 14851:1999 standard (Fig. 6). For comparison, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) was tested as a negative control, and cellulose was included to confirm the biological activity of the soil inoculum.

In the biodegradation experiments conducted over ~60 days, P(PDC4) showed a similar biodegradation trend to P(PDC2) and P(PDC3), but its biodegradation rate was significantly lower, reaching only 33.6% compared to over 50% for P(PDC2) and P(PDC3). Notably, the biodegradation rate of PDC-based polyesters decreased abruptly from P(PDC6). It is evident that during the first 30 days of the biodegradation test, P(PDC6) to P(PDC12) showed very similar biodegradation behavior, with each degrading by only about 3%. Over the next 30 days, although their degradation rates began to diverge slightly, the overall biodegradation remained low. P(PDC6), which had the highest biodegradation rate among them, reached only 8.9% by the end of the test. In contrast, P(PDC12), which was the least biodegradable, showed no further change in decomposition rate after day 30, maintaining a rate of approximately 2.5%. Consistent with these quantitative results, visual observations after 60 days showed that P(PDC2), P(PDC3), and P(PDC4) had completely disintegrated, leaving no visible solid particles in the water. In contrast, P(PDC6), P(PDC8), and P(PDC12) remained as solid pieces, although they appeared swollen and their color had faded compared to their initial state (Supplementary Fig. S9). This abrupt decrease in the biodegradation rate from P(PDC4) to P(PDC6) is believed to result primarily from a sudden change in the properties of the PDC-based polyesters. Specifically, the polyesters synthesized in this study begin to exhibit crystallinity from P(PDC6) onward, and this increase in structural order is hypothesized to be the primary factor influencing their surface characteristics and, consequently, their interaction with microorganisms.

To investigate how the onset of crystallinity affects the polymer surface properties relevant to biodegradation, we measured the water contact angles of the polymer films. Due to the poor solubility of P(PDC8) and P(PDC12) in common solvents, measurements were limited to P(PDC2), P(PDC3), P(PDC4), and P(PDC6) (Fig. 7 and Table 1). The films of P(PDC2), P(PDC3), P(PDC4), and P(PDC6) displayed the water contact angles of 60°, 68°, 77°, and 104°, respectively. As the alkylene chain length increased, the water contact angle also increased, indicating greater hydrophobicity. Between P(PDC2) and P(PDC4), although the water contact angles increased, they remained below 90°, suggesting only a moderate change in hydrophobicity. However, a notable shift occurred between P(PDC4) and P(PDC6), with the water contact angle of P(PDC6) exceeding 90°, signifying a transition to a highly hydrophobic surface. This result suggests that the increased crystallinity in P(PDC6) leads to more ordered chain packing, which in turn makes the surface more hydrophobic. This increased hydrophobicity directly hinders microbial access and enzymatic activity, explaining the sharp decrease in biodegradation observed.

Furthermore, to assess whether the thermal treatment required for adhesion affects the polymer’s inherent biodegradability, a separate biodegradation test was conducted. The biodegradability of P(PDC2), P(PDC3), and P(PDC4) was compared before and after the adhesion treatment. For the preparation of heat-treated samples, polymer residues were scraped from the metal substrates after the adhesion process at 200 °C under vacuum and subsequently ground into powder with particle sizes smaller than 250 μm. Since the microbial environment (pond water and bottom soil) was sampled at a different time than in our main study (Fig. 6), control samples of the unheated polymers were also tested. The results indicated that, although the biodegradation rate of the post-adhesion polymers was reduced compared to their unheated counterparts, they retained a significant degree of biodegradability (Supplementary Fig. S10). This observation supports the hypothesis that the ring-opening and cross-linking reactions responsible for adhesion occur predominantly at the polymer-metal interface. Consequently, the bulk of the polymer material, which is not in direct contact with the metal, remains largely unaltered and preserves its biodegradable character. The observed decrease in overall biodegradability can thus be attributed to the presence of the less degradable, cross-linked interfacial layer.

Conclusion

A series of functional PDC-based polyesters were successfully synthesized by polymerizing PDC with diols containing alkylene chains of varying lengths. These polymers were found to exhibit two distinctly different sets of properties depending on the alkylene chain length. When the alkylene chains consisted of 2, 3, or 4 carbon atoms, i.e., P(PDC2), P(PDC3), and P(PDC4), respectively, the resulting PDC-based polyesters were amorphous powders without crystalline characteristics. All these polyesters exhibited well-defined biodegradability in simulated natural water systems, with degradation rates decreasing as the alkylene chain length increased.

In contrast, when the alkylene chain length was 6 carbons or more, i.e., P(PDC6), P(PDC8), and P(PDC12), the PDC-based polyesters exhibited crystallinity, demonstrated good mechanical properties, and showed minimal biodegradability. Notably, regardless of the alkylene chain length, all PDC-based polyesters showed adhesive properties to various metals. However, as the alkylene chain length increased, the PDC content in the polyester decreased, resulting in a corresponding decline in metal adhesion. Among the tested metals, the PDC-based polyesters showed the most excellent adhesion performance to aluminum, and their highest adhesive performance to various metals was comparable or exceeded that of a commercial quick-drying metal adhesive. These findings highlight the potential of PDC-based polyesters as safe, bio-based, and environmentally friendly alternatives for high-performance metal adhesives.

References

Vink, E. T., Rabago, K. R., Glassner, D. A. & Gruber, P. R. Applications of life cycle assessment to NatureWorks™ polylactide (PLA) production. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 80, 403–419 (2003).

Hirota, S. I., Sato, T., Tominaga, Y., Asai, S. & Sumita, M. The effect of high-pressure carbon dioxide treatment on the crystallization behavior and mechanical properties of poly (l-lactic acid)/poly (methyl methacrylate) blends. Polymer 47, 3954–3960 (2006).

Mekonnen, T., Mussone, P., Khalil, H. & Bressler, D. Progress in bio-based plastics and plasticizing modifications. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 13379–13398 (2013).

Garrison, T. F., Murawski, A. & Quirino, R. L. Bio-based polymers with potential for biodegradability. Polymers 8, 262 (2016).

Iwata, T. Biodegradable and bio-based polymers: future prospects of eco-friendly plastics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 3210–3215 (2015).

Zhang, Q. et al. Bio-based polyesters: recent progress and future prospects. Prog. Polym. Sci. 120, 101430 (2021).

Zeng, C., Seino, H., Ren, J., Hatanaka, K. & Yoshie, N. Bio-based furan polymers with self-healing ability. Macromolecules 46, 1794–1802 (2013).

Wang, J. et al. Highly degradable bio-based plastic with water-assisted shaping process and exceptional mechanical properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 347, 122773 (2024).

Yu, O. & Kim, K. H. Lignin to materials: a focused review on recent novel lignin applications. Appl. Sci. 10, 4626 (2019).

Kun, D. & Pukánszky, B. Polymer/lignin blends: Interactions, properties, applications. Eur. Polym. J. 93, 618–641 (2017).

Rinaldi, R. et al. Paving the way for lignin valorisation: recent advances in bioengineering, biorefining and catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 8164 (2016).

Chung, Y. L. et al. A renewable lignin–lactide copolymer and application in biobased composites. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 1, 1231–1238 (2013).

Rico-García, D. et al. Lignin-based hydrogels: synthesis and applications. Polymers 12, 81 (2020).

Ragauskas, A. J. et al. Lignin valorization: improving lignin processing in the biorefinery. Science 344, 1246843 (2014).

Shi, Y. et al. Lignin hydrogel sensor with anti-dehydration, anti-freezing, and reproducible adhesion prepared based on the room-temperature induction of zinc chloride-lignin redox system. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 279, 135493 (2024).

Mei, Q., Shen, X., Liu, H. & Han, B. Selectively transform lignin into value-added chemicals. Chin. Chem. Lett. 30, 15–24 (2019).

Li, C., Zhao, X., Wang, A., Huber, G. W. & Zhang, T. Catalytic transformation of lignin for the production of chemicals and fuels. Chem. Rev. 115, 11559–11624 (2015).

Mahmood, N., Yuan, Z., Schmidt, J. & Xu, C. C. Depolymerization of lignins and their applications for the preparation of polyols and rigid polyurethane foams: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 60, 317–329 (2016).

Schutyser, W. et al. Chemicals from lignin: an interplay of lignocellulose fractionation, depolymerisation, and upgrading. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 852–908 (2018).

Bugg, T. D., Ahmad, M., Hardiman, E. M. & Rahmanpour, R. Pathways for degradation of lignin in bacteria and fungi. Nat. Prod. Rep. 28, 1883–1896 (2011).

Otsuka, Y. et al. High-level production of 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid from a lignin-derived aromatic compound by metabolically engineered fermentation to realize industrial valorization processes of lignin. Bioresour. Technol. 377, 128956 (2023).

Jia, H. et al. Ion conductive organogels based on cellulose and lignin-derived metabolic intermediate. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 12, 501–511 (2024).

Shimura, T. et al. Improved thermal properties of polydimethylsiloxane by copolymerization and thiol-ene crosslinking of 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid moiety. Polym. Chem. 16, 45–51 (2025).

Cheng, Y. et al. Accelerated development of novel biomass-based polyurethane adhesives via machine learning. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 17, 15959–15968 (2025).

Michinobu, T. et al. Fusible, elastic, and biodegradable polyesters of 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid (PDC). Polym. J. 41, 1111–1116 (2009).

Michinobu, T. et al. Synthesis and characterization of hybrid biopolymers of L-lactic acid and 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid. J. Macromol. Sci. A 47, 564–570 (2010).

Shikinaka, K. et al. Thermoplastic polyesters of 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid (PDC) obtained from a metabolic intermediate of lignin. Sen’i Gakkaishi 69, 39–47 (2013).

Patel, M. R., Shukla, J. M., Patel, N. K. & Patel, K. H. Biomaterial based novel polyurethane adhesives for wood to wood and metal to metal bonding. Mater. Res. 12, 385–393 (2009).

Zhang, Y. et al. A high-performance bio-adhesive using hyperbranched aminated soybean polysaccharide and bio-based epoxide. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 7, 2000148 (2020).

Westerman, C. R., McGill, B. C. & Wilker, J. J. Sustainably sourced components to generate high-strength adhesives. Nature 621, 306–311 (2023).

Michinobu, T. et al. Click synthesis and adhesive properties of novel biomass-based polymers from lignin-derived stable metabolic intermediate. Polym. J. 43, 648–653 (2011).

Hishida, M. et al. Polyesters of 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid (PDC) as bio-based plastics exhibiting strong adhering properties. Polym. J. 41, 297–302 (2009).

Jin, Y. et al. Click synthesis of triazole polymers based on lignin-derived metabolic intermediate and their strong adhesive properties to Cu plate. Polymers 15, 1349 (2023).

Cheng, Y. et al. Polyurethanes based on lignin-derived metabolic intermediate with strong adhesion to metals. Polym., Chem. 13, 6589–6598 (2022).

Jin, Y. et al. Biodegradable and wood adhesive polyesters based on lignin-derived 2-pyrone-4, 6-dicarboxylic acid. RSC Sustain. 2, 1985–1993 (2024).

Kanno, H. A simple derivation of the empirical rule TGTM=23. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 44, 409–413 (1981).

Hasegawa, Y. et al. Tenacious epoxy adhesives prepared from lignin-derived stable metabolic intermediate. Sen’i Gakkaishi 65, 359–362 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by JST CREST, grant number JPMJCR23L4, JST the establishment of university fellowships towards the creation of science technology innovation, grant number JPMJFS2112, NEDO, grant number 23200050-0, JST SPRING, Grant Number JPMJSP2106, and the Fuji Seal Foundation. We thank the Core Facility Center, Institute of Science Tokyo, for the XRD measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M. conceived the concept of this work. Y.J. and K.Y. carried out experiments with the assistance of S.K. A.I. and K.K. contributed to experimental guidance. M.F., T.A., Y.S., Y.O., N.K., E.M., and M.N. provided the resources of this work. T.M., E.M., and Y.J. contributed to funding acquisition. Y.J. wrote the manuscript. T.M. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to finalizing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We confirm that all methods used in this work are performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, Y., Yoshida, K., Kimura, S. et al. Effects of alkylene spacer length of 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid polyesters on biodegradability and metal adhesive properties. NPG Asia Mater 17, 47 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-025-00626-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-025-00626-3