Abstract

Hydration of materials affects their antifouling properties, and polyethylene glycol (PEG) is highly hydrated and biocompatible. PEGylated dendrimers have been studied as drug carriers that passively accumulate in tumors owing to their enhanced permeability and retention effect. In this study, we synthesized various PEGylated dendrimers with different PEG molecular weights, bound numbers, and dendrimer generations, and analyzed their hydration properties using differential scanning calorimetry and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Intermediate water is defined as water molecules loosely bound to a material, the amount of which has been reported to be a useful index of bioinert properties. The amount of intermediate water was estimated from enthalpy change in melting peaks below 0 °C, considering a PEG-water eutectic system. Our results indicate that intermediate water was richer in PEGylated dendrimers with longer and more PEG chains. These PEGylated dendrimers, with longer and more PEG chains, also showed enhanced tumor accumulation after intravenous injection. The tumor-to-liver ratio correlated with the intermediate water content in the PEGylated dendrimers. This suggests that hydration is an important factor influencing dendrimer biodistribution, which is a possible criterion in designing nanocarriers for drug delivery systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drug delivery systems (DDSs) are useful for enhancing drug activity and reducing side effects. Biocompatible nanoparticles with prolonged blood circulation have been extensively studied as DDS nanocarriers for cancer chemotherapy, as they can effectively accumulate in tumors via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect1,2,3,4. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is a representative biocompatible polymer widely used for surface modification of DDS nanocarriers, such as liposomes, polymeric micelles, and dendrimers1,2,3,4,5,6. PEG length and density of PEGylated nanoparticles affected their biodistribution. Modification with longer PEG at higher densities prolongs blood circulation and improves tumor accumulation6,7. Therefore, it is necessary to optimize the structure of PEGylated nanoparticles for their DDS application.

As biomaterials work in water, their hydration properties affect their functions. Many researchers have studied the hydration of various biocompatible polymers, such as zwitterionic polymers and PEG8,9,10,11,12. An intermediate water concept has been proposed in which hydration and blood compatibility in polymer materials are related11,12. Based on this concept, hydrated water molecules are classified into non-freezing water, free water, and intermediate water, and are analyzed using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Non-freezing and free water interact strongly and scarcely with the materials. The former does not freeze even at −100 °C, and the latter melts at 0 °C. Intermediate water loosely interacts with materials whose melting peak appears below 0 °C in a DSC analysis. The intermediate water content in materials substantially affects their blood compatibility because the intermediate water layer at the surface suppresses nonspecific interactions11,12. Recently, we reported that intermediate water-rich zwitterionic polymer-conjugated dendrimers accumulated in tumors after intravenous injection, but intermediate water-poor zwitterionic monomer-conjugated dendrimer did not, suggesting that intermediate water content also affects the biodistribution of DDS materials13. Although numerous studies have focused on the PEG hydration properties, estimating the intermediate water content is difficult because a eutectic system exists in PEG/water mixtures14,15,16,17,18. In our previous work, PEGylated polyamidoamine (PAMAM) generation 4 (G4) dendrimers conjugated with PEG2k at high and low densities, PEG2k64G4 and PEG2k5G4, were synthesized, and their hydration states and tumor accumulation were examined. PEG2k64G4 exhibited a DSC profile similar to that of free PEG2k, whereas PEG2k5G4 exhibited a markedly different DSC profile. PEG2k64G4 accumulated in tumors, whereas PEG2k5G4 did not19. Although these results suggest that hydration may affect tumor accumulation, a systematic comparison is required to confirm this correlation. In addition, the intermediate water content could not be evaluated in previous studies because of the eutectic PEG/water system18.

Dendrimers are potent nanoparticles for DDS, with controllable size and terminal numbers20,21,22. Thus, dendrimers are useful as a nanoplatform to synthesize various PEGylated dendrimers with different structures for comparison. In this study, some series of PEGylated dendrimers with different PEG molecular weights (1k, 2k, and 5k) and PEG bound ratios (25%, 50% 75% and 100%) using different dendrimer generations (G3–G5) were synthesized (Fig. 1). Their hydration was analyzed using DSC and temperature-variable Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy. Intermediate water content was calculated from DSC results, considering the melting of PEG crystals. The binding of the PEGylated dendrimers to a serum protein and macrophages was examined. And, the biodistribution of PEGylated dendrimers was examined in tumor-bearing mice by in vivo and ex vivo fluorescence imaging. The relation between the hydration and biodistribution was investigated in our PEGylated dendrimers.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of PEGylated dendrimers

Various PEGylated dendrimers were synthesized using PAMAM dendrimers of G3–G5 and PEG of 1, 2, and 5 kDa at different binding ratios, as described in our previous report19. Briefly, methoxy PEG with different molecular weights was reacted with 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate to introduce a 4-nitrophenylcarbonate group at the end group. N6-((Benzyloxy)carbonyl)-N2-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-lysine (Boc-Lys(Z)) was conjugated to all terminal amines of the PAMAM dendrimers of different generations. After Boc group deprotection of the dendrimers, PEG-4-nitrophenylcarbonate with different molecular weights was reacted at different ratios to obtain various PEG-Lys(Z)-dendrimers (Table S1). Then, indocyanine green (ICG), a near-infrared fluorescent dye, was labeled at the lysine side chain of the PEGylated dendrimers after Z group deprotection for animal experiments (Table S1). Five equivalents of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) green-fluorescent dye were reacted with the PEGylated dendrimers instead of ICG for cell experiments23. Synthesized dendrimers were characterized by 1H NMR spectroscopy using an ECX-400 instrument (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The ICG-bound number was estimated based on absorbance at 800 nm (molar absorption coefficient of ICG: ε = 147,000), as shown in Table S1. The FITC-bound number was estimated to be 495 nm from a calibration curve23.

DSC measurements

Aqueous solutions (10 mg/mL) were prepared and incubated for 7 days. Approximately 5 mg of the hydrated sample was prepared in an aluminum container, the water content of which was adjusted after air drying. After sealing, the DSC curves were measured using a TA Instruments DSC250 RCS90 or Shimadzu TA60 instrument. The hydrated sample was heated under nitrogen to 80 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min, cooled to −80 °C at the same rate, and then reheated to 80 °C. Water content (WC) was calculated using the following formula (Eq. 1),

where the masses of the empty container, container containing the hydration sample, and container containing the hydration sample after water removal are W0, W1, and W2, respectively19. W2 was obtained from a perforated DSC sample after vacuum drying at 120 °C for 48 h. Intermediate water content (WIM) was calculated using Eq. 2, as described in a previous report11,24 with modifications.

where ΔHm1 and ΔHm2 were estimated as the enthalpy change per gram from the area of all melting peaks below 0 °C and the melting peak of PEG with 0% WC during the heating, respectively. When the melting peak exceeded 0 °C, free water was considered to have appeared.

FT-IR analysis

FT-IR spectra were measured using the BL43IR beamline (SPring-8, Hyogo, Japan). The experimental procedure was identical to that described in our previous report18. In brief, a dendrimer sample with 70% WC was sandwiched between two barium fluoride (BaF2) plates. Sample temperature was cooled from 80 to −80 °C, then heated from −80 to 80 °C at a 10 °C/min rate. Spectra were obtained every 30 s during the cooling and heating processes.

Calculation of R f/D

The PEG chain conformation was estimated using the ratio of the Flory radius (Rf) to the average chain spacing (D)6, and the Flory radius was calculated using Eq. 3, as follows:

where a is the monomer length, 0.35 nm, and N is the degree of polymerization of PEG, calculated as the molecular weight divided by 44. Average chain spacing was estimated using Eq. 4:

where A is the area occupied per PEG chain.

Protein-binding assay

A protein-binding assay was performed according to a previously reported method25. The PEGylated dendrimers were dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of 15 µM. The hydrodynamic diameters of PEGylated dendrimers were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis using nanoPartica (SZ-100V2, HORIBA Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) at 25 °C. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution was prepared using PBS at a concentration of 150 µM. The solutions of BSA and PEGylated dendrimers were mixed at final concentrations of 15 μM and 1.5 μM, respectively. After incubation for 30 min at 25 °C, hydrodynamic diameters were also measured by DLS.

Interaction of PEGylated dendrimers with macrophages

The interaction of the PEGylated dendrimers with RAW264 cells (RIKEN BRC) was investigated by flow cytometry according to our previous method23, with some modifications. RAW264 Cells (6 × 104 cells) were seeded in a 24-well plate and cultured for 2 days in minimum essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). FITC-labeled PEGylated dendrimers were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C in the culture medium at a final FITC concentration of 5 µM. A PAMAM G4 dendrimer modified with 1,2-cyclohexanedicarboxylic acid and phenylalanine, G4-CHex-Phe, was used as a positive control23. Following treatment with 0.25% trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid solution, the cells were suspended in PBS. After washing with PBS, 1 × 104 cells were analyzed using a FACS Melody cell sorter (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) to measure the mean fluorescence intensity.

In vivo and ex vivo imaging

4T1 cells were purchased from ATCC and maintained using DMEM containing 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin mixture at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. 4T1 cells (5 × 105 cells) were dispersed in PBS (100 µL) and subcutaneously injected into BALB/C mice. After 2 weeks, the ICG-labeled dendrimer solution (18 nmol ICG/mL, 0.1 mL) was injected intravenously into tumor-bearing mice. After 3–24 h, the mice were anesthetized and imaged in vivo using IVIS Lumina Series III (PerkinElmer, Inc., Shelton, CT, USA). After 24 h, the mice were euthanized, and the tumors, liver, kidney, lung, heart, and spleen were harvested for ex vivo imaging.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of various PEGylated dendrimers with different structures

Previously, fully PEGylated dendrimers with lysine linkers were synthesized using PEG (2k and 5k) and PAMAM dendrimers (G4 and G5) for in vivo imaging and biodistribution analysis26. Partially PEGylated dendrimers of PEG2k and G4 were also synthesized by changing reaction ratios19. In this study, PEGylated PAMAM dendrimers of different generations (G3–G5), PEG molecular weights (1k, 2k, and 5k), and numbers of bound PEG chains were synthesized using the same method, by changing the reaction ratios (Table S1). The synthesized dendrimers were characterized using 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figs. S1–S10). The bound number of PEG molecules was calculated from the integral ratio of the peak at 3.2 ppm, derived from the PEG methoxy group, to the dendrimer peaks at 2.2–2.6 ppm. Various PEGylated dendrimers with different PEG lengths and bound numbers were synthesized, as shown in Table 1. A comparison of the fully PEGylated G4 dendrimers with PEG1k, 2k, and 5k was useful for considering the influence of PEG length. PEGylated G4 dendrimers with PEG2k and 5k at different bound numbers were used to compare the PEG-bound numbers. The molecular weight is closely related to the hydrodynamic size, which largely influences blood circulation in vivo1,2,3,4,5,6,22. PEG1k128G5, PEG2k64G4, and PEG5k32G3 have similar molecular weights, but their PEG lengths and bound numbers are different. A comparison of these dendrimers is useful for investigating the effects of the PEG length and PEG-bound number, excluding the molecular weight effect. The smallest PEGylated dendrimer is PEG2k15G4 in this study, with a molecular weight of 48 kDa. This was larger than the possible threshold (40 kDa) for renal clearance22,27. Thus, all dendrimers in this study were retained after injection into the animals. For the animal experiments, ICG was conjugated to the amino group in the side chain of lysine in these dendrimers. From one to five ICG molecules were bound to the PEGylated dendrimers, which were listed in Table S1. The PEG density at the surface of the dendrimers may affect hydration and biodistribution. The Rf/D ratio, an index of PEG density, was calculated using the core dendrimer diameter and bound PEG number, which are also listed in Table 1. PEG conformations are classified as mushrooms or brushes when the Rf/D ratio is smaller or larger than one, respectively6. Our calculations indicated that a PEG brush was formed on the surface of all the dendrimers. The Rf/D ratio increased when the PEG length and bound number increased, suggesting that the PEG density increased by increasing PEG length and bound numbers.

Hydration analysis of various PEGylated dendrimers

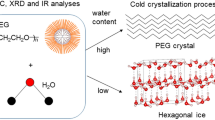

The synthesized PEGylated dendrimers and PEG were hydrated, and the hydration was analyzed using samples with different water contents. PEG2k and PEG2k64G4 were analyzed by DSC, XRD, and FT-IR spectroscopy as described in our previous report18, as shown in Figs. S11 and S12. During the heating process in DSC, the melting peak of PEG2k appeared near 40 °C, corresponding to the PEG crystal at low water content, and the melting peak gradually shifted to a lower temperature with increasing water content. At 20% WC, the melting peak appeared near −15 °C, and the crystallization peak appeared near −50 °C, which were considered to be the melting and crystallization peaks of the intermediate water. At a water content of 67%, two melting peaks were observed, corresponding to the PEG crystals and ice. The right edge of the melting peak reached 0 °C, indicating that intermediate water reached its maximum under these conditions (Fig. S11A). Temperature-dependent FT-IR spectroscopy of PEG2k was performed at 70% WC18. The PEG region showed spectral shifts from −30 to −15 °C during the heating process, while the water region changed between −30 and −5 °C. These indicate that the melting peaks at −20 and 0 °C in the DSC are derived from both PEG crystallites and ice, which are difficult to separate (Fig. S12). DSC data of PEG2k64G4 showed similar results to those of PEG2k (Fig. S12), although apparent signals were not observed below 0 °C with low water content (Fig. S11B).

The DSC curves of PEG1k and 5k and the other PEGylated dendrimers with different water contents during the heating process are shown in Fig. 2. DSC patterns observed for PEG1k and PEG5k (Fig. 2A, B) were similar to those of PEG2k (Fig. S11A). With a water content of around 70%, the right edge of the two melting peaks reached 0 °C, indicating that the intermediate water became the maximum under the condition. Temperature-dependent FT-IR spectroscopy of PEG1k and 5k was performed at 70% WC (Fig. S13A, B), which showed spectra similar to that of PEG2k (Fig. S12). DSC data of PEG1k64G4, PEG1k128G5, and PEG2k15G4 showed a single melting peak below 0 °C with water content of around 70% during the heating process (Fig. 2C–E), unlike PEG1k and PEG2k by themselves. This indicated that PEG crystals were not formed on the dendrimer surface in PEG1k64G4, PEG1k128G5, and PEG2k15G4 due to their short chains and low densities. Temperature-dependent FT-IR spectroscopy of these dendrimers was also carried out at 70% WC (Fig. S13C–E), indicating no signals derived from the PEG crystal. This suggests that long chains and high densities are necessary for PEG crystal formation on dendrimer surfaces. Because no signals derived from the PEG crystal were observed in these cases, the maximum amount of intermediate water can be estimated as 21%, 26%, and 24% for PEG1k64G4, PEG1k128G5, and PEG2k15G4, respectively, from the melting peak below 0 °C, based on the previous report11,24.

Figure 2 shows that other PEGylated dendrimers showed two melting peaks corresponding to PEG crystal and ice below 0°C. The right edge of the melting peak reached 0 °C at 70% WC. Both water and PEG signals were changed simultaneously in the temperature-dependent FT-IR spectra of PEG2k and PEG2k64G4 with 70% WC (Fig. S12). This suggests that the intermediate water content cannot be directly estimated from the DSC results, because a eutectic mixture of PEG and water is formed18. Thus, the intermediate water content was calculated by subtracting the PEG crystal signal from the total PEG crystal and ice signals. A linear relationship exists between PEG melting peak and its content, as shown in the following equation:

where ΔHPEG and ΔHPEG0% are the change in enthalpies per gram of PEG melting for the target water content and 0% WC, respectively. The measured and calculated melting peak areas of the PEG and PEGylated dendrimers are listed in Table S2. This calculation is valid because the measured and calculated values are almost consistent. Thus, the intermediate water content in all PEGylated dendrimers was calculated by subtracting the PEG contribution from the total melting peaks below 0 °C at around 70% WC. The measured values for PEG2k34G4 and PEG2k44G4 were significantly different from the calculated values. The calculated intermediate water content may be inappropriate. These dendrimers showed a phase separation (Fig. S14), which may have influenced PEG melting behavior. PEG is known to exhibit phase separation at high concentration28,29. The phase separation possibly affected the DSC curve, which was another factor to be considered.

The calculated maximum intermediate water contents of each PEGylated dendrimer are listed in Table 1. Intermediate water content increased with increasing PEG chain lengths in the PEGylated dendrimers of G4. PEGylated dendrimers of G4 with more PEG5k chains contained more intermediate water molecules, consistent with our previous reports19. These results indicated that dendrimers with longer and more PEG chains were highly hydrated. The fully PEGylated dendrimer, PEG5k32G3, contained more intermediate water molecules than the partially PEGylated dendrimer, PEG5k32G4, although the PEG chain length and bound number were the same. The Rf/D ratio is related to the intermediate water content. The apparent correlation between the Rf/D ratio and intermediate water content implies that denser PEG packing enhances the hydration state. Water molecules may be confined within the densely packed PEG brush layer at the periphery of the dendrimer owing to hydrogen bonding. These suggest that PEG density at the dendrimer surface also affects hydration. Their amounts in intermediate water of PEG1k128G5, PEG2k64G4, and PEG5k32G3 with similar molecular weights were different. Dendrimers with longer PEG chains contained more intermediate water molecules. This suggests that the intermediate water content is substantially affected by PEG length.

In PEGylated dendrimers, water molecules associate not only with the ether oxygen of the PEG units but also with the amide and tertiary amino groups of the PAMAM dendrimer core. Although DSC measurements provide information on the hydration state of the entire PEGylated dendrimer, hydration of the outermost surface is critical for mediating biological interactions. The maximum intermediate water contents of both PEG alone and the unmodified PAMAM dendrimer were examined as controls (Table S3). The core PAMAM dendrimer had 23% intermediate water at 58% WC, and PEG alone had more intermediate water than all PEGylated dendrimers. Some PEGylated dendrimers with short and fewer PEG chains have similar amounts of intermediate water to the PAMAM dendrimer without PEG, suggesting that the PEG coating on the surface of these dendrimers does not work well. Previously, FT-IR analysis of poly(2-methoxyethyl acrylate) films showed that the carbonyl group was hydrated before the hydration of the ether oxygen30. It is possible that the core dendrimer is hydrated in advance. Further investigations are required to elucidate the hydration structure of PEGylated dendrimers.

Interaction of PEGylated dendrimers with a serum protein and macrophages

We examined the binding of the PEGylated dendrimers to a serum protein, BSA, and their interactions with macrophages. DLS measurements were performed to estimate the size of the PEGylated dendrimers in the absence and presence of BSA (Fig. 3). The sizes of BSA alone and the dendrimer alone were less than or approximately 10 nm, respectively (Figs. 3 and S15). Our results revealed that the diameter of the non-PEGylated G4 dendrimer increased drastically from 4 to 220 nm after the addition of BSA, suggesting the formation of a protein corona. Similarly, the PEG1k-modified dendrimers also showed a pronounced size increase. This indicates that the dendrimer surface is insufficiently covered with short PEG molecules to induce protein corona formation. In contrast, the diameters of the PEG2k- and PEG5k-modified dendrimers remained almost unchanged in the presence of BSA. However, the size of PEG2k15G4 increased slightly after the addition of BSA. These indicate the effective suppression of protein corona formation due to longer PEG chains and higher PEG densities at the dendrimer periphery, which are consistent with previous reports25.

The association between the PEGylated dendrimers and macrophages was evaluated by flow cytometry. PEG1k64G4, PEG2k64G4, and PEG5k64G4 were labeled with 8, 2, and 8 FITC molecules, respectively. Then, macrophage-like RAW264 cells were incubated with these dendrimers for 3 h. All PEGylated dendrimers exhibited lower levels of cell association than the positive control hydrophobic G4-CHex-Phe (Fig. S16), although the PEG1k-modified dendrimer bound to BSA. The protein corona formed on nanoparticles possibly contains both opsonins and de-opsonins, which promote and inhibit macrophage uptake, respectively31. The proteins adsorbed onto the PEG1k-modified dendrimers possibly play a role in modulating their interactions with macrophages. Further detailed investigations are required to clarify the protein components adsorbed on PEGylated dendrimers.

Biodistribution of various PEGylated dendrimers

We investigated the biodistribution of each PEGylated dendrimer after intravenous injection using in vivo fluorescence imaging after 3–24 h (Fig. 4). Compared to the fully PEGylated G4 dendrimers with PEG1k, 2k, and 5k, the longer PEG-bearing dendrimers accumulated in the tumor more efficiently and rapidly. Compared with the PEGylated G4 dendrimers with PEG2k and 5k at different bound numbers, more PEG-grafted dendrimers accumulated in the tumor more efficiently and rapidly. Similar to the hydration properties, PEG1k128G5, PEG2k64G4, and PEG5k32G3, with similar molecular weights, showed different tumor accumulation properties. PEG2k64G4 and PEG5k32G3 accumulated in the tumor, whereas PEG1k128G5 did not.

Ex vivo imaging was performed after 24 h. Figure 5 shows the fluorescence signals of the tumor, liver, spleen, heart, lung, and kidney. Tumor accumulation reflects prolonged blood circulation due to the EPR effect. Accumulation in the lungs and heart was analyzed to assess the potential risk of off-target toxicity, and accumulation in the kidneys was examined to determine renal clearance. Accumulation in the liver and spleen results from foreign body reactions. Similar to in vivo imaging, PEGylated dendrimers with longer and more PEG chains showed improved tumor accumulation, indicating that PEG length and density are key factors for tumor accumulation. When the total molecular weight was the same, dendrimers with longer PEG chains accumulated in the tumor, whereas those with PEG1k did not. In previous reports, PEG2k-modified nanoparticles exhibited better in vivo circulation than shorter PEG-modified nanoparticles, and PEGylated nanoparticles with approximately 10% or more modifications were recommended to optimize nanoparticle pharmacokinetics6,7,22. These results are consistent with those of previous studies reporting that increasing the PEG chain length and grafting density enhances tumor accumulation. Therefore, our findings support the notion that the PEG parameters play a critical role in governing the biodistribution and tumor selectivity of PEGylated dendrimers.

Relation between hydration and biodistribution in PEGylated dendrimers

Finally, the relation between hydration and biodistribution was investigated. The tumor-to-liver ratio is often used as a tumor activity indicator, which is related to blood circulation in our system32. Thus, the intermediate water content and tumor-to-liver ratio in each PEGylated dendrimer were used as hydration and blood circulation indicators, respectively. Figure 6 shows a scatterplot of these parameters for each PEGylated dendrimer. A good correlation was observed between the maximum intermediate water content and tumor-to-liver ratio. As the maximum intermediate water content increased, the tumor-to-liver ratio tended to increase in the PEGylated dendrimers. Previous reports indicated that molecular weight is a possible factor in biodistribution22,27. Our results indicated that PEGylated dendrimers with similar molecular weights, PEG1k128G5, PEG2k64G4, and PEG5k32G3, had different intermediate water contents and showed different tumor accumulations (Table 1 and Fig. 4). This indicates that hydration is more important than molecular weight for determining biodistribution. Our previous report indicated similar trends, in which intermediate water-rich zwitterionic polymer-conjugated dendrimers accumulated in tumors more efficiently than an intermediate water-poor zwitterionic monomer-conjugated dendrimer13. Our results suggest that the hydration of drug carriers is an important factor in determining their fate after intravenous injection. Animal experiments are necessary to investigate the biodistribution. Reducing animal experiments is desirable for both animal welfare and R&D efficiency. Drug carrier pre-screening based on their hydration properties can reduce the number of animal experiments, which is useful for DDS nanocarrier development.

Figure 6 also shows that the tumor-to-liver ratios of our PEGylated dendrimers were smaller than two, indicating that these dendrimers accumulated in the liver as well as in the tumor. Previous studies reported that the charge, molecular weight, and architecture of polymers affect their biodistribution. High-molecular-weight polymers are more prone to hepatic accumulation despite their stealth properties. In addition, hydrophobic or charged polymers are cleared more readily than hydrophilic or neutral polymers, thereby accelerating hepatic clearance27, suggesting that biodistribution is not determined solely by the hydration state but is also influenced by other factors such as charge, molecular weight, and molecular architecture. The influence of multiple parameters on the biodistribution remains to be investigated to better understand and control the biodistribution of nanoparticles.

Conclusions

In this study, various PEGylated dendrimers were synthesized using different PEG molecular weights of 1k, 2k, and 5k, and dendrimer generations G3–G5 at different bound numbers. Their hydration was analyzed using DSC and temperature-dependent FT-IR spectroscopy. Due to the eutectic PEG and water mixtures, ice melting enthalpy was calculated by subtracting the PEG crystal melting enthalpy from the total melting enthalpy below 0°C. Comparing the intermediate water content among the PEGylated dendrimers, the maximum intermediate water content increased as the PEG length and bound numbers increased. Based on the calculated Rf/D ratios of the PEGylated dendrimers, PEG formed a brush structure at the dendrimer periphery. A higher brush density was strongly associated with an increased intermediate water content. Although some PEGylated dendrimers with shorter and fewer PEG chains interacted with BSA, the PEGylated dendrimers used in this study were not well recognized by macrophages. Biodistribution was also examined by injecting these PEGylated dendrimers into tumor-bearing mice. Dendrimers with longer PEG chains showed efficient tumor accumulation. Notably, a positive correlation was found between the maximum intermediate water content and tumor-to-liver ratio. Our results indicate that the intermediate water content is an important factor in determining biodistribution, especially blood circulation properties. This finding provides a novel conceptual framework for controlling biodistribution. Because other nanoparticle parameters, such as charge and molecular architecture, may affect their biodistribution, a comprehensive analysis is necessary to provide new design guidelines for DDS materials.

References

Maruyama, K. Intracellular targeting delivery of liposomal drugs to solid tumors based on EPR effects. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 63, 161–169 (2011).

Wicki, A., Witzigmann, D., Balasubramanian, V. & Huwyler, J. Nanomedicine in cancer therapy: challenges, opportunities, and clinical applications. J. Control. Release 200, 138–157 (2015).

Beach, M. A. et al. Polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery. Chem. Rev. 124, 5505–5616 (2024).

Fang, J., Nakamura, H. & Maeda, H. The EPR effect: unique features of tumor blood vessels for drug delivery, factors involved, and limitations and augmentation of the effect. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 63, 136–151 (2011).

Mishra, P., Nayak, B. & Dey, R. K. PEGylation in anti-cancer therapy: an overview. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 11, 337–348 (2016).

Suk, J. S., Xu, Q., Kim, N., Hanes, J. & Ensign, L. M. PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 99, 28–51 (2016).

Yang, Q. et al. Evading immune cell uptake and clearance requires PEG grafting at densities substantially exceeding the minimum for brush conformation. Mol. Pharm. 11, 1250–1258 (2014).

Li, Q. et al. Zwitterionic biomaterials. Chem. Rev. 122, 17073–17154 (2022).

Bag, M. A. & Valenzuela, L. M. Impact of the hydration states of polymers on their hemocompatibility for medical applications: a review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 1422 (2017).

Chen, S., Li, L., Zhao, C. & Zheng, J. Surface hydration: principles and applications toward low-fouling/nonfouling biomaterials. Polymer 51, 5283–5293 (2010).

Tanaka, M., Hayashi, T. & Morita, S. The roles of water molecules at the biointerface of medical polymers. Polym. J. 45, 701–710 (2013).

Tanaka, M., Morita, S. & Hayashi, T. Role of interfacial water in determining the interactions of proteins and cells with hydrated materials. Colloids Surf. B 198, 111449 (2021).

Kojima, C. et al. Hydration and biodistribution of zwitterionic dendrimers conjugating a sulfobetaine monomer and polymers. Langmuir 41, 1411–1417 (2025).

Hatakeyama, T., Kasuga, H., Tanaka, M. & Hatakeyama, H. Cold crystallization of poly(ethylene glycol)–water systems. Thermochim. Acta 465, 59–66 (2007).

Huang, L. & Nishinari, K. Interaction between poly(ethylene glycol) and water as studied by differential scanning calorimetry. J. Polym. Sci. B 39, 496–506 (2001).

Kuttich, B., Matt, A., Appel, C. & Stühn, B. X-ray scattering study on the crystalline and semi-crystalline structure of water/PEG mixtures in their eutectic phase diagram. Soft Matter 16, 10260–10267 (2020).

Gemmei-Ide, M., Motonaga, T., Kasai, R. & Kitano, H. Two-step recrystallization of water in concentrated aqueous solution of poly(ethylene glycol). J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 2188–2194 (2013).

Kojima, C., Suzuki, Y., Ikemoto, Y., Tanaka, M. & Matsumoto, A. Comparative study of PEG and PEGylated dendrimers in their eutectic mixtures with water analyzed using X-ray diffraction and infrared spectroscopy. Polym. J. 55, 63–73 (2023).

Tsujimoto, A. et al. Different hydration states and passive tumor targeting ability of polyethylene glycol-modified dendrimers with high and low PEG density. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 126, 112159 (2021).

Tomalia, D. A. Dendrimers, dendrons, and the dendritic state: Reflection on the last decade with expected new roles in pharma, medicine, and the life sciences. Pharmaceutics 16, 1530 (2024).

Svenson, S. & Tomalia, D. A. Dendrimers in biomedical applications—reflections on the field. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 57, 2106–2129 (2005).

Kaminskas, L. M., Boyd, B. J. & Porter, C. J. H. Dendrimer pharmacokinetics: the effect of size, structure and surface characteristics on ADME properties. Nanomedicine 6, 1063–1084 (2011).

Shiba, H. et al. Carbox-terminal dendrimers with phenylalanine for a pH-sensitive delivery system into immune cells including T cells. J. Mater. Chem. B 10, 2463–2470 (2022).

Sonoda, T., Kobayashi, S., Herai, K. & Tanaka, M. Side-chain spacing control of derivatives of poly(2-methoxyethyl acrylate): impact on hydration states and antithrombogenicity. Macromolecules 53, 8570–8580 (2020).

Ruggeri, F. et al. The dendrimer impact on vesicles can be tuned based on the lipid bilayer charge and the presence of albumin. Soft Matter 9, 8862–8870 (2013).

Kojima, C., Regino, C., Umeda, Y., Kobayashi, H. & Kono, K. Influence of dendrimer generation and polyethylene glycol length on the biodistribution of PEGylated dendrimers. Int. J. Pharm. 383, 293–296 (2010).

Fox, M. E., Szoka, F. C. & Fréchet, J. M. J. Soluble polymer carriers for the treatment of cancer: the importance of molecular architecture. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 1141–1151 (2009).

Annunziata, O. et al. Effect of polyethylene glycol on the liquid–liquid phase transition in aqueous protein solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14165–14170 (2002).

Derkaoui, N., Said, S., Grohens, Y., Olier, R. & Privat, M. PEG400 novel phase description in water. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 305, 330–338 (2007).

Morita, S., Tanaka, M. & Ozaki, Y. Time-resolved in situ ATR-IR observations of the process of sorption of water into a poly(2-methoxyethyl acrylate) film. Langmuir 23, 3750–3761 (2007).

Li, H. et al. The protein corona and its effects on nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems. Acta Biomater. 129, 57–72 (2021).

Hofheinz, F. et al. An investigation of the relation between tumor-to-liver ratio (TLR) and tumor-to-blood standard uptake ratio (SUR) in oncological FDG PET. EJNMMI Res. 6, 19 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Takashi Inui (Osaka Metropolitan University) for his help in animal experiments. The authors acknowledge the support from the Takeda Science Foundation for the use of the IVIS imaging system. The authors also thank the Open Research Facilities for Life Science and Technology, Institute of Science Tokyo, for DSC and flow cytometric analyses. The authors thank Professor Yoshitaka Kitamoto (Institute of Science Tokyo) and Ms. Atsumi Sakaguchi (Institute of Science Tokyo) for their help with the DLS and flow cytometric analyses, respectively. The authors also thank Professor Masaru Tanaka (Kyushu University) for his valuable discussions and insightful comments that greatly contributed to this work. This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) Grants JP22H04556 and JP19H05717 (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas: Aquatic Functional Materials), and JP24K01558 [Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B)].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.K. conceived the concept of this work. H.H., J.Y., and A.T. performed dendrimer synthesis. H.H., A.T., and C.K. evaluated the hydration properties of the materials. A.K. and J.Y. performed the in vitro and in vivo evaluation, respectively. H.H. wrote the original draft. Y.I. and C.K. contributed to experimental guidance, funding acquisition, and review and editing of the manuscript. A.M. contributed to supervision. All authors contributed to finalizing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The experimental protocol using mice was reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Osaka Metropolitan University (approval number: 23-26). Since no human participants were involved in this study, informed consent for participation was not included.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, H., Yao, J., Kubo, A. et al. Tumor accumulation in polyethylene glycol-modified dendrimers with enhanced hydration. NPG Asia Mater 17, 46 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-025-00628-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-025-00628-1