Abstract

Skyrmion-hosting cubic B20 alloys are considered a fruitful platform for various spintronic applications due to their pronounced tunability. However, disorder can limit their usability by pinning skyrmions and scattering magnons. Here, we probe the spin dynamics in the field-polarized phase of the skyrmion host Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge using spin wave small-angle neutron scattering (SWSANS). Unlike for typical B20 helimagnets, the corresponding SWSANS data do not possess a crucial cut-off feature but rather show smooth diffuse patterns. Our analytical calculations within the minimal model of a disordered cubic helimagnet reveal unusually strong damping of long-wavelength magnons in contrast with standard collinear spin structures. X-ray circular magnetic dichroism (XMCD) measurements indicate antiferromagnetic coupling between Cr and Mn ions, thus strongly supporting the considered model. Therefore, both experimental and theoretical evidence of the absence of well-defined helimagnon excitations in this material are provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Noncentrosymmetric magnets with Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction (DMI)1,2 are a subject of extensive studies nowadays. They host a family of noncollinear spin textures, including planar and conical helicoids, chiral soliton lattices, isolated skyrmions and skyrmion lattices, merons, hopfions, etc.3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 Importantly, complex non-coplanar magnetic structures, e.g., skyrmions, give rise to nontrivial transport phenomena such as the topological Hall effect15,16. From a practical point of view, promising applications of exotic spin structures in memory devices17,18 and unconventional computing19,20,21,22 are actively discussed. Particularly, periodic patterns of magnetic spirals and skyrmion crystals in chiral magnets are considered as media for magnonic applications23,24,25,26.

Cubic B20 alloys, e.g., Fe1-xCox Si and Mn1-xFex Ge, allow the fine-tuning of their electronic and magnetic properties when \(x\) is varied. For instance, it was shown that the spiral pitch essentially depends on \(x\), and the chirality can be switched at some \({x}_{c}\)27,28. Moreover, types and properties of topological textures, including their stability, can be tuned by varying \(x\) and dopants29,30. Microscopically, this behavior can be connected with the exchange interaction and DMI variation resulting from the electronic band structure modification with x 31. However, in some cases, even relatively small dopant concentrations lead to crucial changes in magnetic properties. In particular, Mn1-xFex Si exhibits only short-range magnetic order at \(x > 0.11\), which eventually disappears at \(x > 0.17\)32,33,34,35. This property can limit possible practical applications of these materials.

The phase diagram of typical B20 helimagnets (e.g., MnSi) is quite simple: it consists of helical, conical, field-polarized phases and includes a pocket of skyrmion lattice A-phase near the ordering temperature8. While the magnetic moments are all aligned with the external magnetic field in the field-polarized phase, this regime is far from trivial. It hosts magnons with a nonreciprocal spectrum36

where \(A\) is the spin-wave stiffness, \({{\bf{k}}}_{s}\) is the spiral vector oriented along the external magnetic field \({\bf{h}}=g{\mu }_{B}{\bf{H}}\) measured in energy units, and \({h}_{C2}=A{k}_{s}^{2}\) is the field of the transition between conical and field-polarized phase (see, e.g., Ref. 37). This dispersion law leads, for instance, to the magnetochiral effect for phonons38,39, i.e., a difference in the propagation speed for left and right transverse acoustic phonons.

In the last decade, small-angle inelastic neutron scattering on spin waves with dispersion given by Eq. (1) (henceforth referred to as SWSANS—spin wave small-angle neutron scattering) was established to be a relatively simple yet quantitatively accurate technique to probe magnon dynamics. It allows extracting the spin-wave stiffness and magnon damping parameters40,41. For well-defined magnons, the SWSANS scattering maps roughly correspond to the sum of two circles with the crucial cut-off feature beyond which the signal drastically drops down. The cut-off angle was used for the characterization of B20 helimagnets MnSi40 and Cu2OSeO342 as well as for the more complex Co8Zn8Mn4 cubic alloy41. Noteworthy, in ref. 41, it was shown that the magnon damping drastically enhances when the temperature is close to the one of transition to the disordered spin-glass phase43.

In our study, we show that the chiral B20 system Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge, despite being a conventional Bak-Jensen cubic helimagnet5 according to its phase diagram44,45, does not possess well-defined magnon excitations in the field-polarized regime. Our SWSANS maps do not reveal any cut-off features characteristic to the earlier studied compounds. For theoretical calculations, we use the model of a cubic helimagnet with a bond disorder, which is strongly supported by our X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) measurements showing antiferromagnetic coupling between Cr and Mn ions. Our model hints at the possibility of low-energy magnon localization and strong damping of moderate-wavelength magnons, which drastically contrasts with usual collinear magnetic systems. Thus, the remarkable tunability of mixed B20 alloy properties can have an important drawback from the spin dynamics point of view, limiting their prospective applications.

Materials and methods

Sample synthesis

Polycrystalline Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge was synthesized using the arc-melting technique, followed by annealing according to the procedure outlined in Ref. 46. Details of the sample preparation are given in Ref. 45. The same sample as in the previous elastic SANS study was used.

Neutron scattering

Small-angle neutron scattering measurements were conducted using the SANS-I instrument at the Paul Scherrer Institut (PSI). Neutrons with wavelength \(\lambda =6\) Å (\({k}_{i}\approx 10.5\) nm-1) were used. The instrument configuration included both collimation and sample-detector distances of 6 m. Magnetic field was controlled using a 6.8 T horizontal-field cryomagnet (MA7). Background SWSANS signal was measured at the base temperature of 2 K and the magnetic field of 3 T where the spin-wave contribution is suppressed. The corresponding SANS pattern was subsequently subtracted from all the other SWSANS datasets. It allows us to get rid of the diffuse elastic contribution due to impurity scattering (see, e.g., refs. 47,48). Importantly, the resulting SWSANS maps have a signal centered at \(\pm {{\bf{k}}}_{s}\). The typical acquisition time for each pattern was 2 hours. The analysis of all SANS data was performed using the GRASP software49.

X-ray magnetic circular dichroism

X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) measurements were conducted using the VEKMAG instrument at BESSY-II in Berlin, Germany50. A polycrystalline ingot of Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge was cleaved in vacuum to prevent surface oxidation. The XMCD measurements were performed in total electron yield (TEY) detection mode, utilizing 77% circularly polarized (\({C}^{+}\)) soft X-rays at the Cr and Mn \({L}_{2,3}\) edges. Magnetic fields ranging from \(-0.2\) T to \(+0.2\) T were applied parallel to the x-ray beam.

Results

Spin wave small-angle neutron scattering

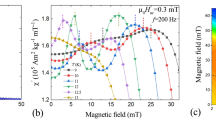

According to the previous studies44,45,46 Cr0.82Mn0.18 Ge is characterized by a magnetic ordering temperature \({T}_{C}\approx 13\) K (Fig. 1a), and a ground state which exhibits a spiral pitch \(L\) which varies from \(\approx 40\) nm close to \({T}_{C}\) to \(\approx 35\) nm at \(T=2\) K, for which the critical field \({\mu }_{0}{H}_{C2}\approx 60\) mT. Then, using the low-temperature values of the helical (conical) wavevector \({k}_{s}\approx 0.18\) nm-1) (Fig. 1b and 1c) and \(g{\mu }_{B}{H}_{C2}=A{k}_{s}^{2}\), we arrive at the estimation \(A\approx 22\) meV Å2. Taking the lattice parameter \(a\approx 4.8\) Å, we can estimate \({T}_{C}\) as \(A{a}^{2}\), yielding a reasonable value of \(\approx 11\) K. Also, accounting for the similarity of the phase diagram (Fig. 1a) with that of prototypical B20 helimagnet MnSi8, we conclude that from the macroscopic view, Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge is a typical representative of its class.

a Magnetic phase diagram of Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge constructed from ac-susceptibility measurements reproduced from ref. 45. SANS patterns measured in (b) helical state after zero-field cooling and (c) conical state at 2 K.

However, the crucial observation of ref. 45 is related to the helicoid structures’ correlation length, which was shown to be \(\sim 100\) nm at relatively low temperatures. It is an apparent manifestation of the short-range magnetic order since the correlation length is only several times larger than the spiral pitch. Moreover, at the same time, it is much smaller than the grain size of the polycrystalline sample d ~ 1 μm. Here, the situation resembles recent studies on the Mn1-xFexSi B20 alloy, where for \(x > 0.1\) SANS reveals a finite correlation length for the helicoids35, which was associated with strong bond disorder in the form of antiferromagnetic bonds. Remarkably, that observation lies in good agreement with other studies indicating a short-range order phase at these concentrations (see Refs. 32,33,34).

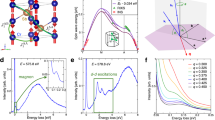

We proceed with SWSANS studies of Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge at magnetic fields \(H > {H}_{C2}\approx 60\) mT. Typical SWSANS maps in the field-polarized state of Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge are shown in Fig. 2a-e. The typical acquisition time for each pattern was 2 h. For well-defined magnons with the spectrum described by Eq. (1), one can expect circle-shaped signals with the cut-off corresponding to \(q\sim {\theta }_{0}{k}_{i}\), where \({\theta }_{0}={\hslash }^{2}/2{m}_{n}A\sim 0.1\) is estimated for Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge (see Fig. 2f,g). However, at all measurement temperatures from 2 K to 12 K, we observed only weak diffuse scattering without any cut-off feature (Fig. 2a-e). A similar result was reported for Co8Zn8Mn4 in the vicinity of the low-temperature spin-glass phase41.

Magnetic field dependence of SWSANS patterns measured at 8 K: a \({\mu }_{0}H=80\) mT, b 100 mT, c 120 mT and d 140 mT. e Radial profiles of SWSANS intensity averaged from the spiral Bragg angle measured at \({\mu }_{0}H=80\) mT at different temperatures. f Calculated SWSANS intensity profiles for \({\mu }_{0}H=140\) mT and \(\varGamma =0.5\) K; Bak-Jensen parameters estimations for Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge are used (see text). The feature in the red curve is a manifestation of the cut-off angle, whose position is shown with a dashed vertical line. When magnon damping increases, this local maximum vanishes making analysis of the cut-off angle impossible. g Typical SWSANS map numerically calculated for Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge if the magnons were relatively well-defined (\(\varGamma =0.5\) K, whereas the magnon energy near the cut-off \(\sim 2.5\) K). White circles centered at \(\pm {{\boldsymbol{k}}}_{s}\) (white dots) represent the cut-off angle beyond which the cross-section drastically diminishes.

Direct comparison of SWSANS scattering maps for Cr0.82Mn0.18 Ge and insulating Cu2OSeO3 is discussed in Supplementary Note 1 and illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1. Importantly, for the latter material, the well-defined magnons at the cut-off are characterized by energy \(\sim 1\) K and broadening below the experimental resolution \(\Gamma \lesssim 0.05\) K51. In contrast, for Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge magnons with energies \(\sim 2.5\) K should have \(\Gamma \gtrsim 1\) K according to the data analysis, thus being overdamped (see Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Here, this property can be associated with the highly disordered nature of the studied alloy. Noteworthy, typical SWSANS intensity in the field-polarized state is ca. two orders of magnitude weaker than the elastic SANS signals shown in Fig. 1b, c.

X-ray magnetic circular dichroism

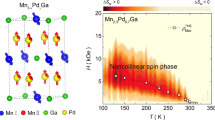

Results of the XMCD measurement at \(T=8\) K are shown in Fig. 3. Both Cr (Fig. 3a) and Mn (Fig. 3b) show a finite difference between x-ray absorption (XAS) curves measured at \(\pm 0.2\) T, which is well above the saturation field of Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge. The spectral line shape of Cr XAS and XMCD signals is similar to the one of the elemental Cr52 with the XMCD changing sign once from negative to positive at both \({L}_{3}\) (570–580 eV) and \({L}_{2}\) (580–590 eV) edges (Fig. 3a). In contrast, Mn spectra show multiplet features (Fig. 3b), indicating more localized orbitals, similar to the case of MnSi53 and Co8Zn8Mn454. Strikingly, the sign of the XMCD signal from Mn changes from positive at the main \({L}_{3}\) peak (635–640 eV) to negative at the \({L}_{2}\) edge, which demonstrates that the net magnetic moment of Mn is anti-aligned to the direction of the magnetic field, and also the magnetic moments of the Cr sub-lattice. The inversion behaviour between \({L}_{3}\) and \({L}_{2}\) edges is generic for XMCD spectra of \(3d\) transition metals and does not, by itself, indicate the presence of multiple magnetic environments or phase separation55. In our data, the opposite signs of the XMCD at the Cr and Mn edges—as opposed to the well-known sign reversal between the \({L}_{3}\) and \({L}_{2}\) edges of a single element—unambiguously indicate antiferromagnetic coupling between the fully field-polarized Cr and Mn sublattices, consistent with their ferrimagnetic ordering. Hence, Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge is, to our knowledge, the first example of a ferrimagnet among B20 materials. Notably, the antiferromagnetic interaction between Cr and Mn is hinted in the Cr1-xMnx Ge phase diagram reported by Sato et al. (see ref. 56), showing the spin-glass state for higher (\(x > 0.24\)) Mn concentrations.

Analytical approach

The model of a helimagnet with bond disorder was introduced in ref. 57. In the experimental study35, it was successfully applied to the description of the Mn1−xFexSi behavior main features for \(x > 0.1\), where only short-range magnetic order can be observed at low temperatures. In Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge, the spatial inhomogeneity of the exchange interaction is evident from element-selective XMCD measurements in the field-polarized state, which reveal opposite magnetization orientations between Cr and Mn ions (see above). These local antiferromagnetic Cr-Mn bonds compete with the ferromagnetic order of the matrix58, leading to a spin-glass state at higher Mn concentrations56.

We adopt the main ideas of the bond-disordered model to our current purposes. Our minimal model corresponds to the Bak-Jensen5 energy density

where \(\alpha\) corresponds to exchange interaction and \(\gamma\) to DMI, we neglect anisotropic contributions and allow for a spatially inhomogeneous exchange parameter. Noteworthy, it is easy to show that other types of disorder (e.g., spatial variations of \(\gamma\)) lead to the same results. For definiteness, we choose the magnetic field \({\bf{H}}\uparrow \uparrow \hat{z}\) and consider only the field-polarized phase. We use the linearized Landau-Lifshitz equation for the magnetization dynamics, see Supplementary Note 3 for details. It can be conveniently written for the combination of transverse components \({m}_{-}={m}_{x}-i{m}_{y}\) as

where \(\delta A({\bf{r}})=g{\mu }_{B}\delta \alpha ({\bf{r}})M\). After the Fourier transform in the clean case \(\delta \alpha ({\bf{r}})=0\), it yields the magnon spectrum of Eq. (1) with \(A=g{\mu }_{B}\alpha M\) and \({k}_{s}=\gamma /\alpha\).

Disorder [two last terms of Eq. (3)] scatters magnons, providing plane wave states with a finite lifetime. To proceed with the calculations, we assume that \(\delta A({\bf{r}})\) is spatially correlated on short distances and has a zero mean value. It is pertinent to note that we could also start with the disorder with a nonzero mean value. On the “mean field” level, it will renormalize energy scales of the problem and hence, e.g., periodicity of the spin structures28,29,30,34,35,57. In our case, a nonzero 〈δA(r)〉 results in renormalization of \(A\) and \({k}_{s}\) in the bare spectrum (1). After subtracting the mean value from \(\delta A({\bf{r}})\), we return to the problem at hand. The choice of a particular correlation function is not important on the qualitative level (until it is a short-range one, see Supplementary Note 4 for details); we take

where \(S\) is a dimensionless disorder strength and \(\kappa\) is its inverse correlation length. The natural assumption is that \(\kappa\) is defined by the lattice parameter scale \(1/a\), so \(\kappa \gg {k}_{s}\).

The first order in \(S\) (Born) correction to the magnon spectrum due to disorder-induced terms of Eq. (3) can be obtained using standard methods (see, e.g., ref. 59). Explicitly, we have

where the magnon self-energy due to the scattering on the disorder reads

Importantly, the pole for \(\omega ={\varepsilon }_{{{\bf{q}}}^{{\prime} }}\) defines the imaginary part of the self-energy and, thus, the magnon damping, whereas the poles \({q}^{{\prime} }=\pm i\kappa\) correspond to the magnon energy renormalization.

In the general case, the integration in Eq. (6) is quite cumbersome. It can be significantly simplified for low-energy magnons with \(|{\bf{q}}-{{\bf{k}}}_{s}|\ll {k}_{s}\). Using the on-shell approximation \(\omega ={\varepsilon }_{{\bf{q}}}\), we obtain the magnon damping in the simple form:

In the opposite case of \(|{\bf{q}}-{{\bf{k}}}_{s}|\gg {k}_{s}\), the shift in the magnon dispersion (1) is negligible and we obtain the result for usual ferromagnets

If \(|{\bf{q}}|\sim {k}_{s}\), the damping interpolates between the two limiting cases above, so \({\Gamma }_{{\bf{q}}}\sim {SA}{q}^{5}/{\kappa }^{3}\) but it is essentially anisotropic with respect to \({\bf{q}}={{\bf{k}}}_{s}\) point. This is evident, e.g., from the comparison of equal-energy points \({\bf{q}}=0\) and \({\bf{q}}=2{{\bf{k}}}_{s}\). For the former, the damping is zero, whereas for the latter \(\Gamma \ne 0\). Our findings are illustrated in Fig. 4a, b.

a Sketch of the magnon spectrum and damping for \({q}_{z}\) along \(\hat{z}\) axis. Here the external field \({\boldsymbol{H}}\uparrow \uparrow \hat{z}\) and dimensionless \({k}_{s}=0.2\). b Rescaled for illustration purposes, damping polar plots \(\varGamma ({\boldsymbol{q}}-{{\boldsymbol{k}}}_{s})/A\) for various \(|{\boldsymbol{q}}-{{\boldsymbol{k}}}_{s}|\) where the polar angle is for \({\boldsymbol{q}}\) lying in \(({q}_{z},{q}_{x})\)-plane with \({{\boldsymbol{k}}}_{s}\) being the origin of the coordinate system.

The correction to the magnon energy \({\varepsilon }_{{\bf{q}}}\) is defined mostly by \({q}^{{\prime} }\sim \kappa \gg {k}_{s}\) and hence is regime-independent. For \(q\ll \kappa\) it reads

so the spin-wave stiffness is diminished due to the disorder.

Now it is evident that low-energy magnons (i.e., those with \({\bf{q}}\) near \({{\bf{k}}}_{s}\)) are not “protected” against the disorder. Their kinetic energy is \(\propto {({\bf{q}}-{{\bf{k}}}_{s})}^{2}\), whereas the damping \(\propto |{\bf{q}}-{{\bf{k}}}_{s}|\). Usually, it is a manifestation of the perturbative expansion inapplicability and breakdown of a simple damped plane-wave picture for elementary excitations. In our case, localized magnons with energies inside the gap can emerge in regions of space where \(\delta A\) is predominantly negative. Indeed, in these regions, the local \({H}_{C2}\) is larger than the average, and the gap is smaller [cf. Equation (1)]. Moreover, upon field decrease, the “condensation” of these magnons should lead to the emergence of local noncollinear order (e.g., conical60), similar to the Bose-glass transitions in quantum magnets61,62,63,64.

Notably, the strong damping of low-energy magnons is in contradiction with common knowledge about long-wavelength (i.e., hydrodynamic) modes in ordered 3D magnets with impurities: since the disorder couples to the derivative terms of the corresponding equations of motion, the imaginary part of the spin wave dispersion is parametrically smaller than the real one and the excitations are well-defined. For instance, ferromagnets with fluctuating exchange interaction have \(\varepsilon \propto {q}^{2}\), whereas the damping scales as \({q}^{5}\)59, thus being negligible in the limit \(q\ll 1/a\) (see also refs. 65,66 for a discussion of 3D antiferromagnets).

Turning back to magnons with moderate momenta \(q\), we note that for SWSANS, the most important ones have \(q\sim {\theta }_{0}{k}_{i}\approx 5{k}_{s}\), corresponding to the cut-off angle. For strong disorder with \(S\sim 1\), Eq. (8) yields the damping comparable with their energy \({\varepsilon }_{{\bf{q}}}\). Hence, these magnons are ill-defined quasi-particles that cannot lead to a meaningful SWSANS signal.

Finally, it is pertinent to note that the polycrystalline nature of the sample should not be important for the conclusions above since \(d\sim 1\mu m\) is a relatively large length scale. It is easy to show that various orientations of the anisotropy axes and scattering on the grain boundaries provide negligible effects. For instance, the latter yields \({\Gamma }_{{\bf{q}}}/{\varepsilon }_{{\bf{q}}}\sim {\theta }_{0}^{2}/{k}_{i}d\ll 1\).

Discussion

Using spin wave small-angle neutron scattering and analytical theory for a model of disordered cubic helimagnet, we show that Cr0.82Mn0.18Ge does not possess well-defined magnetic excitations in the field-polarized phase. This conclusion aligns with previous observations of short-range helical structures in this compound.

Our study shows that the pronounced tunability of cubic B20 helimagnets properties can have an important drawback for practical applications when spin structures and phases with ill-defined quasi-particles emerge. In that regime, one can expect that perspective spintronic applications may fall short in terms of their anticipated performance due to suppression of magnon propagation. On the other hand, the disordered nature of these materials can lead to various short-range spin textures, for instance, in regions where the local saturation fields are smaller than the average. One can expect unusual transport properties and responses (see, e.g., Refs. 67,68) under such conditions, which are yet to be studied.

Data availability

The data is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Dzyaloshinsky, I. A thermodynamic theory of ‘weak’ ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 4, 241–55 (1958).

Moriya, T. Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 120, 91 (1960).

Dzyaloshinskii, I. E. Theory of helicoidal structures in antiferromagnets II. Metals. Sov. Phys. JETP 20, 665 (1965).

Ludgren, L., et al. Helical spin arrangement in cubic FeGe. Phys. Scr. 1, 69 (1970).

Bak, P. & Jensen, M. H. Theory of helical magnetic structures and phase transitions in MnSi and FeGe. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 13, L881 (1980).

Bogdanov, A. N. & Yablonskii, D. Thermodynamically stable ‘vortices’ in magnetically ordered crystals. Mixed State Magn. Sov. Phys. JETP 68, 100–3 (1989).

Bogdanov, A. & Hubert, A. Thermodynamically stable magnetic vortex states in magnetic crystals. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 138, 255–69 (1994).

Mühlbauer, S. et al. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science 323, 915–9 (2009).

Kishine, J. & Ovchinnikov, A. Theory of monoaxial chiral helimagnet. Solid State Phys. 66, 1–130 (2015).

Kurumaji, T. et al. Néel-type skyrmion lattice in the tetragonal polar magnet VOSe2O5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 237201 (2017).

Göbel, B., Mertig, I. & Tretiakov, O. A. Beyond skyrmions: Review and perspectives of alternative magnetic quasiparticles. Phys. Rep. 895, 1–28 (2021).

Hayami, S. & Yambe, R. Meron-antimeron crystals in noncentrosymmetric itinerant magnets on a triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. B 104, 094425 (2021).

Kuchkin, V. M., et al. Heliknoton in a film of cubic chiral magnet. Front. Phys. 11, 1201018 (2023).

Leonov, A. O. Meron-mediated phase transitions in quasi-two-dimensional chiral magnets with easy-plane anisotropy: successive transformation of the hexagonal Skyrmion lattice into the square lattice and into the tilted FM state. Nanomaterials 14, 1524 (2024).

Ohgushi, K., Murakami, S. & Nagaosa, N. Spin anisotropy and quantum Hall effect in the Kagomé lattice: chiral spin state based on a ferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 62, R6065 (2000).

Neubauer, A. et al. Topological Hall effect in the A phase of MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 186602 (2009).

Fert, A., Cros, V. & Sampaio, J. Skyrmions on the track. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 152–6 (2013).

Fert, A., Reyren, N. & Cros, V. Magnetic skyrmions: advances in physics and potential applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 1–15 (2017).

Li, S. et al. Magnetic skyrmions for unconventional computing. Mater. Horiz. 8, 854–68 (2021).

Chumak, A. V. et al. Advances in magnetics roadmap on spin-wave computing. IEEE Trans. Magn. 58, 1–72 (2022).

Raab, K. et al. Brownian reservoir computing realized using geometrically confined skyrmion dynamics. Nat. Commun. 13, 6982 (2022).

Lee, O., Msiska, R., Brems, M. A., Kläui, M., Kurebayashi, H., & Everschor-Sitte, K. Perspective on unconventional computing using magnetic skyrmions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, (2023).

Chumak, A., Serga, A. & Hillebrands, B. Magnonic crystals for data processing. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 50, 244001 (2017).

Weiler, M. et al. Helimagnon resonances in an intrinsic chiral magnonic crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 237204 (2017).

Garst, M., Waizner, J. & Grundler, D. Collective spin excitations of helices and magnetic skyrmions: Review and perspectives of magnonics in non-centrosymmetric magnets. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 50, 293002 (2017).

Flebus, B. et al. The 2024 magnonics roadmap. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 36, 363501 (2024).

Grigoriev, S. V. et al. Crystal handedness and spin helix chirality in Fe1-x CoxSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 037204 (2009).

Grigoriev, S. V. et al. Chiral properties of structure and magnetism in \({\text{Mn}}_{1-x}{\text{Fe}}_{x}\text{Ge}\) compounds: When the left and the right are fighting, who wins?. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 207201 (2013).

Fujishiro, Y., Kanazawa, N. & Tokura, Y. Engineering skyrmions and emergent monopoles in topological spin crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116 (2020).

Guang, Y. et al. Topological stability of spin textures in Si/Co-doped helimagnet FeGe. J. Phys. Mater. 7, 025009 (2024).

Kikuchi, T., et al. Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction as a consequence of a Doppler shift due to spin-orbit-induced intrinsic spin current. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 247201 (2016).

Bauer, A., et al. Quantum phase transitions in single-crystal Mn1-xFexSi and Mn1-xCoxSi: crystal growth, magnetization, ac susceptibility, and specific heat. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 82, 064404 (2010).

Glushkov, V. V. et al. Scrutinizing Hall effect in \({\text{Mn}}_{1-x}{\text{Fe}}_{x}\text{Si}\): Fermi surface evolution and hidden quantum criticality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 256601 (2015).

Bannenberg, L. J., et al. Magnetization and ac susceptibility study of the cubic chiral magnet Mn1-xFexSi. Phys. Rev. B 98, 184430 (2018).

Grigoriev, S. V., et al. Critical fluctuations beyond the quantum phase transition in Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya helimagnets Mn1-xFexSi. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 132, 588–95 (2021).

Kataoka, M. Spin waves in systems with long period helical spin density waves due to the antisymmetric and symmetric exchange interactions. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 56, 3635–47 (1987).

Maleyev, S. V. Cubic magnets with Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction at low temperature. Phys. Rev. B 73, 174402 (2006).

Nomura, T. et al. Phonon magnetochiral effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 145901 (2019).

Nomura, T. et al. Nonreciprocal phonon propagation in a metallic chiral magnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 176301 (2023).

Grigoriev, S. V. et al. Spin waves in full-polarized state of Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya helimagnets: Small-angle neutron scattering study. Phys. Rev. B 92, 220415 (2015).

Ukleev, V. et al. Spin wave stiffness and damping in a frustrated chiral helimagnet Co8Zn8Mn4 as measured by small-angle neutron scattering. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 023239 (2022).

Grigoriev, S., et al. Spin-wave stiffness in the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya helimagnet with ferrimagnetic ordering Cu2OSeO3. Phys. Rev. B 99, 054427 (2019).

Karube, K. et al. Metastable skyrmion lattices governed by magnetic disorder and anisotropy in \(\beta\)-Mn-type chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. B 102, 064408 (2020).

Sato, T., et al. Itinerant-electron-type helical–spin-glass reentrant transition in Cr0.81Mn0.19Ge. Phys. Rev. B 49, 11864 (1994).

Ukleev, V., et al. Observation of magnetic skyrmion lattice in Cr0.82Mn0.18 Ge by small-angle neutron scattering. Sci. Rep. 15, 2865 (2025).

Zeng, H. et al. Low-field induced topological Hall effect in chiral cubic Cr0.82Mn0.18 Ge alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 868, 159057 (2021).

Kim, D. & Schwartz, B. B. Neutron scattering in ferromagnetic dilute alloys. Phys. Rev. Lett. 21, 1744 (1968).

Cable, J. & Hicks, T. Magnetic-moment distributions for 3 d-transition-metal impurities in cobalt. Phys. Rev. B 2, 176 (1970).

Dewhurst, C. Graphical reduction and analysis small-angle neutron scattering program: GRASP. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 56 (2023).

Noll, T. & Radu, F. The mechanics of the VEKMAG experiment. Proc. of MEDSI2016, Barcelona, Spain 370-3 (2016).

Ukleev, V., et al. Helical spin dynamics in Cu2OSeO3 as measured with small-angle neutron scattering. Struct. Dyn. 12, 044301 (2025).

Yang, S. et al. Robust ferromagnetism of chromium nanoparticles formed in superfluid helium. Adv. Mater. 29, 1604277 (2017).

Zhang, S. L. et al. Engineering helimagnetism in MnSi thin films. AIP Adv. 6, (2016).

Ukleev, V. et al. Element-specific soft X-ray spectroscopy, scattering, and imaging studies of the skyrmion-hosting compound Co8Zn8Mn4. Phys. Rev. B 99, 144408 (2019).

Stöhr, J. Exploring the microscopic origin of magnetic anisotropies with X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) spectroscopy. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 200, 470–97 (1999).

Sato, T. et al. Magnetic phase diagram of Cr1−xMnxGe. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 57, 639–46 (1988).

Utesov, O. I., Sizanov, A. V. & Syromyatnikov, A. V. Spiral magnets with Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction containing defect bonds. Phys. Rev. B 92, 125110 (2015).

Klotz, J. et al. Electronic band structure and proximity to magnetic ordering in the chiral cubic compound CrGe. Phys. Rev. B 99, 085130 (2019).

Ignatchenko, V. & Iskhakov, R. Spin waves in a randomly inhomogeneous anisotropic medium. Sov. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 45, 526 (1977).

Utesov, O. I. & Syromyatnikov, A. V. Cubic B20 helimagnets with quenched disorder in magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 99, 134412 (2019).

Hong, T., et al. Evidence of a magnetic Bose glass in \({({\text{CH}}_{3})}_{2}{\text{CHNH}}_{3}\text{Cu}{({\text{Cl}}_{0.95}{\text{Br}}_{0.05})}_{3}\) from neutron diffraction. Phys. Rev. B 81, 060410 (2010).

Yu, R. et al. Bose glass and Mott glass of quasiparticles in a doped quantum magnet. Nature 489, 379–84 (2012).

Utesov, O., Sizanov, A. & Syromyatnikov, A. Localized and propagating excitations in gapped phases of spin systems with bond disorder. Phys. Rev. B 90, 155121 (2014).

Syromyatnikov, A. V. & Sizanov, A. V. Magnetically ordered phase near transition to Bose-glass phase. Phys. Rev. B 95, 014206 (2017).

Edwards, S. & Jones, R. A green function theory of spin waves in randomly disordered magnetic systems. I. The ferromagnet. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 4, 2109 (1971).

Wan, C., Harris, A. & Kumar, D. Heisenberg antiferromagnet with a low concentration of static defects. Phys. Rev. B 48, 1036 (1993).

Ritz, R., et al. Formation of a topological non-Fermi liquid in MnSi. Nature 497, 231–4 (2013).

Barsukov, I. et al. Giant nonlinear damping in nanoscale ferromagnets. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav6943 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Authors thank S. V. Grigoriev and K. A. Pschenichnyi for fruitful discussions. SANS experiments were performed at the Swiss spallation neutron source SINQ, Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, Switzerland according to the proposal 20230352. C.L., F.R., V.U. acknowledge financial support of the VEKMAG end station at the BESSY-II by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF 05K10PC2, 05K10WR1, 05K10KE1) by HZB and by the German Research Foundation via Project No. SPP2137/RA 3570. O. I. U. acknowledges financial support from the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) in the Republic of Korea through Project No. IBS-R024-D1. P.R.B. acknowledges SNSF Postdoc. Mobility grant P500PT_217697 for financial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S. and L.C. synthesized and characterized the sample; V.U., J.S.W., and P.R.B. performed neutron scattering measurements; V.U., C.L., and F.R. carried out XMCD experiments; O.I.U. developed the analytical approach; V.U., C.L., O.I.U., and J.S.W. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. O.I.U., L.C., and V.U. jointly conceived the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Utesov, O.I., White, J.S., Baral, P.R. et al. Overdamped magnons in the field-polarized phase of cubic helimagnet. NPG Asia Mater 18, 2 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-025-00630-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-025-00630-7