Abstract

Various crosslinked PDMS films incorporating cyclic epoxy groups were prepared by UV-induced acid generation and thermal curation and evaluated as CO₂-selective permeable membranes. These free-standing, ultrathin PDMS films (~100 nm thick) were formed by crosslinking side-epoxy-PDMS, which contains multiple epoxy groups, and end-epoxy-PDMS, which has epoxy groups at the polymer ends only. Gas permeation tests revealed that the films crosslinked with end-epoxy-PDMS exhibited high CO₂ permeance. Specifically, the membrane composed of UV-crosslinked end-epoxy-PDMS (Mn = 20,000, thickness ~ 200 nm) achieved a CO₂ permeance of 5200 GPU and a CO₂/N₂ selectivity of 11.0. Reducing the membrane thickness increased the permeance without affecting selectivity. However, shortening the siloxane chain, using side-epoxy-PDMS, or reducing the linker length led to decreases in both permeance and selectivity. For example, side-epoxy-PDMS (Mn = 30,000, Si-H/O-Si-O ratio = 37%, thickness ~ 200 nm) had a CO₂ permeance of 400 GPU and a CO₂/N₂ selectivity of 1.16. These results indicate that a lower crosslinking density and longer end-epoxy-PDMS siloxane chains are advantageous for CO₂ dissolution and diffusion, resulting in superior CO₂ permeance and selectivity compared with composed of side-epoxy-PDMS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere are major contributors of climate change, and reducing emissions alone is not sufficient; thus, negative emission technologies that directly reduce CO₂ levels in the air are needed [1]. Various approaches are being considered to achieve this goal, including technologies that combine carbon capture and storage [2], cooling the CO₂ to generate a solid (dry ice) [3], and biochemical CO₂ fixation technologies [4], such as afforestation. Recently, membrane separation technology has attracted attention for direct air capture (DAC) [5,6,7]. Initially, membrane-based DAC (m-DAC) was determined to be impractical for low-concentration CO₂ capture from the atmosphere. However, the very recently developed membranes with high CO₂ permeance based on very thin films have led to m-DAC being considered a feasible approach [5, 6].

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) has been widely studied for gas separation, permeation filtration, and nanofiltration applications as a benchmark rubber-like membrane material with high permeance [8,9,10,11]. For example, Fujikawa et al. reported freestanding siloxane nanomembranes with CO₂ permeance exceeding 40,000 GPU (1 GPU = 7.5 × 10−12 m3(STP) · m−2 · s−1 · Pa−1, where STP is standard temperature and pressure) using common, commercially available silicone resins [12]. The ultrahigh gas permeance and maintained selectivity of these membranes demonstrate their potential to capture CO₂ efficiently, even from atmospheric air. PDMS-crosslinked membranes have high gas permeance but low CO₂ selectivity, and our understanding of their optimal structure to increase selectivity is limited [13, 14].

In this study, we report the synthesis of reactive PDMS with alicyclic epoxy groups photocrosslinked into two ways (via the side chain and terminus) and the preparation and evaluation of CO₂-selective permeable PDMS-crosslinked nanomembranes. By creating crosslinked membranes from PDMS with well-defined primary structures, we attempted to elucidate the correlation between the crosslinked PDMS structure and permeation properties.

Alicyclic epoxy groups are widely used as crosslinking units in various polymers. Since epoxy groups can react with the hydroxyl groups of their ring-opening products, chain crosslinking can occur between the epoxy units alone without the need for additional crosslinking agents [15, 16]. Additionally, photoinitiated crosslinking of these units is possible in the presence of a photoacid generator, which offers advantages in terms of controllability during membrane manufacture. Crosslinking using alicyclic epoxies and photoacid generators offers additional advantages, such as the absence of oxygen inhibition, generally low shrinkage during curation, and high dimensional stability [16].

Materials and methods

Materials

Hexamethyl cyclotrisiloxane (D3), 1,3,5,7-tetramethyl cyclotetrasiloxane (D4’(H), 1,1,3,3-tetramethyldisiloxane (SHT), and the Karstedt catalyst were purchased from TCI. Toluene, sulfuric acid, methanol, and hexane were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation. Hydrogen hexachloroplatinate(IV) hexahydrate and 1,2-epoxy-4-vinylcyclohexane were purchased from Daicel Corporation. CATA211 was purchased from Arakawa Chemical Industries, Ltd. Poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) (PSS) was purchased from Sigma‒Aldrich. The polyacrylonitrile (PAN) substrate was purchased from SolSep BV.

Synthesis of hydrosilyl PDMS and alicyclic epoxy PDMS

Hydrosilyl PDMSs were prepared via the ring-opening polymerization of cyclic siloxanes. In a Schlenk flask under a N₂ atmosphere, a toluene solution of hexamethyl cyclo-trisiloxane (D3), 1,3,5,7-tetramethylcyclotetrasiloxane (D4’(H), 1,1,3,3-tetramethyldisiloxane (SHT), and methanesulfonic acid were mixed as the monomers, terminal agent, and acid catalyst, respectively. The amount of catalyst added was 0.304 wt%. Typically, each solution was stirred at 50 °C for 5 h and then at room temperature for 19 h, and the equilibrium reaction was maintained under a N₂ atmosphere. The average molecular weight was adjusted on the basis of the molar ratio of D3 to SHT [17]. After the reaction, the raw materials and byproducts were removed with methanol (poor solvent), and the solvent was removed by evaporation. Finally, clear and colorless products were obtained. All the resulting reactive PDMSs were transparent liquids.

Alicyclic epoxy PDMSs were synthesized by hydrosilylation of H-ended PDMS and 1,2-epoxy-4-vinylcyclohexane with the Karstedt catalyst or hydrogen hexachloroplatinate(IV) hexahydrate. As illustrated in Fig. 1, in a Schlenk flask in a glove box, presynthesized Si-H-ended PDMS or pendant Si-H PDMS as the monomer and hydrogen hexachloroplatinate (IV) hexahydrate (or Karstedt’s catalyst) in hexane solution were mixed. The amount of catalyst added was 0.699 wt%. The solutions were stirred at 50 °C for 5 h to introduce 1,2-epoxy-4-vinylcyclohexane into the Si-H-ended PDMS or pendant Si-H PDMS by hydrosilylation. The raw material and byproducts were removed with methanol (poor solvent), and the solvent was removed by evaporation. Finally, a transparent oil was obtained. Some alicyclic epoxy-modified silicones underwent catalyst deactivation, after which the solution became brown. The oily products were washed with methanol for purification, and the methanol was evaporated.

All the resulting reactive PDMSs were transparent liquids. The epoxy-modified PDMSs were characterized by ¹H-NMR and SEC analyses.

Thick and thin crosslinked PDMS films prepared via photoacid generation

To prepare thick crosslinked PDMS films, alicyclic epoxy PDMS oil and the UV initiator CATA211 (10:1.0 unit molar ratio) were mixed without solvent using a rotary mixer (Awatori Rentaro ARV-310P, Thinky, Japan) typically at 1000 rpm and 60.0 kPa for 60 s. After degassing, the mixture was placed in a Teflon Petri dish, and crosslinking polymerization was initiated by UV irradiation at room temperature for 15 min using an unfiltered ultrahigh-pressure mercury vapor lamp (Optical Modulex, Ushio Inc., Japan 14.0 W/cm2) or a UV-LED (OMRON, ZUV-C30H, wavelength 365 nm, 12.0 mW/cm2). Photocrosslinking was typically conducted by UV irradiation at room temperature for 15 min followed by heating at 50 °C for 2 h. The film thickness was measured with a digital caliper.

Ultrathin films with thicknesses of several hundred nanometers were prepared for gas permeation experiments. A diagram of the workflow for the preparation of multilayer membranes with photocured PDMS films for gas permeation analysis is shown in Fig. 2. To prepare a substrate with a sacrificial polymer film, a 15 wt% aqueous PSS solution was spin-coated (3,000 rpm for 40 s) onto a glass substrate and heated to 100 °C for 5 min [12, 18]. A 10 wt% hexane solution of alicyclic epoxy-terminated PDMS and CATA211 (10.0:1.00 unit molar ratio) was spin-coated (1,000 rpm for 40 s) and heated at 100 °C for 3 min for prebaking. UV irradiation and thermal treatment were performed using a UV-LED in a similar manner to that used for the thick films.

After photocrosslinking, the PDMS samples were immersed in water together with the substrates. The crosslinked PDMS films naturally peeled off and floated to the water surface and were then transferred to an uncoated microporous PAN support membrane (SolSep BV, Netherlands, type ID, UF 010104; Mw cutoff values ∼20 kDa, retention >95%) [12, 18, 19]. Multilayer membrane samples with Kapton tape attached to standardize the permeation area were used to evaluate gas permeance [12, 18].

The film thickness measurement system (Filmetrics, F20-UV) using 180-degree reflection is easy to operate and has an effective film thickness measurement range of 0.1–40 µm. Large errors were observed with films with thicknesses of 100 nm or less. In contrast, when spectroscopic ellipsometry (OTSUKA ELECTRONICS, FE-5000S) was used, high-accuracy measurements were possible even for films with thicknesses of 100 nm or less. Analysis using spectroscopic ellipsometry was difficult when the film thickness exceeded 1 micron.

Characterization of the crosslinked PDMS films

The crosslinked PDMS thick films were soaked and washed in tetrahydrofuran (THF) for 24 h to remove noncrosslinked species. The film weights were measured before and after complete drying. The gelation rate (%) and swelling rate (%) were calculated according to the following equations.

Tensile tests were conducted at room temperature using a Shimadzu machine (model number EZ-LX 5 kN) at a tensile speed of 10 mm/min. The samples were ~1.00 mm thick and 2.00 mm wide, and the distance between the grips was 18.0 mm. Samples were prepared using a punching dumbbell (SD type lever-controlled sample cutter, shape standard SDL-100). The thermal properties of the reactive PDMS and crosslinked PDMS films were analyzed by DSC (model number DSC8500, PerkinElmer). The temperature increased at a rate of 30.0 °C/mm, and the measurement temperature range was −180 to 150 °C.

Gas permeation experiments

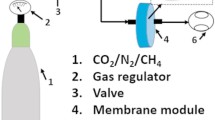

The polymer membrane samples were prepared and gas permeation measurements were performed according to previously reported methods [12, 18]. The permeation of CO₂ and N₂ through the membrane was investigated separately at room temperature (25 ± 1 °C) with pressure differences of 50, 100, 150, and 200 kPa on the supply and permeation sides. The permeate gas flux was monitored using a bubble flowmeter. Gas permeation was assessed with pure gases, and several replicates of each membrane sample were analyzed. The ideal selectivity (ratio) of two different gases through the crosslinked PDMS membranes was calculated by taking the ratio of the different gas permeabilities.

Results

Synthesis of alicyclic epoxy-terminated PDMS

The synthesis of alicyclic epoxy-modified PDMS was performed by reacting hydrosilyl PDMS with 1,2-epoxy-4-vinylcyclohexane [15], as shown in Fig. 2. Two types of epoxy-modified PDMSs (end-epoxy and side-epoxy) were synthesized from the corresponding hydrosilyl PDMSs. Hydrosilyl PDMSs with different average molecular weights were also prepared. The average molecular weight could be controlled by adjusting the ratio of the terminal agent to D3 (and D4’(H)), and the expected average molecular weights were consistent with those expected on the basis of the molar ratio [20]. All the reactive PDMSs with alicyclic epoxy units were obtained in high yields, and their chemical structures were characterized by ¹H-NMR (see SI. 1) and SEC (see SI. 2), as summarized in Table 1. In addition, alicyclic epoxy-modified PDMSs with different percentages of epoxy groups were synthesized. The lowest percentage of reactive PDMS was ~60%. One hundred percent modification was confirmed by the disappearance of peaks from the terminal hydrosilyl groups in the ¹H-NMR spectrum.

Crosslinked PDMS films prepared via photoacid generation

Crosslinked PDMS elastomers were prepared via a ring-opening crosslinking reaction (curing) of the alicyclic epoxy units of the PDMSs [16], which was catalyzed by acid generated using an acid-generating photocatalyst upon UV irradiation. Traditionally, major silicone polymer products have been prepared by thermal curing via hydrosilylation and dehydration (condensation) [21]. Recently, photocuring systems have become popular in the manufacture of silicone products for environmental and energy conservation applications [3]. UV-cured silicone systems can be classified into (meth)acryloyloxy-based silicone polymer systems with radical photoinitiators, thiol-ene-based silicone polymer systems, and systems based on the cationic photopolymerization of epoxy groups [16].

UV irradiation of neat alicyclic epoxy-modified PDMSs produced soft self-supporting thick films with a thickness of 1 mm (see SI. 3), as determined via swelling and gel fraction tests, DSC, and stress–strain curve measurements. The formation of a three-dimensional polymer network (gelation) was qualitatively confirmed by observing the swelling of the films but not their dissolution in THF. Interestingly, crosslinked films could be formed from both side- and end-epoxy-type PDMS, even with an epoxy group content of 60%. This finding indicates that even very few epoxy units at the end of high-molecular-weight PDMS can induce the formation of an effective crosslinked structure. This also indicates that the relatively hydrophilic epoxy groups and their ring-opening products tend to separate from the oily PDMS and become concentrated.

Gelation and swelling rates

The ring-opening crosslinking reaction of epoxy units proceeds by the acid generated upon UV irradiation. Therefore, the crosslinking reaction continues even after light irradiation is stopped. Figure 3 shows the changes in the gelation fraction rates as a function of curing time during photocationic heat treatment of the sample End-epoxy-PDMS 20 K,100%. The film was in a sol state immediately after photoirradiation (15 min) without heat curation. After 1.5 h of curing at 50 °C, the film gelated, with a gelation fraction of 79.3%. As the curing duration increased, the gelation fraction increased slowly, reaching saturation at ~90% after almost 5 h. When the sample was cured at 100 °C, the gelation fraction reached 98.4% in 1 h, which was close to saturation. The typical gelation fractions and swelling ratios of the crosslinked PDMS films prepared under different crosslinking conditions in THF are shown in Table 2.

The appearance of tackiness was probably due to uneven crosslinking. The high viscosity of the polymer prior to crosslinking under solvent-free conditions might make uniform mixing of the photoacid generator difficult. In contrast to side-chain alicyclic PDMS, crosslinked end-epoxy-PDMS formed a tacky soft film with a high degree of swelling. The End-epoxy-PDMS 20 K,100% sample cured at 50 °C for 2 h, had a gelation rate of 82.4% and a swelling rate of 560%. The same sample cured at a higher temperature for a shorter irradiation duration had a gelation rate of 97.4%. Increasing the gelation rate not only decreased the swelling rate and maximum strain but also increased the elastic modulus and breaking strength. As the amount of terminal agent introduced decreased, the swelling rate increased, which is thought to indicate an increase in the distance between crosslinking points. When PDMS with a high average molecular weight of 30 K was used, a crosslinked film with a high swelling rate was generated under the same crosslinking conditions. A very loose gel with a swelling rate of 920% was also produced from a sample with a terminal agent introduction rate of 64%, but this process required strong UV irradiation for a prolonged duration and a long curing duration at a relatively high temperature.

Stress–strain curve

Typical stress–strain curves of the crosslinked PDMS thick films (~1 mm thick) are shown in Fig. 4, and the results, along with the results of the swelling tests, are summarized in Table 2. As shown in the inset of Fig. 4, the crosslinked thick PDMS film formed with 100% end-epoxy-PDMS 30 K was colorless, transparent, flexible, and self-supporting. As mentioned above, the side-chain-type epoxy PDMS films (side-epoxy-PDMS 10 K,10%) crosslinked under solvent-free conditions were brittle and difficult to fabricate with the punch, and despite their tackiness, they could not be assessed via the tensile tests (see SI. 3).

Typical stress‒strain curves of the UV-crosslinked films fabricated with three terminal alicyclic epoxy PDMS samples (a, b, c 20K_100%; d 30K_100%; and e 20K_64%). The curing conditions were 15 min of UV irradiation and 2 h of curing at 50 °C in a, c, d; 65 min of UV irradiation at 14.0 W/cm2 (ultrahigh-pressure mercury lamp, USIO Optical Modulex) in e; and 3 min of UV irradiation and 40 min of curing at 150 °C in b

All the end-unit crosslinked PDMS films showed a high degree of swelling (>400%) but were gels and not sols. The swelling ratios of these films decreased with increasing epoxy group incorporation, and crosslinked polymers with longer PDMS chains had larger swelling ratios. As expected, the elastic modulus and breaking point were lower and the elongation at break was greater for the samples with higher degrees of swelling. These results indicate that, as expected, the introduction of an epoxy group at the end of the polymer leads to the formation of an effective crosslinked structure.

The high average molecular weight polymers had a lower modulus and breaking strength and higher maximum strain than those with low average molecular weights. This finding indicates that the former films had a greater distance between crosslinking points (Fig. 4a, d). PDMS films cured at higher temperatures with shorter irradiation durations presented higher moduli and breaking strengths and lower maximum strains (Fig. 4b, c). The polymers with a lower percentage of epoxy units at the ends had a lower modulus and breaking strength and higher maximum strain than did the polymer with 100% epoxy content.

DSC measurements

The thermal properties of the hydrosilyl and alicyclic epoxy-modified PDMSs before and after crosslinking were investigated by DSC. Figure 5 shows typical DSC thermograms, and the numerical data are summarized in Table 3. Hydrosilyl-terminated PDMSs revealed glass transition peaks at approximately −127 °C only (See SI. 4). The glass transition temperatures of all terminal alicyclic epoxy PDMSs with and without crosslinking ranged from −128 to −127 °C, which is the same as the glass transition temperature of the original PDMS. This finding indicates that for end-crosslinked PDMS polymers with molecular weights greater than 20,000 before crosslinking, the crosslinking structure has little effect on the glass transition of the PDMS backbone. All noncrosslinked end-epoxy PDMS polymers presented exothermic and endothermic peaks at −79.9 to −73.1 °C and −47.2 to −45.4 °C, respectively, due to aggregation and dispersion of the epoxy sites at the PDMS ends.

In contrast with intact PDMS, the end-epoxy-PDMSs showed peaks associated with crystallization and melting temperatures. This is likely due to the aggregation and dispersion of alicyclic epoxy units. In addition, since only the glass transition temperature was observed for Side-epoxy-PDMS, we consider that the alicyclic epoxy groups are unlikely to have aggregated and dispersed in PDMS with alicyclic epoxy groups on the side chains owing to steric hindrance, in contrast with PDMS with alicyclic epoxy groups on the ends.

The crosslinked end-epoxy-PDMS film also exhibited similar endothermic and exothermic peaks, and both peak temperatures decreased after crosslinking. We assume that this was due to crosslinking restricting the mobility of the polymer chains and hindering crystal growth, making the formation of arrays by crystallization difficult. The same can be said for the melting temperature. For side-chain type PDMS, the glass transition became unclear both in the presence and absence of crosslinking.

Evaluation of gas permeance

Gas-selective permeance was evaluated using the alicyclic epoxy-crosslinked PDMS films (Table 4). To clarify the relationship between the film thickness and gas-selective permeance, thin films (thickness < 1 µm) composed of crosslinked PDMS were prepared by spin-coating and transferred to non-gas-selective porous PAN films (support films) and evaluated in a similar manner to that reported by Fujikawa et al. [12, 18]. Gel crosslinking of the thin films was confirmed when the shape of the membrane at the air/water interface was retained after the removal of the sacrificial layers by dissolution.

The results in Fig. 6a, b show that the CO₂ permeance tended to increase as the film thickness decreased and that the CO₂/N₂ selectivity remained stable from 10 to 12, regardless of the film thickness. These results revealed that CO₂ permeance could be increased while maintaining CO₂ selectivity by reducing the membrane thickness [12, 22]. Our results reaffirm that the use of defect-free ultrathin films is a meaningful strategy for the development of highly permeable membranes with practical applications in large-scale CO₂ capture.

Gas permeation measurements of alicyclic epoxy-modified silicone crosslinked thin films: a CO₂ permeance, b CO₂/N₂ selectivity and c CO2 permeability. The indicated samples (*) were prepared by UV-LED irradiation (12.0 mW/cm²) for 3 min and heating to 150 °C for 40 min. The other samples were prepared by UV-LED irradiation (12.0 mW/cm²) for 15 min and heating to 50 °C for 2 h. The gas permeance was calculated as the average of the values determined at different pressures

A plot of CO₂ permeability is shown in Fig. 6c. Even for the crosslinked PDMS films prepared under the same conditions, the CO₂ permeability decreased as the film became thinner, although, in principle, the same materials would be expected to exhibit similar CO₂ permeabilities. This suggests that the structure of the crosslinked membrane may change depending on the thickness of the membrane in films thinner than 1 micron [12]. Moreover, gas permeation is generally governed by both surface adsorption/desorption and internal diffusion processes. In the case of ultrathin films, the surface adsorption/desorption process is thought to dominate, which is not the case for the thick films. In the future, it will be necessary to develop specific structural evaluation methods for thin films for comparison with bulk materials.

Permeation tests revealed that the 10 K, 10% side-chain epoxy PDMS crosslinked membranes exhibited high CO₂ selectivity and permeance, similar to that of terminal epoxy PDMS. However, the 30 K, 37% side-chain epoxy PDMS crosslinked membrane showed a significant decrease in gas permeance and almost no CO₂ selectivity. Although there was no significant difference in the number of epoxy groups introduced, the crosslinking between high-molecular-weight polymers likely increased the crosslinking density, resulting in enhanced gas barrier properties. This suggests that the high crosslinking density of the side-chain alicyclic epoxy PDMS membranes limited CO₂ diffusion, and the decreased diffusion rate led to a reduction in permeance. Therefore, CO₂ separation membranes should be designed with a crosslinked structure that does not hinder CO₂ diffusion. Notably, the films created under these conditions were extremely fragile, and many, except those with reported data, could not withstand permeation measurements.

Conclusion

We synthesized PDMSs with site-selectively introduced alicyclic epoxy units, crosslinked the PDMS films by UV irradiation-induced acid generation and thermal curation, and evaluated the films as CO₂-selective permeable membranes. In contrast to conventional hydrosilyl crosslinking between PDMS and crosslinkers by reaction between vinyl and hydrosilyl groups, alicyclic epoxy PDMS monomers can be cured by addition with one type of polymer and can be controlled by light. It was possible to produce crosslinked films with side-epoxy-PDMS with many epoxy groups and end-epoxy-PDMS with high molecular weights with nearly 100% conversion. Efficient crosslinking was induced by the concentration of epoxy sites owing to phase separation from PDMS.

End-type and side-chain-type PDMSs can both be used to create thick and free-standing ultrathin films with thicknesses of ~100 nm. The gas permeation measurements revealed these films to be effective CO₂-selective permeable membranes with high gas permeance. In particular, the end-epoxy-PDMS crosslinked thin films were found to be highly CO₂-selective membranes with high gas permeance. There were differences in the crosslinked structures of the end-epoxy-PDMSs and side-epoxy-PDMSs, which affected the gas transport properties of the membrane. For end-epoxy-PDMS with an average molecular weight of 20,000 and a membrane thickness of 1 µm, the CO₂ permeance was 3500 GPU, and the CO₂/N₂ selectivity was 10.8. This is equivalent to the performance of a commercially available silicone resin. As the thickness of the membrane decreased, the permeance increased without changing the selectivity. In contrast, when the siloxane chain of end-epoxy-PDMS was shortened, side-epoxy-PDMS was used, the distance between crosslinking points was drastically reduced, the permeance and selectivity decreased. We believe that a low crosslinking density and high degree of freedom of the long siloxane chain are advantageous for the dissolution and diffusion of CO₂ into the silicone membrane.

References

Li S, Guta Y, Andrade MFC, Hunter-Sellars E, Maiti A, Varni AJ, et al. Competing kinetic consequences of CO2 on the oxidative degradation of branched poly(ethylenimine). J Am Chem Soc. 2024;146:28201–13.

Ma J, Li L, Wang H, Du Y, Ma J, Zhang X, et al. Carbon capture and storage: history and the road ahead. Engineering. 2022;14:33–43.

Han X, Ostrikov KK, Chen J, Zheng Y, Xu X. Electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to solid carbon: development, challenges, and perspectives. Energy Fuels. 2023;37:12665–84.

Karishma S, Kamalesh R, Saravanan A, Deivayanai VC, Yaashikaa PR, Vickram AS. A review on recent advancements in biochemical fixation and transformation of CO2 into constructive products. Biochem Eng J. 2024;208:109366.

Fujikawa S, Selyanchyn R, Kunitake T. A new strategy for membrane-based direct air capture. Polym J. 2021;53:111–9.

Fujikawa S, Selyanchyn R. Direct air capture by membranes. MRS Bull. 2022;47:416–23.

Ohshita J, Okonogi T, Kajimura K, Horata K, Adachi Y, Kanezashi M, et al. Preparation of amine-and ammonium-containing polysilsesquioxane membranes for CO2 separation. Polym J. 2022;54:875–82.

Pan Y, Chen G, Liu J, Li J, Chen X, Zhu H, et al. PDMS thin-film composite membrane fabricated by ultraviolet crosslinking acryloyloxy-terminated monomers. J Memb Sci. 2022;658:120763.

Sandru M, Sandru EM, Ingram WF, Deng J, Stenstad PM, Deng L, et al. An Integrated Materials Approach to Ultrapermeable and Ultraselective CO2 Polymer Membranes. Science. 2022;376:90–94.

Cao Q, Ding X, Zhao H, Zhang L, Xin Q, Zhang Y. Improving gas permeation performance of PDMS by incorporating hollow polyimide nanoparticles with microporous shells and preparing defect-free composite membranes for gas separation. J Memb Sci. 2021;635:119508.

Firpo G, Angeli E, Repetto L, Valbusa U. Permeability thickness dependence of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membranes. J Memb Sci. 2015;481:1–8.

Fujikawa S, Ariyoshi M, Selyanchyn R, Kunitake T. Ultra-fast, selective CO2 permeation by free-standing siloxane nanomembranes. Chem Lett. 2019;48:1351–4.

Liu M, Nothling MD, Zhang S, Fu Q, Qiao GG. Thin film composite membranes for postcombustion carbon capture: polymers and beyond. Prog Polym Sci. 2022;126:101504.

Firpo G, Angeli E, Repetto L, Valbusa U. Gas sorption, diffusion, and permeation in poly(dimethylsiloxane). J Polym Sci B Polym Phys. 2000;38:415–34.

Morita Y, Tajima S, Suzuki H, Sugino H. Thermally initiated cationic polymerization and properties of epoxy siloxane. J Appl Polym Sci. 2006;100:2010–9.

Sangermano M, Razza N, Crivello JV. Cationic UV-curing: technology and applications. Macromol Mater Eng. 2014;299:775–93.

Hu P, Madsen J, Skov AL. One reaction to make highly stretchable or extremely soft silicone elastomers from easily available materials. Nat Commun. 2022;13:1–10.

Selyanchyn O, Selyanchyn R, Fujikawa S. Critical role of the molecular interface in double-layered pebax-1657/PDMS nanomembranes for highly efficient CO2/N2 gas separation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12:33196–209.

Wijmans H, Synthetic membranes—On the formation mechanism of membranes and on the concentration polarization phenomenon in ultrafiltration. Ph.D. thesis. University of Twente; 1984.

Hu W-J, Xia Q-Q, Pan H-T, Chen H-Y, Qu Y-X, Chen Z-Y, et al. Green and rapid preparation of fluorosilicone rubber foam materials with tunable chemical resistance for efficient oil–water separation. Polymers. 2022;14:1628.

Jiang B, Shi X, Zhang T, Huang Y. Recent advances in UV/thermal curing silicone polymers. Chem Eng J. 2022;435:134843.

Selyanchyn R, Fujikawa S. Molecular hybridization of polydimethylsiloxane with zirconia for highly gas permeable membranes. ACS Appl Polym Mater. 2019;1:1165–74.

Acknowledgements

This study was also supported by the Moonshot Research and Development Program (JPNP18016), commissioned by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO).

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Kumamoto University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hashiguchi, S., Kawata, M., Nakano, T. et al. Photocrosslinked films composed of polydimethylsiloxane bearing alicyclic epoxy units and their CO₂-selective permeation properties. Polym J 57, 985–994 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-025-01052-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-025-01052-6