Abstract

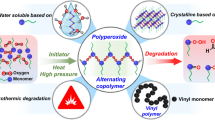

2-Methylene-4H-benzo[d][1,3]dioxin-4-one, a cyclic hemiacetal ester prepared via the intramolecular esterification of acetyl salicylic acid, is an electron-rich vinyl monomer that can undergo radical polymerization to afford vinyl polymers with excellent thermal and mechanical properties. In this study, the aromatic ring was substituted with various substituents. Substitution with electron-donating groups resulted in instability and low yields, whereas substitution with two tert-butyl groups at the 6- and 8-positions increased the stability against moisture and reduced the reactivity in radical polymerization. Thus, the monomer afforded an almost ideal alternating copolymer with dimethyl maleate. Compared with the copolymers with nonsubstituted monomers, the copolymers with vinyl acetate presented a higher glass transition temperature, suggesting that the two tert-butyl groups effectively increased the thermal stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

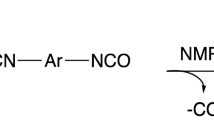

Ketene acetal esters (KAEs) are vinyl compounds in which one side is a vinyl ester and the other is a vinyl ether. This chemical structure gives KAEs the potential to act as monomers for radical and cationic polymerizations. However, no attention has been given to such polymerizations, and the available literature reports KAEs as synthetic intermediates [1, 2] or acylating agents [3,4,5] Typically, KAEs can be synthesized from the Markovnikov addition of carboxylic acid and ethinyl ether [6, 7] However, Babin and Bennetau reported the synthesis of cyclic KAEs via intramolecular esterification between an enol and acyl chloride (Scheme 1); that is, O-acetyl salicyloyl chloride (1a) was treated with triethylamine (Et3N) to form a cyclic KAE named ‘dehydroaspirin’ (2a) [8] for its ability to undergo hydrolysis to acetyl salicylic acid (4a, aspirin). Compared with other KAEs, 2a has the advantages of readily available raw materials and a facile synthetic protocol. Thus, we previously reported the radical [9] and cationic [10] polymerizations of 2a under various conditions. As expected from its chemical structure, 2a behaves as an electron-rich vinylidene monomer, similar to vinyl acetate (VAc) and vinyl ethers. The Q and e values in the Price–Alfrey equation were 0.13 and −1.14, respectively, and 2a copolymerized with VAc and methyl methacrylate (MMA) [10].

Notably, the radical polymerization of KAEs caused the appearance of hemiacetal ester (HAE) moieties over the main chain. Because an HAE is reversibly cleaved by heat or an acid catalyst to a carboxylic acid and a vinyl ether, it is recognized as a motif of dynamic covalent chemistry [11] Otsuka et al. reported reversible polyaddition [12] and pendant modification [13,14,15] using HAE formation, where HAEs functioned as initiators of cationic polymerization in the presence of Lewis acids [16,17,18,19]. HAEs undergo hydrolysis by acid and base catalysts, such as acetals and esters, and the reaction is applied to the main-chain scission of polymers [20, 21]. Notably, the hydrolysis of the HAE moieties in the polymers of cyclic KAEs, including 2a, led to main-chain scission [9, 10, 22,23,24]. The reaction mechanism was explained by the combination of hydrolysis of HAEs and 1,3-dicarbonyl moieties (retro-Claisen condensation) [24]. Thus, cyclic KAEs are attractive for the incorporation of degradable sites into the main chain of vinyl polymers. In contrast, the rigidity of 2a units, which consist of six-membered cyclic HAEs and aromatic rings, effectively increases the thermal stability and mechanical properties of polymers [25, 26].

Despite these features, cyclic KAEs are associated with several critical issues. Electron-rich vinylidene groups allow hydrolysis in air [8]. This instability is similar to that of ketene acetals, which are more moisture sensitive and easily decompose into the corresponding alcohol [27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. In addition, homopolymer 2a is soluble only in highly polar solvents such as N,N-dimethyl formamide (DMF) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), which restricts the polymerization conditions [9]. Therefore, cyclic KAEs with improved stability against moisture that can afford homopolymers with good solubility are desirable. However, the chemical structures of accessible cyclic KAEs are limited. Because the synthesis is based on intramolecular esterification, the precursors must have a suitable structure for cyclization. Compound 2a has a six-membered ring with a planar aromatic ring, whereas another example reported by Goto et al. has a five-membered ring with gem-dialkyl groups, subject to the Thorpe–Ingold effect [22, 23]. Salicylic acid can be prepared via the Kolbe–Schmit reaction of phenol, and its derivatives are commercially available. In this study, a series of cyclic KAEs with substituted aromatic rings were examined from the viewpoints of synthesis, stability, polymerization behavior, and polymer properties.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and stability of cyclic KAEs

The substitution of aromatic rings with alkoxy groups is a common strategy for improving the solubility of aromatic compounds. However, the introduction of an electron-donating alkoxy group increases the electron density in the vinylidene group, which increases the moisture sensitivity of cyclic KAEs. To evaluate the effect of the alkoxy substituent on the stability against moisture, the synthesis of methoxy derivative 2b was examined. Although acetylation progressed in high yield (93%; Scheme S1 and Fig. S1), intramolecular esterification did not afford the expected product 2b (Scheme 2). Instead, acetyl 4-methoxysalycylic acid (4b) was recovered (Fig. S2). As 2a was obtained in 73% yield using a similar procedure, the generation of 4b was attributed to the hydrolysis of 2b. Thus, 2b was unstable for isolation and underwent hydrolysis during purification. The acetoxy group, which is a weaker electron-donating group than the methoxy group, was subsequently investigated (Schemes S2 and S3). Although 2c and 2 d were isolated and characterized by 1H and 13C NMR (Figs. S4–S10), their yields were low (8.3%). Once isolated, 2c and 2 d were sufficiently stable in the solid state to be stored under an argon atmosphere in a refrigerator for at least one month.

Because substitution of the aromatic ring with electron-donating groups resulted in low yields, the use of alkyl groups with weaker electron-donating ability was investigated. Compound 2e, a cyclic KAE with two tert-butyl groups was obtained in moderate yield (55%). The molecular structures of the intermediates and 2e were confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy (Figs. S11–S13). To understand the effects of the two tert-butyl substituents on monomer stability, the hydrolysis of 2a and 2e under an air atmosphere was compared (Fig. 1). Although 2a could be stored under an argon atmosphere in a screw vial, allowing 2a powder to stand for 1 h in an open vial resulted in hydrolysis, affording 4a in 13% yield. After 3 d, 88% of 2a decomposed into 4a. The hydrolysis of 2e was slower than that of 2a, resulting in 13% and 52% yields of 4e after 6 h and 4 d, respectively. Therefore, substitution with two tert-butyl groups effectively increases the stability of the cyclic KAE owing to their hydrophobicity, although complete inhibition of hydrolysis was not achieved. Nevertheless, 2e was sufficiently stable to be weighed under atmospheric conditions for polymerization experiments and could also be stored in sealed vials.

Radical polymerization

Radical polymerization of 2 was conducted in bulk or in toluene at 65 °C using 2,2′-azoisobutyronitrile (AIBN) for 16 h (Scheme 3). In these polymerizations, monomers that did not participate in the polymerization underwent hydrolysis to afford 4, which was removed by washing the products with methanol for 2a–d and with diethyl ether (Et2O) for 2e. This purification process resulted in lower yields than expected. Compounds 2a, 2c, and 2e afforded the corresponding polymers via bulk polymerization (Table 1, Entries 1–3). P2c was soluble in DMF and chloroform (CHCl3). This was preferable to P2a, which was partly soluble in CHCl3 [9] and DMF [24]. Moreover, P2e exhibited good solubility in CHCl3, diethyl ether (Et2O), toluene, and tetrahydrofuran (THF), implying the positive effects of the tert-butyl substituents. Therefore, substitution of the aromatic ring was important for tuning the polymer solubility. Despite the success of the bulk polymerization of 2e (Entry 3), its solution polymerization did not afford a polymer (Entry 4), suggesting low reactivity. This was probably because the tert-butyl substituents increased the steric hindrance around the vinylidene group. The chemical structures of the obtained polymers were confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy (Figs. S14–17).

In our previous work, the relative reactivities of 2a (M1) and VAc (M2) in copolymerization with toluene were reported to be r1 = 1.51 and r2 = 0.587, respectively [9]. Similarly, the copolymerization of an equimolar mixture of 2a and VAc in bulk also afforded a polymer rich in 2a (Entry 5) [10]. This tendency was also observed in the copolymerization of 2c and VAc (Entry 6; Figs. S18 and S19). In contrast, the copolymerization of 2e with VAc afforded a polymer with a lower 2e content (Entry 7; Figs. S20 and S21). This result also implied that 2e had lower reactivity than 2a and 2c. To examine the relative reactivity of 2e, copolymerization with VAc was conducted at various feed ratios (F = [2e]/[VAc] = 0.12–0.83; Table S1), and the reactions were quenched before the monomer conversion exceeded 15%. The compositions were estimated from the feed ratio and conversion (f = [2e-unit]/[VAc-unit] = 0.054–0.41). Finally, the relative reactivities r1 and r2 were determined to be 0.703 and 2.21, respectively, using the Kelen–Tüdös method (Fig. 2), whereas the Q and e values were 0.00655 and −0.215, respectively. Although 2a and 2e had similar structures around the vinylidene groups, the Q and e values were significantly different (2a: Q = 0.13, e = −1.14. 2e: Q = 0.00655, e = −0.215). This implies a limitation of the Q-e scheme, which does not reflect steric effects. Nevertheless, the Q and e values of 2e are meaningful for describing its low reactivity.

The copolymerization of 2a (M1) and MMA (M2), which had relative reactivities of r1 = 0.0176 and r2 = 3.24, respectively, did not afford the 2a–2a homosequence (Entry 8) [10]. The absence of this homosequence was confirmed by the sharp aromatic signals in the 1H NMR spectrum, in contrast to the broad aromatic signal of P2a owing to the interaction from aromatic rings in neighboring units [10]. The copolymerization of 2e and MMA afforded similar results (Entry 9, Figs. S22 and S23), although the content of 2e units was lower than that of 2a units in Entry 8. Copolymerization with benzyl methacrylate (BnMA) afforded similar results (Entries 10 and 11; Figs. S24–S27).

The copolymerization of 2 with methacrylate monomers suggested the possibility of alternating the copolymerization of 2 and electron-poor vinyl monomers that scarcely homopolymerize. Therefore, the copolymerization of 2 with dimethyl maleate (DMM) was investigated. Copolymerization with 2a resulted in copolymers with a 58% 2a-unit content (Entry 12; Figs. S28 and S29). In fact, the time-versus-conversion plots suggested that the consumption of 2a was superior to that of DMM (Fig. 3A). The MALDI TOF-MS data (Fig. 3C) showed a characteristic splitting pattern consisting of a set of four peaks. The intervals between the most intense peaks (m/z 3334, 3496, 3640, and 3802) were 162, 144, and 162, respectively, suggesting an alternating chain of 2e and DMM units. However, the absolute m/z values indicated that these were not signals of a perfectly alternating copolymer. For example, the signal at 3496 was assigned to a polymer chain with a benzyl α-end generated by the chain-transfer reaction to toluene (Fig. 3E), twelve 2a-units, ten DMM-units, and an unsaturated ω-end owing to disproportionation termination (m/z: [M + Na]+ = 3497). For simplicity, this polymer chain, that is, a polymer consisting of twelve 2a-units and 10 DMM units, is denoted A12B10. Compared with the signal of A12B10, the signal of the alternating copolymer A11B11 (m/z: 3477) was slightly weaker. Signals corresponding to A13B9 (m/z: 3514) and A14B8 (m/z: 3353), which have excess 2a-units, were also observed. In other words, during the copolymerization of 2a and DMM, some 2a–2a sequences were formed. In contrast, the signals of A11B10 (m/z: 3334) and A11B12 (m/z: 3620) implied that the benzyl radical underwent an initiation reaction with both 2a and DMM. Importantly, the signal of A11B13 (m/z 3767; theoretical value) was not observed, suggesting the absence of DMM–DMM sequences. Therefore, the copolymerization of 2a with DMM produces an incomplete alternating copolymer containing 2a–2a sequences.

Because 2e is much less reactive than 2a is, the copolymerization of 2e was expected to proceed in an ideal alternating manner. In fact, copolymerization (Entry 13; Figs. S30 and S31) resulted in similar monomer consumption between 2e and DMM (Fig. 3B). The MALDI TOF-MS results revealed simpler signals than those obtained for copolymer 2a (Fig. 3D). Because there are two types of α-ends, the benzyl group and the AIBN fragment, the signals of the polymer with the AIBN fragment, such as A7B7*, are distinguished by an asterisk. A series of signals, A7B7*, A8B7*, A8B8*, and A9B8* (m/z: 3016, 3290, 3434, and 3708, respectively), suggested the formation of alternating chains. In these signals, the number of 2e units was the same or one greater than the number of DMM units, indicating that the radical generated from AIBN was selectively added to 2e. In contrast, signals of both A7B8 (m/z: 3183) and A8B7 (m/z: 3313) were observed next to the signal of A7B7 (m/z: 3039), indicating that the benzyl radical generated from toluene was added to both 2e and DMM. The next signal was A8B8 (m/z: 3457), confirming the alternating chains of 2e and DMM units. However, signals from polymer chains containing excess 2e units, such as A8B6, A9B6, and A9B7 (m/z: 3146, 3420, and 3564), were also observed. This suggests that 2e–2e sequences were also formed. Nevertheless, the copolymerization of 2e and DMM was closer to ideal alternating copolymerization than that of 2a.

Thermal properties

The obtained (co)polymers exhibited a 5% weight loss temperature (Td5) above 240 °C (Table 1; Figs. S32–S34). Thus, the substitution of the aromatic rings did not significantly affect the thermal degradation behavior of the polymers. We previously reported that the glass transition temperature (Tg) of P2a is 132 °C [10]. In contrast, P2e did not exhibit a glass transition until thermal decomposition was observed. To evaluate the effects of the two tert-butyl groups on the Tg, the copolymers of 2e and VAc were examined. The copolymers prepared for the Kelen–Tüdös plots (Table S1) were also analyzed. The Tg values of the copolymers containing 0–43 mol% 2e units occurred at 32–136 °C (Fig. S35) (Fig. 4). The higher Tg than that of the polymers of 2a was attributed to the substitution of the aromatic rings with two tert-butyl groups, causing steric hindrance that prevented bond rotation on the lactone rings. The copolymer with 20 mol% VAc units (Tg = 77 °C) afforded a transparent film upon hot pressing at 100 °C for 10 min under a pressure of 10 MPa; however, the film was brittle and could not be peeled off from the polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) sheet (Fig. S37). Similarly, a film of the homopolymer P2e was prepared by a casting method, but the obtained film was brittle, and many cracks formed (Fig. S38). These results were probably due to the rigidity of the polymer chains.

Conclusion

The synthesis and radical (co)polymerization of cyclic KAEs 2a–e derived from acetylsalicylic acid and its analogs with substituted aromatic rings were investigated. Substitution with electron-donating groups resulted in instability and low yields of KAEs. In contrast, 2e, which contains two tert-butyl groups on the aromatic ring, was more stable than 2a against moisture because of its hydrophobicity. The two bulky tert-butyl groups of 2e reduced the reactivity in radical polymerization; solution polymerization did not afford the homopolymer, whereas it was obtained in bulk polymerization. The reduced reactivity of 2e enabled effective copolymerization with DMM, resulting in an alternating copolymer consisting of almost ideal alternating sequences. The tert-butyl groups also significantly affected the solubility and Tg of the (co)polymers.

While examples of cyclic KAEs are limited, 2 has the advantages of the availability of raw materials and a facile synthetic procedure. This study revealed the effects of aromatic ring substituents on reactivity and polymer properties, which expands the potential of the molecular design of cyclic KAEs. We believe that this discovery will contribute to researcher interest in the polymer chemistry of cyclic KAEs.

References

Krause T, Baader S, Erb B, Gooßen LJ. Atom-economic catalytic amide synthesis from amines and carboxylic acids activated in situ with acetylenes. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11732.

Zeng L, Huang B, Shen Y, Cui S. Multicomponent synthesis of tetrahydroisoquinolines. Org Lett. 2018;20:3460–4.

Akai S, Naka T, Fujita T, Takebe Y, Kita Y, 1-Ethoxyvinyl 2-furoate, an efficient acyl donor for the lipase-catalyzed enantioselective desymmetrization of prochiral 2,2-disubstituted propane-1,3-diols and meso-1,2-diols. Chem Commun. 2000;36:1461–2.

Kita Y, Takebe Y, Murata K, Naka T, Akai S. Convenient enzymatic resolution of alcohols using highly reactive, nonharmful acyl donors, 1-ethoxyvinyl esters. J Org Chem. 2000;65:83–88.

Schudok M, Kretzschmar G. Enzyme catalyzed resolution of alcohols using ethoxyvinyl acetate. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:387–8.

Yin J, Bai Y, Mao M, Zhu G. Silver-catalyzed regio- and stereoselective addition of carboxylic acids to ynol ethers. J Org Chem. 2014;79:9179–85.

Wasserman HH, Wharton PS. 1-methoxyvinyl esters. I. preparation and properties. J Am Chem Soc. 1960;82:661–5.

Babin P, Bennetau B. 2-Alkylidene-benzo[1,3]dioxin-4-ones: a new class of compounds. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:5231–3.

Kazama A, Kohsaka Y. Radical polymerization of “dehydroaspirin” with the formation of a hemiacetal ester skeleton: a hint for recyclable vinyl polymers. Polym Chem. 2019;10:2764–8.

Kazama A, Kohsaka Y. Diverse chemically recyclable polymers obtained by cationic vinyl and ring-opening polymerizations of the cyclic ketene acetal ester “dehydroaspirin. Polym Chem. 2022;13:6484–91.

Boucher D, Laviéville S, Ladmiral V, Negrell C, Leclerc E. Hemiacetal esters: Synthesis, properties, and applications of a versatile functional group. Macromolecules. 2024;57:810–29.

Otsuka H, Endo T. Poly(hemiacetal ester)s: New class of polymers with thermally dissociative units in the main chain. Macromolecules. 1999;32:9059–61.

Otsuka H, Fujiwara H, Endo T. Fine-tuning of thermal dissociation temperature using copolymers with hemiacetal ester moieties in the side chain: effect of comonomer on dissociation temperature. React Funct Polym. 2001;46:293–8.

Otsuka H, Fujiwara H, Endo T. Thermal dissociation behavior of polymers with hemiacetal ester moieties in the side chain: The effect of structure on dissociation temperature. J Polym Sci A Polym Chem. 1999;37:4478–82.

Sato E, Yamanishi K, Inui T, Horibe H, Matsumoto A. Acetal-protected acrylic copolymers for dismantlable adhesives with spontaneous and complete removability. Polymer. 2015;64:260–7.

Kametani Y, Nakano M, Yamamoto T, Ouchi M, Sawamoto M. Cyclopolymerization of cleavable acrylate-vinyl ether divinyl monomer via nitroxide-mediated radical polymerization: Copolymer beyond reactivity ratio. ACS Macro Lett. 2017;6:754–7.

Kubota H, Ouchi M. Rapid and Selective Photo-degradation of Polymers: Design of an alternating copolymer with an O-nitrobenzyl ether pendant. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2023;62:e202217365.

Daito Y, Kojima R, Kusuyama N, Kohsaka Y, Ouchi M. Magnesium bromide (MgBr2) as a catalyst for living cationic polymerization and ring-expansion cationic polymerization. Polym Chem. 2021;12:702–10.

Kubota H, Yoshida S, Ouchi M. Ring-expansion cationic cyclopolymerization for the construction of cyclic cyclopolymers. Polym Chem. 2020;11:3964–71.

Neitzel AE, Petersen MA, Kokkoli E, Hillmyer MA. Divergent mechanistic avenues to an aliphatic polyesteracetal or polyester from a single cyclic esteracetal. ACS Macro Lett. 2014;3:1156–60.

Neitzel AE, Haversang TJ, Hillmyer MA. Organocatalytic cationic ring-opening polymerization of a cyclic hemiacetal ester. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2016;55:11747–55.

Oh XY, Ge Y, Goto A. Synthesis of degradable and chemically recyclable polymers using 4,4-disubstituted five-membered cyclic ketene hemiacetal ester (CKHE) monomers. Chem Sci. 2021;12:13546–56.

Er TKG, Lim XYH, Oh XY, Goto A. Synthesis of degradable homopolymer, gradient and block copolymers, and self-assembly via raft polymerization of 4,4-dimethyl-2-methylene-1,3-dioxolan-5-one. Macromolecules. 2024;57:8983–97.

Kohsaka Y, Kazama A, Matsuo K, Deguchi S, Osada M. Carbon-resource recovery from vinyl polymers of cyclic ketene acetal esters using high-temperature water. ACS Sustain Resour Manag. 2024;1:2234–40.

Kohsaka Y, Kawatani R, Nagasawa A, Hara S, Copolymers and coating agents. JP 2024124740A 2024.

Kohsaka Y, Kawatani R, Matsui S, Hara S, Nagasawa A, Copolymer and optical hard coat film. JP 2024124741A 2024.

Kohsaka Y, Toyama K, Kawauchi M, Naganuma K, Fast and selective main-chain scission of vinyl polymers using the domino reaction in the alternating sequence for transesterification. ACS Macro Lett. 2024;13:1016–21.

Mothe SR, Chennamaneni LR, Tan J, Lim FCH, Zhao W, Thoniyot PA. Mechanistic study on the hydrolysis of cyclic ketene acetal (CKA) and proof of concept of polymerization in water. Macromol Chem Phys. 2023;224:2300221.

Lena J-B, Van Herk AM. Toward biodegradable chain-growth polymers and polymer particles: Re-evaluation of reactivity ratios in copolymerization of vinyl monomers with cyclic ketene acetal using nonlinear regression with proper error analysis. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2019;58:20923–31.

Folini J, Murad W, Mehner F, Meier W, Gaitzsch J. Updating radical ring-opening polymerisation of cyclic ketene acetals from synthesis to degradation. Eur Polym J. 2020;134:109851.

Agarwal S. Chemistry, chances and limitations of the radical ring-opening polymerization of cyclic ketene acetals for the synthesis of degradable polyesters. Polym Chem. 2010;1:953–64.

Lai H, Ouchi M. Backbone-degradable polymers via radical copolymerizations of pentafluorophenyl methacrylate with cyclic ketene acetal: pendant modification and efficient degradation by alternating-rich sequence. ACS Macro Lett. 2021;10:1223–8.

Hill MR, Kubo T, Goodrich SL, Figg CA, Sumerlin BS. Alternating radical ring-opening polymerization of cyclic ketene acetals: access to tunable and functional polyester copolymers. Macromolecules. 2018;51:5079–84.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 23K23397 and 22H02129. Phthaloyl dichloride for the preparation of 1 was a kind gift from Iharanikkei Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. This work was supported (in part) by “Advanced Research Infrastructure for Materials and Nanotechnology in Japan (ARIM)” of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) under Grant JPMXP1224JI0039.

Funding

JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 23K23397, 22H02129 (for YK), and 21J12927 (for AK). Open Access funding partially provided by Shinshu University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft preparation. HT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. KA: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kohsaka, Y., Torisawa, H. & Kazama, A. Synthesis and polymerization of modified dehydroaspirin with increased stability and polymer solubility. Polym J 57, 1339–1346 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-025-01070-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-025-01070-4