Abstract

Interest in environmental problems is increasing worldwide. Among these issues, microplastics—microscaled plastics formed from plastic waste—are emerging as a serious threat. Various animals in the ocean and other environments are affected by microplastics. In this work, we develop a decomposable and recyclable polymeric material using polystyrene with trithiocarbonate substituents in its chemical structure to remove plastic waste and address the environmental problems associated with plastics. This polymeric material can be decomposed by reaction with allylamine at room temperature and crumbles 96 h after allylamine is poured on it. Moreover, the decomposed polymer is recyclable via a thiol-ene reaction with UV irradiation (λ = 365 nm, 6 h).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

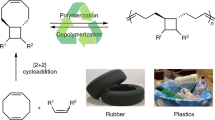

Today, interest in environmental problems has increased because global warming and environmental pollution by chemicals are becoming serious [1,2,3]. Among environmental problems, pollution by plastic waste is a crucial problem that needs to be solved urgently. A substantial amount of plastic waste is generated every day and is present in cities, forests, and mountains [4,5,6]. This plastic waste can cause conflagration and unsanitary conditions. On the other hand, microplastics have harmful effects on marine organisms, as this pollutant can block their organs, respiratory systems, and digestive systems [7,8,9]. In addition, the natural sources, such as petroleum, used for making plastics are limited and need to be used efficiently [10, 11]. The development of decomposable materials and recyclable materials may help solve plastic pollution problems and address the limitations of natural sources, e.g., petroleum. In this context, the decomposition and recycling mechanisms of plastics have been thoroughly researched [12, 13]. Additionally, various decomposable or recyclable materials are needed and are being reported [14,15,16,17,18,19]. Plastics are mainly recycled with two types of recycling systems, i.e., mechanical recycling systems [20,21,22] and chemical recycling systems [23,24,25,26], with the exception of energy recycling, in which plastics are used for fuels.

Mechanical recycling systems are less expensive and do not need a catalyst. The materials are decomposed by mechanical forces and used again as recycled plastics. In this way, mechanical recycling systems are simple and do not need further recycling processes. However, unneeded components need to be removed from the used plastics before they are recycled, imposing an additional cost on mechanical recycling systems. Chemical recycling systems need more energy than mechanical recycling systems do. However, it is easier for chemical recycling systems to separate unneeded components from materials than for mechanical recycling systems. For example, in chemical recycling systems, acrylic polymers can be decomposed to monomers by heating at an appropriate temperature (pyrolysis) [27]. The resultant monomers can be used for synthesizing recycled acrylic polymers. In this way, acrylic polymers can be recycled by pyrolysis. Chemical recycling systems decompose plastics into monomers by heating them at appropriate temperatures with or without inorganic catalysis. Compared with mechanical recycling systems, it is rather easier to remove unwanted materials during recycling. For chemical recycling systems, lowering the energy required to decompose materials and simplifying the recycling protocols is important.

In this work, we report a decomposable and recyclable material using a polymer with multiple trithiocarbonate substituents. Trithiocarbonate groups are often used for reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization, which is a common type of living radical polymerization [28,29,30,31]. RAFT polymerization is used for synthesizing topological polymers [32,33,34] with complicated chemical structures, such as block copolymers, or with low polymeric dispersity when dormant species are being used, because the determination reaction rarely takes place during RAFT polymerization by the formation of dormant species. Moreover, some polymeric materials containing RAFT reagents have been reported as functional polymeric materials, such as self-healing materials [35,36,37].

In this work, we synthesized polystyrene with multiple trithiocarbonate substituents via RAFT polymerization using a RAFT polymer and evaluated its decomposition at room temperature and its recycling properties.

Experimental

Materials

Carbon disulfide (CS2) and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) were purchased from KANTO Chemical Co., Inc. 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]-7-undecene, 2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (DMPA), allylamine, 2,2’-azobis(isobutyronitrile) (AIBN), and benzylamine were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. Acrylamide (AAm) and N,N’-methylenebis(acrylamide) (MBAm) were purchased from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation. All other chemicals were purchased from KANTO Chemical Co., Inc., and used as received.

Characterization and measurements

1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Model 500-MR spectrometer. Cross-polarization magic angle spinning with total suppression of sidebands (CPMAS_TOSS) (NMR) and CPMAS with polarization inversion with total suppression of sidebands (CPPI_TOSS) (NMR) were measured with a JEOL JNM-ECZ600II. An indentation test was performed using an Imada MX2-500N-FA equipped with an Imada ZTA-50N. The samples were 10 mm (height) × 10 mm (width) × 2 mm (thickness). The rate of indentation was 30 mm/min. Infrared (IR) spectroscopy was conducted using a JASCO FT/IR-4100. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were recorded using a JEOL JCM-5610LV scanning electron microscope. SEM samples were spin-coated with platinum using an ion sputter coater (Hitachi E-1030 Ion Sputter Coater). EDX data were obtained by using EMAX-5770 (Horiba Ltd.) attached to a JCM-5610LV SEM instrument. Absorption spectra were measured using a Hitachi High-Tech Corporation U-2900. The optical path length of absorption spectroscopy was 10 mm. Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) was conducted using a JASCO LC-2000Plus series gel permeation chromatography system (JASCO Corporation). DMF was used as the eluent for GPC.

Synthesis of the TTC oligomer

1,4-Bis(chloromethyl)benzene (4.4 g, 25 mmol) was dissolved in 15 mL of chloroform. The solution was mixed with a chloroform solution of CS2 (3.8 g, 50 mmol) and potassium carbonate (K2CO3, 6.9 g, 50 mmol) and heated at 40 °C for 24 h. The resulting solution was poured into acetone, and a yellow precipitate formed. The precipitate was collected by filtration and dried in vacuo. Consequently, the TTC oligomer was obtained as a yellow powder and estimated by solid-state NMR spectroscopy (CPMAS_TOSS and CPPI_TOSS 13C NMR), as shown in Figs. S1 and S2. The yield of the TTC oligomer was 4.3 g.

Synthesis of the RAFT polymer

The synthesized TTC oligomer (25 mg, 120 μmol) was mixed with styrene (2.3 mL, 20 mmol) and AIBN (1.6 mg, 10 mmol) in 1.0 mL of DMF. The solution was stirred for 20 h at 100 °C after N2 gas was bubbled into the solution. The resulting solvent and other monomers were evaporated in vacuo. Consequently, the RAFT polymer was obtained as a yellow powder and was estimated by 1H NMR spectroscopy, as shown in Fig. S3.

Synthesis of polystyrene

Styrene (20 mmol) was dissolved in 1.0 mL of DMF, mixed with the radical initiator AIBN (10 μmol), and heated at 100 °C for 20 h with stirring after N2 gas was bubbled into the solution. The resulting solvent and other monomers were evaporated in vacuo. Finally, polystyrene was obtained as a white powder. The powder obtained was analyzed by 1H NMR spectroscopy, as shown in Fig. S4.

Synthesis of MBTTC

4-Methylbenzylchloride (0.71 g, 5.0 mmol) was mixed with potassium carbonate (0.79 g, 10 mmol) and carbon disulfide (1.4 g, 10 mmol) in 5 mL of chloroform. The solution was stirred at 40 °C for 24 h and then poured into 40 mL of ice water. The solution was extracted with ethyl acetate, and the organic layer was dried with magnesium sulfate anhydrate. The solution was filtered, and the filtrate was dried in vacuo to obtain MBTTC. The precipitate was estimated by 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectroscopy, as shown in Figs. S5 and S6. The yield of MBTTC was 0.55 g (69%).

Decomposition of the RAFT polymer using allylamine

The RAFT polymer was mixed with allylamine at room temperature. After 96 h, the decomposition of the RAFT polymer was confirmed from the perspective of mechanical strength. Additionally, the decomposition by allylamine was evaluated by using gel permeation chromatography (GPC), as shown in Fig. S7. RAFT polymer (50 mg) and 100 μL of allylamine were mixed for 30 min and dried in vacuo. The resulting decomposed RAFT polymer and original RAFT polymer were used for GPC measurements. While the molecular weight of the original RAFT polymer calculated from the GPC chart was 3.7 × 105, the peak of the molecular weight of the RAFT polymer appeared at 1.9 × 105 after the addition of 3.7 × 105 allylamine for 30 min. The RAFT polymer underwent chain shortening because of the reaction between the trithiocarbonates of the RAFT polymer and allylamine.

Recycling of the RAFT polymer

The polymer decomposed by allylamine was recycled by a thiol-ene reaction between the amine and allyl substituents. The decomposed RAFT polymer was mixed with a 19.5 mM chloroform solution of DMPA, which is a radical initiator, and exposed to UV light (λ = 365 nm, 6 h).

Results and discussion

Decomposition and recycling test

First, an oligomer with multiple trithiocarbonate substituents in its structure (TTC oligomer), as shown in Scheme 1, was synthesized according to the experimental procedure.

The synthesized TTC oligomer, styrene, and AIBN were mixed in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and heated at 100 °C for 20 h. After the reaction, the solvent was evaporated in vacuo, and a yellow polymer was obtained as the RAFT polymer, as shown in Fig. 1a. The RAFT polymer was used for the decomposition and recycling experiments shown in Fig. 1b.

a Chemical structure of the RAFT polymer and a photograph of the RAFT polymer shaped with a mold. b Schematic illustrations and photographs of the RAFT polymer after decomposition with allylamine and recycling by UV irradiation (λ = 365 nm, 6 h). Photographs of the recycled RAFT polymer were taken directly above and in the vertical direction

The RAFT polymer was shaped like a mold whose shape is a two-beamed eighth note, as shown in Fig. 1b. A chloroform solution of the RAFT polymer was poured into the mold and dried in vacuo. The resulting molded RAFT polymer was a yellowish transparent organic glass with high mechanical strength, as it could be picked up with a pair of tweezers without being broken. Next, allylamine was applied to the surface of the molded RAFT polymer. After that, the molded RAFT polymer became cloudy and decomposed at room temperature. The decomposed RAFT polymer could not be picked up with a pair of tweezers and was broken. This suggests that the RAFT polymer was decomposed by the reaction with allylamine shown in Scheme 2. On the other hand, the molded polystyrene, which did not contain trithiocarbonate groups, as shown in Fig. S4, was not decomposed by the addition of allylamine. Even after allylamine was applied to the surface, the strength of the molded polystyrene was as high as that of the original polystyrene and could be picked up with a pair of tweezers, as shown in Fig. S8. These results also indicate that the trithiocarbonate substituents in the RAFT polymer were decomposed by the reaction with allylamine, as shown in Scheme 2.

Next, the RAFT polymer decomposed with allylamine was recycled by a thiol-ene reaction [38,39,40] using DMPA, which is a photo-radical initiator, via UV irradiation (λ = 365 nm). The decomposed RAFT polymer was mixed with DMPA and inserted into a mold in the shape of an eighth note. After insertion, the mixture was irradiated with UV light (λ = 365 nm, 6 h). Consequently, the decomposed RAFT polymer reconstructed a new molded polymeric material, as shown in Fig. 1b. This result suggests that the decomposed RAFT polymer was joined mainly by thioether bonds via the thiol-ene reaction and formed a cross-linked polymer via thioether bonds, as shown in Scheme 3.

SEM of the samples

The morphology of all the RAFT polymers before and after decomposition by allylamine and after recycling via thiol-ene reactions was observed by SEM, as shown in Fig. 2. Although pores caused by the evaporation of solvent were observed, the surfaces of the RAFT polymer and polystyrene were smooth before the addition of allylamine, as shown in Fig. 2a. On the other hand, the surface of the RAFT polymer became rough, while the polystyrene remained smooth after the addition of allylamine, as shown in Fig. 2b and S9. This difference between the RAFT polymer and polystyrene was likely due to the decomposition of trithiocarbonate by the reaction with allylamine. The rough surface of the RAFT polymer decomposed by allylamine became smooth again after the thiol-ene reaction via UV irradiation (λ = 365 nm), as shown in Fig. 2c. This change was presumably due to the formation of long polymer chains again after the thiol-ene reaction. The SEM images support the hypothesis that the RAFT polymer can be decomposed and recycled by reactions with allylamine and thiol-ene, respectively. Energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectra were obtained simultaneously with SEM observations, as shown in Fig. S10. The elemental ratio of nitrogen of the RAFT polymer calculated with EDX was 1.1 wt%, which is due to the air absorbed by the SEM sample of the RAFT polymer, whereas that of the RAFT polymer after recycling was 2.4 wt%. The percentage of nitrogen increased by 1.3 wt% after decomposition and recycling. Allylamine was assumed to have been incorporated into the RAFT polymer by a decomposition and recycling reaction.

SEM images of a the RAFT polymer, b the RAFT polymer decomposed by allylamine, and c the RAFT polymer recycled by UV irradiation (λ = 365 nm). Photographs of the polymers are shown in Fig. 1. The pores at the surface of the RAFT polymer were presumably caused by the evaporation of the solvent

Absorption spectroscopy

The RAFT polymer was dissolved in chloroform (0.6 wt%) and mixed with allylamine (280 mM). After mixing, the time-course changes in the appearance and absorption spectra of the solution were observed and measured, as shown in Fig. 3. The color of the solution shown in Fig. 3a diminished as time passed after mixing with allylamine. This change in appearance was likely due to the decomposition of trithiocarbonate substituents in the RAFT polymer. Additionally, the time-course change in the absorption spectra indicated the decomposition of trithiocarbonate substituents, as shown in Fig. 3b. The absorption band assigned to the trithiocarbonate substituents at approximately 314 nm decreased as time passed after mixing with the RAFT polymer owing to the disruption of the trithiocarbonate substituents.

a Schematic illustration of the decomposition of the RAFT polymer by allylamine and a time-course photograph of the RAFT polymer (0.6 wt%) mixed with allylamine (280 mM) in chloroform. b Time-course change in the absorption spectra of the RAFT polymer (0.6 wt%) mixed with allylamine (280 mM) in chloroform at room temperature (0–3 h)

Mechanical strength of the RAFT polymer before and after the decomposition and recycling processes

The mechanical strength of the organic glasses, which consisted of the original RAFT polymer, was measured by an indentation test, as shown in Fig. 4 and S11. The average breaking stress of the three original RAFT polymers and its standard deviation was 651 ± 168 N m−1. After the decomposition by allylamine, the average breaking stress of the RAFT polymer and its standard deviation decreased to 37 ± 15 N m−1. The breaking stress of the RAFT polymer decreased to 5.7% of that of the original RAFT polymer. Additionally, the breaking stress of the sample decreased drastically after decomposition, as shown in Fig. S10. On the other hand, the average breaking stress of the RAFT polymer and its one deviation recovered to 869 ± 197 N m−1 after recycling with UV irradiation (λ = 365 nm). The results of the indentation test indicate that the mechanical strength can be recovered by recycling the RAFT polymer via a thiol-ene reaction. In contrast, the mechanical strength of the polystyrene on which allylamine was not applied did not change, as shown in Fig. S12. This suggests that the polystyrene did not decompose because it has no trithiocarbonate groups reacting with amines in its structure.

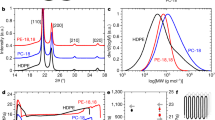

IR spectroscopy

The progress of the decomposition and recycling reactions with allylamine and subsequent thiol-ene reactions was investigated by IR spectroscopy, as shown in Fig. 5. The IR band of MBTTC, as a model compound of the RAFT polymer at 1062 cm−1, assigned to the C=S bond of trithiocarbonates, decreased significantly after the reaction with allylamine. On the other hand, the band assigned to the C=C bond of allyl substituents appeared as a shoulder band at approximately 1510 cm−1, and the band assigned to C=S bonded to nitrogen appeared at 1644 cm−1. After the thiol-ene reaction, the specific absorption band assigned to the C=C bond of allyl substituents at approximately 1510 cm−1 disappeared. These changes in the IR spectra were presumably caused by the thiol-ene reaction between the allyl substituents and thiol substituents.

NMR spectroscopy

The progress of the decomposition and recycling reactions was confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy using a model compound (MBTTC) of the RAFT polymer, as shown in Figs. 6 and 7. The proton signals assigned to the protons of MBTTC at 4.58 ppm decreased as time passed since it was mixed with allylamine, as shown in Fig. 7. The time-course change in the intensity of MBTTC is summarized in Fig. 8. After 96 h, the proton signals of MBTTC disappeared completely.

Decomposition rate calculated from the signal intensities obtained from the 1H NMR spectra of MBTTC, shown in Fig. 6. a Scheme of the decomposition reaction of MBTTC by mixing with allylamine. b Time-course change in signal intensity assigned to the protons highlighted in green in (a)

In the same manner, the decomposed RAFT polymer is bonded via a thiol-ene reaction triggered by UV irradiation (λ = 365 nm), as shown in Fig. 8. As the thiol-ene reaction progressed, the NMR signals assigned to the allyl protons disappeared, and the signals assigned to the decomposed structure appeared as time passed. The decomposition ratio was calculated using the intensities of the signal assigned to the allyl groups of MBTTC in the figure. As shown in Fig. 8, the reaction progressed to near completion in 96 h. These changes in the NMR spectra indicated the progress of the thiol-ene reaction between allyl substituents and thiol substituents.

When benzylamine was used instead of allylamine for decomposition, the RAFT polymer was decomposed by the reaction with benzylamine, as shown in Scheme S1 and Figs. S13 and S14. The decomposition by benzylamine was confirmed in the same manner as that by allylamine, as shown in Fig. S15a. The mechanical strength of the RAFT polymer decreased after benzylamine was applied to the RAFT polymer, similar to the results using allylamine. However, the decomposed RAFT polymer did not reconstruct a polymer material, and its mechanical strength did not recover even after UV irradiation (λ = 365 nm), as shown in Fig. S15b. The decomposed RAFT polymer could not form long polymer chains and did not form a polymeric material using benzylamine instead of allylamine because benzylamine does not have an allyl substituent in its structure. This result confirmed that the recycling ability can be regulated by the chemical structure of the amine molecules used for the decomposition of the RAFT polymer.

Conclusion

In this work, we report a decomposable and recyclable polystyrene with trithiocarbonate substituents. The materials decomposed because of a decomposition reaction with allylamine. After 96 h, the molded RAFT polymer was decomposed by the application of allylamine to the polymer. The average breaking stress of the decomposed RAFT polymer is only 5.7% greater than that of the original polymer. Moreover, the decomposed polymer could be recycled using a thiol-ene reaction between the decomposed termini of the polymer by shining UV light (λ = 365 nm) on the decomposed polymer for 6 h. The mechanical strength of the recycled polymer (869 ± 197 N m−1) was as high as that of the original polymer (651 ± 168 N m−1). Usually, polystyrene is chemically decomposed to a monomer (styrene) by heating and recycling. Thus, the general chemical recycling of polystyrene requires a considerable amount of energy. In this work, the material composed of polystyrene does not need reheating and can be recycled at room temperature.

Moreover, this decomposable and recyclable system can be applied to create other polymer materials that are reactive toward RAFT polymerization using trithiocarbonates, such as acrylic polymers.

The decomposable and recyclable material using trithiocarbonates and their reaction with amines, as reported in this research, is expected to contribute to the development of eco-friendly materials that, in the future, can reduce the consumption of fuel and prevent the accumulation of plastic pollution in the oceans and other natural environments.

References

Kampa M, Castanas E. Human health effects of air pollution. Environ Pollut. 2008;151:362–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.012.

Eriksen M, Mason S, Wilson S, Box C, Zellers A, Edwards W, et al. Microplastic pollution in the surface waters of the Laurentian Great Lakes. Mar Pollut Bull. 2013;77:177–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.10.007.

Lelieveld J, Evans JS, Fnais M, Giannadaki D, Pozzer A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature. 2015;525:367–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15371.

Rochman CM, Browne MA, Halpern BS, Hentschel BT, Hoh E, Karapanagioti HK, et al. Classify plastic waste as hazardous. Nature. 2013;494:169–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/494169a.

Jambeck JR, Geyer R, Wilcox C, Siegler TR, Perryman M, Andrady A, et al. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science. 2015;347:768–71. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260352.

Law KL, Starr N, Siegler TR, Jambeck JR, Mallos NJ, Leonard GH. The United States’ contribution of plastic waste to land and ocean. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eabd0288. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd0288.

Cole M, Lindeque P, Fileman E, Halsband C, Goodhead R, Moger J, et al. Microplastic ingestion by Zooplankton. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:6646–55. https://doi.org/10.1021/es400663f.

Hidalgo-Ruz V, Gutow L, Thompson RC, Thiel M. Microplastics in the marine environment: a review of the methods used for identification and quantification. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:3060–75. https://doi.org/10.1021/es2031505.

Amelia TSM, Khalik WMAWM, Ong MC, Shao YT, Pan HJ, Bhubalan K. Marine microplastics as vectors of major ocean pollutants and its hazards to the marine ecosystem and humans. Prog Earth Planet Sci. 2021;8:12 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-020-00405-4.

Hahn-Hägerdal B, Galbe M, Gorwa-Grauslund MF, Lidén G, Zacchi G. Bio-ethanol – the fuel of tomorrow from the residues of today. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24:549–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.10.004.

Prasad S, Singh A, Joshi HC. Ethanol as an alternative fuel from agricultural, industrial and urban residues. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2007;50:1–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2006.05.007.

Yang Y, Boom R, Irion B, Van Heerden DJ, Kuiper P, De Wit H. Recycling of composite materials. Chemical Eng Process Process Intensif. 2012;51:53–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cep.2011.09.007.

Hopewell J, Dvorak R, Kosior E. Plastics recycling: challenges and opportunities. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2009;364:2115–26. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0311.

Schneiderman DK, Hillmyer MA. 50th anniversary perspective: there is a great future in sustainable polymers. Macromolecules. 2017;50:3733–49. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.macromol.7b00293.

Fortman DJ, Brutman JP, De Hoe GX, Snyder RL, Dichtel WR, Hillmyer MA. Approaches to sustainable and continually recyclable cross-linked polymers. ACS Sus Chem Eng. 2018;6:11145–59. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b02355.

Rosenboom JG, Langer R, Traverso G. Bioplastics for a circular economy. Nat Rev Mater. 2022;7:117–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-021-00407-8.

Zhu Y, Romain C, Williams CK. Sustainable polymers from renewable resources. Nature. 2016;540:354–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21001.

Zhang Y, Broekhuis AA, Picchioni F. Thermally self-healing polymeric materials: the next step to recycling thermoset polymers?. Macromolecules. 2009;42:1906–12. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma8027672.

Denissen W, Winne JM, Du Prez FE. Vitrimers: permanent organic networks with glass-like fluidity. Chem Sci. 2016;7:30–38. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5SC02223A.

Vollmer I, Jenks MJF, Roelands MCP, White RJ, Van Harmelen T, De Wild P, et al. Beyond mechanical recycling: giving new life to plastic waste. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2020;59:15402–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201915651.

Cui J, Forssberg E. Mechanical recycling of waste electric and electronic equipment: a review. J Hazard Mater. 2003;99:243–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3894(03)00061-X.

Gu F, Guo J, Zhang W, Summers PA, Hall P. From waste plastics to industrial raw materials: a life cycle assessment of mechanical plastic recycling practice based on a real-world case study. Sci Total Environ. 2017;601-602:1192–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.278.

Yang R, Xu G, Dong B, Hou H, Wang Q. A “polymer to polymer” chemical recycling of PLA plastics by the “DE–RE polymerization” strategy. Macromolecules. 2022;55:1726–35. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.macromol.1c02085.

Paszun D, Spychaj T. Chemical recycling of poly(ethylene terephthalate). Ind Eng Chem Res. 1997;36:1373–83. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie960563c.

Sasse F, Emig G. Chemical recycling of polymer materials. Chem Eng Technol. 1998;21:777–89. 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4125(199810)21:10<777::AID-CEAT777>3.0.CO;2-L.

Thiounn T, Smith RC. Advances and approaches for chemical recycling of plastic waste. J Polym Sci. 2020;58:1347–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/pol.20190261.

Lattimer RP. Pyrolysis mass spectrometry of acrylic acid polymers. J Anal Appl Pyrol. 2003;68-69:3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-2370(03)00080-9.

Boyer C, Bulmus V, Davis TP, Ladmiral V, Liu J, Perrier S. Bioapplications of RAFT polymerization. Chem Rev. 2009;109:5402–36. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr9001403.

Chiefari J, Chong YK(Bill), Ercole F, Krstina J, Jeffery J, Le TPT, et al. Living free-radical polymerization by reversible addition−fragmentation chain transfer: the RAFT process. Macromolecules. 1998;31:5559–62. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma9804951.

Moad G, Rizzardo E, Thang SH. Living radical polymerization by the RAFT process. Aust J Chem. 2005;58:379 https://doi.org/10.1071/CH05072.

Perrier S, Takolpuckdee P. Macromolecular design via reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT)/xanthates (MADIX) polymerization. J Polym Sci A Polym Chem. 2005;43:5347–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/pola.20986.

Lai JT, Filla D, Shea R. Functional polymers from novel carboxyl-terminated trithiocarbonates as highly efficient RAFT agents. Macromolecules. 2002;35:6754–6. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma020362m.

Warren NJ, Armes SP. Polymerization-induced self-assembly of block copolymer nano-objects via RAFT aqueous dispersion polymerization. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:10174–85. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja502843f.

Mitsukami Y, Donovan MS, Lowe AB, McCormick CL. Water-soluble polymers. 81. Direct synthesis of hydrophilic styrenic-based homopolymers and block copolymers in aqueous solution via RAFT. Macromolecules. 2001;34:2248–56. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma0018087.

Ida S, Kimura R, Tanimoto S, Hirokawa Y. End-crosslinking of controlled telechelic poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) toward a homogeneous gel network with photo-induced self-healing. Polym J. 2017;49:237–43. https://doi.org/10.1038/pj.2016.112.

Rigby ADM, Alipio AR, Chiaradia V, Arno MC. Self-healing hydrogel scaffolds through PET-RAFT polymerization in cellular environment. Biomacromolecules. 2023;24:3370–9. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.3c00431.

Ueno Y, Nakazaki H, Onozaki H, Tamesue S. Adhesive gel system growable by reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization. ACS Appl Polym Mater. 2023;5:983–90. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsapm.2c01913.

Jonkheijm P, Weinrich D, Köhn M, Engelkamp H, Christianen PCM, Kuhlmann J, et al. Photochemical surface patterning by the thiol-ene reaction. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:4421–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200800101.

Hoyle CE, Bowman CN. Thiol-ene click chemistry. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:1540–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200903924.

Sinha AK, Equbal D. Thiol−ene reaction: synthetic aspects and mechanistic studies of an anti-markovnikov-selective hydrothiolation of olefins. Asian J Org Chem. 2019;8:32–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajoc.201800639.

Acknowledgements

The Supporting Information is available free of charge. We thank Mr. Makoto Roppongi, Utsunomiya University, for his technical assistance. The CPMAS_TOSS and CPPI_TOSS NMR measurements were supported by the Equipment Sharing Division, Organization for Co-Creation Research and Social Contributions, Nagoya Institute of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was written through the contributions of all the authors. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Onozaki, H., Dan Phuong, H.N., Maruoka, S. et al. Design of a decomposable and recyclable polymeric material via oligo(trithiocarbonate) and its chemical reaction with allylamine. Polym J 58, 69–78 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-025-01103-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-025-01103-y