Abstract

Synthetic polymers, such as plastics, are ubiquitous materials that are used in many applications. The sustainable use of plastics is becoming increasingly important given the emergent issues of environmental pollution by microplastics and the limited petroleum resources on Earth. One of the key strategies for the sustainable use of plastics is recycling. Enzymatic degradation is a promising technique for recycling plastic because this process requires neither energy nor harsh solvents, such as strong alkaline solutions and organic solvents. In this study, the enzymatic degradation of poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET), a major plastic used in daily life, was investigated to improve the efficiency of enzymatic degradation by understanding the decay of the polymeric PET structure. The structural decay of an amorphous PET film induced by a PET-hydrolyzing enzyme (PETase) was analyzed using wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD), small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), electron microscopy, and X-ray computed tomography (X-ray CT). Structural decay progressed from the surface of the film, and many nested pores (10–8–10–5 m) were found in the later stage of degradation, reflecting the structural difference between the surface and core of the material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Synthetic polymers and plastics are important materials in our daily lives. Massive amounts of plastics are produced from petroleum, which is a limited resource. Accordingly, securing a supply of raw materials that can replace petroleum or naphtha is becoming increasingly important for sustainable life. Another issue associated with the use of plastics is environmental pollution. Ocean plastics are major environmental pollutants and create social issues owing to their significant threat to marine organisms [1]. The impact on human health has also been debated [2]. Therefore, conserving natural resources and reducing the emission of environmental pollutants are important for the sustainable use of plastics in the future.

Thus, a circular plastic economy must be realized [3, 4] to secure raw materials for regenerating plastics and reduce the leakage of plastics into the environment. Poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) is a popular plastic that is widely used in food packaging, including drink bottles and cost-effective clothing, and it is one of the significant plastics that invokes environmental pollution, as shown by previous studies; for example, PET was the most dominant microplastic from sea surface sediment and water samples in Yamaguchi Bay and Doigahama Beach in Japan [5]. Additionally, after polyethylene and polypropylene, PET is the third most common marine plastic waste on the deep sea floor in Sagami Bay (adjacent to highly populated areas of Japan) [6] and plastic waste in river waters across Japan [7]. A similar situation is also expected in other water areas [8, 9].

There are two types of PET recycling systems: mechanical and chemical [10]. In the mechanical recycling of PET, PET products such as drink bottles are reshaped by heating after fragmentation into flakes. This process is relatively simple and is the primary method for recycling PET. However, the process of mechanically crushing the material into smaller flakes for efficient thermal reshaping is a potential origin of microplastics in the environment and a possible issue in achieving a highly sustainable society with plastics. In contrast, for chemical recycling, the used PET material is first disintegrated into monomers or oligomers via chemical reactions. The obtained monomers and oligomers are recovered and polymerized to regenerate PET. This process can maximize recycling efficiency because it can be applied to various materials (colored bottles, yarns, textiles, films, etc.). However, this process is costly because of the energy and chemicals required to disintegrate the used PET materials and recover the monomers and oligomers.

Recently, enzymatic degradation has attracted considerable attention as an efficient tool for disintegrating PET materials under mild conditions for chemical recycling. After the initial discovery of a PET-hydrolyzing enzyme in the biomass-degrading bacterium Thermobifida fusca [11], many studies using life-science strategies have reported PET-hydrolyzing enzymes, hereafter called PETase, based on bacterial screening [12], metagenomic screening [13], and rational design by site-directed mutagenesis [14, 15]. The mechanism of the enzymatic hydrolysis of PET molecules is well debated and deeply understood [16,17,18]. These studies have provided impetus for improving the enzymatic activity of PETase using life-science strategies; however, only basic characterizations, such as analyses of weight loss, surface morphology, and crystallinity using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), have been performed [12, 14], and little attention has been given to the decay of the higher structures of PET by PETase.

Given the current situation, the authors propose that the structure of PET materials is an important factor that governs the enzymatic degradability and properties of PET; thus, an in-depth analysis of the structural changes of PET materials during degradation by PETase is warranted. In this study, a multiscale analysis of the structural decay of an amorphous PET film by PETase was conducted by machine learning using Fast-PETase [14] as a model enzyme, which is an improved variant of IsPETase from the bacterium Ideonera sakaiensis (discovered at a PET bottle recycling site) [12]. The model PET substrate used in this study is a laboratory-made amorphous film that has been intensively analyzed in the field of polymer science [19,20,21]. Using this experimental setup, this study aims to clarify how PETase disintegrates the polymer structure of PET.

Materials and methods

All chemicals used in this study were purchased from Fujifilm Wako Chemicals (Tokyo, Japan), Nacalai Tesque Inc. (Kyoto, Japan), and Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA), unless otherwise indicated. Tryptone and yeast extracts for the bacterial cultures were purchased from Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Imidazole for protein purification was purchased from Calbiochem, Inc. (Rahway, NJ, USA).

Preparation of PET substrate

PET pellets were purchased from Scientific Polymer Products, Inc. (NY, USA; catalog #: 138; inherent viscosity: 0.58) and subjected to melt-quenching to prepare amorphous PET films. First, approximately 60 mg of the PET pellets were sandwiched between a pair comprising Kapton film, glass slides, and copper plates; the Kapton film touched the PET pellets directly, and the copper plates exposed to the outside were used for efficient heat transfer. This sandwich was placed on a heating plate and maintained at 300 °C for ca. 2 min and manually pressed with forceps to remove visible air bubbles. Thereafter, the PET in the Kapton film was quickly placed between the copper plates at room temperature (ca. 20 °C), which is lower than the glass transition temperature of PET (ca. 75 °C). This melt-quenched amorphous film, which typically had a thickness of 150 µm and a round shape with a radius of 10 mm, was evenly cut with scissors into 8 fan-shaped pieces and used as the substrate in the degradation experiment.

Purification of PETase

Cloning of fast-PETase

The PETase used in this study is a previously reported Fast-PETase [14], which is a highly thermostable variant of IsPETase. The first 27 amino acid residues were truncated as previously described [14] because this region was predicted to be a signal peptide by SignalP6.0 [22]. The DNA sequence of Fast-PETase without the signal peptide sequence was synthesized by Eurofins Genomics Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) with codon optimization in Escherichia coli. The DNA of the codon-optimized Fast-PETase gene was inserted between the NdeI and BamHI sites in the cloning site of the pET-28b plasmid (Millipore Inc.) by restriction enzyme treatment and subsequent ligation.

Expression of recombinant PETase protein in Escherichia coli

The pET-28b plasmid carrying Fast-PETase, prepared as described in Section “ Cloning of Fast-PETase”, was introduced into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). The E. coli transformants carrying this plasmid DNA were selected on LB agar plates on the basis of kanamycin resistance and used to express recombinant Fast-PETase protein.

The transformant was precultured in LB liquid medium with 50 μg/mL kanamycin at 37 °C with orbital shaking at 200 rpm. In a typical experiment, 0.5 mL of the preculture was transferred into 50 mL of fresh 2× YT medium with 25 μg/mL kanamycin in a 300 mL flask without baffles. The flask was maintained at 37 °C in an orbital shaker with agitation at 200 rpm until the OD600 reached 0.6‒0.8, after which isopropyl thio-β-d-galactoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM to induce protein expression. The culture was then maintained at 20 °C for ca. 20 h in an orbital shaker at 200 rpm. Finally, the cultured E. coli cells were collected by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C and kept in a freezer at −80 °C until use.

The frozen cells were thawed on ice and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 5–10 mM imidazole. The cell suspension was ultrasonicated to disrupt the cells and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to remove the unbroken cells, and the supernatant was filtered using Miracloth (Merck Inc.). Hexahistidine-tagged Fast-PETase in the clarified lysate was purified using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC). Ni-Sepharose (Cytiva, Inc., Marlborough, MA, US) was placed in a plastic column (Poly-Prep column; Bio-Rad, Inc., Hercules, CA, US) and equilibrated with 5–10 mM imidazole in PBS. The clarified lysate was then applied to Ni-Sepharose in the column to bind the tagged Fast-PETase. The Ni-Sepharose was then washed with PBS containing 20 mM imidazole, and the tagged Fast-PETase was eluted with PBS containing 300 mM imidazole. IMAC-purified Fast-PETase was applied to BioGel P-4 or P-6 resin (Bio-Rad, Inc.) in a spin column and centrifuged at 1000 × g to exchange the buffer with PBS (without imidazole). The concentration of Fast-PETase was estimated from the absorbance at 280 nm using an extinction coefficient of 1.4 (mg/ml)–1∙cm–1.

Enzymatic treatment of PET

The Fast-PETase purified as described in Section “Purification of PETase” was reconstituted at a concentration of 500 nM in 100 mM HEPES-NaOH buffer (pH 8.0), and the amorphous film prepared as described in Section “Preparation of PET substrate” was immersed in this reaction buffer in a 1.5 mL polypropylene microtube. The reaction was conducted at 50 °C by placing the reaction microtubes in an air-phase incubator without exchanging the reaction buffer with fresh enzyme, and the PET film was removed from the reaction buffer at the desired time. The film was washed briefly with water, dried in air for at least 15 min, weighed using an electronic balance, and photographed using a digital camera. The photographic images were analyzed by Fiji [23] to estimate the area loss and during the reaction.

After the weight measurement, the measured film sample was returned to the reaction buffer and incubated for the next weight measurement after further degradation. For the other analyses, separate film samples were prepared by dissecting an identical melt-quench film and used in the degradation experiment for different reaction times with Fast-PETase; the differences between the film samples should be minimal.

After the reaction, the pH of the reaction solution was measured with a portable LAQUA F-72 pH meter (HORIBA, Ltd., Kyoto, Japan).

Structural analysis of degraded PET

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The sample treated with Fast-PETase was fixed on a copper stub using electron-conductive glue (DOTITE, Fujikura Kasei Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan); the sample was coated with platinum using a JEC-3000FC coater (JEOL Inc., Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) that was operated at 20 mA for 90 s with the rotating sample stage at a tilt angle of 45° for 45 s and then at 0° for another 45 s.

The platinum-coated samples were observed using a JSM-7800F prime (JEOL Inc.) instrument operated at an accelerating voltage of 5.0 keV and a working distance of 6 mm. Some images were captured from the side direction by fixing the sample film perpendicularly on a copper stub with a working distance of 10 mm.

X-ray computed tomography (CT)

Micro-X-ray computed tomography (CT) was performed at BL8S2 of the Aichi Synchrotron Radiation Center (Aichi SRC, Seto, Aichi, Japan). Briefly, the sample was set on a rotational stage and illuminated with white X-rays (6–24 keV). The transmitted images were recorded with sample rotation from 0 to 360° at an interval of 0.1° using an ORCA-Flash4.0 sCMOS image sensor (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan) with a zoom lens: the pixel size corresponds to 0.65 μm2. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the obtained image dataset was performed at the beamline using TomoPy, which is a Python package for X-ray CT image analysis and image reconstruction [24]. Three-dimensional volumetric data were visualized using Fiji [23] and Molcer (WhiteRabit Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) for visual inspection. Slice images were analyzed using Fiji [23] to measure the thickness and its fluctuation to estimate the roughness of the film surface.

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD)

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) analyses were performed at the synchrotron facility, BL40B2, of SPring-8 (Hyogo, Japan). The wavelength of the X-rays used in this study was 1 Å, and the scattering/diffraction patterns were recorded with a Pilatus3 S 2 M instrument (Dectris Inc., Switzerland). The exposure times were 10 s and 5 s for SAXS and WAXD, respectively.

The scattering/diffraction patterns were circularly averaged using a beamline program and corrected for absorbance. Given the scattering vector q = (4π sin θ)/λ, where θ and λ are half of the scattering angle and the wavelength of the X-rays, respectively, the q-range of the SAXS and WAXD experiments covered 0.007‒0.4 Å–1 and 0.05‒2.5 Å–1, respectively. For some data, the WAXD profiles were manually rescaled and merged with the SAXS profiles using Microsoft Excel.

Results and discussion

Weight loss and visual inspection of the amorphous PET film after Fast-PETase treatment

First, the weight loss of the amorphous PET film treated with purified Fast-PETase was evaluated (Fig. 1), confirming the significant PET-degrading activity of the Fast-PETase used in this study. Visual inspection also detected a change from the clear appearance of the PET film before degradation to white after degradation by Fast-PETase, where the whiteness became more pronounced after degradation (Fig. 1), which is consistent with prior reports [12].

Notably, the degradation rate was slower during the initial phase (up to 12 h), then accelerated in the middle phase, and finally slowed again. As discussed later, slow degradation at the initial phase was probably due to the domain structure with slightly higher molecular order on the surface and less surface area on the smooth surface, as seen by WAXD, SEM, and SAXS (see Figs. 2, 5, and 6, respectively). The fast degradation in the middle phase was likely caused by pore formation increasing the surface area, as observed by SEM and SAXS. On the other hand, the slower degradation during the late period could be due to the significant reduction in the surface area of the film shape and a decrease in pH owing to the release of terephthalic acid to the solution: the end of the reaction was at pH 7.1, at which the degradation speed was shown to be slower than that at pH 8.0 in a previous study [14].

WAXD profiles of PET films degraded for different times: 0 h, 15.5 h, 26.5 h, 55.2 h, and 64.5 h. A Absorbance-corrected profiles with the weight loss percentage indicated for each of the profiles. B The WAXD profiles were normalized to the most intense peak at ca. 1.5 Å–1. Dashed line corresponds to the film before degradation, whereas the solid lines indicate PET degraded for 15.5 h, 26.5 h, 55.2 h, and 64.5 h; all profiles were similar. The arrow indicates the q-region where the diffraction intensity increased after degradation

Two mechanisms were hypothesized for this phenomenon: (i) an increase in the crystallinity upon degradation and (ii) the formation of a structure with voids having dimensions on the order of the wavelength of visible light ( ~ 10–7 m) in the PET film sample. Given the lower glass transition temperature for the surface of a polymer film [25], crystallization might be possible under the glass transition temperature of PET (ca. 50 °C) and was tested as a reason for whitening in this study. The residual PET films were analyzed using WAXD, X-ray CT, SEM, and SAXS to test these hypotheses. Furthermore, the structural changes in the PET film due to enzymatic degradation were tracked over the reaction time.

WAXD analysis

First, the fine structure of the film was assessed using WAXD to test the hypothesis that the increased turbidity of the film induced by Fast-PETase was due to the increased crystallinity of PET. The WAXD profile of PET before degradation (Fig. 2A) shows no sharp peaks but a broad peak composed of a number of diffraction peaks, indicating that the melt-quench film is amorphous. The intensity of the broad diffraction peak decreased with the increase in degradation time (Fig. 2A), indicating that PET molecules were gradually removed from the film by Fast-PETase. However, the sharpness of the WAXD profile did not change significantly, indicating that the film remained highly amorphous after degradation. Thus, the turbidity of the PET film observed after degradation by Fast-PETase was not caused by increased crystallinity of PET.

For detailed analysis of the change in the diffraction profile, all WAXD profiles were normalized relative to the most intense peak (Fig. 2B). Notably, the degradation profiles at 15.5, 26.5, 55.2, and 64.5 h were completely superimposable, whereas a slight difference in the diffraction profile was observed in a limited q region at approximately 1.75 Å-1 and 1.05 Å-1 between 0 h and 15.5 h (indicated by the arrow in Fig. 2B). This small difference is likely due to broadening of the diffraction, suggesting a relative enhancement in the disorder of the PET molecules at the beginning of degradation. Given that this change was very small and occurred only at an earlier stage, the enhanced disorder due to PETase-induced degradation may have resulted from the removal of the outer surface layer of the PET film, indicating that the initially removed part contained relatively well-ordered molecules. Notably, such a change specific to the earlier stage of degradation was also observed in the SEM and SAXS analyses, as shown in Sections “ SEM analysis” and “ SAXS analysis”, respectively.

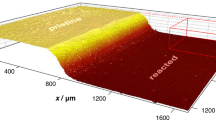

Micro X-ray CT analysis

Considering the WAXD results, the structural changes were analyzed on a larger scale. X-ray CT demonstrated that the surface morphology of the PET film was flat and smooth before degradation (Fig. 3). During degradation, the film gradually became thinner and exhibited a rougher surface, as indicated by the larger fluctuations in the film thicknesses in a cross-section for longer degradation: the average ± standard deviation and the ratio of the standard deviation to the average in a cross-sectional slice image of the tomogram at 10 different positions were 154.8 ± 1.1 μm (0.72%), 112.8 ± 7.8 μm (7.0%), 78.3 ± 6.8 μm (8.7%), and 39.8 ± 5.9 μm (15.0%) for 0 h, 26.5 h, 55.2 h, and 64.5 h, respectively. In most parts of the film, no significant void spaces were observed inside the film (Fig. 3). These observations indicate that the erosion of the PET film by Fast-PETase primarily occurred at the surface, where the short PET molecules depolymerized by Fast-PETase were detached into the supernatant, as revealed by HPLC analysis, which revealed three major product molecules in the supernatant: terephthalic acid, mono(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalic acid, and bis(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalic acid.

Interestingly, one side of the film surface became rougher than the other as the reaction progressed (Fig. 4A–D). Although this indicates a difference in the rate of structural decay of the two surfaces of the film, the reason for the difference is not clear. However, this phenomenon can be attributed to the method used to prepare the amorphous PET film. In other words, PET film preparation could be one of the keys to controlling enzymatic digestibility, which is important for developing highly degradable PET materials.

SEM images of PET film before (A and B) and after degradation for 26.5 h (C and D). The scale bars indicate 10 μm, except for (B), where it represents 1 μm. A and B: PET before degradation at magnifications of ×1000 (A) and ×10,000 (B). Largely degraded part of the PET film observed at a magnification of ×1000 in the top view (C) and side view from the edge (D)

SEM analysis

Top-view SEM clearly revealed that the initially very flat and smooth surface of the PET film at the submicron scale before degradation (Fig. 4A, B) became undulated after degradation by Fast-PETase (Fig. 4C, D), as previously reported [12, 14]. Observations of the surface from the side confirmed the presence of depressions that were not convex (Fig. 4D).

This indicates that the surface area before degradation is small at the beginning and becomes larger as the reaction progresses. Given that structural erosion of the PET film occurs from the surface, the slow degradation at the initial phase (see Fig. 1) is due to the flat and smooth surface, which minimizes the surface area and accelerates when the surface becomes rougher during degradation.

The films were further observed at different degradation times to track the structural changes in the amorphous PET film induced by Fast-PETase (Fig. 5). Before degradation, the surface was flat and smooth, whereas after 4 h of degradation, many depressions with a diameter of 1 μm were apparent. Given that areas with undegraded surface were found close to these depressions, the depressions were structures generated by fast-PETase in the initial phase. The surface of this depression was not as rough as that of the PET degraded for 12 h, as shown below.

SEM observation of morphological changes of film surface during treatment with Fast-PETase at three magnifications: ×1000, ×5000, and ×20,000. A–C: 4 h; D–F: 12 h; G–I: 26.5 h; J–L: 55.2 h; M–O: 64.5 h. Asterisks in (B and C) show a flat and undegraded surface, and the arrowheads in (E and F) show pores with diameters of 10‒100 nm

After 12 h of degradation, no depressions formed at 4 h, and the surface appeared flat at a lower magnification (Fig. 5D). However, hollows with a diameter of 2‒4 μm appeared, and the surface appeared sandy at a higher magnification due to the granularity of many smaller pores with a diameter of 10‒100 nm (indicated by the arrowheads in Fig. 5E, F). This hollow structure was also found less frequently after 4 h of degradation and is thus considered a characteristic feature that appears after the initial depressions (Fig. 5A–C) disappear.

After 26.5 h, the surface became highly rough even at a lower magnification due to the larger diameter (10 μm or more) of the holes (Fig. 5G). Closer observation revealed many pores with diameters of 100 nm or less on the surface of the depressions (Fig. 5H, I), which were found specifically in the hollows of the sample degraded for 12 h (Fig. 5E, F). Thus, the hollows with sizes of a few micrometers frequently observed after 12 h of degradation might have enlarged or fused to form larger holes.

After 55.2 h, the crater-like depressions, which were also found in some areas after 26.5 h, were sufficiently enlarged to expose a relatively flat and smooth surface when viewed at lower magnification (Fig. 5J). However, the higher-magnification images clearly show more porous surfaces with smaller pore sizes (10–100 nm) and larger numbers of pores than at 26.5 h (Fig. 5K, L). These porous features were maintained at 64.5 h, whereas the porosity of the 1 μm pores decreased; consequently, the surface became flatter with pores 100 nm or less in diameter (Fig. 5N, O). In a wider view (Fig. 5M), crater-like depressions with a diameter of ~50 μm appeared more clearly. In summary, degradation by Fast-PETase induced hierarchical boring on the order of 10–5 m to 10–8 in the PET film.

It was thus concluded that the turbidity of the PET film after Fast-PETase degradation was due to the porous structure generated by Fast-PETase and not to crystallization of the amorphous parts, as discussed in Section “Weight loss and visual inspection of the amorphous PET film after Fast-PETase treatment”. Further studies will be required to determine the factors responsible for this degradation pattern: variability in PETase activity, heterogeneous structure of the PET film, or any other factors.

SAXS analysis

Although scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is a powerful tool for visualizing the fine structure of degraded PET, only a local view of the structure is provided. Therefore, considering whether the SEM observations truly reflect the structure as a whole is necessary. SAXS was used to visualize the mesoscale structure of the degraded PET film in an averaged view. Two notable observations were made.

First, the scattering intensity around q = 0.022 Å–1, observed before degradation, decreased quickly (in the first 12 h) after treatment with Fast-PETase (Fig. 6A), indicating that the structure represented by this scattering feature was selectively attacked and removed by Fast-PETase. Furthermore, this signal shifted to lower q, accompanied by a decrease in intensity during the early stages of degradation, as shown in the Lorentz-factor-corrected plot (Fig. 6A, inset). Given the equation d = 2π/q, where d indicates the spatial periodicity, the size of the structural component represented by this scattering changed from ca. 290 to 320 Å. Although careful discussion is required for describing the structure represented by this scattering signal, it may represent a randomly distributed denser region in a less dense region, which has been proposed as a “nodule” in some previous studies [26, 27].

SAXS profiles of PET film treated with Fast-PETase for different reaction times. The degradation experiment was independently conducted to obtain data for (A) (earlier stage of degradation) and (B) (later stage). A Lorentz-factor-corrected plot (q – q2 ∙ I plot) is also shown in the inset of Panel (A); arrows indicate the peak maxima for the films degraded for 0 h and 4 h. The scattering profiles in B were prepared by merging the WAXD data with SAXS data as described in Section “Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD)”. The data acquired after 68.8 h of degradation were fitted (closed circles in Panel B) and followed a power law with an exponent of −3.2 along the scattering vector q, as shown by the black line

The second specific structural change induced by Fast-PETase was observed as an increase in the scattering at the q-region below 0.02 Å-1 in the SAXS profile, up to a reaction time of 12 h. The synchronicity in the appearance of small pores in the SEM images (diameter of 10‒100 nm) may represent observations after degradation for 12 h and beyond (Fig. 5), where the contrast between the PET substrate and air becomes more pronounced due to the boring. Scattering in this low q region increased continuously after 12 h of degradation, and finally, the scattering profile at 68.8 h followed a power law with an exponent of −3.2 in the observed q range (Fig. 6B, black line). Given that such a linear scattering profile in a double-logarithmic plot over a wide intensity range was demonstrated for lignite coal and discussed for the surface fractal of the pores in it [28], the surface fractal dimension of 2.8 ( = 6–3.2) is deduced for the PET film significantly degraded by Fast-PETase, suggesting that the pores with diameters of 10–7‒10–8 m tend to form a three-dimensionally rough surface rather than a smooth surface. This is also consistent with the SEM observations, which showed that nested porous structures with dimensions of 10–7 m or smaller became dominant after 12 h of degradation.

Notably, this study revealed several structural changes that occurred specifically in the earlier degradation stage as follows: (i) broadening of the amorphous halo in WAXD profiles (Fig. 2B), (ii) removal of the smooth surface, as visualized by SEM (Figs. 4, 5), and (iii) a decrease in the SAXS signal at approximately q = 0.022 Å–1 (Fig. 6A). Summarizing these observations, the surface layer of the amorphous PET film might contain randomly distributed denser domains (nodules) in less dense regions. Removing this denser domain structure may be attributed to the broadening of the amorphous halo in the WAXD profile. Specifically, this denser domain on the surface is responsible for the slow degradation rate in the initial phase shown in Fig. 1, and the surface layer with these denser domains did not allow PETase to bore smaller holes ( ~ 100 nm) and yielded fewer porous features in the initial phase, as observed in the SEM images. Thus, the results of this study support the idea that the surface and core structures differ for amorphous PET films. Feasibly, PETase can be used as a probe to assess the polymer structure of PET in future studies.

Comparison with the enzymatic degradation of other polymers

The results of this study were compared with the structural changes in other polymers. Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) is a typical biodegradable polymer and has been extensively analyzed for its ability to undergo enzymatic degradation. PLA is known to be degraded by several types of enzymes, such as protease K, cutinase, and lipase [29]. Some studies have investigated the relationship between degradability and polymer structure. For example, it was reported that proteinase K degraded amorphous PLA more easily [30]. Another study also revealed that proteinase K and a cutinase-like enzyme degraded the amorphous part more preferentially than the crystalline part in PDLA (poly(d-lactic acid) film) [31]. Such preferential degradation concerning crystallinity is important information in PET degradation by PETase, which will be tested in future studies for crystalline PET solids.

The particle size of the PLA also influenced the degree of enzymatic degradation as reported in a previous study. Milled powders of PLA and PCL (poly(ε-caprolactone)), the particle size for which was categorized by sieves, were subjected to treatment with lipase and proteinase K, and the smaller particle size of the polymer resulted in better degradability [32]. These results indicate that the surface is the reaction site for the enzymatic degradation of PLA and PCL as well as PET, as discussed in this study. Notably, this idea—the importance of the substrate surface for its degradation—is shared knowledge in the field of cellulose biodegradation research, as discussed in previous studies [33, 34].

Finally, our data were compared with those of cellulose biodegradation because cellulose has been present on Earth for more than a few hundred million years; thus, cellulase is a good example of an efficient biodegradation system for solid polymers that has evolved for a much longer time than any plastic-degrading enzymes on Earth. In our previous study [35], the degradation of bacterial cellulose by crude cellulase was analyzed using SAXS, where an overall decrease in the scattering intensity was observed without changes in the scattering features, indicating that the amount of the cellulose simply decreased without significant structural changes at the scale represented by q = 0.04‒0.2 Å–1. SEM observations in the same study also demonstrated that the cellulose microfibrils remained generally intact despite the appearance of large cavities between the fiber bundles in a bacterial cellulose film [35]. Another study analyzed the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peaks in WAXD profiles and revealed that the lateral crystallite size of cellulose decreased because of cellulase degradation [36]. These previous observations of cellulose degradation contrast with the structural decay of the PET film by Fast-PETase observed in this study (Figs. 2, 5, 6). This is plausibly due to the structural differences in PET and cellulose due to differences in the assembly of the polymer molecules, as explained below.

Native cellulosic material is generally a woven textile of crystalline cellulose microfibrils with a lateral size of 10-9‒10-8 m, whereas the PET film is a continuous mass in which many chains are entangled without a well-defined elementary structural unit, such as the microfibrils in cellulose. Each cellulose microfibril is assumed to be degraded independently by cellulase, and the structural features appear to be maintained on average. However, structural degradation of the PET film by Fast-PETase may preferentially occur close to the surface, as revealed by the specific decrease in the SAXS signal at approximately q = 0.022 Å–1 at the beginning of degradation, which is not observed for cellulose. Therefore, the polymer structure governs enzymatic degradability. In other words, the design of the polymer structure is as important as enzyme engineering for realizing eco-friendly PET or plastic materials in general.

The relationship between the polymer structure and enzymatic degradation of cellulose has aided in understanding the structure of cellulose and the function of cellulase. For example, the unidirectional degradation of native cellulose microfibrils by cellobiohydrolase was used to demonstrate parallel chain packing in native cellulose microfibrils [37]. In contrast, parallel-chain packing in native cellulose allowed the processive action of cellobiohydrolases to be clearly understood [38,39,40]. Such interrelated research is also required for PET and PETase to deepen our understanding of the mechanism of decay of the PET structure by PETase. Thus, studying PETase from the perspective of PET structure is highly valuable for studying not only PETase but also PET, where many issues remain obscure despite the long history of research [19,20,21]. In this context, crystalline PET degradation by PETase should be analyzed in the near future, as was the case for the amorphous PET film in this study. The PET container for foods/drinks has a crystalline region, which is important for the social deployment of the biochemical recycling of PET.

Given that cellulase is a good example of the efficient degradation of polymer solids, designing a PETase protein by referring to cellulase is worthwhile. The fusion of the carbohydrate-binding module (CBM) to PETase, which is also found in nature [41], has been shown to enhance the PET-degrading activity [42,43,44,45]. In addition to implementing the absorption function of CBM, the synergistic effect of mixing enzymes with different modes of action, such as exo-type cellulases (cellobiohydrolases) and endoglucanases, is a promising strategy [46]. To this end, the mode of action of many PETase proteins must be clarified to design a high-performance PETase cocktail. A cellulasewise strategy is a promising way to develop higher-performance PETases. This approach is set apart from state-of-the-art technologies, such as protein engineering with bioinformatics. Polymer structure analysis during enzymatic degradation is important for the sustainable utilization of plastic materials and for the research and development of biodegradable plastics.

Conclusion

Multiscale structural analysis in this study revealed that Fast-PETase gradually eroded the PET film from the surface and bored many pores with diameters of 10-5 to 10-8 m. The domain structure with dimensions of 10-8 m on the surface of the film was preferentially removed at earlier reaction times. However, the crystallinity of PET did not change after degradation. In summary, Fast-PETase erodes the amorphous PET film from the surface. This study provides a perspective on the degradation of solid PET by PETase. This information is valuable for comparing the enzymatic efficacy of PETase variants for PET degradation and will help pave the way for a circular economy of PET materials in the future by conferring full biodegradability to PET, a conventional plastic.

Data availability

The derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, DT, upon request.

References

Hidalgo-Ruz V, Gutow L, Thompson RC, Thiel M. Microplastics in the marine environment: a review of the methods used for identification and quantification. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:3060–75.

Li Y, Chen L, Zhou N, Chen Y, Ling Z, Xiang P. Microplastics in the human body: a comprehensive review of exposure, distribution, migration mechanisms, and toxicity. Sci Total Environ. 2024;946:174215.

Ragaert K, Delva L, Van Geem K. Mechanical and chemical recycling of solid plastic waste. Waste Manag. 2017;69:24–58.

Jehanno C, Alty JW, Roosen M, De Meester S, Dove AP, Chen EYX, et al. Critical advances and future opportunities in upcycling commodity polymers. Nature. 2022;603:803–14.

Kabir AHME, Sekine M, Imai T, Yamamoto K. Microplastics pollution in the seto inland sea and sea of japan surrounded yamaguchi prefecture areas, japan: Abundance, characterization and distribution, and potential occurrences. J Water Environ Technol. 2020;18:175–94.

Tsuchiya M, Kitahashi T, Nakajima R, Oguri K, Kawamura K, Nakamura A, et al. Distribution of microplastics in bathyal- to hadal-depth sediments and transport process along the deep-sea canyon and the kuroshio extension in the northwest pacific. Mar Pollut Bull. 2024;199:115466.

Nihei Y, Ota H, Tanaka M, Kataoka T, Kashiwada J. Comparison of concentration, shape, and polymer composition between microplastics and mesoplastics in japanese river waters. Water Res. 2024;249:120979.

Isobe A, Uchida K, Tokai T, Iwasaki S. East asian seas: a hot spot of pelagic microplastics. Mar Pollut Bull. 2015;101:618–23.

Peng L, Fu D, Qi H, Lan CQ, Yu H, Ge C. Micro- and nano-plastics in marine environment: Source, distribution and threats — a review. Sci Total Environ. 2020;698:134254.

Ghasemi MH, Neekzad N, Ajdari FB, Kowsari E, Ramakrishna S. Mechanistic aspects of poly(ethylene terephthalate) recycling–toward enabling high quality sustainability decisions in waste management. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28:43074–101.

Müller R-J, Schrader H, Profe J, Dresler K, Deckwer W-D. Enzymatic degradation of poly(ethylene terephthalate): Rapid hydrolyse using a hydrolase from t. Fusca. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2005;26:1400–5.

Yoshida S, Hiraga K, Takehana T, Taniguchi I, Yamaji H, Maeda Y, et al. A bacterium that degrades and assimilates poly(ethylene terephthalate). Science. 2016;351:1196–9.

Sulaiman S, Yamato S, Kanaya E, Kim J-J, Koga Y, Takano K, et al. Isolation of a novel cutinase homolog with polyethylene terephthalate-degrading activity from leaf-branch compost by using a metagenomic approach. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:1556–62.

Lu H, Diaz DJ, Czarnecki NJ, Zhu C, Kim W, Shroff R, et al. Machine learning-aided engineering of hydrolases for pet depolymerization. Nature. 2022;604:662–7.

Lee SH, Seo H, Hong H, Park J, Ki D, Kim M, et al. Three-directional engineering of ispetase with enhanced protein yield, activity, and durability. J Hazard Mater. 2023;459:132297.

Joo S, Cho IJ, Seo H, Son HF, Sagong H-Y, Shin TJ, et al. Structural insight into molecular mechanism of poly(ethylene terephthalate) degradation. Nat Commun. 2018;9:382.

Weigert S, Perez-Garcia P, Gisdon FJ, Gagsteiger A, Schweinshaut K, Ullmann GM, et al. Investigation of the halophilic pet hydrolase pet6 from vibrio gazogenes. Protein Sci. 2022;31:e4500.

Burgin T, Pollard BC, Knott BC, Mayes HB, Crowley MF, McGeehan JE, et al. The reaction mechanism of the ideonella sakaiensis petase enzyme. Commun Chem. 2024;7:65.

Geil PH. Morphology of amorphous polymers. Prod RD. 1975;14:59–71.

Renninger AL, Uhlmann DR. On the structure of glassy polymers. Iii. Small-angle x-ray scattering from amorphous polyethylene terephthalate. J Polym Sci: Polym Phys Ed. 1976;14:415–25.

Calvert P. Order in amorphous polymers. Nature. 1978;271:507–8.

Teufel F, Armenteros JJA, Johansen AR, Gíslason MH, Pihl SI, Tsirigos KD, et al. Signalp 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40:1023.

Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–82.

Gürsoy D, De Carlo F, Xiao X, Jacobsen C. Tomopy: A framework for the analysis of synchrotron tomographic data. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2014;21:1188–93.

Tanaka K, Takahara A, Kajiyama T. Rheological analysis of surface relaxation process of monodisperse polystyrene films. Macromolecules. 2000;33:7588–93.

Yeh GSY. Morphology of amorphous polymers and effects of thermal and mechanical treatments on the morphology. Pure Appl Chem. 1972;31:65–90.

Konishi T, Okamoto D, Tadokoro D, Kawahara Y, Fukao K, Miyamoto Y. Origin of saxs intensity in the low-q region during the early stage of polymer crystallization from both the melt and glassy state. Phys Rev Mater. 2018;2:105602.

Schmidt PW. Small-angle scattering studies of disordered, porous and fractal systems. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:414–35.

Shalem A, Yehezkeli O, Fishman A. Enzymatic degradation of polylactic acid (pla). Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2024;108:413.

Cai H, Dave V, Gross RA, McCarthy SP. Effects of physical aging, crystallinity, and orientation on the enzymatic degradation of poly(lactic acid). J Polym Sci Part B: Polym Phys. 1996;34:2701–8.

Kawai F, Nakadai K, Nishioka E, Nakajima H, Ohara H, Masaki K, et al. Different enantioselectivity of two types of poly(lactic acid) depolymerases toward poly(l-lactic acid) and poly(d-lactic acid). Polym Degrad Stab. 2011;96:1342–8.

Hino S, Kawasaki N, Yamano N, Nakamura T, Nakayama A. Effects of particle size on marine biodegradation of poly(l-lactic acid) and poly(ε-caprolactone). Mater Chem Phys. 2023;303:127813.

Igarashi K, Wada M, Hori R, Samejima M. Surface density of cellobiohydrolase on crystalline celluloses: A critical parameter to evaluate enzymatic kinetics at a solid-liquid interface. FEBS J. 2006;273:2869–78.

Igarashi K, Uchihashi T, Koivula A, Wada M, Kimura S, Okamoto T, et al. Traffic jams reduce hydrolytic efficiency of cellulase on cellulose surface. Science. 2011;333:1279–82.

Penttilä PA, Imai T, Hemming J, Willför S, Sugiyama J. Enzymatic hydrolysis of biomimetic bacterial cellulose-hemicellulose composites. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;190:95–102.

Imai T, Naruse M, Horikawa Y, Yaoi K, Miyazaki K, Sugiyama J. Disturbance of the hydrogen bonding in cellulose by bacterial expansin. Cellulose. 2023;30:8423–38.

Chanzy H, Henrissat B. Undirectional degradation of valonia cellulose microcrystals subjected to cellulase action. FEBS Lett. 1985;184:285–8.

Imai T, Boisset C, Samejima M, Igarashi K, Sugiyama J. Unidirectional processive action of cellobiohydrolase cel7a on valonia cellulose microcrystals. FEBS Lett. 1998;432:113–6.

Kim N-H, Imai T, Wada M, Sugiyama J. Molecular directionality in cellulose polymorphs. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:274–80.

Igarashi K, Koivula A, Wada M, Kimura S, Penttila M, Samejima M. High speed atomic force microscopy visualizes processive movement of trichoderma reesei cellobiohydrolase i on crystalline cellulose. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:36186–90.

Erickson E, Gado JE, Avilán L, Bratti F, Brizendine RK, Cox PA, et al. Sourcing thermotolerant poly(ethylene terephthalate) hydrolase scaffolds from natural diversity. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7850.

Zhang Y, Wang L, Chen J, Wu J. Enhanced activity toward pet by site-directed mutagenesis of thermobifida fusca cutinase–cbm fusion protein. Carbohydr Polym. 2013;97:124–9.

Weber J, Petrovic D, Strodel B, Smits SHJ, Kolkenbrock S, Leggewie C, et al. Interaction of carbohydrate-binding modules with poly(ethylene terephthalate). Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;103:4801–12.

Dai L, Qu Y, Huang J-W, Hu Y, Hu H, Li S, et al. Enhancing pet hydrolytic enzyme activity by fusion of the cellulose–binding domain of cellobiohydrolase i from trichoderma reesei. J Biotechnol. 2021;334:47–50.

Graham R, Erickson E, Brizendine RK, Salvachúa D, Michener WE, Li Y, et al. The role of binding modules in enzymatic poly(ethylene terephthalate) hydrolysis at high-solids loadings. Chem Catal. 2022;2:2644–57.

Teeri TT. Crystalline cellulose degradation: new insight into the function of cellobiohydrolases. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15:160–7.

Acknowledgements

SEM observations were performed at a collaborative facility at the Research Institute for Sustainable Humanosphere (RISH) at Kyoto University, Cellulosic Advanced Nanomaterials Development Organization (CAN-DO). A micro-X-ray CT experiment was performed at BL8S2 at Aichi SRC (202403106). SAXS measurements were performed at BL40B2 (2023B1470, 2024A1381, 2024B1389, and 2025A1053) and BL19B2 (2024A1728) at SPring-8 and BL8S3 at Aichi SRC (202306168). WAXD measurements were performed at BL40B2 at SPring-8 (2023B1470, 2024A1381, and 2024B1389). We thank the beamline staff at the synchrotron facilities for their support of the experiments. A portion of this study was financially supported by the Humanosphere Science Research Program in 2024 and 2025 and the Mision-2 Research Program in 2023 and 2024 from RISH, Kyoto University. We acknowledge Dr. Susumu Fujiwara at the Kyoto Institute of Technology, Dr. Shosuke Yoshida at the Nara Institute of Science and Technology, and Dr. Takashi Konishi at Kyoto University for discussing the experimental results.

Funding

This work was partially supported by RISH at Kyoto University with Humanosphere Science Research; Mission-2 Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DT, conceptualization; DT and TI, methodology; DT and TI, formal analysis; DT and TI, investigation; DT and TI, resources; DT and TI, data curation; DT and TI, writing–original draft; TI, writing–review and editing; DT and TI, visualization; TI, supervision; TI, project administration; DT and TI, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tadokoro, D., Imai, T. Structural decay of poly(ethylene terephthalate) by enzymatic degradation. Polym J 58, 167–177 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-025-01111-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-025-01111-y