Abstract

Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD), first described 25 years ago, confers an extremely high and lifelong cancer risk, including haematologic, brain, and gastrointestinal tract malignancies, and is associated with several non-neoplastic features. Our understanding of this condition has improved and novel assays to assist CMMRD diagnosis have been developed. Surveillance protocols need adjustment taking into account recent observational prospective studies assessing their effectiveness. Response to immune checkpoint inhibitors and the effectiveness and toxicity of other treatments have been described. An update and merging of the different guidelines on diagnosis and clinical management of CMMRD into one comprehensive guideline was needed. Seventy-two expert members of the European Reference Network GENTURIS and/or the European care for CMMRD consortium and one patient representative developed recommendations for CMMRD diagnosis, genetic counselling, surveillance, quality of life, and clinical management based on a systematic literature search and comprehensive literature review and a modified Delphi process. Recommendations for the diagnosis of CMMRD provide testing criteria, propose strategies for CMMRD testing, and define CMMRD diagnostic criteria. Recommendations for surveillance cover each CMMRD-associated tumour type and contain information on starting age, frequency, and surveillance modality. Recommendations for clinical management cover cancer treatment, management of benign tumours or non-neoplastic features, and chemoprevention. Recommendations also address genetic counselling and quality of life. Based on existing guidelines and currently available data, we present 82 recommendations to improve and standardise the care of CMMRD patients in Europe. These recommendations are not meant to be prescriptive and may be adjusted based on individual decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A major role of the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system is to correct replication errors that escape proofreading by the replicative DNA polymerases Pol ε and Pol δ. MMR deficiency, resulting from inactivation of one of four MMR genes (MLH1, MIM# 120436; MSH2, MIM# 609309; MSH6, MIM# 600678; PMS2, MIM# 600259), leads to an increased mutation rate and is frequently found in several types of cancer [1]. Constitutional (hereafter referred to as germline) pathogenic variants (PV) in one of these four genes are associated with an increased cancer risk involving multiple organs. Heterozygous germline MMR gene PV cause Lynch syndrome (LS), an autosomal dominant, adult-onset cancer syndrome mainly predisposing to colorectal and endometrial carcinoma, as well as other cancers at a lower frequency [2]. In LS cancers, MMR deficiency results from somatic inactivation of the second allele. Constitutional MMR deficiency (CMMRD) is caused by biallelic germline PV in one of the MMR genes. Individuals with CMMRD, therefore, lack a functional DNA MMR system in all tissues, which is critical for the maintenance of genomic stability by repair of DNA replication errors. An increased constitutional mutation rate is proposed to drive tumourigenesis in several organ systems. Since the first two reports of CMMRD in 1999 [3, 4], well over 200 children and young adults with this recessively inherited condition have been reported, showing it to be a distinct early-onset cancer predisposition syndrome (OMIM #276300).

Although attenuated forms of CMMRD exist [5,6,7], the cancer risk in CMMRD is likely the highest among cancer predisposition syndromes, with cancer development occurring as early as the first year of life [8]. According to our review of published patients, as well as data from the C4CMMRD database and a recently published patient cohort [9] (patients may partly overlap), 80–90% of CMMRD patients develop their first tumour before the age of 18 years and about half of the patients before the age of 10 years. The known spectrum of CMMRD-associated cancers is broad and, in essence, any cancer type could be caused by CMMRD. The three most frequent cancer groups are (i) haematological malignancies diagnosed in ~40% of patients, with T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma being most prevalent, (ii) malignant brain tumours in ~55% of patients, most frequently high-grade gliomas, and, (iii) colorectal carcinomas and other LS-associated tumours in ~50% of patients [10]. Most patients develop digestive tract adenoma often with high-grade dysplasia or (oligo-)polyposis in the second decade of life. Tumour types less frequently seen in CMMRD include sarcoma, neuroblastoma, and nephroblastoma [11,12,13,14,15].

CMMRD is also associated with distinctive non-neoplastic manifestations. The most prevalent non-neoplastic features are café-au-lait maculae reminiscent of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), other hypo- and hyper-pigmented skin patches, and multiple brain developmental venous anomalies [16, 17]. The MMR system is also involved in immunoglobulin class-switch recombination and in somatic hypermutation, two processes needed for B cell maturation and for diversification and specification of the immunoglobulin repertoire. Its deficiency may result in IgG2/4 subclass deficiency, IgA deficiency, or - rarely - more severe phenotypes [18].

The estimated birth incidence of CMMRD, supported by empirical data [19], is approximately one in a million if parents are not related [20]. The prevalence might be substantially higher in populations with founder mutations and/or a high rate of parental consanguinity, with approximately half of CMMRD cases being homozygous for an MMR PV [13]. Over 60% of CMMRD cases have biallelic PMS2 PV, over 20% biallelic MSH6 PV, and less than 20% biallelic PV in either MLH1 or MSH2 [9, 15]. These numbers reflect the estimated population prevalence of heterozygous PV in these four MMR genes, in which PMS2 and MSH6 are about 2.5–4 times more prevalent than PV in MLH1 and MSH2 [21]. The substantially lower penetrance of monoallelic MSH6 and especially PMS2 PV than that of MSH2 and MLH1 PV means CMMRD patients often lack a family history of LS-associated cancers [2, 13].

A diagnosis of CMMRD requires germline genetic testing to identify the causative MMR PV. To provide clear criteria to select childhood or adolescent cancer patients for CMMRD testing, the European consortium Care for CMMRD (C4CMMRD) formulated a scoring system from the cancer type, additional non-malignant neoplasia, CMMRD-associated non-neoplastic features, and family history [15]. As a rare differential diagnosis, CMMRD testing may also be indicated in children without cancer who are suspected to have sporadic NF1 or Legius syndrome but in whom no germline NF1 or SPRED1 PV has been identified by comprehensive testing [19, 20]. Several ancillary tests have been developed that assess constitutional loss of MMR function, the pathomechanism underlying CMMRD, and are used to confirm CMMRD in cases where genetic testing renders an inconclusive result [22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

CMMRD patients need to be subjected to extensive surveillance due to the high cancer risk and broad tumour spectrum. Several surveillance protocols have been published [8, 11, 29]. In observational prospective studies, these protocols have proven to be effective for brain and digestive tract tumours, but not for haematological malignancies [12, 30].

CMMRD cancers are inherently MMR deficient and this shapes tumour molecular pathology. MMR deficient cancers have increased tumour mutation burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI). They are frequently classified as hypermutated, which is typically defined as a TMB ≥ 10 mutations per megabase. Mainly in CMMRD brain tumours, but also other tumours, it is common to find concurrent polymerase proofreading deficiency caused by missense PV in the exonuclease domains of replicative DNA polymerases Pol ε or Pol δ [31]. This results in ultramutated tumours with TMB ≥ 100 mutations per megabase, specific mutational signatures, and MSI that is not detectable by classical fragment length analysis-based MSI testing, but by the more sensitive methods that have been developed for MSI testing in constitutional DNA of CMMRD patients [23, 31,32,33]. Hypermutated and MMR deficient tumours are associated with translation of coding variants producing tumour-specific, immunogenic neoantigens that render the tumours responsive to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) [34]. It follows that ICI are a promising drug class in the treatment of cancer patients with CMMRD, with clinical responses being observed in gastrointestinal and brain tumours [35,36,37]. MMR deficiency also confers therapy-resistance to tumours, in particular against chemotherapies that rely on functional MMR for their mechanism of action. The inefficacy of temozolomide to treat patients with MMR deficient brain tumours is of particular note for CMMRD patients [38].

Scope of the guidelines

Existing guidelines for CMMRD diagnosis and cancer surveillance were established by two expert groups, the European consortium C4CMMRD and the International Replication Repair Deficiency Consortium (IRRDC) along with collaborating health care organizations [8, 11, 15, 20, 29, 39]. Recent developments regarding the diagnosis of CMMRD, in particular improved understanding of the CMMRD clinical phenotype and the development of reliable and relatively low cost ancillary assays to complement genetic testing, and regarding the efficacy of cancer surveillance protocols require up-to-date guidelines. Moreover, CMMRD healthcare practice varies and professional guidelines on genetic counselling, quality of life, and cancer treatment are so far lacking. Therefore, based on our current knowledge, ERN GENTURIS and C4CMMRD combined efforts to update the different guidelines on diagnosis and surveillance as well as to formulate recommendations for clinical treatment, quality of life, and genetic counselling of CMMRD patients in one comprehensive guideline. With these guidelines we aim at assisting clinical management of people with CMMRD in Europe and beyond. These guidelines do not represent nor intend to be a legal standard of care, they should support clinical decision making.

Methods

A CMMRD Guideline Group (GG) was established comprising clinicians specialised in clinical genetics, paediatric (neuro-)oncology and haematology, neuro-surgery, (paediatric) gastroenterology, radiology, pathology, and clinical psychology, with expert experience in the management of CMMRD, and (molecular) geneticists specialised in the diagnosis of CMMRD. The nineteen members of the GG were led by a Core Working Group (CWG) consisting of eight members including one patient representative.

Based on the defined scope of the guidelines, PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) questions were formulated by the CWG and approved by the GG. Based on these PICO questions, Agència de Qualitat i Avaluació Sanitàries de Catalunya (AQuAS) extracted 332 articles from three databases (PubMed, Cinhal and Embase) using the following terms: CMMRD [Title/Abstract] OR CMMR-D [Title/Abstract] OR “constitutional mismatch repair deficiency” [Title/Abstract] OR “constitutive mismatch repair deficiency” [Title/Abstract] OR “biallelic mismatch repair deficiency” [Title/Abstract] OR bMMRD [Title/Abstract] OR “mismatch repair cancer syndrome” [Title/Abstract] OR “OMIM 276300”. Another 20 articles were selected using citation searching. From these 352 articles, 258 were excluded as they were conference articles, were not written in English, were not responding to any of the questions of interest, were not referring to individuals with CMMRD, and/or contained data already included from other references. The remaining 94 articles were summarised by AQuAS in a comprehensive literature review.

The CWG members drafted recommendations for CMMRD diagnosis, genetic counselling, surveillance, quality of life, and clinical management building on this literature review with additional articles they identified and their expert knowledge. These recommendations were approved by the GG and then subjected to a modified Delphi process. Delphi is a structured communication technique in which opinions of a large number of experts are assessed on a topic in which there is no consensus. Experts included in this exercise were all members of the CWG and the GG as well as 53 external experts identified by the CWG and the GG together. The Delphi survey consisted of two rounds, in which the threshold for consensus was defined by a simple majority of the survey participants agreeing with the recommendation ( > 60% rated ‘agree’ or ‘totally agree’). Recommendations were graded using a 4-point Likert scale (totally disagree, disagree, agree, totally agree) and a justification for the given rating was obligatory. Even if the consensus threshold was met in the first Delphi round, recommendations were still modified if a stronger consensus was thought achievable from written responses. The facilitator of the Delphi survey provided anonymised summaries of the experts’ decisions after each round as well as the reasons they provided for their judgements.

As is typical for many rare diseases, the volume of peer-reviewed evidence available to consider for these guidelines was small and came from a limited number of articles, which typically reported on individual cases or small series. To balance the weight of both published evidence and quantify the wealth of expert experience and knowledge, we have used the following scale to grade the recommendations: (i) strong: Expert consensus AND consistent evidence; (ii) moderate: Expert consensus WITH inconsistent evidence AND/OR new evidence likely to support the recommendation, and (iii) weak: Expert majority decision WITHOUT sufficient evidence. Expert consensus (an opinion or position reached by a group as whole) or expert majority decision (an opinion or position reached by the majority of the group) is established after reviewing the results of the modified Delphi approach within the CWG.

Recommendations were written in one of four stylistic formats: Should, Should Probably, Should Probably Not, Should Not:

-

Should & Should Not, were taken to mean most well-informed people (those who have considered the evidence) would take this action.

-

Should Probably & Should Probably Not, were taken to mean the majority of informed people would take this action, but a substantial minority would not.

The full details of the guideline including literature search, reference list and Delphi process can be found on the ERN GENTURIS website: https://www.genturis.eu/l=eng/Guidelines-and-pathways/Clinical-practice-guidelines.html.

Results

Eighty-two recommendations were formulated (Table 1). After two Delphi rounds, an agreement of 68 to 100% (median 92) was reached for all recommendations and their strength was graded as weak (n = 5), moderate (n = 23) or strong (n = 54). The high rate of weak and moderate recommendations is mainly due to the paucity of data in the literature.

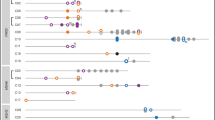

Fourteen recommendations for the diagnosis of CMMRD (Table 1a) provide indication criteria for CMMRD testing based on (revised) C4CMMRD indication criteria for CMMRD testing in paediatric/young adult cancer patients (Table 2) and in children suspected of having sporadic NF1/Legius syndrome without a cancer in whom genetic testing cannot confirm either of these suspected diagnoses (Table 3). These recommendations also include criteria based on the phenotype of the tumour in paediatric cancer patients (Table 1a). Further recommendations define CMMRD testing strategies, which may include ancillary tests (Table 4), and criteria for a CMMRD diagnosis (Table 5 and Fig. 1).

Rectangles with rounded corners indicate clinical, genetic, and diagnostic status of the patient prior to and during diagnostic work-up (blue filling) as well as after diagnostic work-up (green, yellow and red filling). Diamonds with blue filling indicate decision points that can either be fulfilled (yes, follow the blue arrow) or not be fulfilled (no, follow the red arrow).

Twelve recommendations for genetic counselling (Table 1b) include recommendations for predictive testing in relatives of CMMRD patients, for prenatal and preimplantation CMMRD testing and for MMR gene analysis in partners of CMMRD and LS patients.

Twenty-nine recommendations for surveillance are presented in Table 1c and summarised in Table 6. They include six general recommendations (recommendations (Rec.) 1–5 and 28), six specific recommendations for brain tumour surveillance by MRI, two for haematological malignancy surveillance, eight for gastro-intestinal surveillance, and five for surveillance in adulthood for other LS-related tumours, such as gynaecological or urinary tract tumours, and breast cancer. Additionally, two recommendations address the place of whole body MRI in CMMRD surveillance. All recommendations contain information on the starting age, the frequency, and modalities of the surveillance.

Four recommendations for quality of life mainly address psychological support and age adapted patient and family education (Table 1d).

Twenty-three recommendations for clinical management consist of general recommendations on malignancy treatment (including radiation therapy and stem cell transplantation; Table 1e). Specific recommendations are given for ICI therapy of high-grade glioma, colorectal cancer, other LS-related and non-LS related malignancies and for chemotherapy of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and leukaemia. Management of polyposis, low-grade glioma, medulloblastoma, suspected tumour relapse and IgG/A production deficits, surveillance during tumour treatment, and colorectal cancer prevention with acetylsalicylic acid are also covered.

Discussion

These are the first comprehensive guidelines addressing the most important aspects of care for CMMRD across five sections: diagnosis, genetic counselling, surveillance, quality of life, and clinical management. Previous guidelines focused only on one or two of these topics, mainly diagnosis and surveillance, and mentioned other aspects of CMMRD care, such as clinical management, genetic counselling, and quality of life, only in their discussions. In the following, evidence for the recommendations given here and their comparison with recommendations in existing guidelines for the diagnosis and surveillance of CMMRD are provided.

Diagnosis

Indications for testing

The recommendations 1–4 and 6 address the question of which children/young adults should be tested for CMMRD. The recommendations 1 and 6 of these guidelines are based on the C4CMMRD guidelines for the clinical indication for CMMRD testing in cancer patients ([15], Table 2) and in children suspected to have sporadic NF1/Legius syndrome without cancer and without an NF1/SPRED1 germline PV after comprehensive genetic analysis ([20], Table 3). While the latter guidelines are included here without any change (Table 3), the C4CMMRD guidelines for the clinical indication for CMMRD testing in cancer patients, a 3-point scoring system (Table 2), have been adapted to include new knowledge. Specifically, two tumour types should now be differently named. CMMRD-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) of the T-cell lineage falls mainly in the entity of T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. Supra-tentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumours no longer exist as a specific tumour type and CMMRD-associated brain tumours previously classified as such fall mainly into the group of diffuse high-grade gliomas. Furthermore, multiple developmental venous anomalies (also known as cerebral venous angiomas) of the brain, which are frequent in CMMRD (73–100% patients) [16, 40, 41] were included as a new feature with two points as DVA are rare (1.6%) in the general paediatric population. Note however, that a single DVA was found in 10% of NF1 patients analysed, most of whom had either low-grade or high-grade gliomas, in 14% of patients with Lynch syndrome and high-grade gliomas, and in 6% of all sporadic patients with high-grade gliomas, while multiple DVA were found in 83% of CMMRD with high-grade gliomas and 3% of the analysed NF1 patients, but in none of the sporadic or Lynch syndrome patients with HGGs [17]. Paediatric systemic lupus erythematosus, which is rare in the general population (prevalence <1/25,000 children), was found in a total of six of more than 200 reported CMMRD patients and is, hence, also significantly overrepresented in CMMRD patients [42, 43]. This feature is newly included with one point. So far, unpublished results of the Gustave Roussy university hospital, which systematically applied the original C4CMMRD criteria, showed that assigning two points to two or more hyperpigmented and/or hypopigmented skin alterations was too inclusive and led to CMMRD testing in many non-CMMRD patients causing often unnecessary anxiety in patients and their families as well as extensive diagnostic effort to refute the diagnosis. This feature was assigned only one point in the revised criteria. However, clinical signs of NF1 and/or ≥4 hyperpigmented and/or hypopigmented skin alterations with a diameter over 1 cm remained weighted with two points. Note that it has been shown in a small number of patients with CMMRD that an NF1 phenotype may result from a (postzygotic) NF1 PV identifiable in blood leukocytes [44, 45]. Therefore, it is advisable to consider CMMRD also in genetically confirmed (mosaic) NF1 patients who have a malignancy that is not typical of NF1, such as a paediatric diffuse high-grade glioma, a T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma or other.

The original C4CMMRD guidelines [15] are widely used and were included also as a diagnostic entry point in recommendations from the international consensus working group on diagnostic criteria for CMMRD, consisting of members of the IRRDC and C4CMMRD [39] and the Pediatric Cancer Working Group of the AACR [29]. A tumour with a high TMB (Rec. 2) or expression loss of one or more of the four MMR proteins in neoplastic and in non-neoplastic cells (Rec. 3) are criteria for CMMRD testing recommended by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer in addition to clinical features covered by the C4CMMRD guidelines [11]. Recommendation 4 accommodates for the identification of a heterozygous (likely) pathogenic variant in one of the MMR genes in a cancer patient aged < 18 years by germline whole exome or whole genome sequencing, which is performed with increasing frequency in paediatric cancer patients [46]. Given that a second PV in the notoriously difficult to analyse PMS2 [47], but also in the other MMR genes, may escape detection by whole exome or whole genome sequencing, such a result should entail CMMRD diagnostic work-up.

Testing strategy and diagnostic criteria

Some aspects of the optimal CMMRD testing strategy (Rec. 7–11) and criteria for a definitive CMMRD diagnosis (recommendations 12–14) have been discussed in previous guidelines [15, 20] and/or formulated into the diagnostic criteria provided in the international consensus working group recommendations [39]. There are several differences in the present recommendations compared to these earlier recommendations. Here, Table 4 lists ancillary tests that can confirm or refute CMMRD if genetic testing is inconclusive. In contrast to the previous recommendations [39], immunohistochemistry of the four MMR proteins is not included as an ancillary test in this list, as this approach can generate both false positive and false negative results and, therefore, is not suitable to confirm or refute CMMRD. An exception is a deceased cancer patient fulfilling one or more criteria for CMMRD testing and for whom no germline DNA is available (Rec. 14). Nonetheless, immunohistochemistry staining of all four MMR proteins in tumour tissue to determine MMR protein expression in neoplastic and in non-neoplastic cells, including tumour infiltrating leukocytes and/or endothelial cells, is recommended wherever possible to gain additional information that can strengthen the evidence for or against a CMMRD diagnosis (Rec. 8). All ancillary assays listed in Table 4 have been evaluated in large cohorts of positive and negative controls. With the exception of the gMSI assay [28], which is insensitive to MSH6-associated CMMRD, all have achieved 100% specificity and sensitivity [22, 24, 26, 27]. A positive result from any of these single ancillary tests (including the gMSI assay) can confirm a CMMRD diagnosis when genetic testing is inconclusive, provided that the assay has been thoroughly evaluated in the laboratory. This is independent of whether a malignancy defined by the international consensus working group [39] as a “CMMRD hallmark cancer” is present or not. Here, it is recommended that in patients in whom only one or no MMR variant classified as (L)PV or VUS has been identified, transcript analysis should show either faulty splicing or reduced expression of the wild-type MMR allele(s) in addition to a positive ancillary test result for a CMMRD diagnosis to be made (Rec. 12, Table 5, Fig. 1). In contrast to the international consensus working group recommendations [39], the present criteria make no distinction between a definite and a likely diagnosis. They stress that any testing strategy should aim to come to a definite diagnosis that either confirms or refutes CMMRD in the patient and to identify the causative MMR gene variants (Rec. 7). Therefore, the laboratory performing genetic CMMRD testing should be able to: (i) offer transcript analysis of all four MMR genes, (ii) apply assays that circumvent potential diagnostic pitfalls that result from the high homology of PMS2 and its pseudogene PMS2CL and (iii) use one or more validated ancillary assay(s) available either in house or by partnership with a different laboratory (Rec. 9–11). Cancer patients in whom the suspected diagnosis of CMMRD cannot be confirmed should probably be tested for germline POLE and POLD1 exonuclease domain variants (Rec. 13), since specific heterozygous POLE germline PV as well as a digenic combination of a heterozygous germline POLE or POLD1 PV and a heterozygous germline MMR gene PV have been shown to cause a phenotype reminiscent of CMMRD [48, 49].

Genetic counselling

There is discussion of whether LS carriers of reproductive age should be informed about the risk of CMMRD syndrome for their offspring and of the possibility of testing their partner before pregnancy. This is particularly relevant for the PMS2 gene since, based on data from first degree relatives in the Colon Cancer Family Registry, the frequency of PMS2 PV carriers in the general population is 1 in 714 and they may not present as LS due to the low penetrance of PMS2 PV in the heterozygous state [21]. Therefore, the a priori risk for a PMS2-associated LS carrier to give birth to a child affected with CMMRD is estimated to be 1/2856 (1/4 × 1/714) and for a PMS2-associated CMMRD patient it is estimated to be 1/1428 (1/2 × 1/714). These risks are higher in cases of consanguinity of the couple or in populations with founder effects. Currently, there are no published recommendations regarding whether to test the partner of a Lynch or CMMRD syndrome patient outside the context of consanguinity or founder effect. This question was discussed at the C4CMMRD Consortium meeting in November 2022 in Paris without reaching a consensus. Indeed, such a recommendation depends on the possibilities of access to genetic testing in each country (costs, prescription habits, and access to genetic counselling). Furthermore, it should be considered that a complete analysis of an MMR gene in the partner could reveal a VUS making genetic counselling complicated and that comprehensive PMS2 analysis remains complex with limited availability. The recommendations given here (Rec. 9–11) rely entirely on the Delphi process, which reached a consensus that genetic testing of MMR genes should not be offered to partners of an LS carrier in the absence of consanguinity, the partner belonging to a population with a known founder variant, or the partner having a family history suggestive of LS. However, testing should be offered to the partner of an LS carrier in the presence of any of these three criteria, as well as to partners of CMMRD patients.

Surveillance

It is widely accepted that CMMRD patients and their parents should be educated about tumour risks associated with CMMRD and about symptoms related to the main tumours. We recommend a clinical examination for children and adults with CMMRD every 6 months and pros and cons of more specific surveillance modalities should be discussed with the CMMRD patient and/or their parents so that they, together with the clinician, can make an informed joint decision to participate in a surveillance program. A greater awareness of being at high risk for developing cancers may increase psychological distress, especially before and after surveillance examinations. In addition, examinations may reveal small lesions of unknown significance in asymptomatic patients for which the only management option is monitoring at a short follow-up interval. Since such situations may increase anxiety, it would be important to provide psycho-oncological support at any time during cancer surveillance and treatment (Table 1d, Rec. 2).

Previous surveillance protocols for CMMRD patients were provided by the C4CMMRD consortium [8], the Pediatric Cancer Working Group of the AACR [29] and the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer [11]. Observational prospective studies in individuals with CMMRD conducted by the European C4CMMRD consortium and the IRRDC have demonstrated a survival benefit for those individuals with CMMRD who undergo surveillance compared to those who do not [12, 30]. Both studies show that surveillance of the digestive tract and the brain led to early detection of tumours supporting the effectiveness of the suggested surveillance measures [12, 30]. Haematological malignancies were mainly discovered incidentally and between follow-up examinations. Hence, monitoring for haematological malignancies has not proven to be effective. Considering the rapid tumour growth of paediatric NHL, screening requires short intervals between evaluations, which should be performed at least every 3 months. In addition, abdominal ultrasound is not able to detect T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma, which is the most frequent NHL subtype in CMMRD, located in the mediastinum in most cases. Regular chest X-rays are not recommended for screening because of the potential genotoxic effects of repeated exposure to X-rays. While blood count may be useful in cases of bone marrow infiltration, it has limited value in ALL or NHL surveillance [50]. Although regular blood sampling for detection of circulating T-cell rearrangement may be a potential option for early diagnosis of T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma, its effectiveness in CMMRD is unknown and needs further evaluation in research studies. Based on these observations and previously discussed considerations [51], we recommend only clinical monitoring every 6 months (Rec. 5) and, in contrast to previous guidelines, do not recommend abdominal ultrasound or systematic blood count (Rec. 12-13).

Both the IRRDC study and the C4CMMRD study evaluating the previous surveillance guidelines support a six-month interval for brain MRI. Before the introduction of surveillance programmes, most CMMRD-patients did not reach adulthood, therefore studies assessing the brain tumour risk in an adult population are not available. Nonetheless, given their already intensive surveillance program, the recommendation to perform annual screening in adults from the age of 20 years by brain imaging achieved consensus (Rec. 8).

All expert groups including the present one agree on endoscopy of the digestive tract as the most effective intervention facilitating early cancer detection and polyp removal before progression into cancer [12]. The progression of adenomas to malignancy in CMMRD is one of the most rapid of any inherited colorectal cancer syndrome [12, 31], and surveillance intervals should, therefore, not exceed 1 year increasing to an approximately 6-months interval once polyps are detected (Rec. 18, 20). Given the diagnoses of small bowel and stomach cancers in CMMRD patients as young as 9 years, it is recommended video capsule endoscopy (VCE) and gastroscopic surveillance are started at the same time as colonoscopy, which is recommended to start at 6 years (Rec. 15, 18, 21). To date there is no data about value of MRI of the small bowel in CMMRD patients but this exam could be considered in combination with push enteroscopy with careful inspection of the ampullary region because small bowel neoplasms are often proximally located and may be missed by VCE ([52], Rec. 16).

The incidence of gynaecological and urinary tract tumours in CMMRD is unknown, especially as the majority of these tumours in CMMRD have been reported at an age that most CMMRD patients do not reach. Expert advice during the Delphi process was to not recommend annual urine cytology and urine dipstick to CMMRD patients because their benefit in LS patients has not been demonstrated (Rec. 24). The same decision was made for endometrial biopsy, which significantly adds to the burden of surveillance by the pain it causes. Instead, it is recommended that abdomino-pelvic ultrasound, clinical examination, and transvaginal ultrasound are performed (Rec. 22, 25).

We considered the current data to be insufficient to draw conclusions on the effectiveness of whole body MRI (WBMRI) [12]. As the tumour spectrum in CMMRD is different, WBMRI may not have the same efficacy as in Li-Fraumeni syndrome, where sarcomas are more frequent [53,54,55]. Thus, surveillance by WBMRI is included as optional in the recommendations with the recommendation to offer it at least once to detect malformations and low-grade tumours requiring resection or adapted surveillance (Rec. 27–29). In addition, we encourage collecting data on WBMRI so that its benefit in CMMRD can be assessed. As brain tumours are the major oncological risk in CMMRD patients, WBMRI should not replace specific brain imaging.

Based on data of the 64 low-grade tumours detected, Durno and colleagues [12] found that the cumulative likelihood of transformation to high-grade cancer was 81% for gastrointestinal cancers within 8 years and 100% for gliomas within 6 years. Hence, we recommend that resection or specific surveillance of low-grade lesions should be offered to CMMRD patients (Rec 28).

Clinical management

To date, surgery is still the mainstay for resectable high-grade glioma. It has been shown that recurrent glioblastomas after temozolomide treatment frequently exhibit a hypermutated phenotype with defective MMR [56] confirming previous preclinical evidence that MMR defects are a major mechanism of resistance to temozolomide [38]. Taken together, temozolomide is no longer recommended in CMMRD patients (Rec. 6). Given the high response rate to ICI in patients with CMMRD [35,36,37], including ICI in the front-line treatment of patients with high grade glioma should be considered (Rec. 7).

Even though MMR deficient cells have been shown to have a certain degree of tolerance to thiopurines in vitro, clinical data obtained in a large series of CMMRD-associated NHL do not demonstrate an increased risk of treatment failure in CMMRD patients treated with the current standard regimens as compared to patients with sporadic NHL [57]. The treatment approach for CMMRD NHL and leukaemia should probably not differ from treatment of sporadic cases (Rec. 10, 12). Also, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation seems feasible [14] (Rec. 5).

ICI have shown their efficacy in MSI tumours and now represent the standard of care for metastatic and advanced colorectal cancer patients with LS [58]. Therefore, it is recommended that management of cancers of the LS spectrum in a CMMRD patient follow treatment guidelines designed for patients with LS associated tumours, and that immunotherapy should be used as front-line treatment of large, unresectable, or metastatic colorectal tumours in a CMMRD patient (Rec. 13-14). Decisions regarding the management of colorectal polyposis in these patients should take several considerations into account. An early and extensive surgical management, such as total colectomy, might appear indicated due to the much faster progression from adenoma to carcinoma in CMMRD than in other adenomatous polyposis syndromes. However, it should also be considered that in CMMRD (i) the presence of multiple polyps is common, but usually in numbers manageable by endoscopic resection, (ii) immunotherapy is an effective treatment option for carcinomas of the digestive tract, (iii) extensive colonic surgery has an adverse impact on quality of life in these young patients, and (iv) the poor prognosis of these patients is mainly due to other, particularly brain, tumours. Taken together, we do not recommend specific and/or early digestive surgical management for CMMRD patients. Even though CMMRD-associated polyps more frequently show high-grade dysplasia, as in other adenomatous polyposis syndromes [59, 60], surgical decisions should be mainly guided by whether or not the polyposis can be controlled endoscopically (Rec 17), considering endoscopic interventions every 6 months if needed (surveillance Rec 18).

A potential preventive effect of immunotherapy or acetylsalicylic acid on polyposis development is uncertain. There is currently insufficient evidence in the literature to recommend the use for chemoprevention, though the potential benefits and side effects of preventive treatment with acetylsalicylic acid should probably be discussed with CMMRD patients (Rec. 22).

Considering the high incidence of multiple tumours in CMMRD patients, we recommend separate sampling and molecular analysis of synchronous tumours as they might be distinct entities. Cancer surveillance should be performed at the time of diagnosis as well as during and after the period of cancer treatment (Rec. 18) and in case of suspicion of a relapse, it is crucial to consider the possibility of a second primary disease rather than a relapse and to perform molecular analysis of samples at initial diagnosis and relapse to make an accurate diagnosis (Rec. 19-20).

Future research

Being so rare, characterisation of CMMRD pathology and clinical course is difficult and requires concerted, international efforts. Therefore, a general priority for future research is to maintain and expand patient registries as well as the clinical and academic networks around CMMRD.

Currently, there are only a few retrospective studies that can provide empirical evidence for the prevalence of CMMRD among different cancer patient populations (Supp. Tables S1 & S7 in [61]) [62,63,64]. These studies rely largely on genetic CMMRD diagnosis using high-throughput sequencing methods and are associated with some uncertainties. Prospective screening for CMMRD in relevant patient cohorts (paediatric high-grade glioma or T-lymphoblastic lymphoma patients, children suspected of sporadic NF1, etc.) using scalable, highly reliable, and low-cost ancillary assays [24,25,26,27], should improve frequency estimation which will have an impact on future guidelines for CMMRD diagnosis. Although associated with more limitations, tumour-based molecular screening, e.g. by immunohistochemistry analysis of MMR protein expression [65] and analyses of tumour mutation burden and mutational signatures [61, 66], could also be used to identify CMMRD patients in relevant patient cohorts. Such studies would also lay the basis for an evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of the clinical indication criteria for CMMRD in cancer patients (Table 2) to assess their efficacy and potential weaknesses for refinement.

As has been seen in other cancer syndromes, the ascertainment bias affecting retrospective studies of “familial cases”, if not corrected by dedicated statistical methods, may lead to an over-estimation of cancer risks associated with CMMRD. Molecular screening for CMMRD in cancer patient cohorts recruited with limited clinical and/or familial selection criteria may identify more CMMRD patients and provide less biased estimates of cancer risks associated with CMMRD, which may have implications for future diagnosis and management guidelines. Further exploration of MMR genotype-phenotype correlations including characterization of hypomorphic variants [6, 7] could facilitate better risk stratification, provide general insight into MMR function, and tailor future recommendations to patients’ genotypes.

Although cancer surveillance in CMMRD has been shown to improve survival [12, 30], further assessment of its efficacy and impact is needed. In particular, evaluation of the clinical utility of WBMRI in prospective studies is needed. The improved overall survival of CMMRD patients due to surveillance and therapeutic advancements would mean that more patients will reach an older age. This has implications for both our understanding of the CMMRD phenotype and its management. In particular, the CMMRD cancer spectrum may change with age and surveillance protocols may need to be adapted accordingly. Studies on the acceptability and psychological impact of, as well as long-term adherence to surveillance interventions are currently lacking.

CMMRD cancer risk could also be managed through prevention. Immune-based prophylaxis may provide a novel approach to CMMRD cancer prevention. Vaccines have been developed based on frameshift peptides associated with MMR deficient cancers in humans, and have been shown to be safe in a phase I/IIa clinical trial [67] and to induce an immune response [67, 68]. Therefore, vaccination of CMMRD patients with frameshift peptide neoantigens could be trialled in the future. Alternatively, daily acetylsalicylic acid intake approximately halved the incidence of colorectal carcinomas in LS carriers in the CAPP2 randomised control trial [69] and could be beneficial to CMMRD patients [70]. However, there is currently no strong evidence to support a reduction of cancer incidence by acetylsalicylic acid or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in CMMRD, and further studies are needed.

The loss of MMR function in CMMRD tumours makes them resistant to certain chemotherapies, whilst sensitising them to ICI. CMMRD tumours, therefore, may require specific management. Mechanisms of therapy resistance also require exploration. Research in this area is ongoing and our understanding is rapidly changing. Promising biomarkers for ICI response include TMB, with higher TMB being predictive of positive ICI response among MMR deficient metastatic colorectal carcinomas [71], and measures of intra-tumoural immune activity, such as Immunoscore® [72]. Studies of biomarkers of ICI response and resistance in the context of different CMMRD tumours are needed.

Studies of CMMRD tumourigenesis pathways will improve our understanding of the CMMRD phenotype and allow us to optimise management. Systematic biobanking of neoplastic tissues will be particularly useful to answer these questions. Model systems, such as cell lines, organoids, and mice, will also be helpful.

Conclusion

Although these guidelines are written primarily for geneticists and paediatric haemato-oncologists, they can also be used by other physicians, patients or other interested parties. The recommendations given here are statements to support decision making, based on systematically evaluated evidence for a specified clinical setting. Whilst these clinical guidelines are based on the latest published evidence, care of each individual remains primarily the responsibility of their treating medical professionals. Decisions for care should always be based on the needs, preferences and circumstances of each patient. These clinical guidelines should support clinical decision making, but never replace clinical professionals.

References

Zou X, Koh GCC, Nanda AS, Degasperi A, Urgo K, Roumeliotis TI, et al. A systematic CRISPR screen defines mutational mechanisms underpinning signatures caused by replication errors and endogenous DNA damage. Nat Cancer. 2021;2:643–57.

Dominguez-Valentin M, Sampson JR, Seppala TT, Ten Broeke SW, Plazzer JP, Nakken S, et al. Cancer risks by gene, age, and gender in 6350 carriers of pathogenic mismatch repair variants: findings from the Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database. Genet Med. 2020;22:15–25.

Ricciardone MD, Ozcelik T, Cevher B, Ozdag H, Tuncer M, Gurgey A, et al. Human MLH1 deficiency predisposes to hematological malignancy and neurofibromatosis type 1. Cancer Res. 1999;59:290–3.

Wang Q, Lasset C, Desseigne F, Frappaz D, Bergeron C, Navarro C, et al. Neurofibromatosis and early onset of cancers in hMLH1-deficient children. Cancer Res. 1999;59:294–7.

Bruekner SR, Pieters W, Fish A, Liaci AM, Scheffers S, Rayner E, et al. Unexpected moves: a conformational change in MutSalpha enables high-affinity DNA mismatch binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:1173–88.

Li L, Hamel N, Baker K, McGuffin MJ, Couillard M, Gologan A, et al. A homozygous PMS2 founder mutation with an attenuated constitutional mismatch repair deficiency phenotype. J Med Genet. 2015;52:348–52.

Gallon R, Brekelmans C, Martin M, Bours V, Schamschula E, Amberger A, et al. Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency mimicking Lynch syndrome is associated with hypomorphic mismatch repair gene variants. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2024;8:119.

Vasen HF, Ghorbanoghli Z, Bourdeaut F, Cabaret O, Caron O, Duval A, et al. Guidelines for surveillance of individuals with constitutional mismatch repair-deficiency proposed by the European Consortium “Care for CMMR-D” (C4CMMR-D). J Med Genet. 2014;51:283–93.

Ercan AB, Aronson M, Fernandez NR, Chang Y, Levine A, Liu ZA, et al. Clinical and biological landscape of constitutional mismatch-repair deficiency syndrome: an International Replication Repair Deficiency Consortium cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2024;25:668–82.

Wimmer K, Rosenbaum T, Messiaen L. Connections between constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome and neurofibromatosis type 1. Clin Genet. 2017;91:507–19.

Durno C, Boland CR, Cohen S, Dominitz JA, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, et al. Recommendations on Surveillance and Management of Biallelic Mismatch Repair Deficiency (BMMRD) Syndrome: A Consensus Statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1605–14.

Durno C, Ercan AB, Bianchi V, Edwards M, Aronson M, Galati M, et al. Survival Benefit for Individuals With Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency Undergoing Surveillance. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:2779–90.

Lavoine N, Colas C, Muleris M, Bodo S, Duval A, Entz-Werle N, et al. Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome: clinical description in a French cohort. J Med Genet. 2015;52:770–8.

Ripperger T, Schlegelberger B. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoma in the context of constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 2016;59:133–42.

Wimmer K, Kratz CP, Vasen HF, Caron O, Colas C, Entz-Werle N, et al. Diagnostic criteria for constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome: suggestions of the European consortium ‘care for CMMRD’ (C4CMMRD). J Med Genet. 2014;51:355–65.

Shiran SI, Ben-Sira L, Elhasid R, Roth J, Tabori U, Yalon M, et al. Multiple Brain Developmental Venous Anomalies as a Marker for Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency Syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39:1943–6.

Raveneau M, Guerrini-Rousseau L, Levy R, Roux C, Bolle S, Doz F, et al. Specific brain MRI features of constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome in children with high-grade gliomas. Eur Radiol. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-024-10885-3. Online ahead of print.

Tesch VK, H IJ, Raicht A, Rueda D, Dominguez-Pinilla N, Allende LM, et al. No Overt Clinical Immunodeficiency Despite Immune Biological Abnormalities in Patients With Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1506.

Perez-Valencia JA, Gallon R, Chen Y, Koch J, Keller M, Oberhuber K, et al. Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency is the diagnosis in 0.41% of pathogenic NF1/SPRED1 variant negative children suspected of sporadic neurofibromatosis type 1. Genet Med. 2020;22:2081–8.

Suerink M, Ripperger T, Messiaen L, Menko FH, Bourdeaut F, Colas C, et al. Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency as a differential diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1: consensus guidelines for testing a child without malignancy. J Med Genet. 2019;56:53–62.

Win AK, Jenkins MA, Dowty JG, Antoniou AC, Lee A, Giles GG, et al. Prevalence and Penetrance of Major Genes and Polygenes for Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2017;26:404–12.

Bodo S, Colas C, Buhard O, Collura A, Tinat J, Lavoine N, et al. Diagnosis of Constitutional Mismatch Repair-Deficiency Syndrome Based on Microsatellite Instability and Lymphocyte Tolerance to Methylating Agents. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1017–29.e3.

Chung J, Maruvka YE, Sudhaman S, Kelly J, Haradhvala NJ, Bianchi V, et al. DNA Polymerase and Mismatch Repair Exert Distinct Microsatellite Instability Signatures in Normal and Malignant Human Cells. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:1176–91.

Chung J, Negm L, Bianchi V, Stengs L, Das A, Liu ZA, et al. Genomic Microsatellite Signatures Identify Germline Mismatch Repair Deficiency and Risk of Cancer Onset. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:766–77.

Gallon R, Muhlegger B, Wenzel SS, Sheth H, Hayes C, Aretz S, et al. A sensitive and scalable microsatellite instability assay to diagnose constitutional mismatch repair deficiency by sequencing of peripheral blood leukocytes. Hum Mutat. 2019;40:649–55.

Gallon R, Phelps R, Hayes C, Brugieres L, Guerrini-Rousseau L, Colas C, et al. Constitutional Microsatellite Instability, Genotype, and Phenotype Correlations in Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:579–92e8.

Gonzalez-Acosta M, Marin F, Puliafito B, Bonifaci N, Fernandez A, Navarro M, et al. High-sensitivity microsatellite instability assessment for the detection of mismatch repair defects in normal tissue of biallelic germline mismatch repair mutation carriers. J Med Genet. 2020;57:269–73.

Ingham D, Diggle CP, Berry I, Bristow CA, Hayward BE, Rahman N, et al. Simple detection of germline microsatellite instability for diagnosis of constitutional mismatch repair cancer syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:847–52.

Tabori U, Hansford JR, Achatz MI, Kratz CP, Plon SE, Frebourg T, et al. Clinical Management and Tumor Surveillance Recommendations of Inherited Mismatch Repair Deficiency in Childhood. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:e32–e7.

Ghorbanoghli Z, van Kouwen M, Versluys B, Bonnet D, Devalck C, Tinat J, et al. High yield of surveillance in patients diagnosed with constitutional mismatch repair deficiency. J Med Genet. 2023;60:679–84.

Shlien A, Campbell BB, de Borja R, Alexandrov LB, Merico D, Wedge D, et al. Combined hereditary and somatic mutations of replication error repair genes result in rapid onset of ultra-hypermutated cancers. Nat Genet. 2015;47:257–62.

Andrianova MA, Chetan GK, Sibin MK, McKee T, Merkler D, Narasinga RK, et al. Germline PMS2 and somatic POLE exonuclease mutations cause hypermutability of the leading DNA strand in biallelic mismatch repair deficiency syndrome brain tumours. J Pathol. 2017;243:331–41.

Haradhvala NJ, Kim J, Maruvka YE, Polak P, Rosebrock D, Livitz D, et al. Distinct mutational signatures characterize concurrent loss of polymerase proofreading and mismatch repair. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1746.

Sha D, Jin Z, Budczies J, Kluck K, Stenzinger A, Sinicrope FA. Tumor Mutational Burden as a Predictive Biomarker in Solid Tumors. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:1808–25.

Das A, Sudhaman S, Morgenstern D, Coblentz A, Chung J, Stone SC, et al. Genomic predictors of response to PD-1 inhibition in children with germline DNA replication repair deficiency. Nat Med. 2022;28:125–35.

Henderson JJ, Das A, Morgenstern DA, Sudhaman S, Bianchi V, Chung J, et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibition as Single Therapy for Synchronous Cancers Exhibiting Hypermutation: An IRRDC Study. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2100286.

Das A, Fernandez NR, Levine A, Bianchi V, Stengs LK, Chung J, et al. Combined Immunotherapy Improves Outcome for Replication-Repair-Deficient (RRD) High-Grade Glioma Failing Anti-PD-1 Monotherapy: A Report from the International RRD Consortium. Cancer Discov. 2024;14:258–73.

Gan T, Wang Y, Xie M, Wang Q, Zhao S, Wang P, et al. MEX3A Impairs DNA Mismatch Repair Signaling and Mediates Acquired Temozolomide Resistance in Glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2022;82:4234–46.

Aronson M, Colas C, Shuen A, Hampel H, Foulkes WD, Baris Feldman H, et al. Diagnostic criteria for constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD): recommendations from the international consensus working group. J Med Genet. 2022;59:318–27.

Guerrini-Rousseau L, Varlet P, Colas C, Andreiuolo F, Bourdeaut F, Dahan K, et al. Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency-associated brain tumors: report from the European C4CMMRD consortium. Neuro Oncol Adv. 2019;1:vdz033.

Kerpel A, Yalon M, Soudack M, Chiang J, Gajjar A, Nichols KE, et al. Neuroimaging Findings in Children with Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency Syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41:904–10.

Vassantachart JM, Zacher NC, Teng JMC. Eruptive nevi in a patient with constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD). Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39:91–3.

Toledano H, Orenstein N, Sofrin E, Ruhrman-Shahar N, Amarilyo G, Basel-Salmon L, et al. Paediatric systemic lupus erythematosus as a manifestation of constitutional mismatch repair deficiency. J Med Genet. 2020;57:505–8.

Alotaibi H, Ricciardone MD, Ozturk M. Homozygosity at variant MLH1 can lead to secondary mutation in NF1, neurofibromatosis type I and early onset leukemia. Mutat Res. 2008;637:209–14.

Guerrini-Rousseau L, Pasmant E, Muleris M, Abbou S, Adam-De-Beaumais T, Brugieres L, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 mosaicism in patients with constitutional mismatch repair deficiency. J Med Genet. 2024;61:158–62.

Kratz CP, Smirnov D, Autry R, Jager N, Waszak SM, Grosshennig A, et al. Heterozygous BRCA1 and BRCA2 and Mismatch Repair Gene Pathogenic Variants in Children and Adolescents With Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114:1523–32.

Mandelker D, Schmidt RJ, Ankala A, McDonald Gibson K, Bowser M, Sharma H, et al. Navigating highly homologous genes in a molecular diagnostic setting: a resource for clinical next-generation sequencing. Genet Med. 2016;18:1282–9.

Sehested A, Meade J, Scheie D, Ostrup O, Bertelsen B, Misiakou MA, et al. Constitutional POLE variants causing a phenotype reminiscent of constitutional mismatch repair deficiency. Hum Mutat. 2022;43:85–96.

Schamschula E, Kinzel M, Wernstedt A, Oberhuber K, Gottschling H, Schnaiter S, et al. Teenage-Onset Colorectal Cancers in a Digenic Cancer Predisposition Syndrome Provide Clues for the Interaction between Mismatch Repair and Polymerase delta Proofreading Deficiency in Tumorigenesis. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1350.

Porter CC, Druley TE, Erez A, Kuiper RP, Onel K, Schiffman JD, et al. Recommendations for Surveillance for Children with Leukemia-Predisposing Conditions. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:e14–22.

Westdorp H, Kolders S, Hoogerbrugge N, de Vries IJM, Jongmans MCJ, Schreibelt G. Immunotherapy holds the key to cancer treatment and prevention in constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD) syndrome. Cancer Lett. 2017;403:159–64.

Shimamura Y, Walsh CM, Cohen S, Aronson M, Tabori U, Kortan PP, et al. Role of video capsule endoscopy in patients with constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD) syndrome: report from the International CMMRD Consortium. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E1037–43.

Ballinger ML, Ferris NJ, Moodie K, Mitchell G, Shanley S, James PA, et al. Surveillance in Germline TP53 Mutation Carriers Utilizing Whole-Body Magnetic Resonance Imaging. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1735–6.

Frebourg T, Bajalica Lagercrantz S, Oliveira C, Magenheim R, Evans DG. European Reference Network G. Guidelines for the Li-Fraumeni and heritable TP53-related cancer syndromes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020;28:1379–86.

Tewattanarat N, Junhasavasdikul T, Panwar S, Joshi SD, Abadeh A, Greer MLC, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of imaging approaches for early tumor detection in children with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Pediatr Radio. 2022;52:1283–95.

Touat M, Li YY, Boynton AN, Spurr LF, Iorgulescu JB, Bohrson CL, et al. Mechanisms and therapeutic implications of hypermutation in gliomas. Nature. 2020;580:517–23.

Rigaud C, Forster VJ, Al-Tarrah H, Attarbaschi A, Bianchi V, Burke A, et al. Comprehensive analysis of constitutional mismatch repair deficiency-associated non-Hodgkin lymphomas in a global cohort. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2024:e31302. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.31302. Online ahead of print.

Jin Z, Sinicrope FA. Mismatch Repair-Deficient Colorectal Cancer: Building on Checkpoint Blockade. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:2735–50.

Hyer W, Cohen S, Attard T, Vila-Miravet V, Pienar C, Auth M, et al. Management of Familial Adenomatous Polyposis in Children and Adolescents: Position Paper From the ESPGHAN Polyposis Working Group. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;68:428–41.

van Leerdam ME, Roos VH, van Hooft JE, Balaguer F, Dekker E, Kaminski MF, et al. Endoscopic management of Lynch syndrome and of familial risk of colorectal cancer: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2019;51:1082–93.

Gröbner SN, Worst BC, Weischenfeldt J, Buchhalter I, Kleinheinz K, Rudneva VA, et al. The landscape of genomic alterations across childhood cancers. Nature. 2018;555:321–7.

Attarbaschi A, Carraro E, Ronceray L, Andres M, Barzilai-Birenboim S, Bomken S, et al. Second malignant neoplasms after treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma-a retrospective multinational study of 189 children and adolescents. Leukemia. 2021;35:534–49.

de Voer RM, Diets IJ, van der Post RS, Weren RDA, Kamping EJ, de Bitter TJJ, et al. Clinical, Pathology, Genetic, and Molecular Features of Colorectal Tumors in Adolescents and Adults 25 Years or Younger. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:1642–51.e8.

Kroeze E, Weijers DD, Hagleitner MM, de Groot-Kruseman HA, Jongmans MCJ, Kuiper RP, et al. High Prevalence of Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency in a Pediatric T-cell Lymphoblastic Lymphoma Cohort. Hemasphere. 2022;6:e668.

Carrato C, Sanz C, Munoz-Marmol AM, Blanco I, Pineda M, Del Valle J, et al. The Challenge of Diagnosing Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency Syndrome in Brain Malignancies from Young Individuals. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:4629.

Thatikonda V, Islam SMA, Autry RJ, Jones BC, Grobner SN, Warsow G, et al. Comprehensive analysis of mutational signatures reveals distinct patterns and molecular processes across 27 pediatric cancers. Nat Cancer. 2023;4:276–89.

Kloor M, Reuschenbach M, Pauligk C, Karbach J, Rafiyan MR, Al-Batran SE, et al. A Frameshift Peptide Neoantigen-Based Vaccine for Mismatch Repair-Deficient Cancers: A Phase I/IIa Clinical Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:4503–10.

Leoni G, D’Alise AM, Cotugno G, Langone F, Garzia I, De Lucia M, et al. A Genetic Vaccine Encoding Shared Cancer Neoantigens to Treat Tumors with Microsatellite Instability. Cancer Res. 2020;80:3972–82.

Burn J, Sheth H, Elliott F, Reed L, Macrae F, Mecklin JP, et al. Cancer prevention with aspirin in hereditary colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome), 10-year follow-up and registry-based 20-year data in the CAPP2 study: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1855–63.

Leenders E, Westdorp H, Bruggemann RJ, Loeffen J, Kratz C, Burn J, et al. Cancer prevention by aspirin in children with Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency (CMMRD). Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26:1417–23.

Schrock AB, Ouyang C, Sandhu J, Sokol E, Jin D, Ross JS, et al. Tumor mutational burden is predictive of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in MSI-high metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1096–103.

Hijazi A, Antoniotti C, Cremolini C, Galon J. Light on life: immunoscore immune-checkpoint, a predictor of immunotherapy response. Oncoimmunology. 2023;12:2243169.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Manon Engels and Jurriaan Hölzenspies for logistic support, coordination of the guideline committee meetings and facilitating the guideline development process as well as SQ.RT for providing a literature review at the onset of the development of this guideline. The authors also acknowledge their colleagues from the ERN GENTURIS and from the C4CMMRD consortium for fruitful discussions and suggestions. A special thanks to all the (external) experts who participated in the modified Delphi survey (in alphabetical order): Munaza Ahmed1, Violetta Anastasiadou2, Andishe Attarbaschi3, Stéphanie Baert-Desurmont4,5, Patrick Benusiglio6, Bruno Buecher7, Veronica Biassoni8, Ignacio Blanco9, Franck Bourdeaut10, Carole Corsini11, Karin Dahan12, Bianca DeSouza 13, Nerea Dominguez-Pinilla14, Natacha Entz-Werle15, D. Gareth Evans16, Maurizio Genuardi17,18, Anne-Marie A. Gerdes19, Luis I. Gonzalez-Granado20, Hector S. Hernandez21, Yvette van Ierland22, Danuta Januszkiewicz-Lewandowska23, Joost L.M. Jongen24, Tiina Kahre25, Evaggelia Karaoli26, John-Paul Kilday27, Christof Kramm28, Andreas Laner29, Eric Legius30, Jan L.C. Loeffen31, Angela Mastronuzzi32, Kevin Mohanan33, Martine Muleris34, Fátima M. Nieto35, Rianne Oostenbrink36,37, Enrico Opocher38, Marta Pineda39, Anna Poluha40, Vita Ridola41, Tim Ripperger42, Jose Manuel Sánchez-Zapardiel43, Astrid M. Sehested44, Markus G. Seidel45, Irene Slavc46, Verena Steinke-Lange29, Cécile Talbotec47, Julie Tinat48, Marc Tischkowitz49, Pascale Varlet50, Marco Vitellaro51, Karin Wadt52, Anja Wagner22, Qing Wang53, and Emma R. Woodward54.

1Department of Clinical Genetics, Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, UK. 2Karaiskaki Foundation, Nicosia, Cyprus. 3St. Anna children’s hospital, Vienna, Austria. 4Department of Genetics, Rouen University Hospital, Rouen, France. 5Inserm U1245, Normandie University, UNIROUEN, Normandy Centre for Genomic and Personalized Medicine, Rouen, France. 6Department of Medical Genetics, Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital and Sorbonne University, Paris, France. 7Department of Genetics, Institut Curie, Paris, France. 8Pediatric Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, Italy. 9Clinical Genetics Department, Hospital Germans Trias I Pujol, Badalona, Spain. 10SIREDO pediatric cancer center, Institut Curie, Paris, France. 11Department of Cancer Genetics, CHU Montpellier, University of Montpellier, Montpellier, France. 12Institut de Pathologie et de Génétique, Charleroi, Belgium. 13Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust; Northwest Thames Regional Genetics Service, London, UK. 14Pediatrics Service, Hematology and Oncology Unit, Hospital 12 de octubre,, Madrid, Spain. 15Pédiatrie Onco-Hématologie - Pédiatrie III - CHRU Hautepierre, Strasbourg, France. 16The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK. 17Dipartimento di Scienze della Vita e Sanità Pubblica, Università cattolica del sacroCuore, Rome, Italy. 18UOC Genetica Medica, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy. 19Department Of Genetics, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark. 20Department of Paediatrics, Hospital 12 de octubre, Complutense University, School of Medicine, Madrid, Spain. 21Department of Pediatric Oncology, Sant Joan de Deu Hospital, Barcelona, Spain. 22Department of Clinical Genetics, ErasmusMC, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. 23Department of Pediatric Oncology, Hematology and Transplantology, Poznan University of Sciences, Poznan, Poland. 24Department of Neurology, ErasmusMC, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. 25Department of Laboratory Genetics, Genetics and Personalized Medicine Clinic, Tartu University Hospital, Tartu, Estonia. 26Department of Pediatric Oncology and Haematology, Archbishop Makarios III Hospital, Nicosia, Cyprus. 27Department of Paediatric Oncology, Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, Manchester, UK. 28Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Division of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, University Medical Center Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany. 29MGZ – Medical Genetics Center, Munich, Germany. 30Centre for Human Genetics, University Hospital Leuven, Leuven, Belgium. 31Princess Maxima Centre for Paediatric Oncology, Utrecht, Netherlands. 32Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, IRCCS Istituto Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù, Rome, Italy. 33Centre for Familial Intestinal Cancer, St Mark’s Hospital, London, UK. 34Inserm UMR-S938, centre de recherche Saint-Antoine, Paris, France. 35Hereditary Cancer Group, Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute, (IDIBELL), Barcelona, Spain. 36Department of General Paediatrics, ErasmusMC-Sophia, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. 37ENCORE-NF1 Expertise Center, ErasmusMC-Sophia, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. 38Pediatric Hematology, Oncology and Stem Cell Transplant Division, Padua University Hospital, Padua, Italy. 39Catalan Institute of Oncology, IDIBELL, Barcelona, Spain. 40Department of Clinical Genetics Uppsala University Hospital, Institute of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology, Uppsala University Sweden. 41Department of Pediatric Oncology, Mitera Children’s Hospital, Athens, Greece. 42Department of Human Genetics, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany. 43Hereditary Cancer Laboratory, Hospital 12 de octubre, Madrid, Spain. 44Department of Paediatrics, Righospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark. 45Division of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology and Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria. 46Department of Pediatrics, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. 47Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Hospital Necker Enfants Malades, Paris, France. 48Génétique Médicale, CHU Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France. 49Department of Medical Genetics, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. 50CHU Paris Site Sainte-Anne, Paris, France. 51Hereditary Digestive Tract Tumor Unit - Department of Surgery - Fondazione IRCCS Instituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, Italy. 52Department of Clinical Genetics and Department of Medical Science, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark. 53Laboratory of Constitutional Genetics for Frequent Cancer HCL-CLB, Centre Léon Bérard, Lyon, France. 54Manchester Centre for Genomic Medicine, Manchester, UK.

Funding

This guideline has been supported by the European Reference Network on Genetic Tumour Risk Syndromes (ERN GENTURIS). ERN GENTURIS is funded by the European Union. For more information about the ERNs and the EU health strategy, please visit http://ec.europa.eu/health/ern. Open access funding provided by University of Innsbruck and Medical University of Innsbruck.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

The Core Writing Group, led by CC and KW and consisting of further six members (LGR, MS(Leiden), RG, CPK, EA, LB), defined the scope of the guidelines by formulating PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) questions, developed the recommendations based on the literature review and revised them according to the Delphi survey results. Together, they drafted the subsections of the guideline full text underlying this manuscript and the manuscript. The Guideline Group consisting of eleven members (FA, AAA, KB, BB, BC, VDr, YD, MCJJ, MvK, CRP, MS(Paris) approved and commented the recommendations, the guideline full text and the manuscript. All members of the Core Writing Group and the Guideline Group as well as 53 external experts listed in the acknowledgements participated in the modified Delphi survey.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All members of the ERN GENTURIS CMMRD Guideline Group, including the Core Working Group, have provided disclosure statements on all relationships that they have that might be perceived to be a potential conflict of interest. Amedeo Azizi reports receipt of honoraria or consultation fees from Alexion, AstraZeneca and Novartis. Kevin Beccaria reports previous employment with Carthera SAS. Laurence Brugières reports receipts of honoraria or consultation fees from ESAI and TAKEDA. Chrystelle Colas reports receipt of honoraria or consultation fees from AstraZeneca. Volodia Dangouloff-Ros reports receipt of grants/research support from GE Healthcare. Richard Gallon reports receipt of grants/research support from Cancer Research UK Catalyst and UK National Health Service. Christian Kratz reports support from BMBF ADDRess (01GM1909A) and Deutsche Kinderkrebsstiftung (DKS2021.25). Magali Svrcek reports receipt of grants/research support from Bayer and Roche, and receipt of honoraria or consultation fees from Astellas, MSD and Sanofi. All participants of the ERN GENTURIS CMMRD Delphi survey have provided disclosure statements on all relationships that they have that might be perceived to be a potential source of a competing interests. Andishe Attarbaschi reports receipt of honoraria or consultation fees from Amgen, Novartis, Jazz, Gilead and MSD. Patrick Benusiglio reports receipt of honoraria or consultation fees from AstraZeneca, BMS and MSD. Christof Kramm reports receipt of grants/research support from Deutsche Kinderkrebsstiftung (non-commercial), research collaboration with Bayer to develop NTRK-inhibitors, being a member of the advisory board for Boehringer Ingelheim, and participation in Blueprint Medicines ROVER trial NCT04773782. Eric Legius reports receipt of honoraria or consultation fees from Alexion and AstraZeneca. Rianne Oostenbrink reports receipt of grants/research support from EU Patient-centric clinical trial platform (EU-PEARL), which includes support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, EFPIA, Children’s Tumor Foundation, Global Alliance for TB Drug Development non-profit organization and Springworks Therapeutics Inc., receipt of honoraria or consultation fees from AstraZeneca, and participation in a speaker’s bureau sponsored by Alexion. Enrico Opocher reports receipt of honoraria or consultation fees from Alexion (RareDisease). Markus G. Seidel reports receipt of grants/research support from Takeda, Amgen and Novartis, and receipt of honoraria or consultation fees from Jazz, Amgen and Novartis.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Colas, C., Guerrini-Rousseau, L., Suerink, M. et al. ERN GENTURIS guidelines on constitutional mismatch repair deficiency diagnosis, genetic counselling, surveillance, quality of life, and clinical management. Eur J Hum Genet 32, 1526–1541 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-024-01708-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-024-01708-6

This article is cited by

-

ERN GENTURIS guideline on counselling on reproductive options for individuals with a cancer predisposition syndrome (including genturis)

European Journal of Human Genetics (2026)

-

Case report: a rare case of hereditary colorectal cancer and brain tumor with café au lait spots in a child: constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD) syndrome

Egyptian Pediatric Association Gazette (2025)

-

Clinical and genomic features of Lynch syndrome differ by tumor site and disease spectrum

Nature Communications (2025)

-

The European Reference Network on Genetic Tumour Risk Syndromes (ERN GENTURIS): benefits for patients, families, and health care providers

Familial Cancer (2025)

-

Significant progress in hereditary gastrointestinal cancer research presented at the meeting of the International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumors (InSiGHT) 10th meeting of InSiGHT, June 19th -22nd, 2024, Barcelona, Spain

Familial Cancer (2025)