Abstract

Xia-Gibbs syndrome (XGS) is a rare neurodevelopmental disorder with considerable clinical heterogeneity. To further characterize the syndrome’s heterogeneity, we applied latent class analysis (LCA) on reported cases to identify phenotypic subtypes. By searching PubMed, Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang databases from inception to February 2024, we enrolled 97 cases with nonsense, frameshift or missense variants in the AHDC1 gene. LCA was based on the following 6 phenotypes with moderate occurrence and low missingness: ataxia, seizure, autism, sleep apnea, short stature and scoliosis. After excluding cases with missing data on all LCA variables or with unmatched phenotype-genotype information, a total of 85 cases were selected for LCA. Models with 1–5 classes were compared based on Akaike Information Criterion, Bayesian Information Criterion, Sample-Size Adjusted BIC and entropy. We used multinomial logistic regression (MLR) analyses to investigate the phenotype-genotype association and potential predictors for class membership. LCA revealed 3 distinct classes labeled as Ataxia subtype (n = 11 [12.9%]), Sleep apnea & short stature subtype (n = 23 [27.1%]) and Neuropsychological subtype (n = 51 [60.0%]). The commonest Neuropsychological subtype was characterized by high estimated probabilities of seizure, ataxia and autism. By adjusting for sex, age and variant type, MLR showed no significant association between phenotypic subtype and variant position. Age and variant type were identified as predictors of class membership. The findings of this review offer novel insights for different presentations of XGS. It is possible to deliver targeted monitoring and treatment for each subtype in the early stage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Xia-Gibbs syndrome (XGS, OMIM #615829) is a rare neurodevelopmental disorder caused by de novo autosomal dominant nonsense and frameshift variants in the AT-Hook DNA-Binding Motif-Containing 1 (AHDC1) gene, most of which lead to truncated protein synthesis [1, 2]. Recently, de novo missense variants in AHDC1 have also been proposed to diagnose XGS [3, 4]. Located within the cytogenetic band 1p36.11, AHDC1 contains one exon encoding the protein Gibbin, which plays a role in transcription, epigenetic regulation, epithelial morphogenesis and axonogenesis [5, 6]. Variable expression patterns of Gibbin have been found in the nucleoli, nucleoplasm and the whole nucleus across all tissues, but the protein is in particular highly expressed in the brain [7, 8]. The variants in AHDC1 are postulated to alter its interaction with other proteins important for brain development, thus explaining the neurodevelopmental phenotype [9]. To date, more than 390 persons with XGS are known worldwide [10]. The disease is usually childhood-onset and has overall complex, nonspecific manifestations emerging at different ages. Core phenotypes of XGS include motor delay, speech delay, intellectual disability and hypotonia, while other features such as seizure, short stature and dysmorphisms occur less frequently [2].

The phenotypic spectrum of XGS exhibits great heterogeneity, possibly affected by a combination of demographic factors, genetic background and environmental conditions. It has been noticed that patients with XGS bearing the identical AHDC1 variant do not necessarily have the same clinical presentation [2, 11]. Jiang et al. observed that male patients and patients with truncations near the C-terminus of Gibbin were more likely to be nonverbal [11]. The logistic regression analysis of 34 patients with XGS by Khayat et al. revealed no associations between individual phenotypes and sex, age or ethnicity; while most features could not be predicted by variant position, seizures and scoliosis were more significantly associated with truncations before the midpoint of Gibbin [2]. To better understand the disease mechanism and to promote targeted patient management, the clinical profile of XGS needs to be further characterized.

Therefore, based on reported cases with XGS in the existing literature, the leading aim of this review was to identify phenotypic subtypes of XGS by innovatively applying latent class analysis (LCA), a model-based cluster analysis approach that can be used to reveal and describe underlying patterns within a population [12]. Subsequently, we would examine the phenotype-genotype correlation and investigate predictors of class membership from candidate variables including sex, age, AHDC1 variant type and variant position.

Materials and methods

Search strategy, case enrollment and data extraction

An electronic literature search was carried out in PubMed, Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and Wanfang databases by searching for “AHDC1” or “Xia-Gibbs syndrome” from inception to February 2024. Search results were imported into EndNote library version X7. After removing duplicates, full-text articles were retrieved and assessed. We enrolled cases with XGS with nonsense, frameshift or missense variants in AHDC1; those with microdeletions or microduplications involving AHDC1 were excluded due to the absence of substantial evidence to support their pathogenicity [13]. We also excluded cases if their specific AHDC1 variants were not reported. Finally, a total of 97 distinct cases were enrolled from the literature.

We used a structured form in Microsoft Excel to extract data of the enrolled cases with XGS. For each individual, we recorded sex, age, AHDC1 variant and relevant clinical features. The following phenotypes of XGS were evaluated as yes, no or not available: seizure, scoliosis, sleep apnea, ataxia, speech delay, autism, aggression, anxiety, motor delay, hypotonia, facial dysmorphism, brain dysmorphism, intellectual disability, short stature and hearing deficit. A full list of case information is outlined in Table 1.

Variable and case selection for cluster analysis

Desirable phenotypes for the cluster analysis would be those characterized by moderate occurrence and low missingness. We defined the occurrence rate as the proportion of cases exhibiting a given phenotype relative to the total number of cases in which that phenotype was reported and the missingness rate as the proportion of cases in which a given phenotype was missing relative to the total pool of 97 cases. For each phenotype under consideration, these two metrics were calculated among the 97 cases (Supplementary Table S1) and visualized using a scatter plot (Supplementary Fig. S1), which showed that ataxia, seizure, autism, sleep apnea, short stature and scoliosis were suitable variables to be included in the analysis.

We excluded cases if none of the 6 phenotypes were reported; we also removed several cases presented in conference abstracts due to the inability to accurately match genotype to phenotype data. A total of 85 cases were eventually selected for the subsequent analysis. Their missingness of the 6 phenotypes was reported as follows: ataxia(25/85, 29.4%), seizure (27/85, 31.8%), autism(18/85, 21.2%), sleep apnea(19/85, 22.4%), short stature(18/85, 21.2%) and scoliosis(25/85, 29.4%).

Statistical analysis

LCA was applied to identify mutually exclusive XGS phenotypic subtypes based on the aforementioned 6 phenotypes, which were all coded as binary variables. Missing data were handled by Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation, a robust method using all available data to estimate parameters without the need for imputation [14]. We performed LCA with 1–5 classes and assessed model fit using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Sample-Size Adjusted BIC (saBIC) and entropy. While lower information criteria (IC) values are favored, higher entropy, taking value from 0 to 1, denotes better class separation.

After determining the optimal number of classes, individuals were assigned to a class based on their highest posterior probability. Characteristics of the identified subtypes were reported as mean ± SD for normally distributed continuous variables, medians (interquartile ranges) for non-normally distributed continuous variables and numbers (percentages) for categorical variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA), Kruskal-Wallis test, Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare characteristics across subtypes. For significant comparisons, post-hoc tests with Holm correction were applied to examine pair-wise differences.

Variants were classified as upstream of AT hook domain 1, between AT hook domain 1–2, between AT hook domain 2-3 and downstream of AT hook domain 3. We performed multinomial logistic regression (MLR) analysis to calculate the association between phenotypic subtype and variant position using sex, age and variant type as covariates. We then developed a series of MLR models based on candidate variables including sex, age, variant type and variant position to investigate predicting factors of class membership. AIC and BIC were used to compare models with different covariates.

LCA, statistical tests and MLR were carried out in R software version 4.2.3 and StataMP 18. A two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was taken as statistical significance.

Results

Identification of XGS phenotypic subtypes

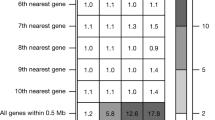

Fit indices for latent class models with 1–5 classes are shown in Supplementary Table S2. By holistically evaluating IC values and entropy, a 3-class model turned out to be the best fit. The estimated probability of the 6 phenotypes for each class is presented in Supplementary Table S3 and visualized comparatively in Fig. 1. The identified classes were labeled as Ataxia subtype, Sleep apnea & short stature subtype and Neuropsychological subtype. The Ataxia subtype was characterized by a relatively high probability of ataxia (0.56) compared to the others (0.00 ≤ probability ≤ 0.15). The Sleep apnea & short stature subtype was characterized by relatively high probabilities of sleep apnea (0.67) and short stature (1.00) compared to the others (0.00 ≤ probability ≤ 0.38). The Neuropsychological subtype was characterized by relatively high probabilities of seizure (1.00), ataxia (0.70) and autism (0.65) compared to the others (0.27 ≤ probability ≤ 0.50). Overall, 12.9% (n = 11) of individuals were classified into the Ataxia subtype, 27.1% (n = 23) into the Sleep apnea & short stature subtype and 60.0% (n = 51) into the Neuropsychological subtype. The missingness of the 6 phenotypes for the identified clusters is presented in Supplementary Table S4.

Characteristics of the identified subtypes

Characteristics of the total cohort and the identified subtypes are summarized in Table 2. Observed differences across the 3 subtypes were noted for the following variables: age (P = 0.04), seizure (P < 0.001), scoliosis (P < 0.01), autism (P < 0.01), ataxia (P = 0.03), sleep apnea (P < 0.001) and short stature (P < 0.001). Post-hoc tests with Holm correction were applied to examine pairwise differences, which are indicated in Table 2 with different superscripts.

To investigate the relationship between age and phenotype, the occurrence of the 6 phenotypes was calculated for the following age groups: 0–6 years (preschool), 6–12 years (school-age), 12–18 years (adolescence) and above 18 years (adulthood). Post-hoc Fisher’s exact test showed that only autism had significantly different occurrence across age (P = 0.05) (Supplementary Table S5).

Association between phenotype and genotype

Distribution of variants along Gibbin by phenotypic subtype and variant type is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. In Table 3, the phenotype-genotype association was further evaluated via MLR by controlling for sex, age and variant type. The Neuropsychological subtype was treated as the reference category as most individuals belonged to this class. Neither the Ataxia subtype nor the Sleep apnea & short stature subtype exhibited significant difference in variant position compared to the Neuropsychological subtype. The subgroup analysis by variant type was not performed due to the limited number of cases.

Predictors of class membership

While the MLR model with age and variant type had the lowest AIC, the one with age alone had the lowest BIC (Supplementary Table S4). Based on theoretical considerations and expert opinions, the former model was preferred. The results are shown in Table 4. Compared to the Neuropsychological subtype, the Ataxia subtype was younger (RRR = 0.99; 95% CI [0.98, 1.00]; P = 0.04) and was more likely to have nonsense variants relative to frameshift variants (RRR = 12.03; 95% CI [2.22, 65.23]; P < 0.01). Likewise, the Sleep apnea & short stature subtype was younger (RRR = 0.99; 95% CI [0.98, 1.00]; P = 0.01) and was more likely to have nonsense variants relative to frameshift variants (RRR = 5.51; 95% CI [1.42, 21.47]; P = 0.01). Figure 2 shows the estimated predicted probability of class membership from 0 to 60 years by variant type.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study using LCA to identify phenotypic subtypes of XGS based on reported cases in the existing literature. Specifically, we identified 3 distinct classes: the Ataxia subtype, the Sleep apnea & short stature subtype and the Neuropsychological subtype. After adjusting for potential confounders, no significant association was observed between phenotypic subtype and AHDC1 variant position. Age and variant type were potential predictors of class membership.

Consistent with prior research, motor delay, speech delay, intellectual disability and hypotonia are core phenotypes of XGS [2]. The LCA based on 6 phenotypes with greater variability provides novel insights into the syndrome’s heterogeneity. Patients with XGS were divided into 3 classes, each with distinct clinical features. Firstly, the Ataxia subtype was characterized by a relatively high probability of ataxia. Since ataxia is a broad term for motor incoordination, this symptom needs to be carefully followed over a long period to distinguish it from a developmental coordination disorder [15] or a cardinal feature of clumsiness among patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder [16]. An association between ataxia and posterior cranial fossa abnormalities has been observed in patients with XGS, suggesting potential brain-behavior relationships [17]. Secondly, the Sleep apnea & short stature subtype was characterized by relatively high probabilities of sleep apnea and short stature. Untreated obstructive sleep apnea can impair growth via increased energy expenditure for breathing during the night and disrupted nocturnal growth hormone (GH) secretion [18]. However, several patients with XGS presented with short stature without concurrent sleep apnea [2, 3, 11, 19,20,21]. This observation suggests that additional mechanisms may contribute to short stature, such as partial GH deficiency reported in 3 patients [17, 20]. Thirdly, the Neuropsychological subtype was the most prevalent class, characterized by relatively high probabilities of seizure, ataxia and autism. The frequent co-occurrence of seizure and autism is well-documented and is proposed as the result of shared divergent neurodevelopmental pathways [22]. Moreover, the mechanisms that lead to seizure may adversely affect social functioning [23].

Through cluster analysis, our review allows for a more nuanced categorization of XGS clinical presentations than previously available. Understanding the heterogeneity of this disorder is crucial for more tailored clinical management strategies. For each subtype, it is possible to implement targeted monitoring and treatment based on the estimated probability for the 6 phenotypes. Specifically, individuals in the Ataxia subtype may benefit from regular follow-ups with neurologists for assessing movement disorders [24]. Rehabilitation therapies can improve patient quality of life and safety. There are also medications that stop or slow symptom progression, but the underlying mechanisms among patients with XGS remain to be elucidated for choosing targeted therapies [25]. Individuals in the Sleep apnea & short stature subtype may benefit from regular follow-ups with otolaryngologists/sleep medicine specialists and endocrinologists for assessing sleep disturbance and retarded growth [24]. Sleep apnea can be treated with behavioral interventions, medical devices or surgical procedures [26]. For short stature, it is vital to screen for the underlying causes and initiate targeted therapies. Growth hormone deficiency, for instance, has been detected in 3 cases with XGS exhibiting good response to growth hormone replacement therapy [17, 20]. Individuals in the Neuropsychological subtype may benefit from regular follow-ups with neurologists and psychologists for assessing seizure, movement disorders and behavioral concerns so that proper.medications, rehabilitation therapies, behavioral therapies and psychiatric consultations can be delivered in time. It is also recommended to educate parents/caregivers about common seizure presentations [24].

The phenotype-genotype association has been elusive in XGS. Jiang et al. observed that patients with truncating variants closer to the C-terminal were more likely to be nonverbal and autistic [11]. The logistic regression analysis by Khayat et al. revealed no associations for most XGS features except seizure and scoliosis, which were associated with truncating variants mapping to the N-terminal to mid-protein positions [2]. These results do not align with our review, and such discrepancies may arise from different analytical perspectives. Unlike previous studies, our review does not focus on individual XGS phenotypes. Nonetheless, it has been noted that AHDC1 variant position may not critically determine clinical presentation as patients carrying the same variant can display distinct phenotypes [11, 19]. To further establish the correlation between phenotype and variant site, a larger cohort of patients is necessary.

The 3 phenotypic subtypes of XGS differed by age and variant type. Younger age and nonsense variant were predictive of the Ataxia subtype and the Sleep apnea & short stature subtype. Our results showed that the association between older age and the Neuropsychological subtype could be explained by the late onset of autism. This pattern may reflect increased social expectations that individuals struggle to meet [17]. The association between phenotype and variant type, on the other hand, has never been reported. Khayat et al. found no associations between individual XGS features and variant type in their study of 34 patients with either frameshift or nonsense variants [2]. Although both frameshift and nonsense variants are expected to result in protein truncation, the difference in class probabilities may stem from other uncontrolled factors such as variant position, sex and ethnicity in the “optimal fit” model. Identifying predictors of XGS subtypes will empower clinicians to anticipate disease progression even before symptoms manifest, allowing for the implementation of targeted interventions in advance.

The limited number of cases has been the major obstacle for research on rare diseases. Thus, a big strength of our review is the systematic search of documented cases with XGS. While this approach alleviates the problem of sample size, inevitable limitations such as data incompleteness have to be acknowledged. To validate the present results, we recommend future research recruiting larger cohorts of patients with XGS through international collaboration and performing standardized, comprehensive data collection (including demographic information, genetic testing and phenotypic assessment). It will be possible to incorporate even more phenotypes into LCA. Prospective studies may also be considered to assess clinical outcomes among different subtypes.

In conclusion, this review validated core phenotypes of XGS based on previously reported cases. The syndrome’s heterogeneity was further elucidated through a novel application of LCA on 6 less frequently encountered phenotypes. The cluster analysis uncovered 3 phenotypic subtypes: the Ataxia subtype, the Sleep apnea & short stature subtype and the Neuropsychological subtype. The commonest class was the Neuropsychological subtype, characterized by high estimated probabilities of seizure, ataxia and autism. While no association between phenotypic subtype and AHDC1 variant position was detected, age and variant type were potential predictors of class membership. These findings are significant, since they not only depict clinical features of XGS but also promote personalized patient care in the early stage.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and its online supplementary material.

Change history

26 February 2025

The original online version of this article was revised: In this article the second affiliation ‘Key Laboratory of Endocrinology of National Health Commission, Department of Endocrinology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, 100730, Beijing, China’ for Nan Jiang was missing. Furthermore, the layout of Table 1 was incorrect and has been corrected.

03 April 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-025-01825-w

References

Xia F, Bainbridge MN, Tan TY, Wangler MF, Scheuerle AE, Zackai EH, et al. De novo truncating mutations in AHDC1 in individuals with syndromic expressive language delay, hypotonia, and sleep apnea. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:784–9.

Khayat MM, Li H, Chander V, Hu J, Hansen AW, Li S, et al. Phenotypic and protein localization heterogeneity associated with AHDC1 pathogenic protein-truncating alleles in Xia-Gibbs syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2021;42:577–91.

Khayat MM, Hu J, Jiang Y, Li H, Chander V, Dawood M, et al. AHDC1 missense mutations in Xia-Gibbs syndrome. HGG Adv. 2021;2:100049.

Gumus E. Extending the phenotype of Xia-Gibbs syndrome in a two-year-old patient with craniosynostosis with a novel de novo AHDC1 missense mutation. Eur J Med Genet. 2020;63:103637.

Collier A, Liu A, Torkelson J, Pattison J, Gaddam S, Zhen H, et al. Gibbin mesodermal regulation patterns epithelial development. Nature 2022;606:188–96.

Quintero-Rivera F, Xi QJ, Keppler-Noreuil KM, Lee JH, Higgins AW, Anchan RM, et al. MATR3 disruption in human and mouse associated with bicuspid aortic valve, aortic coarctation and patent ductus arteriosus. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:2375–89.

Thul PJ, Åkesson L, Wiking M, Mahdessian D, Geladaki A, Ait Blal H, et al. A subcellular map of the human proteome. Science 2017;356:eaal3321.

Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347:1260419.

Yang H, Douglas G, Monaghan KG, Retterer K, Cho MT, Escobar LF, et al. De novo truncating variants in the AHDC1 gene encoding the AT-hook DNA-binding motif-containing protein 1 are associated with intellectual disability and developmental delay. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2015;1:a000562.

Xia-Gibbs Syndrome. Xia-Gibbs Society. 2024. Available from: https://xia-gibbs.org/xia-gibbs-syndrome/.

Jiang Y, Wangler MF, McGuire AL, Lupski JR, Posey JE, Khayat MM, et al. The phenotypic spectrum of Xia-Gibbs syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2018;176:1315–26.

Stahl D, Sallis H. Model-based cluster analysis. WIREs Computational Stat. 2012;4:341–58.

Chander V, Mahmoud M, Hu J, Dardas Z, Grochowski CM, Dawood M, et al. Long read sequencing and expression studies of AHDC1 deletions in Xia-Gibbs syndrome reveal a novel genetic regulatory mechanism. Hum Mutat. 2022;43:2033–53.

Van Lissa CJ, Garnier-Villarreal M, Anadria D. Recommended Practices in Latent Class Analysis Using the Open-Source R-Package tidySEM. Struct Equ Modeling: A Multidiscip J. 2024;31:526–34.

Baxter P. Distinguishing ataxia from developmental coordination disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62:11.

Fournier KA, Hass CJ, Naik SK, Lodha N, Cauraugh JH. Motor coordination in autism spectrum disorders: a synthesis and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:1227–40.

Della Vecchia S, Milone R, Cagiano R, Calderoni S, Santocchi E, Pasquariello R, et al. Focusing on Autism Spectrum Disorder in Xia–Gibbs Syndrome: Description of a Female with High Functioning Autism and Literature Review. Child. 2021;8:450.

Yang S, Mathijssen IMJ, Joosten KFM. The impact of obstructive sleep apnea on growth in patients with syndromic and complex craniosynostosis: a retrospective study. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181:4191–7.

Faergeman SL, Bojesen AB, Rasmussen M, Becher N, Andreasen L, Andersen BN, et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity and mosaicism in Xia-Gibbs syndrome: Five Danish patients with novel variants in AHDC1. Eur J Med Genet. 2021;64:104280.

Cheng X, Tang F, Hu X, Li H, Li M, Fu Y, et al. Two Chinese Xia-Gibbs syndrome patients with partial growth hormone deficiency. Mol Genet Genom Med. 2019;7:e00596.

Murdock DR, Jiang Y, Wangler M, Khayat MM, Sabo A, Juusola J, et al. Xia-Gibbs syndrome in adulthood: a case report with insight into the natural history of the condition. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2019;5:a003608.

Mendez MA, Canitano R, Oakley B, San José-Cáceres A, Tinelli M, Knapp M, et al. Autism with co-occurring epilepsy care pathway in Europe. Eur Psychiatry. 2023;66:e61.

Tuchman R. What is the Relationship Between Autism Spectrum Disorders and Epilepsy? Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2017;24:292–300.

Chander V, Wangler M, Gibbs R, Murdock D. National Library of Medicine. University of Washington, Seattle; 2021. GeneReviews. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK575793/table/xia-gibbs.T.treatment_of_manifestations/.

Perlman SL. Update on the Treatment of Ataxia: Medication and Emerging Therapies. Neurotherapeutics 2020;17:1660–4.

Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM. Diagnosis and Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Review. JAMA 2020;323:1389–400.

Baga M, Ivanovski I, Contrò G, Caraffi SG, Spagnoli C, Cesaroni CA, et al. Novel Insights from Clinical Practice: Xia-Gibbs Syndrome with Pes Cavus, Conjunctival Melanosis, and Eye Asymmetry due to a de novo AHDC1 Gene Variant - A Case Report and a Brief Review of the Literature. Mol Syndromol. 2024;15:63–70. https://doi.org/10.1159/000530410.

Yin T, Wu B, Peng T, Liao Y, Jiao S, Wang H. Generation of a human induced pluripotent stem cell line (FDCHi010-A) from a patient with Xia-Gibbs syndrome carrying AHDC1 mutation (c.2062C>T). Stem Cell Res. 2023;69:103118 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scr.2023.103118.

Lin SZ, Xie HY, Qu YL, Gao W, Wang WQ, Li JY, et al. Novel frameshift mutation in the AHDC1 gene in a Chinese global developmental delay patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:7517–22. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i21.7517.

Teresa Serrano Antón A, José Sánchez Soler M, Ballesta Martínez M, López González V, Rodríguez Peña L, Guillén Navarro E. Refining the phenotype and expanding the genotype of Xia-Gibbs Syndrome (OMIM #615829). Eur J Hum Genet. 2022;30:88–608.

Kutkowska-Kazmierczak A, Wlasienko P, Boczar M, Malinowska O, Gambin T, Kruk M, et al. Xia-Gibbs syndrome - variable clinical manifestation of three cases from a single genetic department. Eur Soc Hum Genet. 2022;30:88–608.

Starosta R, Leestma K, Slaugh R, Luque JLGD. eP254: Novel variant in AHDC1 leading to Xia-Gibbs syndrome: Expansion of the phenotype. Genet Med. 2022;24:S161 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2022.01.289.

Romano F, Falco M, Cappuccio G, Brunetti-Pierri N, Lonardo F, Torella A, et al. Genotype-phenotype spectrum and correlations in Xia-Gibbs syndrome: Report of five novel cases and literature review. Birth Defects Res. 2022;114:759–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdr2.2058.

Salvati A, Biagioni T, Ferrari AR, Lopergolo D, Brovedani P, Bartolini E. Different epilepsy course of a novel AHDC1 mutation in a female monozygotic twin pair. Seizure 2022;99:127–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2022.05.020.

Danda S, Datar C, Kher A, Deshpande T, Thomas MM, Oommen SP. First reported cases with Xia-Gibbs syndrome from India harboring novel variants in AHDC1. Am J Med Genet A. 2022;188:2501–04. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.62844.

Khayat MM, Hu J, Jiang Y, Li H, Chander V, Dawood M, et al. AHDC1 missense mutations in Xia-Gibbs syndrome. HGG Adv. 2021;2:100049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xhgg.2021.100049.

Faergeman SL, Bojesen AB, Rasmussen M, Becher N, Andreasen L, Andersen BN, et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity and mosaicism in Xia-Gibbs syndrome: Five Danish patients with novel variants in AHDC1. Eur J Med Genet. 2021;64:104280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmg.2021.104280.

Della Vecchia S, Milone R, Cagiano R, Calderoni S, Santocchi E, Pasquariello R, et al. Focusing on Autism Spectrum Disorder in Xia–Gibbs Syndrome: Description of a Female with High Functioning Autism and Literature Review. Child. 2021;8:450. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060450.

Khayat MM, Li H, Chander V, Hu J, Hansen AW, Li S, et al. Phenotypic and protein localization heterogeneity associated with AHDC1 pathogenic protein-truncating alleles in Xia-Gibbs syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2021;42:577–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.24190.

Mubungu G, Makay P, Boujemla B, Yanda S, Posey JE, Lupski JR, et al. Clinical presentation and evolution of Xia-Gibbs syndrome due to p.Gly375ArgfsTer3 variant in a patient from DR Congo (Central Africa). Am J Med Genet A. 2021;185:990–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.62049.

Cardoso-Dos-Santos AC, Oliveira Silva T, Silveira Faccini A, Woycinck Kowalski T, Bertoli-Avella A, Morales Saute JA, et al. Novel AHDC1 Gene Mutation in a Brazilian Individual: Implications of Xia-Gibbs Syndrome. Mol Syndromol. 2020;11:24–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000505843.

He P, Yang Y, Zhen L, Li DZ. Recurrent hypoplasia of corpus callosum as a prenatal phenotype of Xia-Gibbs syndrome caused by maternal germline mosaicism of an AHDC1 variant. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;244:208–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.11.031.

Gumus E. Extending the phenotype of Xia-Gibbs syndrome in a two-year-old patient with craniosynostosis with a novel de novo AHDC1 missense mutation. Eur J Med Genet. 2020;63:103637 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmg.2019.03.001.

Díaz-Ordoñez L, Ramirez-Montaño D, Candelo E, Cruz S, Pachajoa H. Syndromic Intellectual Disability Caused by a Novel Truncating Variant in AHDC1: A Case Report. Iran J Med Sci. 2019;44:257–61.

Cheng X, Tang F, Hu X, Li H, Li M, Fu Y, et al. Two Chinese Xia-Gibbs syndrome patients with partial growth hormone deficiency. Mol Genet Genom Med. 2019;7:e00596. https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.596.

Murdock DR, Jiang Y, Wangler M, Khayat MM, Sabo A, Juusola J, et al. Xia-Gibbs syndrome in adulthood: a case report with insight into the natural history of the condition. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2019;5:a003608. https://doi.org/10.1101/mcs.a003608.

Tonne E, Baero H, Prescott T, Tveten K, Holla OL, Sunde LH, et al. Xia-Gibbs syndrome presenting with craniosynostosis, tethered cord and Chiari I malformation. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;27:870–1041.

Ritter AL, McDougall C, Skraban C, Medne L, Bedoukian EC, Asher SB, et al. Variable Clinical Manifestations of Xia-Gibbs syndrome: Findings of Consecutively Identified Cases at a Single Children’s Hospital. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176:1890–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.40380.

Jiang Y, Wangler MF, McGuire AL, Lupski JR, Posey JE, Khayat MM, et al. The phenotypic spectrum of Xia-Gibbs syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176:1315–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.38699.

García-Acero M, Acosta J. Whole-Exome Sequencing Identifies a de novo AHDC1 Mutation in a Colombian Patient with Xia-Gibbs Syndrome. Mol Syndromol. 2017;8:308–12. https://doi.org/10.1159/000479357.

Yang H, Douglas G, Monaghan KG, Retterer K, Cho MT, Escobar LF, et al. De novo truncating variants in the AHDC1 gene encoding the AT-hook DNA-binding motif-containing protein 1 are associated with intellectual disability and developmental delay. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2015;1:a000562. https://doi.org/10.1101/mcs.a000562.

Xia F, Bainbridge MN, Tan TY, Wangler MF, Scheuerle AE, Zackai EH, et al. De novo truncating mutations in AHDC1 in individuals with syndromic expressive language delay, hypotonia, and sleep apnea. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:784–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.04.006.

Zhang M, Li T, Niu G, Xie J, Xia B, Li L. One case of Xia-Gibbs syndrome caused by mutation of AHDC1 gene. Chin Med Case Repository. 2023;5:e02574. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cmcr.2023.e02574.

Meng Y, Zhang W, Wang S. A case report of WANG Su-mei: Chinese herbal medicine Fugui Yizhi Decoction in the treatment of Xia-Gibbs syndrome. Beijing J Traditional Chin Med. 2023;42. https://doi.org/10.16025/j.1674-1307.2023.12.030.

Huang S, Wu P. A case report of Xia-Gibbs Syndrome. Int J Clin Res. 2022;6:1–3. https://doi.org/10.12208/j.ijcr.20220088.

Fan L, Li Y, Luo H, Shen Y, Yuan M, Yang Z, et al. Analysis of a case with Xia-Gibbs syndrome due to variant of AHDC1 gene. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2022;39:397–400. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn511374-20210807-00656.

Qin Y, Gan J, Cai X. Xia-Gibbs Syndrome Caused by AHDCl Gene Mutation: a case Reportand Literature Review. Reflexol Rehabilit Med. 2022;3:165–8.

Su H. Clinical and genetic analysis of Xia-Gibbs syndrome. Chin Pediatrics Integr Traditional West Med. 2020;12:457–62. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-3865.2020.05.025.

Yang S, Li M, Jia C, Ran Y, Wu X. Xia-Gibbs syndrome in a child caused by a de novo AHDC1 mutation and literature review. J Clin Pediatrics. 2019;37:847–50. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-3606.2019.11.012.

Lu T, Wu B, Wang Y. Xia-Gibbs syndrome in a child caused by novel AHDC1 mutation and literature review. Chin J Evid Based Pediatrics. 2018;13:224–7. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-5501.2018.03.014.

Zhang K, Wang T, Yang Y, Lv Y, Gai Z, Liu Y. Clinical and genetic analysis of a Xia-Gibbs syndrome family. Chin J Neurol. 2018;51:961–5. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1006-7876.2018.12.005.

Funding

This work was supported by the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-A-015 and 2022-PUMCH-B-016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NJ, LYZ, SC and HP conceived and designed this work. NJ and LYZ conducted online searches, article screening and data extraction. NJ, LYZ and ZYZ analyzed the data. NJ and LYZ prepared the original draft. HZD and SC revised the manuscript. HP approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: In this article the second affiliation ‘Key Laboratory of Endocrinology of National Health Commission, Department of Endocrinology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, 100730, Beijing, China’ for Nan Jiang was missing. Furthermore, the layout of Table 1 was incorrect and has been corrected.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, N., Zhang, L., Zheng, Z. et al. Phenotypic subtypes of Xia-Gibbs syndrome: a latent class analysis. Eur J Hum Genet 33, 1558–1566 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-024-01754-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-024-01754-0