Abstract

Implementation of genomics in newborn screening is rapidly becoming a reality through accelerated clinical research and investment in genomic sequencing programs. The perspectives of parents who have experienced genetic screening and technologies can inform effective clinical translation and co-design of a model of care for future programs. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with 23 parents of children diagnosed with genetic conditions. Data were evaluated using inductive content analysis methods. Parents valued expeditious, contemporary and accurate information from specialists to manage uncertainties and aid decision-making upon receiving a genomic diagnosis, alongside coordination and collaboration with local services to provide child and family centred care. Integration of psychosocial support into genomic NBS programs was highlighted as an important strategy to mitigate potential psychological risks of receiving a newborn genomic screening result. Integrating genomic NBS in current health ecosystems requires a model that provides care and support across the healthcare journey for the child and family. Information provision and consent at screening facilitates familial understanding of the implications of genomic screening. Equitable access to post screening care and expertise is essential to optimise health and psychosocial outcomes for the child and family and maintain parental acceptability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Newborn screening (NBS) programs are considered one of the most effective public health initiatives of the modern era, with international screening principles developed to standardise conditions amenable to NBS [1]. With advancements in genomic capabilities, the potential to diagnose more children with rare conditions through the use of genomics in NBS (referred to here as genomic NBS) may soon become a reality with acceleration of clinical research studies and investment in genomic sequencing programs [2,3,4].

However, scientific Boards have urged caution with such implementation [5] due to risks of fragmenting existing NBS programs, potentially eroding high uptake [6], and causing irreversible ethical, legal and social harms to affected newborns and their families. Introducing genomics within a population-based screening program also carries with it the potential to inadvertently widen inequities in healthcare access [6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

In Australia, perceptions of healthcare professionals and the public regarding NBS implementation for specific conditions have provided a hypothetical framework for the risks, benefits and challenges of genomic NBS within the current healthcare system [13,14,15,16]. However, there is a paucity of information describing parents’ lived experience, particularly regarding aspects of consent, disclosure, and psychosocial implications of genomic NBS. With the potential introduction of genomics, it is possible that a myriad of conditions could be identified without recourse to expedient and centralised diagnostic services, expert care or multidisciplinary support. Models of care that ameliorate these risks and align with the values, needs and preferences of consumers have not been hitherto evaluated but are imperative to develop. Strategies to address this data gap include collaboration and co-design with families to ensure that adoption of genomic technologies for healthcare on a population level are fit for purpose, equitable and informed by consumer enriched evidence [17].

The aim of the current study was to explore parents’ understanding, attitudes and priorities regarding genomic NBS in Australia. It was hypothesised that the evidence generated would inform the elements required to optimise acceptability, equity and sustainability of models of care for future genomic NBS in Australian and similar healthcare systems.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

This study used a qualitative pragmatic methodology to evaluate Australian parents’ perspectives on the benefits, risks, ethical, legal and social implications related to genomic NBS. In summary, purposive sampling was used to recruit parents with a range of sociodemographic characteristics. Key informants included parents of children diagnosed with genetic conditions through routine Australian NBS programs (including parents of children with false positive and false negative screening results), or after clinical referral following symptom onset. Recruitment eligibility was condition agnostic, though a range of conditions were sought. Recruitment utilised clinical networks through Sydney Children’s Hospital and parents were invited to participate following completion of their child’s routine clinical appointment. In addition, patient advocacy bulletins were used wherein participants registered expression of interest. We purposively invited parents with experience of screen positive, false negative and false positive NBS results. Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Sydney Children’s Hospital Network Human Research Ethics Committee [2023/ETH02371]. A full methodological protocol was also published previously [18].

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with consenting parents. An interview guide was co-developed by investigators with expertise in rare conditions, qualitative methodologies, ethics, legal and social implications, healthcare policy, genomics and NBS. Discussion topics were iteratively defined during co-development (Supplementary Table 1). As genomic NBS is at pre-implementation stage and not embedded in routine care, participants were educated on the potential of genomic NBS, provided through the study invitation letter. Interviews were conducted by SK, CM or JS, two of whom were present at each interview. Interviews were conducted face-to-face or through videoconferencing, ranged between 45 and 90 min duration, and transcribed using professional transcription services. De-identified transcripts were used for analysis. Parents completed a demographic questionnaire and decision-regret scale to assess their satisfaction with pursuing genetic testing or NBS [19].

Data analysis

Transcripts were managed using NVivo (Version 14) and analysed using inductive content analysis (ICA). Transcripts were first coded into broad categories (CM/SGP) with co-coding undertaken in 25% of transcripts by SK to verify classifications. Major categories were identified and iteratively refined into subcategories. Qualitative rigor was promoted through JS, AT, SK, CM and SGP refining the initial coding frame and discussing categories and sub-categories at multiple points during analysis. Discordance in coding was resolved by consensus. Reflexivity was maintained by the research team discussing and challenging assumptions derived from cultural, personal, and professional backgrounds.

Results

Response rate and participant characteristics

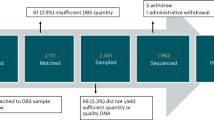

Of 43 individuals who were eligible and approached to participate, 23 consented to participate in the study (response 53%) representing 22 families (including one dyad). Parent and child demographics are summarised in Tables 1 and 2. 22/23 demographic data sheets were returned, with some parents choosing to omit data elements.

The psychosocial impact of receiving a genomic diagnosis

The newborn period was described as a unique and highly vulnerable time (Table 3). Emotions such as anxiety, grief, stress and sadness were exacerbated by receiving a genetic diagnosis and access to psychosocial care was described as necessary for successful implementation of genomic NBS. Despite these feelings, no parents indicated regret at pursuing a genetic diagnosis for their child. Almost half of parents (9/23) reflected on how information gained from a genetic diagnosis empowered their family to prioritise life goals, pursue meaningful activities and create memories, often strengthening the parent-child and sibling relationship (Quote 3.1). In contrast, parents also experienced feelings of distress if a diagnosis was not supported by appropriate education or individualised care, leaving parents unable to use the information proactively; parents felt this could be ameliorated by access to information from their healthcare team, with the role of a genetic counsellor for information provision being highlighted. Feelings of self-blame were identified by some parents as a particular aspect of their child being diagnosed with a potentially inherited genetic condition (Quote 3.2), with one parent reflecting on the potential for an older siblings’ condition to have progressed beyond the optimal therapeutic window due to not having genetic knowledge earlier. A few parents were also hesitant to pursue genetic testing or disclose results beyond the child/parents. Concerns were elevated for some parents when considering the potential for misuse of genomic data, with fears of social and financial discrimination if legal safeguards were not pre-emptively established.

Despite early access to diagnosis and often presymptomatic treatment, over half of parents (16/23) continued to experience pre-emptive grief or anxiety of symptom progression. This had the potential to deny families comfort, causing hypervigilance and in some cases, disrupting the child-parent bond (Quote 3.3). Uncertainty and grief were heavily associated with diagnoses of rare, ultra-rare, under researched, and unpredictable conditions, but did not appear to be associated with the presence or absence of effective treatments. Feelings of loss for the future they envisioned for their child and family caused personal strain for most participants, with one parent describing marital strain due to differences in coping styles with their partner (Quote 3.4). Most parents deliberated the psychosocial impact of diagnostic information, the majority of which felt the benefits outweighed the risks, in particular preventing guilt and self-blame for missing symptoms, and “what if?” questions of a later diagnosis (Quote 3.5).

Increased psychosocial risks of genetic NBS were associated with false positive or negative screening results. Parents emphasised the need for genetic counselling and continued psychosocial intervention to mitigate psychosocial risks and erosion of public confidence in future genomic NBS programs. For one parent whose child received a false negative result, the impression of disease absence caused prolonged information seeking and misdiagnosis, and negatively impacted family time, parental employment, finances and family wellbeing. For the parent whose child received a false positive NBS result, the investigative burden on the child was considerable, and caused significant grief and had the potential to interfere with early child-parent bonding.

Considering the process of consent, disclosure and information provision

Parents felt the psychosocial ramifications of a genetic diagnosis could be supported by tailored and easily accessible information at the time of consenting to NBS, at point of screening and diagnostic disclosure (Table 4). Nearly all parents struggled recalling current NBS consent processes, aside from acceptance of its routine nature, with many unsure what they were consenting to. Half of the parents expressed preference for antenatal education and consent, to allow time for informed decision-making (Quote 4.1).

Whilst most parents advocated for disclosure of all screening results within the newborn stage, some acknowledged a ‘data dump’ could cause overwhelm and worry for conditions not immediately actionable (Quotes 4.2 & 4.3). To counter this, parents suggested using genomic information as a lifetime data repository, to be disclosed across the lifespan, acknowledging this would place responsibility on healthcare services to retrieve and disclose genetic information at appropriate intervals.

Overall genetic literacy varied across parents, with some identifying the need to upskill the general population on the potential risks and benefits of genomic testing before informed consent was achievable (Quote 4.4). Parents found it challenging to distinguish between genetic screening for individual conditions and interrogating the entire genetic code or a panel of genes for selected conditions. Many agreed that genomic NBS panels would need to be flexible to reflect the dynamic therapeutic environment. To enable this, two parents proposed a two-tier consent system with a core panel of conditions amenable to treatment, and an optional panel including conditions without treatment and/or later onset phenotypes. Despite these perspectives and proposed strategies, deliberation and uncertainty were evident in parents’ responses.

Providing equitable access to care, information and support

Parents valued the ability of genomic NBS to provide diagnoses independent of sociodemographic characteristics, familial health literacy, or condition prevalence (Table 5). A strong sense of ethical maleficence was associated with jurisdictional differences in NBS programs (Quote 5.1). Equitable access to timely and appropriate care from screening through to diagnostic confirmation and multidisciplinary management spanning the child’s life was strongly advocated by almost half of those interviewed (9/23), particularly for those in regional and remote areas. Knowledge sharing between specialist hubs and local medical practitioners was deemed necessary to allow care close to home, with acknowledgement that centres of excellence were essential to provide this level of expertise and intervention. Upskilling the regional and rural workforce for genetic counselling, allied health therapies, and psychosocial services, were considered equally important as access to medical treatments (Quote 5.2).

Parents perceived an intrinsic link between their own well-being and ability to support their child’s needs, with tailored support deemed essential to minimising carer burnout (Quote 5.3). Almost half of parents (10/23) described intensive information seeking after receiving screening and diagnostic results (Quote 5.4), and highlighted the lack of available well curated, easily accessible and comprehensive information resources. Parents hypothesised that without access to information and ongoing support as part of genomic NBS pathways, this could lead to substantial psychosocial harms and erosion of public confidence in NBS programs. Of the portion of parents who felt there was a need for information resources, this mostly related to an overview of the affected child and condition specific information (Quote 5.5).

Privacy and data access were also raised as concerns. Access to individuals’ genetic data and data mining from insurance companies were considered as issues requiring careful consideration and regulation. A few parents likened genomic NBS to ‘playing God’ and there were concerns that using this information for future reproductive planning and potentially eliminating certain conditions could reduce social diversity. Finally, when discussing a child’s right to determine how their genetic data is used, many felt it was their parental role to make that decision until their child reached adulthood. However, parents also recognised it as a question they had not previously considered and should interrogate more. To mitigate risks and optimise ethical processes, parents suggested effective and informed messaging, the ability to opt out of genomic NBS whilst still being able to access a routine panel of conditions, transparency regarding storage and access of genetic data, and education amongst the public to increase genetic health literacy (Quote 5.6).

A continuum of benefits of genomic NBS

Parents considered genomic NBS benefits from the perspective of the child, but also often from the perspective of the family as one indistinguishable unit (Table 6). Genetic knowledge, access to treatment and supportive services was seen as a continuum, facilitating engagement in leisure, education and work pursuits meaningful to the family. This knowledge also empowered parents’ decision-making regarding family adjustments to accommodate their child’s current and future needs (Quote 6.1 & 6.2) and for some facilitated early access to disability and advocacy groups, clinical surveillance of the child, treatment and research for siblings, and informing future reproductive decision-making of parents and wider family were identified as broader benefits.

Independent of diagnostic modality, parents conveyed unanimous support for introducing genomics into NBS, with a range of views as to the benefits. Over half of parents (15/23) discussed that they not only valued access to timely treatments that enhanced outcomes for the newborn (e.g. medication and therapy), but also opportunities to access research and non-therapeutic strategies (e.g. lifestyle changes), ability to anticipate the future, and opportunities for risk stratification and clinical surveillance for the child and family (Quote 6.3).

Over half of parents (15/23) emphasised the importance of genomic NBS in facilitating timely diagnoses and treatment, particularly for rare diseases where a lack of information, inequitable access to experts, and heterogeneous symptoms can delay diagnoses. The possibility to deliver targeted allied therapy supports, engage in symptom management and develop individualised plans for proactive care were perceived to minimise acute hospital admissions, reduce co-morbidities, and decrease the probability of end organ damage. In contrast, receiving an early diagnosis through genomic NBS without immediate recourse to treatment for their newborn was considered psychologically challenging and had the potential to change the risk-benefit profile for a few parents (Quote 6.4), however half of parents interviewed perceived that they would rather be equipped with genetic knowledge.

Finally, a quarter of participants (6/23) considered the benefits of genomic NBS to society and the wider health system. This included a preventative approach to care and reduced frequency and length of hospitalisations, which the parents assumed would reduce healthcare costs and could possibly allow resources to be redirected to proactive health services (Quotes 6.5 & 6.6).

Parents perspectives on the attributes of conditions that should be incorporated into genomic NBS

Relative to perceived benefits, parents deliberated around the inclusion criteria for conditions amenable to genomic NBS (Table 7). This was particularly true for conditions without current treatments, later and/or adult-onset phenotypes, or genetic screening results that would predict a risk of a disease in later life. Factors were weighed against one another, including disease severity and risk stratification, the ability to create time for acceptance and adjustment, enacting preventative care, and the ability to advocate for their child’s needs later in life (Quotes 7.1 & 7.2). If an earlier diagnosis would not change disease trajectory, a few parents felt it more useful and psychologically safe to pursue a diagnosis when their child exhibited symptoms. Of these parents, it was agreed that certainty of diagnosis and prognosis was important when considering conditions to be included in genomic NBS (Quote 7.3).

Discussion

The information, support and management needs of parents and children who receive a genetic diagnosis extend beyond the point of screening. Thus, it is important to take a dual view and concurrently understand the lived experiences of parents whose child has received a genetic diagnosis through NBS or diagnostic (genetic) testing, and gain their perspectives on using genomics as an emergent health technology in NBS. Given genomic NBS has not yet been introduced routinely, these experiences provide vital insights into the ethical, social, and equity implications, to ensure health system readiness and provide a road map for the future clinical translation of genomic NBS. Our study has collected these perspectives using a disease agnostic lens and highlighted the importance of involving intended recipients when designing and implementing new models of care for the use of genomics in NBS that are child and family-centred, effective, sustainable and equitable (Fig. 1).

In this study, true informed consent for genomic NBS was deliberated, reflecting the potential for a spectrum of uncertainties and harms related to receiving genetic screen positive results. Innovative approaches can support a shift in clinical practice, with studies in rare diseases demonstrating the value of co-designing practical educational resources and utilising online decision aide to mitigate these risks. In addition, it appeared important to bolster genomics education, across schools, antenatal programs and with family doctors to improve genetic health literacy [20,21,22].

Parents proposed antenatal provision of information, including risks and benefits to facilitate informed consent, whilst also considering the potential for a tiered consent process. The latter strategy reflects global taskforce views that this method of implementing genomic NBS can maintain the effectiveness and societal support of current screening programs [23], allowing families to opt for screening of conditions that require intervention in the newborn period or have current access to timely medical treatments, whilst deferring screening for conditions not meeting current principles for population-wide screening [1, 24].

The co-design of contemporary, well curated and tailored resources can support the needs and preferences of parents. Our study findings identified that an overview of the healthcare journey for the affected child, condition specific information, ongoing counselling and evidence-based multi-disciplinary management are important components of genomic NBS. Information and psychosocial support must also be accessible and inclusive [25].

Parents acknowledged feelings of distress caused by receiving a genetic diagnosis, that in some cases extended beyond the initial juncture of result disclosure. The benefits of screening versus the stress experienced by parents have previously been discussed and evaluated in an American ethnographic study [26]. Psychological care and support that is embedded into future genomic NBS programs appears an effective pathway for ameliorating caregiver stress, empowering parents with knowledge to optimise self-care, and to promote resilience in navigating the often-dynamic healthcare needs of their child across complex healthcare systems [27, 28]. The triad of psychological care and support, information provision and informed consent align with the principles of safety (including acknowledging the experiences and feelings of families), trust through transparent communication and collaboration, informed decision-making and choice, and culturally and linguistically competent care [29], which parents in this study considered as relevant and appropriate aspects to consider in future models of care.

With prior studies recognising the potential for an increasing frequency of a screened population to have a genomic NBS screen positive result [30], successful implementation requires deepening the capacity for ongoing management of identified children, and resolution of false (negative and positive) screening results. Genomic sequencing has the potential to identify conditions of variable or adult-onset, requiring surveillance, a high-monitoring burden for the child, family and healthcare system and creating diagnostic uncertainty. As a solution to this, parents proposed a two-tier testing model of care including a core set of conditions to fit traditional screening principles and an opt-in panel for (early and later/adult-onset) conditions, that would create the individual flexibility of approach preferred by parents [31].

Provision of care by experts was valued by parents in this study, yet critically, there are limitations in the number of clinicians and scientists available to interpret and communicate complex genomic data, perhaps setting an impetus to train and upskill the current and future health workforce [32]. Parents reinforced that knowledge sharing, conjoint clinical reviews and collaboration between specialist centres and local services could help mitigate sociodemographic inequities of genomic NBS and streamline healthcare journeys for the child and family. Taken together, a hub-and-spoke model of care that provides pathways for specialist centres to support local services may be appropriate to optimise health, psychosocial and financial outcomes for children and families, and facilitate care within their own communities [33]. Leveraging telehealth capabilities accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic can also facilitate best practice care by local clinicians.

Parents highlighted the need for a nationally coordinated system of genomic NBS to mitigate geographical inequities arising from differences between health and state jurisdictions. This aligns with recommendations for universal access to genomic technologies as a core principle of public health and justice [23, 34]. Parents’ perspectives mirror emerging national and international recommendations to redefine a treatable condition to one which can minimise symptoms and low value care, prolong life expectancy, and end diagnostic quests [35]. These considerations remain important for decision-makers to achieving high-quality, family-centred care, and maintaining public trust and uptake in newborn screening programs.

The concept and value of genomic data as a lifetime repository was highlighted by Australian parents for the first time in this study. These findings align with public health and policy considerations that have proposed staged disclosure of genetic data when it is clinically relevant and/or at set time points. This includes immediate disclosure for medically treatable conditions in childhood, and later disclosure after reconsenting for adult-onset conditions and those associated with reproductive (carrier) risk [21, 36]. The resources and follow-up required for this process however have not been fully estimated.

Finally, the study highlighted parents’ awareness of data privacy and storage as a risk of genomic NBS. Future genomic NBS programs may require ongoing review as to the legal safeguards for storage, access and linkage of genomic information for clinical, current and future research purposes to maintain parent trust in existing NBS programs and enable successful translation of genomic NBS programs into healthcare systems [37].

Strengths and limitations

Despite the small number of participants, this study is the first to explore parental lived experience of genetic newborn screening or genetic testing for their child within the Australian healthcare system. Recruitment was condition agnostic and included a range of genetic conditions and diagnostic pathways, which limited biases that may arise from specific disorders and provided a range of experiences and learnings. In a field that is fast evolving, qualitative insights lay the foundation for future studies in areas that are priorities for consumers. Parent preferences for antenatal education, integrated psychosocial support and timely access to intervention are important considerations when co-designing future models of care for genomic NBS that are ethical, effective and equitable. Findings will also inform a best-worst scaling choice survey of the Australian public, to evaluate the relative importance of attributes relevant to genomic NBS.

Whilst recruitment aimed for sampling of a diverse population, most respondents were female and educated, and almost all had English as the primary language. This may bias results and limit generalisability of findings to educational, socio-economic and culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, including indigenous communities. Due to the robustness of screening assays, there were few false positive/negative participants which may limit the interpretation for parents who have not had a typical screening journey. Furthermore, due to purposive sampling of participants whose child/ren had a diagnosed genetic condition, their views may differ from parents who have not had these experiences or declined participation in this study, or whose child had genetic variants of unknown significance. Understanding the latter groups’ perspectives are vital for future studies due to the complexities of understanding disease risk, implications for management including surveillance regimens and supporting parents through uncertainty.

Conclusion

The perspectives of parents regarding the adoption of genomic NBS in Australia is a critical first step to inform co-design of a model of care that effectively and efficiently adopts genomics in NBS programs. Informed by the needs of the community, the perspective of parents remains a vital foundation for genomic NBS to be fit for purpose and appropriate, for potential risks to be mitigated and opportunities magnified. Genomic NBS pathways should begin during the antenatal period and connect the child, family, specialists and local healthcare professionals with one another. This is focused on providing tailored support that is responsive to the child’s needs across the lifespan, as well as the rapid acceleration of technology and research that drives treatment, supportive care and best practice standards. Due to finite resources within the health system, considerations such as re-structuring current ways of working or prioritising resource allocation is recommended to ensure the needs identified by parents are included in high quality and sustainable care and support. The perspectives of parents need to be contextualised within a framework where receiving a diagnosis in the newborn period is a significant experience in and of itself, and future research should explore and differentiate aspects that are specific and relevant to the (genomic) technology in question.

Future directions include using study findings to inform attributes of conditions included in genomic NBS, consent and disclosure processes, and research related to psychosocial, ethical and legal implications. Comparing parental experiences of genomic NBS across disorders, with children at different disease stages or developmental ages may also identify significant differences that are pertinent when developing future models of care that align with the needs, preferences and perspectives of consumers.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available to maintain the confidentiality of study participants, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wilson JMG, Jungner G. Principles and practice of screening for disease. Geneva: WHO; 1968. https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/4/07-050112BP.pdf.

Vears DF, Savulescu J, Christodoulou J, Wall M, Newson AJ. Are we ready for whole population genomic sequencing of asymptomatic newborns?. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2023;16:681–91.

Hussain Z. Over £175m investment in genomic research aims to detect more genetic disorders at birth. BMJ. 2022;379:o2996. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o2996.

The International Consortium on Newborn Sequencing. Global Projects. 2024. https://www.iconseq.org/global-projects.

Borghesi A, Mencarelli MA, Memo L, Ferrero GB, Bartuli A, Genuardi M, et al. Intersociety policy statement on the use of whole-exome sequencing in the critically ill newborn infant. Ital J Pediatr. 2017;43:100.

Charli J, Michelle AF, Sarah N, Kaustuv B, Bruce B, Ainsley JN, et al. The Australian landscape of newborn screening in the genomics era. Rare Disease and Orphan. Drugs J. 2023;2:26.

Sobotka SA, Ross LF. Newborn screening for neurodevelopmental disorders may exacerbate health disparities. Pediatrics. 2023;152:e2023061727.

Aiyar L, Channaoui N, Ota Wang V. Introduction: the state of minority and health disparities in research and practice in genetic counseling and genomic medicine. J Genet Couns. 2020;29:142–6.

Van Mil H. Implications of whole genome sequencing for newborn screening: a public dialogue. 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/60e584418fa8f50c79779207/WGS_for_newborn_screening_FINAL_ACCESSIBLE.pdf.

Kinsella S, Hopkins H, Cooper L, Bonham JR. A public dialogue to inform the use of wider genomic testing when used as part of newborn screening to identify cystic fibrosis. Int J Neonatal Screen. 2022;8:32.

Kerruish N. Parents’ experiences 12 years after newborn screening for genetic susceptibility to type 1 diabetes and their attitudes to whole-genome sequencing in newborns. Genet Med. 2016;18:249–58.

Lunke S, Bouffler SE, Downie L, Caruana J, Amor DJ, Archibald A, et al. Prospective cohort study of genomic newborn screening: BabyScreen+ pilot study protocol. BMJ open. 2024;14:e081426.

Cao M, Notini L, Ayres S, Vears DF. Australian healthcare professionals’ perspectives on the ethical and practical issues associated with genomic newborn screening. J Genet Couns. 2023;32:376–86.

Lynch F, Best S, Gaff C, Downie L, Archibald AD, Gyngell C, et al. Australian public perspectives on genomic newborn screening: risks, benefits, and preferences for implementation. Int J neonatal Screen. 2024;10:6.

Kariyawasam DST, D’Silva AM, Vetsch J, Wakefield CE, Wiley V, Farrar MA. We needed this”: perspectives of parents and healthcare professionals involved in a pilot newborn screening program for spinal muscular atrophy. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;33:100742.

Ji C, Kariyawasam DS, Sampaio H, Lorentzos M, Jones KJ, Farrar MA. Newborn screening for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: the perspectives of stakeholders. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2024;45:101049.

Australian Government, Department of Health. The National Health Genomics Policy Framework 2018-2021. ACT: Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council Canberra; 2017.

Kariyawasam DS, Scarfe J, Meagher C, Farrar MA, Bhattacharya K, Carter SM, et al. Integrating ethics and equity with economics and effectiveness for newborn screening in the genomic age: a qualitative study protocol of stakeholder perspectives. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0299336.

Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ, Hack TF, Siminoff L, Gordon E, et al. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Mak. 2003;23:281–92.

Timmins GT, Wynn J, Saami AM, Espinal A, Chung WK. Diverse parental perspectives of the social and educational needs for expanding newborn screening through genomic sequencing. Public Health Genomics. 2022;15:1–8.

Milko LV, Rini C, Lewis MA, Butterfield RM, Lin FC, Paquin RS, et al. Evaluating parents’ decisions about next-generation sequencing for their child in the NC NEXUS (North Carolina Newborn Exome Sequencing for Universal Screening) study: a randomized controlled trial protocol. Trials. 2018;19:344.

DeLuca JM. Public attitudes toward expanded newborn screening. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;38:e19–e23.

Ross LF, Ormond KE. Newborn sequencing: the promise and perils. Annu Rev Genom Hum Genet. 2025;26:401–23.

Australian Government, Department of Health. Newborn Blood Spot Screening- National Policy Framework. 2018. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/10/newborn-bloodspot-screening-national-policy-framework.pdf.

Salunke J, Byfield G, Powell SN, Torres D, Leon-Lozano G, Jackson J, et al. Community collaboration in public health genetic literacy: co-designing educational resources for equitable genomics research and practice. medRxiv 2024. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.05.24.24307892v1

Timmermans S, Buchbinder M. Saving babies? The consequences of newborn genetic screening. University of Chicago Press; 2019.

Gaviglio A, Hamrick KS, Schwoerer JS, Stone L, Justice K, Edick M. Genetic providers’ views on trauma-informed care in genetics clinics. Genet Med Open. 2024;2:101455:P556.

Prevention and Response to Violence Abuse and Neglect Government Relations (PARVAN). 2023. Integrated Trauma Informed Care Framework: My story, my health, my future. NSW Health, St Leonards, NSW; 2023.

Australian Government, Department of Social Services. Factsheet: Trauma-Informed Practice. 2023. Available from: https://www.dss.gov.au/system/files/documents/2024-11/dsi_act_-_fact_sheet_-_trauma-informed_practice.pdf.

Ceyhan-Birsoy O, Murry JB, Machini K, Lebo MS, Yu TW, Fayer S, et al. Interpretation of genomic sequencing results in healthy and ill newborns: results from the BabySeq project. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104:76–93.

Jez S, Martin M, South S, Vanzo R, Rothwell E. Variants of unknown significance on chromosomal microarray analysis: parental perspectives. J Community Genet. 2015;6:343–9.

Dikow N, Ditzen B, Kolker S, Hoffmann GF, Schaaf CP. From newborn screening to genomic medicine: challenges and suggestions on how to incorporate genomic newborn screening in public health programs. Med Genet. 2022;34:13–20.

Rare Disease Awareness, Education, Support and Training (RArEST) Project. National Recommendations for Rare Disease Health Care. 2024. Available from: https://www.rarevoices.org.au/national-recommendations.

Friedman JM, Cornel MC, Goldenberg AJ, Lister KJ, Senecal K, Vears DF, et al. Genomic newborn screening: public health policy considerations and recommendations. BMC Med Genomics. 2017;10:9.

Bombard Y, Miller FA, Hayeems RZ, Avard D, Knoppers BM, Cornel MC, et al. The expansion of newborn screening: is reproductive benefit an appropriate pursuit?. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:666–7.

Schaaf CP, Kolker S, Hoffmann GF. Genomic newborn screening: proposal of a two-stage approach. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2021;44:518–20.

Tarini BA, Goldenberg AJ. Ethical issues with newborn screening in the genomics era. Annu Rev Genom Hum Genet. 2012;13:381–93.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our thanks to Siun Gallagher for providing feedback on the coding frame used in this study. Thank you also to Siun Gallagher and Professor Ainsley Newson for reviewing early iterations of the manuscript and providing annotations. Finally, our gratitude to Danya Vears for her guidance regarding the use of inductive content analysis.

Funding

DSK acknowledges support by the National Health and Medical Research Council under grant number 2026317.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SGP completed data analysis and manuscript preparation; CM completed data collection, data analysis, and manuscript review; JS was involved in study design, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript review; KB was involved in data collection and manuscript review; AT was involved in data collection; JW was involved in study design and manuscript review; SN contributed to study design and manuscript review; MF was involved in study design, data collection, and manuscript review; DK was involved in study design, data collection, data analysis and manuscript review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Sydney Children’s Hospital Network Human Research Ethics Committee [2023/ETH02371]. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paguinto, SG., Meagher, C., Scarfe, J. et al. “The ability to get ahead”: Australian parent perspectives on genomics in newborn screening and considerations for potential models of care. Eur J Hum Genet (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-025-01971-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-025-01971-1