Abstract

Although next-generation sequencing has emerged as a powerful tool for diagnosing rare diseases (RD), many cases of inherited metabolic diseases (IMD) remain unsolved, hindering the diagnosis, clinical and therapeutic management of the patients. The primary aim of this study is to address the most elusive cases by applying long-read sequencing (LRS) targeted to the gene of interest on seven patients (FARS2, GYS2, PEX1, SLC2A1, AGL, ACAT1, and ACADM), identifying six novel pathogenic variants including two intronic variants, a structural variant and three transposable elements (TE) insertions. In addition, we have demonstrated the effect on splicing of an exonic variant previously reported as missense. Functional genetic tests specific for the expected effect of each variant of uncertain significance were designed, such as minigenes analysis or chromatin conformation capture assay. From the TE insertions, two were located in the genomic region of GYS2 or PEX1, causing a reduction in their mRNA expression. The third was located 7.6 kb downstream of SLC2A1; it alters the interaction between the SLC2A1 promoter and its distal regulatory element via the establishment of a loop with the 3’ border of the native topologically associating domain. This study shows that the combination of LRS and functional genetic assays confers a powerful approach for expanding the mutational spectrum of IMD, adding data to improve the diagnosis of this large group of RD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inherited metabolic diseases (IMD) are a diverse group of nearly 2000 disorders that collectively represent somewhat common disorders [1]. Currently, the gold standard for diagnosis involves identifying abnormal levels of biochemical markers in newborn screening or after the first manifestation of the symptoms. This diagnosis should be confirmed by molecular-genetics technologies [2].

The emergence of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become the gold standard for genetic testing. Exome sequencing (ES) is the most commonly used genetic test in the clinical setting; however, it leaves a significant number of cases undiagnosed [3]. Thus, other technologies that target a wider spectrum of genetic variation are needed [3].

The variants that fall in non-coding regions can impact various mechanisms, such as splicing [4] or transcription regulation. In complex eukaryotes, gene expression is regulated by non-coding sequences known as cis-regulatory elements (CRE), including promoters and enhancers [5]. While the basal promoters are located in proximity to the gene’s transcription start site (TSS), enhancers are often found in distant regions, requiring the 3D conformation of chromatin to bring them into physical proximity. Topologically Associating Domains (TADs) delimit, in large part, gene’s regulatory landscapes and are established by the activity of CCCTC binding factor (CTCF) and cohesin [6]. Thus, variants affecting CRE activity or TAD organization may contribute to disease [7].

Short-read genome sequencing (srGS) increases the diagnostic rate compared to exome sequencing, some cases remain incomplete [8]. One of the main drawbacks of srGS is its limited read length [9] that prevents the detection of some structural variants (SV) and tandem repeat expansions (TREs). Long-read sequencing (LRS) enables mapping of repetitive or duplicated regions, detection of TREs and SV at the same time, resolving break-points at nucleotide resolution [10]. Additionally, the sequencing of native molecules eliminates PCR bias, conferring this technology the ability to analyze epigenetic mechanisms [10] and allows phasing of all types of variants detected.

SVs are defined as differences between huge DNA segments, normally bigger than 50 bp, across genomes. They are usually produced by errors during DNA replication or repair. Genomic regions with a high percentage of homology can lead to erroneous recombination events, resulting in different types of SV. Transposable elements (TE) are sequences with a high number of repeats that comprise around two-thirds of the human genome and can serve as homology regions for the generation of SV [11,12,13,14].

Among the different classes of TE, only non-Long-Terminal Repeats retrotransposons, such as Long Interspersed Nuclear Elements (LINEs), specifically L1 subfamily, Alu, and SINE-VNTR-Alu (SVA), maintain the ability to move in the human genome [15, 16]. The insertion of TE fragments in the genome can lead to disease by exon interruption, alteration of splicing, epigenetic changes, deletion production or even by changing the chromatin conformation [11, 12, 16, 17].

New technologies have significantly increased the number of identified variants, which require the determination of their effect. While in silico predictors may help prioritize them, they are not sufficient to establish their pathogenicity. Therefore, functional genetic tests are necessary [18], such as minigenes for splicing variants, reporter assays for changes in promoters or enhancers, chromatin conformation capture techniques to analyze alterations in chromatin 3D interactions, among others [19].

In this work, taking advantage of the metabolic profiling of our participants, we have been able to focus our study on specific loci, which removes a limitation to clinical use of LRS. We have tested the potential use of LRS targeted to specific loci in combination of a comprehensive set of functional and metabolomics assays to reduce the diagnosis gap in IMD.

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants’ fibroblasts (from all cases except for P2, from which a hepatic biopsy was used) were obtained from skin biopsies. Cultures were maintained in Minimal Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% glutamine, 100,000 U/L penicillin and 100 mg/dL streptomycin. Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator held at 5% CO2 and 37 °C.

RNA studies

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 1.5 μg of RNA were used for cDNA retrotranscription using the SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MS, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Fragments of interest were amplified by PCR using FastStart Taq DNA Polymerase (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and specific primers and Sanger sequenced using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Differential gene expression was analyzed by RT-qPCR. This assay was performed starting with 250 ng total RNA that was transcribed to single-stranded cDNA using NZY First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (NZYTech, Lisbon, Portugal) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Specific primers were designed for AGL (HGNC:321) and SLC2A1 (HGNC:11005). GUSB (HGNC:4696) was used as an endogenous control. qPCR experiments were performed in a LightCycler® 480 Instrument (Roche Applied Science) using PerfeCTa SYBR® Green FastMix (Quantabio, Beverly, MA, USA), following the LightCycler® manufacturer’s instructions except for the amplification step which was modified to 10 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 60 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C. Cycle threshold values were obtained and analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Primers used for amplification will be sent upon request.

Long-read sequencing

High-purity DNA was extracted from peripheral blood or from participant-derived fibroblasts using the MagNA Pure Compact System and either the MagNA Pure Compact Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit I-Large Volume or the MagNA Pure Compact Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit I (Roche Applied Science) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

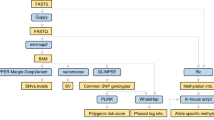

Libraries were prepared with 1d Ligation Library Prep Kit (Oxford Nanopore Technologies [ONT], Oxford, UK) utilizing LSK114 for P5 and P7 and LSK109 for the rest, and were sequenced in a MinION or PromethION P2 device (ONT) using R9.4.1 for P1, P2, P3, P4 and P6 and R10.4.1 for P5 and P7. For sequencing and enrichment of the target region, the adaptive sampling tool [20] was used, implemented in the MinKNOW software (ONT), using a bed file with the genomic coordinates of interest. Bioinformatic analysis of the generated data was performed with a pipeline from Longseq Applications that consisted of: i) base calling using Dorado base caller, which is integrated within the MinKNOW software [21] using FAST basecaller for P1, P2, P3, P4 and P6 and HAC for P5 and P7; ii) alignment to the human reference assembly (GRCh38) using Minimap2 [22]; iii) variants calling with Sniffles2 [23] software for SVs, iv) Clair3 was used for SNV calling and phasing of alignments [24], v) annotation of the variants was done using SnpEff, SnpSift, VEP. For visual inspection and interpretation of long-read alignments, Integrated Genome Viewer (IGV) was used [25]. The data quality was assessed using MinION QC and QualiMap tools. Methylation calls were only obtained for P7.

All variants were named following the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) recommendations and verified using the software VariantValidator [26].

Minigene studies

To examine the splicing pattern in vitro, the pSPL3 vector was used (Exon Trapping System, Gibco, BRL, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The fragment containing ACAT1 (HGNC:93) exon 10 and adjacent intronic regions was isolated from the case and cloned into the pGEMT-Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WA, USA) and the alleles isolated. The insert was excised with EcoRI (Roche Applied Science), purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen), and subsequently cloned into the pSPL3 vector dephosphorylated with Thermosensitive Alkaline Phosphatase (Promega). Ligation was performed using the Rapid DNA Ligation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Restriction enzyme analysis and Sanger sequencing were used to select the clones containing the desired wild-type and mutant alleles. Two µg of the wild-type or mutant minigene were then transfected into the HepG2 cell line using JetPEI transfection reagent (Polyplus-Transfection, Illkirch, France) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were harvested 48 h post-transfection. Transcription profile studies were performed as described in the section RNA studies, and amplification was performed with vector internal primers.

Luciferase reporter assay system

The promoter sequence, including the potential TSS of ACADM, was identified using the Eukaryotic Promoter Database (EPD) (https://epd.epfl.ch//index.php) and the ENCODE Candidate Cis-Regulatory Elements (cCRE) registry on the University of California, Santa Cruz genome browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/).

The selected region was amplified both from healthy control and patient fibroblasts using specific primers carrying the Gateway attB1 and attB2 sites and cloned into the pDONRTM221 vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using Gateway™ BP Clonase™ II (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The obtained vector was transformed in the DH5α strain. The NC_000001.11(NM_000016.5):c.-440T>C variant was both introduced in the control DNA using QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and isolated from the case. Next, the insert was moved to the pIRIGF vector (Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA) by recombination using Gateway™ LR Clonase™ II (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Clones were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

The HepG2 cell line was then transfected with 2 µg of wild-type or mutant constructs using JetPEI transfection reagent (Polyplus-Transfection) following the manufacturer’s indications. Cells were harvested 48 h post-transfection.

Firefly and Renilla reniformis luciferase activities were assessed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) following the manufacturer’s indications, and detected using FLUOstar OPTIMA microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Durham, NC, USA).

Circular chromatin conformation capture

Circular Chromatin Conformation Capture coupled to NGS (4Cseq) experiments were performed and analyzed as in our previous study [27]. Viewpoint-specific primers for the SLC2A1 promoter or CRE region are indicated in Supplemental Information (Table 2)

AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

Grammarly has been used to improve the readability of the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Results

In this study, we included seven participants (P) (Table 1) presenting clinical and/or biochemical suspicion of an IMD. The possible diagnoses were a combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency (MIM#614946), glycogen storage disease (MIM#240600/MIM#232400), peroxisome biogenesis disorder (MIM#214100), glucose transporter 1 deficiency syndrome (GLUT1-DS; MIM#606777), alpha-methylacetoacetic aciduria (MIM#203750), or medium-chain Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MIM#201450). All these diseases are associated with an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, except for GLUT1-DS, which has an autosomal dominant inheritance.

Following the clinical and/or biochemical diagnosis, ES analysis identified a heterozygote pathogenic variant in six participants (five exonic and one intronic), which are associated with an autosomal recessive inheritance, while no pathogenic variants were found in the patient with GLUT1-DS possible diagnosis (Table 2). All variants had been previously described in HGMD (2025 v3), except for ACAT1 NM_000019.4:c.841G>A. Despite this clinical testing, all cases remained unsolved.

Transcriptional studies

In an attempt to identify the cause of the disease in the seven cases, we conducted RNA studies in participant-derived fibroblasts to evaluate the effect of possible variants affecting expression, splicing, or mRNA stability. For P1, the transcriptional profile was previously reported [28], detecting two amplicons: one containing the two single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) detected in ES and a smaller amplicon which exhibited a skipping of exons 3 and 4 and a portion of exon 2 (r.49_904del) of FARS2 (HGNC:21062).

We detected exon 10 skipping in GYS2 (HGNC:4707) (Fig. 1A), and no variants in exon 10 and flanking regions were detected in GYS2 that could explain the skipping detected in P2. Exon 32 skipping in AGL was detected in P5 and was attributed to variant NC_000001.11(NM_000642.3):c.4260-1G>T previously identified by ES (data not shown). Both exons skipping result in out-of-frame transcripts. We also detected two aberrant isoforms of ACADM (HGNC:89) produced by the exonic variant NM_000016.5:c.542A>G previously misclassified as missense. One consists on a shortening of 58 bp of exon 7 (r.542_599del) producing an out-of-frame transcript (Fig. 1C), and the other consists on a 87 bp shortening, from which 58 bp correspond to exon 7 and 29 bp to exon 8 (r.542_628del), resulting in an in-frame deletion (Fig. 1C).

A Sashimi plot obtained for GYS2 in P2. Exon 10 skipping is marked with the black rectangle. B Quantification of the percentage of reads of cDNA of PEX1 and ACAT1 with or without (wt) the exonic variants detected in P3 and P6. C Transcriptional profile of the ACADM gene performed in RNA isolated from control (C) or P7 fibroblasts. Wild-type or aberrant transcripts of ACADM are represented on the right with the exonic variant NM_000016.5:c.542A>G marked in red. Deleted regions are depicted in light gray. All bands have been Sanger sequenced. D Quantification of the percentage of reads obtained after next-generation sequencing of the ACADM cDNA obtained from case P7. The percentage of reads with a normal splicing pattern or mutant with either the 58 bp or the 87 bp deletions are represented.

Allele-specific expression (ASE) was detected in three cases. Thus, the variants NM_000466.3:c.2097dup and NM_000019.4:c.841G>A present in PEX1 (HGNC:8850) and ACAT1, respectively, displayed increased read numbers compared to their wild-type alleles (Fig. 1B), while aberrant ACADM transcripts caused by NM_000016.5:c.542A>G were increased (Fig. 1D). Besides, RT-qPCR quantification confirmed a significant reduction of 96% or 80% of AGL or SLC2A1 mRNA expression in P5 and P4, respectively, when compared to at least three healthy controls (data not shown).

Long-read sequencing

The observed transcriptional defects prompted us to search for non-coding variants by LRS targeted to cover up to 3 Mb of the genes of interest, thus encompassing the targeted locus and its regulatory landscape.

In P1, we detected two reads showing a tandem duplication that includes the complete sequence of exon 5 of FARS2 (Fig. 2A). This duplication was absent in DECIPHER. We designed a specific PCR and confirmed the disease-specific duplication (Fig. 2B, C), determining the variant’s breakpoints: NC_000006.12(NM_006567.5):c.905-5741_1065+1116dup that could not be previously mapped due to low coverage. Since we did not have parental samples available, we could not conduct segregation studies. Also, the low coverage of the LRS experiments did not allow for phasing the SV and the SNV identified in ES. The results suggest a duplication of exon 5 (161 bp) in the cDNA that likely causes a frameshift and ultimately leads to the degradation of the abnormal transcript (Fig. 2A). This additional genomic analysis suggests that the aberrant transcript observed in previous studies [28] is a result of this duplication.

A Read visualization in the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV). The figure shows the pairs of linked reads in green and blue, both covering the duplication of exon 5. The left-lower part of the panel represents the specific PCR and RT-PCR amplification assay to confirm the exon 5 duplication in gDNA and cDNA. The primers used for RT-PCR are indicated in the figure. The upper part depicts the wild-type allele (WT) and the lower part the allele with the structural variant (SV), the duplication is marked in red. The forward (F) and reverse (R) primers used for the amplification are represented as black arrows. The right-lower part of the panel shows the agarose gel results of the specific PCR. B Read visualization in IGV. The figure shows, marked by a red rectangle, the insertion of a fragment of a Long Interspersed Nuclear Element (LINE) in the exon 10 of GYS2. The left-lower part of the panel represents the specific PCR amplification assay to confirm the LINE insertion. F and R primers are marked with black arrows. The right-lower part of the panel shows the agarose gel results. C Read visualization in IGV of the results for P3. The figure shows, marked by a red rectangle, the insertion detected in intron 8 of PEX1. D Read visualization in IGV of the results for P4. The figure shows, marked by a red rectangle, the LINE fragment insertion detected in the 3’ region of SLC2A1. MW molecular weight marker, C control sample, P parental sample, M Maternal sample.

We also identified TE insertions among three different participants. The sequence revealed two LINE1 fragments and one SVA in GYS2, SLC2A1 and PEX1, respectively. In P2, a 1.5 kb fragment of a LINE_L1 (NM_021957.4:c.1300_1301ins[PP887427.1:g.1_1518]) was detected inserted in exon 10 of GYS2 (Fig. 2B). This insertion likely causes the 79 bp skipping of exon 10 (previously observed) and the subsequent degradation of the aberrant mRNA due to the existence of a frameshift. The presence of the insertion was confirmed in the paternal allele by a specific PCR assay (Fig. 2B). Instead, the 2.6 kb SVA insertion of P3 occurred in intron 8 of PEX1 (Fig. 2C). Finally, ONT sequencing of P4 identified a 2.5 kb LINE_L1 insertion 7.6 kb downstream of SLC2A1 in both fibroblast and blood-extracted DNA (Fig. 2D). None of the three insertions has been reported in the control population before.

Regarding SNVs, we detected four novel variants. In P5, we found a novel deep intronic variant NC_000001.11(NM_000642.3):c.3259+927A>G in AGL, in trans with the previously detected variant. According to different in silico predictors, this variant increased the strength of a pre-existing splicing donor. For P6, a novel intronic variant was detected in ACAT1 (NC_000011.10(NM_000019.4):c.941-60T>C) that eliminated a SRp55 binding site. Finally, for P7, we found two variants of uncertain significance with minor allele frequency below 1% and in trans with the exonic variant. One variant was found in the promoter region of ACADM NC_000001.11(NM_000016.5):c.-440T>C and the other was a deep intronic variant NC_000001.11(NM_000016.5):c.945+803A>C.

Functional genomics reclassified three new variants as pathogenic

In addition to the RNA analysis, we assessed the effect of the SNVs detected in AGL, ACAT1, and ACADM, as well as the SV identified in SLC2A1, through functional genetic tests.

To analyze the intronic variant in AGL, a transcriptional profile analysis was conducted. The results suggest that the variant NC_000001.11(NM_000642.3):c.3259+927A>G results in a 105 bp PE insertion (Supplementary Fig. 1A) r.3259_3260ins[3259 + 818_3259 + 922] p.(Gly1087_Leu1532delinsAspPheHisLeuThrVal). Although this PE insertion is in frame, it generates a premature stop codon that presumably activates NMD.

A minigene analysis was done for the intronic variant detected in ACAT1 in P6. The results suggest that the variant NC_000011.10(NM_000019.4):c.941-60T>C leads to the skipping of the 65 bp of exon 10 of ACAT1 (Supplementary Fig. 1B).

For the identified ACADM promoter variant (NC_000001.11(NM_000016.5):c.-440T>C), the luciferase reporter assay showed slightly reduced transcriptional activity of this allele (data not shown). However, these results do not fully justify the reduced expression observed in the transcriptional profile (Fig. 1D).

To investigate the potential effect of the LINE insertion detected 7.6 kb into the SLC2A1 3’ region, we first investigated the 3D structure of this locus, exploiting available micro-HiC data [29, 30]. The SLC2A1 region is organized in a TAD delimited by a single CTCF binding site (CBS) in a reverse orientation in its 3’ side, which interacts with two forward-oriented CBS of the 5’ TAD boundary (Fig. 3A, B; red arrows), in agreement with the loop extrusion model of TAD establishment [31]. The CBS of the 3’ TAD border also contacts the forward-oriented CBS near the SLC2A1 TSS and in 5’ of the TAD (Fig. 3A, B; yellow arrows). Analysis of SLC2A1 promoter interactions by 4Cseq in healthy individuals’ fibroblasts (controls), confirmed that SLC2A1 contacts are largely restrained within its TAD, with the largest fraction of interactions spanning the locus and ~21 kb upstream of the gene TSS (Fig. 3C, Supplementary Fig. 2A, B). Besides, the SLC2A1 promoter also strongly contacts a region 80 kb upstream (hereafter referred to as 5’ distal region) and near the CBS of the TAD border. According to ENCODE epigenetic profiles [32], this region contains several sequences enriched in the H3K27 acetylation mark (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Fig. 2A, B), a modification associated with active CRE [33].

A,B Micro-HiC heatmap in HFFc6 (A) and chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled to sequencing (ChIPseq) profile for CTCF in NHLF cells from ENCODE (B). CTCF binding sites (CBS) with forward (red arrows) or reverse orientation (blue arrows) are displayed below the heatmap. The CBS orientation was predicted using the CTCFBS prediction tool [46]. The SLC2A1 exonic structure is represented by blue boxes and arrows in the intronic regions indicate transcription orientation. The LINE insertion detected in P4 (L) is marked by a yellow box and dashed line. C,E Mean 4Cseq normalized profiles of SLC2A1 promoter (C, upper graphs) or the SLC2A1-CRE (cis regulatory elements) cluster (E, upper graphs) viewpoints obtained from control and P4 fibroblasts. Each VP and the corresponding excluded region are marked by a red asterisk. The profiles include the average of two technical replicates for each sample and two biological replicates. The lower graph depicts the difference in contact score between the P4 sample and the mean of the controls. D ENCODE ChIPseq profiles for the H3K27ac epigenetic mark of different cell lines. The CRE constituting the cluster in the SLC2A1 5’ distal region are depicted by green rectangles.

In P4 fibroblasts, the SLC2A1 promoter contacts with its 5’ distal region were strongly reduced compared to controls (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Fig. 2A, B, D). Conversely, proximal locus interactions tended to increase (although not statistically significantly), suggesting a more closed chromatin conformation. To confirm these results, we used as viewpoint (VP) the cluster of CRE located in the 5’ distal region (hereafter referred to as SLC2A1-CRE). This region strongly contacts the SLC2A1 promoter and gene locus in controls (Fig. 3E; Supplementary Fig. 2C, E), while its interactions were significantly reduced in those of P4 (Supplementary Fig. 2C, E). Interestingly, the SLC2A1-CRE VP increased its interactions with the region immediately 5’ of the LINE insertion (Fig. 3E; Supplementary Fig. 2C, E). Of note, this tendency was observed in the comparison of P4 sample with that of either control, but it reached statistical significance only against control 1 or in P4 vs control averaged comparisons (Supplementary Fig. 2E), likely due to the variability in 4Cseq experiments. Instead, an equivalent region located on the opposite side of the SLC2A1-CRE VP (Supplementary Fig. 2E) did not show any clear tendency among conditions, supporting the specificity of the observed differences.

Thus, our data suggest that the region located 80 kb upstream of the SLC2A1 TSS contains a CRE cluster likely regulating SLC2A1 expression and that the LINE insertion correlates with a decrease in the interactions between SLC2A1 and this CRE cluster via rewiring of the contacts of the latter towards the vicinity of the LINE (Fig. 4).

In control fibroblasts, the SLC2A1 promoter contacts a cis-regulatory element (CRE) cluster located 80 kb upstream, likely via the looping of the CTCF binding site (CBS) of the 3’ topologically associating domain (TAD) border with the CBS of near the gene transcription start site (TSS), as well as those at the 5’ TAD border. This may result in the establishment of an active conformational hub (green shadowed circle) involving the SLC2A1 locus (light blue box) and promoter, as well as proximal and distal enhancers (green circles; for simplicity, CRE located within the SLC2A1 locus itself are not depicted), promoting or sustaining high SLC2A1 transcription. Instead, in P4, the CRE cluster contacts are displaced towards the vicinity of the LINE insertion at the TAD border, possibly by CTCF-mediated looping between the CBS near the CRE cluster and those of the LINE. This leads to a reduction of CRE cluster-SLC2A1 promoter contacts, and possibly, to an overall alteration of the structure of the conformational hub, weakening SLC2A1 transcription.

Discussion

Advances in sequencing technologies have led to the genetic diagnosis of many persons suspected to have a genetic disease. Nevertheless, diagnostic yield remains lower than expected [34]. Combining newer tools like LRS with multi-omics and functional analyses may help resolve more cases and shorten the diagnostic odyssey in IMD.

In this study, we show that applying adaptive sampling with ONT LRS makes it possible to phase and identify clinically relevant variants [35]. This approach is highly versatile, as it can target any genomic region without requiring prior assay design. As has been described by focusing LRS on specific genes, the method reduces both experimental and analytical barriers, ultimately facilitating its clinical adoption and contributing to a more comprehensive view of disease-associated variation [3].

In IMD, the presence of a biochemical biomarker eases the focus of genetic technologies to a limited number of genes. IMDs are identified in the neonatal screening program or after clinical suspicion and subsequent analysis by biochemical genetics. Nevertheless, molecular-genetic confirmation is needed. In our cohort of unsolved individuals, LRS has revealed the missing hit in six of them. Our results confirm that targeted LRS may be an adequate “next step” after genetic testing in the clinical setting when a candidate locus of interest is known. This technique has increased sensitivity to detect SV over srGS [35].

One of the major problems to conclude a definite genetic diagnosis is the assessment of the clinical relevance of VUS. This is more evident when an SV is detected due to the lack of public databases of population frequencies. Thus, different orthogonal analyses should be applied to validate these variants. RNA-Seq is one of the most powerful systems to evaluate variants affecting gene expression or splicing [36] if the gene is expressed in accessible tissues. Indeed, using the results of the RNA-Seq, we were able to identify defects in transcription (low expression levels, splicing defects, or ASE) that guided an LRS approach and, in the end, validated the clinical effect of the variants. The transcriptional defects have been related to intronic and promoter SNVs, duplications, or TE insertions.

In our knowledge, this is the first time the insertion of a TE has been reported to cause an IMD. Two of them were found inside the gene, one in exon 10 of GYS2, and the other was present in intron 8 of PEX1. This type of movement has been associated with pathology by inserting pseudoexons, leading to degradation via NMD [37]. The third TE insertion was detected 7.6 kb downstream of SLC2A1 and could explain the reduction of the gene expression [38]. This result demonstrates that the movement of TE is a more common cause of disease than initially thought and that it should be implemented in the clinical setting in the future.

Finally, the use of LRS allows the detection of SNVs, indicating the potential use of this technology to identify all types of variants. We have identified SNVs affecting the splicing process in AGL and ACAT1. For the case of P6, the re-analysis of ES data allowed to detect the intronic variant in ACAT1 in the visualization of BAM files, although it was not correctly called in the variant calling files (VCF). The filtering strategy to obtain the VFC limited variant detection to exons ±10 bp, therefore, leaving NC_000011.10(NM_000019.4):c.941-60T>C undetected. Thus, in autosomal recessive disorders, when a previously pathogenic variant is identified in a gene associated with the phenotype of a participant, all ES data should be carefully re-evaluated to ensure no disease-causing changes are being missed.

Predicting the effect of novel SVs is a complicated mission, especially when they fall outside the coding regions of genes [39]. Our 4Cseq experiments demonstrate that, in P4 fibroblasts, the SLC2A1 promoter shows a significant decrease in contacts with a cluster of sequences enriched in enhancer epigenetic marks. This suggests that this region contributes to SLC2A1 regulation and may explain the decrease in SLC2A1 expression in P4. Although the magnitude of these alterations is relatively modest, this may be due to two factors. First, the patient is heterozygous for the LINE insertion, so the interactions of the other allele likely attenuate the observed differences. Second, the SLC2A1-CRE cluster may be active in a cell-type-specific manner, as suggested by ENCODE H3K27ac profiles, which show particularly low activity in fibroblasts (NHLF cells). While gene-enhancer contacts can occur across cell types, their strength often depends on enhancer activity [40]. Thus, experimenting with a cell type where the CRE cluster is active would likely reveal stronger effects. This also suggests that, although disruption of TAD internal organization may account for the transcriptional effects observed in patient-derived fibroblasts, the pathological phenotype of P4 may result from context-specific SLC2A1 downregulation.

TE can shape gene regulatory landscapes through different mechanisms [41], including serving as CRE, or altering chromatin organization by bearing CBS [42]. Our 4Cseq data show that the SLC2A1 promoter does not significantly change its interactions with the region near the LINE insertion in P4, unlike observed with the SLC2A1-CRE VP. This suggests that the LINE is unlikely to directly regulate SLC2A1. Instead, we identified putative CBS within the LINE sequence (Supplementary Fig. 3), although with some variation across LRS results. Despite confirming CTCF binding at the LINE is technically challenging, the presence of CBS near both the CRE cluster and the LINE may explain the observed contact rewiring. Nonetheless, other mechanisms may account for this phenomenon, such as the enhancer RNA- or TE-derived upstream antisense RNA–mediated looping described for Alu elements [43].

Finally, our results expand previous studies emphasizing the role of chromatin organization and gene-enhancer interactions in disease [7], and highlight the value of chromatin conformation capture methods for assessing the functional impact of novel genetic variants.

In the evolving landscape of precision and preventive medicine, several neonatal genomic sequencing pilot projects are exploring the potential use of ES or srGS to expand the number of detectable conditions beyond those identified by mass spectrometry and to enable early treatment before symptom onset [44]. Because these pilot genomic sequencing efforts mainly rely on short-read technologies, some of the variant types identified in our study would not be assessed using these approaches. Importantly, this does not affect the performance of established biochemical newborn screening, and no children currently identified through biochemical screening would be missed. However, our results show that some pathogenic variants associated with disorders not currently detected by biochemical newborn screening are challenging to capture with short-read ES or srGS, whereas they can be resolved using long-read sequencing. Our findings highlight the value of srGS and LRS for detecting pathogenic variants in non-coding regions and non-standard variant types [45] and point to future needs such as pangenome references and population-specific databases to fully enable these technologies in clinical and eventually newborn contexts.

In conclusion, this study has narrowed the diagnostic gap in IMD by integrating multiple omics data. We have expanded the mutational spectrum, identifying non-standard disease-causing variants. This enhanced knowledge will contribute to improving the sensitivity and specificity of genetic diagnosis for IMDs.

Data availability

All the new variants have been submitted to the ClinVar database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) with the following accession numbers: SUB15762227, SUB15762348, SUB15762360, SUB15762410, SUB15762443, SUB15762466, SUB15762472 and SUB15768776. The data supporting the results of this study are available in the article and Supplementary Information or can be made available by contacting the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ferreira CR, Rahman S, Keller M, Zschocke J. ICIMD Advisory Group. An international classification of inherited metabolic disorders (ICIMD). J Inherit Metab Dis. 2021;44:164–77.

Forny P, Bonilla X, Lamparter D, Shao W, Plessl T, Frei C, et al. Integrated multi-omics reveals anaplerotic rewiring in methylmalonyl-CoA mutase deficiency. Nat Metab. 2023;5:80–95.

Miller DE, Sulovari A, Wang T, Loucks H, Hoekzema K, Munson KM, et al. Targeted long-read sequencing identifies missing disease-causing variation. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108:1–14.

Truty R, Ouyang K, Rojahn S, Garcia S, Colavin A, Hamlington B, et al. Spectrum of splicing variants in disease genes and the ability of RNA analysis to reduce uncertainty in clinical interpretation. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108:696–708.

Cramer P. Organization and regulation of gene transcription. Nature. 2019;573:45–54.

Ferrer J, Dimitrova N. Transcription regulation by long non-coding RNAs: mechanisms and disease relevance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25:396–415.

Akdemir KC, Le VT, Chandran S, Li Y, Verhaak RG, Beroukhim R, et al. Disruption of chromatin folding domains by somatic genomic rearrangements in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2020;52:294–305.

Schobers G, Derks R, Den Ouden A, Swinkels H, Van Reeuwijk J, Bosgoed E, et al. Genome sequencing as a generic diagnostic strategy for rare disease. Genome Med. 2024;16:32.

van Dijk EL, Jaszczyszyn Y, Naquin D, Thermes C. The third revolution in sequencing technology. Trends Genet. 2018;34:666–81.

Sanford Kobayashi E, Batalov S, Wenger AM, Lambert C, Dhillon H, Hall RJ, et al. Approaches to long-read sequencing in a clinical setting to improve diagnostic rate. Sci Rep. 2022;12:16945.

Hollox EJ, Zuccherato LW, Tucci S. Genome structural variation in human evolution. Trends Genet TIG. 2022;38:45–58.

Hancks DC, Kazazian HH. Roles for retrotransposon insertions in human disease. Mob DNA. 2016;7:9.

Soto DC, Uribe-Salazar JM, Shew CJ, Sekar A, McGinty SP, Dennis MY. Genomic structural variation: a complex but important driver of human evolution. Am J Biol Anthropol. 2023;181:118–44.

Chénais B. Transposable elements and human diseases: mechanisms and implication in the response to environmental pollutants. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:2551.

Wells JN, Feschotte C. A field guide to eukaryotic transposable elements. Annu Rev Genet. 2020;54:539–61.

Bourque G, Burns KH, Gehring M, Gorbunova V, Seluanov A, Hammell M, et al. Ten things you should know about transposable elements. Genome Biol. 2018;19:199.

Kagawa T, Oka A, Kobayashi Y, Hiasa Y, Kitamura T, Sakugawa H, et al. Recessive inheritance of population-specific intronic LINE-1 insertion causes a rotor syndrome phenotype. Hum Mutat. 2015;36:327–32.

Casas-Alba D, Hoenicka J, Vilanova-Adell A, Vega-Hanna L, Pijuan J, Palau F. Diagnostic strategies in patients with undiagnosed and rare diseases. J Transl Genet Genomics. 2022;6:322–32.

Ellingford JM, Ahn JW, Bagnall RD, Baralle D, Barton S, Campbell C, et al. Recommendations for clinical interpretation of variants found in non-coding regions of the genome. Genome Med. 2022;14:73.

Martin S, Heavens D, Lan Y, Horsfield S, Clark MD, Leggett RM. Nanopore adaptive sampling: a tool for enrichment of low abundance species in metagenomic samples. Genome Biol. 2022;23:11.

Ueno Y, Arita M, Kumagai T, Asai K. Processing sequence annotation data using the Lua programming language. Genome Inform Int Conf Genome Inform. 2003;14:154–63.

Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:3094–3100.

Sedlazeck FJ, Rescheneder P, Smolka M, Fang H, Nattestad M, Von Haeseler A, et al. Accurate detection of complex structural variations using single-molecule sequencing. Nat Methods. 2018;15:461–8.

Zheng Z, Li S, Su J, Leung AW-S, Lam T-W, Luo R. Symphonizing pileup and full-alignment for deep learning-based long-read variant calling. Nat Comput Sci. 2022;2:797–803.

Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–6.

Freeman PJ, Hart RK, Gretton LJ, Brookes AJ, Dalgleish R. VariantValidator: accurate validation, mapping, and formatting of sequence variation descriptions. Hum Mutat. 2018;39:61–68.

Tejedor JR, Soriano-Sexto A, Beccari L, Castejón-Fernández N, Correcher P, Sainz-Ledo L et al. Integration of multi-omics layers empowers precision diagnosis through unveiling pathogenic mechanisms on maple syrup urine disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1002/jimd.12829.

Bravo-Alonso I, Navarrete R, Vega AI, Ruíz-Sala P, García Silva MT, Martín-Hernández E, et al. Genes and variants underlying human congenital lactic acidosis—from genetics to personalized treatment. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1811.

Krietenstein N, Abraham S, Venev SV, Abdennur N, Gibcus J, Hsieh T-HS, et al. Ultrastructural details of mammalian chromosome architecture. Mol Cell. 2020;78:554–565.e7.

Sikorska N, Sexton T. Defining functionally relevant spatial chromatin domains: it is a TAD complicated. J Mol Biol. 2020;432:653–64.

Davidson IF, Bauer B, Goetz D, Tang W, Wutz G, Peters J-M. DNA loop extrusion by human cohesin. Science. 2019;366:1338–45.

ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74.

Creyghton MP, Cheng AW, Welstead GG, Kooistra T, Carey BW, Steine EJ, et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21931–6.

Stenton SL, Kremer LS, Kopajtich R, Ludwig C, Prokisch H. The diagnosis of inborn errors of metabolism by an integrative “multi-omics” approach: a perspective encompassing genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2020;43:25–35.

Zhao X, Collins RL, Lee W-P, Weber AM, Jun Y, Zhu Q, et al. Expectations and blind spots for structural variation detection from long-read assemblies and short-read genome sequencing technologies. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108:919–28.

Peymani F, Farzeen A, Prokisch H. RNA sequencing role and application in clinical diagnostic. Pediatr Investig. 2022;6:29–35.

Pfaff AL, Singleton LM, Kõks S. Mechanisms of disease-associated SINE-VNTR-Alus. Exp Biol Med. 2022;247:756–64.

de Bruijn SE, Fiorentino A, Ottaviani D, Fanucchi S, Melo US, Corral-Serrano J, et al. Structural variants create new topological-associated domains and ectopic retinal enhancer-gene contact in dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet. 2020;107:802–14.

Dirix M, Gribouval O, Arrondel C, Benjelloun S, Boyer O, Charbit M, et al. Overcoming the challenges associated with identification of deep intronic variants by whole genome sequencing. Clin Genet. 2023;103:693–8.

Ghavi-Helm Y, Klein FA, Pakozdi T, Ciglar L, Noordermeer D, Huber W, et al. Enhancer loops appear stable during development and are associated with paused polymerase. Nature. 2014;512:96–100.

Gebrie A. Transposable elements as essential elements in the control of gene expression. Mob DNA. 2023;14:9.

Choudhary MNK, Quaid K, Xing X, Schmidt H, Wang T. Widespread contribution of transposable elements to the rewiring of mammalian 3D genomes. Nat Commun. 2023;14:634.

Wen X, Zhong S. Alu transposable elements rewire enhancer-promoter network through RNA pairing. Mol Cell. 2023;83:3234–5.

Ziegler A, Koval-Burt C, Kay DM, Suchy SF, Begtrup A, Langley KG, et al. Expanded newborn screening using genome sequencing for early actionable conditions. JAMA. 2025;333:232–40.

Sinha S, Rabea F, Ramaswamy S, Chekroun I, El Naofal M, Jain R, et al. Long read sequencing enhances pathogenic and novel variation discovery in patients with rare diseases. Nat Commun. 2025;16:2500.

Ziebarth JD, Bhattacharya A, Cui Y. CTCFBSDB 2.0: a database for CTCF-binding sites and genome organization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D188–94.

Funding

This work was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), European Regional Development Fund [PI22/00699] to BP. The CIBER de Enfermedades Raras is an initiative from the ISCIII (Spain). CEDEM gratefully acknowledges the support of Fundación Ramón Areces. R. H. Tresbach was awarded a grant from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq - Brasil - Process n. 200811/2024

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Alejandro Soriano-Sexto: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing – original draft, visualization. Obdulia Sánchez-Lijarcio: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation. Leonardo Beccari: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation. Natalia Castejón-Fernández: validation, formal analysis, investigation. Fátima Leal: validation, formal analysis, investigation. Patricia Alcaide: validation, formal analysis, investigation. Belén de la Morena-Barrio: methodology, validation. María del Pilar Bahíllo-Curieses: resources. Patricia Correcher: resources. Laura López: resources. Rafael Hencke-Tresbach: validation, formal analysis, investigation. Elena Martín-Hernández: resources. Raquel Yahyaoui: resources. Magdalena Ugarte: resources. Pilar Rodríguez-Pombo: conceptualization, supervision. Belén Pérez: conceptualization, resources, writing – review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (CEI-1029-2655). All participants or their legal guardians have signed an informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soriano-Sexto, A., Sánchez-Lijarcio, O., Beccari, L. et al. Expanding the genetic landscape of inherited metabolic diseases using long-read sequencing and transcriptomic profiling. Eur J Hum Genet (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-025-01995-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-025-01995-7