Abstract

Background/Objective

To provide a large-scale analysis on the demographics and ocular comorbidities in Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) patients in the US.

Subjects/Methods

This is an exploratory cross-sectional study comparing medical records of EDS patients to the general population on demographic variables and ICD-10 ocular diagnoses. A research platform with de-identified EHR data of over 99 million patients across 60 healthcare organizations was utilized. Groups were stratified by 30-year age groups. Patients aged 0–61+ with an ICD-10 diagnosis of EDS (76,526), the general platform population aged 0–61+ (99,836,639), and patients with a concurrent ICD-10 ocular diagnosis were queried to determine the prevalence of EDS across demographic variables, ocular disease, and odds of ocular disease. Statistical analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel and R studio, using p < 0.01 and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

An EDS diagnosis was most prevalent in white females aged 0–30 years old (259.6 per 100,000). The majority of ocular diagnoses were more prevalent in the 0–60-year-old EDS population compared to the general population including myopia (5227.0 per 100,000) and dry eye (4211.6 per 100,000). Overall, diagnoses of angioid streaks (POR 18.72, 95% CI 10.32, 33.94) and idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) (POR 18.43, 95% CI 17.51, 19.39) showed the highest increased odds in patients with EDS while significantly decreased odds were shown for type 2 diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, and retinal vein occlusion.

Conclusions

EDS was associated with increased odds of having a concurrent ocular pathology, suggesting that, upon diagnosis of EDS, referral to ophthalmology may be valuable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) is a rare genetic disorder of collagen and extracellular matrix proteins. It has a reported prevalence between 1 in 5000 and 1 in 100 000 [1, 2]. This value is likely an underestimation due to the wide spectrum of clinical presentations in EDS, attributed to variants in 20 genes [3, 4]. The variable expressivity of these genes creates 13 different subtypes of EDS, most recently classified by the International EDS Consortium in 2017 [5]. Because the implicated genes encode for fibrillar collagen and collagen modifying enzymes, the manifestations of the EDS subtypes have common features: joint hypermobility, skin hyperelasticity and hyperextensibility, abnormal wound healing, and tissue fragility [3, 6,7,8,9]. The ubiquitous nature of connective tissue entails that EDS affects nearly every organ system in the body. Thus, although the most widely recognized systems in EDS are the musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and dermatological systems, a diagnosis of EDS warrants an extensive work-up to assess the integrity of connective tissue elsewhere [3, 10,11,12,13].

Little is known regarding the ocular manifestations of EDS with most studies being case studies or series. Perez-Roustit et al. published a series of 21 patients with EDS and reported ophthalmological signs in 90% of their cohort including dry eye, blue sclera, and high myopia [14]. Other studies detail findings of irregular astigmatism, conjunctivochalasis, and ectopia lentis [15,16,17]. One prospective, cross-sectional study of 44 eyes with EDS of the hypermobile subtype reported xerophthalmia, steeper corneas, myopia, lens opacity, and vitreous abnormalities [18]. To the best of our knowledge, the average sample sizes of studies detailing ocular features in EDS patients are less than 100 and there was a lack of consensus in the ocular findings reported [19, 20]. Despite the spectrum of ocular findings in EDS, the pathogenesis of each condition is likely rooted in abnormal collagen fibrillogenesis that affects the collagenous structures of the eye.

From an ophthalmic surgery standpoint, a case study of 467 EDS patients found that 24% of the cohort required ophthalmic surgery, including but not limited to strabismus, refractive, retinal, and cataract surgery [21]. Nearly 50% of these patients experienced at least one complication. Awareness of this post-op complication rate could shape surgical decision making, yet 76% of those who underwent surgery were not yet diagnosed with EDS. Providing additional information in the literature about EDS ocular phenotypes could help surgeons screen patients prospectively for EDS, and also expedite a diagnosis that may affect surgical planning.

In the setting of a rare disease such as EDS, it is furthermore difficult to diagnose the relevant subtype of disease as clinical criteria and genetic markers continue to evolve [22,23,24]. Not only does this pose a difficulty for ophthalmologists when evaluating EDS patients, but it also generates uncertainty in counselling patients on what their EDS diagnosis means for their eye health. The use of aggregated electronic health records (EHR) enables an unprecedented ability to analyse the largest group of EDS patients to date. Thus, the primary purpose of this exploratory analysis was to provide updated information on EDS patient demographics and ocular comorbidities.

Materials/subjects and methods

This retrospective, cross-sectional study was conducted using the TriNetX US Collaborative Network (TriNetX, LLC (www.trinetx.com)), a federated health research platform that aggregates de-identified EHR data of over 99 million patients across 60 healthcare organizations (HCOs). TriNetX, LLC is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the US federal law which protects the privacy and security of healthcare data, and any additional data privacy regulations applicable to the contributing HCO. The process by which the data is de-identified is attested to through a formal determination by a qualified expert as defined in Section §164.514(b)(1) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Because this study used only de-identified patient records, this study was deemed exempt by the Western Institutional Review Board.

Data was collected on July 1, 2024 with a restricted timeframe of 1/1/2012-5/1/2024. Additional data was collected on February 11, 2025 to address reviewer comments. All encounter diagnosis data was extracted using International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Ninth/Tenth Revision (ICD-9/10) codes as the platform automatically groups these together. Of note, data reporting throughout this manuscript is not a measure of the true study populations as the platform relies on existing data within EHR systems. Thus, in this paper, an EDS patient is defined as a patient who has a recorded ICD-10 diagnosis of EDS, the general population is defined as any individual with a visit in the EHR irrespective of an associated ICD-10 diagnosis, and an ocular condition is defined as a recorded ICD-10 diagnosis of this condition.

The first aim of this study was to highlight how the EDS patient population may differ from the general population by demographic factors of age, gender, and race. The EDS patient cohort was defined by any ICD-10 encounter diagnosis code Q79.6 and compared to the entire TriNetX population in the US Analytic Network. Each cohort was stratified by 30-year age cohorts to capture nuances in this population who is typically in adolescence at time of first diagnosis and has a significantly shortened life expectancy at 48 years [25, 26]. Within each cohort, the mean age of the study group (and associated standard deviation) was collected to assist in drawing comparative conclusions from the data. Within each age group, gender and race/ethnicity stratifications were also added.

Secondarily, this study aimed to understand the recorded prevalence of ocular diagnoses in EDS patients compared to the general population through obtaining the platform’s prevalence data on multiple ocular conditions. The equation used for the prevalence of an ocular condition in EDS per 100000 was: \(\frac{{{Prevalence\; of\; ocular\; disease}}_{{in\; EDS}}}{{Total\; EDS\; population}}x100000.\) Conditions commonly reported in the EDS literature, conditions with increased risk with cardiovascular disease, and other common retinal conditions were included. All ICD-10 encounter diagnoses codes for these conditions are listed in Table 1. Age was considered as a confounding variable due to the decreased life expectancy of the EDS group, and the increased average age of diagnosis for several conditions examined. To account for this, the prevalence of these conditions was obtained at the same 30-year age stratification rate. The platform automatically rounds any counts 1–10 to protect patient privacy. Therefore, ocular conditions that resulted in less than or equal to 10 patient cases in the platform were omitted from calculations and figures to prevent presentation of misleading data.

To assess whether EDS patients were at increased odds for any of the studied ocular conditions, a contingency table was used for the prevalence odds ratio (POR) calculation. With age stratification, some ocular conditions too rare to stratify by age were rounded by the platform, and thus excluded for the analysis. PORs and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using Microsoft Excel and R Studio. Forest plots were created in R Studio. P values were calculated for all prevalence estimates using a chi-squared 2-sided test. A significance threshold of 0.01 or less was used. STROBE guidelines were followed in this study and writeup.

Results

At the time of data collection, the total number of records with an EDS diagnosis was 76526 and the total data population in the US Collaborative Network was 99 836 639.

EDS patient demographics

Across each race stratification, females had a greater prevalence of EDS diagnosis compared to men (Table 2). Records of an EDS diagnosis were most prevalent in white females 30 years or younger with a prevalence of 259.6 per 100,000. In the 30-year age cohorts, the total prevalence of EDS records per 100,000 was respectively 110.8, 93.8, and then a steep drop in the 61+ cohort to 17.1. When stratifying by gender and age, the recorded EDS prevalence for females aged 0–30 and 31–60 were comparable at respectively 167.3 and 150.0. There was a drop in the prevalence of females 61+ years old diagnosed with EDS at 31.7 per 100,000. This trend of decreased prevalence of an EDS diagnosis at 61+ years old was seen in all races/ethnicities when female gender was isolated. Although male patients had a much smaller EDS diagnosis prevalence compared to females, an EDS diagnosis was also most prevalent in males aged 0–30 across all races investigated (Table 2).

EDS and ocular conditions

Table 3 showcased the overall prevalence of patients with ICD-10 encounter diagnoses for EDS and ocular conditions, and the prevalence within the 30-year age cohorts. The mean age of patients diagnosed with EDS (22 ± 6 years of age) was older than the platform’s general population (17 ± 8 years of age) only for the 0–30 age-cohort. Overall, 9/23 (40%) included ocular diagnoses were significantly more prevalent in EDS diagnosed patients compared to the total population. Specifically, patients with recorded diagnoses of myopia and dry eye syndrome had the highest prevalence per 100,000 at 5227.0 and 4211.6 respectively. Notably, diagnoses of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) and glaucoma demonstrated marked prevalence per 100,000 at 1995.4 and 1532.8. ICD-10 encounter diagnoses for several ocular conditions were found to have significantly lower prevalences among patients diagnosed with EDS than the overall population including: diabetic retinopathy (DR) secondary to type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2 DR), non-neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and neovascular AMD (Table 3).

In the 0–30 year age cohort, 11/12 (92%) ocular diagnoses were significantly more prevalent in patients diagnosed with EDS compared to the overall population. Those ICD-10 encounter diagnosis codes that remained more prevalent in patients diagnosed with EDS were myopia (prevalence in EDS per 100,000: 2301.2), dry eye syndrome (761.8), IIH (670.4), and glaucoma (260.0). In the 31–60 year age cohort, 15/18 (83%) ocular diagnoses were significantly more prevalent in patients diagnosed with EDS compared to the overall population. ICD-10 encounter diagnoses with markedly increased prevalence in this cohort were similarly myopia (2444.9), dry eye syndrome (2485.4), IIH (1263.6), and glaucoma (734.4). Lastly, in the 61+ year old cohort, 4/15 (27%) ocular diagnoses were significantly more prevalent in patients diagnosed with EDS compared to the overall population. In this older group of patients, the most prevalent ICD-10 encounter diagnosis was dry eye syndrome (964.4), followed by glaucoma (538.4) and myopia (480.9).

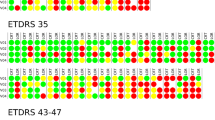

After calculating the PORs between patients diagnosed with EDS and the overall population, 40% of ocular diagnoses continued to be significantly increased in EDS patients. Notably, the highest PORs were for recorded ICD-10 diagnoses of angioid streaks (POR 18.72, 95% CI 10.32, 33.94, p value 0) and IIH (POR 18.43, 95% CI 17.51, 19.39, p value 0). Other ocular diagnoses with increased PORs in EDS records were myopia (POR 4.40, 95% CI 4.26, 4.54, p value 0), degenerative myopia (POR 3.48, 95% CI 2.94, 4.12, p value 0), dry eye syndrome (POR 3.89, 95% CI 3.76, 4.03, p value 0), and carotid cavernous fistula (POR 3.99, 95% CI 3.70, 4.31, p value 0). On the other hand, patients diagnosed with EDS were at significantly decreased odds for multiple ocular diagnosis including T2 DR and AMD (p < 0.01) (Fig. 1a).

a Forest plot depicting prevalence odds ratios (PORs) of various ocular diagnoses in the overall EDS population. b Forest plot depicting prevalence odds ratios (PORs) of various ocular diagnoses in the EDS patients 0–30 years old. c Forest plot depicting prevalence odds ratios (PORs) of various ocular diagnoses in the EDS patients 31–60 years old. d Forest plot depicting prevalence odds ratios (PORs) of various ocular diagnoses in the EDS patients 61+ years old.

When stratifying by age, only ocular diagnoses with >10 records were included in the analysis. In the 0–30 age cohort, the POR was significantly increased for 10/12 conditions (83%) and significantly decreased for 1/12 conditions (8%). In 0–30-year-old patients diagnosed with EDS, the ocular diagnoses with markedly increased odds were carotid cavernous fistula (POR 17.21, 95% CI 14.18, 20.88, p value 0) and IIH (POR 16.65, 95% CI 15.25, 18.18, p value 0). ROP showed decreased odds in patients diagnosed with EDS 0–30 years old (POR 0.39, 95% CI 0.27, 0.56, p value 0). In the 31–60 age cohort, EDS records were at significantly increased odds of having a recorded diagnosis for 72% of the included conditions, while having significantly decreased odds of 1/18 (6%) of the diagnoses. The ICD-10 diagnosis for IIH showed the highest increased odds (POR 16.44, 95% CI 15.42, 17.54, p value 0) but the ICD-10 diagnosis for T2 DR showed significantly decreased odds (POR 0.68, 95% CI 0.55, 0.84, p value 0.00041). Lastly, in the 61+ age cohort, 12/15 (80%) of ocular diagnoses were significantly increased in patients diagnosed with EDS, with the ICD-10 diagnosis for IIH consistently showing the highest increased odds. All data corresponding to the PORs, CIs, and p values of ocular ICD-10 encounter diagnoses in EDS by age can be found in Fig. 1b–d.

Discussion

This exploratory study used the TriNetX platform to examine the demographics of EDS and prevalence of ocular conditions in patients with recorded diagnoses of EDS, distributed across the age cohorts 0–30, 31–60, and 61 + . We found an EDS diagnosis was most prevalent in white females across all age groups, and the age of first ICD-10 encounter diagnosis was heavily skewed towards the 0–30 age cohort with a prevalence of 259.6 per 100,000. This data shows that EDS is frequently diagnosed in the early decades of life. As many included ocular ICD-10 diagnoses increase with age, the prevalence and risk in EDS patients may be underestimated compared to age-matched comparators.

Yet, many of the included ocular diagnoses were more prevalent in EDS records, especially among patients 0–60 years old. Overall, patients diagnosed with EDS had the highest prevalence of ICD-10 diagnoses for myopia (prevalence in EDS per 100,000: 5227.0), dry eye syndrome (4211.6), IIH (1995.4), and glaucoma (1532.8). Patients diagnosed with EDS had the highest PORs for diagnoses of angioid streaks (POR 18.72, CI 10.32, 33.94, p value 0) and IIH (POR 18.43, CI 17.51, 19.39, p value 0), while having decreased odds for diagnoses of T2 DR, AMD, and hypertensive retinopathy. Across every EDS age group, IIH consistently demonstrated the highest increased odds, and carotid cavernous fistula emerged as one of the most significant conditions in patients aged 0–30 (POR 17.21, CI 14.18, 20.88, p value 0).

Our data suggests that an EDS diagnosis has significant implications on ocular health. The altered mechanisms of procollagen formation, extracellular matrix (ECM) bridging molecules, and glycosaminoglycan synthesis contribute to the complex pathogenesis of EDS and its subtypes [27]. Collagenous structures of the eye include the cornea, sclera, vitreous body, lens capsule, retina, and choroid [28, 29]. Thus, these widespread ocular pathologies with demonstrated increased odds in EDS records confirm that EDS collagen malformations extend systemically and a referral to ophthalmology should not be undermined.

Confirming smaller studies on ocular manifestations of EDS, we found increased odds of ICD-10 diagnoses for IIH (overall POR 18.43), myopia (4.40), degenerative myopia (3.48), carotid cavernous fistula (3.99), and dry eye (3.89) in both our overall and age-stratified patient groups (Fig. 1a–d). Although angioid streaks had a markedly elevated POR (18.72) in the overall group, there were only 11 EDS records with angioid streaks. Additionally, there exist controversial associations between angioid streaks and EDS in the literature which can introduce sources of misdiagnosis and an inadvertent inflation of its true prevalence rate in this population [30,31,32]. Combined with the rarity of this diagnosis, the POR for angioid streaks may be inadvertently skewed, making this association an area for future study.

Myopia and degenerative myopia are two of the most commonly reported ocular findings in EDS, yet the literature remains inconclusive with contradictory findings [1, 18, 33]. Our findings show that patients diagnosed with EDS have a higher POR of myopia compared to the general population. Myopia is typically diagnosed in childhood, and adult-onset myopia progression can be observed up to the 5th decade of life [34]. Given that the mean age of EDS records was higher than its general comparator in the 0–30 age cohort, when a myopia diagnosis is most common, the impact of our findings is particularly pronounced. The proposed pathogenesis involves EDS mediated changes to the vitreous ECM secondary to decreased bridging molecule integrity and altered scleral composition secondary to abnormal collagen formation. Both ECM and scleral structure regulate the axial length of the eye, and therefore EDS impacts on both of these components can lead to myopia and its progressively degenerative subtypes [18, 35]. Additionally, animal studies examining EDS mouse models have shown abnormal collagen structure in the cornea, causing changes to the biomechanical properties of the cornea [36, 37]. Others have also found that classic EDS patients have both thinner and steeper corneas [19, 38,39,40]. Such corneal changes may also explain the pathophysiology of increased myopia seen in EDS.

Villani et al. and Gharbiya et al. hypothesize over the role of EDS in dry eye syndrome, which we also found to be increased in patients diagnosed with EDS. Increased ocular surface disease index scores and tear film instability in EDS patients suggests a role in the altered collagen of the ocular surface epithelial cells [19, 41]. Alternatively, altered ECM of the lacrimal glands may explain the association between EDS and dry eyes [18].

The increased odds of an IIH diagnosis in EDS may be due to altered dynamics of cerebrospinal fluid secondary to Chiari malformation comorbid with hypermobile EDS [22, 42, 43]. Inferior displacement of the cerebellar tonsils creates an elongated and obstructed system for cerebrospinal fluid outflow which promotes a hypertensive state in the subarachnoid space, directly affecting the optic nerve and causing IIH findings such as papilledema [44, 45]. Another hypothesis is related to the increased odds of finding carotid-cavernous fistula formation in vascular EDS patients [46, 47]. Pollack et al., reports that structural deficits in type III collagen have been associated with ophthalmic arterial wall abnormalities and concurrent fistula formation with the cavernous sinus [48]. Resulting changes to cavernous sinus pressure may act as a nidus for turbulent flow and increased pressure around the optic nerve [49].

Conversely, T2 DR, AMD, and hypertensive retinopathy were among those diagnoses with the most significantly decreased odds in overall patients diagnosed with EDS. This may be the combination of the shortened life expectancy of people with EDS (median life span of 48 years), younger mean ages of the EDS cohort in the dataset, and the delayed presentation of T2 DR, AMD, and hypertensive retinopathy leading to diagnoses at later stages of life [50,51,52]. This is further corroborated by the dramatically lower numbers of EDS diagnoses in the 61+ cohort and lack of significant PORs for the ocular conditions in this cohort (Fig. 1d). Future study pursuits could aim to include age-matching and explore the prevalence of the disease, such as diabetes, that underlies the related ocular comorbidity in EDS patients.

Another notable finding in this study was that a diagnosis of ROP had significantly decreased odds in EDS records. ROP is most often a consequence of preterm birth and pregnancies, and an EDS foetus has a higher rate of preterm birth [53,54,55]. The opposite finding in our study raises further questions about the pathogenesis of ROP with EDS that would benefit from study from a molecular perspective.

Limitations inherent to the use of the platform include lack of visibility into patient cases if the query results in patient counts between 1–10 patients. Thus, rare conditions, especially when broken into 30-year-age cohorts, could not be included in the study to preserve the accuracy of the analysis. Additionally, because the platform depends on accurate diagnoses and reliable ICD coding, the study data is likely an underestimation of true clinical cases. The platform’s general population carries an inherent bias towards those utilizing the healthcare system, as it captures anyone who has a visit recorded in the EHR. Thus, although it is not a true measure of the US population, the platform has been found to have comparable percentages of patients to the US Census with the exception of Hispanic patients [56]. Similarly, because socioeconomic factors cannot be coded for, uncontrollable confounding variables may have been introduced into the study. A limitation inherent to the study was the inability to gather nor analyse data on EDS subtypes because the platform did not contain this granularity. A final study limitation involves bypassing Bonferroni correction through the statistical analysis of multiple comparisons on the dataset. This was attempted to be addressed through the inclusion of the p values in the figures.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that an EDS diagnosis was most prevalent in white females aged 0–30 years old. Additionally, it showed that patients aged 0–60 years old who are diagnosed with EDS are at increased odds for many ocular conditions that involve collagenous structures of the eye, compared to counterparts of the same age. Specifically, diagnoses of IIH, myopia, dry eye syndrome, and carotid cavernous fistulas were among the highest odds in EDS records. Although angioid streaks demonstrated markedly increased odds in EDS records, this condition was ultimately too rare to be studied in this platform and may be better suited for targeted retrospective study. However, the frequency of ocular findings in EDS patients suggests that an ophthalmological referral may be a beneficial addition to the initial care of a newly diagnosed EDS patient. Inclusion of screenings for these conditions can also guide patient-provider conversations on the potential impacts of an EDS diagnosis on the patient’s ocular health. Future studies should examine the effects of these findings after propensity matching by potential confounders such as age, further clarify the pathogenesis of EDS ocular manifestations, or explore the associations between ocular conditions and causes of EDS morbidity, such as cardiovascular events.

Summary

What was known before:

-

Ehler-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) is a genetic disorder of collagen formation.

-

Ocular manifestations are not well characterized, with literature largely consisting of case reports or case series which report a widely varied patient presentation.

-

Collagen malformations are pervasive in the eye given the pervasiveness of ocular collagenous structures.

What this study adds:

-

Patients diagnosed with EDS are at increased odds of having a recorded diagnosis of a concurrent ocular pathology, notably idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

-

Patients diagnosed with EDS are at decreased odds for ocular diagnoses with an older age at presentation, such as diabetic retinopathy or age-related macular degeneration.

-

Ophthalmological workup, or referral to ophthalmology, should be considered in a patient diagnosed with EDS to monitor for the presence or progression of these ocular conditions

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Rachapudi SS, Laylani NA, Davila-Siliezar PA, Lee AG. Neuro-ophthalmic manifestations of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2023;34:476–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICU.0000000000001002.

Miklovic T, Sieg VC Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed April 6, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549814/

Malfait F, Castori M, Francomano CA, Giunta C, Kosho T, Byers PH. The Ehlers–Danlos syndromes. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2020;6:1–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-0194-9.

Blackburn PR, Xu Z, Tumelty KE, Zhao RW, Monis WJ, Harris KG, et al. Bi-allelic Alterations in AEBP1 Lead to Defective Collagen Assembly and Connective Tissue Structure Resulting in a Variant of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102:696–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.02.018.

Malfait F, Francomano C, Byers P, Belmont J, Berglund B, Black J, et al. The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2017;175:8–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31552.

Ritelli M, Colombi M. Molecular Genetics and Pathogenesis of Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome and Related Connective Tissue Disorders. Genes. 2020;11:547 https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11050547.

Brady AF, Demirdas S, Fournel-Gigleux S, Ghali N, Giunta C, Kapferer-Seebacher I, et al. The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, rare types. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2017;175:70–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31550.

Yeowell HN, Pinnell SR. The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Semin Dermatol. 1993;12:229–40.

Hausser I, Anton-Lamprecht I. Differential ultrastructural aberrations of collagen fibrils in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome types I-IV as a means of diagnostics and classification. Hum Genet. 1994;93:394–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00201664.

Yassin OM, Rihani FB. Multiple developmental dental anomalies and hypermobility type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2006;30:337–41. https://doi.org/10.17796/jcpd.30.4.72426m58695tg2h0.

Thwaites PA, Gibson PR, Burgell RE. Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and disorders of the gastrointestinal tract: What the gastroenterologist needs to know. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:1693–709. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.15927.

Shabani M, Abdollahi A, Brar BK, MacCarrick GL, Ambale Venkatesh B, Lima J, et al. Vascular aneurysms in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome subtypes: A systematic review. Clin Genet. 2023;103:261–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.14245.

Meester JAN, Verstraeten A, Schepers D, Alaerts M, Van Laer L, Loeys BL. Differences in manifestations of Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;6:582–94. https://doi.org/10.21037/acs.2017.11.03.

Perez-Roustit S, Nguyen DT, Xerri O, Robert MP, De Vergnes N, Mincheva Z, et al. [Ocular manifestations in Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes: Clinical study of 21 patients]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2019;42:722–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfo.2019.01.005.

Whitaker JK, Alexander P, Chau DY, Tint NL. Severe conjunctivochalasis in association with classic type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. BMC Ophthalmol. 2012;12:47. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2415-12-47.

Klaassens M, Reinstein E, Hilhorst-Hofstee Y, Schrander JJ, Malfait F, Staal H, et al. Ehlers-Danlos arthrochalasia type (VIIA-B)-expanding the phenotype: from prenatal life through adulthood. Clin Genet. 2012;82:121–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01758.x.

Ozer PA, Yalniz-Akkaya Z. Congenital keratoglobus with multiple cardiac anomalies: a case presentation and literature review. Semin Ophthalmol. 2015;30:305–12. https://doi.org/10.3109/08820538.2013.839814.

Gharbiya M, Moramarco A, Castori M, Parisi F, Celletti C, Marenco M, et al. Ocular features in joint hypermobility syndrome/ehlers-danlos syndrome hypermobility type: a clinical and in vivo confocal microscopy study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154:593–600.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2012.03.023.

Villani E, Garoli E, Bassotti A, Magnani F, Tresoldi L, Nucci P, et al. The cornea in classic type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: macro- and microstructural changes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:8062–8. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.13-12837.

Colombi M, Dordoni C, Venturini M, Ciaccio C, Morlino S, Chiarelli N, et al. Spectrum of mucocutaneous, ocular and facial features and delineation of novel presentations in 62 classical Ehlers-Danlos syndrome patients. Clin Genet. 2017;92:624–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.13052.

Louie A, Meyerle C, Francomano C, Srikumaran D, Merali F, Doyle JJ, et al. Survey of Ehlers-Danlos Patients’ ophthalmic surgery experiences. Mol Genet Genom Med. 2020;8:e1155. https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.1155.

Asanad S, Bayomi M, Brown D, Buzzard J, Lai E, Ling C, et al. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes and their manifestations in the visual system. Front Med. 2022;9:996458 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.996458.

van Dijk FS, Ghali N, Chandratheva A. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: importance of defining the type. Pr Neurol. 2024;24:90–97. https://doi.org/10.1136/pn-2023-003703.

Tinkle BT, Bird HA, Grahame R, Lavallee M, Levy HP, Sillence D. The lack of clinical distinction between the hypermobility type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and the joint hypermobility syndrome (a.k.a. hypermobility syndrome). Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:2368–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.33070.

Demmler JC, Atkinson MD, Reinhold EJ, Choy E, Lyons RA, Brophy ST. Diagnosed prevalence of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and hypermobility spectrum disorder in Wales, UK: a national electronic cohort study and case–control comparison. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e031365 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031365.

Inokuchi R, Kurata H, Endo K, Kitsuta Y, Nakajima S, Hatamochi A, et al. Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Without the Characteristic Facial Features. Med (Balt). 2014;93:e291 https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000000291.

Cortini F, Villa C, Marinelli B, Combi R, Pesatori AC, Bassotti A. Understanding the basis of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome in the era of the next-generation sequencing. Arch Dermatol Res. 2019;311:265–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-019-01894-0.

Bailey AJ. Structure, function and ageing of the collagens of the eye. Eye Lond Engl. 1987;1:175–83. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.1987.34.

Ihanamäki T, Pelliniemi LJ, Vuorio E. Collagens and collagen-related matrix components in the human and mouse eye. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2004;23:403–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.04.002.

Green WR, Friedman-Kien A, Banfield WG. Angioid streaks in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1966;76:197–204. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1966.03850010199009.

Singman EL, Doyle JJ. Angioid Streaks Are Not a Common Feature of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:239 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.5995.

Mahroo OA, Hykin PG. Confirmation That Angioid Streaks Are Not Common in Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:1463.

Asif MI, Kalra N, Sharma N, Jain N, Sharma M, Sinha R. Connective tissue disorders and eye: A review and recent updates. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023;71:2385–98. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_286_22, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.2549.

Bullimore MA, Lee SS, Schmid KL, Rozema JJ, Leveziel N, Mallen E, et al. IMI—Onset and Progression of Myopia in Young Adults. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2023;64:2 https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.64.6.2.

Yu Q, Zhou JB. Scleral remodeling in myopia development. Int J Ophthalmol. 2022;15:510–4. https://doi.org/10.18240/ijo.2022.03.21.

Kling S, Torres-Netto EA, Abdshahzadeh H, Espana EM, Hafezi F. Collagen V insufficiency in a mouse model for Ehlers Danlos-syndrome affects viscoelastic biomechanical properties explaining thin and brittle corneas. Sci Rep. 2021;11:17362. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96775-w.

Hirose T, Suzuki I, Takahashi N, Fukada T, Tangkawattana P, Takehana K. Morphometric analysis of cornea in the Slc39a13/Zip13-knockout mice. J Vet Med Sci. 2018;80:814–8. https://doi.org/10.1292/jvms.18-0019.

Segev F, Héon E, Cole WG, Wenstrup RJ, Young F, Slomovic AR, et al. Structural abnormalities of the cornea and lid resulting from collagen V mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:565–73. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.05-0771.

Swierkowska J, Gajecka M. Genetic factors influencing the reduction of central corneal thickness in disorders affecting the eye. Ophthalmic Genet. 2017;38:501–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/13816810.2017.1313993.

Burkitt Wright EM, Porter LF, Spencer HL, Clayton-Smith J, Au L, Munier FL, et al. Brittle cornea syndrome: recognition, molecular diagnosis and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:68. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-8-68.

Baratta RO, Schlumpf E, Buono BJD, DeLorey S, Calkins DJ. Corneal collagen as a potential therapeutic target in dry eye disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2022;67:60–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2021.04.006.

Henderson FC Sr, Austin C, Benzel E, Bolognese P, Ellenbogen R, Francomano CA, et al. Neurological and spinal manifestations of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2017;175:195–211. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31549.

Ellington M, Francomano CA. Chiari I Malformations and the Heritable Disorders of Connective Tissue. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2023;34:61–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nec.2022.09.001.

Pinna G, Alessandrini F, Alfieri A, Rossi M, Bricolo A. Cerebrospinal fluid flow dynamics study in Chiari I malformation: implications for syrinx formation. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;8:E3 https://doi.org/10.3171/foc.2000.8.3.3.

Vandenbulcke S, Condron P, Safaei S, Holdsworth S, Degroote J, Segers P. A computational fluid dynamics study to assess the impact of coughing on cerebrospinal fluid dynamics in Chiari type 1 malformation. Sci Rep. 2024;14:12717. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62374-8.

Linfante I, Lin E, Knott E, Katzen B, Dabus G. Endovascular repair of direct carotid-cavernous fistula in Ehlers-Danlos type IV. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2013010990 https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-010990.

Adham S, Trystram D, Albuisson J, Domigo V, Legrand A, Jeunemaitre X, et al. Pathophysiology of carotid-cavernous fistulas in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a retrospective cohort and comprehensive review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13:100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-018-0842-2.

Pollack JS, Custer PL, Hart WM, Smith ME, Fitzpatrick MM. Ocular complications in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Arch Ophthalmol Chic Ill 1960. 1997;115:416–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150418018.

Chaudhry IA, Elkhamry SM, Al-Rashed W, Bosley TM. Carotid cavernous fistula: ophthalmological implications. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2009;16:57–63. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-9233.53862.

Yin L, Zhang D, Ren Q, Su X, Sun Z. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetic retinopathy in diabetic patients: A community based cross-sectional study. Med (Balt). 2020;99:e19236 https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000019236.

Thomas CJ, Mirza RG, Gill MK. Age-related macular degeneration. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105:473–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2021.01.003.

Cheung CY, Biousse V, Keane PA, Schiffrin EL, Wong TY. Hypertensive eye disease. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2022;8:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-022-00342-0.

Dammann O, Hartnett ME, Stahl A. Retinopathy of prematurity. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2023;65:625–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.15468.

Underhill LA, Barbarita C, Collis S, Tucker R, Lechner BE. Association of maternal versus fetal Ehlers-Danlos syndrome status with poor pregnancy outcomes. Reprod Sci. 2022;29:3459–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-022-00992-1.

Alrifai N, Alhuneafat L, Jabri A, Khalid MU, Tieliwaerdi X, Sukhon F, et al. Pregnancy and fetal outcomes in patients with ehlers-danlos syndrome: a nationally representative analysis. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023;48:101634 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2023.101634.

Markle J, Shaia JK, Araich H, Sharma N, Talcott KE, Singh RP. Longitudinal trends and disparities in diabetic retinopathy within an aggregate health care network. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024;142:599–606. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2024.0046.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) grant, UL1TR002548, P30EY025585(BA-A),/ Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB) Challenge Grant, Cleveland Eye Bank Foundation Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SBK contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing, and manuscript revisions. JS contributed to study design, data analysis, and manuscript revisions. DK, RS, KT contributed to study design and manuscript revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

DK reports personal fees from Dynavax Technologies Corporation. RS reports personal fees from Apellis, Iveric Bio, Eyepoint, Regenxbio, Genentech, Bausch and Lomb, Zeiss, Alcon, and Regeneron, and research grants from Janssen. KT reports personal fees from Alimera, Abbvie, Apellis, Astellas, Eyepoint, Genentech, Outlook, Regeneron, and Zeiss, and research fees from Regeneron and Zeiss.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S.B., Shaia, J.K., Kaelber, D.C. et al. Ocular manifestations in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Eye 39, 1990–1997 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-025-03787-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-025-03787-1

This article is cited by

-

„Angioide Streifen“ als mögliches Zeichen einer systemischen Grunderkrankung

Die Ophthalmologie (2026)