Abstract

Little information is available about CCR5-Δ32 and HLA-B*57:01 alleles in the Peruvian population, especially in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative people with high-risk sexual behavior. Here we describe the prevalence of these alleles in HIV-exposed seronegative individuals (PS) and HIV-seropositive individuals (PVV). For this purpose, 300 individuals were recruited: 150 from each group, and the selected alleles were characterized by endpoint PCR, real-time PCR and DNA sequencing. According to our results, the prevalence of CCR5/CCR5-Δ32 heterozygous was 2.7%, and no homozygous cases were found. The population was in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for the CCR5 locus. Regarding HLA-B*57:01, one case was identified in the PS group, while no cases were observed in the PVV group. No statistical difference was detected between groups (P > 0.05). In conclusion, we showed a low prevalence for CCR5-Δ32 as HLA-B*57:01 in the Peruvian population. As these alleles were found at similar frequencies among both HIV-positive and HIV-negative Peruvian individuals with high-risk sexual behavior, it is possible that other genetic factors play an important role in preventing HIV transmission in this population. The low frequency of the HLA-B*57:01 allele in the Peruvian population suggests that routine genotyping tests for abacavir hypersensitivity should be reevaluated in the public health policies of Peru’s Ministry of Health, based on national epidemiological data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Genetic factors have been implicated in resistance to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection despite multiple high-risk exposures, as well as in differing rates of progression to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) among infected individuals1. Genes such as CCR5 Δ32 and HLA-B*57:01 have been implicated in viral entry and immune response processes, respectively2. In the first case, a 32-bp deletion in the CCR5 gene is sufficient to interfere with, and in some cases prevent, viral entry into the cell—particularly in individuals who are homozygous for the mutation1. The HLA-B*57:01 allele is associated not only with slow progression to AIDS3 but also with genetic susceptibility to the antiretroviral drug abacavir (ABC) hypersensitivity reaction (ABC-HSR)4, which is known to cause severe clinical manifestations5. For this reason, HLA-B*57:01 genotyping is recommended before prescribing the drug6. In Peru, the Ministry of Health has developed the technical standard NTS N°169-MINSA/2020/DGIESP7, which establishes the requirement to perform the HLA-B*57:01 genotyping test before administering ABC. However, this political decision was made without having proven that HLA-B*57:01 frequency in the Peruvian population.

In contrast to Europe, the prevalence of both CCR5-Δ32 and HLA-B*57:01 is low in African, Asian and Latin American populations8. In Peru, this mutation may have been introduced into the local population by gene flow through admixture with the European population9,10. This is supported by few reports found in some Peruvian individuals8,11. However, none of these studies included the geographic origin of the recruited participants, which complicates interpretation, as the Peruvian population comprises communities with varying degrees of ethnic admixture and, consequently, genetic variability12. Moreover, in the context of HIV/AIDS disease, none of these studies included clinical or socioepidemiological data that could help clarify the relevance of these alleles in the evolution of the epidemic in Peru.

For this study, we recruited Peruvian individuals and collected data on their geographic origin as well as social, epidemiological, and clinical characteristics to better understand how the genetic makeup of the Peruvian population relates to the HIV/AIDS epidemic

Materials and methods

Type and design of study

This observational cross-sectional study was performed between December 2020 and November 2021.

Population and sample size

The study population consisted of Peruvian individuals treated at the Asociación Civil Voluntades Lima Norte Non-Governmental Organization and the Santa Rosa Hospital. This population was divided into two groups: (1) HIV-exposed seronegative individuals (PS) and (2) HIV-seropositive individuals (PVV). The geographic origin of the participants was predominantly Lima (71%), a city characterized by a highly admixed population and the greatest genetic diversity in the country12. From this population, the sample size was calculated using the proportion formula for finite population based on (1) an expected prevalence of 1% for HLA-B*57:01 and CCR5-Δ32 in a mixed population (mainly with native ancestry), (2) a population of 800 individuals, (3) a confidence level of 95% and (4) an error margin of 1%. The minimum number of participants required to estimate the prevalence of CCR5-Δ32 and HLAB-57:01 alleles was 258; however, in this study a sample size of 300 individuals was used to increase the power and precision of the results. The selection criteria were the following: (1) Peruvian nationality, (2) legal age (18 years or more), (3) both sexes (male and females) and (4) agreement to participate in the study by signing an informed consent and completing a survey using a data collection instrument. Furthermore, for the PVV group, HIV seropositivity was confirmed through diagnostic tests, whereas for the PS group, seronegativity was confirmed by both third- and fourth-generation rapid tests, along with documented high-risk sexual behaviors such as occasional contact with sex workers, intermittent condom use and multiple sexual partners.

CCR5 genotyping

DNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin kit (Macherey-Nagel), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. CCR5 genotyping was based on endpoint polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay using primers flanking the 32-bp deletion, CCR5 DELTA1 (5′-ACCAGATCTCTCAAAAAGAAGGTCT-3′) and CCR5 DELTA2 (5′-CATGATGGTGAAGATAAGCCTCCACA-3′)2. The reaction included 0.2 µM of each primer, 0.04 U of Velocity DNA polymerase enzyme, 2.5 mM Mg2+ and 0.6 mM dNTP mixture in a final volume of 25 µl. The cycling parameters were: 1 cycle 98 °C × 30 s; 35 cycles 98 °C × 30 s, 60 °C × 30 s, 72 °C × 15 s; 1 cycle of 72 °C × 3 min. The amplified products were visualized by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis. For the CCR5/CCR5 genotype, a single band of 225 bp is expected; for the CCR5/Δ32 genotype, bands of 225 bp and 193 bp; and for the CCR5-Δ32/ CCR5-Δ32 genotype, a single band of 193 bp.

HLA-B*57:01 allele genotyping

HLA-B*57:01 genotyping was performed using a modified procedure based on Jung et al.13. The PCR reaction included 10–60 ng/μl of genomic DNA, 1× Kapa Probe Fast Master Mix (Roche), 0.3 μmol/l of each primer (B5071-T1F: AGGGTCTCACATCATCCAGGT and B5701-T3R: CGTTCAGGGCGATGTAATCCT) and 0.2 μmol/l of each probe (B5701-P2: 6FAM-CGCGGGCATGACCAGTC-MGBNFQ), with a final volume of 10 μl. The amplification program had the following parameters: 95 °C for 5 min; and 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 68 °C for 30 s. Molecular-grade water was used as a negative control, and a previously genotyped HLA-B*57:01 (+) sample (confirmed by a commercial kit) served as the positive control. Samples with a Ct value <30 for both HLA-B*57:01 and the internal control (alpha-actine 1) were considered as positive for the HLA-B*57:01 allele.

Sanger sequencing

DNA samples whose PCR product revealed the presence of heterozygous genotype for CCR5-Δ32 were purified from gel. The primers described by Diaz et al. were used2. In the case of HLA-B*57:01, the amplification products were directly purified using magnetic beads and primers described by Jung et al.13. In both cases, Big Dye Terminator reagent was used, and the products were settled on the Applied Biosystems 3500 XL genetic analyzer. In the case of CCR5, both forward and reverse sequences were edited and assembled with the software SeqTrace v.0.9.0, whereas, for HLA-57:01, we used the free-access program SoapTyping V1.0.6.3. The resulting electropherograms were aligned and compared with the sequence deposited in GenBank (accession code LR961919, information detailed in the link:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/LR961919).

Statistical analysis

Comparison of categorical and quantitative variables was performed with the chi-square test or Fisher’s test (f < 5), and the Mann–Whitney test, respectively. Deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium were calculated using the chi-square test. Frequencies of each allele were compared between HIV-exposed seronegative and HIV-seropositive individuals, using chi-square test or Fisher’s test when appropriate. In all analyses, P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Finally, a new sample statistical power calculation was performed using the actual allele frequencies observed. For this, the power of a two-sided Fisher’s exact test (exact2x2) was calculated using RStudio v4.1.2. The calculation assumed that CCR5Δ32 confers resistance, with the alternative hypothesis set to a one-sided test within the same function call.

Results

The data of the 300 participants are summarized in Table 1. For the PVV groups, the mean age was 36 years (83.3% males and 16.7% females), while for the PS group, the mean age was 33 years (84.7% males and 15.3% females). Most of the participants in either the PVV or the PS came from Lima (64%), followed by Lambayeque (6%) for the PVV, Ica for the PVV and PS (4% each) and La Libertad and Loreto for the PVV and PS (3% each). Regarding risk behavior, no information was available for the PVV group; however, in the PS group, 36% reported homosexual orientation (men who have sex with men (MSM) and Trans H-M), 10.7% bisexual, and 53.3% heterosexual. Both groups showed statistically significant differences in chronological age (P = 0.02) and immunological status (P < 0.01), indicating immunological failure in PVV.

The CCR5/CCR5 genotype was observed as a single band of 225 bp, whereas the CCR5/CCR5-Δ32 genotype was visualized as two bands (225 and 193 bp) (Fig. 1). No CCR5-Δ32/CCR5-Δ32 genotype were detected in the 300 samples. The mutated allele (CCR5-Δ32) was further confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 2).

We found that the prevalence of CCR5 Δ32 heterozygotes was 2.7%, while the frequency of the allele was 1.3% (Table 2). No homozygotes were found for the mutated allele. In the PVV group, 2% had the heterozygous genotype and the frequency of the CCR5-Δ32 allele was 1%. In the PS group, 3.3% had the heterozygous genotype and the frequency of the CCR5-Δ32 allele was 1.7%. The distribution of genotype and allele frequencies between the two groups was not statistically significantly different (P > 0.05). To determine if the lack of statistical significance was due to insufficient statistical power, we recalculated the statistical power of Fisher’s exact test as described in the ‘Materials and methods’ section. Considering a one-sided test (alternative = ‘one.sided’), the power was determined to be 0.091, requiring a total of 3304 per group to achieve a statistical power of 80%.

Meanwhile, Hardy–Weinberg analysis showed that the CCR5-Δ32 allele was in equilibrium within each group and across the total population (>0.05) (Table 2).

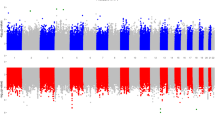

Real-Time PCR results showed Ct values below 30 for both the HLA-B57:01 allele and the internal control in 5 of the 300 analyzed samples. However, only one of these samples (PS134) showed a fluorescence level comparable to the positive control (Fig. 3a); hence, Sanger sequencing was used to avoid false positives.

a Real-time PCR results. The sample PS134 is the only one with a similar fluorescence level as the positive control (C+). b Comparison of nucleotides according to electropherogram peaks with the HLA-B*57:01:01 sequence extracted from GenBank. The red rectangle indicates the position of the SNP (C/T) for HLA-B*57:01:01.

Analysis using the SoapTyping program revealed matches to the HLA-B57:01 allele in only one of the five samples (data not shown). Based on the electropherograms, we confirmed that this sample had polymorphisms compatible with the sequence of the HLA-B*57:01:01 allele stored in the GenBank platform (accession number LR961919), whereas the remaining four samples had noncompatible polymorphisms in the region complementary to the 3′ end of the probe (Fig. 3b). Therefore, we consider that sample PS134 carries the HLA-B*57:01 (+) genotype.

Overall, the prevalence of the HLA-B*57:01 genotype was 0.33%. In the PS group, the prevalence was 0.67%. No HLA-B*57:01 genotype was identified among HIV-seropositive individuals (PVV). The prevalence between the two groups was not statistically significantly different (P > 0.05) (Table 3). Similarly to CCR5-Δ32, we performed a new calculation of the statistical power of the sample based on the identified HLA-B*57:01 frequency value. According to our results, the statistical power was 0.003507617, indicating that a sample size greater than 50,000 would be required.

Discussion

In the present study, we have described the CCR5-Δ32 and HLA-B*57:01 alleles in HIV-exposed seronegative and HIV-1 seropositive Peruvian individuals and collected social, clinical and epidemiological information for each participant. In the case of CCR5-Δ32, our findings reveal that the prevalence of this mutation was low, which could be related to the low degree of admixture detected between the current Peruvian population and the European population, primarily Spanish10. The sample of Peruvian individuals analyzed in this study did not present any homozygous case for the CCR5 mutation, consistent with the results from previous studies in Latin American countries8,14,15.

In contrast to our data, Solloch et al.8 reported a higher prevalence for CCR5-Δ32 (5% versus 3%). This difference, albeit small, could be related to the methodology used, the size of the sample and the selection of the population. In addition, Solloch et al.8 did not provide further information on the individuals’ backgrounds, making it difficult to assess how the degree of admixture among Peruvians varies by geographical origin. In our study, we included participants from 18 cities in Peru, primarily from Lima, Lambayeque and Loreto—regions known for having the highest genetic variability in the country12. These data suggest that the selected populations might be representative of Peru; however, further nationwide studies are needed to confirm this.

Regarding the HLA-B*5701 allele, our study showed a lower frequency than CCR5-Δ32, which could be due to its higher distribution in Caucasian populations than in Latin American or Native American populations16,17. The allele frequency in some Latin American countries ranged from 1% to 5.6% (refs.16,17,18,19), suggesting that the degree of admixtures with the European lineage is variable. Martínez et al.17, who reported a prevalence of 2.7% among HIV-infected Colombians, found that, when the sample was stratified according to ethnic characteristics, the prevalence was higher in white individuals (4%) than in other ethnic groups such as mestizos (2.6%) or Afro-Colombians (1.9%). These results show that the allele distribution in Latin America may differ depending on the local ethnic characteristics of each country, suggesting that the degree of admixture in this population is higher than in other regions of the world.

On this last point, the study published by Vilcarino et al.11 found a frequency of 4% in a sample of 49 Peruvian participants. However, the data on the geographical origin of these samples are limited, as most of them included only individuals from the same city. In addition, the sample size was very small, so this value could not be considered representative of the Peruvian population. By contrast, the sample size in this study was larger (n = 300) and from different regions of Peru (Table 1). Considering that the Allele Frequency Net database (https://www.allelefrequencies.net/) lacks data on the prevalence of this allele in Peru, this study may be the first to provide approximate prevalence estimates of HLA-B*57:01 in the Peruvian population.

From a clinical point of view, the presence of both CCR5-Δ32 and HLA-B*57:01 have been associated with slow progression to AIDS in carrier individuals1,3. Their presence in the Peruvian population opens the possibilities of finding a specific group of individuals with slow progression to AIDS. However, among carriers of the CCR5-Δ32 mutation, only one exhibited a viral load below 20 copies, while the others had viral loads exceeding 1000 copies. It is therefore possible that pharmacological and/or genetic factors may influence virological failure in carriers of this mutation.

The CD4 count was statistically significantly lower in PVV, which is to be expected because HIV infection is associated with a depletion of the CD4 lymphocyte population20. However, when analyzing the immune response status of CCR5-Δ32 mutation carriers in the PVV group (PVVCCR5/Δ32, n = 3), they showed more than 400 CD4+ cells/µl, a value outside the threshold for risk of developing AIDS21, and above the average CD4 of those who did not carry this mutation. The high proportion of CD4+ cells may be a consequence of CD30L overexpression associated with the 32-nucleotide deletion22. Another important detail related to the immune response is that the antiretroviral treatment currently being received by PVVCCR5/Δ32 based on a combination of dolutegravir, tenofovir, lamivudine and efavirenz may also contribute to favoring the immune response against HIV, as has been described in a previous study23. However, ex vivo experiments have shown that treatment with dolutegravir has the opposite effect, generating a decrease in the CD4 population24. Considering that two individuals in the PVVCCR5/Δ32 group were treated with this drug and still maintained a CD4 count greater than 400 cells/µl, we suggest that the CD4 population restoration is attributable to the mutation.

We collected the data regarding the risk behavior of CCR5-Δ32 mutation carriers from the PS group (PSCCR5/Δ32, n = 5). They reported high-risk sexual behavior for HIV/Sexual Transmitted Infections such as multiple sexual partners, infection by sexual transmission, use of recreational drugs and intermittent condom use. In spite of this, they had a good immune response (an average of 1,011.4 cells/µl) and a negative diagnosis of HIV at quarterly or half-yearly monitoring tests. These characteristics may be associated with the CCR5-Δ32 mutation, which, according to this study, was more prevalent in PS than in PVV, although not statistically significantly so. Because the statistical power calculation yielded a value of 0.091, this finding suggests a possible false negative due to the small sample size (n = 300) in this study. However, the possibility of other genetic or immunological factors contributing to a degree of resistance to PS should not be discounted. In fact, a recent exome study revealed a new allele HLA-DQB1*03:419 found in the Peruvian population associated with immunological protection (P < 0.04)25. These findings highlight the need for further genomic research to identify new protective genes in different geographic regions of Peru.

The presence of a single individual with the HLA-B*57:01 allele among 300 HIV-positive and HIV-negative Peruvian individuals (0.3%) indicates the rarity of this allele in the Peruvian population. This fact may be related to the population’s predominantly indigenous genetic characteristics, even among the mestizo population, as demonstrated in previous studies12,26. Considering the approximate HIV prevalence in the Peruvian population is 0.3% and that 89% of those diagnosed have access to antiretroviral therapy27, the administration of ABC in this group would be exceptional. In fact, only 6 of the 150 HIV-positive participants in our study received ABC, confirming the limited access to this drug. Moreover, the Peruvian Technical Normative on Antiretroviral Therapy Recommendations does not mandate the use of this drug in first- or second-line therapy, which could explain why Peruvian doctors prescribe it as a second alternative, among other clinical reasons.

Regarding the administration of ABC, cohorts including more than 200,000 participants, mostly Caucasian, revealed that only 5–8% of cases presented hypersensitivity symptoms when treated with ABC28. Likewise, only 6% of those with the mutation who manifested hypersensitivity reactions are at high risk29.

Regarding the financial sustainability of the HLA-B*5701 test, it has been shown to be cost-effective in a US population30; however, these estimates could vary in populations with high levels of interbreeding, such as the Peruvian population. In fact, a significant proportion of the Peruvian population is of indigenous descent, even among the mestizo population12. Together, these data suggest reconsidering the value of routinely detecting this allele within Peru’s resistance surveillance and monitoring system, unless multicenter studies with representative sample sizes are conducted to define its national distribution. Given that our results indicate that achieving 80% statistical power requires recruiting over 50,000 participants, the cost-effectiveness of HLA-B*5701 testing for routine use could be disregarded. Based on the evidence from this study and current ABC management practices in Peru, it is possible that hypersensitivity cases in this country are very rare. However, these findings should be viewed with caution.

Finally, this study focuses on the genetic variants CCR5-Δ32 and HLA-B*57:01 in PVV and PS groups, and the results presented will support future studies in estimating more representative sample sizes across different geographical regions of Peru. It also demonstrates the need for local studies in search of markers to better understand HIV resistance in at-risk populations and to predict the prognosis of AIDS in the Peruvian population. The effects of CCR5-Δ32 in Peruvian individuals may differ from those described in European populations, due to genetic heterogeneity. These effects are influenced not only by allele frequency but also by interactions with other genes that may modulate CCR5-Δ32 expression individually or synergistically31.

In conclusion, our findings show that the prevalence of both CCR5-Δ32 and HLA-B*57:01 alleles is low, supporting evidence of limited recent gene flow between European populations and indigenous communities in present-day Peru. Similarly, the presence of one carrier of the HLA-B*57:01 allele—and two previously reported cases—demonstrates the ongoing surveillance of ABC hypersensitivity in the Peruvian population. However, further nationwide investigations covering each region of Peru are needed to obtain a truly representative sample of the Peruvian population.

References

An, P. & Winkler, C. A. Host genes associated with HIV/AIDS: advances in gene discovery. Trends Genet. 26, 119–131 (2010).

Langford, S. E., Ananworanich, J. & Cooper, D. A. Predictors of disease progression in HIV infection: a review. AIDS Res. Ther. 4, 11 (2007).

UK Collaborative HIV Cohort Study Steering Committee. HLA B*5701 status, disease progression, and response to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 27, 2587–2592 (2013).

Mallal, S. et al. Association between presence of HLA-B*5701, HLA-DR7, and HLA-DQ3 and hypersensitivity to HIV-1 reverse-transcriptase inhibitor abacavir. Lancet 359, 727–732 (2002).

Quiros-Roldan, E. et al. Abacavir adverse reactions related with HLA-B*57: 01 haplotype in a large cohort of patients infected with HIV. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 30, 167–174 (2020).

Mallal, S. et al. PREDICT-1 Study Team. HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 568–579 (2008).

Norma Técnica de Salud de Atención Integral del Adulto con Infección por el Virus de la Inmunodeficiencia Humana (VIH) Resolución Ministerial N.° 1024-2020-MINSA (Ministerio de Salud, 2020); https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/normas-legales/1422592-1024-2020-minsa.

Solloch, U. V. et al. Frequencies of gene variant CCR5-Δ32 in 87 countries based on next-generation sequencing of 1.3 million individuals sampled from 3 national DKMS donor centers. Hum. Immunol. 78, 710–717 (2017).

Homburger, J. R. et al. Genomic insights into the ancestry and demographic history of South America. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005602 (2015).

Ruiz-Linares, A. et al. Admixture in Latin America: geographic structure, phenotypic diversity and self-perception of ancestry based on 7,342 individuals. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004572 (2014).

Vilcarino-Zevallos, G. et al. Identification of the allele HLA B*57:01 in a military population, from Lima-Peru. Rev. Chilena Infectol. 41, 311–315 (2024).

Harris, D. N. et al. Evolutionary genomic dynamics of Peruvians before, during, and after the Inca Empire. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E6526–E6535 (2018).

Jung, H. S., Tsongalis, G. J. & Lefferts, J. A. Development of HLA-B*57:01 genotyping real-time PCR with optimized hydrolysis probe design. J. Mol. Diagn. 19, 742–754 (2017).

Leboute, A. P., de Carvalho, M. W. & Simões, A. L. Absence of the Δccr5 mutation in indigenous populations of the Brazilian Amazon. Hum. Genet. 105, 442–443 (1999).

Boldt, A. B. W. et al. Analysis of the CCR5 gene coding region diversity in five South American populations reveals two new non-synonymous alleles in Amerindians and high CCR5*D32 frequency in Euro-Brazilians. Genet. Mol. Biol. 32, 12–19 (2009).

Arrizabalaga, J. et al. Prevalence of HLA-B*5701 in HIV-infected patients in Spain (results of the EPI study). HIV Clin. Trials 10, 48–51 (2009).

Martínez Buitrago, E. et al. HLA-B*57:01 allele prevalence in treatment-Naïve HIV-infected patients from Colombia. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 793 (2019).

Moragas, M. et al. Prevalence of HLA-B*57:01 allele in Argentinean HIV-1 infected patients. Tissue Antigens 86, 28–31 (2015).

Poggi, H. et al. HLA-B*5701 frequency in Chilean HIV-infected patients and in general population. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 14, 510–512 (2010).

Zhao, J. et al. Infection and depletion of CD4+ group-1 innate lymphoid cells by HIV-1 via type-I interferon pathway. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1006819 (2018).

Noda, A., Vidal, L., Pérez, J. & Cañete, R. Interpretación clínica del conteo de linfocitos T CD4 positivos en la infección por VIH. Rev. Cubana Med. 52, 118–127 (2024).

Hütter, G. et al. The effect of the CCR5-Δ32 deletion on global gene expression considering immune response and inflammation. J. Inflamm. 8, 29 (2011).

Corbeau, P. & Reynes, J. Immune reconstitution under antiretroviral therapy: the new challenge in HIV-1 infection. Blood 117, 5582–5590 (2011).

Korencak, M. et al. Effect of HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy on immune cellular functions. JCI Insight 4, e126675 (2019).

Obispo, D. et al. New associations with the HIV predisposing and protective alleles of the human leukocyte antigen system in a Peruvian population. Viruses 30, 1708 (2024).

Borda, V. et al. Genetics of Latin American Diversity Project: insights into population genetics and association studies in admixed groups in the Americas. Cell Genom. 4, 100692 (2024).

Reyes, N. et al. HIV treatment cascade in regions of Peru with the highest HIV prevalence. HIV Med. 24, 620–627 (2023).

Gilani, B. & Zubair, M. HLA-B*57:01 Testing (StatPearls Publishing, 2025).

Mallal, S. et al. HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 568–579 (2008).

Schackman, B. R. et al. The cost-effectiveness of HLA-B*5701 genetic screening to guide initial antiretroviral therapy for HIV. AIDS 22, 2025–2033 (2008).

Kulmann-Leal, B., Ellwanger, J. H. & Chies, J. A. B. CCR5Δ32 in Brazil: impacts of a European genetic variant on a highly admixed population. Front. Immunol. 12, 758358 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Sánchez and L. Castro (NGO MCC Voluntades Lima Norte) for their valuable efforts and support in the recruitment process of participants and collection data through the surveys. We also thank D. Suárez-Agüero, biologist and researcher, for collaborating with us on the statistical analysis.

Author contributons

R.F.A., C.A.Y., O.A.C., S.E.A. and E.M.Z. were involved in the study conception. S.M.E.-C. and C.A.Y. were involved in the analysis of the data as well as the redaction of the manuscript. S.M.E.-C., S.E.A., D.O.-A. and M.I.D. were involved in data collection. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Peruvian entity CONCYTEC through the Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Cientifico y Tecnologico (FONDECYT) with contract number 012-2019-FONDECYT, and by the Universidad de San Martín de Porres (USMP-Peru) through projects E10012019028 and E10012023005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The procotol of the present study was previously approbed by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the Instituto Nacional de Salud code number OT-023-20).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Echavarria-Correa, S.M., Obispo-Achallma, D., Espetia Anco, S. et al. Distribution of CCR5-Δ32 and HLA-B*57:01 alleles in HIV-seropositive and HIV-exposed seronegative Peruvian individuals. Hum Genome Var 12, 15 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41439-025-00321-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41439-025-00321-3