Abstract

Array-based comparative genomic hybridization for a boy, his mother and his half-sister with etiology-unknown nonsyndromic short stature identified a hitherto unreported heterozygous ~1.5-Mb deletion at 16q24.2–q24.3. Whole-exome sequencing detected no pathogenic variants. Our results, in conjunction with previous reports of cases with similar deletions, indicate that the 16q24.2–q24.3 region provides a platform for submicroscopic deletions and possibly contains a gene(s) or regulatory elements involved in skeletal growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Nonsyndromic short stature is a relatively common disorder caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors1. Loss-of-function variants in ACAN, SHOX, NPR2 and some other genes have been implicated in nonsyndromic short stature2,3. However, these monogenic mutations explain less than 20% of cases4,5, indicating that other genetic factors play important roles in the development of this disorder. In this context, submicroscopic chromosomal deletions have been identified in several patients with nonsyndromic short stature, although these abnormalities are more commonly associated with syndromic short stature6,7,8,9.

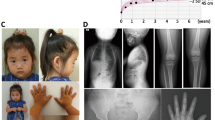

Here, we report three individuals from the same family who presented with nonsyndromic short stature and carried a submicroscopic deletion at 16q24.2–q24.3. The proband (Fig. 1A, II-5) was a 1-year-old Japanese boy. He was born at 36 weeks and 3 days of gestation with normal birth length and weight of 48.0 cm (+0.64 s.d.) and 2,474 g (−0.41 s.d.), respectively. At 1 year of age, he was referred to our hospital for the evaluation of short stature. He manifested short stature (69.1 cm, −2.27 s.d.), with normal weight (9.5 kg, +0.12 s.d.). No dysmorphic features or congenital anomalies were noted on physical examination. Laboratory tests revealed age-appropriate levels of thyroid hormones, gonadotropins and sex hormones. His insulin-like growth factor 1 level was within the normal range (21 ng/ml, −1.09 s.d.). A whole-body skeletal X-ray survey showed no remarkable findings, excluding skeletal dysplasia (Fig. 1B). He was diagnosed with nonsyndromic short stature and was followed up without medical intervention. Subsequently, his height increased along the −2.0 or −2.5 s.d. growth curves for Japanese boys (Fig. 1C). His developmental milestones were almost age-appropriate, although he was noted to have slightly delayed speech at 2 years and 8 months. During the follow-up period, he showed no clinical abnormalities except for recurrent otitis media. His mother (I-3) showed severe short stature of 130 cm (−5.36 s.d.) and spina bifida. Detailed clinical records of this individual were unavailable. A half-sister of the proband (II-1) also showed severe short stature (135 cm, −4.40 s.d.). She also had ventricular septal defect (VSD). Allegedly, a growth hormone provocation test during her childhood yielded normal results. No additional clinical features, such as intellectual disability or dysmorphic facial appearance, were noted in the mother or the half-sister. The other members of this family were phenotypically normal, except for a brother of the proband (II-4) who had mild short stature (−2.61 s.d.). Clinical information about the brother was unavailable.

Genomic DNA samples were extracted from peripheral leukocytes of the proband (II-5), the mother (I-3) and the half-sister (II-1). Samples of other family members were unavailable for genetic analysis. First, we conducted whole-exome sequencing as described previously10. The results showed no nucleotide changes that could explain the short stature of the three individuals. Then, we performed comparative genomic hybridization using a catalog array (Sure Print G3, 4 × 180K format, Agilent Technologies). As a result, we identified a heterozygous deletion in the 16q24.2–q24.3 region in the three patients. The deletion was ~1.5 Mb in size (maximum, Chr16: 87,800,426–89,304,429; minimum, Chr16: 87,800,485–89,304,370; GRCh37/hg19) and encompassed 23 protein-coding genes (Fig. 2). The deletion was not registered in the Database of Genomic Variants (https://dgv.tcag.ca/dgv/app/home) or gnomAD (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/). Fourteen of the 23 affected genes have been linked to human disorders (Supplementary Table 1). In particular, CDT1, GALNS and PIEZO1 were reported to cause syndromic short stature in an autosomal recessive manner (Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, genetic knockout of Znf469 and Trappc2l was associated with decreased body length in mice (International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium; https://www.mousephenotype.org/). However, none of these genes is known to cause autosomal dominant short stature in humans. In addition, ANKRD11, a causative gene for autosomal dominant KBG syndrome characterized by short stature, recurrent otitis, epilepsy, heart anomalies and skeletal anomalies11,12, was located at a position ~29 kb from the deletion. However, Hi-C and Micro-C data of H1 human embryonic stem cells in the UCSC Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/) suggested no close interaction between the deleted region and ANKRD11 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

A Array-based comparative genomic hybridization for the 16q11.2–q24.3 region in our cases. Green dots depict the copy-number loss region (log2 ratio of <−0.9), while black dots denote copy-number neutral regions. The genomic positions are based on GRCh37/hg19. The positions of protein-coding genes are shown. B Deletions in the present and known cases. Cases 1–13 were reported previously6,7,8,9. Blue and yellow lines indicate the deletions of individuals with and without short stature, respectively. Gray lines depict the deletions of individuals whose height data were unavailable.

Next, we consulted previous reports of deletions at 16q24.2–q24.3. Thus far, submicroscopic deletions in this region have been identified in 13 cases6,7,8,9 (Fig. 2B). The sizes of the deletions ranged from 690 kb to ~2.30 Mb. Most of the 13 patients exhibited dysmorphic features and intellectual disability with some additional clinical symptoms (Supplementary Table 2). VSD and multiple skeletal anomalies were observed in one case each (cases 7 and 12, respectively). Three of the 13 patients (cases 1–3) were reported to have short stature, while 3 had normal stature (cases 4–6), and height data were unavailable for the remaining 7 cases. We observed no apparent genotype–phenotype correlation in the 13 cases, except for the relatively severe phenotype in case 12 with a large deletion.

This study provided two notable findings. First, our data, in conjunction with prior observations6,7,8,9, imply that the ~2-Mb genomic interval at 16q24.2–q24.3 represents a platform for submicroscopic deletions. Because the present and previous deletions had different breakpoints (Fig. 2B), these abnormalities are more likely to arise from replication-based errors or nonhomologous end joining than non-allelic homologous recombination13. The genomic interval at 16q24.2–q24.3 may contain elements that facilitate de novo deletion, because it is known that de novo copy-number variants in the human genome tend to be clustered in regions with specific chromosomal architectural features14. Notably, the deleted interval harbors several genes implicated in congenital malformations or intellectual disability (Supplementary Table 1). Consistent with this, previously reported 13 cases manifested intellectual disability with additional clinical features (Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, VSD of our patient (II-1) and case 7 can be ascribed to the haploinsufficiency of ZFPM1 and/or ZNF7789. While the proband of this study exhibited no apparent congenital malformations or intellectual disability, this can be explained by the broad phenotypic variations in patients with heterozygous submicroscopic deletions6,7,8,9. Second, in the present family, the etiological relationship between the ~1.5-Mb deletion and nonsyndromic short stature remains uncertain. Because we could not obtain genomic DNA samples from three siblings of the proband, it was impossible to confirm the segregation between the deletion and short stature in this family. However, the deletion was the sole genetic abnormality identified in the three patients by whole-exome sequencing and array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Considering that at least 3 of the 13 known cases (cases 1–3) exhibited short stature (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2), this region probably contains a gene(s) involved in skeletal growth. In this regard, the functionally uncharacterized genes BANP and ZC3H18 may play important roles in human health, because these genes are ubiquitously expressed and have high probability of loss-of-function intolerance (pLI) scores indicative of functional importance (Supplementary Table 1). Alternatively, the short stature in our cases may result from dysregulation of a nearby gene. Although Hi-C and Micro-C data suggested no close interaction between the deleted region and ANKRD11, we cannot exclude the possibility that the deletion encompasses a distal enhancer of ANKRD11. Further studies are necessary to clarify the etiological relationship between 16q24.2–q24.3 deletions and short stature.

In summary, we identified a hitherto unreported ~1.5-Mb deletion in a family with nonsyndromic short stature. The results of this study, in conjunction with those of previous studies, indicate that the genomic region at 16q24.2–q24.3 is prone to submicroscopic deletions and possibly contains a gene(s) or regulatory elements involved in skeletal growth. Our findings need to be validated in future studies.

HGV Database

The relevant data from this Data Report are hosted at the Human Genome Variation Database at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.hgv.3595.

References

Zhao, Q. et al. Clinical and genetic evaluation of children with short stature of unknown origin. BMC Med. Genomics 16, 194 (2023).

Mastromauro, C. & Chiarelli, F. Novel insights into the genetic causes of short stature in children. touchREVIEWS Endocrinol. 18, 49–57 (2022).

Vasques, G. A., Andrade, N. L. M. & Jorge, A. A. L. Genetic causes of isolated short stature. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 63, 70–78 (2019).

Hauer, N. N. et al. Clinical relevance of systematic phenotyping and exome sequencing in patients with short stature. Genet. Med. 20, 630–638 (2018).

Andrade, N. L. M. et al. Diagnostic yield of a multigene sequencing approach in children classified as idiopathic short stature. Endocr. Connect 11, e220214 (2022).

Ockeloen, C. W. et al. Further delineation of the KBG syndrome phenotype caused by ANKRD11 aberrations. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 23, 1176–1185 (2015).

Miyatake, S. et al. A de novo deletion at 16q24.3 involving ANKRD11 in a Japanese patient with KBG syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 161A, 1073–1077 (2013).

Willemsen, M. H. et al. Identification of ANKRD11 and ZNF778 as candidate genes for autism and variable cognitive impairment in the novel 16q24.3 microdeletion syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 18, 429–435 (2010).

Novara, F. et al. Haploinsufficiency for ANKRD11-flanking genes makes the difference between KBG and 16q24.3 microdeletion syndromes: 12 new cases. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 25, 694–701 (2017).

Muranishi, Y. et al. Systematic molecular analyses for 115 karyotypically normal men with isolated non-obstructive azoospermia. Hum. Reprod 39, 1131–1140 (2024).

Loberti, L. et al. Natural history of KBG syndrome in a large European cohort. Hum. Mol. Genet. 31, 4131–4142 (2022).

He, D. et al. Insights into the ANKRD11 variants and short-stature phenotype through literature review and ClinVar database search. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 19, 292 (2024).

Burssed, B., Zamariolli, M., Bellucco, F. T. & Melaragno, M. I. Mechanisms of structural chromosomal rearrangement formation. Mol. Cytogenet. 15, 23 (2022).

Hastings, P. J., Lupski, J. R., Rosenberg, S. M. & Ira, G. Mechanisms of change in gene copy number. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 551–564 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Center for Child Health and Development and Takeda Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the National Center for Child Health and Development and was performed after obtaining written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Narita, C., Utsunomiya, H., Hamada, J. et al. Submicroscopic 16q24.2–q24.3 deletion in a family with nonsyndromic short stature. Hum Genome Var 13, 2 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41439-026-00336-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41439-026-00336-4