Abstract

This study aimed to assess the association of cigarette smoking with radial augmentation index among the Asian general population. We conducted a cross-sectional population-based study including 1593 men and 2671 women aged 40–79 years. Smoking status was ascertained through interviews, and the number of pack-years was calculated. The radial augmentation index was defined as the ratio of central pulse pressure to brachial pulse pressure, as measured using an automated tonometer: the HEM-9000AI (Omron Healthcare co., Kyoto, Japan). There was a higher prevalence of an increased radial augmentation index among current male smokers who smoked ≥ 30 cigarettes/day and all female smokers than among never smokers. After adjusting for known risk factors of atherosclerosis, the multivariable odds ratio (OR) [95% confidence interval (CI)] for a high radial augmentation index for current male smokers who smoked ≥30 cigarettes/day compared with never smokers was 1.9 (1.1–3.4). The multivariable OR (95% CI) for a high radial augmentation index for former female smokers and current female smokers compared with never smokers was 1.8 (1.2–2.7) and 2.5 (1.6–3.9), respectively. Moreover, smoking pack-years was positively associated with a high radial augmentation index in both sexes. There were no relationship between smoking status and high central or brachial pulse pressures among subjects of either sex. In conclusion, cigarette smoking and cumulative smoking exposure were positively associated with an increased radial augmentation index in men who smoked heavily and in women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite the great improvement in controlling the tobacco use epidemic, tobacco smoking continues to be one of the biggest public health problems, especially in low-income and middle-income countries [1]. Cigarette smoking is a major cause of atherosclerosis [2, 3] and cardiovascular diseases [4], and passive smoking has been associated with development of hypertension [5]. Mounting evidence indicates that atherosclerosis plays an important role in the pathophysiology of smoking-induced cardiovascular risk [6,7,8].

The radial augmentation index, a ratio of central pulse pressure to brachial pulse pressure [9], has been widely used as a surrogate measurement of wave reflection. A high augmentation index has been reported to be a marker of increased arterial stiffness [10,11,12] and a predictive factor for cardiovascular events [13]. Several population-based studies reported that cigarette smoking is positively associated with radial augmentation index [14,15,16,17]. In addition, smoking pack-years, a unit for measuring lifetime smoking exposure, is positively associated with aortic augmentation index in young men [18]. However, one previous study failed to show a dose–response relationship in women, probably due to the small number of female smokers [15].

A meta-analysis of 23 population-based studies showed that cigarette smoking was not associated with increased blood pressure [19]. A Japanese population-based study reported no association of smoking status with increased brachial pulse pressure [20]. Another European epidemiological study reported that current smokers had higher central pulse pressure than nonsmokers, despite having similar brachial pulse pressures [21]. The impact of smoking pack-years on central or brachial pulse pressures has not yet been explored.

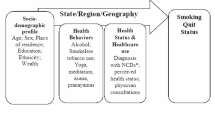

In light of the abovementioned limited evidence, we conducted a study using data from a large community-based cohort study: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS) and aimed (1) to investigate the associations of cigarette smoking with high values of radial augmentation index, central and brachial pulse pressures in both men and women and (2) to determine whether there is a cumulative impact of cigarette smoking on radial augmentation index, central pulse pressure, and brachial pulse pressure.

Methods

Study subjects

We used data from the CIRCS, a prospective community-based study of cardiovascular disease in Japan since 1963 [22]. Arterial stiffness was measured in 1593 men and 2671 women aged 40–79 years who were enrolled in the annual cardiovascular risk surveys in three communities: Kyowa town in Ibaraki Prefecture, Ikawa town in Akita Prefecture, and Yao city in Osaka Prefecture between January 2010 and June 2011. For each subject, physicians, epidemiologists, and trained staff members explained the protocol in detail. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Osaka University.

Measurements

To assess arterial stiffness, trained technicians measured radial augmentation index, central systolic blood pressure, and brachial blood pressure using an automated tonometer (HEM-9000AI, Omron, Healthcare Co., Kyoto, Japan) with all subjects in a seated position after 5 mins of rest [23]. Radial augmentation index was defined as central pulse pressure/brachial pulse pressure × 100 (%). Because radial augmentation index was influenced by heart rate, this index was normalized to 75 beats/min according to the previous guidelines [24]. Central pulse pressure was defined as the central systolic blood pressure minus the brachial diastolic blood pressure, and brachial pulse pressure was defined as the brachial systolic blood pressure minus the diastolic blood pressure.

Trained observers ascertained the subjects’ smoking status, number of cigarettes smoked per day, and duration of smoking. Subjects who had quit smoking for at least the past 3 months were defined as former smokers. Those who currently smoked ≥ 1 cigarette/day were defined as current smokers and stratified into three groups (1–19, 20–29, and ≥ 30 cigarettes/day) in men and two groups (1–19 and ≥ 20 cigarettes/day) in women. Smoking pack-years of current smokers was calculated as the mean number of cigarette packs smoked per day multiplied by the number of years of smoking and stratified into three groups (<30, 30–44, and ≥ 45) in men and three groups (<12, 12–23, and ≥ 24) in women according to the tertiles of pack-years in each sex.

During health checkups, height in stocking feet and weight in light clothing were measured. The usual weekly intake of alcohol was evaluated in units of “go”, a traditional Japanese unit of volume equal to 23 g of ethanol and converted into grams of ethanol per day [25]. Seated right arm systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured in all subjects after 5 mins of rest by trained observers using the HEM-9000AI. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a fasting glucose level of ≥ 7.8 mmol/L, a nonfasting glucose level of ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, or the use of medication for diabetes mellitus. For the measurement of serum lipids and glucose, blood was drawn from seated subjects who had not fasted into a plain, siliconized glass tube, and the serum was separated within 30 mins. Serum glucose was measured using the hexokinase method, and total serum and HDL cholesterol were measured using enzymatic methods and an automatic analyzer (Hitachi 7250, Hitachi Medical Corp., Ibaraki, Japan) at the Osaka Medical Centre for Health Science and Promotion, an international member of the US National Cholesterol Reference Method Laboratory Network (CRMLN) [26].

Statistical analysis

We analyzed the sex-specific prevalence of high radial augmentation indices, central pulse pressures, and brachial pulse pressures according to the smoking status to assess the impact of cigarette smoking on arterial stiffness. In this study, a value higher than the lower limit of the highest quintile of the radial augmentation index (≥ 88% in men and ≥ 94% in women) was defined as a high radial augmentation index. The same concept was applied to define high central and brachial pulse pressures (central pulse pressure: ≥ 55 mmHg in men and ≥ 56 mmHg in women; brachial pulse pressure: ≥ 65 mmHg in men and ≥ 64 mmHg in women). Smoking status was divided into five groups (never, former, and current smokers who smoked 1–19, 20–29, and ≥ 30 cigarettes/day) in men and four groups (never, former, and current smokers who smoked 1–19 and ≥ 20 cigarettes/day) in women. Dunnett's test was used to compare the differences in each variable of interest between never smokers and subjects with other smoking statuses. We calculated the age- and multivariable odds ratios (ORs) [95% confidence intervals (CIs)] of a high radial augmentation index, central pulse pressure, and brachial pulse pressure according to smoking status using logistic regression analysis. Tests for trend across different groups of smoking pack-years were conducted by assigning median values for smoking pack-years: 0 in never smokers, 21 in the < 30 pack-years group, 38 in the 30–44 pack-years group, and 54 in the ≥ 45 pack-years group in men and 0 in never smokers, 7.75 in the < 12 pack-years group, 16.875 in the 12–23 pack-years group, and 31.75 in the ≥ 24 pack-years group in women. The potential confounding factors included age (years), height (cm), weight (kg), serum non-HDL cholesterol and HDL cholesterol (mmol/L), heart rate (beats/min), alcohol intake (g/day), diabetes mellitus, and the use of antihypertensive medication (yes or no). Because the radial augmentation index was calculated using pulse pressures, we did not adjust for blood pressure in the multivariable models. All analyses were conducted using the SAS statistical package version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, CA). All P-values for statistical tests were two-tailed, and P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Among the 1593 male and 2671 female subjects, 436 (27.4%) men and 122 (4.6%) women were current smokers. Table 1 shows the sex-specific, age-adjusted mean values ± SEs and proportions of selected atherosclerosis risk factors according to smoking status. Current smokers were younger and had higher alcohol intake in both sexes than never smokers. Current female smokers had lower serum HDL cholesterol levels than never smokers. Additionally, current smokers had higher radial augmentation indices than never smokers, while their central and brachial pulse pressures were similar to those of never smokers. There were no significant differences in the mean values of systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, height, weight, serum non-HDL cholesterol, the proportion of diabetes mellitus, and the use of antihypertension medication according to smoking status among subjects of either sex.

Sex-specific, and age-specific and multivariable ORs (95% CIs) of high radial augmentation index, central pulse pressure, and brachial pulse pressure according to the smoking status are shown in Table 2. Current male smokers who smoked ≥ 30 cigarettes/day had a higher age-adjusted prevalence of a high radial augmentation index than never smokers. Former and current female smokers had a similarly high prevalence. These associations did not change substantially after further adjustment for known atherosclerosis risk factors: the multivariable OR (95% CI) of a high radial augmentation index for current male smokers who smoked ≥ 30 cigarettes/day compared with never smokers was 1.9 (1.1–3.4). The multivariable ORs (95% CIs) of a high radial augmentation index in former and current female smokers compared with never smokers were 1.8 (1.2–2.7) and 2.5 (1.6–3.9), respectively. Moreover, current female smokers who smoked ≥ 20 cigarettes/day had a relatively higher prevalence of a high radial augmentation index and the multivariable OR (95% CI) was 3.6 (1.7–7.6). There was no material difference in the prevalence of high central or brachial pulse pressures according to smoking status among subjects of either sex.

We also analyzed the impact of smoking pack-years on radial augmentation index, central pulse pressure, and brachial pulse pressure. The age-specific and multivariable ORs (95% CIs) of high values of these variables are shown in Table 3. Smoking pack-years was positively associated with the prevalence of a high radial augmentation index among subjects of both sexes, and this positive association was more evident in women than in men. Further adjustment for known atherosclerotic risk factors did not significantly alter these associations: in men, the multivariable ORs (95% CIs) of a high radial augmentation index in current smokers with <30, 30–44, and ≥ 45 smoking pack-years compared with never smokers were 0.9 (0.5–1.4), 1.8 (1.2–2.8), and 1.6 (1.1–2.4), respectively; in women, the multivariable ORs (95% CIs) of a high radial augmentation index in current smokers with <12, 12–23, and ≥ 24 smoking pack-years compared with never smokers were 1.4 (0.6–3.2), 3.3 (1.7–6.5), and 2.3 (1.2–4.5), respectively. There were no significant differences in the prevalence of high central or brachial pulse pressures according to smoking pack-years among subjects of either sex.

Discussion

In this population-based study of 4264 subjects aged 40–79 years, current male smokers who smoked ≥ 30 cigarettes/day were twice as likely to have a high radial augmentation index than the never smokers, and current female smokers were two to four times as likely to have a high radial augmentation index than the never smokers. Furthermore, smoking pack-years was positively associated with a high radial augmentation index among subjects of both sexes. There was no association between cigarette smoking and high central or brachial pulse pressure among subjects of either sex.

Several previous studies have reported that cigarette smoking was positively associated with radial augmentation index. An epidemiological study of 143 Czech men and 148 women aged 25–65 years reported that current smokers had a higher age-adjusted mean radial augmentation index than the never smokers of both sexes (71.1% vs. 62.9%; P-value < 0.01 in men; 84.0% vs. 74.4%; P-value < 0.01 in women) [14]. The Tanushimaru study of 769 Japanese men and 1157 women aged 40–95 years reported a dose–response relationship between smoking status and age-adjusted mean radial augmentation index in men (80.9% in never smokers, 81.5% in former smokers, 83.9% in current smokers who smoked 1–19 cigarettes/day, and 84.6% in current smokers who smoked ≥ 20 cigarettes/day, P-value for trend=0.01). A similar trend was not observed in women (P-value for trend=0.127) [15]. The Nagahama study of 8557 Japanese men and women aged 30–75 years reported that cigarette smoking was positively associated with radial augmentation index in all subjects, using multiple linear regression analysis, but that study did not provide sex-specific results [16]. Another population-based study of 909 Japanese men whose mean age was 58 years reported that current smokers had a higher prevalence of a high radial augmentation index, and the multivariable OR (95% CI) of a high radial augmentation index (mean > 79.4%) in current smokers compared with never smokers was 1.74 (1.27–2.43) (P-value < 0.001) [17].

In our study, we found that cigarette smoking was strongly associated with a high radial augmentation index in women more commonly than in men. Women have generally shorter stature and arterial tree length than men. These anatomical characteristics result in earlier return of the reflected wave to the central aorta in systole rather than in diastole [27], leading to increased pulse pressure and a higher radial augmentation index. Due to this sex difference in the vascular tree, a certain threshold of tobacco exposure is needed to affect the radial augmentation index in men, but any tobacco exposure in women seems to have a greater impact on radial augmentation index.

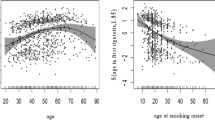

Smoking pack-years is a measurement of lifetime smoking exposure. Our findings indicated that smoking pack-years was positively associated with the prevalence of a high radial augmentation index among subjects of both sexes. The atherosclerotic risk in young adults (ARYA) study of 330 men aged 27–30 years in the Netherlands reported that smoking pack-years was positively associated with a high aortic augmentation index, which is a ratio of the augmentation of central systolic pressure above the first systolic pressure to the central pulse pressure, using the SphygmoCor system; the aortic augmentation index showed a 0.31% increase for each additional smoking pack-year (P-value < 0.05) [18]. Regardless of how the augmentation index is measured, the radial augmentation index is well-correlated with the aortic augmentation index (r=0.91, P-value < 0.001) [28]. We conducted a similar linear regression analysis and found that the radial augmentation index increased by 0.04% in men (P-value = 0.03) and 0.12% in women (P-value < 0.001) for each additional smoking pack-year.

Some epidemiological studies have reported that the central and brachial pulse pressures were associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events [29, 30]. Cigarette smoking can increase blood pressure acutely, but limited evidence was shown about a chronic effect of cigarette smoking on blood pressure [31]. A Mendelian randomization meta-analysis of 23 population-based studies reported no association between smoking and increased blood pressure [19]. In a Japanese population-based study of 2634 men and women ≥ 68 years, cigarette smoking was not associated with changes in brachial pulse pressure [20]. Additionally, a European epidemiological study of 299 men and women aged 25–84 years reported that current smokers had higher central pulse pressures than nonsmokers (29.4 mmHg vs. 30.8 mmHg, P = 0.043), but no difference in brachial pulse pressure was reported [21]. In our study, we analyzed the association between cigarette smoking with higher values of central and brachial pulse pressures among subjects of both sexes and found no statistical differences in pulse pressures according to smoking status.

Our study has several strengths. First, we had a large sample size, detailed smoking histories and internal quality control for data collection [22] when assessing the association of cigarette smoking with a high radial augmentation index. Second, we used data from a large community-based study, which is likely to make our findings generalizable to a larger population. Third, we used not only the radial augmentation index but also central and brachial pulse pressures to examine the impact of cigarette smoking on arterial stiffness. In terms of the limitations of our study, arterial stiffness was determined only by the radial augmentation index. Unfortunately, we did not measure other parameters of arterial stiffness such as pulse wave velocity (PWV) and ankle-brachial pressure index (ABI) when assessing the impact of cigarette smoking on changes in arterial stiffness. These parameters have been shown to change with cigarette smoking [32, 33]. Last, we could not draw a causal association because of the cross-sectional design of our study.

In conclusion, cigarette smoking and cumulative smoking exposure were positively associated with increased arterial stiffness evaluated by the radial augmentation index in men who smoked heavily and in women.

References

Carroll AJ, Labarthe DR, Huffman MD, Hitsman B. Global tobacco prevention and control in relation to a cardiovascular health promotion and disease prevention framework: a narrative review. Prev Med. 2016;93:189–97.

Howard G, Wagenknecht LE, Burke GL, Diez-Roux A, Evans GW, McGovern P, et al. Cigarette smoking and progression of atherosclerosis: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. JAMA. 1998;279:119–24.

Baldassarre D, Castelnuovo S, Frigerio B, Amato M, Werba JP, De Jong A, et al. Effects of timing and extent of smoking, type of cigarettes, and concomitant risk factors on the association between smoking and subclinical atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2009;40:1991–8.

Mons U, Müezzinler A, Gellert C, Schöttker B, Abnet CC, Bobak M, et al. Impact of smoking and smoking cessation on cardiovascular events and mortality among older adults: meta-analysis of individual participant data from prospective cohort studies of the CHANCES consortium. BMJ. 2015;350:h1551.

Wu L, Yang S, He Y, Liu M, Wang Y, Wang J, et al. Association between passive smoking and hypertension in Chinese non-smoking elderly women. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:399–404.

Messner B, Bernhard D. Smoking and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction and early atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:509–15.

McEvoy JW, Blaha MJ, DeFilippis AP, Lima JA, Bluemke DA, Hundley WG, et al. Cigarette smoking and cardiovascular events: role of inflammation and subclinical atherosclerosis from the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:700–9.

Ambrose JA, Barua RS. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1731–7.

Munir S, Guilcher A, Kamalesh T, Clapp B, Redwood S, Marber M, et al. Peripheral augmentation index defines the relationship between central and peripheral pulse pressure. Hypertension. 2008;51:112–8.

Sako H, Miura S, Kumagai K, Saku K. Associations between augmentation index and severity of atheroma or aortic stiffness of the descending thoracic aorta by transesophageal echocardiography. Circ J. 2009;73:1151–6.

McEniery CM, Yasmin, Hall IR, Qasem A, Wilkinson IB, Cockcroft JR. Normal vascular aging: differential effects on wave reflection and aortic pulse wave velocity: the Anglo-Cardiff Collaborative Trial (ACCT). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1753–60.

Rosenbaum D, Giral P, Chapman J, Rached FH, Kahn JF, Bruckert E, et al. Radial augmentation index is a surrogate marker of atherosclerotic burden in a primary prevention cohort. Atherosclerosis. 2013;231:436–41.

Chirinos JA, Kips JG, Jacobs DR Jr, Brumback L, Duprez DA, Kronmal R, et al. Arterial wave reflections and incident cardiovascular events and heart failure: MESA (multiethnic study of atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2170–7.

Filipovský J, Tichá M, Cífková R, Lánská V, Stastná V, Roucka P. Large artery stiffness and pulse wave reflection: results of a population-based study. Blood Press. 2005;14:45–52.

Tsuru T, Adachi H, Enomoto M, Fukami A, Kumagai E, Nakamura S, et al. Augmentation index (AI) in a dose-response relationship with smoking habits in males: The Tanushimaru study. Med (Baltim). 2016;95:e5368.

Tabara Y, Takahashi Y, Setoh K, Muro S, Kawaguchi T, Terao C, et al. Increased aortic wave reflection and smaller pulse pressure amplification in smokers and passive smokers confirmed by urinary cotinine levels: the Nagahama Study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2673–7. Nagahama Study Group.

Sugiura T, Dohi Y, Takase H, Yamashita S, Fujii S, Ohte N. Oxidative stress is closely associated with increased arterial stiffness, especially in aged male smokers without previous cardiovascular events: a cross-sectional study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24:1186–98.

Van Trijp MJ, Bos WJ, Uiterwaal CS, Oren A, Vos LE, Grobbee DE, et al. Determinants of augmentation index in young men: the ARYA study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:825–30.

Linneberg A, Jacobsen RK, Skaaby T, Taylor AE, Fluharty ME, Jeppesen JL, et al. Effect of smoking on blood pressure and resting heart rate: a mendelian randomization meta-analysis in the CARTA Consortium. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2015;8:832–41.

Davarian S, Crimmins E, Takahashi A, Saito Y. Sociodemographic correlates of four indices of blood pressure and hypertension among older persons in Japan. Gerontology. 2013;59:392–400.

Markus MR, Stritzke J, Baumeister SE, Siewert U, Baulmann J, Hannemann A, et al. Effects of smoking on arterial distensibility, central aortic pressures and left ventricular mass. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2593–601.

Imano H, Kitamura A, Sato S, Kiyama M, Ohira T, Yamagishi K, et al. Trends for blood pressure and its contribution to stroke incidence in the middle-aged Japanese population: the circulatory risk in communities study (CIRCS). Stroke. 2009;40:1571–7.

Kohara K, Tabara Y, Oshiumi A, Miyawaki Y, Kobayashi T, Miki T. Radial augmentation index: a useful and easily obtainable parameter for vascular aging. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:11S–14S.

Wilkinson IB, MacCallum H, Flint L, Cockcroft JR, Newby DE, Webb DJ. The influence of heart rate on augmentation index and central arterial pressure in humans. J Physiol. 2000;525:263–70.

Kirkendall WM, Feinleib M, Freis ED, Mark AL. Recommendations for human blood pressure determination by sphygmomanometers. Subcommittee of the AHA Postgraduate Education Committee. Circulation. 1980;62:1146A–1155A.

Nakamura M, Sato S, Shimamoto T. Improvement in Japanese clinical laboratory measurements of total cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol by the US cholesterol reference method laborator network. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2003;10:145–53.

Smulyan H, Asmar RG, Rudnicki A, London GM, Safar ME. Comparative effects of aging in men and women on the properties of the arterial tree. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1374–80.

Takazawa K, Kobayashi H, Shindo N, Tanaka N, Yamashina A. Relationship between radial and central arterial pulse wave and evaluation of central aortic pressure using the radial arterial pulse wave. Hypertens Res. 2007;30:219–28.

Winston GJ, Palmas W, Lima J, Polak JF, Bertoni AG, Burke G, et al. Pulse pressure and subclinical cardiovascular disease in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26:636–42.

Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kizer JR, Okin PM, Lee ET, Wang W, et al. High central pulse pressure is independently associated with adverse cardiovascular outcome the strong heart study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1730–44.

Virdis A, Giannarelli C, Neves MF, Taddei S, Ghiadoni L. Cigarette smoking and hypertension. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:2518–25.

Cui R, Iso H, Yamagishi K, Tanigawa T, Imano H, Ohira T, et al. Relationship of smoking and smoking cessation with ankle-to-arm blood pressure index in elderly Japanese men. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:243–8.

Camplain R, Meyer ML, Tanaka H, Palta P, Agarwal SK, Aguilar D, et al. Smoking behaviors and arterial stiffness measured by pulse wave velocity in older adults: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29:1268–75.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Emeritus Yoshio Komachi (University of Tsukuba), Professor Emeritus Hideki Ozawa (Oita Medical University), Former professor Minoru Iida (Kansai University of Welfare Sciences), Dr. Yoshinori Ishikawa (Consultant of Osaka Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention), Professor Yoshihiko Naito (Mukogawa Women’s University), Dr. Shinichi Sato (Chiba Prefectural Institute of Public Health), Professor Tomonori Okamura (Keio University) for their support in conducting long-term cohort studies, and Wen Zhang, Ph.D., Yuanying Li, Ph.D., Keyang Liu, Ph.D., and Dr. Krisztina Gero, Osaka University, for their excellent technical assistance and help with data collection. This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid Research C (No. 21590691 in 2009–2011) from the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Labour, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CIRCS collaborators

CIRCS collaborators

The CIRCS investigators are: Takeo Okada, Mina Hayama-Terada, Shinichi Sato, Yuji Shimizu and Masahiko Kiyama, Osaka Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention; Akihiko Kitamura, Hironori Imano, Renzhe Cui, Isao Muraki and Hiroyasu Iso, Osaka University; Kazumasa Yamagishi and Tomoko Sankai, University of Tsukuba; Isao Koyama and Masakazu Nakamura, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center; Masanori Nagao and Mitsumasa Umesawa, Dokkyo Medical University School of Medicine; Tetsuya Ohira, Fukushima Medical University; Koutatsu Maruyama and Isao Saito, Ehime University; Ai Ikeda and Takeshi Tanigawa, Juntendo University.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Cui, R., Eshak, E.S. et al. Association of cigarette smoking with radial augmentation index: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Hypertens Res 41, 1054–1062 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-018-0106-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-018-0106-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The effect of leptin on blood pressure considering smoking status: a Mendelian randomization study

Hypertension Research (2020)

-

Impact of cigarette smoking on nitric oxide-sensitive and nitric oxide-insensitive soluble guanylate cyclase-mediated vascular tone regulation

Hypertension Research (2020)

-

Health advocacy for reducing smoking rates in Hamamatsu, Japan

Hypertension Research (2020)

-

Acute myocardial infarction and stoke after the enactment of smoke-free legislation in public places in Bibai city: data analysis of hospital admissions and ambulance transports

Hypertension Research (2019)