Abstract

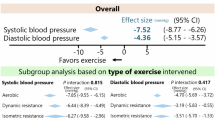

Exercise guidelines for managing hypertension maintain aerobic exercise as the cornerstone prescription, but emerging evidence of the antihypertensive effects of isometric resistance training (IRT) may necessitate a policy update. We conducted individual patient data (IPD) meta-analyses of the antihypertensive effects of IRT. We utilized a one-step fitted mixed effects model and a two-step model with each analyzed trial using a random effects analysis. We classified participants as responders if they lowered their systolic blood pressure (SBP) by ≥5 mmHg, diastolic (DBP) or mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) by ≥3 mmHg. Twelve studies provided data on 326 participants. IRT produced significant reductions in SBP, DBP, and MAP. The SBP responder rates for both groups, or the absolute risk reduction (ARR) between groups, was 28.1% in favor of the IRT group. The number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve one 5 mmHg reduction in SBP was 3.56, 95% CI [2.56, 5.83], or four people. The ARR for DBP was 20.0% in favor of IRT. Therefore, the NNT to achieve one 3 mmHg decrease in DBP was five people, 95% CI [3.22, 11.10]. The ARR for MAP was 28.2% in favor of IRT. Therefore, the NNT to achieve one 3 mmHg reduction in MAP was four people, 95% CI [2.80, 7.42]. Our analyses demonstrated that IRT (three times per week for a total of 8 min of squeezing activity) is able to reduce the participants’ SBP by 6–7 mmHg, equating to a 13% reduction in the risk for myocardial infarction and 22% for stroke.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is the most common circulatory condition, accounting for more than 40% of the cardiovascular disease burden in developed countries [1]. Approximately one-third of adults aged >18 years have hypertension, and in two-thirds of the affected people, it is uncontrolled. Primary healthcare data show that hypertension accounts for ~6% of general practitioner consultations [2]. The resulting financial burden in treating preclinical hypertension is greater than that for any other medical condition, causing sequelae for many chronic illnesses. Prescribed medications may only be effective in 50% of those treated [3], so alternative antihypertensive therapies are required. A recent meta-analysis suggested that most people with hypertension require two or more antihypertensive medications to achieve blood pressure control below 140 mmHg systolic blood pressure (SBP) [4]. Furthermore, Salam and colleagues found in their pooled analysis that triple-therapy, compared to dual-therapy, produced an additional 5.4/3.2 mmHg reduction in SBP/DBP, leading to an additional 13% (58 versus 45%) of people achieving BP control [4]. Another landmark meta-analysis by Xie et al. [5] suggested that an SBP reduction of 7 mmHg was associated with a 13% reduction in myocardial infarctions and 22% fewer strokes [5].

Exercise therapy for hypertension

There is class I, level B evidence that 150 min of weekly aerobic activity (walking, cycling etc.) may limit the dependence on antihypertensive medication in people with hypertension [6], although the optimal exercise training prescription remains unclear. Dynamic resistance training (DRT) may also have an antihypertensive effect [7]. Exercise is medicine and is associated with significant health benefits across virtually all diagnoses, but recent work suggests that the adherence to moderate/vigorous physical activity guidelines [8] may be as low as 14% [9]. While aerobic exercise training (AET) can be as simple as walking in one’s neighborhood, a proportion of people do not exercise because they require access to a gymnasium or equipment to accommodate orthopedic limitations, and some high-risk populations may require professional supervision. Moreover, AET and DRT require significant time commitments to elicit BP reductions. A significant proportion of the population is unwilling or unable to undertake AET or DRT due to time commitments or insufficient motivation, so the adherence rate is often suboptimal [10].

Recent analyses [7, 11, 12] consistently suggest that isometric resistance training (IRT) may be superior to AET and DRT for reducing blood pressure (BP); therefore, IRT is an emerging alternative to AET and DRT (see Table 1). IRT involves a sustained muscular contraction against an immovable load or resistance with no or minimal change in length of the involved muscle group. IRT is therefore a static muscular contraction, such as squeezing a tennis ball in one’s hand, as opposed to an isotonic (concentric and/or eccentric) contraction where the muscle changes in length (shortens and/or lengthens) (e.g., a biceps curl with a dumbbell moving from the hips to shoulder).

As of mid-2019, there are 19 published randomized controlled trials of isometric resistance training, and all but two of these reported significant and unequivocal antihypertensive benefits. The two negative studies both suffered from obvious suboptimal study designs and flaws [13, 14]. The work of Ash in 2017 [13] made the following fairly rudimentary errors: (i) conditioning some of their cohort with aerobic exercise for several weeks and, following only a short wash-out period, implementing isometric training, and then (ii) expecting to detect further BP changes in a subset of only 5 isometric participants. The work of Pagonas in 2017 [14], which utilized aerobic and isometric cohorts that were significantly unmatched in baseline BP, failed to appropriately acknowledge that the 25% withdrawal rate in the aerobic group was statistically significant and then did not subsequently perform intention-to-treat analyses. Moreover, the work was clearly underpowered to detect an unrealistic outcome target of a 7 mmHg or more drop in SBP. Despite the shortcomings of these two works, 90% of the isometric resistance training trials published to date have shown an antihypertensive benefit.

Commonly, IRT protocols utilize a hand-held dynamometer for 4 × 2 min IRT movements at a low intensity of 30% maximal voluntary contraction (MVC), interspersed with 1–3 min rest/session for three sessions/week. IRT can therefore be performed while seated, without a change of clothes and at any time. IRT is a recommended antihypertensive therapy with low cost and time demands [15]. IRT requires little space, uses inexpensive equipment and elicits less physical stress than AET [16]. People unable to perform AET may undertake IRT as IRT has several benefits that may improve adherence: (i) simplicity; (ii) ease of access; (iii) low cost; (iv) no required professional supervision; and (v) shorter total exercise time than AET.

Recent analyses suggest that IRT may elicit BP reductions greater than those observed with dynamic aerobic and resistance exercise [7, 12, 17], but this remains uncertain. Guidelines from 2004 suggest that AET is the preferred exercise modality for BP management, with dynamic resistance training recommended as a supplement [18]. Most IRT studies to date have used clinical measurements, not ambulatory BP measures (ABPM), so white coat hypertension may exist. In 2017, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommended IRT as adjunct antihypertensive therapy [15]. Similarly, in late 2019, a published update to the Exercise & Sport Science Australia (ESSA) position statement on hypertension included a similar recommendation for IRT [19]. These recent translational research initiatives were informed by our pooled analyses [7, 11, 12, 16, 17] and trial work [20,21,22]. Nevertheless, the adherence to, economic benefits of and mechanisms of IRT remain unclear.

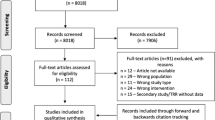

In 2019, we conducted a systematic review and individual patient data (IPD) analysis of the antihypertensive effects of IRT, and some of these results have been published previously [12]. The primary aim of this present work is to describe additional, unreported findings from our IPD meta-analysis on the antihypertensive effects of IRT, in terms of evidence-based practice [12]. Finally, we aim to evaluate the cost of exercise-based guidelines in the management of hypertension.

Methods

Our IPD methods have been described previously [12], but in summary, we conducted an IPD meta-analysis of all available primary datasets from randomized, controlled trials of IRT lasting >3 weeks. We collected the pre- and post-IRT BP values and patient demographic data. Medication data were not available.

For the one-step IPD analysis, we fitted mixed effects models to the change in BP (systolic, diastolic and mean arterial) with treatment as a fixed effect, treating each study as a random effect.

The two-step analyses were conducted with each analyzed trial using a random effects model for each outcome. A random effects model was preferred due to the high degree of clinical heterogeneity across the individual trials, which included different patient populations and comparators.

Evidence-based medicine analysis

For the sole purposes of this manuscript, we wish to define our IPD participants in terms of ‘responders’ and ‘nonresponders’. We therefore defined ‘responders’ as any participant who showed:

-

(i)

Systolic blood pressure (SBP)—a 5 mmHg or greater reduction in SBP.

-

(ii)

Diastolic blood pressure (DBP)—a 3 mmHg or greater reduction in DBP.

-

(iii)

Mean arterial pressure (MAP)—a 3 mmHg or greater reduction in MAP.

We chose these values as they were similar to the effect size of adding a third BP agent to the established dual therapy, as reported by Salam et al. in their 2019 meta-analysis [4]. We subsequently calculated the relative risk (RR) for the difference in the number of responders in the IRT and control groups in terms of SBP, DBP, and MAP. The proportion of responders could then be used to calculate the number needed to treat (NNT) and estimate the reduction in risk for MI and stroke using the analyses of Xie et al. [5]. In addition, based upon the findings presented here, we made some recommendations for the addition of IRT to the existing exercise-based guidelines to manage hypertension.

Results

Evidence-based analysis of the antihypertensive effects of IRT

Our IPD analysis included data from 326 participants, of whom 191 completed IRT and 135 were controls.

As previously reported, our IPD meta-analysis (one-step ANOVA) showed that IRT elicited a more than 6 mmHg (p < 0.00001) improvement in SBP compared to the control method [12], while our two-step meta-analysis showed the reduction in SBP was > 7.3 mmHg (p < 0.00001).

The one-step analysis of variance showed that IRT reduced the mean DBP by >2.7 mmHg (p = 0.002), while the two-step approach yielded a similar reduction in DBP of >3.2 mmHg (p = 0.0005) [12].

The one-step analysis of variance showed that IRT reduced the mean MAP by >4.1 mmHg (p < 0.0001), while the two-step approach showed that MAP was lowered by >4.6 mmHg (p < 0.00001) [12].

We present for the first time the between-group differences in post-IRT SBP, DBP and MAP for responders and nonresponders.

SBP

Responder rates

At IRT completion, the number of participants exhibiting at least a 5 mmHg reduction in SBP was 106/191 (55.5%) in the IRT group versus 37/135 (27.4%) of the control participants.

This equates to a 28.1% difference in risk reduction in achieving responder status (≥5 mmHg SBP decrease) between the IRT group and controls. The RR of a favorable SBP outcome in the IRT group versus control group was 0.61 (95% CI 0.51–0.74, p < 0.0001).

Absolute risk reduction and NNT

The responder rates for both groups, or the absolute risk reduction (ARR) between groups, was 28.1% in favor of the IRT group. Therefore, the NNT to achieve one 5 mmHg reduction in SBP is 1/ARR = NNT, which equals 1/0.281 = 3.56, 95% CI [2.56, 5.83], or 4 people.

DBP

Responder rates

At IRT completion, the number of participants exhibiting at least a 3 mmHg reduction in DBP was 92/191 (48.2%) in the IRT group versus 38/135 (28.1%) of the control participants.

The RR of a favorable DBP outcome in the IRT group versus control group was 0.67 (95% CI 0.56 to 0.80, p < 0.0001). This equates to a 20.1% difference in RR in achieving responder status ( ≥ 3 mmHg DBP decrease) between the IRT group and controls.

ARR and NNT

The responder rates for both groups, or the ARR between groups, was 20.0% in favor of the IRT group. Therefore, the NNT to achieve one 3 mmHg reduction in DBP is 1/ARR = NNT, or 1/0.201 = 5 people, 95% CI [3.22, 11.10].

MAP

Responder rates

At IRT completion, the number of participants exhibiting at least a 3 mmHg reduction in MAP was 105/191 (55.0%) in the IRT group versus 41/135 (30.4%) of the control participants. This equates to a 24.6% difference in RR in achieving responder status (≥3 mmHg MAP decrease) between the IRT group and controls. The RR for a favorable MAP outcome in the IRT group versus control group was 0.65 (95% CI 0.53–0.78, p < 0.0001).

ARR and NNT

The responder rates for both groups, or the ARR between groups, was 28.2% in favor of the IRT group. Therefore, the NNT to achieve one 3 mmHg reduction in MAP is 1/ARR = NNT, which equals 1/0.246 = 4.07, or 4 people, 95% CI [2.80, 7.42].

Prevention of major adverse cardiac events

A recent landmark meta-analysis has demonstrated that a 7 mmHg reduction in the participants’ SBP, which is possible to detect in a sample of >300 participants as demonstrated in our two-step meta-analysis model, would equate to a 13% reduction in the risk of myocardial infarction and a 22% risk reduction for stroke [5].

Discussion

Our most recent analyses [12] are consistent with two prior meta-analyses to report that IRT, compared to no exercise, reduced SBP by an average of −6.8 mmHg (95% CI −7.9, −5.6) in 4–8 weeks [16] and −10.9 mmHg (−14.5, −7.4) [7], respectively. IRT may achieve similar BP reductions with antihypertensive monotherapy [23]. IRT is comparable or superior to dynamic-exercise training (aerobic or resistance) or a combination in reducing BP. Despite this, some researchers remain unconvinced of the efficacy of IRT because few published studies to date have utilized ABPM [24]. Nevertheless, the recent US guidelines recommend IRT as a potential nonpharmacologic therapy to lower BP [15]. The guideline states that IRT has ‘strong supporting evidence’ for antihypertensive effects. In our present work, BP reductions were observed in systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressure and were consistent across the included trials. To date, the impact of IRT in reducing BP has only been examined in small trials with durations of 3–8 weeks [12]. Based upon previous work showing several types of exercise benefits from ABPM [17], we propose that the degree of BP reduction from IRT will translate into important reductions in health-care utilization, including the use of antihypertensive medication, hence reducing healthcare costs. While this existing data is retrospective and is missing key variables, we were unequivocally able to establish almost a 30% difference in response rate (≥5 mmHg SBP decrease) between the IRT group and controls.

Efficacy of IRT

Our analyses have consistently shown that IRT produces antihypertensive effects greater than those previously reported from aerobic exercise training [7, 11, 12]. We therefore suggest that IRT should be recommended by medical and allied health professionals as an antihypertensive therapy: (i) for individuals unwilling, or who have had limited adherence or success with aerobic exercise; (ii) for individuals with resistant or uncontrolled hypertension who are already taking at least two pharmacological antihypertensive agents; (iii) as an adjunct to aerobic exercise and dietary intervention in those who have yet to gain control of their hypertension; and (iv) for individuals with a prehypertension BP > 135/85 mmHg or people who are normotensive at rest but have hypertensive SBP > 200 mmHg or DBP > 100 mmHg upon exertion, such as during stress testing.

Likely mechanism of IRT effect

The mechanism(s) by which IRT reduces BP remains unclear but is most likely mediated through non-neurally mediated reductions in systemic vascular resistance (SVR), as sympathetic nervous activity appears to remain unchanged [25]. Repeated isolated forearm contractions improve flow-mediated endothelial-dependent, nitric oxide (NO)-mediated vasodilation in response to reactive hyperemia [26]. Recently, lower limb IRT has been shown to improve resistance vessel endothelial function [25] and increase active limb artery diameter and blood velocity and flow as well as reduce SVR [27]; however, NO-mediated vasodilation was not measured. This is important as BP is primarily regulated at the resistance vessels, and an increased blood flow/velocity may increase shear stress-mediated basal production of endothelial-dependent vasodilators, e.g., NO derivatives [28].

Feasibility, cost, and benefits

The simplicity and low cost of IRT provides a potentially accessible adjunct BP treatment option. The relatively short training duration and venue flexibility are obvious advantages of IRT and may lead to superior benefits compared to aerobic or dynamic resistance training [7]. Our trial work exhibits 5% nonadherence to IRT with an 8-week follow up [22]. Often, health professionals immediately turn to pharmacological treatment for hypertension as adherence to aerobic exercise is poor [9]. In light of the reported BP reductions [12, 16] and the removal of many common exercise barriers that may prevent good adherence, IRT has great potential for people with hypertension. IRT is intuitively more cost-effective than AET or antihypertensive medication, as the only cost is that of a handgrip dynamometer. An AUS$50 version is widely available and suitable for the general public and offers simple load (squeezing intensity) adjustment. Previous work suggests 20% reductions in medication costs that arise from the antihypertensive effects on lifestyle factors [29]. Since IRT yields larger BP reductions than the current exercise guidelines [7], we suggest potential cost savings via reduced medication use that will significantly benefit healthcare costs.

Safety

IRT, as with other exercise modalities, acutely increases BP during training. However, our recent work [12, 21] unequivocally confirms that IRT produces safe and minimal hemodynamic (double product) responses, and we are yet to record a single adverse event after training in more than 320 participants. IRT is associated with a lower myocardial oxygen demand than AET due to an attenuated increase in heart rate (e.g., coronary perfusion) [21, 30]. Our work has reported that AET elicits a higher heart rate, BP, and double product than IRT and that chest pain and significant ventricular arrhythmias occurred infrequently with static effort [21]. The double product recordings during IRT activity established safe responses and a low potential for adverse events in clinical populations [21].

Limitations

While our evidence-based analyses are based upon the highest possible level and class of evidence, an IPD meta-analysis, we have made two major assumptions in the presentation of our results. First, the determination of the effect size of responders, which is a surrogate of clinical significance, was based upon a meta-analysis of antihypertensive effects of polypharmacy; therefore, the datasets were not generated from a common study design or trial population [4]. Second, the determination of the likely reduction in risk for major adverse cardiac events was also based upon a dataset generated from a separate meta-analysis. This alternative analysis had equated SBP reductions, of a similar degree to those seen in our IPD analysis, to adverse event rates, so again the comparisons drawn were not from a common study design or trial populations [5].

Conclusions

Our recent IPD meta-analysis has demonstrated that IRT (three times per week for a total of 8 min of squeezing activity) is able to reduce a participant’s SBP by 6–7 mmHg. A similar degree of BP reduction from taking prescribed medication has been shown to equate to a 13% reduction in the risk for myocardial infarction and a 22% risk reduction for stroke.

Recommendations for those most likely to benefit from IRT

We recommended that IRT be used as an antihypertensive therapy:

-

(i)

for individuals unwilling or unable to complete aerobic exercise or who have had limited adherence or success with it;

-

(ii)

for individuals with resistant or uncontrolled hypertension who are already taking at least two pharmacological antihypertensive agents;

-

(iii)

as an adjunct to aerobic exercise and dietary intervention in those who have yet to gain control of their hypertension;

-

(iv)

in individuals with a prehypertension BP > 135/85 mmHg or people who are normotensive at rest but have a hypertensive SBP > 200 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure > 100 mmHg upon exertion, such as during stress testing.

References

Begg SVT, Barker B, Stevenson C, Stanley L, Lopez AD. The burden of disease and injury in Australia 2003. Canberra: AIHW. PHE82.

AIHW. http://www.aihw.gov.au/high-blood-pressure/ (2010).

Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988-2000. JAMA. 2003;290:199–206.

Salam AAE, Hsuc B, Websterb R, Patelb A, Rodgers A. Efficacy and safety of triple versus dual combination blood pressure-lowering drug therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertension. 2019;37:1567–73.

Xie X, Atkins E, Lv J, Bennett A, Neal B, Ninomiya T, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:435–43.

Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bezanson JL, Dolor RJ, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women–2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1404–23.

Cornelissen VA, Smart NA. Exercise training for blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e004473.

WHO. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: WHO; 2010.

Luzak A, Heier M, Thorand B, Laxy M, Nowak D, Peters A, et al. Physical activity levels, duration pattern and adherence to WHO recommendations in German adults. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0172503.

Jones F, Harris P, Waller H, Coggins A. Adherence to an exercise prescription scheme: the role of expectations, self-efficacy, stage of change and psychological well-being. Br J Health Psychol. 2005;10:359–78.

Inder JD, Carlson DJ, Dieberg G, McFarlane JR, Hess NC, Smart NA. Isometric exercise training for blood pressure management: a systematic review and meta-analysis to optimize benefit. Hypertens Res. 2016;39:88–94.

Smart NA, Way D, Carlson D, Millar P, McGowan C, Swaine I, et al. Effects of isometric resistance training on resting blood pressure: individual participant data meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2019;37:1927–38.

Ash GI, Taylor BA, Thompson PD, MacDonald HV, Lamberti L, Chen MH, et al. The antihypertensive effects of aerobic versus isometric handgrip resistance exercise. J Hypertens. 2017;35:291–9.

Pagonas N, Vlatsas S, Bauer F, Seibert FS, Zidek W, Babel N, et al. Aerobic versus isometric handgrip exercise in hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. J Hypertens. 2017;35:2199–206.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:e127–e248.

Carlson DJ, Dieberg G, Hess NC, Millar PJ, Smart NA. Isometric exercise training for blood pressure management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:327–34.

Cornelissen VA, Buys R, Smart NA. Endurance exercise beneficially affects ambulatory blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2013;31:639–48.

Pescatello LS, Franklin BA, Fagard R, Farquhar WB, Kelley GA, Ray CA. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and hypertension. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:533–53.

Sharman JE, Smart, NA, Coombes, JS, Stowasser M. Exercise and sport science Australia position stand update on exercise and hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2019. In Press.

Hess NC, Carlson DJ, Inder JD, Jesulola E, McFarlane JR, Smart NA. Clinically meaningful blood pressure reductions with low intensity isometric handgrip exercise. A randomized trial. Physiological Res. 2016;65:461–8.

Carlson DDG, McFarlane JR, Smart NA. Rate pressure product responses during an acute session of isometric resistance training. J Hypertension Cardiol 2017;2:1–11.

Carlson DJ, Inder J, Palanisamy SK, McFarlane JR, Dieberg G, Smart NA. The efficacy of isometric resistance training utilizing handgrip exercise for blood pressure management: a randomized trial. Medicine. 2016;95:e5791.

Wong GW, Boyda HN, Wright JM. Blood pressure lowering efficacy of partial agonist beta blocker monotherapy for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:CD007450.

Farah BQ, Rodrigues SLC, Silva GO, Pedrosa RP, Correia MA, Barros MVG, et al. Supervised, but not home-based, isometric training improves brachial and central blood pressure in medicated hypertensive patients: a randomized controlled trial. Front Physiol. 2018;9:961.

Badrov MB, Bartol CL, Dibartolomeo MA, Millar PJ, McNevin NH, McGowan CL. Effects of isometric handgrip training dose on resting blood pressure and resistance vessel endothelial function in normotensive women. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113:2091–2100.

Cook M, Smart NA, Van, der Touw T. Predicting blood flow responses to rhythmic handgrip exercise from one second isometric contractions. Physiological Res. 2016;65:581–9.

Baross AW, Wiles JD, Swaine IL. Effects of the intensity of leg isometric training on the vasculature of trained and untrained limbs and resting blood pressure in middle-aged men. Int J Vasc Med. 2012;2012:964697.

Goto C, Nishioka K, Umemura T, Jitsuiki D, Sakagutchi A, Kawamura M, et al. Acute moderate-intensity exercise induces vasodilation through an increase in nitric oxide bioavailiability in humans. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:825–30.

Kurz RW, Pirker H, Potz H, Dorrscheidt W, Uhlir H. Evaluation of costs and effectiveness of an integrated outpatient training program for hypertensive patients. Wien klinische Wochenschr. 2005;117:526–33.

Peters PG, Alessio HM, Hagerman AE, Ashton T, Nagy S, Wiley RL. Short-term isometric exercise reduces systolic blood pressure in hypertensive adults: possible role of reactive oxygen species. Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:199–205.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smart, N.A., Gow, J., Bleile, B. et al. An evidence-based analysis of managing hypertension with isometric resistance exercise—are the guidelines current?. Hypertens Res 43, 249–254 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0360-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0360-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Safety, efficacy and delivery of isometric resistance training as an adjunct therapy for blood pressure control: a modified Delphi study

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

Postexercise hypotension predicts the chronic effects of resistance training in middle-aged hypertensive individuals: a pilot study

Hypertension Research (2021)