Abstract

The optimal exercise-training characteristics for reducing blood pressure (BP) are unclear. We investigated the effects of 6-weeks of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) or moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) on BP and aortic stiffness in males with overweight or obesity. Twenty-eight participants (18–45 years; BMI: 25–35 kg/m2) performed stationary cycling three times per week for 6 weeks. Participants were randomly allocated (unblinded) to work-matched HIIT (N = 16; 10 × 1-min intervals at 90–100% peak workload) or MICT (N = 12; 30 min at 65–75% peak heart rate). Central (aortic) and peripheral (brachial) BP and aortic stiffness was assessed before and after training. There were no significant group × time interactions for any BP measure (all p > 0.21). HIIT induced moderate reductions in central (systolic/diastolic ∆: −4.6/−3.5 mmHg, effect size d = −0.51/−0.40) and peripheral BP (−5.2/−4 mmHg, d = −0.45/−0.47). MICT induced moderate reductions in diastolic BP only (peripheral: −3.4 mmHg, d = −0.57; central: −3 mmHg, d = −0.50). The magnitude of improvement in BP was strongly negatively correlated with baseline BP (r = −0.66 to −0.78), with stronger correlations observed for HIIT (r = −0.73 to −0.88) compared with MICT (r = −0.43 to −0.61). HIIT was effective for reducing BP (~3–5 mmHg) in the overweight to obese cohort. Exercise training induced positive changes in central (aortic) BP. The BP-lowering effects of exercise training are more prominent in those with higher baseline BP, with stronger correlation in HIIT than MICT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, with high prevalence (~31% of adults world-wide) and significant global economic cost [1,2,3,4]. Exercise training is an effective intervention to improve blood pressure (BP), with typical reductions following aerobic exercise training in the magnitude of 5–8 mmHg in patients with hypertension—slightly lower magnitude to commonly-used antihypertensive medication [5]. However, the optimal exercise characteristics for managing BP in hypertensive and pre-hypertensive populations are still unclear.

High-intensity interval training (HIIT), referring to repeated bursts of vigorous activity interspersed with periods of rest, is becoming a popular alternative to moderate-intensity continuous exercise (MICT). This is due to its relative time-efficiency and the accumulating evidence supporting its efficacy for improving a range of health and fitness measures in both healthy and clinical populations [6,7,8,9]. Recent meta-analyses report HIIT to show greater effectiveness for improving vascular function (specifically brachial artery flow-mediated dilation) compared with MICT [8] and reduce BP to a similar magnitude as MICT in adults with hypertension [10]. However, these findings are based on a low number of published studies and there is still limited comparative evidence of the chronic effects of HIIT and MICT with regards to BP and aortic stiffness.

Emerging data suggests central BP is more strongly predictive of future cardiovascular events than traditional brachial BP [11,12,13,14,15] and that peripheral BP is a relatively poor surrogate for central BP which is invariably lower than corresponding brachial values [11]. Therefore, it is important to explore the comparative effects of HIIT or MICT exercise training formats on measures of central (aortic) BP and aortic stiffness. Antihypertensive medications, especially beta-blockers, can have differential effects on central and peripheral BP [16, 17]; however, whether exercise training induces differential effects is not yet clear. Also unclear is whether exercise-training-induced changes in BP is mediated by changes in aortic stiffness. Therefore, the aim of this study is to compare the effect of 6-weeks of HIIT or MICT on central (aortic) and peripheral (brachial) measures of BP and aortic stiffness in males with overweight or obesity.

Methods

Participants

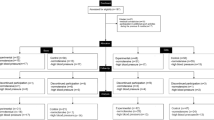

Thirty-seven apparently healthy, sedentary, men with overweight or obesity participated in the study. Nine participants did not complete the training, leaving 28 participants who completed the study (HIIT n = 16; MICT n = 12) (Fig. 1). The primary inclusion criteria were male sex, aged 18–45 years, body mass index (BMI) 25–35 kg/m2, and predominantly sedentary (completing <30 min of structured physical activity per week). Participants were excluded if they had previously been diagnosed with hypertension (using Australian guidelines ≥140/90 mmHg); other cardiovascular-risk factors such as diabetes or hyperlipidemia; a history of cardiac-related diseases; or any uncontrolled medical disorder. Participants were recruited via posters displayed around the University of New South Wales Kensington campus between July 2016 and September 2017. Initial telephone or email contact was used to screen potential recruits for inclusion criteria and contra-indicating medical conditions. If included in the study after this initial screening, participants were re-screened using a formal medical form prior to the initial assessment. This study was approved by the institutional Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC #: HC16432) and registered with the Australia New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12619001409167). All procedures were in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was provided by all participants before participating in the study.

Study design

This report is a component of a larger study investigating the effect of HIIT and MICT on physiology and body composition in males with overweight or obesity. Other results of this trial have already been reported elsewhere [18]. This report focuses solely on BP and aortic stiffness data. The protocol was a randomized trial with MICT acting as the comparator group to HIIT. Exercise training sessions were conducted over 6 weeks and were supervised at a single site where both groups trained in parallel. Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to a HIIT or MICT training group. The random assignment of participants was conducted using a pre-generated list of equally-distributed permuted blocks (http://www.randomization.com). Participants could not be blinded to their training group allocation; however, they were blinded to the primary hypotheses of the study. Researchers performing the BP and aortic stiffness assessments were not blinded to the participant’s training group allocation. The lead investigator (AK) generated the allocation sequence, enroled participants and assigned participants to their groups.

Participant baseline and post-training assessments were conducted in the morning following an overnight fast (for body composition measurement purposes). Participants were also asked to abstain from alcohol and strenuous exercise 24 h prior to each assessment, and to maintain their normal lifestyle and eating habits throughout the study. All post-training assessments were conducted within 2–5 days of the final training session.

Assessments

BP and aortic stiffness

Participants were tested using applanation tonometry (SphygmoCor XCel, AtCor Medical, Sydney, Australia) by trained researchers using protocols as stipulated by expert consensus guidelines [19]. Participants were tested in the supine position after 10 min lying rest. Pulse wave analysis using an upper-arm cuff was applied to assess peripheral (brachial) (primary outcome measure) and central (aortic) (secondary outcome measure) measures of BP. Resting brachial BP was derived from brachial artery waveforms from the right upper arm. From the pulse pressure recorded at the peripheral site, a corresponding aortic pressure waveform was generated via a proprietary digital signal processing and transfer function to then derive indices of central BP (at the aorta). Augmentation index (AIx, secondary outcome measure) was derived from the difference between central systolic BP and the pressure at the inflection point (the merging of forward and reflected waves), expressed as a percentage of pulse pressure. Pulse wave velocity from the carotid artery to the femoral artery (PWVcf), an index of aortic stiffness, was recorded from pulse waveforms recorded simultaneously from the right femoral artery (using a thigh cuff placed at mid-thigh) and the right carotid artery using a hand-held tonometer. The placement of the cuff and tonometer was standardised for each participant across pre- and post-training assessments. PWVcf (secondary outcome measure) was calculated by the ratio of the distance between the carotid and femoral arteries to the transit time (the time delay between the arrival of the pulse wave at the common carotid artery and common femoral artery).

The transient, acute effect of individual exercise sessions on BP was determined as the difference between BP measured immediately before an exercise session compared with BP measured 10 min following the exercise session. BP was assessed at the initial (1st), middle (9th) and final (18th) training sessions. Each measure was taken in the seated position after 10 min of seated rest. Measures were taken using automated, upper-arm cuff-oscillometric sphygmomanometers (Omron HEM-907, Kyoto, Japan).

Training protocols

Participants trained three times per week for 6 weeks. A minimum of 24 h between training sessions was required and no more than two consecutive days of training. All training was conducted on manual-resistance cycle ergometers (Monark 828E Sweden) or electronically-braked cycle ergometers (Monark 928E; for HIIT participants only due to its ability to pre-programme interval training sessions). All sessions were supervised by trained research assistants (undergraduate exercise physiology students). Heart rate (HR) and rating of perceived exertion (RPE) were monitored throughout every training session using a Polar T34 heart rate monitor and unmodified (6–20) Borg scale [20] respectively. For HIIT participants, HR and RPE were recorded at the end of every 2nd interval and recovery period. For MICT participants, HR and RPE were recorded every 5 min.

HIIT sessions consisted of 10 × 1-min intervals at 90–100% Wmax (approximating ~90% HRmax; RPE ~ 15), interspersed with 1 min of active recovery at 15% Wmax. The intensity of training was progressively increased over the 6-week intervention (weeks 1 and 2: 90% Wmax; weeks 3 and 4: 95% Wmax; weeks 5 and 6: 100% Wmax). Each session began with a 3-min warm-up at 35% Wmax (approximating 65% HRmax) and ended with a 2-min cool down at 15% Wmax. MICT sessions consisted of 30 min of continuous exercise at 65–75% HRmax (approximating RPE ~ 11). The intensity of training was progressively increased over the 6-week intervention (weeks 1 and 2: 65% HRmax; weeks 3 and 4: 70% HRmax; weeks 5 and 6: 75% HRmax). Workloads were continually adjusted in each training session to maintain the desired HR (range: 35–50% Wmax). Total exercising time for each session was 24 min for the HIIT group and 30 min for the MICT group.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 24, Chicago, IL, USA). Equality of variance was assessed using Levene’s test and the normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk statistic. Group comparisons [HIIT vs. MICT] were made with independent samples t-tests for baseline characteristics, and within-group changes were analysed using paired t-tests. General linear model repeated measures ANOVA (2 groups × 2 time-points) was applied for all assessment measures. Effect sizes for the pairwise comparisons were calculated using Cohen’s d [21], with the magnitude of effect sizes determined as: small effect = 0.20–0.49, medium effect = 0.50–0.79 and large effect ≥ 0.80. Pearson’s correlation (r) was applied to examine the relationship between baseline BP characteristics and the magnitude of training effect across BP measures. The sample size calculation for the entire study was based on detecting a difference in the change in VO2max (the primary outcome of the overall study, data to be published elsewhere) between the HIIT and MICT groups. Separate sample size calculations were not conducted for each of the overall study’s other health and fitness outcomes including BP and aortic stiffness. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. All data is presented as mean ± SD.

Results

At baseline, there were no significant differences between training groups in general characteristics (age, weight, BMI or VO2max) or in BP and aortic stiffness (all p > 0.11) (Table 1).

Training characteristics

For the participants who completed the study, training attendance was 100% and there was full compliance to training session requirements within each session. There were no serious adverse events during or immediately after any training session. Groups were matched for total training work performed (HIIT: 2806 ± 459 Nm per participant per session; MICT: 2678 ± 546 Nm per participant per session; p = 0.51). HIIT sessions induced higher (p < 0.001) mean HR and RPE (for work intervals) compared with MICT (HIIT: 87 ± 5% HRmax; RPE 14.6 ± 1.7; MICT: 72 ± 3% HRmax; RPE 11.3 ± 0.6).

BP and aortic stiffness

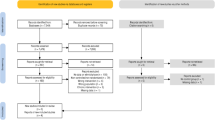

BP and aortic stiffness measures before and after 6 weeks of training are shown in Table 2. BP change scores after 6 weeks of training are shown in Fig. 2. There were no significant group × time interactions for any measure of BP, with the effects ranging from a negligible increase (d = 0.16) to a moderate decrease (d = −0.57). Inter-individual differences in BP responses to exercise training were apparent, with brachial SBP change scores for all participants ranging from −23 mmHg to +16 mmHg (central systolic BP range: −16 to +16 mmHg; brachial diastolic BP range: −15 to +10 mmHg; central diastolic BP range: −16 to +12 mmHg). There were no significant group × time interactions for any measure of aortic stiffness (p > 0.48) and all within-group changes were negligible to small (all d = −0.15 to 0.21, all p > 0.28).

Effect of exercise training on blood pressure. Individual (grey dots) and group data (median and interquartile range) for a central systolic blood pressure (BP), b central diastolic BP, c brachial systolic BP pressure, and d brachial diastolic BP change scores after 6 weeks of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) or moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT)

The magnitude of improvement in BP after training was strongly negatively correlated with baseline BP across measures (r = −0.66 to −0.78), with stronger correlations observed for HIIT (r = −0.73 to −0.88) compared with MICT (r = −0.43 to −0.61).

There was no significant change in BP at 10-min post-training sessions (compared with BP before the session) in either group, along with no significant group difference or group × time interactions for any BP measure across all three exercise sessions combined (all p > 0.12).

Discussion

This study compared the effects of 6-weeks (18 sessions) of HIIT vs. MICT for improving BP and aortic stiffness in previously sedentary, healthy males with overweight or obesity. We found that HIIT decreased BP across a range of indices, including both central aortic and brachial measures, with the magnitude of the reduction in the region of 3–5 mmHg; however, there were no statistical differences in effectiveness between HIIT and MICT on BP outcomes. Secondly, we observed that the magnitude of reduction in BP following exercise training is similar for central (aortic) and peripheral (brachial) measures. Thirdly, the magnitude of BP reduction following exercise training is strongly negatively correlated with baseline BP, and this correlation is stronger in HIIT than for MICT. Finally, the well-documented post-exercise hypotensive response typically observed in the minutes and hours immediately following single sessions of aerobic exercise was not clearly observed in this study for either moderate-intensity or high-intensity cycling exercise sessions.

The observed decreases in BP of ~3–5 mmHg in participants undertaking HIIT is consistent with previously published data from exercise training studies involving normotensive populations [22, 23]. It should be highlighted that while these participants were overweight or obese (mean BMI 28.6) and previously sedentary, this was (at the time) a normotensive population, since an exclusion criterion to study participation was prior-diagnosed hypertension (defined at the time of study design as being >140/90). Mean BP for HIIT participants changed from 133/80 mmHg to 128/76 mmHg following training, which under the new ACC/AHA model published since the study was conducted represents a mean change in categorization from ‘stage 1 hypertension’ (i.e. systolic between 130–139 or diastolic between 80–89) down to ‘elevated’ (i.e. systolic between 120–129 and diastolic less than 80) [24]. Therefore, it could be argued that the HIIT intervention provided meaningful, clinical change in this participant cohort. In contrast, MICT induced small to moderate sized effects in only diastolic BP (~3 mmHg reduction in central and peripheral diastolic pressure), and mean BP for MICT participants was 129/76 mmHg at baseline (categorized under ACC/AHA guidelines as ‘elevated’) and 130/72 mmHg following training (‘stage 1 hypertension’). However, considering no significant group × time interactions were observed, findings regarding the relative efficacy of HIIT and MICT need to be interpreted cautiously, and the findings do diverge from similar recent small-sample randomized trials [25].

Our exercise training study is one of very few to also assess central (aortic) BP and aortic stiffness. Central measures of BP appear to be a more valuable and reliable indicator than peripheral measures for predicting cardiovascular mortality and target-organ damage [11,12,13,14,15]. HIIT participants showed improved central (aortic) BP similar in magnitude of change to the peripheral (brachial) measure (effect size −0.4 and −0.51 for central SBP and DBP changes respectively, compared with effect size −0.45 and −0.47 for the brachial BP measures respectively). This improvement in central BP occurred in the absence of any clear change in the index of aortic stiffness (PWVcf). Exercise-induced improvement in BP, both peripherally and centrally, indicates a decrease in total resistance to blood-flow rather than a decrease in resting cardiac output. Physiological mechanisms underlying exercise training-induced BP improvements appear to include improved endothelial function in conduit and resistance vessels, decreased oxidative stress, and improved autonomic regulation [26]. Positive endothelial adaptations to HIIT could plausibly be attributed to the greater vascular shear stress to endothelial cells induced by the intensity of the exercise.

A key finding from this study was the strong negative correlation between magnitude of reduction in BP following training and baseline BP levels, with the correlation being stronger in HIIT than in MICT. Further investigation is warranted and large-scale HIIT studies involving individuals with hypertension appear necessary to determine the optimal exercise training characteristics for improving BP. Preliminary evidence that HIIT is relatively safe for very-high cardiovascular-risk populations such as patients with coronary artery disease and heart failure when supervised, stringently-designed protocols are applied [27] suggest that HIIT may also be suitable for hypertensive but otherwise healthy individuals in a controlled setting. Further exercise ‘dose-response’ research for BP management could explore the modifying effects of various exercise modalities (e.g. cycling; running; swimming); HIIT variants such as maximal-effort, very short-duration sprint interval training (often termed SIT) or longer-duration intervals as applied in the popular Scandinavian HIIT model (4 × 4 min intervals with 3 min recovery intervals); and longer training periods.

We also aimed to explore the post-exertional hypotension (PEH) phenomenon that has been well-described previously [22, 28, 29], relating to the lowered BP (below resting levels) in the minutes and even hours following aerobic exercise. However, we did not observe any clear PEH effect of moderate-intensity or high-intensity cycling exercise when measured 10 min following sessions. This was a surprising finding considering the reasonably consistent evidence of PEH after aerobic exercise and is an ‘expected’ physiological response to exercise [22]. It is plausible that the application of only a single post-exercise assessment time-point and performed relatively soon after cessation of exercise (10 min post-exercise) was not sufficient to detect change in BP. Multiple post-exercise assessment time-points appear to be required to adequately explore the PEH phenomenon. The PEH phenomenon is worth exploring further, considering that preliminary evidence suggests that the magnitude of PEH following exercise sessions correlates strongly with the magnitude of change in BP observed following exercise training (r = 0.66–0.89 for SBP from recent studies [30,31,32]) and therefore chronic BP change following training may be an extension of the acute PEH phenomenon becoming a sustained response [22].

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study are the analysis of both acute and chronic effects of exercise on BP, with measures of both peripheral and central BP and arterial stiffness. Training sessions were closely supervised, and HIIT and MICT interventions were matched for total work. Interpretations of the findings should be made in the context of the relatively small sample sizes, the relatively short training period (6 weeks × 3 sessions/week) and the absence of a non-exercising control group. The all-male sample also limits the generalisability of the findings—there is some evidence to suggest that exercise-training-induced BP reductions are larger in males than in females [23]. Participant’s diet and daily physical activity patterns outside of the training sessions also were not controlled. Data regarding the effect of the exercise training on body composition and aerobic fitness measures will be detailed in a complementary publication.

Implications

There is currently no international consensus with regard to optimal exercise training characteristics for treating hypertension—while some regulatory bodies including the Japanese Society of Hypertension, the European Society of Hypertension and the American College of Sports Medicine recommend purely moderate-intensity exercise [33,34,35], others bodies such as the American Heart Association recommend moderate to vigorous intensity [24, 36, 37] (see Pescatello for a comprehensive review [38]). Considering HIIT is more time-effective than MICT and has robust evidence of efficacy for improving other cardiovascular-related indices such as aerobic fitness and body composition in both healthy and chronic illness populations [6,7,8,9], these findings do further support the case for HIIT to be considered as a treatment option for BP management.

Conclusion

HIIT decreased BP by ~3–5 mmHg in males with overweight or obesity. The magnitude of change in BP after exercise training was similar for both central (aortic) and peripheral (brachial) measures and occurred in the absence of change in aortic stiffness. The magnitude of change in BP after exercise training was strongly correlated with baseline BP levels, with these observed correlations stronger in HIIT than in MICT. HIIT could be a time-efficient intervention for BP management.

Summary

What’s already known about this topic

-

Exercise training can reduce blood pressure (BP) in normotensive and hypertensive adults.

What does this study add

-

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) appears to be effective for reducing BP (~3–5 mmHg reductions following 6-weeks training) in patients with overweight or obesity, especially for those with higher baseline BP.

-

Exercise training can lower central (aortic) blood pressure.

References

Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–e528.

Olsen MH, Angell SY, Asma S, Boutouyrie P, Burger D, Chirinos JA, et al. A call to action and a lifecourse strategy to address the global burden of raised blood pressure on current and future generations: the Lancet Commission on hypertension. Lancet (Lond, Engl). 2016;388:2665–712.

Collaborators GRF. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet (Lond, Engl). 2018;392:1923–94.

Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134:441–50.

Naci H, Salcher-Konrad M, Dias S, Blum MR, Sahoo SA, Nunan D, et al. How does exercise treatment compare with antihypertensive medications? A network meta-analysis of 391 randomised controlled trials assessing exercise and medication effects on systolic blood pressure. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:859–69.

Wewege M, van den Berg R, Ward RE, Keech A. The effects of high-intensity interval training vs. moderate-intensity continuous training on body composition in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2017;18:635–46.

Liou K, Ho SY, Fildes J, Ooi SY. High intensity interval versus moderate intensity continuous training in patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis of physiological and clinical parameters. Heart Lung Circulation. 2016;25:166–74.

Ramos JS, Dalleck LC, Tjonna AE, Beetham KS, Coombes JS. The impact of high-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training on vascular function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2015;45:679–92.

Jelleyman C, Yates T, O’Donovan G, Gray LJ, King JA, Khunti K, et al. The effects of high-intensity interval training on glucose regulation and insulin resistance: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:942–61.

Costa EC, Hay JL, Kehler DS, Boreskie KF, Arora RC, Umpierre D, et al. Effects of high-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training on blood pressure in adults with pre- to established hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Sports Med (Auckl, NZ). 2018;48:2127–42.

McEniery CM, Cockcroft JR, Roman MJ, Franklin SS, Wilkinson IB. Central blood pressure: current evidence and clinical importance. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1719–25.

Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kizer JR, Lee ET, Galloway JM, Ali T, et al. Central pressure more strongly relates to vascular disease and outcome than does brachial pressure: the Strong Heart Study. Hypertension. 2007;50:197–203.

Williams B, Lacy PS. Central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes. J Hypertens. 2009;27:1123–5.

Wang KL, Cheng HM, Chuang SY, Spurgeon HA, Ting CT, Lakatta EG, et al. Central or peripheral systolic or pulse pressure: which best relates to target organs and future mortality? J Hypertens. 2009;27:461–7.

Kollias A, Lagou S, Zeniodi ME, Boubouchairopoulou N, Stergiou GS. Association of central versus brachial blood pressure with target-organ damage: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex: 1979). 2016;67:183–90.

Williams B, Lacy PS, Thom SM, Cruickshank K, Stanton A, Collier D, et al. Differential impact of blood pressure-lowering drugs on central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes: principal results of the Conduit Artery Function Evaluation (CAFE) study. Circulation. 2006;113:1213–25.

Asmar RG, London GM, O’Rourke ME, Safar ME. Improvement in blood pressure, arterial stiffness and wave reflections with a very-low-dose perindopril/indapamide combination in hypertensive patient: a comparison with atenolol. Hypertension. 2001;38:922–6.

Hakansson S, Jones MD, Ristov M, Marcos L, Clark T, Ram A, et al. Intensity-dependent effects of aerobic training on pressure pain threshold in overweight men: a randomized trial. Eur J Pain. 2018;22:1813–23.

Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, et al. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2588–605.

Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:377–81.

Cohen, JW. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edn. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

MacDonald HV, Pescatello LS. Exercise and blood pressure control in hypertension. In: Kokkinos P, Narayan P, editors. Cardiorespiratory fitness in cardiometabolic diseases: prevention and management in clinical practice. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. 137–68.

Cornelissen VA, Smart NA. Exercise training for blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e004473.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13–e115.

Víctor Hugo A-S, Yuri F, Fredy Alonso P-V, Astrid Viviana V-R, Elkin Fernando A-V. Effects of high-intensity interval training compared to moderate-intensity continuous training on maximal oxygen consumption and blood pressure in healthy men: a randomized controlled trial. Biomedica. 2019;39:524–36.

Millar PJ, McGowan CL, Cornelissen VA, Araujo CG, Swaine IL. Evidence for the role of isometric exercise training in reducing blood pressure: potential mechanisms and future directions. Sports Med. 2014;44:345–56.

Wewege MA, Ahn D, Yu J, Liou K, Keech A. High-intensity interval training for patients with cardiovascular disease-is it safe? a systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009305.

Carpio-Rivera E, Moncada-Jiménez J, Salazar-Rojas W, Solera-Herrera A. Acute effects of exercise on blood pressure: a meta-analytic investigation. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia. 2016;106:422–33.

Angadi SS, Bhammar DM, Gaesser GA. Postexercise hypotension after continuous, aerobic interval, and sprint interval exercise. J Strength Conditioning Res. 2015;29:2888–93.

Wegmann M, Hecksteden A, Poppendieck W, Steffen A, Kraushaar J, Morsch A, et al. Postexercise hypotension as a predictor for long-term training-induced blood pressure reduction: a large-scale randomized controlled trial. Clin J Sport Med. 2018;28:509–15.

Hecksteden A, Grutters T, Meyer T. Association between postexercise hypotension and long-term training-induced blood pressure reduction: a pilot study. Clin J Sport Med. 2013;23:58–63.

Liu S, Goodman J, Nolan R, Lacombe S, Thomas SG. Blood pressure responses to acute and chronic exercise are related in prehypertension. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:1644–52.

Pescatello LS, Franklin BA, Fagard R, Farquhar WB, Kelley GA, Ray CA. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and hypertension. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:533–53.

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Bohm M, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–219.

Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, Asayama K, Dohi Y, Hirooka Y, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertension Res. 2019;42:1235–481.

Sharman JE, Stowasser M. Australian association for exercise and sports science position statement on exercise and hypertension. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12:252–7.

James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:507–20.

Pescatello LS. Exercise measures up to medication as antihypertensive therapy: its value has long been underestimated. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:849–52.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TC, RM, SH, MR, LM, AR, AF, CM and LC recruited participants and collected study data. TC, RM, MJ and AK analysed and interpreted the study data. TC, RM and AK wrote the manuscript. AK and RW designed the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clark, T., Morey, R., Jones, M.D. et al. High-intensity interval training for reducing blood pressure: a randomized trial vs. moderate-intensity continuous training in males with overweight or obesity. Hypertens Res 43, 396–403 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0392-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0392-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Impact of high-intensity interval training on cardiometabolic health in patients with diabesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome (2025)

-

Annual reports on hypertension research 2020

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

Post-exercise hypotension time-course is influenced by exercise intensity: a randomised trial comparing moderate-intensity, high-intensity, and sprint exercise

Journal of Human Hypertension (2021)

-

The impact of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) on arterial stiffness and blood pressure in young obese women: a randomized controlled trial

Hypertension Research (2020)