Abstract

Conventional office blood pressure (OBP) and home blood pressure (HBP) measurements are often inconsistent. The purpose of this research was (1) to test whether strictly measured OBP values with sufficient rest time before measurement (st-OBP) is comparable to HBP at the population level and (2) to ascertain whether there are particular determinants for the difference between HBP and st-OBP at the individual level. Data from a population-based group of 1056 men aged 40–79 years were analyzed. After a five-min rest, st-OBP was measured twice. HBP was measured after a 2-min rest every morning for seven consecutive days. To determine factors related to ΔSBP (HBP minus st-OBP measurements), multiple linear regression analyses and analyses of covariance were performed. While st-OBP and HBP were comparable (136.5 vs. 137.2 mmHg) at the population level, ΔSBP varied with a standard deviation of 13.5 mmHg. Smoking was associated with a larger ΔSBP regardless of antihypertensive usage, and BMI was associated with a larger ΔSBP in participants using antihypertensive drugs. The adjusted mean ΔSBP in the highest BMI tertile category was 4.6 mmHg in participants taking antihypertensive drugs. st-OBP and HBP measurements were comparable at the population level, although the distribution of ΔSBP was considerably broad. Smokers and obese men taking antihypertensive drugs had higher HBP than st-OBP, indicating that their blood pressure levels are at risk of being underestimated. Therefore, this group would benefit from the addition of HBP measurements.

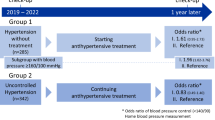

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is one of the major risk factors for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Accurate measurement of blood pressure (BP) is important to detect hypertension, but inappropriate measurement techniques are common [1]. Conventional office blood pressure (c-OBP), home blood pressure (HBP), and ambulatory blood pressure (ABP) are all standard methods of measuring BP, but there is often a discrepancy in their measurement values [2, 3]. Compared to c-OBP, HBP and ABP measurements are better predictors of CVD events [4,5,6,7]. Compared to treatments based on c-OBP measurements, treatments based on HBP measurements were significantly associated with a larger reduction in SBP [8].

While ABP can measure night-time BP, which predicts cardiovascular events independently from c-OBP [9], it requires frequent measurements every 20 or 30 min for 24 h, which is intrusive to daily living. Compared to ABP, HBP measurement is more practical [3], and it may avoid the clinical effect that occurs when BP is measured outside of a relaxing environment such as one’s home [10].

c-OBP measurements, performed in standard clinical situations, have been shown to be higher than HBP measurements [11,12,13]. On the other hand, at the population level, strictly measured office blood pressure (st-OBP) values with sufficient rest time before measurement (st-OBP) have been reported to be comparable to HBP measurements [14, 15]. Even if the mean values agree with each other at the population level, st-OBP measurements may not always be able to substitute for HBP measurements at the individual level because there could be a group with higher or lower HBP than st-OBP. It is important to clarify the characteristics of a group with higher HBP than st-OBP because relying on st-OBP measurements instead of HBP measurements can underestimate their actual BP levels and their risk of CVD outcomes.

The purpose of this research is (1) to test whether st-OBP is comparable to HBP at the population level and (2) to ascertain whether there are particular determinants for the difference between HBP and st-OBP at the individual level.

Methods

Study population

The Shiga Epidemiological Study of Subclinical Atherosclerosis (SESSA) is based on a community-based sample of Japanese residents [16,17,18] and was conducted between 2006 and 2008. We examined 1094 Japanese men aged 40–79 years who lived in Kusatsu City, Shiga, Japan. Candidates were identified on the basis of a random sample from the Kusatsu City Basic Residents’ Register, which includes the name, age, and sex of all city residents. We excluded 38 participants with missing or inappropriate HBP measurements, such as those measured only once in seven days or measured in the afternoon or those who did not complete the questionnaire. Thus, a total of 1056 participants comprised the analytic sample for this report. All participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shiga University of Medical Science in Otsu, Japan.

Blood pressure measurement

Strictly measured office blood pressure (st-OBP)

The participants’ st-OBP was measured as follows [17]. Participants were asked to fast for at least 12 h and to refrain from vigorous exercise after waking up in the morning. The participants were to have refrained from smoking for more than 30 min before the visit to the epidemiology clinic, which occurred between 9 am and 10 am. After urine sample collection, each participant sat in a chair in a quiet room. A trained nurse wrapped an appropriately sized cuff of a stationary-type automated device (BP-8800SF, Omron Healthcare Co. Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) [19] around the participant’s right upper arm and left the participant unattended during the following 5-min rest time. The 5-min rest was in a sitting position, without the participant crossing their legs or carrying on any conversation. The nurse returned to the participant and performed the st-OBP measurement without any conversation with the participant. st-OBP was measured twice consecutively by the nurse with an interval of 30 s. We used the mean value of the two measurements as the st-OBP. The pulse rate was automatically measured along with the BP.

Home blood pressure (HBP)

The participants were also asked to measure HBP using a portable automated device from the same manufacturer as the st-OBP measurement device (HEM-705 IT Fuzzy Cuff, Omron Healthcare Co. Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) [20] once every morning during the seven consecutive days after the clinic visit [17]. The instructions for measuring HBP with the device were given to each participant on the same day as the st-OBP measurements. They were instructed to measure HBP after urination, before breakfast, and before taking antihypertensive drugs, if relevant. They measured HBP in a seated position after a 2-min rest time within an hour after waking up. The measurement procedure corresponded to the recommendations of the Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension 2004 [21], and it also satisfied the newest Guideline issued in 2019 [22]. We used the mean HBP value of all measurements for each participant’s HBP.

Physical measurements and self-administered questionnaire

Body weight and height were measured while the participant was wearing light clothing without shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight (kg) divided by height in meters squared (m2). A self-administered questionnaire was used to obtain information on smoking habits, alcohol intake, medication use, and the frequency of physical activity in their leisure time. Trained research nurses reviewed these questionnaires. Smoking status was categorized as nonsmoker, ex-smoker, or current smoker, along with information about the number of cigarettes smoked per day. The amount of alcohol intake was calculated as ethanol intake (g/day) with the self-administered questionnaire, which asked the participants the kind of alcohol beverages, the amount, and the frequency of their drinking. The frequency of physical activity in leisure time was chosen from “often,” “sometimes,” or “seldom or never” in the self-administered questionnaire.

Blood specimens were obtained for lipid and glucose concentration measurements after a 12-h fast. These assessments are described elsewhere in detail [16,17,18].

Statistical methods

We calculated the difference in systolic blood pressure (ΔSBP) as HBP minus st-OBP for each participant. At the population level, the continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviations (SDs) for all participants and separately for those taking and not taking antihypertensive drugs. st-OBP and HBP at the population level were compared by unpaired t-tests. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the correlation between st-OBP and HBP. Bland–Altman plots [23], showing the mean values of st-OBP and HBP versus the difference between the two values, were used to assess the mean difference, the upper and lower limits of agreement (mean difference ± 1.96 ∗ standard deviation) between st-OBP and HBP, and the difference between the upper limit and the lower limit of agreement (defined as the 95% limit of the difference).

To examine the discrepancies between st-OBP and HBP measurements at an individual level, ΔSBP was examined by paired t-tests. To determine factors related to ΔSBP, multiple linear regression analyses were performed, with ΔSBP as the dependent variable and age, smoking status (non/ex-smokers, current smokers with ≤20 cigarettes day, and smokers with ≥21 cigarettes per day), BMI, alcohol intake (g/day), and the frequency of physical activity in leisure time as independent variables, stratifying the data for antihypertensive drug usage. Significantly related dependent variables in the above analyses were then categorized into three groups for analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) to further examine the relationship between the significant factors and ΔSBP, adjusting for other factors. Trend tests were performed for smoking status and BMI categories.

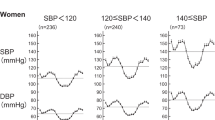

We performed a similar analysis for diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and for the difference in DBP (ΔDBP = HBP minus st-OBP).

Throughout the analyses, all tests were based on a two-sided significance level with α = 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS ver. 22 (IBM Corp., NY, USA).

Results

Among the analytic sample of 1056 participants, 953 (90.2%) measured HBP for seven consecutive days. The participants measured HBP an average of 6.8 ± 0.5 days.

At the population level, there was no significant difference between st-OBP and HBP. The mean SBP values of st-OBP vs. HBP (mmHg) were 136.5 vs. 137.2 in all participants (p = 0.134), 133.7 vs. 134.0 in participants not taking antihypertensive drugs (p = 0.624), and 142.5 vs. 143.8 in participants taking antihypertensive drugs (p = 0.076) (Table 1). HBP and st-OBP were strongly correlated (r = 0.74, p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The mean difference between HBP and st-OBP (HBP minus OBP) was 0.6 mmHg for ΔSBP (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The 95% limits of the differences between HBP and st-OBP ranged from −25.8 to 27.1 mmHg. In a post hoc analysis, abandoning the first-day HBP measurement in the analysis did not essentially alter the results.

At the individual level, however, while the mean ΔSBP was 0.6 mmHg, the distribution of ΔSBP was considerably broad, with an SD of 13.5 mmHg (Fig. 1). ΔSBP was 0.2 ± 12.8 in participants not taking antihypertensive drugs (p = 0.768) and 1.4 ± 14.9 in participants taking antihypertensive drugs (p = 0.641) (Table 1).

In multiple linear regression analyses (Table 2), in participants not taking antihypertensive drugs, smoking ≥21 cigarettes per day was associated with a larger ΔSBP than not smoking. In participants taking antihypertensive drugs, smoking was associated with a larger ΔSBP than not smoking regardless of the number of cigarettes consumed per day. Higher BMI was associated with a larger ΔSBP in participants taking antihypertensive drugs. Alcohol intake and physical activity level were not associated with ΔSBP.

Smoking status was divided into three groups to further examine with ANCOVA because smoking status was significantly associated with ΔSBP in the linear regression analyses. The adjusted mean ΔSBP was 4.8 mmHg for those who smoked ≥21 cigarettes daily without antihypertensive drug use. The adjusted means of ΔSBP in participants with antihypertensive drug use were 6.7 mmHg and 7.7 mmHg for smokers of ≤20 cigarettes daily and for smokers of ≥21 cigarettes daily, respectively. Significant trends were observed between smoking status and ΔSBP regardless of antihypertensive usage (Fig. 2). In post hoc analyses, ΔSBP was not significantly different between nonsmokers and ex-smokers; ΔSBP values of nonsmokers vs. ex-smokers in all participants, in those not taking antihypertensive drugs and in those taking antihypertensive drugs, were 0.02 vs. −0.56, 0.62 vs. −0.75, and −0.78 vs. 0.14 mmHg, respectively.

ΔSBP difference in systolic blood pressure (HBP minus st-OBP). An analysis of covariance was used to adjust for age, BMI, alcohol intake (g/day), and the frequency of physical activity in leisure time (“never or seldom,” “sometimes,” or “often”). Mean values are shown with standard errors. Levels of smoking were positively associated with ΔSBP regardless of antihypertensive usage

BMI was categorized into tertiles to further examine with ANCOVA because BMI was significantly associated with ΔSBP in the linear regression analysis. The adjusted mean ΔSBP in the highest BMI tertile (BMI of ≥24.7 kg/m2) was 4.6 mmHg in participants taking antihypertensive drugs. Significant trends were observed in participants taking antihypertensive drugs (p = 0.002) but not in participants not taking antihypertensive drugs (Fig. 3).

BMI body mass index, ΔSBP difference in systolic blood pressure (HBP minus st-OBP). An analysis of covariance was used to adjust for age, smoking status (nonsmokers, current smokers with 20 cigarettes or less per day, or smokers with ≥21 cigarettes per day), alcohol intake (g/day), and the frequency of physical activity in leisure time (“never or seldom,” “sometimes,” or “often”). Mean values are shown with error bars representing standard error. The highest tertile of BMI had the largest ΔSBP in participants taking antihypertensive drugs

Regarding DBP, the results were qualitatively similar to those of SBP (Supplementary Figs. 2–5 and Supplementary Table). The mean value of ΔDBP was 0.9 mmHg ± 7.9 mmHg (Supplementary Fig. 3). The associations between ΔDBP and smoking status were significant regardless of antihypertensive usage (Supplementary Fig. 4). The associations between ΔDBP and BMI levels were significant when analyzing all participants (Supplementary Fig. 5).

When the analyses were restricted to participants with fully adequate HBP measurements for seven consecutive days (N = 953, 90.2%), the results did not considerably change (data not shown).

Discussion

st-OBP was comparable to HBP at the population level (136.5 vs. 137.2 mmHg), but the difference between those measurements varied considerably at the individual level. The standard deviation of ΔSBP exceeded 13 mmHg. Smoking and BMI were positively related to ΔSBP. Age was negatively related to ΔSBP with borderline significance in participants not taking antihypertensive drugs (p = 0.066). To our knowledge, this is the first report revealing the factors affecting the difference between HBP and OBP with a sufficient rest time before measurement in a general population.

Our results showed that st-OBP was comparable to HBP at the population level. This issue of comparing HBP with OBP measurements has been controversial; c-OBP has been reported to be higher than HBP in other studies [24, 25]. The 2017 AHA hypertension guideline states that c-OBP is higher than HBP only in patients with SBP measured in clinics at 130 mmHg or higher [3]. On the other hand, measurements of st-OBP, taking sufficient rest time before measurement, have been reported to be comparable to measurements of HBP in patients at general clinics [14, 15]. Our results support the latter notion in a random sample of men in a general population. Our results suggest that st-OBP with sufficient rest before BP measurement will be comparable to HBP at the population level, whereas c-OBP measurements in most clinical settings and annual health screenings will not be comparable to HBP measurements. Our results revealed a higher correlation between HBP and st-OBP (R = 0.74 for SBP) than reported in previous studies [14, 15], possibly because our measurements were limited to the morning, whereas the OBP measurements in previous studies were performed throughout the day.

At the individual level, however, ΔSBP varied with a standard deviation of 13.5 mmHg. This suggests that st-OBP values can be very different from HBP values obtained from the same person. The factors associated with a larger ΔSBP were smoking for all participants and higher BMI in participants taking antihypertensive drugs. Previous reports on this topic exist [24, 25], but the c-OBP values did not agree with the HBP values at the population level, suggesting that these c-OBP measurements cannot be regarded as st-OBP measurements. We believe that our findings are important to prevent the underestimation of BP levels by using only st-OBP measurements because subjects who smoke or hypertensive patients with high BMI may actually have higher HBP than an apparently normal st-OBP.

Regarding factors related to lower ΔSBP, age in participants not taking antihypertensive drugs was borderline significant (p = 0.066). This was comparable with a previous report that younger age was related to lower c-OBP than HBP [24] in a general population.

Smoking status was positively associated with higher HBP than st-OBP regardless of antihypertensive drug usage. Smoking stimulates the adrenergic nervous system and elevates plasma catecholamines to increase BP [26]. Smoking one cigarette raises BP by ~10/8 mmHg in SBP/DBP, and that rise effect lasts for 15 min. Thereafter, the BP slowly decreases over several hours [27]. We did not determine whether participants smoked before measuring HBP in the morning after they woke up. Therefore, some subjects may have smoked before measuring HBP, making their HBP higher than their st-OBP due to the temporal effects of smoking. Nevertheless, our participants smoked an average of 20 cigarettes per day, suggesting that smokers frequently face a temporary rise in BP, resulting in the same situation as primary hypertensive patients. Our results suggest that current smokers in particular would benefit from HBP measurement because their OBP may be lower than their actual BP. In our post hoc analyses, we found no significant difference in ΔSBP between ex-smokers and never-smokers, which justifies our statistical procedure of combining ex-smokers and never-smokers as nonsmokers.

Higher BMI was associated with a higher HBP than st-OBP in participants taking antihypertensive drugs, suggesting that obese men taking hypertensive drugs have SBP levels that are higher than their st-OBP levels. This may reflect a more pronounced sympathetic neural overdrive in obese and overweight states [28] because the sympathetic nervous system is activated after awakening in the morning.

We measured st-OBP by having a trained nurse attending to each participant after a 5-min unattended rest time, which may suggest that the return of the nurse and/or the presence of the nurse during st-OBP measurement caused a “white coat effect.” [10] However, our results actually suggest that there was little influence of the presence of the nurse in that the mean ΔSBP for each participant was 0.6 mmHg, whereas a hypothetical “white coat effect” should cause a mean ΔSBP of less than zero. In addition, a publication from SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) revealed that the presence of a staff member after a 5-min unattended rest time resulted in a nonsignificant difference of 0.4 mmHg or less in SBP measurement [29]. We believe that our st-OBP measurement procedure was not affected by a “white coat effect.”

The strengths of our study are that this population was a random sample of a wide range of age groups and that the st-OBP was measured with a sufficient rest period before BP measurements, resulting in good agreement between HBP and st-OBP at a population level.

The limitations of our study are as follows. First, our study cohort was composed of only Japanese men; thus, our findings cannot be generalized to women or to other ethnicities. Second, we measured HBP only once a day to maximize the feasibility for the participants to complete the seven days of HBP measurements, and we did not confirm in what part of the day antihypertensive drugs were taken, resulting in a failure to ascertain the effects of antihypertensive drug timing on ΔSBP. Third, the two BPs (st-OBP and HBP) were measured with different devices, although they were both validated products from the same manufacturer. Finally, there may be some other potential factors that we did not investigate, such as nutritional factors such as sodium intake.

In conclusion, values of OBP with a sufficient rest time before measurement were comparable to values of HBP at the population level. However, at the individual level, the difference between the two measurements had a considerably broad distribution. Especially for all smokers and obese men taking hypertensive drugs, measured values of HBP were higher than those of OBP taken with a sufficient rest time before measurement. The measurement of both HBP and OBP with a sufficient rest time is important to avoid the underestimation of the actual BP levels.

References

Kallioinen N, Hill A, Horswill MS, Ward HE, Watson MO. Sources of inaccuracy in the measurement of adult patients’ resting blood pressure in clinical settings: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2017;35:421–41.

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315–81.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13–e115.

Sega R, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, Cesana G, Corrao G, Grassi G, et al. Prognostic value of ambulatory and home blood pressures compared with office blood pressure in the general population: follow-up results from the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate e Loro Associazioni (PAMELA) study. Circulation. 2005;111:1777–83.

Bliziotis IA, Destounis A, Stergiou GS. Home versus ambulatory and office blood pressure in predicting target organ damage in hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1289–99.

Stergiou GS, Siontis KC, Ioannidis JP. Home blood pressure as a cardiovascular outcome predictor: it’s time to take this method seriously. Hypertension. 2010;55:1301–3.

Ward AM, Takahashi O, Stevens R, Heneghan C. Home measurement of blood pressure and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Hypertens. 2012;30:449–56.

Satoh M, Maeda T, Hoshide S, Ohkubo T. Is antihypertensive treatment based on home blood pressure recommended rather than that based on office blood pressure in adults with essential hypertension? (meta-analysis). Hypertens Res. 2019;42:807–16.

Roush GC, Fagard RH, Salles GF, Pierdomenico SD, Reboldi G, Verdecchia P, et al. Prognostic impact from clinic, daytime, and night-time systolic blood pressure in nine cohorts of 13,844 patients with hypertension. J Hypertens. 2014;32:2332–40.

Asayama K, Ohkubo T. Unattended automated measurements: office and out-of-office blood pressures affected by medical staff and environment. Hypertension. 2019;74:1294–6.

Verberk WJ, Kroon AA, Kessels AG, de Leeuw PW. Home blood pressure measurement: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:743–51.

Yarows SA, Qian K. Accuracy of aneroid sphygmomanometers in clinical usage: University of Michigan experience. Blood Press Monit. 2001;6:101–6.

Niiranen TJ, Jula AM, Kantola IM, Reunanen A. Comparison of agreement between clinic and home-measured blood pressure in the Finnish population: the Finn-HOME Study. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1549–55.

Fagard RH, Van Den Broeke C, De Cort P. Prognostic significance of blood pressure measured in the office, at home and during ambulatory monitoring in older patients in general practice. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:801–7.

Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Rakugi H, Miyakawa M, Mori H, Katsuya T, et al. Comparison of blood pressure values-self-measured at home, measured at an unattended office, and measured at a conventional attended office. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1726–37.

Ueshima H, Kadowaki T, Hisamatsu T, Fujiyoshi A, Miura K, Ohkubo T, et al. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 is related to risk of subclinical atherosclerosis but is not supported by Mendelian randomization analysis in a general Japanese population. Atherosclerosis. 2016;246:141–7.

Satoh A, Arima H, Hozawa A, Ohkubo T, Hisamatsu T, Kadowaki S, et al. The association of home and accurately measured office blood pressure with coronary artery calcification among general Japanese men. J Hypertens. 2019;37:1676–81.

Shitara S, Fujiyoshi A, Hisamatsu T, Torii S, Suzuki S, Ito T, et al. Intracranial artery stenosis and its association with conventional risk factors in a general population of Japanese men. Stroke. 2019;50:2967–9.

Naschitz JE, Gaitini L, Loewenstein L, Keren D, Zuckerman E, Tamir A, et al. In-field validation of automatic blood pressure measuring devices. J Hum Hypertens. 2000;14:37–42.

Coleman A, Freeman P, Steel S, Shennan A. Validation of the Omron 705IT (HEM-759-E) oscillometric blood pressure monitoring device according to the British Hypertension Society protocol. Blood Press Monit. 2006;11:27–32.

Japanese Society of H. Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2004). Hypertens Res. 2006;29:S1–105.

Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, Asayama K, Dohi Y, Hirooka Y, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1235–481.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–10.

Hozawa A, Ohkubo T, Nagai K, Kikuya M, Matsubara M, Tsuji I, et al. Factors affecting the difference between screening and home blood pressure measurements: the Ohasama Study. J Hypertens. 2001;19:13–9.

Horikawa T, Obara T, Ohkubo T, Asayama K, Metoki H, Inoue R, et al. Difference between home and office blood pressures among treated hypertensive patients from the Japan Home versus Office Blood Pressure Measurement Evaluation (J-HOME) study. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:1115–23.

Grassi G, Seravalle G, Calhoun DA, Bolla G, Mancia G. Cigarette smoking and the adrenergic nervous system. Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1992;14:251–60.

Freestone S, Ramsay LE. Effect of coffee and cigarette smoking on the blood pressure of untreated and diuretic-treated hypertensive patients. Am J Med. 1982;73:348–53.

Grassi G, Biffi A, Seravalle G, Trevano FQ, Dell’Oro R, Corrao G, et al. Sympathetic neural overdrive in the obese and overweight state. Hypertension. 2019;74:349–58.

Johnson KC, Whelton PK, Cushman WC, Cutler JA, Evans GW, Snyder JK, et al. Blood pressure measurement in SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial). Hypertension. 2018;71:848–57.

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply indebted to participants and staff members of the SESSA. The members of the SESSA are listed in the Appendix.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research (A) 13307016, (A) 17209023, (A) 21249043, (A) 23249036, (A) 25253046, (A) 15H02528, (B) 18H03048, and (C) 19K10642 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan; by the National Institutes of Health in the USA [R01HL068200]; and by Glaxo-Smith Kline GB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

SESSA Research Group members and their affiliation details are listed in Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kadowaki, S., Kadowaki, T., Hozawa, A. et al. Differences between home blood pressure and strictly measured office blood pressure and their determinants in Japanese men. Hypertens Res 44, 80–87 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-00533-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-00533-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Annual reports on hypertension research 2020

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

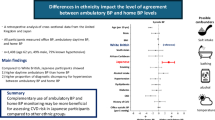

Home and office blood pressure: time to look at the individual patient

Hypertension Research (2021)