Abstract

Despite clear evidence of the benefits of lowering blood pressure among patients with hypertension, the treatment rate remains <40% worldwide. In the present trial, we aimed to investigate the effects of the early promotion of clinic visits among patients with untreated hypertension detected during annual health checkups. This was a worksite-based, parallel group, cluster-randomized trial with blinded outcome assessment. Employees of 152 Japanese supermarket stores found to have untreated hypertension (blood pressure levels ≥ 160/100 mmHg) during health checkups were assigned to an early promotion group (encouraged to visit a clinic in face-to-face interviews and provided with a referral letter to a physician as well as a leaflet) or a control group (received usual care), according to random assignment. The primary outcome was the completion of a clinic visit within 6 months. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for the early promotion group versus the control group were estimated using multilevel logistic regression with random effects of clusters. A total of 273 participants (mean age 50.3 years, 55% women) from 107 stores were assigned to the early promotion group (138 from 55 stores) or control group (135 from 52 stores). During the 6-month follow-up, 47 (34.1%) participants in the early promotion group visited a clinic, as did 26 (19.3%) in the control group (odds ratio 2.33, 95% confidence interval 1.12–4.84, P = 0.024). Early promotion using a referral letter during health checkups significantly increased the number of clinic visits within 6 months completed by participants with untreated hypertension (UMIN000025411).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is one of the most important modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD). Many clinical trials have clearly shown protective effects of blood pressure (BP)-lowering treatment against CVD, which appears to be mostly explained by a reduction in BP levels [1,2,3,4]. However, the treatment rate of hypertension remains under 40% worldwide [5, 6] and ~40% among Japanese people [7,8,9]. In the Japanese health care system, untreated hypertension is most frequently detected during annual health checkups [10, 11], and medical follow-up by community physicians is the first gateway to assess the need for BP-lowering medication. However, most of these individuals do not visit a clinic afterward [12]. Reducing the evidence–practice gap requires strategies to promote early clinic visits after the detection of untreated hypertension in health checkups. The aim of the present cluster-randomized trial was to investigate the effects of the early promotion of visits to a clinic among patients with untreated hypertension that was detected during health checkups.

Methods

Japanese health care system and setting

Under the universal coverage principal of 1961, all residents in Japan are required to enroll in a health insurance system, according to their occupation and ages. Employees’ health insurance is for salaried workers and their dependent family members. Beneficiaries may freely visit any approved hospital or clinic. Fees for medical services at all approved hospitals and clinics are strictly controlled by the national government and are paid on a fee-for-service basis. When a beneficiary uses a medical service, he or she pays 30% of the cost, whereas the insurer pays 70%. Information on medical fees and medical services must be recorded monthly in an insurance claim history file. There are very few physicians practicing outside the health insurance system, except in the area of normal delivery, preventive medicine, and cosmetic surgeries [13, 14].

Approximately 70% of Japanese adults had a regular health checkup in their community or worksite [15]. Many health checkups are provided by health care agencies. Every examinee receives a written report of results within a few months after the health checkup [16, 17]. Usually, physicians in charge of health checkups do not provide further medical examination and treatment. Therefore, patients are expected to visit clinics on their own if they recommend further medical examination or treatment.

The present study was conducted in a retail company with 152 supermarket stores located across nine prefectures in western Japan. All employees who work more than 6 h a day were covered by the same health insurance organization, and most of them had annual health checkups provided by health care agencies in their worksite.

Study design

This was a worksite-based, parallel group, cluster-randomized trial with blinded outcome assessment conducted in Japan. A total of 152 supermarket stores were randomly assigned to strategies aiming to promote clinic visits among untreated patients with hypertension, either using a referral letter provided on the day of the health checkup (early promotion) or with usual care (control). An independent statistician generated the randomized assignment sequence for the stores, which were stratified according to the number of employees with untreated hypertension (BP levels ≥ 160/100 mmHg identified at health checkups in 2016) as follows: ≤5, 6–19, 20–39, or ≥50 employees.

Participants

Participants were eligible if they were 20–65 years of age, underwent annual health checkups in both 2016 and 2017, and had untreated hypertension in 2017 (BP ≥ 160/100 mmHg and no use of BP-lowering medications) that persisted beginning in 2016 (BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg). We decided on the above inclusion criteria, with a BP ≥ 160/100 mmHg rather than a BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg, because the association between BP level and CVDs is graded and continuous, and participants need to be aware of the necessity of medications as soon as possible [9]. In addition, we invited patients with persistent hypertension beginning in 2016 to exclude transient hypertension. Participants were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (i) pregnancy in 2016 or 2017 or (ii) severe hypertension (BP ≥ 190/120 mmHg) in 2017 requiring immediate pharmacological intervention.

Eligible employees were invited to participate in the study, and written informed consent for data collection was obtained from all participants, who were blinded to the purpose of the study (i.e., to investigate the effect of early promotion of clinic visits). Participants in the present study were not provided any lifestyle interventions on diet, exercise, etc. in their workplace over the next year. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Shiga University of Medical Science (28–144). The study protocol was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000025411).

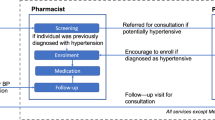

Interventions

The intervention of the present study was conducted by 19 medical staff trained using a standardized protocol. Eligible participants were invited to a small privacy-protected booth after BP measurement of the health checkup, and medical staff provided the intervention assigned to each supermarket store. For the early promotion group, the medical staff encouraged participants to visit clinics during a face-to-face interview session and then provided participants with a referral letter to a physician (which included the participant’s name, date of birth, BP, and results of his or her health checkup in the previous year) and a leaflet (explaining the importance of clinic visits and BP control for hypertensives in general terms). Similarly, for the control group, the medical staff encouraged a visit to a clinic using the leaflet, per usual practice. In short, the difference between the two groups was whether we performed early health promotion using a referral letter.

Procedures

The procedure for the annual health checkup provided at the worksites was the same in 2016, 2017, and 2018. Health checkups included self-administered questionnaires on health-related behaviors and medical histories, anthropometric measurements, BP measurements, blood tests, urinary tests, electrocardiography, and chest X-ray. Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Information about smoking habits (current smoker or not), alcohol consumption (daily drinker or not), and the use of antihypertensive agents were evaluated using self-administered questionnaires. BP was measured by trained nurses using an automatic sphygmomanometer with the oscillometric method and an appropriately sized cuff, with participants in a seated position after a 5 min rest. The sphygmomanometers used differed among stores; an Omron HBP-1300 [18] was used in 90 stores, an Omron HEM-907 [19] in 14 stores, and a Japan Colin BP-103iII in 3 stores. There was no difference in the type of sphygmomanometer used between the two randomized groups. If a participant’s BP was ≥140/90 mmHg, BP was measured twice, and the average value was used for the assessment of inclusion criteria and the statistical analyses. Prior to the blood tests, 80% of participants had not fasted. Plasma glucose was measured using the hexokinase method, and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was measured with the immunological method. Diabetes was defined as a fasting plasma glucose level ≥ 7.0 mmol/L and/or casual plasma glucose level ≥ 11.1 mmol/L and/or HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol and/or treatment for diabetes with antidiabetic agents or insulin.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the completion of a clinic visit for the assessment/management of hypertension within 6 months after the health checkup. This was assessed using the diagnosis of hypertension (10th International Classification of Disease [ICD-10] codes I10–I15) in medical insurance claims data. Secondary outcomes were the initiation of BP-lowering medication for hypertension within 6 months after the health checkup and BP levels after 1 year. Initiation of BP-lowering medication was defined as prescription of BP-lowering medication based on the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system using medical insurance claims data; in Japan, BP-lowering medication is available usually only in health insurance treatment. BP levels after 1 year were measured at the health checkup in 2018 with the same procedure used in the health checkups during 2017. All outcomes were defined using medical insurance claims data and health checkup data in 2018 by the health insurance organization in which all participants were covered. The study investigators were blinded to the information on claims data during the conduct of the trial.

Statistical analysis

We anticipated that 152 clusters (i.e., supermarket stores) would have more than 80% power (two-tailed α level of 0.05) to detect a relative 20% increase in the primary outcome (i.e., clinic visits within 6 months) in the early promotion group versus the control group (estimated rate of the primary outcome, 25%). This assumption was based on an average cluster size of 1.75 and an intracluster correlation of 0.1, according to data from participants who had completed health checkups in 2016, as well as conservative estimates of a 10% participant dropout rate owing to a job change or retirement.

To compare baseline characteristics between the two groups, we performed chi-square tests for dichotomous and categorical data and unpaired t tests for continuous data. The effects of the intervention on the primary outcome (completing a clinic visit within 6 months) and secondary outcome (initiation of BP-lowering medication within 6 months) were assessed using multilevel logistic regression with random effects of clusters (i.e., supermarket stores); odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated for the early promotion group versus the control group. We calculated the number needed for a referral letter for clinical visits (NNT). The effects of the intervention on the secondary outcome of BP levels after 1 year were assessed using a multilevel mixed model with random effects of clusters (i.e., supermarket stores), and the difference in mean values with 95% CIs between randomized groups was estimated. As a sensitivity analysis, we adjusted smoking status in model 1 because it was significantly different between groups. In model 2, we adjusted for other related factors.

All analyses were conducted using Stata 15 (Stata Corp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA). All P values were two tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Figure 1 shows the participant flow in this study. In total, 152 stores were randomized to the early promotion group (n = 76) or the control group (n = 76). For the baseline health checkups conducted from January to March 2017, a total 330 eligible employees with untreated hypertension were identified in 110 supermarket stores, and a total of 287 participants in 108 supermarket stores provided their consent to participate in the trial. The consent rates were 87.5% in the early promotion group and 86.5% in the control group. During the 6-month follow-up, 14 employees were lost to follow-up because of retirement or a job change; the remaining 273 participants (early promotion group: n = 138, control group: n = 135) were included in the statistical analysis. The average cluster size was 2.6 (range: 1–12). The baseline characteristics of supermarket stores by intervention group are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics by randomized group of all participants and those who could be followed up. The mean age (standard deviation) of the 287 participants was 50.6 (8.7) years, and 56.1% of participants were women. The mean systolic BP (standard deviation) was 164.1 (9.8) mmHg in the early promotion group and 164.7 (10.4) mmHg in the control group. The prevalence of current smokers was significantly higher in the control group (P = 0.029). There were no clear differences in the baseline characteristics of the participants (with and without follow-up) for each randomized group. Interventions were strictly performed according to the protocol. Referral letters to a physician were provided to all participants in the early promotion group only.

During the 6-month follow-up period, 73 (26.7%) of 273 participants visited a clinic for the assessment and/or treatment of hypertension. The intracluster correlation coefficient was 0.20. Table 2 shows the effects of the early promotion of clinic visits and secondary outcomes. With respect to primary outcome, a total of 47 (34.1%) participants in the early promotion group visited a clinic within 6 months, as did 26 (19.3%) participants in the control group (OR 2.33, 95% CI 1.12–4.84, P = 0.024). The NNT for clinical visits was 6.8. With regard to secondary outcomes, more participants initiated BP-lowering medication in the early promotion group (31 [22.5%]) than in the control group (22 [16.3%]), although the difference was not significant (OR 1.54, 95% CI 0.77–3.08, P = 0.226). No significant differences in systolic or diastolic BP were observed after 1 year between randomized groups (difference −0.3/−1.3 mmHg, 95% CI −4.4–3.9/−4.0–1.4, P = 0.905/0.352).

After adjustment were made for smoking status in the sensitivity analysis, the results did not change for clinic visits within 6 months (OR 2.32, 95% CI 1.11–4.86, P = 0.025). The results also did not change when we adjusted for other factors related to outcomes (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the effect of early health promotion using a referral letter to increase clinic visits among patients with untreated hypertension. The completion rate of clinic visits within 6 months was significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group. Our main result suggested the importance of early health promotion for detected hypertension, especially in Japanese health situations in which medical follow-up by community physicians is the first gateway to assess the need for BP-lowering medication, which is usually available only through treatment provided by health insurance. On the other hand, for the secondary outcomes, the initiation of BP-lowering medication within 6 months or BP levels after 1 year were not different between the groups.

Previous studies have investigated the effects of referral to a community physician in improving clinical follow-up or lowering BP among participants in the workplace [20], community [21, 22], and emergency departments [23]. A randomized controlled study of 74 patients with elevated diastolic BP (between 95 and 120 mmHg) detected among military veterans at a walk-in screening clinic found that participants who were sent referral letters to their home contacted their local physician more frequently than did those who were not sent a referral letter (63% [22/35] vs. 33% [13/39], P = 0.012) [21]. A community-based randomized controlled trial among patients with hypertension aged 18 years or over in Seattle also found a higher rate of medical follow-up in the intervention group (referrals with enhanced tracking) than in the control group receiving usual care (65.1% [95/146] vs. 46.7% [77/165], P = 0.001; NNT = 5) [22]. In Japan, the effect of referrals on clinical follow-up among patients with hypertension has not previously been thoroughly evaluated [24]. We cannot simply compare our findings with those of previous Western studies because the effect of referrals may depend on health settings such as the hypertension treatment rate, the characteristics of participants, and the health care system. However, the results of the present study were consistent with those of previous findings. Providing individuals with a referral letter clearly indicates the desired behavior (i.e., visiting a clinic) versus the use of an educational leaflet alone. An important point is that we provided participants with a referral letter on the day of the health checkup. Timely health promotion strongly emphasizes the importance of clinic visits. In terms of feasibility, the health promotion intervention in our study is practical during general health checkups in Japan, many of which are provided by health checkup agencies [16]. The intervention procedure described herein does not require a large number of staff and takes only ~5 min per person.

In the present study, the completion rate of clinic visits was lower than that in previous Western studies, although all participants were covered by the same health insurance organization and could use medical services with 30% medical cost. A recent Japanese observational study that included 17,173 insured patients with hypertension (15,793 men and 1380 women) aged 20–68 years (possible hypertension was defined using a cutoff of 140/90 mmHg) also reported a low rate of clinical follow-up; only 10.3% of men with hypertension and 17.7% of women visited clinics within 6 months after their health checkup [12]. However, in population-based Japanese nationwide cancer screening programs, 70–80% of individuals are followed up, depending on the type of cancer [25]. We must understand the specific barriers to clinic visits among asymptomatic hypertensive patients, such as denial of or careless or hopeless attitudes regarding hypertension [26, 27], to best target efforts to reduce untreated hypertension.

In the analysis of secondary outcomes, the initiation of BP-lowering medication was not significantly different between the two groups; the medication rate in the early promotion group remained at 66% of patients who visited a clinic. In the present study, we could not determine the reason why the medication rate was lower in the early promotion group; however, the recently introduced concept of clinical inertia might be important [28, 29]. Patients in whom hypertension is detected at a health checkup may not sufficiently understand the benefits of BP-lowering medication, and such patient-related factors may influence the initiation of medication prescribed by a physician [30]. In our analysis of BP at 1 year after the intervention, the mean BP of participants was still high in both groups, and we did not find any differences between the groups, although clinically relevant outcome parameters were important. This may be because of the small number of participants who initiated medication. Even if BP was decreased in treated patients, this may not have affected the mean BP of all participants in both groups. Future studies are required to examine the improvement in BP with sufficient numbers of subjects. At the same time, to control hypertension that is detected in health checkups, we need to make further efforts to determine whether BP-lowering medication was initiated appropriately after clinic visits and to reduce barriers to clinic visits among those who did not respond to early health promotion. Additionally, comprehensive health intervention is very important, as is a referral to a community physician [31].

We should note the following limitations of our study. First, we could not deny the possibility that a certain proportion of participants had not been assigned the disease name of hypertension (including suspected hypertension) in the health insurance claim by a physician (or a medical clerk) if their home BP and/or clinic BP levels were lower than the diagnostic thresholds recommended in the guidelines [7, 9, 32, 33] because office BP measurements were included in the initial visit fee. If the rate of clinic visits was higher, the NNT was expected to be smaller than our calculation. Second, the methods for BP measurement were not strictly controlled. We defined untreated patients with hypertension based on BP measured on a single day during a general health checkup conducted in the winter (between January and March). Some participants may not have visited a clinic because their office BP may have been higher owing to white coat hypertension or seasonal fluctuations [34, 35]. Verification of our findings using home or ambulatory BP is required [32]. However, our results are important from the perspective of real-world applicability. Third, some supermarket stores had no eligible patients because of the cluster size. Thus, there is a possibility that there was an imbalance of participant characteristics between the assigned groups. To address the imbalance observed to be statistically significant for smoking status and to confirm the effects of other variables, we conducted multivariable-adjusted models as a sensitivity analysis and obtained comparable findings. Fourth, participants were limited to the employees of a Japanese retail company. It is necessary to use caution when generalizing the results.

Despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomized trial seeking to increase clinic visits for the assessment and management of hypertension detected during a general health checkup. The findings of this study will contribute to reducing untreated hypertension worldwide and to advancing the “Data Health Plans” proposed by the Japanese government for each medical insurance organization beginning in 2015 [36], aiming to improve the treatment rate of hypertension.

In the present study, a site-based cluster-randomized controlled trial conducted in a Japanese population, the early promotion of clinic visits using face-to-face interviews and referral letters to a physician during annual health checkups significantly increased the number of clinic visits completed within 6 months by participants with untreated hypertension.

References

Staessen JA, Wang JG, Thijs L. Cardiovascular prevention and blood pressure reduction: a quantitative overview updated until 1 March 2003. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1055–76. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004872-200306000-00002.

Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration, Turnbull F, Neal B, Pfeffer M, Kostis J, Algert C, et al. Blood pressure-dependent and independent effects of agents that inhibit the renin-angiotensin system. J Hypertens. 2007;25:951–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280bad9b4.

Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009;338:1245. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b1665.

Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, Anderson SG, Callender T, Emberson J, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:957–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01225-8.

Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control. Circulation. 2016;134:441–50. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912.

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Long-term and recent trends in hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in 12 high-income countries: an analysis of 123 nationally representative surveys. Lancet. 2019;394:639–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31145-6.

The Japanese Society of Hypertension. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2019). Tokyo, Japan: Life Science Publishing Co., Ltd.; 2019.

Satoh A, Arima H, Ohkubo T, Nishi N, Okuda N, Ae R, et al. NIPPON DATA2010 Research Group. Associations of socioeconomic status with prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in a general Japanese population. J Hypertens. 2017;35:401–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000001169.

Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, Asayama K, Dohi Y, Hirooka Y, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1235–481.

Turin TC, Murakami Y, Miura K, Rumana N, Kita Y, Hayakawa T, et al. NIPPON DATA80/90 Research Group. Hypertension and life expectancy among Japanese: NIPPON DATA80. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:954–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2012.86.

Kobayashi A. Launch of a national mandatory chronic disease prevention program in Japan. Dis Manag Heal Outcomes. 2008;16:217–25. https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200816040-00003.

Kuriyama A, Takahashi Y, Tsujimura Y, Miyazaki K, Satoh T, Ikeda S, et al. Predicting failure to follow-up screened high blood pressure in Japan: a cohort study. J Public Health. 2015;37:498–505. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdu056.

Ikegami N. Should providers be allowed to extra bill for uncovered services? Debate, resolution, and sequel in Japan. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2006;31:1129–49. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-2006-022.

Ikegami N, Yoo BK, Hashimoto H, Matsumoto M, Ogata H, Babazono A, et al. Japanese universal health coverage: evolution, achievements, and challenges. Lancet. 2011;378:1106–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60828-3.

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions in Japan, 2016.2017. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa16/. Accessed 9 March 2020.

Hino Y, Kan H, Minami M, Takada M, Shimokubo N, Nagata T, et al. The challenges of occupational health service centers in Japan. Ind Health. 2006;44:140–3. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.44.140.

Suka M, Odajima T, Okamoto M, Sumitani M, Nakayama T, Sugimori H. Reading comprehension of health checkup reports and health literacy in Japanese people. Environ Health Prev Med. 2014;19:295–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12199-014-0392-8.

Meng L, Zhao D, Pan Y, Ding W, Wei Q, Li H, et al. Validation of Omron HBP-1300 professional blood pressure monitor based on auscultation in children and adults. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-015-0177-z.

White WB, Anwar YA. Evaluation of the overall efficacy of the Omron office digital blood pressure HEM-907 monitor in adults. Blood Press Monit. 2001;6:107–10.

Erfurt JC, Foote A, Heirich MA. Worksite wellness programs: incremental comparison of screening and referral alone, health education, follow-up counseling, and plant organization. Am J Health Promot. 1991;5:438–48. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-5.6.438.

Velez R, Anderson L, McFall S, Magruder-Habib K. Improving patient follow-up in incidental screening through referral letters. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:2184–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1985.00360120052008.

Krieger J, Collier C, Song L, Martin D. Linking community-based blood pressure measurement to clinical care: a randomized controlled trial of outreach and tracking by community health workers. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:856–61. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.89.6.856.

Jones PK, Jones SL, Katz J. Improving follow-up among hypertensive patients using a health belief model intervention. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1557–60. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1987.00370090037007.

Hanai Y, Tabuse Y, Nishikawa A, Aiba O, Tsuboi M, Tsuchiya E, et al. Increase in examination rate for secondary testing due to improved guidance and future issues. Ningen Dock. 2017;32:2012–7.

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Report on regional public health services and health promotion services. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/c-hoken/17/dl/gaikyo.pdf. 2017. Accessed 9 Mar 2020.

Goldbeck R. Denial in physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1997;43:575–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00168-2.

Jokisalo E, Kumpusalo E, Enlund H, Takala J. Patients’ perceived problems with hypertension and attitudes towards medical treatment. J Hum Hypertens. 2001;15:755–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1001276.

Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, Doyle JP, El-Kebbi IM, Gallina DL, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:825–34. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012.

Josiah Willock R, Miller JB, Mohyi M, Abuzaanona A, Muminovic M, Levy PD. Therapeutic inertia and treatment intensification. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20:4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-018-0802-1.

Harle CA, Harman JS, Yang S. Physician and patient characteristics associated with clinical inertia in blood pressure control. J Clin Hypertens. 2013;15:820–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.12179.

Wang Z, Wang X, Shen Y, Li S, Chen Z, Zheng C, et al. China Hypertension Survey Group: The Standardized Management of Hypertensive Employees Program. Effect of a workplace-based multicomponent intervention on hypertension control: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2020:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2019.6161.

Ohkubo T, Imai Y, Tsuji I, Nagai K, Kato J, Kikuchi N, et al. Home blood pressure measurement has a stronger predictive power for mortality than does screening blood pressure measurement: a population-based observation in Ohasama, Japan. J Hypertens. 1998;16:971–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004872-199816070-00010.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2018;12:579.e1–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jash.2018.06.010.

Mori H, Ukai H, Yamamoto H, Saitou S, Hirao K, Yamauchi M, et al. Current status of antihypertensive prescription and associated blood pressure control in Japan. Hypertens Res. 2006;29:143–51. https://doi.org/10.1291/hypres.29.143.

Hozawa A, Kuriyama S, Shimazu T, Ohmori-Matsuda K, Tsuji I. Seasonal variation in home blood pressure measurements and relation to outside temperature in Japan. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2011;33:153–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/10641963.2010.531841.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, National Federation of Health Insurance Societies of Japan. Data health planning guide (revised version). 2017. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-12400000-Hokenkyoku/0000201969.pdf. Accessed Sep 20 2019.

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply indebted to Dr. Shoji Tabata, the staff of Ishikawa-ken Health Service Association, and the staff of Foundation of General Incorporated Foundation Kinki Health Administration Center for their excellent support. We also thank all members of Heiwado Health Insurance Society and Heiwado Occupational Health Care Office, especially Ms. Atsuko Kawamura for her careful coordination of the staff administering the health checkups. We thank Analisa Avila, ELS, of Edanz Group (https://en-author-services.edanzgroup.com/) for editing a draft of this paper.

Funding

This study was partly supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grant number 17K17539) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Three authors (AS, AM, and YK) are salaried employees of the retail company where the present study was conducted. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shima, A., Arima, H., Miura, K. et al. Cluster-randomized controlled trial for the early promotion of clinic visits for untreated hypertension. Hypertens Res 44, 355–362 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-00559-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-00559-0

Keyword

This article is cited by

-

What can be done to reduce undiagnosed or untreated hypertension: effective use of health checkups

Hypertension Research (2025)

-

Healthcare administrators and hypertension at small-to-medium worksites in Okinawa, Japan

Hypertension Research (2025)

-

Enhancing hypertension management: the role of corporate medical health administrators in encouraging hospital visits for workers

Hypertension Research (2025)