Abstract

The prognostic value of electrocardiograms (ECGs) has been reported in predialysis patients but not in incident hemodialysis patients with overhydration and electrolyte disturbances, both of which potentially affect ECG results. We performed a retrospective multicenter cohort study involving incident hemodialysis patients and examined whether ECG parameters immediately before hemodialysis initiation can predict subsequent cardiovascular disease (CVD) using Cox proportional hazards models. We explored potential effect modifications by several electrolytes on the predictive power of ECG abnormalities. Among the 618 enrolled patients, 16%, 10%, 46%, and 22% showed a PR interval ≥ 200 ms, QRS interval ≥120 ms, QTc interval ≥ 450/460 ms (male/female), and left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) by voltage criteria, respectively. Over a median 3-year follow-up, 19% and 16% of the patients developed atherosclerotic and nonatherosclerotic CVD, respectively. The Cox regression model results revealed that the sum of the number of abnormalities in PR, QRS, and QT intervals was a significant risk factor for nonatherosclerotic CVD (hazard ratios (HRs) [95% confidence interval (CI)]: 1.58 [1.24–2.01] per number of abnormalities). The predictive value of LVH for atherosclerotic CVD was attenuated over time. At up to 36 months, although the proportional hazards assumption was met, LVH was significantly associated with atherosclerotic CVD (HR [95% CI]: 1.89 [1.15–3.11]). The adjusted HR was particularly high (HR [95% CI]: 4.02 [1.68–9.60]) among patients who were in the lowest tertile of serum magnesium levels (P for interaction = 0.04). PR, QRS, and QT prolongation additively predicted nonatherosclerotic CVD, while LVH predicted atherosclerotic CVD in the short term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrocardiogram (ECG) measurements are useful for predicting cardiovascular death among predialysis chronic kidney disease patients [1,2,3], as well as patients with heart failure [4, 5] and the general population [6, 7]. In the general population, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) predicts coronary heart disease [6], while prolonged PR interval predicts atrial fibrillation, pacemaker implantation, and all-cause mortality [8]. Among predialysis chronic kidney disease patients, prolonged PR, QRS, and QT intervals and tachycardia were reported to be significant risk factors for cardiovascular mortality. Furthermore, a prolonged QRS interval has been associated with incident myocardial infarction, while a prolonged QT interval has been associated with incident heart failure [1]. Among maintenance hemodialysis patients, a prolonged QT interval has been associated with sudden cardiac death [9] and bradyarrhythmias [10]. Among patients with diabetes mellitus on maintenance dialysis, LVH defined by voltage criteria in ECG has been associated with an increased risk for stroke and sudden death [11]. However, to date, no studies have examined the associations between ECG abnormalities immediately before the initiation of dialysis and future cardiovascular disease (CVD) among incident dialysis patients. The predictive power of ECG for subsequent CVD among incident dialysis patients, if any, might be different from that among predialysis and dialysis patients since incident hemodialysis patients suffer from overhydration and electrolyte abnormalities, which have been found to affect ECG morphologies and intervals [12]. Volume overload decreases QRS amplitude [13], which is a parameter reflective of LVH [14]. Hyperkalemia, which is prevalent among patients with chronic kidney disease stage 5 [15], leads to prolonged PR and QRS intervals and shortened QT intervals [16]. Therefore, QT prolongation might be masked by hyperkalemia. Hypocalcemia, which is prevalent among incident dialysis patients [17], leads to a prolonged QT interval [18]. While a positive association between serum magnesium concentration and QT interval has been reported [19], hypomagnesemia also leads to a prolonged QT interval [20]. These ECG changes by noncardiac factors might limit the predictive power of ECG for subsequent CVD among this patient population. However, how noncardiac factors, such as electrolytes alter the implications of ECG abnormalities for CVD risk prediction is poorly documented. Among patients with hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, or hypermagnesemia, a prolonged QT interval might not be a proxy for cardiac damage, as it is due to transient electrolyte abnormalities and is reversible. Although the effects of serum phosphate concentrations on ECG have not been reported, high serum phosphate levels and low serum magnesium levels, both of which are associated with the incidence of ischemic heart disease [21, 22], might increase the risks of certain ECG abnormalities for atherosclerotic CVD. In this multicenter retrospective cohort study, we enrolled patients starting hemodialysis. The aim of this study was to examine the associations between ECG abnormalities immediately before the initiation of dialysis and the types of subsequent cardiovascular events that occur during the dialysis phase.

Methods

Study design and patient population

In this retrospective multicenter cohort study, we enrolled incident hemodialysis patients with ECG measurements who started hemodialysis between January 2008 and December 2016 at Osaka University Hospital or between June 2008 and July 2018 at the Japan Community Healthcare Organization (JCHO), Osaka Hospital. We excluded patients younger than 20 years old, those who started dialysis at the intensive care unit of the Osaka University Hospital, those with atrial fibrillation or flutter on ECG, and those with pacing on ECG. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of Osaka University Hospital approved the study and waived informed consent based on the retrospective study design (approval number: 18026). We provided patients with the option to opt out of participation.

Data collection and electrocardiogram parameters

We collected the latest data (including ECG parameters) and laboratory data immediately before the initiation of dialysis. We used the data collected within three months prior to dialysis initiation for the analysis. We defined electrolyte abnormalities according to the reference ranges in each hospital. We collected the blood pressure data measured by the nurses during hospitalization.

The PR, QRS, QT intervals, and heart rate were automatically evaluated by ECG devices among all enrolled patients. Because several types of ECG devices were used in our cohort, we selected not the QTc but the raw QT data. Then, the QTc interval was calculated using Bazett’s formula [23]. Prolonged PR, QRS, and QT intervals were defined as PR ≥ 200 ms, QRS ≥ 120 ms, and QTc ≥ 450 ms in male patients and QTc ≥ 460 ms in female patients, respectively [1]. Heart rate was categorized into three groups: < 60 (bradycardia), 60–89 (normocardia), and ≥90 bpm (tachycardia) [1]; LVH was defined using the Sokolow-Lyon criteria (SV1 + RV5/V6 ≥ 3.5 mV) [24].

Outcomes

We followed up patients who started dialysis at Osaka University Hospital and JCHO Osaka Hospital between August 2017 and September 2018, respectively. All patients were hospitalized upon the initiation of hemodialysis in our cohort. The primary outcome was death and rehospitalization for atherosclerotic or nonatherosclerotic CVD. Outcome information was collected through medical records or common questionnaires sent to each dialysis facility. Atherosclerotic CVD included myocardial infarction, unstable angina, nonhemorrhagic stroke, peripheral vascular disease (including amputation), and aortic dissection or rupture [25]. Nonatherosclerotic CVD included heart failure, arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation and tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation, sick sinus syndrome, atrioventricular block, and cardiac ablation), hemorrhagic stroke, sudden death, fatal pulmonary embolism, and death due to unspecified CVD [25]. Patients were censored at the date of kidney transplantation or when they were lost to follow-up.

Statistical analyses

The baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients are summarized. Categorical variables are presented as percentages. Continuous variables with a normal distribution are presented as the mean (SD). We described the cardiovascular event rates of patients stratified by each ECG abnormality.

We examined the association between ECG abnormalities and first CVD events using the log-rank test, Kaplan–Meier curves, and Cox proportional hazards model stratified by hospital. The generalized Wilcoxon test was used instead of the log-rank test, if needed. We examined the proportional hazards assumption using the Schoenfeld residuals and employed stepwise backward methods (exclusion criteria: p ≥ 0.1) for multivariate Cox models. All ECG abnormalities (prolonged PR, QRS, QT, LVH, bradycardia, and tachycardia), age, sex, body mass index, systolic blood pressure (SBP), eGFR, diabetes, past medical history (coronary artery disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, cardiac ablation, pacemaker, peripheral artery disease, cerebral infarction, and cerebral hemorrhage), smoking status, prescriptions (dihydropyridine and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, beta blockers, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, diuretics, and insulin), and electrolyte abnormalities (both hyper- and hypo-, kalemia, calcemia, phosphatemia, and magnesemia) were initially entered into the model. Age, sex, and history of CVD were forcedly entered into the models, regardless of the P values. In analyses of the risk for nonatherosclerotic CVD, the sum of the number of abnormalities in PR, QRS, and QT intervals was included in the models instead of each ECG abnormality because of multicollinearity. To explore the effect modifications by electrolyte levels, in addition to the covariates selected for the main analysis, we entered interaction terms between the tertiles of serum magnesium (or phosphate) levels and ECG abnormalities that predict atherosclerotic CVD into the multivariable Cox models. Similarly, we examined the significance of interaction terms between the prolonged QT interval and tertiles of serum calcium, potassium, and magnesium levels in the same models for atherosclerotic CVD.

P values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata/IC 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Prevalence of ECG abnormalities

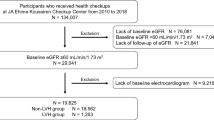

Among the 618 enrolled patients (Fig. 1), the mean age was 65 years, 70% were male, and the mean eGFR was 5.1 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Table 1). Overall, 50% of the patients had their ECG evaluated within 2 days before dialysis initiation, and 75% of the patients had their ECG evaluated within 2 weeks before dialysis initiation (Supplementary Fig. 1). The most common ECG abnormality was a prolonged QT interval, followed by LVH, a prolonged PR interval, tachycardia, a prolonged QRS interval, and bradycardia (Fig. 2). Among patients with a prolonged QRS interval, 75% were automatically diagnosed with bundle branch block by electrocardiographic equipment. Complete right bundle branch block accounted for 94% of the diagnosed bundle branch block cases. Serum potassium, calcium, and phosphate levels were measured in 95% of the patients within 1 day before dialysis initiation, and serum magnesium levels were measured in 75% of the patients one day before dialysis initiation. In the other patients, electrolytes were measured within three months before dialysis was initiated.

Flow diagram. Patients with atrial fibrillation or on pacemakers at ECG measurements were excluded from the baseline analysis. For the analysis of predictors of CVD after discharge, we excluded patients who were pronounced deceased or developed CVD before discharge. AF atrial fibrillation, AFL atrial flutter, ECG electrocardiogram, ICU intensive care unit, CVD cardiovascular disease, HD hemodialysis

Patients with higher phosphate levels had significantly higher heart rates (p < 0.001). This association was significant even after adjusting for age, male sex, and history of CVD. Patients with LVH had higher SBP than patients without LVH (mean SBP: 151 mmHg vs. 146 mmHg, respectively; Student’s t-test: p = 0.04). Prior history of coronary artery disease tended to be more frequent in patients with LVH than in patients without LVH (15% vs. 9%, respectively; Fisher’s exact test: p = 0.07). Patients with hypocalcemia had an increased likelihood of having prolonged QTc interval (odds ratio [95% confidence interval (CI)]: 2.66 [1.89–3.74]). The odds ratios [95% CI] of coronary artery disease and heart failure for prolonged QRS intervals were 2.66 [1.30–5.43] and 2.13 [1.08–4.20], respectively.

Nonatherosclerotic CVD

During a median follow-up period of 39 months (IQR, 19–70), 96 patients (16%) developed nonatherosclerotic CVD. Fatal CVD accounted for 21% of nonatherosclerotic CVD events. The most common nonatherosclerotic CVD event was heart failure (34%), followed by arrhythmia (30%) and hemorrhagic stroke (15%) (Supplementary Fig. 2). The most frequent arrhythmic event was atrial fibrillation (50% of arrhythmic events) (Supplementary Fig. 3). Patients with a prolonged PR interval had higher rates of nonatherosclerotic CVD than those who did not (9.5% vs. 3.5%, respectively; p < 0.001 by chi-square test), while patients with a prolonged QRS interval had higher rates of nonatherosclerotic CVD than those who did not (13.3% vs. 3.5%, respectively; p < 0.001 by chi-square test). Patients with a prolonged QT interval also had higher rates of CVD than those who did not (20.5% vs. 11.4%, respectively; p = 0.002 by chi-square test) (Fig. 2). Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that patients with a greater number of these ECG abnormalities demonstrated a significantly higher likelihood of developing nonatherosclerotic CVD (Fig. 3A). The sum of the number of abnormalities in PR, QRS, and QT intervals was significantly associated with an increased risk for subsequent nonatherosclerotic CVD in both the univariate and multivariate Cox proportional analyses (hazard ratio [95% CI]: 1.58 [1.24–2.01] per number of ECG abnormalities, P for trend <0.001), independent of hyperphosphatemia and hypercalcemia, both of which were significant risk factors for nonatherosclerotic CVD (hazard ratio [95% CI]: 1.93 [1.13–3.31], 6.76 [2.71–16.9], respectively) (Table 2).

Kaplan–Meier failure curve function for time-to-nonatherosclerotic CVD stratified by the sum of the numbers of abnormalities in PR, QRS, QT intervals (A) and function for time-to-atherosclerotic CVD stratified by LVH (B). Patients with a greater number of ECG abnormalities, including PR, QRS, and QT prolongation, had a significantly higher rate of nonatherosclerotic CVD. Kaplan–Meier curves of patients with and without LVH across each other at 80 months (Cox proportional hazards assumption was not met). Therefore, we used the generalized Wilcoxon test instead of the log-rank test. In the early phase, patients with LVH had a significantly higher rate of atherosclerotic CVD. The curves were truncated when the percentage of patients remaining at risk was approximately 10%. CVD cardiovascular disease, LVH left ventricular hypertrophy, N the sum of the numbers of abnormalities in PR, QRS, and QT intervals

Atherosclerotic CVD

During a median follow-up period of 39 months (IQR, 19–70), 120 patients (19%) developed atherosclerotic CVD. Fatal CVD accounted for 3% of atherosclerotic CVD events. The most common CVD was coronary artery disease (53%), followed by nonhemorrhagic stroke (22%), and peripheral artery disease (21%) (Supplementary Fig. 2). The Kaplan–Meier analysis of patients with and without LVH demonstrated a significant difference in the time to outcome (Fig. 3B). Risk stratification by LVH for atherosclerotic CVD was attenuated over time (Fig. 3B). In a univariate Cox regression analysis for atherosclerotic CVD risk factors, the proportional hazards assumption was not met for LVH. Therefore, we restricted the analyses within 36 months, for which the proportional hazards assumption was met. Within the time frame, a prolonged QRS interval and LVH were significantly associated with the development of atherosclerotic CVD. In the multivariate model, only LVH was significantly associated with an increased risk for atherosclerotic CVD (hazard ratio [95% CI]: 1.89 [1.15–3.11]) (Table 2).

Effect modifications by electrolyte levels

Hypocalcemia, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypomagnesemia were observed in 34%, 22%, 74%, and 10% of patients, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4). Serum magnesium levels were found to modify the association between LVH and atherosclerotic CVD (P for interaction =0.04). LVH was a significant risk factor for atherosclerotic CVD only among patients in the lowest tertile of serum magnesium levels (hazard ratio: 4.02, 95% CI: 1.68–9.60) (Fig. 4). The other interactions we examined based on the aforementioned hypotheses (Introduction) did not show statistical significance (Fig. 4).

Effect modifications by electrolyte levels on the predictive power of LVH (A) and QT prolongation (B) for atherosclerotic CVD. Serum magnesium levels significantly modified the risk for atherosclerotic CVD associated with LVH. cCa corrected calcium levels, CVD cardiovascular disease, ECG electrocardiogram, K serum potassium levels, LVH left ventricular hypertrophy, Mg serum magnesium levels, iP serum phosphate levels, T1–3 tertiles 1–3

Discussion

In this retrospective multicenter cohort study, we revealed that the sum of the number of abnormalities in PR, QRS, and QT interval prolongation was a significant risk factor for nonatherosclerotic CVD. In addition, we found LVH by voltage criteria was a significant risk factor for atherosclerotic CVD early after the initiation of hemodialysis. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the associations between ECG parameters and types of future CVD events among incident dialysis patients. ECG is a noninvasive and low-cost cardiac examination. Predicting the type of CVD and related risk could facilitate more individualized care, which could prevent hospitalization due to CVD and the associated high medical expenses [26].

PR, QRS, and QT interval prolongation synergistically increased the risk for subsequent nonatherosclerotic CVD events among incident dialysis patients, including atrial fibrillation, pacemaker implantation, and heart failure. This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies. In the general population, a prolonged PR interval was reported to be a risk factor for developing atrial fibrillation, requiring pacemaker insertion, and overall mortality [8]. Among hemodialysis patients who use implantable loop recorders, the PR interval was found to be associated with the development of bradyarrhythmias [10]. A prolonged PR interval may result from conduction retardation in the atrial myocardium, the AV node, and the bundle of His [27]. PR interval prolongation at the initiation of hemodialysis might reflect atrial remodeling and diastolic dysfunction that developed during predialysis chronic kidney disease. Atrial fibrillation is related to atrial remodeling, which also affects atrioventricular conduction [28]. In addition, a prolonged PR interval may result in elevated left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, diastolic mitral regurgitation, and reduced left ventricular pump function [29]. In fact, a prolonged PR interval is a proxy of diastolic dysfunction [30], which leads to heart failure [31]. A prolonged QRS interval is related to left ventricular systolic dysfunction [32] and is a risk factor for subsequent heart failure among patients with heart failure [33] or hypertension [34]. Prolonged QRS interval is a risk for atrial fibrillation among patients with left ventricular dysfunction [35]. A prolonged QT interval has also been reported to be associated with cardiovascular mortality among predialysis chronic kidney disease patients [1] and to predict sudden death among hemodialysis patients [9].

We revealed that hyperphosphatemia and hypercalcemia were significant risk factors for nonatherosclerotic CVD. Since elevated serum phosphate and calcium levels stimulate the production of fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) [36], these associations might be explained by elevated FGF-23. FGF-23 increases spontaneous beating rates of pulmonary vein cardiomyocytes, which can be a trigger of arrhythmogenesis [37]. In fact, a higher circulating FGF-23 concentration is associated with incident atrial fibrillation [38]. Moreover, we found a positive association between serum phosphate levels and heart rate.

LVH by voltage criteria at the initiation of hemodialysis predicted short-term atherosclerotic CVD, and LVH at the initiation of hemodialysis might reflect the severity of the underlying atherosclerosis that developed during the predialysis period. In fact, patients with LVH had higher SBP than patients without LVH in our cohort. Changes in blood pressure control due to the initiation of hemodialysis might be one reason why LVH did not predict long-term atherosclerotic CVD. Previous studies among prevalent dialysis patients also support our results. In these studies, LVH was a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality [39, 40]. Conversely, our results were not consistent with some previous studies, such as the CRIC study, in which LVH on ECG did not predict the incidence of myocardial infarction among predialysis chronic kidney disease patients [1]. The discrepancy between our results and those of the previous study might stem from the difference in volume status. We measured ECG immediately before the initiation of hemodialysis, when patients suffer from volume overload, which is not the case with early stages of chronic kidney disease. Since volume overload reduces ECG voltage [12], only severe myocardial hypertrophy can be detected by voltage criteria at this point in time. In fact, the prevalence of LVH by ECG measured early after the initiation of hemodialysis (18.9%) was reported to be much lower than the prevalence of LVH by echocardiogram (68.8%) [41], which supported the probable underdiagnosis of LVH in our study.

Electrocardiographic LVH was a significant risk factor for atherosclerotic CVD only among patients in the lowest tertile of magnesium. This finding might be due to the protective effects of magnesium against atherosclerosis. In our previous randomized trial, supplementation with magnesium suppressed the progression of coronary artery calcification [42]. Furthermore, hypomagnesemia potentially promotes vasoconstriction, and coronary thrombosis. Hypomangesemia impaired the release of a nitric oxide, vasodilator [43]. In addition, magnesium inhibits platelet-dependent thrombosis [44]. Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find a significant interaction between LVH by ECG and serum phosphate levels on the risk for atherosclerotic CVD. This might be because the hyperphosphatemia observed before the initiation of dialysis did not persist after it.

Our study has several strengths that should be noted. First, our ECG data were obtained before the initiation of hemodialysis, which means that these ECG data were not affected by changes in volume status or electrolytes due to hemodialysis. In previous studies evaluating the prognostic implications of ECG among incident dialysis patients, ECG was recorded early after the initiation of hemodialysis [41, 45]. Second, our study is the first to examine the effect of modification by several electrolytes on the predictive power of ECG abnormalities. We found that LVH by ECG was a strong risk factor for atherosclerotic CVD, especially among patients with low magnesium levels.

Our study has several limitations that should also be noted. First, the outcomes included hospitalization for CVD, but indications for hospitalization can vary among physicians. Second, patients with atrial fibrillation and pacing at ECG measurement were excluded from our cohort. Thus, the prognostic implications of ECG abnormalities among these patients remain unknown. Third, there is a possibility of misclassification. For example, nonatherosclerotic cardiovascular events in our study might have included heart failure due to the onset of coronary heart disease (atherosclerotic CVD).

In conclusion, prolonged PR, QRS, and QT intervals additively predicted nonatherosclerotic CVD events after the initiation of hemodialysis, while LVH defined by voltage criteria at the initiation of hemodialysis predicted atherosclerotic CVD in the short term. ECG measurements at the initiation of hemodialysis can be useful for predicting the types of cardiovascular events that may occur after the initiation of hemodialysis.

References

Deo R, Shou H, Soliman EZ, Yang W, Arkin JM, Zhang X, et al. Electrocardiographic measures and prediction of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular death in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:559–69.

Kestenbaum B, Rudser KD, Shlipak MG, Fried LF, Newman AB, Katz R, et al. Kidney function, electrocardiographic findings, and cardiovascular events among older adults. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:501–8.

Dobre M, Brateanu A, Rashidi A, Rahman M. Electrocardiogram abnormalities and cardiovascular mortality in elderly patients with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:949–56.

Gouda P, Brown P, Rowe BH, McAlister FA, Ezekowitz JA. Insights into the importance of the electrocardiogram in patients with acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:1032–40.

Park SJ, On YK, Byeon K, Kim JS, Choi JO, Choi DJ, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes depending on electrical dyssynchrony markers in patients presenting with acute heart failure: clinical implication of the first-degree atrioventricular block and QRS prolongation from the Korean Heart Failure registry. Am Heart J. 2013;165:57–64.

Kannel WB, Abbott RD. A prognostic comparison of asymptomatic left ventricular hypertrophy and unrecognized myocardial infarction: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1986;111:391–7.

Rautaharju PM, Kooperberg C, Larson JC, LaCroix A. Electrocardiographic abnormalities that predict coronary heart disease events and mortality in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative. Circulation. 2006;31:473–80.

Cheng S, Keyes MJ, Larson MG, McCabe EL, Newton-Cheh C, Levy D, et al. Long-term outcomes in individuals with prolonged PR interval or first-degree atrioventricular block. JAMA. 2009;301:2571–7.

Genovesi S, Rossi E, Nava M, Riva H, De Franceschi S, Fabbrini P, et al. A case series of chronic haemodialysis patients: mortality, sudden death, and QT interval. Europace. 2013;15:1025–33.

Silva RT, Martinelli Filho M, Peixoto Gde L, Lima JJ, Siqueira SF, Costa R, et al. Predictors of Arrhythmic events detected by implantable loop recorders in renal transplant candidates. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2015;105:493–502.

Krane V, Heinrich F, Meesmann M, Olschewski M, Lilienthal J, Angermann C, et al. German diabetes and dialysis study investigators: electrocardiography and outcome in patients with diabetes mellitus on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:394–400.

Poulikakos D, Malik M. Challenges of ECG monitoring and ECG interpretation in dialysis units. J Electrocardiol. 2016;49:855–9.

Madias JE, Narayan V. Augmentation of the amplitude of electrocardiographic QRS complexes immediately after hemodialysis: a study of 26 hemodialysis sessions of a single patient, aided by measurements of resistance, reactance, and impedance. J Electrocardiol. 2003;36:263–71.

Hancock EW, Deal BJ, Mirvis DM, Okin P, Kligfield P, Gettes LS, et al. American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; American College of Cardiology Foundation; Heart Rhythm Society: AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part V: electrocardiogram changes associated with cardiac chamber hypertrophy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:992–1002.

Oka T, Hamano T, Sakaguchi Y, Yamaguchi S, Kubota K, Senda M, et al. Proteinuria-associated renal magnesium wasting leads to hypomagnesemia: a common electrolyte abnormality in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2019;34:1154–62.

Surawicz B. Relationship between electrocardiogram and electrolytes. Am Heart J. 1967;73:814–34.

Yamaguchi S, Hamano T, Doi Y, Oka T, Kajimoto S, Kubota K, et al. Hidden hypocalcemia as a risk factor for cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality among patients undergoing incident hemodialysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4418.

Heemskerk CPM, Pereboom M, van Stralen K, Berger FA, van den Bemt PMLA, Kuijper AFM, et al. Risk factors for QTc interval prolongation. Eur J Clin Pharm. 2018;74:183–91.

Noordam R, Young JW, Salman R, Kanters KJ, van den Berg ME, van Heemst D, et al. Effects of Calcium. Magnes, Potassium Concentrations Ventricular Repolarization Unselected Individ J Am Coll Caridol. 2019;73:3118–31.

Shimaoka T, Wang Y, Morishima M, Miyamoto S, Ono K. Magnesium deficiency causes transcriptional downregulation of Kir2.1 and Kv4.2 channels in cardiomyocytes resulting in QT interval prolongation. Circ J. 2020;84:1244–53.

Tagawa M, Hamano T, Nishi H, Tsuchida K, Hanafusa N, Fukatsu A, et al. Mineral metabolism markers are associated with myocardial infarction and hemorrhagic stroke but not ischemic stroke in hemodialysis patients: a longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e11468.

Liao F, Folsom AR, Brancati FL. Is low magnesium concentration a risk factor for coronary heart disease? The atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) Study. Am Heart J. 1998;136:480–90.

Bazett HC. An analysis of time relations of electrocardiogram. Heart. 1920;7:353–70.

Sokolow M, Lyon TP. The ventricular complex in left ventricular hypertrophy as obtained by unipolar precordial and limb leads. Am Heart J. 1949;37:161–86.

Wheeler DC, London GM, Parfrey PS, Block GA, Correa-Rotter R, Dehmel B, et al. Effects of cinacalcet on atherosclerotic and nonatherosclerotic cardiovascular events in patients receiving hemodialysis: the evaluation of cinacalcet HCL therapy to lower cardiovascular events (EVOLVE) Trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001363.

United States Renal Data System. 2018 USRDS annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD, 2018.

Schumacher K, Dagres N, Hindricks G, Husser D, Bollmann A, Kornej J. Characteristics of PR interval as predictor for atrial fibrillation: association with biomarkers and outcomes. Clin Res Cardiol. 2017;106:767–75.

Iwasaki YK, Nishida K, Kato T, Nattel S. Atrial fibrillation pathophysiology: implications for management. Circulation. 2011;124:2264–74.

Salden FCWM, Kutyifa V, Stockburger M, Prinzen FW, Vernooy K. Atrioventricular dromotropathy: evidence for a distinctive entity in heart failure with prolonged PR interval? Europace. 2018;20:1067–77.

Namdar M, Biaggi P, Stähli B, Bütler B, Casado-Arroyo R, Ricciardi D, et al. A novel electrocardiographic index for the diagnosis of diastolic dysfunction. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79152.

Kane GC, Karon BL, Mahoney DW, Redfield MM, Roger VL, Burnett JC Jr, et al. Progression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and risk of heart failure. JAMA. 2011;306:856–63.

Sandhu R, Bahler RC. Prevalence of QRS prolongation in a community hospital cohort of patients with heart failure and its relation to left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:244–6.

Shamim W, Yousufuddin M, Cicoria M, Gibson DG, Coats AJ, Henein MY. Incremental changes in QRS duration in serial ECGs over time identify high risk elderly patients with heart failure. Heart. 2002;88:47–51.

Okin PM, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, Edelman JM, Dahlöf B. Incidence of heart failure in relation to QRS duration during antihypertensive therapy: the LIFE study. J Hypertens. 2009;27:2221–7.

El-Chami MF, Brancato C, Langberg J, Delurgio DB, Bush H, Brosius L, et al. QRS duration is associated with atrial fibrillation in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:132–83.

Quinn SJ, Thomsen ARB, Pang JL, Kantham L, Bräuner-Osborne H, Pollak M, et al. Interactions between calcium and phosphorus in the regulation of the production of fibroblast growth factor 23 in vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E310–320.

Huang SY, Chen YC, Kao YH, Hsieh MH, Lin YK, Chung CC, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 dysregulates late sodium current and calcium homeostasis with enhanced arrhythmogenesis in pulmonary vein cardiomyocytes. Oncotarget. 2016;7:69231–42.

Mathew JS, Sachs MC, Katz R, Patton KK, Heckbert SR, Hoofnagle AN, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and incident atrial fibrillation: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS). Circulation. 2014;130:298–307.

Covic AC, Buimistriuc LD, Green D, Stefan A, Badarau S, Kalra PA. The prognostic value of electrocardiographic estimation of left ventricular hypertrophy in dialysis patients. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2013;18:188–98.

Cice G, Di Benedetto A, D’Andrea A, D’Isa S, De Gregorio P, Marcelli D, et al. Heart rate as independent prognostic factor for mortality in normotensive hemodialysed patients. J Nephrol. 2008;21:704–12.

Kim SJ, Oh HJ, Yoo DE, Shin DH, Lee MJ, Kim HR, et al. Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and outcome in hemodialysis patients. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35534.

Sakaguchi Y, Hamano T, Obi Y, Monden C, Oka T, Yamaguchi S, Matsui I, et al. A randomized trial of magnesium oxide and oral carbon adsorbent for coronary artery calcification in predialysis CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30:1073–85.

Pearson PJ, Evora PR, Seccombe JF, Schaff HV. Hypomagnesemia inhibits nitric oxide release from coronary endothelium: protective role of magnesium infusion after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:967–72.

Shechter M, Merz CN, Paul-Labrador M, Meisel SR, Rude RK, Molloy MD, et al. Oral magnesium supplementation inhibits platelet-dependent thrombosis in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:152–6.

Tereshchenko LG, Kim ED, Oehler A, Meoni LA, Ghafoori E, Rami T, et al. Electrophysiologic substrate and risk of mortality in incident hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3413–20.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Shihomi Maeda, Dr. Fumiyuki Morioka, Dr. Syou Matsui, Dr. Sayaka Katou, Dr. Akane Ito, Dr. Eriko Iwahashi, (JCHO Osaka Hospital), Dr. Kiyoshi Shozu (Aino Hospital), Dr. Yutaro Azuma (Azuma Dialysis Clinic), Dr. Akira Wada (Azuma Renal Clinic), Dr. Jong Il Kim (Chibune Kidney and Dialysis Clinic), Dr. Sachiko Yamada (Saiseikai Ibaraki Hospital), Dr. Yasuhiro Enomoto (Enomoto Clinic), Dr. Ryoichi Miyazaki (Fujita Memorial Hospital), Dr. Yuji Murata (Harbor-Town Clinic), Dr. Toshiaki Hirabayashi (Heimeikai Clinic), Dr. Fukuhara Isao (Heisei Urologic Clinic), Dr. Shigeru Yamaguchi (Hokusetsu General Hospital), Dr. Takashi Tomokuni (Ibaraki Iseikai Hospital), Dr. Toyohumi Fukuda (Ibuki Clinic), Dr. Kazuyuki Hayashi (Ikeda Municipal Hospital), Dr. Nobuyuki Imai (Imai Naika Clinic), Dr. Yasuji Kuroda (Inadera Dialysis Clinic), Dr. Yuko Fujiwara, Dr. Yoshihiro Tsujimoto (Inoue Hospital), Dr. Takahisa Hotta (Iseikai Fuzoku Clinic), Dr. Takahiro Fujii (Itami Bara Clinic), Dr. Tomoko Yokokawa (Itami Gardens Clinic), Dr. Kazuo Yasuda (Jinyuukai Yasuda Clinic), Dr. Masanori Joko (Joko Clinic), Dr. Yukiomi Namba (Jouto Iseikai Clinic), Dr. Jyunya Takahara (Takahara Clinic), Dr. Mayumi Sakurai (Jyurakukai Clinic), Dr. Masato Baden (Kaiseikai Takarazuka Hospital), Dr. Hisato Nakamori (Katano Hospital), Dr. Hironori Kawamura (Kawamura Clinic), Dr. Chikako Monden (Kisei Hospital), Dr. Ken Kishida (Kishida Clinic), Dr. Eikun Maruyama (Kitagawa Clinic), Dr. Fumi Sato (KKR Otemae Hospital), Dr. Shigeru Hanada (Koseikai Taisei Clinic), Dr. Akihisa Kuki (Kuki Clinic), Dr. Takayuki Okamoto (Kyoritsu Hospital), Dr. Mitsuru Kubo (Kyowakai Hospital), Dr. Haruki Fuse (Maizuru Kyosai Hospital), Dr. Yutaka Matsui (Matsui Dietary & Dementia Clinic), Dr. Noriko Mikami (Mikami Clinic), Dr. Hiroshi Miyao (Miyo Urology Clinic), Dr. Mutsuko Mori (Mori Clinic), Dr. Rumi Sakai (Motoyama Sakai Rumi Clinic), Dr. Shunro Agata (Nagahara Hospital), Dr. Takanori Nagai (Nagai Clinic), Dr. Hideyuki Nakagawa (Nakagawa Clinic), Dr. Masashi Shinozaki (Nakano Clinic), Dr. Yasuo Ohyama (Neyagawa Keijinkai Clinic), Dr. Kanji Nozaki (Nozaki Clinic), Dr. Tetsuya Kaneko (NTT West Osaka Hospital), Dr. Takeshi Omichi (Ohmichi Clinic), Dr. Motohiro Okamura (Okamuraiin Jin Clinic), Dr. Akira Okasho (Okasho Urology Clinic), Dr. Kiyoshi Goto (Ono-Naika Clinic), Dr. Hidekazu Shimizu (Onoyama Clinic), Dr. Masahiro Kyo (Osaka Umeda Iseikai Dialysis Clinic), Dr. Nobuhiko Narukawa (Sakuragaoka Hospital), Dr. Kei Hirai (Sanko Clinic), Dr. Kazuhisa Yamamoto (Sanko Hospital), Dr. Satoshi Sasaki (Sasaki Medical Clinic), Dr. Masugi Satoh (Satoh Clinic Kuzuha), Dr. Daisuke Nakagawa (Second Rokushima Clinic), Dr. Hiroyuki Araki (Settsu Iseikai Hospital), Dr. Shintaro Yamanaka (Shingu Municipal Medical Center), Dr. Atsushi Yokota (Shin-Osaka Iseikai Clinic), Dr. Ken Takahara (Sone Hospital), Dr. Zenzo Fujii (St. Hill Hospital), Dr. Jun Matsuda (Suita City Hospital), Dr. Yoshinori Sai (Suminodo Clinic), Dr. Kanji Yoshida (Suzawa Clinic), Dr. Tadashi Hatayama (Neyagawaikunobyouinn), Dr. Yukito Kokado, Dr. Tohru Takahashi (Takahashi Clinic), Dr. Kazuyuki Takahashi (Takahashi Kazuyuki Clinic), Dr. Yoshiaki Hirosue (Takasago Municipal Hospital), Dr. K.Y. (Tanaka Clinic), Dr. Masatou Tanaka (Tanaka Urology Clinic Dialysis Center Furuedai), Dr. Hiroko Tokizane (Tokizane Clinic), Dr. Keiji Isshiki (Tomita Clinic), Dr. Jun Tomita (Toyonaka Watanabe Clinic, Kansai Medical Hospital), Dr. Yumiko Honda (Toyonakamidorigaoka Hospital), Dr. Takahide Sugiyama (Tsukuno Fujii Clinic), Dr. Akira Moriguchi (Umeda-Higashi Blood Purification Clinic), Dr. Takatoshi Yamamoto (Yamamoto Clinic), Dr. Masaru Shin (Yao Tokushukai General Hospital), and Dr. Toru Yoshie (Yoshie Hospital) for their assistance in collecting data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yamaguchi, S., Hamano, T., Oka, T. et al. Electrocardiogram findings at the initiation of hemodialysis and types of subsequent cardiovascular events. Hypertens Res 44, 571–580 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-00592-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-00592-z