Abstract

A shift towards high folate concentration has emerged following folate fortification. However, the association between folate and health outcomes beyond neural tube defects remains inconclusive. To assess the relationship between red blood cell (RBC) folate and the risk of cardiovascular death among hypertensive patients, we analyzed the data of 2,986 adults aged 19 or older with hypertension who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1991–1994) as the baseline examination and were followed up through December 31, 2010. After 32,743 person-years of follow-up with an average of 11.7 (standard error = 0.03) years, 1192 deaths were recorded with 579 cardiovascular deaths. The median survival time was significantly shorter in adults in the high folate quartile than in patients in the low folate quartile: 11.97 vs. 13.85 years for heart diseases and 13.37 vs. 14.82 years for myocardial infarction deaths. The cardiovascular mortality was 13.04, 16.95, and 26.61/1,000 person-years for the groups with low, intermediate and high folate quartiles, respectively. After adjustment for age, sex and other factors, a J-shaped association emerged. The hazard ratios (HRs) of all cardiovascular deaths in patients with low, intermediate, and high folate quartiles were 1.09 (0.94, 1.27), 1.00 (reference), and 1.44 (1.31, 1.58), respectively. The corresponding HRs of acute myocardial infarction were 1.13 (0.86, 1.50), 1.00, and 2.13 (1.77, 2.57), respectively. The estimates remained significant after adjustment for BMI and medication use. Compared to moderate RBC folate levels, high folate levels were significantly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular deaths, especially acute myocardial infarction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The association between folate and health outcomes other than neural tube defects has been a topic of debate for years. The results from observational studies are inconsistent. Some studies [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8], mostly conducted in prefortification populations or countries where folate fortification is not mandatory, found a significantly increased cardiovascular risk among participants with low folate. However, no association between cardiovascular risk and folate levels, whether measured by dietary intake, food supplementation [9], or blood folate levels [9,10,11], has been reported. Most recently, with postfortification populations included, studies reported that supplemental folic acid was associated with increased mortality [12]. Both low and high serum folate levels, compared to a moderate level, were associated with increased all-cause mortality [13], and high red blood cell (RBC) folate was associated with various indicators of metabolic disorders [14].

The results from randomized trials testing the effectiveness of folate supplementation for secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) were even more inconsistent. Folic acid has been observed to be beneficial for decreasing cholesterol concentrations, enhancing endothelial functions [15], reducing plasma homocysteine (Hcy) levels [16,17,18,19], improving serum total antioxidant capacity, and ultimately boosting glycemic control and insulin sensitivity [19]. Folic acid, together with other B vitamins, reduced the need for revascularization in patients with balloon angioplasty [20], increased the efficacy of classic antihypertensives [21, 22], and lowered both the risk of incident stroke [23] and Framingham risk score of CVD [24]. However, it is of concern that almost all the studies reporting beneficial effects of folic acid on cardiovascular endpoints were conducted in countries where folate fortification has not yet been fully implemented, such as China [21,22,23,24], Iran [18, 19], Poland [16], and Switzerland [20], and the baseline folate concentration remained relatively low in these countries. Almost all large trials on secondary prevention of CVD conducted among US adults and published in highly ranked journals failed to find evidence to support a cardiovascular benefit [25,26,27,28,29]. Instead, a trend of increasing cardiac events was observed in patients treated with folic acid [26, 28], and an increased need for revascularization intervention [30]; and elevated all-cause mortality were also noted [31].

A vital shift towards higher folate concentrations has emerged in the United States following the full implementation of mandatory folate fortification [32], potentially changing the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of many nutrients and agents. Efforts should be intensified to assess the relationship between folate and health outcomes other than neural tube defects. We analyzed the data of hypertensive adults from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), a nationally representative cohort, to describe the relationship between cardiovascular mortality and RBC folate, a biomarker for a relative long-term folate status.

Methods

Study population

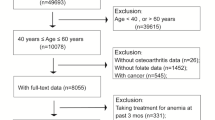

The NHANES was conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, among a nationwide probability sample of noninstitutionalized civilians. Since serum Hcy, the major confounder of the association of interest, was measured in phase II only (1991–1994) of NHANES III, we restricted the analyses to 8758 adults aged 19 years or older who participated in phase II and were asked about the diagnosis with hypertension at the baseline survey or before. After the exclusion of 5772 survey participants for various reasons (Fig. 1), a total of 2986 adults with hypertension were retained for analysis. The NHANES protocol was reviewed and approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Institutional Review Board (IRB), and the current analysis was exempted from ethics review by the Georgia Southern University IRB committee due to the nature of secondary data analyses.

Flow chart of the study population, 2986 US adults aged 19 and older with hypertension, NHANES 1991–2010. NDI National Death Index, NHANES the National Health Examination and Nutrition Survey. 1Blood pressure (BP) was measured three times in the mobile examination center (in home if not able to make a trip to a mobile examination center), with the participant seated, and using an appropriate cuff size. All available measurements from an individual were averaged to obtain the BP value used in the analyses. Hypertension was defined as present if a participant reported both ever being told that she or he had high BP and current use of antihypertensive medications, or if the average measured BP was ≥140mmHg systolic or ≥90mmHg diastolic, the clinical definition of hypertension used when NHANES III was conducted

Baseline data collection

Baseline data were collected as a part of the NHANES III during an in-home interview and a subsequent visit to a mobile examination center (MEC) using standardized questionnaires under controlled and constant environmental conditions. Trained technicians drew blood and processed it in MECs for transportation to appropriate laboratories. All laboratory measurements were carried out in a blinded fashion with respect to vital status and other clinical data.

Assessment of RBC folate concentrations

RBC folate concentrations were measured using whole blood samples and assayed with a Quantaphase II folate radioassay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, California, US). Sex-specific cutoffs were derived from the patients included to categorize the study participants into three groups: (i) RBC folate concentrations ≥256.47 ng/mL (581.17 nmol/L) for men and 290.42 ng/mL (658.08 nmol/L) for women as the upper quartile (high-folate group hereafter), (ii) <136.99 ng/mL (310.38 nmol/L) for men and <134.36 ng/mL (304.43 nmol/L) for women as the lower quartile (low-folate group hereafter), and (iii) the remaining values as interquartile (group with moderate folate).

Socioeconomic status and other covariates

Ethnicity was coded as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, and others. Family income level was assessed using the poverty income ratio (PIR), which was calculated using the previous year’s family income and family size. The respondents who self-reported alcohol drinking were categorized as ‘heavy’ (if the respondents reported more than 10 days in the past 12 months on which five drinks or more were consumed) and ‘moderate’ (if 10 days or less were reported on which five drinks or more were consumed in the past 12 months) [33, 34]. Self-reported smokers were grouped as current smokers and former smokers. The current smokers were further defined as ‘heavy’ (if the respondents reported that in the past five days 40 cigarettes or more were smoked) and ‘moderate’ (if fewer than 40 but more than 0 cigarettes were smoked). Body weight and height were measured directly and used to calculate body mass index (BMI) to classify study participants as obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), overweight (29.9–25 kg/m2), healthy weight (24.9–18.5 kg/m2), and underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2). Self-rated health conditions have been associated with total mortality and may serve as a proxy for risk-adjustment efforts [35]. In the baseline interview, the participants were asked: “Have you ever been told by a doctor that you had one or more of the following general medical illnesses: asthma, arthritis, cancer, chronic bronchitis, diabetes, hypertension, gout, lupus, stroke, heart disease, or thyroid disease?” The history of CVD was assessed from the answers to this question. Serum cotinine, an alkaloid found in tobacco and the predominant metabolite of nicotine, was used to control for underreporting of cigarette smoking or exposure to environmental tobacco smoke.

As the main regulatory enzyme, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) plays a crucial role in folate metabolism. A polymorphism of the MTHFR gene, C677T, leads to a reduction in enzyme activity, resulting in decreased folate levels and increased plasma Hcy [36]. Approximately 20–40% of white and Hispanic Americans are heterozygous for MTHFR C677T [37]. It is desirable that the relationship between folate and cardiovascular endpoints should be evaluated, considering the MTHFR gene C677T polymorphism [38, 39]. In the absence of genetic data, we used serum Hcy concentration as the surrogate of the MTHFR C677T TT genotype since the MTHFRTT genotype was strongly associated with blood Hcy concentrations [37]. Hcy was measured with the high-performance liquid chromatography method. Data on prescription drugs, including medications for endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases and immunity disorders, were obtained by trained interviewers who inventoried all prescription drugs used within a 1-month period prior to the interview by survey participants.

Vital status follow-up and death causes

A total of 12 identifiers (including social security number, sex, and date of birth) were used to link NHANES III participants with the National Death Index to ascertain the vital status and the causes of death. The person-year (p*y) contribution from each participant was calculated as the time between the baseline examination and the date of death (if applicable) or December 31, 2010 (if still alive), whichever occurred first. The cause of death was determined using the underlying cause listed on the death certificate. The International Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Cause of Death (ICD) 10th revision was used to code the deaths into several main groups by cause. All deaths occurring prior to 1999 coded under the ICD-9 were recoded into the comparable ICD-10 codes. Certain contributing causes of death were coded in the multiple causes of death codes according to the coding rules. Death was classified as having hypertension as a contributing cause if the contributing or multiple causes of death fields had an ICD-9 code of 250 or an ICD-10 code of E10-E14.

Statistical analysis

We used the SAS (SAS 9.4, Research Triangle Park, NC) procedures for surveys with appropriate weighting and nesting variables to produce accurate national estimates and adjust for the oversampling of specific populations. The median survival times were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method. The death rate, or the number of deaths per 1000 person*years (hereafter as p*ys), was calculated separately for the low quartile, interquartile, and high quartile RBC folate groups. The estimates of the survival probability and cumulative incidence functions (CIFs) were estimated from Cox proportional hazard regression models for individuals with different levels of folate. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by visual inspection of plots of log [log (S)] against time, where S was the estimated survival function. The relatively small number of deaths prevented us from examining the data stratified by race and sex, but sex and race/ethnicity were included as covariates in all models. The Cox proportional regression does not yield valid results for a particular risk if failures from other causes are treated as censored, and competing risks, such as cancer, may result in a severe survivorship bias [40]. Therefore, we ran the SAS macro developed by Lin et al. [41] to estimate CIFs for participants with different folate levels as complements, and Gray’s method was used to assess the equality of CIFs [40]. To assess reverse causality, i.e., whether the observations were distorted by an underlying disease that might cause both abnormal values of RBC folate and increased risk of death, we repeated the steps described above but all deaths that occurred in first two years of the follow-up were excluded. Certain types of medications may also change the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of folate, and BMI was reported to be significantly associated with RBC folate levels [14]. However, these associations may also be parts of the causal pathway of the association under assessment; therefore, to prevent overadjustment, we adjusted these factors in sensitivity analyses instead of in the main analyses. Age played a crucial role in the association under investigation, and we examined the association among participants 70 years and older to assess the consistency across age. This was performed as part of the secondary analyses due to the compromised statistical power resulting from the reduced numbers of cause-specific deaths. To graphically illustrate the time dependence of the association, we plotted the CIFs against the follow-up year by the category of RBC folate.

Results

The average duration of follow-up was 11.7 years (standard error = 0.03), and the mean age at the baseline interview was 55.2 years. Similar to the general population when the baseline survey was conducted, 35.6% of the hypertensive adults were from middle-income families, and approximately 14% lived under the poverty line. Approximately 76.5% of the patients were white, and 3.9% were Mexican American, reflecting the racial and ethnic demographics of the United States in the early 1990s (Table 1).

Stratified by the level of RBC folate, almost 80% of study participants with high folate but less than 40% with low folate were 55 years or older (Table 2). More participants with high folate were from middle- or high-income families, and whites accounted for 87.92% of study participants with high folate in contrast to 63.45% of participants with low folate (p < 0.001). Adults with high RBC folate were also more likely to take vitamin B-12, food supplements, and medications; 26.48%, 29.09%, and 36.24% of patients with low, moderate, and high folate levels were on medications for endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases.

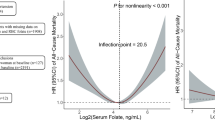

After 32,743.17 p*ys of follow-up, 1,192 deaths were recorded, 579 of which were from CVD. Survival time was significantly shorter among patients with high folate compared to their counterparts with low folate (Fig. 2) and almost two years shorter for all-cause death (12.45 vs. 10.44 years), CVD (13.65 vs. 11.66), stroke (13.56 vs. 11.71) and heart diseases (13.85 vs. 11.97). Consistent with the survival time, clear gradients of cardiovascular death rates were observed along with RBC folate levels, and CVD mortality was 13.04/1,000 p*ys, 16.95/1,000 p*ys, and 26.61/1000 p*ys for the groups with low, moderate and high folate, respectively (Fig. 3). After adjustment for the potential confounding factors including age, sex, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, vitamin B-12 supplementation, serum cotinine and Hcy, and CVD history assessed at baseline, the inverse association between mortality rates and folate was found to be J-shaped with statistical significance for heart diseases, acute myocardial infarction and all deaths with hypertension as a contributing cause but not stroke. No significant association was detected between low folate and the risk of cardiovascular death despite a suggestive increase in HRs of heart disease and myocardial infarction; the HR for CVD deaths among participants with high folate remained significantly higher than that among those with moderate folate. The adjusted HRs of CVD for patients with low, moderate, and high folate were 1.09 (0.94, 1.27), 1.00 (reference group), and 1.44 (1.31, 1.58), respectively. The corresponding HRs of myocardial infarction were 1.13 (0.86, 1.50), 1.00, and 2.13 (1.77, 2.57). Further adjustment for BMI and the use of medications for endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases did not significantly change the estimates (Online table). As supplemental analyses to assess reverse causality, exclusion of the deaths occurring in the first two years of follow-up weakened the association estimated from the main analyses, but the estimates remained statistically significant. The HRs of all CVD deaths combined, heart diseases, and acute myocardial infarction were 1.26 (1.15, 1.40), 1.33 (1.16, 1.51), and 1.65 (1.36, 2.01), respectively, for hypertensive patients with high folate relative to patients with moderate folate. The estimates among the elderly were also consistent with the overall estimation. The HRs of heart disease and acute myocardial infarction were 1.19 (1.05–1.34) and 1.49 (1.22–1.81), respectively, for hypertensive patients 70 years or older with high folate relative to patients with moderate folate (data not shown).

Survival time (median) by the level of red-blood cell folate, 2986 US adults aged 19 and older with hypertension, NHANES 1991–2010. AM Acute myocardial, CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, NHANES National Health Examination and Nutrition Survey, RBC red blood cell, Q quartile. 1Cardiovascular diseases included acute rheumatic fever and chronic rheumatic heart diseases (I00-I09), hypertensive heart disease (I11), hypertensive heart and renal disease (I13), acute myocardial infarction (I21-I22), other acute ischemic heart diseases (I24), atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (I25.0), all other forms of chronic ischemic heart disease (I20, I25.1-I25.9), acute and subacute endocarditis (I33), diseases of the pericardium and acute myocarditis (I30-I31, I40), heart failure (I50), all other forms of heart disease (I26-I28, I34-I38, I42-I49, I51), essential (primary) hypertension and hypertensive renal disease (I10, I12), cerebrovascular diseases (I60-I69), atherosclerosis (I70), aortic aneurysm and dissection (I71), other diseases of arteries, arterioles and capillaries (I72-I78), and other disorders of the circulatory system (I80-I99). The ICD 10 codes for acute myocardial infarction are I21-I22 and I60-I69 for stroke (cerebrovascular diseases). 2The median survival times were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier option in SAS PROC LIFETEST, and at the present time, the procedure is not able to integrate the survey design variables; therefore, the estimates of survival time were unadjusted and unweighted

Adjusted hazards ratio (95% CI) of dying from cardiovascular diseases, 2986 US adults aged 19 and older with hypertension, NHANES 1991–20101. AM Acute myocardial, CVD cardiovascular diseases, CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, NHANES the National Health Examination and Nutrition Survey, RBC red blood cell, R reference.1Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, family income, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, history of cardiovascular diseases, and supplementation of vitamin B12, serum cotinine and homocysteine. 2The ICD 10 codes for acute myocardial infarction are I21-I22, and those for stroke (cerebrovascular diseases) are I60-I69. 3The Ns and ns were presented as unweighted, but the rates were weighted

Consistent with the quantities obtained from Cox hazard regressions, there were clear separations of CIF curves, as the group with high folate had the highest probability of dying from CVD (Fig. 4). The separations between the groups started from the beginning of the follow-up, and the diverging trend continued towards the end of follow-up. The p-value of Gray’s test for equality of CIFs indicated significant differences (p < 0.01).

Cumulative incidence functions of CVDs by the level of red-blood cell folate, 2986 US adults aged 19 and older with hypertension, NHANES 1991–20101,2. CVD Cardiovascular diseases; NHANES the National Health Examination and Nutrition Survey, RBC red blood cell. 1The cumulative incidence functions were estimated using the SAS macro developed by Lin et al. [41]. The macro is not able to handle survey data; therefore, the graph was created without consideration of weighting and nesting variables. 2Cardiovascular diseases included acute rheumatic fever and chronic rheumatic heart diseases (I00-I09), hypertensive heart disease (I11), hypertensive heart and renal disease (I13), acute myocardial infarction (I21-I22), other acute ischemic heart diseases (I24), atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (I25.0), all other forms of chronic ischemic heart disease (I20, I25.1-I25.9), acute and subacute endocarditis (I33), diseases of the pericardium and acute myocarditis (I30-I31, I40), heart failure (I50), all other forms of heart disease (I26-I28, I34-I38, I42-I49, I51), essential (primary) hypertension and hypertensive renal disease (I10, I12), cerebrovascular diseases (I60-I69), atherosclerosis (I70), aortic aneurysm and dissection (I71), other diseases of arteries, arterioles and capillaries (I72-I78), and other disorders of the circulatory system (I80-I99)

Discussion

Serum folate has been commonly used in epidemiologic research examining the association between folate status and various health outcomes, yielding inconsistent and conflicting results [42, 43]. RBC folate reflects folate status in tissue and turnover during the preceding two to three months and is more reliable for assessing long-term folate status than serum folate [9]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated to be more robust in assessing the association between folate status and metabolic indicators [14, 44]. The current report is the first observational study to longitudinally examine the association between RBC folate and cardiovascular deaths among hypertensive adults sampled from a nationally representative sample. No statistical evidence emerged indicating an association between low RBC folate; instead, high RBC folate was found to be associated with increased hazards of CVD deaths relative to moderate RBC folate.

The biological mechanism underlying the association between high RBC folate and increased mortality from CVD remains to be illustrated. Excess RBC folate in persons with vitamin B-12 deficiency may mask anemia [45, 46]. It is well established that anemia, if overlooked, can significantly decrease the survivability of patients with pulmonary hypertension [47]. The increasing concerns of exposure to unmetabolized folic acid (UMFA), resulting from excessive folic acid intake beyond the liver’s metabolic capacity [45], may provide an additional clue for exploration. Folic acid is normally converted to tetrahydrofolate following uptake by the liver. If the body’s ability to convert folic acid is exceeded, UMFA will be found circulating in the blood [48]. Healthy adults responded to a high-dose folic acid supplement with increased UMFA concentrations. Among Brazilian adults, changes in cytokine mRNA expression and reduced number and cytotoxicity of natural killer (NK) cells were also observed [49], same with postmenopausal American women [50], and diabetic patients [51] with circulating UMFA. Compromised NK cytotoxicity was observed to be associated with autoimmunity [52] and a hyperinflammatory response [53], which was recently reported to be more prevalent in patients with severe forms of hypertension than in normotensive patients [54]. Additionally, the harmful effect of an imbalance between folate and vitamin B-12 status is likely to occur in vegetarians, certain ethnic minorities, and elderly individuals with poor vitamin B-12 absorption [45, 55], causing various metabolic disturbances [56]. Among nonpregnant fasting adults in a nationally representative sample from the more recent NHANES (2003-2006), Bird and coworkers observed a significant positive relation between RBC folate (P < 0.01) and BMI, waist circumference, serum triglycerides, and fasting plasma glucose [14]. The associations described by Bird et al might be part of the intermediate pathway of the association we observed. However, including BMI as an explanatory variable did not change the HR estimates meaningfully; therefore, the association between RBC folate and risk of CVD death may be independent of BMI and other cardiovascular indicators assessed in Bird et al.’s study. Adults with high RBC folate were also more likely to be on medications for endocrine, nutritional, and CVD. However, controlling for medication use did not change the estimates either.

It is of interest to note that high RBC folate may not necessarily be an indicator of supraphysiologic concentrations or insufficient levels of bioavailability from the tissue. An experimental study showed that folate deficiency led to a significant upregulation in folate uptake in human intestinal epithelial cells accompanied by a parallel increase in reduced folate carrier protein and mRNA concentrations [57]. The upregulation of transepithelial transport of folic acid in intestinal epithelial cells suggests the possibility that higher cellular folate concentrations in RBCs coexist with overall folate deficiency. Indeed, high serum folate was frequently reported to be associated with anemia and macrocytosis, especially among seniors with low vitamin B-12 status [46], indicating that the relationship between cellular folate concentrations in RBCs and overall folate status may be potentially complex under pathological conditions. Using serum folate concentrations below <10 nmol/L as the cutoff, Pfeiffer and coworkers estimated that the prevalence of folate deficiency was as high as 24% among the populations sampled for the 1988–1994 survey [32], the prefortification period overlapped with the baseline survey of the current analyses. Speculatively, high RBC folate in the present study may indicate folate deficiency. However, adults with high RBC folate in the current study were less likely to be heavy smokers than adults with low RBC folate in the current study, apparently conflicting with the speculation that high RBC indicates folate deficiency. Further investigations are warranted to assess the biological and clinical implications of high RBC folate and its relationship with the overall folate status.

The limitations of the current study are considerable. Small numbers of disease-specific deaths prevented us from investigating cause-specific relationships stratified by sociodemographic factors. Selection bias is a major limitation as well. Although the study population was selected from a nationally representative sample, it excluded institutionalized patients. CVD is more prevalent among institutionalized elderly patients. Therefore, caution must be exercised when generalizing the conclusions of the current study. It would be preferable to have repeated measurements of RBC folate. Mandatory fortification of cereal grain products with folic acid was authorized in 1996 and fully implemented in 1998 in the United States [58]. The current analyses covered both the prefortification (1991–1998) and postfortification periods (1999–2010). A sharply increasing linear trend was observed in folate concentrations, and assay-adjusted RBC folate concentrations in the postfortification period were 50% higher than those of prefortification period [58]. Therefore, the average RBC folate level during the follow-up period must be much higher than that measured during the baseline survey, and the interquartile range might be smaller during postfortification than during prefortification due to left-skewing of RBC folate distribution. The diminished variations in RBC folate likely attenuated the association examined. Using serum Hcy concentration to proxy the MTHFR C677T genotype might not be sufficient to describe the impact of genetic predisposition.

The current study has strengths as well. The richness of NHANES allows us to delineate the relation after adjustment for a wide array of covariates. Compared with previous studies, the participants of NHANES III were selected from the community-dwelling population, extending the observations from clinical populations to a relatively healthy one. A unique feature of this study is that baseline information was collected prior to fortification of folic acid in foods; therefore, we have a population with relatively large variation at baseline.

UMFA has been found among almost all segments of the population [59], from the cord blood of newly delivered infants [60] to older US adults [61]. However, little has been done at the population level to assess the overall impact of UMFA. As an addition to a growing body of evidence indicating an unwelcome outcome, our study calls for a more rigorous assessment of the relationship between folate level and conditions beyond neural tube defects, especially among populations with a high CVD risk.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is responsible only for the initial data.

References

Schwartz SM, Siscovick DS, Malinow MR, Rosendaal FR, Beverly RK, Hess DL, et al. Myocardial infarction in young women in relation to plasma total homocysteine, folate, and a common variant in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene. Circulation. 1997;96:412–7.

Selhub J, Jacques PF, Bostom AG, D’Agostino RB, Wilson PW, Belanger AJ, et al. Association between plasma homocysteine concentrations and extracranial carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:286–91.

Loria CM, Ingram DD, Feldman JJ, Wright JD, Madans JH. Serum folate and cardiovascular disease mortality among US men and women. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3258–62.

Morrison HI, Schaubel D, Desmeules M, Wigle DT. Serum folate and risk of fatal coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1996;275:1893–6.

Folsom AR, Nieto FJ, McGovern PG, Tsai MY, Malinow MR, Eckfeldt JH, et al. Prospective study of coronary heart disease incidence in relation to fasting total homocysteine, related genetic polymorphisms, and B vitamins: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 1998;98:204–10.

Voutilainen S, Rissanen TH, Virtanen J, Lakka TA, Salonen JT. Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Risk Factor S. Low dietary folate intake is associated with an excess incidence of acute coronary events: The Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Circulation. 2001;103:2674–80.

Huang YC, Lee MS, Wahlqvist ML. Prediction of all-cause mortality by B group vitamin status in the elderly. Clin Nutr. 2012;31:191–8.

Xun P, Liu K, Loria CM, Bujnowski D, Shikany JM, Schreiner PJ, et al. Folate intake and incidence of hypertension among American young adults: a 20-y follow-up study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:1023–30.

Hung J, Beilby JP, Knuiman MW, Divitini M. Folate and vitamin B-12 and risk of fatal cardiovascular disease: cohort study from Busselton, Western Australia. BMJ. 2003;326:131.

Dangour AD, Breeze E, Clarke R, Shetty PS, Uauy R, Fletcher AE. Plasma homocysteine, but not folate or vitamin B-12, predicts mortality in older people in the United Kingdom. J Nutr. 2008;138:1121–8.

Chasan-Taber L, Selhub J, Rosenberg IH, Malinow MR, Terry P, Tishler PV, et al. A prospective study of folate and vitamin B6 and risk of myocardial infarction in US physicians. J Am Coll Nutr. 1996;15:136–43.

Roswall N, Olsen A, Christensen J, Hansen L, Dragsted LO, Overvad K, et al. Micronutrient intake in relation to all-cause mortality in a prospective Danish cohort. Food Nutr Res. 2012;56:5466.

Peng Y, Dong B, Wang Z. Serum folate concentrations and all-cause, cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality: a cohort study based on 1999-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Int J Cardiol. 2016;219:136–42.

Bird JK, Ronnenberg AG, Choi SW, Du F, Mason JB, Liu Z. Obesity is associated with increased red blood cell folate despite lower dietary intakes and serum concentrations. J Nutr. 2015;145:79–86.

MacKenzie KE, Wiltshire EJ, Gent R, Hirte C, Piotto L, Couper JJ. Folate and vitamin B6 rapidly normalize endothelial dysfunction in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics. 2006;118:242–53.

Mierzecki A, Kloda K, Bukowska H, Chelstowski K, Makarewicz-Wujec M, Kozlowska-Wojciechowska M. Association between low-dose folic acid supplementation and blood lipids concentrations in male and female subjects with atherosclerosis risk factors. Med Sci Monit. 2013;19:733–9.

Wu CJ, Wang L, Li X, Wang CX, Ma JP, Xia XS. [Impact of adding folic acid, vitamin B(12) and probucol to standard antihypertensive medication on plasma homocysteine and asymmetric dimethylarginine levels of essential hypertension patients]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2012;40:1003–8.

Aghamohammadi V, Gargari BP, Aliasgharzadeh A. Effect of folic acid supplementation on homocysteine, serum total antioxidant capacity, and malondialdehyde in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Nutr. 2011;30:210–5.

Gargari BP, Aghamohammadi V, Aliasgharzadeh A. Effect of folic acid supplementation on biochemical indices in overweight and obese men with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pr. 2011;94:33–38.

Schnyder G, Roffi M, Flammer Y, Pin R, Hess OM. Effect of homocysteine-lowering therapy with folic acid, vitamin B12, and vitamin B6 on clinical outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention: the Swiss Heart study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:973–9.

Zhao F, Li JP, Wang SY, Guan DM, Ge JB, Hu J, et al. The effect of baseline homocysteine level on the efficacy of enalapril maleate and folic acid tablet in lowering blood pressure and plasma homocysteine. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2008;88:2957–61.

Fu J, Tang HQ, Qin XH, Mao GY, Tang GF. Efficacy of enalapril combined with folic acid in lowering blood pressure and plasma homocysteine level. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2009;89:2179–83.

Huo Y, Li J, Qin X, Huang Y, Wang X, Gottesman RF, et al. Efficacy of folic acid therapy in primary prevention of stroke among adults with hypertension in China: the CSPPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:1325–35.

Wang L, Li H, Zhou Y, Jin L, Liu J. Low-dose B vitamins supplementation ameliorates cardiovascular risk: a double-blind randomized controlled trial in healthy Chinese elderly. Eur J Nutr. 2015;54:455–64.

Lonn E, Yusuf S, Arnold MJ, Sheridan P, Pogue J, Micks M, et al. Homocysteine lowering with folic acid and B vitamins in vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1567–77.

Bonaa KH, Njolstad I, Ueland PM, Schirmer H, Tverdal A, Steigen T, et al. Homocysteine lowering and cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1578–88.

Toole JF, Malinow MR, Chambless LE, Spence JD, Pettigrew LC, Howard VJ, et al. Lowering homocysteine in patients with ischemic stroke to prevent recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, and death: the Vitamin Intervention for Stroke Prevention (VISP) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:565–75.

Cole BF, Baron JA, Sandler RS, Haile RW, Ahnen DJ, Bresalier RS, et al. Folic acid for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2007;297:2351–9.

Albert CM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, Zaharris E, MacFadyen J, Danielson E, et al. Effect of folic acid and B vitamins on risk of cardiovascular events and total mortality among women at high risk for cardiovascular disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299:2027–36.

Lange H, Suryapranata H, De Luca G, Borner C, Dille J, Kallmayer K, et al. Folate therapy and in-stent restenosis after coronary stenting. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2673–81.

Ebbing M, Bonaa KH, Nygard O, Arnesen E, Ueland PM, Nordrehaug JE, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality after treatment with folic acid and vitamin B12. JAMA. 2009;302:2119–26.

Pfeiffer CM, Hughes JP, Lacher DA, Bailey RL, Berry RJ, Zhang M, et al. Estimation of trends in serum and RBC folate in the U.S. population from pre- to postfortification using assay-adjusted data from the NHANES 1988-2010. J Nutr. 2012;142:886–93.

Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Du M, White E, Giovannucci EL. Trends in dietary supplement use among US adults From 1999-2012. JAMA. 2016;316:1464–74.

Li Y, Dai Q, Ekperi LI, Dehal A, Zhang J. Fish consumption and severely depressed mood, findings from the first national nutrition follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2011;190:103–9.

Lainscak M, Farkas J, Frantal S, Singer P, Bauer P, Hiesmayr M, et al. Self-rated health, nutritional intake and mortality in adult hospitalized patients. Eur J Clin Invest. 2014;44:813–24.

Frosst P, Blom HJ, Milos R, Goyette P, Sheppard CA, Matthews RG, et al. A candidate genetic risk factor for vascular disease: a common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Nat Genet. 1995;10:111–3.

Moll S, Varga EA. Homocysteine and MTHFR mutations. Circulation. 2015;132:e6–e9.

Holmes MV, Newcombe P, Hubacek JA, Sofat R, Ricketts SL, Cooper J, et al. Effect modification by population dietary folate on the association between MTHFR genotype, homocysteine, and stroke risk: a meta-analysis of genetic studies and randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378:584–94.

Qin X, Li J, Cui Y, Liu Z, Zhao Z, Ge J, et al. Effect of folic acid intervention on the change of serum folate level in hypertensive Chinese adults: do methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and methionine synthase gene polymorphisms affect therapeutic responses? Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2012;22:421–8.

Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–54.

Lin GX, So Y, Johnston G. Analyzing Survival Data with Competing Risks Using SAS® Software. SAS Global Forum 2012 Statistics and Data Analysis. Cary NC 2012.

Larsson SC, Giovannucci E, Wolk A. Folate and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:64–76.

Ericson U, Sonestedt E, Gullberg B, Olsson H, Wirfalt E. High folate intake is associated with lower breast cancer incidence in postmenopausal women in the Malmo Diet and Cancer cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:434–43.

Wolpin BM, Wei EK, Ng K, Meyerhardt JA, Chan JA, Selhub J, et al. Prediagnostic plasma folate and the risk of death in patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3222–8.

Smith AD, Kim YI, Refsum H. Is folic acid good for everyone? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:517–33.

Morris MS, Jacques PF, Rosenberg IH, Selhub J. Folate and vitamin B-12 status in relation to anemia, macrocytosis, and cognitive impairment in older Americans in the age of folic acid fortification. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:193–200.

Krasuski RA, Hart SA, Smith B, Wang A, Harrison JK, Bashore TM. Association of anemia and long-term survival in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2011;150:291–5.

Patanwala I, King MJ, Barrett DA, Rose J, Jackson R, Hudson M, et al. Folic acid handling by the human gut: implications for food fortification and supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:593–9.

Paniz C, Bertinato JF, Lucena MR, De Carli E, Amorim P, Gomes GW, et al. A daily dose of 5 mg folic acid for 90 days is associated with increased serum unmetabolized folic acid and reduced natural killer cell cytotoxicity in healthy Brazilian adults. J Nutr. 2017;147:1677–85.

Troen AM, Mitchell B, Sorensen B, Wener MH, Johnston A, Wood B, et al. Unmetabolized folic acid in plasma is associated with reduced natural killer cell cytotoxicity among postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2006;136:189–94.

Ulrich CM, Potter JD. Folate supplementation: too much of a good thing? Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15:189–93.

Bayer AL, Fraker CA. The folate cycle as a cause of natural killer cell dysfunction and viral etiology in type 1 diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:315.

Shabrish S, Kelkar M, Chavan N, Desai M, Bargir U, Gupta M, et al. Natural killer cell degranulation defect: a cause for impaired nk-cell cytotoxicity and hyperinflammation in fanconi anemia patients. Front Immunol. 2019;10:490.

Junqueira CLC, Magalhaes MEC, Brandao AA, Ferreira E, Cyrino F, Maranhao PA, et al. Microcirculation and biomarkers in patients with resistant or mild-to-moderate hypertension: a cross-sectional study. Hypertens Res. 2018;41:515–23.

Selhub J, Morris MS, Jacques PF. In vitamin B12 deficiency, higher serum folate is associated with increased total homocysteine and methylmalonic acid concentrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19995–20000.

Morris MS, Jacques PF, Rosenberg IH, Selhub J. Circulating unmetabolized folic acid and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate in relation to anemia, macrocytosis, and cognitive test performance in American seniors. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1733–44.

Subramanian VS, Chatterjee N, Said HM. Folate uptake in the human intestine: promoter activity and effect of folate deficiency. J Cell Physiol. 2003;196:403–8.

Crider KS, Bailey LB, Berry RJ. Folic acid food fortification-its history, effect, concerns, and future directions. Nutrients. 2011;3:370–84.

Pfeiffer CM, Sternberg MR, Fazili Z, Yetley EA, Lacher DA, Bailey RL, et al. Unmetabolized folic acid is detected in nearly all serum samples from US children, adolescents, and adults. J Nutr. 2015;145:520–31.

Obeid R, Kirsch SH, Kasoha M, Eckert R, Herrmann W. Concentrations of unmetabolized folic acid and primary folate forms in plasma after folic acid treatment in older adults. Metabolism. 2011;60:673–80.

Bailey RL, Mills JL, Yetley EA, Gahche JJ, Pfeiffer CM, Dwyer JT, et al. Unmetabolized serum folic acid and its relation to folic acid intake from diet and supplements in a nationally representative sample of adults aged > or =60 y in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:383–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Twum, F., Morte, N., Wei, Y. et al. Red blood cell folate and cardiovascular deaths among hypertensive adults, an 18-year follow-up of a national cohort. Hypertens Res 43, 938–947 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0482-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0482-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association of dietary intake of folate, serum folate, and red blood cell folate with mortality risk in patients with depression: a population-based longitudinal cohort study

Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition (2025)

-

Association between RBC folate and odds of osteoarthritis in adults aged 40–60 years

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Association between RBC folate and diabetic nephropathy in Type2 diabetes mellitus patients: a cross-sectional study

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Non-linear associations of serum and red blood cell folate with risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in hypertensive adults

Hypertension Research (2023)