Abstract

Renovascular hypertension (RVH) is one of the most common causes of secondary hypertension and can result in resistant hypertension. RVH is associated with an increased risk for progressive decline in renal function, cardiac destabilization syndromes including “flash” pulmonary edema, recurrent congestive heart failure, and cerebrocardiovascular disease. The most common cause of renal artery stenosis (RAS) is atherosclerotic lesions, followed by fibromuscular dysplasia. The endovascular technique of percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty (PTRA) with or without stenting is one of the standard treatments for RAS. Randomized controlled trials comparing medical therapy with PTRA to medical therapy alone have failed to show a benefit of PTRA; however, the subjects of these randomized clinical trials were limited to atherosclerotic RAS patients, and patients with the most severe RAS, who would be more likely to benefit from PTRA, might not have been enrolled in these trials. This review compares international guidelines related to PTRA, reevaluates the effects of PTRA treatment on blood pressure and renal and cardiac function, discusses strategies for the management of RVH patients, and identifies factors that may predict which patients are most likely to benefit from PTRA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Renovascular hypertension (RVH) is one of the most common causes of secondary hypertension and can result in resistant (refractory) hypertension. RVH is associated with an increased risk of progressive decline in renal function, cardiac destabilization syndromes including “flash” pulmonary edema, recurrent congestive heart failure (CHF), and cerebrocardiovascular disease. The most common cause of renal artery stenosis (RAS) is atherosclerotic lesions (ARAS), followed by fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD). Although their prevalence is lower, a variety of other causes, such renal artery dissection and embolic disease, can produce the same symptoms [1].

The endovascular technique of percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty (PTRA) with or without stenting is one of the standard treatments for RAS. Despite prospective clinical trial evidence for the safety and efficacy of PTRA with stenting [2,3,4], randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown no difference in outcomes between medical therapy plus PTRA and medical therapy alone [5,6,7]. These negative trials led to the widespread impression that PTRA is not beneficial, and evaluation of renal blood flow makes no sense. However, these trials had significant design flaws, and the selection of patients for PTRA is a controversial topic, as acknowledged by a comparative effectiveness review of management strategies for RAS by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [8, 9].

In this review, we compare international guidelines related to PTRA, reevaluate the effects of PTRA treatment on blood pressure (BP) and renal and cardiac function, discuss strategies for the management of RVH patients, and identify factors that may predict which patients are most likely to benefit from PTRA.

Indications for revascularization in the guidelines

Likely to benefit from revascularization

Most guidelines consistently recommend that the patients most likely to benefit from revascularization have hemodynamically significant RAS and (1) FMD with hypertension, (2) resistant hypertension with failure of or intolerance to antihypertensive medication, (3) recurrent heart failure or sudden-onset “flash” pulmonary edema, (4) progressive renal function decline due to bilateral lesions or solitary kidney, or (5) refractory acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (Table 1) [10,11,12,13]. The recommendations from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions present actual figures of kidney function (i.e., estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) level or kidney size) and stenosis severity (pressure gradient).

Unlikely to benefit from revascularization

When evaluating an RAS patient with any symptoms, it is important to diagnose whether the symptoms are caused by renal hypoperfusion. In some cases, RAS is found incidentally on routine abdominal imaging when evaluating a patient for other problems. There is no evidence or consensus on the treatment of asymptomatic RAS patients [10]. ARAS patients with controlled BP and stable renal function on low-dose antihypertensive drugs are unlikely to benefit from PTRA. Therefore, optimizing medical therapy should be the initial step for most RAS patients. A lack of response to medical therapy is often an important element in deciding on revascularization. Patients with severely reduced renal function who are unlikely to benefit from PTRA include those with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 5 and a pole-to-pole kidney size <7.0 cm or those receiving hemodialysis therapy for ≥3 months [10].

Effects of PTRA on BP control and kidney and cardiac function

Limitations of previous RCTs

Prospective RCTs reported between 1998 and 2017 failed to identify additional benefits for ARAS from endovascular stent revascularization when added to medical therapy [5,6,7]. The subjects of these RCTs were limited to ARAS patients.

The Angioplasty and Stent for Renal Artery Lesions (ASTRAL) study included 806 ARAS patients [5]. Only 60% of the subjects in the intervention group had severity of stenosis >60%, and the rate of periprocedural complications (9%) was much higher than that in other reported studies. Patients were only enrolled in this trial if their clinician was uncertain as to whether PTRA would be of clinical benefit, and patients who were most likely to benefit from PTRA might have been excluded from the study.

A similar limitation was found in the STent placement and BP and lipid-lowering for the prevention of progression of renal dysfunction caused by Atherosclerotic ostial stenosis of the Renal artery (STAR) trial, which included 140 ARAS patients with creatinine clearance <80 mL/min/1.73 m2 with ostial stenosis ≥50% and controlled BP <140/90 mmHg [6]. In this study, all patients had controlled BP, and a considerable number of participants (32% of the medication group and 34% of the stent group) had moderate (50–70%) stenosis.

The Cardiovascular Outcomes in Renal Atherosclerotic Lesions (CORAL) study enrolled 947 hypertensive patients with ARAS, and the original study protocol defined eligible candidates as those with systolic BP ≥155 mmHg despite taking ≥2 antihypertensive drugs or those with CKD defined as eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 [7]. However, because of slow enrollment, these original inclusion criteria were later relaxed, and participants without hypertension or CKD were also recruited. Mean renal stenosis defined by core laboratory parameters in the stenting plus medical therapy group and medical therapy group was present in 67.3% and 66.9% of subjects, respectively, which suggests that a significant proportion of ARAS patients with mild-to-moderate stenosis were included. The number of antihypertensive medications was 2.1 ± 1.6 at baseline and increased in both the groups to 3.5 ± 1.4 in the medical therapy group and 3.3 ± 1.5 in the stenting group at the completion of the trial. Both groups had similar decreases in systolic BP (15.6 ± 25.8 mmHg in the medical therapy group; 16.6 ± 21.2 mmHg in the stent group), implying that antihypertensive therapy was not optimized at the initiation of treatment.

The RAndomized, multi-center, prospective study comparing best medical treatment versus best medical treatment plus renal artery stenting in patients with hemoDynamically relevant atherosclerotic renal ARtery stenosis (RADAR) study included 86 ARAS patients and aimed to evaluate the clinical impact of PTRA stenting on eGFR in patients with hemodynamically significant ARAS based on duplex ultrasonographic patient screening [14]. However, because of slow enrollment, this study was terminated early after the inclusion of 86 of the scheduled 300 patients (28.7%), and the outcomes of PTRA were similar to those of medical treatment.

As frequently pointed out by other researchers [8, 15,16,17,18], all these recent RCTs have significant flaws, such as variability in inclusion and exclusion criteria, inconsistent definitions of improvement, or mixtures of hypertension and renal function endpoints. Further, patients selected for RCTs represent “mild RVH” with easily achieved BP control, relatively preserved renal function, and absence of pulmonary edema. On the other hand, these results may illuminate an important message that, for patients with mild-to-moderate ARAS (<70% diameter stenosis), according to clinical practice guidelines, multifactorial medical therapy consisting of an angiotensin receptor-blocking agent, statin, antiplatelet therapy, smoking cessation, and management of diabetes is preferred.

BP-lowering effect of PTRA

It should be noted that the BP-lowering effect was not defined as the primary outcome in the ASTRAL, STAR, CORAL, and RADAR trials. A meta-analysis of RCTs including 4 studies (n = 809) and comparison of balloon angioplasty with medical therapy in hypertensive patients with ARAS (>50% diameter stenosis) demonstrated a small improvement in diastolic BP in the angioplasty group [mean difference (MD) −2.00 mmHg, 95% confidence interval (CI) −3.72 to −0.27; p = 0.02], while a meta-analysis of 5 studies (n = 1743) did not find a significant improvement in systolic BP (MD −1.07 mmHg, 95% CI −3.45 to 1.30; p = 0.38). On the other hand, the pooled results from 3 trials (n = 1717) found that, at the end of follow-up, there was a significant decrease in the number of antihypertensive drugs in the angioplasty group compared to the medical treatment group (MD −0.18, 95% CI −0.34 to −0.03; p = 0.02) [16]. Therefore, it would still be unwise to conclude that the BP-lowering effect of PTRA is insubstantial.

A nonrandomized series of complex ARAS patients showed BP improvement by PTRA [19]; however, the BP response in most of these previous trials was diagnosed based on office BP, and evidence concerning the effects of PTRA on out-of-office BP is limited. Eight nonrandomized studies with unilateral or bilateral ARAS have provided information on the effectiveness of PTRA in lowering out-of-office BP (Table 2) [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. One of these studies evaluated BP response using home BP monitoring, and the others used ambulatory BP monitoring devices. Most of these studies were small and had a short duration of follow-up; however, studies including >50 patients and having a relatively longer duration of follow-up have shown a certain level of BP reduction.

Renoprotective effect of PTRA

Restoring blood flow to an ischemic kidney beyond vascular occlusion or stenosis seems to provide an obvious means to restore kidney function; however, the strength of evidence for a renoprotective effect of PTRA is not so strong. There have been several RCTs in which the renal outcome was defined as the primary outcome; however, the reported indexes of renal function were heterogeneous (Table 3) [5,6,7, 14, 28, 29]. The STAR trial, in which the primary endpoint was defined as a >20% decline in creatinine clearance, reported serum creatinine at either the end of the 2-year follow-up or when participants reached the primary endpoint [6]. The ASTRAL trial reported the results of serum creatinine concentration for each year during the 5-year follow-up period [5]. The RADAR trial reported changes in eGFR after 12 months [14], and the CORAL trial reported progressive renal insufficiency [7]. In all of these RCTs, there was no significant difference in serum creatinine, creatinine clearance, worsening renal failure, or progressive renal insufficiency between the angioplasty and medical treatment groups (Table 3). One RCT found a significantly higher prevalence of worsening renal function in the PTRA group, defined as an increase in serum creatinine level of ≥20% at the end of follow-up (p < 0.001) [28]. A meta-analysis including 3 trials (n = 725) identified a statistically nonsignificant decrease in serum creatinine in the angioplasty group compared to the medical treatment group (MD −7.99 mmol/L, 95% CI −22.6 to 6.62; p = 0.28) [16].

A nonrandomized series of complex ARAS patients reported a renoprotective (or not worsening) effect of PTRA [30,31,32,33,34], and in some end-stage renal disease patients, successful PTRA permitted discontinuation of hemodialysis treatment [35, 36]. These observations indicate that some patients certainly obtain a major clinical benefit from successful PTRA; however, many other series of patients with various levels of renal dysfunction reported little change on average after PTRA [37].

In most of these previous trials, renal function was diagnosed based on serum creatinine level or eGFR. It is recommended that renal function should be evaluated based not only on eGFR but also on albuminuria and/or proteinuria [38]; however, there appears to be no solid data on the decrease in albuminuria or proteinuria after PTRA. A 1-year follow-up of 117 patients with successful PTRA demonstrated significant improvement in morning home systolic BP (−12 ± 24 mmHg) and diastolic BP (−4 ± 10 mmHg) (both p < 0.001) but no significant change in eGFR (46.2 ± 19.4 to 46.4 ± 10.2 ml/min/1.73 m2, p = 0.98), urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio [3.2 (1.1–17.8) to 4.3 (1.0–26.4) mg/mmol, p = 0.41], or protein/creatinine ratio [0 (0–44.8) to 10.9 (0–58.1) mg/mmol, p = 0.08] [39].

Cardioprotective effect of PTRA

There was low strength of evidence for cardiovascular risk reduction by PTRA [40]. In RCTs, the rates of cardiovascular events were similar between patients treated with angioplasty and those treated with medical therapy [5, 7, 41]. However, as described above, patients who would likely benefit from PTRA, that is, those with very severe stenosis and uncontrolled hypertension or recurrent sudden-onset pulmonary edema, were unlikely to be enrolled in these RCTs.

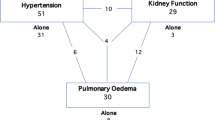

There have been several observational trials suggesting that the patients who are more likely to improve are those with cardiac destabilization syndromes after revascularization. Pulmonary edema was reported to be a risk factor for adverse outcomes in 467 ARAS patients, and compared to medical treatment, revascularization was associated with a reduced risk of death (hazard ratio 0.43, 95% CI, 0.20–0.91; p = 0.01) [42]. In 48 refractory hypertensive patients with severe ARAS (stenosis diameter >70%) who presented with ACS or decompensated heart failure, successful PTRA improved angina class without coronary revascularization (3.1 ± 0.8 to 1.5 ± 0.9, p < 0.05) in ACS patients and heart failure status in heart failure patients [New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, 2.8 ± 0.9 to 1.7 ± 1.2, p < 0.05] at 24 h after PTRA [43]. Similar findings were reported in 39 RAS patients (stenosis diameter >70%) with recurrent episodes of CHF and/or flash pulmonary edema, in which successful PTRA resulted in a significant decrease in the number of hospital admissions due to heart failure as well as the severity of heart failure; NYHA class decreased from 2.9 ± 0.9 to 1.5 ± 0.9 [44].

Left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy is an established risk factor for worse outcomes, and a meta-analysis reported that ARAS patients had an increased likelihood of LV hypertrophy [45]. LV hypertrophy may be reversed by treatment, and prospective studies in hypertensive cohorts have shown an association between regression of LV hypertrophy and reduced cardiovascular complications [46, 47]. In both ARAS [45, 48] and FMD [48], PTRA produces a decrease in LV mass; however, in ARAS, in-treatment regression or continued absence of LV hypertrophy seemed not to be associated with reduced risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes [48].

Better approach to determining PTRA treatment

In most cases of RVH, the first goal of treatment is to reduce BP and the morbidity and mortality associated with elevated BP. The second goal is to protect the hemodynamics and function of the kidneys. Finally, in the case of uncontrolled heart failure, the goal is improvement of cardiac disturbance syndromes, including flash pulmonary edema. However, especially in ARAS, RVH is heterogeneous and progressive in practice, and many RVH patients also have other comorbidities, such as essential hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia, which adversely affect renal function and contribute to therapy-resistant hypertension. Therefore, distinguishing between benign complications and actual RVH and ischemic nephropathy is difficult. However, there has been increasing evidence concerning predictors that may be able to identify RAS patients who will benefit from PTRA.

Before PTRA

BP evaluation

Current international guidelines recommend out-of-office BP measurement in clinical practice [12, 13, 49]. Out-of-office BP measurement using home BP or ambulatory BP monitoring seems to be crucial when PTRA treatment is being considered. Ambulatory BP monitoring was performed in 191 RAS patients with ostial stenosis diameter ≥70% before and 1 year after PTRA and found that high baseline BP could be a predictor of better BP reduction [50]. This finding was confirmed in 72 ARAS patients (mean stenosis diameter, 78 ± 10%) with uncomplicated resistant hypertension defined as daytime ambulatory BP >135/85 mmHg, despite at least 3 antihypertensive drugs including a diuretic. Baseline daytime ambulatory BP was 157 ± 16/82 ± 10 mmHg, and at a mean 2 months of follow-up after PTRA, BP had decreased by 14.0 ± 17.3/6.4 ± 8.7 mmHg, despite a decrease in the number of antihypertensive medications from 4.0 ± 1.0 to 3.6 ± 1.4. Furthermore, it was found that high baseline ambulatory daytime systolic BP was an independent predictor of BP reduction (odds ratio 0.94, 95% CI: 0.90–0.99; p = 0.025) [27]. These results suggest that a better BP response to PTRA can be expected in ARAS patients with true resistant hypertension.

Home BP was measured in 126 RVH patients (22% FMD patients) before and 1 year after PTRA, demonstrating that, although most patients were diagnosed with uncontrolled morning home BP at baseline, at 1 year after PTRA, the prevalence of masked hypertension and uncontrolled hypertension was 32.5% and 6.4%, respectively [26]. This disproportional serial reduction between office and home BP also supports the need for out-of-office BP measurements.

Assessment of renal function

RVH patients showing a rapid renal functional decline are considered suitable candidates for PTRA treatment. Clear cutoff values to predict an improvement in renal function after PTRA have not been established, but the slope of the reciprocal serum creatinine plot [51], annual rate of eGFR decline [52], and degree of serum creatinine elevation 6 months before PTRA [42, 53] were reported to be useful indices for predicting the clinical course after PTRA.

Before consideration of PTRA treatment, renal function should be evaluated based on both eGFR and albuminuria/proteinuria. PTRA has limited benefit for patients with established long-term loss of eGFR, and decreased pretreatment eGFR and/or increased albuminuria/proteinuria is associated with an increased risk of worse outcomes after PTRA [39, 54,55,56]. Both eGFR and albuminuria/proteinuria were evaluated in 139 ARAS patients before and 1 year after PTRA, and a significant divergent response of eGFR changes according to the presence/absence of pretreatment albuminuria/proteinuria was found in those with a baseline eGFR of <45. In ARAS patients without albuminuria/proteinuria, PTRA treatment may have the ability to stabilize or improve eGFR, and its improvement could be expected even in those with a pretreatment eGFR of <30 [39]. In a post hoc study of the CORAL trial, patients with low pretreatment albuminuria in the angioplasty group showed better outcomes than those in the medical therapy group, but this was not observed in patients with high albuminuria [57]. These results suggest that ARAS patients without pretreatment albuminuria/proteinuria may be ideal candidates for PTRA treatment.

Imaging tests: renal ultrasonography and renal resistive index (RI)

The diagnosis of RVH is based on the demonstration of RAS and is therefore dependent upon imaging. Recent advances in noninvasive vascular imaging allow more frequent detection and precise diagnostic assessment using Doppler ultrasonography, computed tomography angiography (CTA), and magnetic resonance angiography.

Duplex Doppler renal ultrasonography is relatively inexpensive and suitable as an initial imaging tool. This can provide both functional and structural assessment and is also suitable for serial studies to determine progression and/or restenosis within the affected kidneys. Peak systolic velocity (PSV) >200 cm/s at the site of stenosis is associated with 95% sensitivity and 90% specificity for >50% stenosis, and a ratio of renal artery to aortic PSV >3.5 has 92% sensitivity for >60% stenosis [10, 58]. It must be emphasized that, in the diagnosis of FMD, it is important to image the renal artery in its entirety from the origin to the kidney parenchyma. As a practical matter, limitations of this technique include dependence upon operator skills and patient body build, and thus the precision of testing may vary widely between institutions. Evaluation of kidney morphology should include not only kidney size but also anatomical structure because functional characterization of the renal parenchyma distal to RAS may help predict revascularization outcomes. It has been suggested that renal function would not be expected to improve after revascularization in cases of atrophic kidney size (<7 cm) [59], thinning of the renal parenchyma [50], or smaller parenchymal volume to radioisotope-assessed single-kidney GFR [60].

The renal RI, measured by Doppler ultrasonography, is defined as [PSV minus minimum end-diastolic velocity]/PSV. In essential hypertensive patients, a higher RI obtained in proximal segmental arteries has been reported to be correlated with the presence of hypertensive organ damage [61] and to predict poor cardiovascular and renal outcomes [62]. High RI (>0.8) has been suggested to be associated with a worse renal outcome and with poor BP response to revascularization [63]. Several observational studies found similar findings, and low RI has been proposed as a marker of likely benefit from PTRA [64, 65]. However, this has not been observed universally [39, 66, 67].

FMD or ARAS

The treatment strategy for RVH patients with ARAS differs from that for patients with FMD. The BP response after PTRA is better in FMD [26], and cure for hypertension defined as removal of all antihypertensive therapy can be expected in considerable cases. The likelihood of cure depends on factors such as the age of the patient and the duration and severity of hypertension [68]. Clinicians should consider PTRA, especially for younger FMD subjects with hypertension, because without revascularization, many of them will require lifelong therapy, and PTRA may limit the need for ongoing medical therapy.

PTRA/angiography

Digital subtraction angiography is the gold standard for characterizing RAS lesions and is usually combined with endovascular procedures, including dilation and stent placement. The precise advantages and characteristics of various PTRA/angiography methods are beyond the scope of this review.

Studies of human subjects with translesional pressure gradients indicate that an aortic–renal pressure gradient of 10–20% is necessary to detect renin release [69], which corresponds to a translesional peak gradient of at least 20–25 mmHg and luminal stenosis of at least 70% [70]. Therefore, PTRA treatment has little effect on patients with mild-to-moderate RAS.

A 99% stenotic lesion, or “string of beads sign,” may be easy to identify, but more commonly, there is mild-to-moderate aorto-ostial stenosis, whose hemodynamic consequences are uncertain. In FMD, accurate visual assessment of the degree of stenosis is not possible with multifocal lesions, and the presence of significant beading may not be associated with a hemodynamically significant gradient. Therefore, translesional pressure gradient measurement is recommended to assess the hemodynamic significance of stenosis [71], and a pressure gradient >10% of the mean aortic pressure (i.e., resting distal renal artery pressure-to-aortic pressure ratio <0.90) is proposed as the threshold for hemodynamically significant renal FMD for angioplasty [72].

In ARAS, based on expert consensus, angiographic stenosis diameter >70% is considered severe or significant, and a stenosis diameter of 50–70% is considered moderate. For moderate-to-severe stenosis, confirmation of the hemodynamic severity of RAS is recommended prior to stenting [10]. The translesional pressure gradient should be measured using a nonobstructive catheter or a 0.014-inch pressure wire. A resting or hyperemic translesional systolic gradient ≥20 mmHg, a resting or hyperemic mean translesional gradient ≥10 mmHg, or a renal fractional flow reserve (RFFR) ≤0.8 can confirm hemodynamically severe RAS [10]. Hyperemia may be induced with an intrarenal bolus of papaverine or dopamine [17]. In post hoc analyses, the mean hyperemic gradient, hyperemic systolic gradient, and RFFR have been reported to be able to discriminate responders from nonresponders [73].

In general, the first-line revascularization technique in FMD-related RAS is PTRA without stenting, and in ARAS, it is PTRA with stenting. In both FMD and ARAS, translesional pressure gradient measurement should be performed postangioplasty to confirm that the pressure gradient has disappeared.

Atheroembolism typically occurs during manipulation of the catheter while selecting and engaging the renal artery or while advancing the stent across the stenosis. As a preventive measure, embolic protection devices can be used to prevent embolization during the placement of stents in the renal artery. Several observational studies report recovery of embolic debris and renal function stabilization after PTRA [56]; however, its clinical value is under debate and has not been established.

Follow-up after PTRA/restenosis

The initial clinical response to PTRA should be evaluated within 1–2 weeks after the procedure. Antihypertensive medications should be reassessed at follow-up visits, and screening for restenosis should be considered in the setting of unexplained BP increase and/or decline in renal function. In FMD, following renal angioplasty, prescription of 75–100 mg aspirin daily is recommended indefinitely, though some operators empirically prescribe a short course of dual antiplatelet therapy (e.g., 4–6 weeks) [72]. In ARAS, dual therapy, such as aspirin and clopidogrel, seems to be the standard treatment after stenting and is commonly administered for 4–6 weeks; however, dosing strategies for antiplatelet agents vary widely, and there are no prospective data on the comparative effectiveness of antiplatelet regimens after PTRA.

Restenosis and/or in-stent stenosis is one of the major complications that can occur at any time after renal PTRA, and accumulating experience shows that even angioplasty with stenting was hampered by a high rate of restenosis [74]. The precise frequency of restenosis after angioplasty remains unclear and probably varies among institutions. Larger diameter target vessels with a larger acute gain (poststent minimum lumen diameter) are reported to yield a lower restenosis rate than smaller diameter vessels with smaller acute gain [75]. The frequency of restenosis after PTRA was investigated in 175 RVH patients (FMD 30.3%), and the rates of restenosis within a year and within 5 years were found to be 20% and 32%, respectively, with a much higher rate in FMD than in ARAS [76].

In both FMD and ARAS, to detect findings suggestive of restenosis, surveillance with renal artery duplex ultrasound may include a study at the first office visit postangioplasty (usually within 1 month) [72, 74]. In FMD, duplex imaging is recommended every 6 months for 24 months and then yearly [72].

It is necessary to adjust the velocity parameters for a stented artery compared with a native vessel, as decreased compliance due to the stent will result in higher velocity [58]. In-stent stenosis of >70% can be confirmed by PSV >395 cm/s [77]. If duplex imaging is inconclusive, CTA would be the next best test for determining stent patency. If ultrasound and CTA are still inconclusive and the patient has recurrent clinical symptoms, angiography with hemodynamic confirmation of the severity of in-stent restenosis is indicated.

Conclusions

Physicians should recognize that restoring renal blood flow is effective and critical for specific RAS patients. Current clinical guidelines indicate that reasonable candidates for PTRA are patients with hemodynamically significant RAS with FMD with hypertension, refractory hypertension, rapid decline in renal function, or cardiac destabilization syndromes. As a practical matter, decisions for managing RAS patients must be highly individualized. When high BP, reduced eGFR, or high vascular risk is present, it seems prudent to examine the renal hemodynamics and anatomy to diagnose the presence or absence of RAS, its severity, whether bilateral or unilateral, and the relative size and functional characteristics of the kidney (Fig. 1). In some cases, the decision on therapeutic strategy remains difficult, but clinicians must evaluate individual patients carefully to determine the relative merits of relying on medical therapy or adding PTRA. Further, it is essential to consider ARAS as one aspect of atherosclerotic disease, which commonly progresses over a longer period of time, and some individuals with other comorbidities develop further manifestations of high-grade stenosis and high-risk features. Antihypertensive drug therapy should be managed to achieve goal BP, which is undertaken as part of the decision as to whether further consideration needs to be given to diagnostic and interventional procedures for RVH. Further investigation is required to identify RAS patients who demonstrably benefit from and respond to PTRA.

References

Herrmann SM, Textor SC. Current concepts in the treatment of renovascular hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31:139–49.

Rocha-Singh K, Jaff MR, Rosenfield K, Aspire-Trial Investigators. Evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of renal artery stenting after unsuccessful balloon angioplasty: the ASPIRE-2 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:776–83.

Weinberg I, Keyes MJ, Giri J, Rogers KR, Olin JW, White CJ, et al. Blood pressure response to renal artery stenting in 901 patients from five prospective multicenter FDA-approved trials. Catheter Cardiovasc Inter. 2014;83:603–9.

Jaff MR, Bates M, Sullivan T, Popma J, Gao X, Zaugg M, et al. Significant reduction in systolic blood pressure following renal artery stenting in patients with uncontrolled hypertension: results from the Hercules trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Inter. 2012;80:343–50.

Astral Investigators, Wheatley K, Ives N, Gray R, Kalra PA, Moss JG, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N. Engl J Med. 2009;361:1953–62.

Bax L, Woittiez AJ, Kouwenberg HJ, Mali WP, Buskens E, Beek FJ, et al. Stent placement in patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and impaired renal function: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:840–8.

Cooper CJ, Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, Jamerson K, Henrich W, Reid DM, et al. Stenting and medical therapy for atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis. N. Engl J Med. 2014;370:13–22.

Raman G, Adam GP, Halladay CW, Langberg VN, Azodo IA, Balk EM. Comparative effectiveness of management strategies for renal artery stenosis: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:635–49.

Balk EM, Raman G, Adam GP, Halladay CW, Langberg VN, Azodo IA, et al. Renal Artery Stenosis Management Strategies: An Updated Comparative Effectiveness Review. Report No.: 16-EHC026-EF. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016.

Klein AJ, Jaff MR, Gray BH, Aronow HD, Bersin RM, Diaz-Sandoval LJ, et al. SCAI appropriate use criteria for peripheral arterial interventions: an update. Catheter Cardiovasc Inter. 2017;90:E90–110.

Aboyans V, Ricco JB, Bartelink MEL, Bjorck M, Brodmann M, Cohnert T, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries. Endorsed by: the European Stroke Organization (ESO), the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:763–816.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13–15.

Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, Asayama K, Dohi Y, Hirooka Y, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1235–481.

Zeller T, Krankenberg H, Erglis A, Blessing E, Fuss T, Scheinert D, et al. A randomized, multi-center, prospective study comparing best medical treatment versus best medical treatment plus renal artery stenting in patients with hemodynamically relevant atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis (RADAR) - one-year results of a pre-maturely terminated study. Trials. 2017;18:380.

White CJ. The “chicken little” of renal stent trials: the CORAL trial in perspective. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:111–3.

Jenks S, Yeoh SE, Conway BR. Balloon angioplasty, with and without stenting, versus medical therapy for hypertensive patients with renal artery stenosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD002944.

Prince M, Tafur JD, White CJ. When and how should we revascularize patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:505–17.

Mishima E, Suzuki T, Ito S. Selection of patients for angioplasty for treatment of atherosclerotic renovascular disease: predicting responsive patients. Am J Hypertens. 2020;33:391–401.

Chrysant SG. The current status of angioplasty of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis for the treatment of hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2013;15:694–8.

Plouin PF, Chatellier G, Darne B, Raynaud A. Blood pressure outcome of angioplasty in atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: a randomized trial. Essai multicentrique medicaments vs angioplastie (EMMA) study group. Hypertension. 1998;31:823–9.

Mangiacapra F, Trana C, Sarno G, Davidavicius G, Protasiewicz M, Muller O, et al. Translesional pressure gradients to predict blood pressure response after renal artery stenting in patients with renovascular hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:537–42.

Adel SM, Syeidian SM, Najafi M, Nourizadeh M. Clinical efficacy of percutaneous renal revascularization with stent placement in hypertension among patients with atherosclerotic renovascular diseases. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2011;2:36–43.

Protasiewicz M, Kadziela J, Poczatek K, Poreba R, Podgorski M, Derkacz A, et al. Renal artery stenosis in patients with resistant hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:1417–20.

Kadziela J, Januszewicz A, Prejbisz A, Michalowska I, Januszewicz M, Florczak E, et al. Prognostic value of renal fractional flow reserve in blood pressure response after renal artery stenting (PREFER study). Cardiol J. 2013;20:418–22.

Jujo K, Saito K, Ishida I, Furuki Y, Ouchi T, Kim A, et al. Efficacy of 24-hour blood pressure monitoring in evaluating response to percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty. Circ J. 2016;80:1922–30.

Iwashima Y, Fukuda T, Kusunoki H, Hayashi SI, Kishida M, Yoshihara F, et al. Effects of percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty on office and home blood pressure and home blood pressure variability in hypertensive patients with renal artery stenosis. Hypertension. 2017;69:109–17.

Courand PY, Dinic M, Lorthioir A, Bobrie G, Grataloup C, Denarie N, et al. Resistant hypertension and atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: effects of angioplasty on ambulatory blood pressure. A retrospective uncontrolled single-center study. Hypertension. 2019;74:1516–23.

Ziakka S, Ursu M, Poulikakos D, Papadopoulos C, Karakasis F, Kaperonis N, et al. Predictive factors and therapeutic approach of renovascular disease: four years’ follow-up. Ren Fail. 2008;30:965–70.

Marcantoni C, Zanoli L, Rastelli S, Tripepi G, Matalone M, Mangiafico S, et al. Effect of renal artery stenting on left ventricular mass: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:39–46.

Leertouwer TC, Gussenhoven EJ, Bosch JL, van Jaarsveld BC, van Dijk LC, Deinum J, et al. Stent placement for renal arterial stenosis: where do we stand? A meta-analysis. Radiology. 2000;216:78–85.

Hanzel G, Balon H, Wong O, Soffer D, Lee DT, Safian RD. Prospective evaluation of aggressive medical therapy for atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, with renal artery stenting reserved for previously injured heart, brain, or kidney. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:1322–7.

Arthurs Z, Starnes B, Cuadrado D, Sohn V, Cushner H, Andersen C. Renal artery stenting slows the rate of renal function decline. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:726–31.

Dichtel LE, Gurevich D, Rifkin B, Varma P, Concato J, Peixoto AJ. Renal artery revascularization in patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and impaired renal function: conservative management versus renal artery stenting. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74:113–22.

Kane GC, Xu N, Mistrik E, Roubicek T, Stanson AW, Garovic VD. Renal artery revascularization improves heart failure control in patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2010;25:813–20.

Korsakas S, Mohaupt MG, Dinkel HP, Mahler F, Do DD, Voegele J, et al. Delay of dialysis in end-stage renal failure: prospective study on percutaneous renal artery interventions. Kidney Int. 2004;65:251–8.

Thatipelli M, Misra S, Johnson CM, Andrews JC, Stanson AW, Bjarnason H, et al. Renal artery stent placement for restoration of renal function in hemodialysis recipients with renal artery stenosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:1563–8.

Kashyap VS, Sepulveda RN, Bena JF, Nally JV, Poggio ED, Greenberg RK, et al. The management of renal artery atherosclerosis for renal salvage: does stenting help? J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:101–8.

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1–150.

Iwashima Y, Fukuda T, Horio T, Hayashi SI, Kusunoki H, Kishida M, et al. Association between renal function and outcomes after percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty in hypertensive patients with renal artery stenosis. J Hypertens. 2018;36:126–35.

Riaz IB, Husnain M, Riaz H, Asawaeer M, Bilal J, Pandit A, et al. Meta-analysis of revascularization versus medical therapy for atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:1116–23.

van Jaarsveld BC, Krijnen P, Pieterman H, Derkx FH, Deinum J, Postma CT, et al. The effect of balloon angioplasty on hypertension in atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis. Dutch Renal Artery Stenosis Intervention Cooperative Study Group. N. Engl J Med. 2000;342:1007–14.

Ritchie J, Green D, Chrysochou C, Chalmers N, Foley RN, Kalra PA. High-risk clinical presentations in atherosclerotic renovascular disease: prognosis and response to renal artery revascularization. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:186–97.

Khosla S, White CJ, Collins TJ, Jenkins JS, Shaw D, Ramee SR. Effects of renal artery stent implantation in patients with renovascular hypertension presenting with unstable angina or congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:363–6.

Gray BH, Olin JW, Childs MB, Sullivan TM, Bacharach JM. Clinical benefit of renal artery angioplasty with stenting for the control of recurrent and refractory congestive heart failure. Vasc Med. 2002;7:275–9.

Cuspidi C, Dell’Oro R, Sala C, Tadic M, Gherbesi E, Grassi G, et al. Renal artery stenosis and left ventricular hypertrophy: an updated review and meta-analysis of echocardiographic studies. J Hypertens. 2017;35:2339–45.

Devereux RB, Wachtell K, Gerdts E, Boman K, Nieminen MS, Papademetriou V, et al. Prognostic significance of left ventricular mass change during treatment of hypertension. JAMA. 2004;292:2350–6.

Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, Gattobigio R, Zampi I, et al. Prognostic significance of serial changes in left ventricular mass in essential hypertension. Circulation. 1998;97:48–54.

Iwashima Y, Fukuda T, Horio T, Kusunoki H, Hayashi SI, Kamide K, et al. Impact of percutaneous revascularization on left ventricular mass and its relationship to outcome in hypertensive patients with renal artery stenosis. Am J Hypertens. 2020;33:570–80.

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36:1953–2041.

Zeller T, Frank U, Muller C, Burgelin K, Sinn L, Bestehorn HP, et al. Predictors of improved renal function after percutaneous stent-supported angioplasty of severe atherosclerotic ostial renal artery stenosis. Circulation. 2003;108:2244–9.

Muray S, Martin M, Amoedo ML, Garcia C, Jornet AR, Vera M, et al. Rapid decline in renal function reflects reversibility and predicts the outcome after angioplasty in renal artery stenosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:60–6.

Vassallo D, Ritchie J, Green D, Chrysochou C, Kalra PA. The effect of revascularization in patients with anatomically significant atherosclerotic renovascular disease presenting with high-risk clinical features. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2018;33:497–506.

Kim S, Kim MJ, Jeon J, Jang HR, Park KB, Huh W, et al. Effects of percutaneous angioplasty on kidney function and blood pressure in patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2019;38:336–46.

Kennedy DJ, Colyer WR, Brewster PS, Ankenbrandt M, Burket MW, Nemeth AS, et al. Renal insufficiency as a predictor of adverse events and mortality after renal artery stent placement. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:926–35.

Zeller T, Muller C, Frank U, Burgelin K, Schwarzwalder U, Horn B, et al. Survival after stenting of severe atherosclerotic ostial renal artery stenoses. J Endovasc Ther. 2003;10:539–45.

Textor SC, Misra S, Oderich GS. Percutaneous revascularization for ischemic nephropathy: the past, present, and future. Kidney Int. 2013;83:28–40.

Murphy TP, Cooper CJ, Pencina KM, D’Agostino R, Massaro J, Cutlip DE, et al. Relationship of albuminuria and renal artery stent outcomes: results from the CORAL randomized clinical trial (Cardiovascular Outcomes with Renal Artery Lesions). Hypertension. 2016;68:1145–52.

Chi YW, White CJ, Thornton S, Milani RV. Ultrasound velocity criteria for renal in-stent restenosis. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:119–23.

Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Bbiology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; Transatlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation. 2006;113:e463–654.

Chrysochou C, Green D, Ritchie J, Buckley DL, Kalra PA. Kidney volume to GFR ratio predicts functional improvement after revascularization in atheromatous renal artery stenosis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0177178.

Doi Y, Iwashima Y, Yoshihara F, Kamide K, Takata H, Fujii T, et al. Association of renal resistive index with target organ damage in essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:1292–8.

Doi Y, Iwashima Y, Yoshihara F, Kamide K, Hayashi S, Kubota Y, et al. Renal resistive index and cardiovascular and renal outcomes in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2012;60:770–7.

Radermacher J, Chavan A, Bleck J, Vitzthum A, Stoess B, Gebel MJ, et al. Use of Doppler ultrasonography to predict the outcome of therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N. Engl J Med. 2001;344:410–7.

Bruno RM, Daghini E, Versari D, Sgro M, Sanna M, Venturini L, et al. Predictive role of renal resistive index for clinical outcome after revascularization in hypertensive patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: a monocentric observational study. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2014;12:9.

Matayoshi T, Kamide K, Tanaka R, Fukuda T, Horio T, Iwashima Y, et al. Factors associated with outcomes of percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty in patients with renal artery stenosis: a retrospective analysis of 50 consecutive cases. Int J Hypertens 2018;2018:1952685.

Garcia-Criado A, Gilabert R, Nicolau C, Real MI, Muntana X, Blasco J, et al. Value of Doppler sonography for predicting clinical outcome after renal artery revascularization in atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:1641–7.

Crutchley TA, Pearce JD, Craven TE, Stafford JM, Edwards MS, Hansen KJ. Clinical utility of the resistive index in atherosclerotic renovascular disease. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:148–55.

Trinquart L, Mounier-Vehier C, Sapoval M, Gagnon N, Plouin PF. Efficacy of revascularization for renal artery stenosis caused by fibromuscular dysplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2010;56:525–32.

De Bruyne B, Manoharan G, Pijls NH, Verhamme K, Madaric J, Bartunek J, et al. Assessment of renal artery stenosis severity by pressure gradient measurements. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1851–5.

Drieghe B, Madaric J, Sarno G, Manoharan G, Bartunek J, Heyndrickx GR, et al. Assessment of renal artery stenosis: side-by-side comparison of angiography and duplex ultrasound with pressure gradient measurements. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:517–24.

Olin JW, Gornik HL, Bacharach JM, Biller J, Fine LJ, Gray BH, et al. Fibromuscular dysplasia: state of the science and critical unanswered questions: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:1048–78.

Gornik HL, Persu A, Adlam D, Aparicio LS, Azizi M, Boulanger M, et al. First international consensus on the diagnosis and management of fibromuscular dysplasia. J Hypertens. 2019;37:229–52.

van Brussel PM, van de Hoef TP, de Winter RJ, Vogt L, van den Born BJ. Hemodynamic measurements for the selection of patients with renal artery stenosis: a systematic review. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:973–85.

Boateng FK, Greco BA. Renal artery stenosis: prevalence of, risk factors for, and management of in-stent stenosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61:147–60.

Lederman RJ, Mendelsohn FO, Santos R, Phillips HR, Stack RS, Crowley JJ. Primary renal artery stenting: characteristics and outcomes after 363 procedures. Am Heart J. 2001;142:314–23.

Iwashima Y, Fukuda T, Yoshihara F, Kusunoki H, Kishida M, Hayashi S, et al. Incidence and risk factors for restenosis, and its impact on blood pressure control after percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty in hypertensive patients with renal artery stenosis. J Hypertens. 2016;34:1407–15.

Granata A, Fiorini F, Andrulli S, Logias F, Gallieni M, Romano G, et al. Doppler ultrasound and renal artery stenosis: an overview. J Ultrasound. 2009;12:133–43.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C), Number 17K09743.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Iwashima, Y., Ishimitsu, T. How should we define appropriate patients for percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty treatment?. Hypertens Res 43, 1015–1027 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0496-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0496-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension 2025 (JSH2025)

Hypertension Research (2026)

-

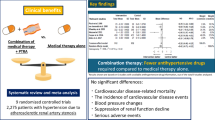

Combination of medical therapy and percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty versus medical therapy alone for patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: systematic review and meta-analysis

Hypertension Research (2025)