Abstract

Smoking predisposes individuals to endothelial dysfunction. Flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and reactive hyperemia peripheral artery tonometry (RH-PAT) are used to assess endothelial function. However, whether smoking cessation demonstrates comparable effects on endothelial function evaluated by FMD and RH-PAT remains unclear. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the effects of smoking cessation on endothelial function evaluated simultaneously by FMD and RH-PAT and clarify the factors associated with these effects. Fifty-eight consecutive current smokers (mean ± standard deviation; age, 64 ± 11 years) who visited our smoking cessation outpatient department and succeeded with smoking cessation were enrolled. Twenty-one continued smokers were enrolled as age- and sex-matched controls. Clinical variables, FMD, and natural logarithmic transformation of the reactive hyperemia index (Ln-RHI) were examined before and 20 weeks after treatment initiation. In 58 smokers who succeeded with smoking cessation, FMD significantly improved (3.80 ± 2.24 to 4.60 ± 2.55%; p = 0.013), whereas Ln-RHI did not (0.59 ± 0.28 to 0.66 ± 0.22; p = 0.092). Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between changes in FMD and Ln-RHI was −0.004, and the intraclass correlation coefficient for a two-way mixed effects model was <0.001 (p = 0.499). In multivariate analysis, the presence of an increase in FMD was inversely correlated with the Brinkman index and changes in systolic blood pressure (SBP), whereas Ln-RHI was positively correlated with changes in SBP and inversely correlated with baseline body mass index. These factors may predict the varying effects of smoking cessation on the endothelial function of the conduit and digital vessels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

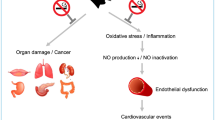

Smoking predisposes individuals to endothelial dysfunction and eventually arteriosclerosis and is regarded as a major risk factor for the development of cardiovascular diseases [1]. Therefore, smoking cessation remains the most crucial intervention in preventive and preemptive medicine [2].

Flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and reactive hyperemia peripheral artery tonometry (RH-PAT) are used to assess endothelial function [3,4,5]. FMD is mainly measured using the brachial artery, and RH-PAT is measured by recording the finger arterial pulse wave amplitude (PWA) and calculating the reactive hyperemia index (RHI). There are differences between these two methods in the physiology of vascular beds being tested and in the response of the conduit and resistive vessels to RH [3, 6].

Smoking intensity is independently associated with endothelial function evaluated by measuring FMD, and FMD improves after smoking cessation [2, 7]. Current smoking has been shown to be associated with abnormal RHI, and RHI improves after smoking cessation [4, 8]. However, it is unclear whether smoking cessation has a comparable effect on endothelial function assessed by FMD and by RHI [3, 9]. Thus, the present study aimed to evaluate the effects of smoking cessation on endothelial function assessed simultaneously by FMD and RH-PAT and clarify the factors associated with these effects.

Methods

Study population

Fifty-eight consecutive current smokers (mean ± standard deviation [SD]; age, 64 ± 11 years) who visited our smoking cessation outpatient department from June 2013 to December 2018 and succeeded with smoking cessation 20 weeks after the initiation of the smoking cessation program were enrolled in this study (abstainers). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age ≥ 20 years, (2) Brinkman index (number of cigarettes per day × years of smoking) ≥ 200, (3) nicotine-dependence score ≥ 5 (the Tobacco Dependence Screener, TDS), and (4) motivation to quit smoking. All 58 patients fulfilled the criteria and were enrolled in the present study. The criteria complied with the Japanese drug use system for nicotine-dependent outpatients. Pharmacotherapies including varenicline (partial agonist of alpha-4 beta-2 nicotinic receptors) or nicotine patches (nicotine transdermal therapeutic system; nicotine TTS) were used as smoking cessation aids when required. Twenty-one current smokers who visited our smoking cessation outpatient department but did not achieve smoking cessation were enrolled as age- and sex-matched controls (continued smokers).

The study protocols adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the ethics committee of Osaka City University (No. 1744, 1752). Written informed consent was obtained from all 79 patients.

Study protocol

FMD and RH-PAT were simultaneously performed in all enrolled patients at baseline before smoking cessation. When needed for smoking cessation, pharmacotherapies such as varenicline or nicotine patches were administered after the vascular tests and venous blood collection at baseline. Varenicline was titrated up to 1.0 mg twice daily as follows: 0.5 mg once daily for 3 days, then 0.5 mg twice daily for 4 days, and then 1.0 mg twice daily for 11 weeks. Varenicline was discontinued at the 12th week. For nicotine patches, 30-cm2 nicotine TTS was applied once daily for 4 weeks; then, 20-cm2 nicotine TTS was applied once daily for 2 weeks, followed by 10-cm2 nicotine TTS once daily for 2 weeks. Nicotine patches were discontinued at the 8th week. All patients were advised to visit our smoking cessation clinic at the 2nd, 4th, 8th, 12th, and 20th weeks. Self-reported smoking status, adverse event information, body weight, and exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) concentration were assessed at each visit. Smoking cessation was confirmed by self-reported smoking status and an exhaled CO level <4 ppm at the 20th week [10, 11]. Venous blood collection and vascular tests, including FMD and RH-PAT, were reperformed at the 20th week. We set the effect determination timing to the 20th week to assess the effect of smoking cessation itself rather than the effect of pharmacotherapies. Smokers who stopped smoking by the 12th week but resumed smoking by the 20th week were not enrolled as smokers who succeeded with smoking cessation in this study. None of the drug regimens were changed during the study period.

Measurement of FMD

FMD was examined at baseline and at the 20th week. FMD measurements were performed according to the guidelines for FMD assessment [12]. All participants were required to fast for at least 12 h; avoid heavy exercise for at least 24 h; not consume caffeine-containing products, alcohol, or antioxidant vitamins for at least 6 h; withhold all drugs for at least 12 h; and sleep soundly for at least 6 h the night before the measurement. Among premenopausal women, the examinations were performed during the menstrual period. All participants rested in the sitting position in a quiet, dimmed, and temperature-controlled room (22–25 °C) for 15 min and then were placed in the supine position for 15 min. Measurement of the right brachial artery was performed between 7:00 a.m. and 11:59 a.m.

We used a 10-MHz H-type probe (UNEXEF; UNEX, Nagoya, Japan) equipped with semiautomatic vessel wall tracking software and provided one longitudinal, two short-axis B-mode images, and one processed A-mode lines-image of the right brachial artery, as previously described [13]. Each B-mode vessel image was detected and tracked automatically from the two short-axis images to select the most likely position of the brachial artery and to maintain positional stability of the A-mode lines. Measurements of the vessel lumen on the longitudinal image were automatically performed using the A-mode lines. A total of 20 bilateral points in a designated position on a total of 41 A-mode lines were measured every 0.15 mm. The measured values were averaged and shown on the image. A B-mode edge detection method was designed to automatically maintain the same position of the right brachial artery by adjusting the deviation of the probe position before and after compression at the right forearm to achieve a precise measurement of the vessel lumen. Electrocardiogram gating was used during image acquisition, where the onset of the R-wave was used to identify the end-diastole. After determining the probe position where the clear baseline image was obtained, the forearm cuff was inflated up to at least 50 mmHg above the systolic blood pressure (SBP) for 5 min. Longitudinal images of the right brachial artery were continuously recorded from 0 s after cuff inflation to 5 min after cuff release. The percentage of maximum change from the resting baseline lumen diameter to that of the hyperemic state divided by the baseline lumen diameter was defined as the FMD. Pulsed Doppler flow was assessed at baseline and during peak hyperemic flow, and blood flow velocity was calculated from the color Doppler data. Blood flow volume was calculated by multiplying the Doppler flow velocity by the heart rate and cross-sectional vessel area. Reactive hyperemia was calculated as the maximum percentage increase in flow after cuff deflation compared with the baseline flow.

Measurement of RH-PAT

RH‑PAT measurements were performed using an Endo‑PAT 2000 (Itamar Medical Ltd, Caesarea, Israel) concurrently with FMD of a single forearm occlusion, and the measurements were automatically analyzed to obtain the RHI using EndoPAT™ software, version 3.5.4 (Itamar Medical). Before the examinations, patients remained in the supine position for 15 min. PAT sensors were placed on the index fingers of the right and left hands. The right arm was tested, while the left served as a control. Each measurement consisted of 5 min of basal recording, 5 min of right brachial artery occlusion, and 5 min of reactive hyperemia measurement. The forearm cuff was inflated up to at least 50 mmHg above the SBP for 5 min. The pulse amplitude was recorded electronically throughout the study, and the data were analyzed in a blinded fashion using a computerized and semiautomated algorithm. The 15-min recordings were then analyzed using the device’s proprietary software, and the RHI was calculated by the device using the method previously described by McCrea [14]. We used the natural logarithmic transformation of the RHI (Ln-RHI) [4].

Clinical data and definitions

Laboratory data were obtained from fasting blood samples taken under the same conditions on the same day as the FMD and RH-PAT measurements. The medical records of each of the 79 patients were comprehensively reviewed. Among the variables used in the analyses, hypertension was defined as SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic BP (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg, and/or antihypertensive medication use. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl, glycated hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%, and/or current insulin or oral hypoglycemic agent use. Dyslipidemia was defined as high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) < 40 mg/dl, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) ≥ 140 mg/dl, non-HDL cholesterol ≥ 170 mg/dl, triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dl, and/or lipid-lowering medication use.

In this study, FMD was considered to have increased if the FMD at the follow-up minus the FMD at baseline was more than 0. Ln-RHI was considered to have increased if the Ln-RHI at the follow-up minus the Ln-RHI at baseline was more than 0.

Statistical analysis

Clinical characteristics are presented as the means ± SDs for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables. Student’s unpaired t test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare baseline clinical variables between the smoking cessation and control groups. Student’s paired t test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare clinical variables at baseline and follow-up. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the clinical variables among the three types of therapy groups, and the categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. We calculated Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for a two-way mixed effects model to assess the agreement between changes in FMD and Ln-RHI. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the associations between the presence of an increase in FMD or Ln-RHI and each clinical variable adjusted for age and sex. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (Version 20.0, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois) and R version 3.4.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). P values < 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

We enrolled 58 consecutive current smokers (mean ± SD; age, 64 ± 11 years) who visited our smoking cessation outpatient department and succeeded with smoking cessation; the patients were evaluated for endothelial function by FMD and RH-PAT at baseline and at the 20th week after the initiation of the smoking cessation program. We enrolled 21 continued smokers (mean ± SD; age, 61 ± 8 years) to form an age- and sex-matched control group. The baseline characteristics of the abstainers and continued smokers are listed in Table 1. No significant differences were found between the two groups, except in DBP. As smoking cessation aids, 38 abstainers, and 9 continued smokers used varenicline, while 12 abstainers and 6 continued smokers used nicotine patches. No cardiovascular events or significant side effects of varenicline or nicotine patches were documented during the study period. There were three premenopausal women among the abstainers, and no premenopausal women among the continued smokers. The three premenopausal women were examined during their menstrual period.

Changes in clinical parameters

Clinical parameters at baseline and the follow-up period of the abstainers are shown in Table 2. After smoking cessation, CO was significantly decreased (10.4 ± 7.8 to 2.0 ± 0.8 ppm; p < 0.001). There were significant increases in body mass index (BMI) (23.6 ± 4.0 to 24.3 ± 4.1 kg/m2; p < 0.001), waist circumference (85.8 ± 11.0 to 87.8 ± 11.7 cm; p = 0.002), SBP (118.6 ± 20.7 to 124.8 ± 18.8 mmHg; p < 0.001), DBP (74.4 ± 11.0 to 77.1 ± 10.9 mmHg; p = 0.009), homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (1.73 ± 1.33 to 2.04 ± 1.79; p = 0.016), total cholesterol (190.7 ± 37.7 to 195.8 ± 37.7 mg/dl; p = 0.025), and HDL-C (51.9 ± 18.2 to 54.9 ± 19.8 mg/dl; p = 0.038), whereas there were no significant changes in heart rate, fasting glucose, LDL-C, triglycerides, C-reactive protein, or cardio-ankle vascular index. Moreover, no significant changes were observed in the continued smokers (Table 3).

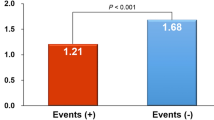

Evaluation of changes in FMD and Ln-RHI

In the abstainers, as shown in Table 2, there was significant improvement in endothelial function assessed by FMD (3.80 ± 2.24 to 4.60 ± 2.55%; p = 0.013), whereas there were no significant changes in endothelial function assessed by RH-PAT (Ln-RHI) (0.59 ± 0.28 to 0.66 ± 0.22; p = 0.092). The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between the changes in FMD and Ln-RHI was −0.004 (Fig. 1), and the ICC was <0.001 (p = 0.499). In addition, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient and ICC were −0.013 and −0.002 (p = 0.506), respectively, in abstainers treated with varenicline; −0.049 and 0.004 (p = 0.506), respectively, in abstainers treated with nicotine patches; and −0.107 and 0.012 (p = 0.489), respectively, in abstainers treated with no pharmacotherapies.

Changes in endothelial function assessed by flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and reactive hyperemia peripheral artery tonometry (RH-PAT) in abstainers (n = 58). Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between the changes in FMD and a natural logarithmic transformation of the RH index (Ln-RHI) is −0.004 (p = 0.977)

Predictors of increase in FMD or Ln-RHI

Among the abstainers, 62.1% (36/58) presented an increase in FMD, 60.3% (35/58) presented an increase in Ln-RHI, and 34.5% (20/58) presented an increase in both FMD and Ln-RHI during the follow-up period (Table 4). The prevalence of an increase in FMD or Ln-RHI was not significantly different among the three therapy groups. In the logistic regression analysis, which was adjusted for age and sex (Table 5), an increase in FMD was predicted on the basis of the Brinkman index (odds ratio = 0.99, p = 0.043), baseline FMD (odds ratio = 0.73, p = 0.030) and changes in SBP (odds ratio = 0.94, p = 0.040). An increase in Ln-RHI was predicted on the basis of baseline BMI (odds ratio = 0.83, p = 0.032), baseline Ln-RHI (odds ratio = 0.01, p = 0.001), and changes in SBP (odds ratio = 1.06, p = 0.047).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated significant improvement in endothelial function assessed by FMD, but not by RH-PAT, after smoking cessation. In addition, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient and the ICC did not show an agreement of changes between FMD and Ln-RHI. The presence of an increase in FMD and Ln-RHI was differently associated with the clinical variables. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess endothelial function by FMD and RH-PAT simultaneously before and after smoking cessation and demonstrate different serial changes in endothelial function between FMD and RH-PAT assessments.

In a large, community-based cohort, RHI was not significantly correlated with FMD [15]. This study suggested that physiological differences due to vessel sizes underlie divergent brachial and digital reactivity and that FMD and RH-PAT provide distinct information regarding vascular function [15].

FMD is particularly sensitive to being impaired by risk factors such as age and hypertension, whereas the RHI is more sensitive to metabolic risk factors such as BMI and diabetes [3, 4, 15]. In our study, smoking cessation led to a significant increase in BMI, as previously reported [7]. The presence of an increase in Ln-RHI was inversely correlated with the baseline BMI. The lower digital hyperemic response in obese participants is consistent with impaired microvessel flow reserve, which may contribute to impaired blood flow supply in the setting of increased metabolic demands [4]. These results may indicate that smokers who have a higher baseline BMI may be prone to a decrease in Ln-RHI after smoking cessation, which is often accompanied by an increase in BMI.

In our study, BP increased after smoking cessation, and the presence of an increase in FMD was inversely correlated with the change in SBP. In contrast, Ln-RHI was positively correlated with the change in SBP. Some previous studies have indicated that smoking cessation might result in an increase in BP. However, other studies have not confirmed this finding [16, 17]. It should be considered that smoking cessation influences other factors, including total food intake, weight gain, alcohol intake, and other health-related behaviors that can affect BP [16]. Although these factors were not thoroughly evaluated in the current study, smoking cessation itself resulted in an increased BP in our population. In previous literature, a higher SBP was associated with a higher prevalence of abnormal FMD and a lower prevalence of abnormal RHI [15, 18]. It was speculated that an elevated BP might lead to increased microvascular compliance due to changes in tones or structure that, in turn, produce higher hyperemic pulse amplitude in the digits [15]. Therefore, the differential effects of changes in SBP may, in part, contribute to the disagreement between the changes in FMD and Ln-RHI after smoking cessation.

In our study, decreased endothelial function was likely to improve, and less-severely decreased endothelial function was less likely to improve after smoking cessation. These results indicate that endothelial dysfunction resulting from smoking exposure may be more easily restored by smoking cessation even if the endothelial dysfunction is severe. Previous studies also suggested that cigarette smoking was associated with a potentially reversible impairment of endothelial function in healthy young adults and that smoking cessation improved coronary endothelial function in patients with recent myocardial infarction [19, 20]. Although the precise mechanisms are undetermined, cigarette smoke exposure increases oxidative stress, which is a potential mechanism for initiating cardiovascular dysfunction, whereas smoking cessation reduces oxidative damage to endothelial cells, increases nitric oxide availability, and increases the mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells from the bone marrow [7, 21]. These peculiarities of endothelial damage associated with smoking exposure may partially account for the results obtained in the logistic regression analysis in this study.

In this study, there were three therapy groups: the varenicline, nicotine patch, or no pharmacotherapy groups. Although the number in each group was small, agreement between changes in FMD and Ln-RHI after smoking cessation was not found in each therapy group. In abstainers treated with varenicline, decreased endothelial function was likely to improve, and less-severely decreased endothelial function was less likely to improve after smoking cessation. Similar tendencies were found in abstainers treated with nicotine patches and those who received no pharmacotherapies, although these findings were not statistically significant. We speculate that if the numbers in each group were sufficient, no significant differences would be found among the three groups in terms of the relationship between baseline FMD or Ln-RHI and the degree of improvement in vascular endothelial function. As we set the effect determination timing as the 20th week, which was 8 weeks after the 12 weeks of the smoking cessation program, we suspect that the differences among the three types of therapies might have been minimized or almost canceled out and that improvement in endothelial function might have been mainly due to the effect of smoking cessation itself.

Previous studies reached conflicting conclusions regarding a dose-response relationship between cigarette smoking and cardiovascular risk [7, 19, 21]. Small doses of toxic components from cigarette smoke may have a nonlinear dose-response effect on vascular function [21]. It has been reported that smoking cessation can partially reverse this phenomenon [19]. In our study, the Brinkman index was not associated with the baseline FMD (data not shown). However, a higher Brinkman index was associated with a lower prevalence of an increase in FMD after smoking cessation. These findings may suggest a linear dose-response relationship of smoking with the reversibility of FMD after smoking cessation.

The present study has some limitations. First, although we enrolled consecutive subjects who visited the smoking cessation outpatient department and achieved smoking cessation or continued smoking, the number of subjects enrolled was too small to adjust for all the covariates of the FMD and Ln-RHI changes. Second, pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation in patients included not only varenicline but also nicotine replacement therapy or no pharmacotherapy. Further prospective studies including pharmacotherapy-matched groups are necessary to completely clarify the effects of smoking cessation on FMD and Ln-RHI. Third, proper palmar digital artery (PPDA) stenosis was reported to cause a decrease in the PWA and an underestimation of the RHI values [22]. We did not find any cases in which PPDA was strongly suspected due to the presence of decreased baseline PWA, decreased Ln-RHI, or a decrease in Ln-RHI after smoking cessation in this study. Hence, we suspect that PPDA stenosis might not be related to disagreements between the changes in FMD and Ln-RHI in our population. However, we did not evaluate PPDA stenosis in detail by angiography. Further examinations are warranted to clarify this issue.

In conclusion, we demonstrated significant improvement in endothelial function assessed by FMD, but not by RH-PAT, after smoking cessation. In addition, we demonstrated disagreements between the changes in FMD and Ln-RHI. Increases in FMD and Ln-RHI were differently correlated with clinical variables, including baseline BMI, SBP changes, and the Brinkman index. These factors may be able to predict the varying effects of smoking cessation on the endothelial function of the conduit and digital vessels.

References

Teo KK, Ounpuu S, Hawken S, Pandey MR, Valentin V, Hunt D, et al. Tobacco use and risk of myocardial infarction in 52 countries in the INTERHEART study: a case-control study. Lancet. 2006;368:647–58.

Kobayashi M, Takemoto Y, Norioka N, Iguchi T, Shimada K, Maeda M, et al. Vascular functional and morphological alterations in smokers during varenicline therapy. Osaka City Med J. 2015;61:19–30.

Flammer AJ, Anderson T, Celermajer DS, Creager MA, Deanfield J, Ganz P, et al. The assessment of endothelial function—from research into clinical practice. Circulation. 2012;126:753–67.

Hamburg NM, Keyes MJ, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Schnabel R, Pryde MM, et al. Cross-sectional relations of digital vascular function to cardiovascular risk factors in The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:2467–74.

Tomiyama H, Yoshida M, Higashi Y, Takase B, Furumoto T, Kario K, et al. Autonomic nervous activation triggered during induction of reactive hyperemia exerts a greater influence on the measured reactive hyperemia index by peripheral arterial tonometry than on flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery in patients with hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2014;37:914–8.

Allan RB, Delaney CL, Miller MD, Spark JI. A comparison of flow-mediated dilatation and peripheral artery tonometry for measurement of endothelial function in healthy individuals and patients with peripheral arterial disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;45:263–9.

Johnson HM, Gossett LK, Piper ME, Aechlimann SE, Korcarz CE, Baker TB, et al. Effects of smoking and smoking cessation on endothelial function: 1-year outcomes from a randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1988–95.

Xue C, Chen QZ, Bian L, Yin ZF, Xu ZJ, Zang AL, et al. Effects of smoking cessation with nicotine replacement therapy on vascular endothelial function, arterial stiffness, and inflammation response in healthy smokers. Angiology. 2019;70:719–25.

Lavi S, Prasad A, Yan EH, Mathew V, Simari RD, Rihal CS, et al. Smoking is associated with epicardial coronary endothelial dysfunction and elevated white blood cell count in patients with chest pain and early coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2007;115:2621–7.

Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, Jao NC. Optimal carbon monoxide criteria to confirm 24-hr smoking abstinence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:978–82.

Cropsey KL, Trent LR, Clark CB, Stevens EN, Lahti AC, Hendricks PS. How low should you go? Determining the optimal cutoff for exhaled carbon monoxide to confirm smoking abstinence when using cotinine as reference. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;16:1348–55.

Corretti MC, Anderson TJ, Benjamin EJ, Celermajer D, Charbonneau F, Creager MA, et al. Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: a report of the international brachial artery reactivity task force. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:257–65.

Iguchi T, Takemoto Y, Shimada K, Matsumoto K, Nakanishi K, Otsuka K, et al. Simultaneous assessment of endothelial function and morphology in the brachial artery using a new semiautomatic ultrasound system. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:691–7.

McCrea CE, Skulas-Ray AC, Chow M, West SG. Test-retest reliability of pulse amplitude tonometry measures of vascular endothelial function: Implications for clinical trial design. Vasc Med. 2012;17:29–36.

Hamburg NM, Palmisano J, Larson MG, Sullivan LM, Lehman BT, Vasan RS, et al. Relation of brachial and digital measures of vascular function in the community: the Framingham heart study. Hypertension. 2011;57:390–6.

Lee DH, Ha MH, Kim JR, Jacobs JrDR. Effects of smoking cessation on changes in blood pressure and incidence of hypertension: a 4-year follow-up study. Hypertension. 2001;37:194–8.

Greene SB, Aavedal MJ, Tyroler HA, Davis CE, Hames CG. Smoking habits and blood pressure change: a seven year follow up. J Chronic Dis. 1977;30:401–13.

Schnabel RB, Schulz A, Wild PS, Sinning CR, Wilde S, Eleftheriadis M, et al. Noninvasive vascular function measurement in the community cross-sectional relations and comparison of methods. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:371–80.

Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Georgakopoulos D, Bull C, Thomas O, Robinson J, et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with dose-related and potentially reversible impairment of endothelium-dependent dilation in healthy young adults. Circulation. 1993;88:2149–55.

Hosokawa S, Hiasa Y, Miyazaki S, Ogura R, Miyajima H, Ohara Y, et al. Effects of smoking cessation on coronary endothelial function in patients with recent myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2008;128:48–52.

Ambrose JA, Barua RS. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1731–7.

Kishimoto S, Matsumoto T, Maruhashi T, Iwamoto Y, Kajikawa M, Oda N, et al. Reactive hyperemia-peripheral arterial tonometry is useful for assessment of not only endothelial function but also stenosis of the digital artery. Int J Cardiol. 2018;260:178–83.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported, in part, by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan (15K08649, 19K07943). We thank Ryoichi Kita and Yukie Imai for their excellent technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fukumoto, K., Takemoto, Y., Norioka, N. et al. Predictors of the effects of smoking cessation on the endothelial function of conduit and digital vessels. Hypertens Res 44, 63–70 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0516-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0516-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effects of smoking cessation on endothelial function as assessed by flow-mediated total dilation

Cardiovascular Ultrasound (2024)

-

Smoking cessation and vascular endothelial function

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Current topic of vascular function in hypertension

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Comparison of the usefulness of the cardio-ankle vascular index and augmentation index as an index of arteriosclerosis in patients with essential hypertension

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

Which is the best method in clinical practice for assessing improvement in vascular endothelial function after successful smoking cessation — Flow-mediated dilation (FMD) or reactive hyperemic peripheral arterial tonometry (RH-PAT)?

Hypertension Research (2021)