Abstract

Despite the clinical usefulness of self-measured home blood pressure (BP), reports on the characteristics of home BP have not been sufficient and have varied due to the measurement conditions in each study. We constructed a database on self-measured home BP, which included five Japanese general populations as subdivided aggregate data that were clustered and meta-analyzed according to sex, age category, and antihypertensive drug treatment at baseline (treated and untreated). The self-measured home BPs were collected after a few minutes of rest in a sitting position: (1) the morning home BP was measured within 1 h of waking, after urination, before breakfast, and before taking antihypertensive medication (if any); and (2) the evening home BP was measured just before going to bed. The pulse rate was simultaneously measured. Eligible data from 2000 onward were obtained. The morning BP was significantly higher in treated participants than in untreated people of the same age category, and the BP difference was more marked in women. Among untreated residents, home systolic/diastolic BPs measured in the morning were higher than those measured in the evening; the differences were 5.7/5.0 mmHg in women (ranges across the cohorts, 5.3–6.8/4.7–5.4 mmHg) and 7.3/7.7 mmHg in men (ranges, 6.4–8.5/7.0–8.7 mmHg). In contrast, the home pulse rate in women and men was 2.4 (range, 1.5–3.7) and 5.6 (range, 4.6–6.6) beats per minute, respectively, higher in the evening than in the morning. We demonstrated the current status of home BP and home pulse rate in relation to sex, age, and antihypertensive treatment status in the Japanese general population. The approach by which fine-clustered aggregate statistics were collected and integrated could address practical issues raised in epidemiological research settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease [1], and the accumulation of other risk factors [2, 3] enhances the cardiovascular risk in patients with hypertension. The self-measurement of blood pressure at home by automated devices is useful for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension [4, 5] because a number of readings can be obtained over a long period, resulting in highly reproducible values without observer bias when patients apply a standardized protocol [1, 6, 7]. Home blood pressure measurement devices have become affordable and user-friendly [8], and the measurement values have greater prognostic ability for cardiovascular complications than those measured in conventional office blood pressure settings [9,10,11].

Although the generalizability of population-based findings is greater than those emerging from selected hypertensive patients, multicenter-based reports on home blood pressure among the general population have not been sufficient. The International Database of HOme blood pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcome (IDHOCO) [12] consists of five general population samples; however, the detailed conditions of home blood pressure measurement have varied among studies, e.g., evening measurement periods varied, with one measurement performed around dinner time (17:00–23:00) [13] and another performed just before the participant went to bed [14]. Furthermore, the blood pressure measurement devices in the IDHOCO differed in each cohort, and the catchment periods of home blood pressure were in the 1980s–1990s. Lifestyle modifications and the introduction of new antihypertensive drugs over the past decades have reduced conventional office blood pressure levels and have increased the hypertension treatment rate in the population [1, 15]. However, there are currently no nationwide collections of home blood pressure data in Japan, which produces more blood pressure monitoring devices than any other country in the world [16] and where it is estimated that 40 million home blood pressure devices are in use [17]. There is also a lack of data on home pulse rate measures, which can be self-measured by an automated device simultaneously with home blood pressure and has prognostic significance independent of blood pressure levels [18].

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the current status of self-measured blood pressure and the pulse rate in the Japanese general population since 2000 under well-defined conditions using the same types of home measurement devices.

Methods

Study design

The modern database on self-measured home blood pressure (MDAS) is a Japanese registry conducted to address recently raised issues associated with self-measured home blood pressure. The MDAS project was initiated in 2017, and studies performed in general populations were considered eligible if they met the following conditions: receipt of ethical approval from an institutional review board; enrolled participants gave their informed consent; and findings with home blood pressure data had been reported in peer-reviewed journals. The home blood pressure of the study participants should be self-measured on at least 5 days by a validated upper-arm cuff-oscillometric monitor. The studies should also follow a basic procedure proposed by the Japanese guidelines for home blood pressure measurement in 2003 [19], which was constructed based on the conditions used in the Ohasama study [9, 14].

Identification of studies

Based on our knowledge of the literature, we identified five large-scale studies in Japan with self-measured home blood pressure that met the aforementioned conditions: the Hisayama study (Hisayama) [20, 21], the Nagahama study (Nagahama) [22], the Ohasama study (Hanamaki) [23, 24], the Shiga Epidemiological Study of Subclinical Atherosclerosis (SESSA; Kusatsu) [25], and the western region of the Septuagenarians, Octogenarians, and Nonagenarians Investigation with Centenarians (SONIC) study (Asago and Itami) [26, 27]. Investigators of the SESSA and SONIC performed random sampling of the catchment area for the enrollment of the cohort, and Hisayama, Nagahama, and Ohasama investigators conducted broad participant recruitment during annual health check-ups and/or by municipal publicity. To ensure the comprehensiveness of the included population, we searched the PubMed database in December 2017 using the search term “((home BP) OR self-measured BP) AND population AND Japan,” yielding 78 publications. Two authors (KA and MK) independently reviewed titles and abstracts and read all papers that might meet the inclusion criteria; disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two authors and senior author (TO). Finally, no further eligible general population-based studies were found.

Blood pressure measurement

The essential conditions of home blood pressure measurement were defined according to the Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines [1]. Morning home blood pressure was measured within 1 h of waking, after urination, before breakfast, before taking antihypertensive medication, and after a few minutes of rest in a sitting position. Evening home blood pressure was measured just before going to bed, after a few minutes of rest in a sitting position. In SESSA, the evening home blood pressure was not collected. The participants were asked to self-measure blood pressure at home 1 (Nagahama, Ohasama, SESSA), 2 (SONIC), or 3 (Hisayama) times per occasion and for 7 (Nagahama, SESSA) or 28 (Hisayama, Ohasama, SONIC) days.

Home blood pressure was measured using the validated upper-arm cuff-oscillometric Omron HEM-705IT [28, 29] (Omron Healthcare Co. Ltd, Kyoto, Japan) in SESSA, and the Omron HEM-7080IC (Omron Healthcare Co. Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) in the other four cohorts. The HEM-7080IC uses the same measurement technology as the HEM-705IT [30] and recently passed the International Organization for Standardization requirements [31] for use in oldest-old individuals of ≥85 years of age [32]. In Ohasama, the HEM-7080IC was introduced in 2013, and the validated Omron HEM-747IC-N [33] (Omron Healthcare Co. Ltd, Kyoto, Japan) had been used from 2001. The measurement conditions are summarized in Table 1.

Data collection

The MDAS database is constructed and maintained at the Department of Hygiene and Public Health, Teikyo University School of Medicine (Tokyo, Japan). In accordance with current national regulations, review boards waived the requirement for ethical clearance for the secondary use of anonymized summary data to be included in the MDAS resource. The principal investigators of the five eligible studies agreed to participate in MDAS.

The information retrieved from the studies included the catchment year, the total number of participants, and the home blood pressure with pulse rate according to sex, age group, and antihypertensive drug treatment in the measurement period. Based on the predefined analysis plan, the investigators of the five cohorts provided aggregate summary statistics of participants classified according to (1) sex, (2) 10 age groups (in 5-year intervals: <40, 40–44,…, 75–79, and ≥80 years), and (3) antihypertensive drug treatment. In each classified cluster, the data on the number of participants, average age, morning and evening home blood pressures, and pulse rate with SD were collected and integrated. Home measurement values were averaged regardless of the number of measurements per occasion and number of the measurement days. The SONIC participants were 85–87 years of age, and they were assigned to the ≥80 years of age group.

Statistical analyses

For the home blood pressure and pulse rate, the average morning and evening measurements were analyzed separately. SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for database management and to perform the statistical analyses.

We conducted meta-analyses for the aggregate data. According to the assumption that the true average values differed among studies, we estimated the pooled blood pressure and pulse rate and its confidence interval from random effects models as implemented in the PROC MIXED procedure of the SAS software. Each study was weighted by the inverse of the within-study variance per classified cluster combined. Because only 69 (3.7%) participants <50 years of age took antihypertensive drugs, integrated blood pressure levels among individuals ≥50 years of age were demonstrated. We estimated the heterogeneity of home measurements in each sex-, age-, and treatment-divided cluster across individual populations using Cochran’s Q statistic, with the P value corrected by the Bonferroni method [34]. Statistical significance was set at α < 0.05 in two-sided tests.

Results

Aggregate characteristics

The characteristics of the populations according to the cohort are shown in Table 2. The weighted mean age of the 9,801 participants was 61.4 years, 5708 participants (58.2%) were women, systolic/diastolic blood pressures were 129.6/77.0 mmHg in the morning and 122.1/70.5 mmHg in the evening, and the corresponding pulse rates were 65.6 beats per minute and 68.7 beats per minute. Among the participants, 24.6% of women and 33.8% of men received antihypertensive treatment at baseline; the rate increased as the age category increased from 50–54 years of age (12.0%) to ≥80 years of age (55.1%).

Blood pressure and pulse rate in the morning and evening

The self-measured home blood pressure in the morning (Fig. 1) and in the evening (Fig. 2) and the home pulse rate (Fig. 3) in each 5-year age category are presented together with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The morning blood pressure levels were significantly higher in participants receiving antihypertensive medication than in those without medication. The blood pressure difference between those with and without antihypertensive treatment was marked in women and in the younger generation, whereas the average diastolic pressure levels were almost identical among those of ≥80 years of age, regardless of sex and antihypertensive treatment status, in both the morning (73.7–75.8 mmHg) and evening (67.1–68.9 mmHg).

The mean evening systolic (a) and diastolic (b) self-measured home blood pressure. Error bars indicate the one-sided 95% confidence interval. Heterogeneity tests among the cohorts were not significant (corrected P ≥ 0.28), with the exception of untreated men aged 60–64 years (corrected P = 0.0091) and 75–79 years (corrected P = 0.033)

The mean self-measured pulse rate in the morning (a) and evening (b). Error bars indicate the one-sided 95% confidence interval. Heterogeneity tests among the cohorts were not significant (corrected P ≥ 0.12), with the exception of untreated women aged 65–69 years (corrected P = 0.0001) in the morning measurement and untreated women aged 55–59 and 60–64 years (corrected P = 0.029 and 0.0032, respectively) in the evening measurement

The systolic blood pressure increased as the age category increased, while diastolic blood pressure tended to decrease, except in women without antihypertensive treatment. The mean morning home pulse rate was limited to 63.3–66.2 beats per minute in individuals 60–79 years of age, regardless of sex, age, and antihypertensive treatment status. Heterogeneity tests indicated that home measurement values were grossly homogenous among the study population, irrespective of their cluster, with several statistically significant differences, as noted in the figure legends.

Differences between the morning and evening measurements

The difference in home systolic/diastolic blood pressure (determined as the morning measurement minus the evening measurement) among people without antihypertensive medication, excluding those ≥80 years of age, was 5.7/5.0 mmHg in women (ranges across the cohorts, 5.3–6.8/4.7–5.4 mmHg; the Ohasama population, 6.8/5.2 mmHg) and 7.3/7.7 mmHg in men (ranges, 6.4–8.5/7.0–8.7 mmHg; the Ohasama population, 6.8/7.1 mmHg). In contrast, the difference in the home pulse rate in women and men was 2.4 (range, 1.5–3.7) beats per minute and 5.6 (range, 4.6–6.6) beats per minute, respectively, higher in the evening measurement than in the morning measurement.

The difference between morning and evening blood pressure in participants treated with antihypertensive medication (excluding those ≥80 years of age; mean age, 67.5 years) was 10.0/7.8 (ranges across the cohorts, 8.9–11.2/7.3–8.6) mmHg, which was 3.7/1.9 (ranges, 3.3–4.1/1.5–2.1) mmHg greater than that in individuals without antihypertensive treatment (mean age, 63.1 years). The discrepancy in the home pulse rate difference (determined as morning value minus evening value) was −0.8 (range, −1.1–0) beats per minute.

Discussion

We identified the current status of home blood pressure and pulse rate among the Japanese general population based on measurements that were obtained under well-defined conditions. The general impact of antihypertensive medication on the difference in home blood pressure was also assessed. We found that the home blood pressure measured in the morning was consistently higher than that measured in the evening among current Japanese populations that participated in MDAS; the pulse rate showed the opposite pattern, with the pulse rate measured in the morning being lower than that measured in the evening.

The evening home blood pressure was measured just before going to bed in all of the MDAS cohorts. The measurement period differed from other studies outside Japan in which most measurements were performed several hours before bedtime in most residents, e.g., between 17:00 and 23:00 in the Greek Didima study [13] and between 18:00 and 21:00 in the Finnish Finn-Home study [35]. The morning–evening home blood pressure difference was in contrast with previous studies. In the Didima participants, the systolic/diastolic evening home blood pressure was 1.1 (SD, 8.4)/0.1 (5.0) mmHg higher than the morning home blood pressure [13]. In the untreated Finn-Home population, the evening home blood pressure was 4.1/0.4 mmHg higher than the morning home blood pressure [35]. Home blood pressure was measured once upon waking in the morning and once before bedtime in the evening in the Tecumseh Blood Pressure Study, Michigan, US [36]. Although this measurement time period was similar to the MDAS cohorts, the evening home blood pressure among the Tecumseh untreated residents of 18–41 years of age was 3.0/0.8 mmHg higher than the morning pressure in men (n = 67) and 3.4/0.7 mmHg higher than the morning pressure in women (n = 66). Black Africans in the Nigerian Population Research on Environment Gene and Health (NIPREGH) measured home blood pressure twice in the morning at 06:00–08:00 and twice in the evening at 19:00–21:00 [37]. The morning home blood pressure among the 337 NIPREGH participants (women, 46.6%; mean age, 40.3 years; 8.3% treated with antihypertensive drugs) was 2/1 mmHg higher than the evening home blood pressure.

The evening blood pressure of the patients with antihypertensive medication in the Argentina Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires (HIBA-Home) study [38], in which the evening blood pressure was captured before supper but not before 20:00 (the eating time in Argentina is usually 20:00–23:00 [38]), was 1.1 (12.5)/2.3 (6.1) mmHg lower than the morning home blood pressure. It is a reasonable assumption that individuals under antihypertensive medication tend to show a comparably high morning home blood pressure, as supported by the Finn-Home finding in which the higher level of evening blood pressure, as previously mentioned, was minimized to 0.5/−1.4 mmHg when the subgroup of patients using antihypertensive medications was assessed [35]. The Finn-Home investigators also reported that antihypertensive drug therapy was an independent determinant of elevated morning blood pressure (P < 0.001) [39]. In addition to antihypertensive treatment, being men [14, 39], aging [38], smoking habits [38], alcohol intake [39], total cholesterol level [38], cardiovascular disease [39], sleep apnea [39], and instability of home blood pressure values represented as the standard deviation [14] independently contributed to increases in morning home blood pressure. In the Ohasama study, morning and evening blood pressure provided equally useful information for stroke risk, whereas morning hypertension, which indicates hypertension specifically observed in the morning, was a marked predictor (relative hazard, 3.35; 95% confidence intervals, 1.70–7.38) of stroke among individuals using antihypertensive medication [40]. Despite the evening measurement period, comparably high morning home blood pressure within a population would be a marker of worse conditions, as demonstrated in previous reports [38, 39], and would be further associated with cardiovascular risk [40].

The home blood pressure in the Ohasama study was self-measured under the same conditions throughout the study period, and data from the different catchment periods were separately provided to IDHOCO [12] and MDAS. During the former period of 1988–1995, which corresponded to the data provided to IDHOCO, the morning minus evening home blood pressures in individuals treated with antihypertensive medication (women, 72.1%; mean age, 66.0 years) and in individuals without antihypertensive medication (women, 63.5%; mean age, 56.1 years) were 3.3/2.2 and 1.4/1.3 mmHg, respectively [14, 41]. In the present study, based on the latter period of 2001–2017 in MDAS, the difference among individuals without antihypertensive treatment expanded. It is difficult to comment on this change because we could not find any other general population-based reports regarding the self-measured home blood pressure that were captured during in the same periods. Indoor temperatures alter the home and ambulatory blood pressure levels [42, 43], and recent improvements in air conditioning systems in the Ohasama region might have affected the discrepancy in the morning–evening home blood pressure difference. We should simply note that from 1990 to 2016, the average conventional office systolic blood pressure levels decreased by ~8 mmHg in women and 4 mmHg in men, regardless of age category [1]. Inversely, hypertension treatment rates have increased by ~10% in women and 20% in men, although the control rate (proportion of treated patients with office blood pressure <140/<90 mmHg under antihypertensive medication) has not reached 50% [1, 44]; this insufficient hypertension control rate has been reported worldwide [45]. Continual data on monitoring of the out-of-office blood pressure-based prevalence, the control rate, and the treatment status of hypertension are essential for strategies aimed at preventing hypertension and future complications.

The self-measured pulse rate at home was ≈65 beats per minute in the present Japanese general population. We did not find a sex difference in the home pulse rate, which was inconsistent with findings from another Japanese population in which it was reported that the pulse rate in women was higher than that in men regardless of age and antihypertensive treatment [44]. A recent report based on the Ohasama study demonstrated that sex differences in age-related trends in home pulse rates—which were calculated based on repeated measurement of the pulse rate during a median period of 14.5 years—were significant among individuals of 70–79 years of age but not among individuals within other age ranges [46]. Although a patient-based population, the Japan Home versus Office BP Measurement Evaluation study reported that sex differences were not a significant determinant of the home pulse rate in multivariable-adjusted models (P ≥ 0.5) [47]. It was not possible to draw any firm conclusions on the effect of antihypertensive drug agents on the pulse rate because we had no detailed information on the types of medication. A concurrent patient-based survey performed in 2003 reported that 11.7% of Japanese patients were treated with beta-blockers, which generally decreased the pulse rate [48]. We can assume that the impact of beta-blockers on the home pulse rate in the current population would be <1 beat per minute at most.

The current findings that there were >5 mmHg differences between morning and evening home blood pressures in the recent Japanese general population raise the question of which measurement should we rely on for the diagnosis of hypertension. The definition of hypertension based on self-measurement of home blood pressure is ≥135/≥85 mmHg regardless of the measurement time zone in many guidelines [1, 49, 50] because the morning–evening difference was not very large in the previous studies [9, 51] from which the definitions were established. However, there were marked morning–evening blood pressure differences according to the present study, in which home blood pressure was measured after the year 2000. If this tendency is applicable worldwide and continues, we need separate outcome-driven diagnostic thresholds for morning and evening home blood pressure, and more than several years of follow-up of the MDAS participants should be assessed.

The current MDAS can overcome the fundamental limitation of the IDHOCO project [12], as we used the same series of home blood pressure measurement devices, and participants measured their home blood pressure according to the recent guidelines [1] within a fixed time period. However, the present study should be interpreted within the content of other potential limitations. First, the present analysis is based on aggregate statistics, not individual participant data (IPD). We are therefore unable to provide the variation in blood pressure values (standard deviations), instead of the 95% confidence intervals of mean values, and the significance of the difference was tested based on crude measurements without multivariable adjustment. Conducting new clinical or epidemiological studies is becoming increasingly difficult due to a recent trend of making the study requirements stricter, and this also applies to IPD meta-analyses. However, our approach is a practical alternative in such research settings since the present study successfully demonstrated evidence of the characteristics of home blood pressure. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the analysis limits causal inferences regarding the associations that were found. Third, the time periods for which antihypertensive medications were prescribed and the dosing regimens were inconsistent. The blood pressure differences between people with and without antihypertensive medication were more marked in women than men; we cannot explain this discrepancy from the current dataset. Fourth, it is not certain whether the five integrated cohorts represent overall features of Japanese society. For instance, the percentage distribution of the study population among individuals aged 80 years or older (4.4%; Table 2) was approximately half that of the entire Japanese population (7.8%) [52]. Furthermore, we did not include metropolitan dwellers in the present study. Although representativeness within each cohort was satisfactory, that of the MDAS dataset as a whole needs improvement in the future. Fifth, seasonal changes in home blood pressure and pulse rate could not be assessed in the present study. Seasonal blood pressure changes are associated with cardiovascular complications and are mainly influenced by temperature [42, 53]. Moreover, beyond indoor temperature [43], blood pressure variation can be affected by a number of factors, including daylight hours, physical activity, psychological stress, and medications [53, 54]. The difference in morning and evening values and the impact of antihypertensive medication may have also been affected by seasonal environmental and social modifications, which should be further investigated.

In conclusion, we demonstrated the home blood pressure and pulse rate among the general Japanese population, subdivided by sex, age, and antihypertensive drug treatment. The current aggregate data are valuable as the current reference level for these home measurements, and the approach by which fine-clustered aggregate statistics were collected and integrated addresses practical issues raised in an epidemiological research setting. The main goal of MDAS is to identify conditions that affects blood pressure values and to thus identify the best practices for conducting home blood pressure measurements. In this first step, although the current findings were limited to Japanese individuals, the study helps to make medical professionals, healthcare providers, policymakers, and regular citizens aware of the importance of improving the effectiveness of home blood pressure self-measurements.

References

Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, Asayama K, Dohi Y, Hirooka Y, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1235–481.

Kokubo Y, Okamura T, Watanabe M, Higashiyama A, Ono Y, Miyamoto Y, et al. The combined impact of blood pressure category and glucose abnormality on the incidence of cardiovascular diseases in a Japanese urban cohort: the Suita Study. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:1238–43.

Ninomiya T, Kiyohara Y, Tokuda Y, Doi Y, Arima H, Harada A, et al. Impact of kidney disease and blood pressure on the development of cardiovascular disease: an overview from the Japan Arteriosclerosis Longitudinal Study. Circulation. 2008;118:2694–701.

Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Rakugi H, Miyakawa M, Mori H, Katsuya T, et al. Comparison of blood pressure values-self-measured at home, measured at an unattended office, and measured at a conventional attended office. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1726–37.

Asayama K. Observational study and participant-level meta-analysis on antihypertensive drug treatment-related cardiovascular risk. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:856–60.

Asayama K, Li Y, Franklin SS, Thijs L, O’Brien E, Staessen JA. Cardiovascular risk associated with white-coat hypertension: con side of the argument. Hypertension. 2017;70:676–82.

Imai Y, Hosaka M, Elnagar N, Satoh M. Clinical significance of home blood pressure measurements for the prevention and management of high blood pressure. Clin Exp Pharm Physiol. 2014;41:37–45.

Asayama K, Fujiwara T, Hoshide S, Ohkubo T, Kario K, Stergiou GS, et al. Nocturnal blood pressure measured by home devices: evidence and perspective for clinical application. J Hypertens. 2019;37:905–16.

Ohkubo T, Imai Y, Tsuji I, Nagai K, Kato J, Kikuchi N, et al. Home blood pressure measurement has a stronger predictive power for mortality than does screening blood pressure measurement: a population-based observation in Ohasama, Japan. J Hypertens. 1998;16:971–5.

Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Metoki H, Hoshi H, Hashimoto J, et al. Prediction of stroke by self-measurement of blood pressure at home versus casual screening blood pressure measurement in relation to the JNC-7 classification: the Ohasama study. Stroke. 2004;35:2356–61.

Yasui D, Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Kanno A, Hara A, et al. Stroke risk in treated hypertension based on home blood pressure: the Ohasama study. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:508–14.

Niiranen TJ, Thijs L, Asayama K, Johansson JK, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, et al. The International Database of HOme blood pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcome (IDHOCO): moving from baseline characteristics to research perspectives. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:1072–9.

Stergiou GS, Nasothimiou EG, Kalogeropoulos PG, Pantazis N, Baibas NM. The optimal home blood pressure monitoring schedule based on the Didima outcome study. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:158–64.

Imai Y, Nishiyama A, Sekino M, Aihara A, Kikuya M, Ohkubo T, et al. Characteristics of blood pressure measured at home in the morning and in the evening: the Ohasama study. J Hypertens. 1999;17:889–98.

Hata J, Ninomiya T, Hirakawa Y, Nagata M, Mukai N, Gotoh S, et al. Secular trends in cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in Japanese: half-century data from the Hisayama Study (1961–2009). Circulation. 2013;128:1198–205.

Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Hoshide S, Kario K, Ohya Y, Rakugi H, et al. From mercury sphygmomanometer to electric device on blood pressure measurement: correspondence of Minamata Convention on Mercury. Hypertens Res. 2016;39:179–82.

Shirasaki O, Terada H, Niwano K, Nakanishi T, Kanai M, Miyawaki Y, et al. The Japan Home-Health Apparatus Industrial Association: investigation of home-use electronic sphygmomanometers. Blood Press Monit. 2001;6:303–7.

Hozawa A, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Ugajin T, Yamaguchi J, Asayama K, et al. Prognostic value of home heart rate for cardiovascular mortality in the general population: the Ohasama study. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:1005–10.

Imai Y, Otsuka K, Kawano Y, Shimada K, Hayashi H, Tochikubo O, et al. Japanese society of hypertension (JSH) guidelines for self-monitoring of blood pressure at home. Hypertens Res. 2003;26:771–82.

Oishi E, Ohara T, Sakata S, Fukuhara M, Hata J, Yoshida D, et al. Day-to-day blood pressure variability and risk of dementia in a general japanese elderly population: The Hisayama Study. Circulation. 2017;136:516–25.

Sakata S, Hata J, Fukuhara M, Yonemoto K, Mukai N, Yoshida D, et al. Morning and evening blood pressures are associated with intima-media thickness in a general population—The Hisayama Study. Circ J. 2017;81:1647–53.

Tabara Y, Matsumoto T, Murase K, Setoh K, Kawaguchi T, Nagashima S, et al. Day-to-day home blood pressure variability and orthostatic hypotension: The Nagahama Study. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31:1278–85.

Matsumoto A, Satoh M, Kikuya M, Ohkubo T, Hirano M, Inoue R, et al. Day-to-day variability in home blood pressure is associated with cognitive decline: the Ohasama study. Hypertension. 2014;63:1333–8.

Satoh M, Hosaka M, Asayama K, Kikuya M, Inoue R, Metoki H, et al. Aldosterone-to-renin ratio and nocturnal blood pressure decline assessed by self-measurement of blood pressure at home: the Ohasama Study. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2014;36:108–14.

Hisamatsu T, Miura K, Ohkubo T, Arima H, Fujiyoshi A, Satoh A, et al. Home blood pressure variability and subclinical atherosclerosis in multiple vascular beds: a population-based study. J Hypertens. 2018;36:2193–203.

Ryuno H, Kamide K, Gondo Y, Kabayama M, Oguro R, Nakama C, et al. Longitudinal association of hypertension and diabetes mellitus with cognitive functioning in a general 70-year-old population: the SONIC study. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:665–70.

Godai K, Kabayama M, Gondo Y, Yasumoto S, Sekiguchi T, Noma T, et al. Day-to-day blood pressure variability is associated with lower cognitive performance among the Japanese community-dwelling oldest-old population: the SONIC study. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:404–11.

Coleman A, Freeman P, Steel S, Shennan A. Validation of the Omron 705IT (HEM-759-E) oscillometric blood pressure monitoring device according to the British Hypertension Society protocol. Blood Press Monit. 2006;11:27–32.

El Assaad MA, Topouchian JA, Asmar RG. Evaluation of two devices for self-measurement of blood pressure according to the international protocol: the Omron M5-I and the Omron 705IT. Blood Press Monit. 2003;8:127–33.

dabl® Educational Trust Limited. dabl Educational Trust. 2004. http://dableducational.org/. Accessed 2 Apr 2020.

International Organization for Standardization. ISO 81060-2:2013, non-invasive sphygmomanometers—part 2: clinical investigation of automated measurement type. 2013. https://www.iso.org/standard/57977.html. Accessed 2 Apr 2020.

Godai K, Kabayama M, Saito K, Asayama K, Yamamoto K, Sugimoto K, et al. Validation of an automated home blood pressure measurement device in oldest-old populations. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:30–5.

Chonan K, Kikuya M, Araki T, Fujiwara T, Suzuki M, Michimata M, et al. Device for the self-measurement of blood pressure that can monitor blood pressure during sleep. Blood Press Monit. 2001;6:203–5.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. BMJ. 1995;310:170.

Niiranen TJ, Jula AM, Kantola IM, Reunanen A. Comparison of agreement between clinic and home-measured blood pressure in the Finnish population: the Finn-HOME Study. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1549–55.

Mejia AD, Julius S, Jones KA, Schork NJ, Kneisley J. The Tecumseh Blood Pressure Study. Normative data on blood pressure self-determination. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1209–13.

Odili AN, Abdullahi B, Nwankwo AM, Asayama K, Staessen JA. Characteristics of self-measured home blood pressure in a Nigerian urban community: the NIPREGH study. Blood Press Monit. 2015;20:260–5.

Aparicio LS, Barochiner J, Cuffaro PE, Alfie J, Rada MA, Morales MS, et al. Determinants of the morning-evening home blood pressure difference in treated hypertensives: The HIBA-Home Study. Int J Hypertens. 2014;2014:569259.

Johansson JK, Niiranen TJ, Puukka PJ, Jula AM. Factors affecting the difference between morning and evening home blood pressure: the Finn-Home study. Blood Press. 2011;20:27–36.

Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Obara T, Metoki H, Inoue R, et al. Prediction of stroke by home “morning” versus “evening” blood pressure values: the Ohasama study. Hypertension. 2006;48:737–43.

Imai Y, Ohkubo T, Tsuji I, Hozawa A, Nagai K, Kikuya M, et al. Relationships among blood pressures obtained using different measurement methods in the general population of Ohasama, Japan. Hypertens Res. 1999;22:261–72.

Yatabe J, Yatabe MS, Morimoto S, Watanabe T, Ichihara A. Effects of room temperature on home blood pressure variations: findings from a long-term observational study in Aizumisato Town. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:785–7.

Saeki K, Obayashi K, Iwamoto J, Tone N, Okamoto N, Tomioka K, et al. Stronger association of indoor temperature than outdoor temperature with blood pressure in colder months. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1582–9.

Asayama K, Hozawa A, Taguri M, Ohkubo T, Tabara Y, Suzuki K, et al. Blood pressure, heart rate, and double product in a pooled cohort: the Japan Arteriosclerosis Longitudinal Study. J Hypertens. 2017;35:1808–15.

Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Banegas JR, Giampaoli S, Hense HW, Joffres M, et al. Hypertension prevalence and blood pressure levels in 6 European countries, Canada, and the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:2363–9.

Satoh M, Metoki H, Asayama K, Murakami T, Inoue R, Tsubota-Utsugi M, et al. Age-related trends in home blood pressure, home pulse rate, and day-to-day blood pressure and pulse rate variability based on longitudinal cohort data: the Ohasama study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012121.

Obara T, Ohkubo T, Komai R, Asayama K, Kikuya M, Metoki H, et al. Control of home heart rate and home blood pressure levels in treated patients with hypertension: the J-HOME study. Blood Press Monit. 2007;12:289–95.

Ohkubo T, Obara T, Funahashi J, Kikuya M, Asayama K, Metoki H, et al. Control of blood pressure as measured at home and office, and comparison with physicians’ assessment of control among treated hypertensive patients in Japan: First Report of the Japan Home versus Office Blood Pressure Measurement Evaluation (J-HOME) study. Hypertens Res. 2004;27:755–63.

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021–104.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13–e115.

Niiranen TJ, Asayama K, Thijs L, Johansson JK, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, et al. Outcome-driven thresholds for home blood pressure measurement: international database of home blood pressure in relation to cardiovascular outcome. Hypertension. 2013;61:27–34.

Statistics Bureau of Japan. Population and households of Japan 2015. 2015. https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/kokusei/2015/poj/mokuji.html. Accessed 22 May 2020.

Modesti PA, Rapi S, Rogolino A, Tosi B, Galanti G. Seasonal blood pressure variation: implications for cardiovascular risk stratification. Hypertens Res. 2018;41:475–82.

Hanazawa T, Asayama K, Imai Y, Ohkubo T. Response to Yatabe et al. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:789–90.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deepest appreciation to all of the MDAS study collaborators for their valuable contribution. We thank the staff of Teikyo University for their valuable help.

Funding

This study was also supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (17H04126) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Omron Healthcare provided research support to KA, KK, and TO. Daiichi Sankyo provided honoraria and research support to KK. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Asayama, K., Tabara, Y., Oishi, E. et al. Recent status of self-measured home blood pressure in the Japanese general population: a modern database on self-measured home blood pressure (MDAS). Hypertens Res 43, 1403–1412 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0530-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0530-1

Keywords

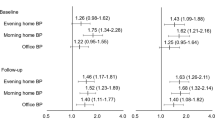

This article is cited by

-

Predictive power of home blood pressure in the evening compared with home blood pressure in the morning and office blood pressure before treatment and in the on-treatment follow-up period: a post hoc analysis of the HOMED-BP study

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

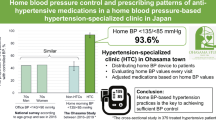

In-office and out-of-office blood pressure measurement

Journal of Human Hypertension (2021)

-

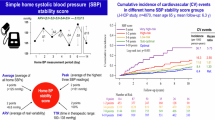

Difference between morning and evening home blood pressure and cardiovascular events: the J-HOP Study (Japan Morning Surge-Home Blood Pressure)

Hypertension Research (2021)