Abstract

Early intervention to manage high blood pressure (BP) in young adulthood is a promising approach for the prevention of future cardiovascular diseases. We aimed to examine the ability of childhood health information to predict the incidence of young adults with high BP. This cohort study included baseline clinical data of Japanese individuals aged 12–13 years. A total of 1129 participants were followed up for an average of 8.6 years. We examined the association of childhood variables consisting of body weight, body mass index, systolic BP, white blood cell count, red blood cell count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelet count, uric acid, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol with the development of high BP defined as ≥120/80 mmHg at 18–22 years old. At follow-up, the prevalence of high BP was 42.2% in men and 7.7% in women. Young men with high BP had childhood baseline characteristics that included higher body weight, body mass index, systolic BP, red blood cell count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and uric acid than normotensive men. Young women with high BP had higher body weight, systolic BP, and uric acid at baseline. Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that a model including body weight, systolic BP, hematocrit, and uric acid had the highest predictive power (AUC 0.65 [95% CI, 0.62–0.69]) for men, and a model including body weight, systolic BP, and uric acid had the highest predictive power (AUC 0.70 [95% CI, 0.58–0.81]) for women. Comprehensive childhood health information contributes to the prediction of high BP in young adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is a leading global cause of cardiovascular disease and mortality [1]. There is a continuous graded increase in cardiovascular risks in relation to blood pressure (BP), even at levels below 140/90 mmHg [2], which is the worldwide threshold for the diagnosis of hypertension for people younger than 65. The 2017 American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) BP guidelines define four categories of BP: normal BP, defined as systolic BP of <120 mmHg and diastolic BP of <80 mmHg; elevated BP, defined as 120–129/<80 mmHg; stage 1 hypertension, defined as 130–139/80–89 mmHg; and stage 2 hypertension, defined as ≥140/≥90 mmHg [3]. These categories are based on data reporting a gradient of progressively higher risk of cardiovascular diseases as BP goes from normal BP to the other BP categories.

Sufficient evidence has been accumulated to indicate the association of the ACC/AHA BP categories with cardiovascular risk in middle-aged and elderly populations [4], and even in young adults, a causal association of elevated BP with future cardiovascular disease has been reported, with a prospective cohort study showing a positive correlation between higher baseline BP categories in young adults and the incidence of cardiovascular diseases later in life [5]. In general, the earlier we correct reversible risk factors, the more effectively we can prevent future cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, early identification of elevated BP and intervention in a high-risk population will contribute to overcoming cardiovascular diseases.

Childhood BP has been identified as a risk factor for hypertension in young adults [6,7,8,9], and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that BP should be measured annually in children and adolescents [10]. However, the literature contains little information on the association between comprehensive risk assessment factors, including BP, anthropometric measurements, and laboratory data in childhood and BP status in young adults. Therefore, here, we examined the association between comprehensive childhood health information obtained from medical checkups and the development of high BP in young adults.

Methods

Study population and data sources

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Subcommittee of the Keio University Research Ethics Committee [approval number 20-001]. The data from participants who refused to provide data were excluded at data collection. Informed consent was obtained using opt-out methods, according to the local ethics committee guidelines.

This retrospective cohort study included asymptomatic Japanese male and female junior high school students aged 12–13 years who had attended an annual medical checkup performed by the Keio University Health Center during the period from 2008 to 2009. All participants were enrolled in four junior high schools in metropolitan and suburban Tokyo, Japan. Because the aim of the study was to evaluate the association of childhood risk factors with high BP in young adults, we excluded children with a previous clinical diagnosis of hypertension or conditions that may cause secondary hypertension; such conditions included pediatric and congenital heart diseases receiving medical treatment, congenital aortic malformations that had previously received surgical treatment, congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract, glomerulonephritis treated with immunosuppressive therapy, chronic kidney disease stages 4 and 5, and endocrine disorders receiving medical treatment. The 1129 participants were followed up for an average of 8.6 years (range: 6.0–9.0 years). In the present study, “young adult” is defined as a participant between 18 and 22 years of age.

Measurements

Childhood predictive variables were height, body weight, body mass index (BMI), systolic and diastolic BPs, white blood cell (WBC) count, red blood cell (RBC) count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelet count, uric acid, total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLC), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLC). LDLC was measured in 2009, but not in 2008.

Standing height and body weight were measured without shoes and outer clothing. BMI was calculated as body weight divided by the square of the height (kg/m2). Childhood BMI was categorized into normal weight (<85th percentile) and overweight (≥85th percentile) according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cutoff point [11, 12] based on BMI percentiles from BMI reference data for Japanese children [13, 14].

BP was measured by a trained nurse using an electronic sphygmomanometer (BP-103i II; Omron Colin Co, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) on the right arm in a relaxed, sitting position. A 12-cm-wide cuff for an arm circumference of 22–32 cm was used. If the measured BP was >135/80 mmHg in a junior high school medical checkup (2008–2009) or ≥140/90 mmHg in young adulthood (2014–2018), the BP was remeasured. If BP was measured twice on one occasion, the last measurement was used for the analysis. Childhood BP was categorized as normal (<90th percentile), elevated (≥90th percentile to <95th percentile or 120/80 mmHg to <95th percentile, whichever was lower), or hypertensive (≥95th percentile or 130/80 mmHg, whichever was lower) according to the AAP Clinical Practice Guideline [10]. Annual BP measurements in young adults were averaged and then categorized into a normal BP group or a high BP group consisting of young adults with elevated BP and hypertension determined on the basis of the 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline [3].

Nonfasting blood samples were collected from the median cubital, basilic, or cephalic vein. HDLC and LDLC were analyzed by direct assay, and TC was measured by the cholesterol dehydrogenase-UV method. Serum uric acid was measured by the uricase–peroxidase method.

Statistical analyses

Childhood baseline characteristics and BP measurement and category during follow-up in young adults were summarized by using means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables and by frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. Baseline comparisons between participants with normal BP and with high BP in young adulthood were based on two-sample t-tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables.

Both male and female crude odds ratios for young adults with high BP were examined using logistic regression analysis. When childhood variables were collinear, we entered the most representative variable into multivariable logistic regression models to estimate the adjusted odds ratio for young adults with high BP.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was also performed with a stepwise method (0.05 for entry and 0.10 for removing the variables) to determine independent predictors of young-adult high BP to construct predictive models of young-adult high BP. When independent variables are highly correlated with each other, we selected only the most representative variable. The discriminative ability of each prediction model was evaluated with the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, and Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) was applied for selecting variables.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software ver. 25.0 (SPSS Statistics 25, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Statistical significance was defined as a p value <0.05 using two-sided tests.

Results

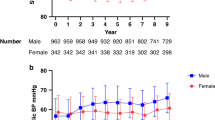

As shown in Fig. 1, a total of 1304 students underwent the baseline examination in annual medical checkups performed during the period from 2008 to 2009. At the baseline examination, 107 students were excluded because of incomplete data collection. Of the 1197 participants, we excluded three participants who refused to provide their medical checkup data and three participants who had conditions that might cause secondary hypertension: one participant had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, one participant had type 1 diabetes mellitus, and one participant was receiving a daily dose of methimazole to treat hyperthyroidism. We also excluded 62 participants (5.2%) who were lost to follow-up. The final analysis set comprised 1129 participants whose baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. At baseline, the mean age was 12.6 years [SD, 0.3], 27.5% were female, 8.1% were categorized as having elevated BP, and 8.0% were categorized as having hypertension.

Flow chart for the participant selection. A total of 1304 students underwent the baseline examination in an annual medical checkup performed during the period from 2008 to 2009. At the baseline examination, 107 students were excluded because of incomplete data collection. Of the 1197 participants, three participants were excluded because they refused to provide their medical checkup data, and three participants were excluded because they had conditions that might cause secondary hypertension. The final analysis set comprised 1129 participants

At follow-up, the prevalence of the high BP category consisting of elevated BP and hypertension was 42.2% (n = 346) in male young adults and 7.7% (n = 24) in female young adults (Table 2). The mean systolic/diastolic BP was 117.8 [SD, 10.1]/63.6 [SD, 6.1] mmHg in men and 105.2 [SD, 9.6]/59.6 [SD, 5.5] mmHg in women. Comparison of the baseline characteristics of male participants with normal BP and those with high BP in young adulthood revealed statistically significant differences in childhood baseline characteristics, including height, weight, BMI, overweight status, systolic BP, diastolic BP, elevated BP and hypertension, RBC counts, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and uric acid (Table 3). Differences in childhood baseline characteristics between female participants with normal BP and those with high BP in young adulthood included height, weight, systolic BP, diastolic BP, and uric acid (Table 3).

Prediction model for young-adult high blood pressure

The male and female crude odds ratios for young adults with high BP according to childhood variables are shown in Table 4. Childhood overweight showed the largest odds ratio for young adults with high BP, followed by elevated BP and hypertension in both men and women. In addition to anthropometric measurements and BP, RBCs, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and uric acid in men and RBCs, hemoglobin, and hematocrit in women were significantly associated with young adults with high BP. In a multivariable logistic analysis, the independent predictors of young adults’ high BP included childhood body weight, systolic BP, and hematocrit in men (Table 5). In women, no childhood variables reached statistical significance in the multivariable regression model (Table 5).

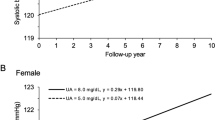

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was also performed with a stepwise method to determine independent predictors that were used to construct predictive models of young adults with high BP. Childhood baseline factors included in the stepwise selection were body weight, systolic BP, WBCs, hematocrit, platelets, uric acid, TC, and HDLC. Stepwise analysis indicated that among childhood variables, body weight (odds ratio for a 1-SD increase: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.21–1.75), systolic BP (1.25, 95% CI: 1.07–1.47), hematocrit (1.17, 95% CI: 1.00–1.40), and uric acid (0.93, 95% CI: 0.79–1.09) were independent predictors of young-adult high BP in men, whereas body weight (1.46, 95% CI: 0.94–2.26), systolic BP (1.46, 95% CI: 0.93–2.28), and uric acid (2.42, 95% CI: 0.83–7.08) were predictors in women. We created three logistic regression models using stepwise selection and assessed their predictive efficacies by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). The model including body weight, systolic BP, hematocrit, and uric acid had the highest predictive power in men (AUC 0.654, 95% CI 0.616–0.692) and presented a small AIC value (AIC 1065.9). The model including body weight, systolic BP, and uric acid had the highest predictive power (AUC 0.696, 95% CI: 0.583–0.810) and a small AIC value (AIC 163.5) in women (Fig. 2).

Receiver operating characteristic curve illustrating the ability of childhood measurements to predict high blood pressure at young adulthood. Receiver operating characteristic curves indicate the predictive efficacies of logistic regression models. A The male model included body weight, systolic blood pressure, hematocrit, and uric acid. B The female model included body weight, systolic blood pressure, and uric acid. AUC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of healthy Japanese participants, childhood health information, including BP, body weight, and laboratory data, predicted the development of high BP in young adulthood. Recent accumulated evidence has shown a causal relationship between young-adult BP and cardiovascular diseases in middle age [5, 15]. A large retrospective cohort study showed that compared with normotensive people, there is an increased risk of mortality from coronary heart disease in people who had elevated BP or stage 1 hypertension (systolic BP 120–139 mmHg and/or diastolic BP 80–89 mmHg) at a mean age of 18.3 years [15]. Moreover, a prospective cohort study also found a gradient of progressively higher risk of cardiovascular diseases, including coronary heart diseases, stroke, heart failure, and peripheral artery diseases, in young adults as BP ranges from normal BP to the other BP categories [5]. Although there is no evidence that directly proves that childhood intervention has a preventive effect on young adults with high BP, in general, targeted prevention strategies that focus on high-risk individuals are more efficient for BP reduction than population-based strategies [3]. Therefore, early identification of the population at high risk for young-adult high BP will contribute to the prevention of young-adult high BP, including not only hypertension but also elevated BP, and a subsequent reduction in risks of prospective cardiovascular diseases.

There have been a few studies that have examined the association between risk assessment factors measured in childhood, including both anthropometric measurements and laboratory data, and BP status in young adults: one study included anthropometric data and uric acid but no other laboratory parameters [16], and three studies included anthropometric and laboratory data without hematologic data or uric acid [6, 7, 9]. The present study is the first to examine the association between BP status in young adults and a comprehensive set of risk assessment factors composed of anthropometric and laboratory parameters, including hematologic data, uric acid, and lipids.

In terms of individual risk factors, previous studies have shown an association between childhood BP and young-adult BP [6, 7]. In the Atherosclerotic Risk in Young Adults (ARYA) study that examined the association of BP, anthropometric measures, serum lipids, and plasma glucose in adolescents with high BP in young adults, BP screening in adolescents was an efficient method for the prediction of young-adult hypertension (odds ratio for a 1-mmHg increase in systolic BP: 1.04) [6]. The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study, which was a longitudinal study aimed at evaluating the causal association of childhood physical and environmental factors with young-adult hypertension, also showed that BP was a strong childhood predictor for the risk of young-adult hypertension (odds ratio for a 1-SD increase: 1.67) [7]. Consistent with the results of the ARYA study and the Young Finns study, childhood systolic BP in the present study showed a large odds ratio for high BP in young adults (odds ratio for a 1-SD increase: males 1.25, females 1.46).

In both the ARYA study and the Young Finns study, no contribution of lipid metabolism to the prediction of adult hypertension was found [6, 7]. In the present study, we also did not find any clinical utility of serum lipids (TC, HDLC, and LDLC) for the detection of prospective high BP. A previous study has shown that triglycerides are consistently high from childhood through adulthood in young adults with high BP [17]. On the other hand, LDLC and HDLC levels in childhood are not associated with prospective high BP in adulthood [17]. The absence of data concerning triglycerides may be one limitation of the present study.

The lack of information on family history and birth status may be another limitation. In previous research on BP trajectories from children to young adults, a family history of high BP, being the first born, and low birth weight have been associated with the hypertensive trajectory group in comparison with the normal BP trajectory group [8]. Parental hypertension, parental occupational status, and genetic risk score based on single-nucleotide polymorphisms were also predictors of adult hypertension in the Young Finns study [7].

In the present study, height, weight, BMI, and overweight status in childhood were positively associated with the high BP category in young adulthood. Therefore, childhood anthropometric indices are thought to be strong predictive factors of young-adult high BP. Previous studies have shown a significant relationship between childhood BMI and young-adult BP [18, 19]. Although the detailed mechanisms underlying this relationship have not been fully elucidated, greater trunk fat mass in childhood seems to predict subsequent adolescent BP levels [20]. Central fat distribution is associated with low serum adiponectin levels [21], and a decrease in adiponectin levels is associated with an increased risk of hypertension [22]. On the other hand, there are limited data regarding the association between childhood height and BP in adulthood [23]. The prognostic power of childhood height for adult hypertension is weaker than that of childhood weight and at least partially depends on childhood BP [23].

The role of serum uric acid in predicting the development of high BP in young adults is another finding of this study. Serum uric acid levels are well known to be correlated with BP in children and adolescents with primary hypertension [24] and in adults independent of alcohol drinking status [25]. The association between serum uric acid level and the incidence of hypertension is found in young adults but not in elderly adults [26]. In addition, lowering uric acid with allopurinol reduces BP in hypertensive adolescents with hyperuricemia [27]. In terms of predictive value, the Bogalusa Heart Study has suggested that childhood uric acid is a predictor of adulthood systolic BP and diastolic BP, although the correlation of childhood uric acid with systolic BP and diastolic BP varies with race and sex [16]. In another study conducted in Taiwan, a high uric acid level (≥7.3 mg/dl for males and ≥6.2 mg/dl for females) was a predictive factor for hypertension after 10 years of follow-up in Asian adolescents [28]. Although its causal role in the development of hypertension is uncertain, uric acid contributes to increasing BP via activation of the renin–angiotensin system [29], decreasing NO synthase [29], and inducing endothelial dysfunction [30] and vasoconstriction [31]. Recently, elevated serum uric acid levels were indicated as a risk factor for stroke and coronary heart disease mortality in a Japanese population [32]. Therefore, the serum uric acid level in the young may have the potential to be an effective biomarker for identifying persons at risk of both hypertension and cardiovascular diseases.

The present study also suggested a sex difference in the predictive factors associated with high BP in young adults. Childhood baseline comparisons showed that RBCs, hemoglobin, and hematocrit in future normotensives were higher than those in the high BP group among male participants but not among females (Table 3). In addition, in the logistic regression models, stepwise selection included hematocrit for men but not for women. Cross-sectional studies show that hematocrit is positively associated with systolic BP and diastolic BP in both men and women [33], and although the predictive value of the hematocrit level in the detection of future high BP has not been fully elucidated among women, higher hematocrit levels are known to predict hypertension in middle-aged men [34, 35]. In general, hematocrit levels among females are lower and are possibly affected by menstruation. Furthermore, in the present study, insufficient statistical power due to the limited number of young women with high BP also affected the association between childhood hematocrit levels and future high BP in women.

In the present study, childhood systolic BP, body weight, and uric acid were predictors for high young-adult BP in both men and women, and hematocrit was also included in a predictive model for men. Comprehensive risk assessment including not only anthropometric data but also biochemical and hematologic parameters improves the predictive value for early-onset high BP. Our findings indicating the association between a comprehensive set of risk assessment factors and high BP in young adulthood will contribute to the early identification of the high-risk population and will allow early intervention for the prevention of prospective cardiovascular diseases.

The present study has several limitations. First, the eligibility was restricted to Japanese children living in an urban area. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to other racial and ethnic groups. Second, we could not completely eliminate the “white-coat phenomenon” because neither home BP measurement nor ambulatory BP monitoring measurement was available in this study. Third, we could not obtain information on family history of hypertension or birth status despite its potential utility for predicting hypertension. A fourth limitation was the lack of metabolic factors examined, such as fasting glucose, HbA1c, and triglycerides, which are known to contribute to an increased risk of metabolic syndrome, because of the retrospective dataset. Fifth, we could not obtain information on menstruation in females. Therefore, there is a possibility that menstruation affects hematologic parameters such as RBC count, hemoglobin, and hematocrit. In the future, a prospective study including multiple races, using out-of-office BP measurements and any other metabolic variables will provide new insights into our further understanding of the association between childhood health information and young-adult BP.

In conclusion, comprehensive childhood health information that can be obtained from medical checkups, including BP, anthropometric measures, and laboratory parameters, can contribute to the prediction of future high BP in young adults.

References

GBD 2016 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1345–422.

Rapsomaniki E, Timmis A, George J, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Shah AD, Denaxas S, et al. Blood pressure and incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: lifetime risks, healthy life-years lost, and age-specific associations in 1.25 million people. Lancet. 2014;383:1899–911.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018;138:e484–594.

Qi Y, Han X, Zhao D, Wang W, Wang M, Sun J, et al. Long-term cardiovascular risk associated with stage 1 hypertension defined by the 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1201–10.

Yano Y, Reis JP, Colangelo LA, Shimbo D, Viera AJ, Allen NB, et al. Association of blood pressure classification in young adults using the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Blood Pressure Guideline with cardiovascular events later in life. JAMA. 2018;320:1774–82.

Vos LE, Oren A, Bots ML, Gorissen WH, Grobbee DE, Uiterwaal CS. Does a routinely measured blood pressure in young adolescence accurately predict hypertension and total cardiovascular risk in young adulthood? J Hypertens. 2003;21:2027–34.

Juhola J, Oikonen M, Magnussen CG, Mikkila V, Siitonen N, Jokinen E, et al. Childhood physical, environmental, and genetic predictors of adult hypertension: the cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Circulation. 2012;126:402–9.

Theodore RF, Broadbent J, Nagin D, Ambler A, Hogan S, Ramrakha S, et al. Childhood to early-midlife systolic blood pressure trajectories: early-life predictors, effect modifiers, and adult cardiovascular outcomes. Hypertension. 2015;66:1108–15.

Urbina EM, Khoury PR, Bazzano L, Burns TL, Daniels S, Dwyer T, et al. Relation of blood pressure in childhood to self-reported hypertension in adulthood. Hypertension. 2019;73:1224–30.

Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, Blowey D, Carroll AE, Daniels SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171904.

Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, et al. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002;11:1–190.

Barlow SE, Expert C. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S164–92.

Kato N, Sato K, Takimoto H, Sudo N. BMI for age references for Japanese children–based on the 2000 growth survey. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2008;20(Suppl):118–27.

Kato N, Takimoto H, Sudo N. The cubic functions for spline smoothed L, S and M values for BMI reference data of Japanese children. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol. 2011;20:47–9.

Gray L, Lee IM, Sesso HD, Batty GD. Blood pressure in early adulthood, hypertension in middle age, and future cardiovascular disease mortality: HAHS (Harvard Alumni Health Study). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2396–403.

Alper AB Jr., Chen W, Yau L, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS, Hamm LL. Childhood uric acid predicts adult blood pressure: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Hypertension. 2005;45:34–8.

Srinivasan SR, Myers L, Berenson GS. Changes in metabolic syndrome variables since childhood in prehypertensive and hypertensive subjects: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Hypertension. 2006;48:33–9.

Field AE, Cook NR, Gillman MW. Weight status in childhood as a predictor of becoming overweight or hypertensive in early adulthood. Obes Res. 2005;13:163–9.

Rademacher ER, Jacobs DR Jr., Moran A, Steinberger J, Prineas RJ, Sinaiko A. Relation of blood pressure and body mass index during childhood to cardiovascular risk factor levels in young adults. J Hypertens. 2009;27:1766–74.

Kouda K, Ohara K, Fujita Y, Nakamura H, Iki M. Trunk-to-peripheral fat ratio predicts subsequent blood pressure levels in pubertal children with relatively low body fat- three-year follow-up study. Circ J. 2016;80:1838–45.

Cnop M, Havel PJ, Utzschneider KM, Carr DB, Sinha MK, Boyko EJ, et al. Relationship of adiponectin to body fat distribution, insulin sensitivity and plasma lipoproteins: evidence for independent roles of age and sex. Diabetologia. 2003;46:459–69.

Kim DH, Kim C, Ding EL, Townsend MK, Lipsitz LA. Adiponectin levels and the risk of hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2013;62:27–32.

Cook NR, Gillman MW, Rosner BA, Taylor JO, Hennekens CH. Prediction of young adult blood pressure from childhood blood pressure, height, and weight. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:571–9.

Feig DI, Johnson RJ. Hyperuricemia in childhood primary hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:247–52.

Tatsumi Y, Asayama K, Morimoto A, Satoh M, Sonoda N, Miyamatsu N, et al. Hyperuricemia predicts the risk for developing hypertension independent of alcohol drinking status in men and women: the Saku study. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:442–9.

Lee SW, Kim HC, Nam C, Lee HY, Ahn SV, Oh YA, et al. Age-differential association between serum uric acid and incident hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:428–37.

Feig DI, Soletsky B, Johnson RJ. Effect of allopurinol on blood pressure of adolescents with newly diagnosed essential hypertension: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300:924–32.

Sun HL, Pei D, Lue KH, Chen YL. Uric acid levels can predict metabolic syndrome and hypertension in adolescents: a 10-year longitudinal study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0143786.

Mazzali M, Hughes J, Kim YG, Jefferson JA, Kang DH, Gordon KL, et al. Elevated uric acid increases blood pressure in the rat by a novel crystal-independent mechanism. Hypertension. 2001;38:1101–6.

Khosla UM, Zharikov S, Finch JL, Nakagawa T, Roncal C, Mu W, et al. Hyperuricemia induces endothelial dysfunction. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1739–42.

Sanchez-Lozada LG, Tapia E, Santamaria J, Avila-Casado C, Soto V, Nepomuceno T, et al. Mild hyperuricemia induces vasoconstriction and maintains glomerular hypertension in normal and remnant kidney rats. Kidney Int. 2005;67:237–47.

Sakata S, Hata J, Honda T, Hirakawa Y, Oishi E, Shibata M, et al. Serum uric acid levels and cardiovascular mortality in a general Japanese population: the Hisayama Study. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:560–8.

Cirillo M, Laurenzi M, Trevisan M, Stamler J. Hematocrit, blood pressure, and hypertension. The Gubbio Population Study. Hypertension. 1992;20:319–26.

Jae SY, Kurl S, Laukkanen JA, Heffernan KS, Choo J, Choi YH, et al. Higher blood hematocrit predicts hypertension in men. J Hypertens. 2014;32:245–50.

Strand A, Gudmundsdottir H, Hoieggen A, Fossum E, Bjornerheim R, Os I, et al. Increased hematocrit before blood pressure in men who develop hypertension over 20 years. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2007;1:400–6.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Keio University Academic Development Funds for Joint Research (TA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Azegami, T., Uchida, K., Arima, F. et al. Association of childhood anthropometric measurements and laboratory parameters with high blood pressure in young adults. Hypertens Res 44, 711–719 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00615-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00615-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Longitudinal impact of weight change on blood pressure in University students

Hypertension Research (2025)

-

Pediatric blood pressure category predicts longitudinal blood pressure change in adolescence and early adulthood

Pediatric Research (2023)

-

Update in uric acid, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Impact of hyperuricemia on chronic kidney disease and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

Update on Hypertension Research in 2021

Hypertension Research (2022)