Abstract

Low ankle-brachial index (ABI) and high ABI difference (ABID) are each associated with poor prognosis. No study has assessed the ability of the combination of low ABI and high ABID to predict survival. We created an ABI score by assigning 1 point for ABI < 0.9 and 1 point for ABID ≥ 0.17 and examine the ability of this ABI score to predict mortality. We included 941 patients scheduled for echocardiographic examination. The ABI was measured using an ABI-form device. ABID was calculated as |right ABI–left ABI|. Among the 941 subjects, the prevalence of ABI < 0.9 and ABID ≥ 0.17 was 6.1% and 6.8%, respectively. Median follow-up to mortality was 93 months. There were 87 cardiovascular and 228 overall deaths. All ABI-related parameters, including ABI, ABID, ABI < 0.9, ABID ≥ 0.17, and ABI score, were significantly associated with overall and cardiovascular mortality in the multivariable analysis (P ≤ 0.009). Further, in the direct comparison of multivariable models, the basic model + ABI score was the best at predicting overall and cardiovascular mortality among the five ABI-related multivariable models (P ≤ 0.049). Hence, the ABI score, a combination of ABI < 0.9 and ABID ≥ 0.17, should be calculated for better mortality prediction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ankle-brachial index (ABI) has been used for many years to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate the severity of peripheral artery occlusion disease [1, 2]. ABI < 0.9 has been well proven to be a useful prognostic parameter in different patient populations, such as patients with chronic kidney disease [3,4,5], patients with acute coronary syndrome [6], older patients [7], and patients after transcatheter aortic valve replacement [8].

Recently, the ABI difference (ABID), calculated as |right ABI–left ABI|, has also been proven to be positively correlated with increased mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events in patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis [9] and patients with acute ischemic stroke [10]. However, no study has assessed the ability of the combination of low ABI and high ABID to predict survival. In the present study, we created an ABI score, which was calculated by assigning 1 point for ABI < 0.9 and 1 point for ABID ≥ 0.17. The aim of this study was to examine the ability of ABI score to predict overall and cardiovascular mortality and compare ABI score and other ABI-related parameters on their ability to predict overall and cardiovascular mortality.

Materials and methods

Study population

The study patients were randomly selected from a group of subjects scheduled for echocardiographic examination at our hospital (Kaohsiung Municipal Siaogang Hospital) from March 2010 to March 2012 due to abnormal electrocardiographic findings, cardiomegaly on chest X ray, abnormal cardiac physical examination, dyspnea and chest pain, heart failure, or complicated hypertension or to assess their preoperative cardiac function. Patients with significant aortic or mitral valve disease, atrial fibrillation, inadequate echocardiographic image visualization, or hemodialysis were excluded. In addition, seven patients with failed ABI measurements due to limb amputation (n = 3) or noncooperation (n = 4) were excluded from the final analysis. We did not include all patients consecutively because ABI must begin to be measured within 10 min after the completion of echocardiographic examination. Finally, 941 patients were enrolled. This study conformed with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. All study subjects provided written informed consent.

Assessment of ABI

The ABI value was assessed using an ABI-form device (VP1000, Colin, Aichi, Japan), which automatically and simultaneously measures blood pressure in both arms and ankles by an oscillometric method [11, 12]. ABI was calculated as the ratio of the ankle blood pressure over the higher of the two arms’ systolic blood pressures. The ABI measurement was done once in each patient. After obtaining bilateral ABIs, the lower one was used for later analysis. In addition, ABID was calculated as |right ABI–left ABI|.

Collection of demographic and medical data

Age, sex, body mass index (BMI), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and comorbid conditions [13, 14] were acquired from medical records or interviews with study subjects. In addition, patient medications, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, and antiplatelet agents at enrollment, were obtained from medical records. Laboratory data were collected within 1 month of patient enrollment.

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) to perform the statistical analysis. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, percentage, or median (25th–75th percentile) for the follow-up period. Categorical and continuous variables between groups were compared by the chi-square test and independent samples t test, respectively. We input the significant variables from the univariable analysis into the multivariable analysis. The times to all overall and cardiovascular mortality events and the covariates of risk factors were modeled using the Cox proportional hazards model. A Kaplan–Meier survival plot was drawn from baseline to the time of death. The incremental value of ABI-related parameters over conventional parameters to assess the risk for overall and cardiovascular mortality was studied by calculating the improvement in the global chi-square value and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) using STATA 16 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA). To find the optimal cutoff values of ABI and ABID as predictors of overall mortality, we created several models using different cutoff values. The chi-square value was used to select the model with the best performance. All tests were two-sided, and the level of significance was established as P < 0.05.

Results

Among the 941 subjects, mean age was 62 ± 14 years. The prevalence of ABI < 0.9 and ABID ≥ 0.17 was 6.1% (n = 57) and 6.8% (n = 64), respectively. In 64 patients with ABID ≥ 0.17, 46% (n = 31) and 54% (n = 33) of patients had ABI ≥ 0.9 and ABI < 0.9, respectively. Of the 57 patients with ABI < 0.9, 42% (n = 24) and 58% (n = 33) had ABID < 0.17 and ABID ≥ 0.17, respectively. There were 853, 55, and 33 patients with ABI scores of 0, 1, and 2, respectively. Table 1 compares the baseline characteristics according to ABI score. There were significant differences in age, prevalence of diabetes mellitus, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, heart rate, eGFR, percentages of patients taking ACEIs/ARBs, diuretics, and antiplatelet agents, ABI, ABID, prevalence of ABI < 0.9, and prevalence of ABID ≥ 0.17.

The mortality data of the study subjects were collected up to December 2018. Mortality information was acquired from the Collaboration Center of Health Information Application, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Executive Yuan, Taiwan. The median follow-up to mortality was 93 months (25th–75th percentile: 86–101 months). The mortality events recognized during the follow-up period included cardiovascular mortality (n = 87) and overall mortality (n = 228).

Using the chi-square value to select the model with the best performance, the model using ABI < 0.9 and ABID ≥ 0.17 had the best performance in predicting the overall mortality. Table 2 shows the predictors of overall and cardiovascular mortality using the Cox proportional hazards model in the univariable analysis in all 941 study patients. The factors associated with increased overall mortality were increased age, BMI, systolic blood pressure, or heart rate; diuretic use; antiplatelet agent use; diabetes; and decreased cholesterol or eGFR. Of the ABI-related parameters, decreased ABI, increased ABID and ABI score, and the combination of ABI < 0.9 and ABID ≥ 0.17 were associated with increased overall mortality. The factors associated with increased cardiovascular mortality were increased age, BMI, systolic blood pressure, or heart rate; diuretic use; antiplatelet agent use; diabetes; and decreased eGFR. Of the ABI-related parameters, decreased ABI, increased ABID and ABI score, and the combination of ABI < 0.9 and ABID ≥ 0.17 were associated with increased cardiovascular mortality.

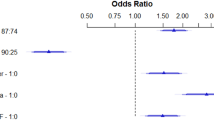

Table 3 shows the predictors of overall and cardiovascular mortality from the Cox proportional hazards model in the multivariable analysis in all 941 study patients. The variables used for the multivariable analysis of overall mortality included age, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, total cholesterol, diabetes, eGFR, BMI, antiplatelet agent use, and diuretic use. The variables used for the multivariable analysis of cardiovascular mortality included age, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, diabetes, eGFR, BMI, antiplatelet agent use, and diuretic use. The multivariable analysis showed that all ABI-related parameters, including ABI, ABID, the combination of ABI < 0.9 and ABID ≥ 0.17, and ABI score, were significantly associated with overall and cardiovascular mortality (P ≤ 0.009).

Figure 1 illustrates the Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival (Fig. 1A) and cardiovascular mortality-free survival (Fig. 1B) in study patients subdivided according to ABI score (both log-rank P < 0.001).

For overall mortality prediction, the univariable model with ABI score (chi-square value, 175.798) outperformed the univariable model with ABI value (chi-square value, 93.823, P < 0.001), ABI < 0.9 (chi-square value, 140.143, P < 0.001), ABID (chi-square value, 101.551, P < 0.001), or ABID ≥ 0.17 (chi-square value, 111.217, P < 0.001). For cardiovascular mortality prediction, the univariable model with ABI score (chi-square value, 97.820) outperformed the univariable model with ABI value (chi-square value, 67.489, P < 0.001), ABI < 0.9 (chi-square value, 87.564, P = 0.001), ABID (chi-square value, 50.247, P < 0.001), or ABID ≥ 0.17 (chi-square value, 54.355, P < 0.001).

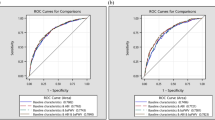

Figures 2 and 3 directly compare ABI-related parameters for overall and cardiovascular mortality prediction in the multivariable model, respectively. The basic model consisted of the significant variables in the univariable analysis except the ABI-related parameters. We added ABI-related parameters to the basic model one by one. Among these models, the basic model + ABI score had the highest predictive value for overall (P ≤ 0.001) and cardiovascular mortality prediction (P ≤ 0.049). We also found that adding ABID ≥ 0.17 to the basic model + ABI < 0.9 provided an extra benefit in the prediction of overall mortality (P < 0.001) and cardiovascular mortality (P = 0.012) when compared with the basic model + ABI < 0.9.

Direct comparison of the basic model + ankle brachial index (ABI), basic model + ABI < 0.9, basic model + ABI difference (ABID), basic model + ABID ≥ 0.17, and basic model + ABI score for overall mortality prediction. The variables in the basic model included the significant variables in the univariable analysis except ABI-related parameters

Direct comparison of the3 basic model + ankle brachial index (ABI), basic model + ABI < 0.9, basic model + ABI difference (ABID), basic model + ABID ≥ 0.17, and basic model + ABI score for cardiovascular mortality prediction. The variables in the basic model included the significant variables in the univariable analysis except ABI-related parameters

When we performed a subgroup analysis in the 872 patients with 0.9 ≤ ABI < 1.3, we found that ABID value and ABID ≥ 0.17 predicted overall mortality, and only ABI value predicted cardiovascular mortality in the multivariable analysis (P ≤ 0.044) (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 4 shows the IDI of ABI parameters (categorical variables) added to the basic model for overall and cardiovascular mortality prediction. As above, the basic model consisted of the significant variables in the univariable analysis except ABI-related parameters. Compared to the basic model alone, adding each ABI parameter (ABI < 0.9, ABID ≥ 0.17, or ABI score) to the basic model provided an extra benefit in the prediction of overall mortality (P ≤ 0.004). Furthermore, adding ABI score and ABI < 0.9 to the basic model also had an extra benefit in the prediction of cardiovascular mortality (P = 0.035 and 0.040, respectively).

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the ABI score (concurrent consideration of ABI < 0.9 and ABID ≥ 0.17) in survival prediction and compared different ABI-related parameters, including ABI, ABID, ABI < 0.9, ABID ≥ 0.17, and ABI score, in the prediction of overall and cardiovascular mortality. We found that the ABI score significantly predicted overall and cardiovascular mortality in the multivariable analysis. In the direct comparison of the univariable models, ABI score was the best a predicting overall and cardiovascular mortality among the five ABI-related parameters (all P < 0.001). In the direct comparison of the multivariable models, the basic model + ABI score was the best model at predicting overall and cardiovascular mortality among the five ABI-related multivariable models (P ≤ 0.049). In addition, in the subgroup analysis of patients with 0.9 ≤ ABI < 1.3, ABID predicted overall mortality in the multivariable analysis.

ABI < 0.9 is a well-established parameter in predicting long-term overall and cardiovascular mortality in different patient groups, including coronary artery disease [15, 16], diabetes [17], chronic kidney disease [3, 18], and hemodialysis [19, 20]. In addition, ABID ≥ 0.15 is reported to be a useful parameter in the prediction of overall mortality in hemodialysis patients, but it might be biased in the prediction of cardiovascular mortality through an effect of peripheral vascular disease [9]. Recently, Han et al. included 2901 patients with acute stroke to examine the ability of ABID to predict short- and long-term outcomes. They found that ABID was associated with poor short-term functional outcomes, the long-term occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality [10]. However, no study has evaluated whether concurrent consideration of low ABI and high ABID is useful in survival prediction. In the present study, we created a novel ABI score by assigning 1 point for ABI < 0.9 and 1 point for ABID ≥ 0.17 and found that the ABI score not only was a useful parameter in the prediction of long-term overall and cardiovascular mortality but also had the best predictive value for overall and cardiovascular mortality among the five ABI-related parameters in both the univariable and multivariable models. Of our 64 study subjects with ABID ≥ 0.17, there were 31 patients (46%) without ABI < 0.9. Because ABID ≥ 0.17 was a helpful parameter in survival prediction, only considering ABI < 0.9 might not yield good mortality predictions. On the other hand, of the 57 patients with ABI < 0.9, 42% (n = 24) did not have ABID ≥ 0.17. As above, because ABI < 0.9 was a helpful parameter in survival prediction, only considering ABI ≥ 0.17 might not yield good mortality predictions. We reasoned that an ABI score that takes ABI < 0.9 and ABID ≥ 0.17 into consideration concurrently should be able to exert good value in survival prediction. In fact, compared to the other ABI-related parameters, including ABI, ABID, ABI < 0.9, and ABID ≥ 0.17, the ABI score had the best value for long-term overall and cardiovascular mortality prediction in our study subjects.

Low ABI and high ABID have been associated with the presence of peripheral artery disease (PAD) [21]. However, low ABI was reported to be not sensitive enough to detect asymptomatic PAD in the general population [22]. Recently, a high normal ABI was reported to be associated with renal artery intimal thickening and impaired renal function in chronic kidney disease [23]. Hence, some patients with PAD might not be detected by ABI < 0.9. Because increased ABID is associated with the presence of PAD, ABID might be a useful parameter in the detection of PAD in patients with normal ABI [10, 11]. Therefore, ABI score, concurrently considering ABI < 0.9 and ABID ≥ 0.17, might have the potential to detect more patients with PAD than ABI < 0.9 or ABID ≥ 0.17 alone. Patients with higher ABI scores might have a higher percentage of PAD and concomitant atherosclerosis and thus might have a higher mortality.

Recently, high ABID was found to be associated with increased all-cause mortality in patients with acute ischemic stroke without PAD indicated by ABI ≥ 0.9 [10]. Consistent with that finding, we found that increased ABID was a useful predictor of overall mortality in patients with 0.9 ≤ ABI < 1.3 on multivariable analysis. In addition, in the study of Lin et al. including chronic hemodialysis patients, ABID ≥ 0.15 was not associated with increased mortality in patients with ABI ≥ 0.9 [9]. Our present study similarly found that ABID ≥ 0.17 could not predict mortality in patients with 0.9 ≤ ABI < 1.3 in the multivariable analysis.

Study limitations

There were several limitations to this study. First, our study patients were enrolled from those scheduled for echocardiographic examination, so their baseline characteristics were very heterogeneous. Therefore, our results must be cautiously interpreted when applied to a homogeneous study group, such as chronic kidney disease, diabetes, hypertension, chronic heart failure, and generally healthy patients. Second, information on LDL-C, HDL-C, smoking history, and medications for diabetes and dyslipidemia was lacking, so we could not analyze the impact of such parameters on mortality. Third, we only aimed to evaluate the mortality events, so nonfatal events were not studied. Fourth, because there has been no large-scale study to validate the optimal cutoff value of ABID, we used the chi-square value to select the best cutoff value of ABID in predicting overall mortality. The best cutoff value of ABID in mortality prediction in might be different in different study populations. Fifth, surgery might have affected the patients’ prognosis. Three patients underwent amputation of the leg and were excluded from the study, but we had no the other operation data. Sixth, there might be a selection bias because we excluded patients who could not begin the ABI measurement within 10 min after the completion of the echocardiographic examination. Seventh, patients with insignificant valvular heart diseases, ischemic heart diseases, and dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy were not excluded from our cohort, which might have affected the outcome prediction. Finally, although ABI < 0.9 and ABID ≥ 0.17 make different contributions to mortality prediction, we arbitrarily assigned one point for ABI < 0.9 and one point for ABID ≥ 0.17 when calculating the ABI score. It should be noted that the hazard ratios of ABI < 0.9 (5.926) and ABID ≥ 0.17 (5.033) in predicting overall mortality were similar.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that the ABI score could significantly predict overall and cardiovascular mortality on multivariable analysis. Furthermore, when we directly compared the univariable models, the model with the ABI score was the best at predicting overall and cardiovascular mortality among the five ABI-related parameters. In the direct comparison of the 5 multivariable models, the basic model +ABI score was the best at predicting overall and cardiovascular mortality. Hence, the ABI score, a combination of ABI < 0.9 and ABID ≥ 0.17, should be calculated for better mortality prediction.

References

Crawford F, Welch K, Andras A, Chappell FM. Ankle brachial index for the diagnosis of lower limb peripheral arterial disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:Cd010680.

Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Redmond N, Lin JS. Screening for peripheral artery disease using the ankle-brachial index: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:184–96.

Chen HY, Wei F, Wang LH, Wang Z, Meng J, Yu HB, et al. Abnormal ankle-brachial index and risk of cardiovascular or all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: a meta-analysis. J Nephrol. 2017;30:493–501.

Chen SC, Huang JC, Su HM, Chiu YW, Chang JM, Hwang SJ, et al. Prognostic cardiovascular markers in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2018;43:1388–407.

Chen SC, Chang JM, Hwang SJ, Tsai JC, Liu WC, Wang CS, et al. Ankle brachial index as a predictor for mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease and undergoing haemodialysis. Nephrology. 2010;15:294–9.

Nakahashi T, Tada H, Sakata K, Yakuta Y, Tanaka Y, Gamou T, et al. Impact of decreased ankle-brachial index on 30-day bleeding complications and long-term mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Cardiol. 2019;74:116–22.

Samba H, Guerchet M, Ndamba-Bandzouzi B, Kehoua G, Mbelesso P, Desormais I, et al. Ankle Brachial Index (ABI) predicts 2-year mortality risk among older adults in the Republic of Congo: The EPIDEMCA-FU study. Atherosclerosis. 2019;286:121–7.

Yamawaki M, Araki M, Ito T, Honda Y, Tokuda T, Ito Y, et al. Ankle-brachial pressure index as a predictor of the 2-year outcome after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: data from the Japanese OCEAN-TAVI Registry. Heart Vessels. 2018;33:640–50.

Lin CY, Leu JG, Fang YW, Tsai MH. Association of interleg difference of ankle brachial index with overall and cardiovascular mortality in chronic hemodialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2015;37:88–95.

Han M, Kim YD, Choi JK, Choi J, Ha J, Park E, et al. Predicting stroke outcomes using ankle-brachial index and inter-ankle blood pressure difference. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1125.

Cheng YB, Li Y, Sheng CS, Huang QF, Wang JG. Quantification of the interrelationship between brachial-ankle and carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity in a workplace population. Pulse. 2016;3:253–62.

Hsu PC, Lee WH, Chen YC, Lee MK, Tsai WC, Chu CY, et al. Comparison of different ankle-brachial indices in the prediction of overall and cardiovascular mortality. Atherosclerosis. 2020;304:57–63.

Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:S81–S90.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72.

Liu L, Sun H, Nie F, Hu X. Prognostic value of abnormal ankle-brachial index in patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Angiology. 2020;71:491–7.

Sasaki M, Mitsutake Y, Ueno T, Fukami A, Sasaki KI, Yokoyama S, et al. Low ankle brachial index predicts poor outcomes including target lesion revascularization during the long-term follow up after drug-eluting stent implantation for coronary artery disease. J Cardiol. 2020;75:250–4.

Ena J, Pérez-Martín S, Argente CR, Lozano T. Association between an elevated inter-arm systolic blood pressure difference, the ankle-brachial index, and mortality in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Invest Arterioscler. 2020;32:94–100.

Nishimura H, Miura T, Minamisawa M, Ueki Y, Abe N, Hashizume N, et al. Ankle-brachial index for the prognosis of cardiovascular disease in patients with mild renal insufficiency. Intern Med. 2017;56:2103–11.

Miguel JB, Matos JPS, Lugon JR. Ankle-Brachial index as a predictor of mortality in hemodialysis: a 5-year cohort study. Arquivos Bras Cardiol. 2017;108:204–11.

Adragao T, Pires A, Branco P, Castro R, Oliveira A, Nogueira C, et al. Ankle-brachial index, vascular calcifications and mortality in dialysis patients. Nephrol, Dialysis, Transplant. 2012;27:318–25.

Herráiz-Adillo Á, Soriano-Cano A, Martínez-Hortelano JA, Garrido-Miguel M, Mariana-Herráiz J, Martínez-Vizcaíno V, et al. Simultaneous inter-arm and inter-leg systolic blood pressure differences to diagnose peripheral artery disease: a diagnostic accuracy study. Blood Press. 2018;27:121–2.

Zhang Z, Ma J, Tao X, Zhou Y, Liu X, Su H. The prevalence and influence factors of inter-ankle systolic blood pressure difference in community population. PloS ONE. 2013;8:e70777.

Zamami R, Ishida A, Miyagi T, Yamazato M, Kohagura K, Ohya Y. A high normal ankle-brachial index is associated with biopsy-proven severe renal small artery intimal thickening and impaired renal function in chronic kidney disease. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:929–37.

Acknowledgements

Mortality data were provided by the Collaboration Center of Health Information Application, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Executive Yuan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tsai, WC., Lee, WH., Chen, YC. et al. Combination of low ankle-brachial index and high ankle-brachial index difference for mortality prediction. Hypertens Res 44, 850–857 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00636-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00636-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Current topic of vascular function in hypertension

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Update on Hypertension Research in 2021

Hypertension Research (2022)