Abstract

Preeclampsia is a multisystem, multiorgan hypertensive disorder of pregnancy responsible for maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality in low- and middle-income countries. The classic diagnostic features hold less specificity for preeclampsia and its associated adverse outcomes, suggesting a need for specific and reliable biomarkers for the early prediction of preeclampsia. The imbalance of pro- and antiangiogenic circulatory factors contributes to the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Several studies have examined the profile of angiogenic factors in preeclampsia to search for a biomarker that will improve the diagnostic ability of preeclampsia and associated adverse outcomes. This may help in more efficient patient management and the reduction of associated health care costs. This article reviews the findings from previous studies published to date on angiogenic factors and suggests a need to apply a multivariable model from the beginning of pregnancy and continuing throughout gestation for the early and specific prediction of preeclampsia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preeclampsia (PE) is a multisystem hypertensive disorder of pregnancy [1] and complicates 2–8% of pregnancies around the world [2]. It is a significant contributor to maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality globally [3], especially in low-to-middle-income countries [4]. Data from the National Eclampsia Registry indicate the incidence of hypertensive disorders to be 10.08% in India [5]. PE is characterized as the development of hypertension past 20 weeks of gestation along with one or more of the following conditions: proteinuria, fetal growth restriction or dysfunction in maternal organs (including complications in the kidney, liver and blood) [6,7,8]. PE, if left unattended, can lead to adverse complications such as seizures (eclampsia), HELLP (hemolysis elevated liver enzymes and low platelets) syndrome, fetal growth restriction and abruptio placentae [9].

The clinical features have a low sensitivity and specificity for the prediction of PE progression as well as maternal and perinatal outcomes [4]. This leads to unnecessary hospitalization, monitoring and repeated assessments of patients who might not develop PE (false positive) or PE-associated adverse outcomes in the future, while some cases may be missed [10]. Thus, there is a need for reliable biomarkers to predict the risk of PE development and associated complications for improved patient management and reduction in health care costs [1].

PE is known to be associated with altered angiogenesis, which involves an imbalance of pro- and antiangiogenic circulatory factors [11]. Angiogenesis is the formation of new blood vessels from the prevailing vasculature [12] via proangiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), placental growth factor (PlGF) and their membrane-bound receptors: kinase domain receptor (KDR) and fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (Flt-1) receptor. The placenta secretes two antiangiogenic factors, namely, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) and soluble endoglin (sEndoglin), into the maternal circulation. Increased levels of these factors have been suggested to be associated with the clinical manifestation of PE [13]. Studies have been undertaken to analyze the profiles of different angiogenic factors along with standard diagnostic criteria as predictors of PE.

The aim of this article is to summarize the findings from previous studies published to date on the role of angiogenic factors as having the potential to be used as biomarkers for the prediction of PE. This review was written by referring to the PubMed database using the following keywords: PE [Title] AND Angiogenic Factors (VEGF, PlGF, sEndoglin and sFlt-1) [Title/Abstract] AND cross-sectional studies AND longitudinal studies. The search was limited due to the selection of articles published in the English language.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

VEGF is the principal proangiogenic factor. The VEGF family includes seven members with a VEGF homology domain in common [14]: VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, VEGF-E, VEGF-F, and PlGF. Endothelial, stromal and hematopoietic cells are the main sources of VEGF, which is produced during hypoxic conditions as well as upon stimulation by mediators such as interleukins, transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and platelet-derived growth factors [15]. There are three kinds of receptors for mammalian VEGF: fms-like tyrosine kinase Flt-1 (VEGFR1/Flt-1), the KDR or fetal liver kinase (VEGFR2/Flk-1) and Flt-4 (VEGFR-3). VEGF-A, VEGF-B and PlGF bind to Flt-1; among the VEGF family members, only VEGF-A binds to Flt-1. Flt-4/VEGFR-3 is restricted mainly to the lymphatic endothelium and binds with VEGF-C and VEGF-D [16]. VEGFR-2 seems to be the most potent receptor through which VEGF mediates its actions. VEGFR-1, upon stimulation with VEGF, cannot generate a mitogenic response and has very weak kinase activity [17]. The proangiogenic functions of VEGF include induction of endothelial proliferation and vascular permeability in endothelial cells involved in angiogenic invasion [18] and maintenance of endothelial cell function [19] (Fig. 1A).

Binding of angiogenic factors in normal pregnancy. A VEGFR-1 upon stimulation with VEGF cannot generate a mitogenic response. VEGFR-2 is the most potent receptor through which VEGF mediates its actions. Flt-4/VEGFR-3 is restricted mainly to the lymphatic endothelium. B PlGF, upon binding to Flt-1, displaces VEGF and redirects it to bind to its potent but low-affinity receptor VEGFR-2/KDR and promotes angiogenesis. C Endoglin/CD 105 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that functions as a coreceptor for TGF-β1 and TGF-β3. Endoglin is also required for the activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), which produces NO, a potent vasodilator. The proper balance and binding of angiogenic factors leads to proper remodeling of spiral arteries, thereby providing a sufficient supply of blood and oxygen to the developing placenta

Placental growth factor (PlGF)

PlGF is another important proangiogenic factor belonging to the VEGF family. It is produced by placental trophoblast cells [4]. Along with recruitment of smooth muscle cells, macrophages and pericytes, which assist angiogenesis, PlGF stimulates endothelial cell migration [2]. Upon binding to Flt-1, PlGF displaces VEGF and redirects it to bind to its potent but low-affinity receptor VEGFR-2/KDR [20]. In this way, even though PlGF alone does not mediate vascular permeability, it strengthens VEGF signaling and promotes angiogenesis [15] (Fig. 1B). Binding of PlGF to Flt-1 is considered proangiogenic, as it enhances the bioavailability of VEGF to bind to a more proangiogenic KDR, whereas VEGF binding to Flt-1 is considered slightly antiangiogenic due to its weak kinase activity [21]. A constant increase in PlGF (total PlGF) occurs during the first two trimesters in a normal pregnancy, peaking at ~29–32 weeks and then declining steadily due to a rise in the levels of the antiangiogenic factor sFlt-1 that binds with free PlGF [22].

Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1)

Flt-1 or VEGFR-1 protein is a transmembrane receptor made up of three key domains: a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain, a transmembrane domain and an extracellular ligand binding domain [23]. Hypoxic conditions upregulate the Flt-1 gene in trophoblastic cells [24]. Both sFlt-1 and Flt-1 are transcribed from the Flt-1 gene [25]. sFlt-1 is a splice variant of Flt-1 lacking both transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of membrane-bound Flt-1 [18]. sFlt-1 has multiple splice variants [26]. These variants occupy different tissue locations, indicating potentially different pathological and physiological roles. sFlt-1 i13 (also known as sFlt-1-1 or sFlt-1 v1) is the main variant in humans and is expressed widely in most tissues. sFlt-1 e15a (also known as sFlt-1 14 or sFlt-1 v2) is present only in humans and higher-order primates [3]. This variant is secreted mainly from the placenta and is shown to be elevated significantly in the maternal circulation and placentas of women with PE [27], leading to endothelial dysfunction [28].

Soluble endoglin (sEndoglin)

Endoglin/CD 105 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that functions as a coreceptor for transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) and transforming growth factor beta 3 (TGF-β3), which are involved in the proliferation and differentiation of trophoblast cells [15]. The receptor consists of three chief domains: a cytoplasmic domain, a transmembrane domain and an extracellular domain [29]. Syncytiotrophoblast cells and vascular endothelial cells exhibit higher expression of this receptor [30]. Endoglin is also required for the activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, which produces NO (nitric oxide), a potent vasodilator [2] (Fig. 1C).

Soluble endoglin (sEndoglin) is a truncated variant of the extracellular domain of receptor endoglin and is released from syncytiotrophoblasts [31]. This soluble form of endoglin antagonizes the actions of endoglin by binding to TGF-β1, which further inhibits its binding to the receptor [32]. This prevents vasodilation via downregulation of nitric oxide synthase [15], leading to a reduction in the levels of vasodilator NO. Endoglin also promotes autophagy of syncytiotrophoblasts, which is necessary for normal placentation. The process of autophagy is prevented by sEndoglin, resulting in poor trophoblast invasion and uterine artery remodeling [33] (Fig. 2A).

Binding of angiogenic factors in preeclamptic pregnancy. A The soluble form of endoglin antagonizes the action of endoglin by binding to TGF-β1, which further inhibits its binding to the receptor. This prevents vasodilation via downregulation of nitric oxide synthase, leading to a reduction in the levels of vasodilator NO. B Even though increased levels of VEGF are secreted during hypoxia, the expression of the soluble form of Flt-1 increases to a greater extent in PE, which binds to free VEGF and PlGF, rendering them unavailable for binding with their cell membrane-bound receptors, leading to altered angiogenesis at the placental level in preeclampsia

Angiogenesis in pregnancy

In most mammalian species, zygotes develop upon fertilization of an egg by sperm. This fertilization occurs in the fallopian tube. Upon successful fertilization, the zygote (fertilized egg) travels down the fallopian tube toward the uterus, during which it divides and develops into a multicellular structure called a blastocyst [34]. On approximately the 5th day of conception, blastocyst differentiation occurs, resulting in the inner cell mass and outer trophoblast cell layer [22]. The gestational sac is present in a reduced-oxygen-tension environment in the early phases of implantation. This environment promotes trophoblast proliferation. These proliferating trophoblasts plug the tips of spiral arteries within the maternal decidua, creating an initial hypoxic environment by blocking the blood supply from spiral arteries [35].

These initial hypoxic conditions promote the expression of VEGF in trophoblastic cells. As the expression of proangiogenic VEGF is enhanced, hypoxia promotes the expression of the Flt-1 gene, which produces Flt-1 (transmembrane form) and soluble Flt-1 (free form). This sFlt-1 helps in maintaining VEGF levels [21]. In addition, transcription factors hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha and 2 alpha (HIF1α and 2α) are markers of cellular oxygen deprivation and are found to be expressed initially under hypoxic conditions [36]. Eventually, the intervillous space develops after the collapse of trophoblastic-spiral artery plugs through which maternal blood enters, thereby increasing oxygen tension [37]. The cytotrophoblast cell phenotype changes from an epithelial cell phenotype to an endothelial cell phenotype [29], gradually transforming the spiral arteries into low pressure, low resistance and high capacitance dilated sacs [38]. This process leads to an enhanced blood and thereby oxygen supply to the developing placenta and resolves the initial hypoxic conditions. These events lead to healthy, normal pregnancy, in which the levels of antiangiogenic sFlt-1 are low in maternal blood until the second trimester and rise only after 33–36 gestational weeks, parallel to decrease in the proangiogenic factors VEGF and PlGF [39] (Fig. 3).

Role of angiogenic factors in the development of preeclampsia

In PE, cytotrophoblast cells fail to transform into the invasive endothelial subtype, which leads to incomplete spiral artery remodeling, leading to an inefficient provision of the blood and oxygen supply to the developing placenta, resulting in prolonged hypoxic conditions [35]. Although increased levels of VEGF are secreted during hypoxia, the expression of the soluble form of Flt-1 increases to a greater extent in PE. This disrupts the balance between pro- and antiangiogenic factors that is achieved during normal pregnancies [21] (Fig. 4). The soluble form of Flt-1 binds to free VEGF and PlGF, rendering them unavailable for binding with their cell membrane-bound receptors (Flt-1 for VEGF and PlGF, KDR for VEGF) [15] (Fig. 2B). Such a vast increase in the antiangiogenic state in maternal blood causes systemic vascular dysfunction by different mechanisms and leads to PE-associated maternal symptoms (Fig. 4).

Studies examining angiogenic factors in preeclampsia

Over the last few decades, our understanding regarding the pathophysiology of PE has seen major advances. Alterations in placental angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors have been the key discoveries to understand the molecular basis of PE pathology. However, the placenta is available only after delivery, and hence, examining angiogenic factors from maternal blood which is available throughout gestation will help in the early prediction of PE and its associated adverse outcomes. The next sections describe studies that have examined the role of angiogenic factors in the development of PE.

Cross-sectional studies

VEGF

Reports on the levels of free VEGF in women with PE are inconclusive. Some studies report lower plasma/serum concentrations of free VEGF in women with PE at the end of pregnancy [40,41,42]. In contrast, other studies have shown higher maternal serum levels of free VEGF in women with PE [43,44,45,46,47]. Lee et al. reported higher serum total VEGF and lower free VEGF levels in women with PE [48]. Our earlier cross-sectional study by Kulkarni et al. also reported lower plasma free VEGF levels at delivery in 58 women with PE than in 59 normotensive women [49]. The abovementioned studies were undertaken with a small sample size and at the end of pregnancy.

PlGF

Lower levels of serum/plasma PlGF have been reported at the end of pregnancy in women with PE compared to controls [41, 49,50,51]. Similarly, lower levels of PlGF have been reported at 24–26 weeks of gestation in women with PE [52]. Higher maternal levels of PlGF at 10–14 weeks of gestation have been shown to be associated with a reduced risk of PE [53]. Low PlGF levels at <34 weeks of gestation have also been reported in women with PE [54]. Very low levels of PlGF (<12 pg/ml) between 19 and 35 weeks of gestation were found to be associated with a higher emergency cesarean section rate and early delivery in women at risk of PE [55]. A prospective noninterventional, multicenter study, performed by O’Gorman, included 8775 singleton pregnancies at 11–13 weeks of gestation. The study reported that an algorithm combining “PlGF levels with maternal clinical factors, Uterine Artery Pulsatility Index (UtA-PI) and mean arterial pressure (MAP)” to screen for PE (n = 239) at 11–13 weeks of gestation was far superior to the conventional use of maternal clinical risk factors for PE screening [56]. Poon et al. applied an algorithm incorporating “MAP, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A, logs of UtA-PI, body mass index, presence of previous PE or nulliparity and serum free PlGF levels” and reported detection rates of a 93% for early-onset PE (n = 34) and 36% for late-onset PE (n = 123) [57].

In contrast to the abovementioned studies, Litwińska et al. found that the measurement of PlGF at 11–13 weeks of gestation was not useful, as the rates of detection for early- and late-onset PE with PlGF alone were 57% and 34%, respectively. A model including maternal risk factors, mean UtA-PI and MAP was useful in the prediction of late-onset PE (n = 29) (85% sensitivity and 83% specificity). In the case of early-onset PE (n = 22), a model including maternal risk factors, UtA-PI and PlGF levels had 91% sensitivity and 84% specificity, but the study was conducted on a small sample size [58]. The results of the PARROT trial, a multicentric randomized control trial involving 11 maternity units of the UK, suggest that adapting PlGF testing as a diagnostic adjunct should be considered in women with suspected PE [59].

sFlt-1

High plasma levels of sFlt-1 at delivery have been reported in women with PE [41, 42, 48, 49, 51]. In the plasma of women with early- and late-onset PE, levels of sFlt-1 were higher than those in gestational matched controls [60]. Chaiworapongsa et al. also reported higher sFlt-1 levels from 26 to 41 gestational weeks in women with PE than in controls and particularly higher sFlt-1 levels in early-onset PE than in late-onset PE patients [61]. In contrast, sFlt-1 has been suggested to be a valuable marker for the detection of late-onset PE [62]. Studies also report comparable sFlt-1 levels between women with PE and controls [52, 53]. A nested, case-control study by Smith et al. indicates that higher maternal levels of PlGF at 10–14 weeks of gestation are associated with a reduced risk of PE, whereas higher maternal sFlt-1 levels are not associated with a risk of PE [53]. The study by Furuya et al. in an advanced maternal age (AMA) mouse model demonstrated lower levels of serum PlGF and sFlt-1 at late gestation than those in control mice. The study also showed the occurrence of the same phenomenon for the serum sFlt-1 profile in human AMA complicated by hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP). Serum samples were obtained from aged (over 40 years) and young (under 30 years) HDP patients. Based on the findings, the study concludes that serum sFlt-1 levels do not always reflect the conventional pathogenesis of HDP in aged murine and human pregnancies but can contribute to the future management of HDP in AMA [63].

Longitudinal studies

In a study by Levine et al., concentrations of free VEGF, PlGF and total sFlt-1 were calculated from serum samples collected across gestation. VEGF levels were found to be low throughout pregnancy, and the authors suggest that VEGF was not a significant predictor of PE. In the same study, an increase in sFlt-1 concentration with an accompanying decrease in free PlGF was observed in women who later developed PE [64]. The same group later demonstrated that maternal serum levels of sEndoglin were increased at 2–3 months before the onset of clinical disease and further increased as gestation progressed [65]. Reduced concentrations of proangiogenic factors (VEGF and PlGF) along with elevated levels of antiangiogenic factors (sFlt-1 and the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio) have been demonstrated by one of our departmental studies in women with PE (n = 35) during early gestation [66].

A study by Rana et al. demonstrated significantly elevated levels of sFlt-1 by 17–20 weeks of gestation in women who would go on to develop PE (n = 39) in the future compared with healthy controls (n = 147). The study proposed that changes in sFlt-1 during the first and second trimesters may be potentially useful for screening patients at high risk of developing preterm PE [67]. Hertig et al. demonstrated a significant increase in the concentration of sFlt-1 in maternal serum at ~6.5 weeks before the onset of hypertension and proteinuria in 23 pregnant women who went on to develop PE in the future [68]. Palmer et al. have shown that sFlt-1 levels gradually rise with advancing gestation and are significantly elevated in women who develop PE later, especially early-onset PE [28]. Romero et al. demonstrated that alterations in maternal angiogenic factors (PlGF, sFlt-1 and sEndoglin) occur prior to the clinical presentation of PE [69].

A longitudinal study on 50 women with PE and 250 controls indicated that maternal plasma PlGF levels remained similar in controls and women with PE between 4 and 15 weeks of gestation. However, the PlGF levels were lower between 15.1 and 25 weeks of gestation and lowered further from 25.1 weeks of gestation until delivery in women with PE. On the other hand, maternal plasma sFlt-1 levels were similar between the groups from 4 to 15 weeks and from 15 to 25 weeks of gestation. The levels increased in women with PE only after 25.1 weeks of gestation until delivery [51]. A study by Krauss et al. on 117 women who developed PE demonstrated that plasma PlGF levels in the second half of pregnancy are not useful in the prediction of PE [70]. In a longitudinal nested case-control study on 28 women with PE, maternal PlGF was reduced at 17, 25 and 33 weeks of gestation compared with controls, indicating that a reduction in PlGF levels right from the 17th week of gestation is useful in the prediction of PE [71].

A study of 201 normal and 56 PE pregnancies by Erez et al. demonstrated that, the ratio [PlGF/(sEndoglin × sFlt-1)] was useful in determining the risk of preterm PE [72]. In another longitudinal study by Kusanovic et al. on 62 women with PE, individual angiogenic (PlGF) and antiangiogenic factors (sFlt-1 and sEndoglin) measured at early pregnancy (6–15 weeks) and in the mid trimester (20–25 weeks) had a low predictive ability for PE. However, the best predictive performance was shown by a combination of analytes, such as the PlGF/sEndoglin ratio, with 100% sensitivity and 98–99% specificity [73]. Perni et al. carried out a longitudinal study on superimposed PE to investigate the levels of angiogenic factors in pregnant women with chronic hypertension (n = 109) who later developed superimposed PE (n = 37, of which 9 cases were early-onset and 28 were late-onset PE) at the 12th, 20th, 28th and 36th weeks of gestation and 6 weeks after childbirth. Compared to uncomplicated pregnancies with chronic hypertension, the pregnancies with superimposed early- or late-onset PE showed significantly higher levels of circulating sFlt-1 and sEndoglin and a higher sFlt-1/PlGF ratio, along with significantly lower levels of PlGF before clinical diagnosis (in cases of early-onset superimposed PE) and at the time of diagnosis (in cases of early- and late-onset superimposed PE) [74].

A longitudinal case-control study enrolled 12 singleton pregnancies that developed PE and 104 singleton normal pregnancies, of which 14 gave birth to small-for-gestational-age (SGA) infants. Significantly lower levels of PlGF were observed in preeclamptic pregnancies in the second (20–26 weeks) and third trimesters (28–35 weeks of gestation), with significantly higher levels of sFlt-1 only in the third trimester compared to normotensive controls. The sFlt-1/PlGF ratio was also significantly higher in the PE group in both the second and third trimesters than in normal pregnancies. A logistic regression model including Doppler PI measures from the second trimester and the relative difference in PlGF from the first to second trimesters along with BMI provided a specificity of 99% and sensitivity of 46% for the prediction of PE, with a negative predictive value (NPV) of 98.3%, indicating that these parameters are considerable markers for PE [75].

Myatt et al., in a longitudinal nested case-control study, enrolled 468 normotensive nonproteinuric control women and 158 women with PE and collected blood samples at 9–12, 15–18 and 23–26 weeks of gestation. Significant differences in the rates of change in PlGF, sFlt-1 and sEndoglin were observed between the first and either early or late second trimesters in women who developed PE and in those with severe or early-onset PE compared to controls. Inclusion of clinical characteristics (race, BMI and blood pressure) enhanced the sensitivity for the detection of severe and particularly early-onset PE. The sensitivities of PlGF, sFlt-1 and sEndoglin together with clinical characteristics in the prediction of early-onset PE were 77%, 77% and 88%, respectively, with a specificity of 80%. [76]. In a longitudinal nested case-control study, Khalil et al. showed significantly elevated levels of sEndoglin beginning at 18 weeks of gestation and a further increase in sEndoglin levels with gestational age in the preterm PE group (n = 12, delivery <37 weeks) compared with the control group (n = 85). In women with gestational hypertension (GH) (n = 12) and term PE (n = 13), the levels of sEndoglin did not differ significantly from those of the control group. From these observations, the study concluded that during screening for PE, measurement of plasma sEndoglin levels during the second and third trimesters may improve the predictive accuracy for PE and reduce the false-positive rate [77].

A prospective longitudinal study by Khalil in 2016 showed significantly higher levels of sFlt-1 from 15 weeks gestation onwards and significantly lower levels of PlGF from 11 weeks onwards in the preterm PE group (n = 22, delivery <37 weeks) than normotensive controls (n = 172), and the difference for both parameters increased significantly with gestational age. Similar results were obtained for the term PE (n = 22) and gestational hypertension (GH) groups (n = 18), where PlGF levels were lower beginning at 13 (in the PE group) and 27 weeks (in the GH group), and the difference increased significantly with gestational age. The sFlt-1/PlGF ratio was significantly higher in the preterm PE group from 11 weeks onwards than in the control group, and the difference increased significantly with gestational age. From all the observations, the study concluded that repeated measurements of biochemical markers may provide better PE prediction than measurements at a single time point during pregnancy, as other pregnancy complications also show similar trends in angiogenic markers at late gestational time points. The study also concluded that during screening for preterm PE, maternal serum PlGF is a valuable marker from the first trimester onwards, while sFlt-1 levels are likely to have a predictive ability from the second trimester onwards. Regarding term PE, the study concluded that serum PlGF levels are reduced from the first trimester onwards, while sFlt-1 levels have a lower chance of being useful for prediction [78].

Erez et al. conducted a longitudinal study throughout gestation in 76 women with late-onset PE (diagnosis at ≥34 weeks of gestation) and 90 control subjects. Multimarker prediction models have been designed using data from one of the five gestational age intervals (8–16, 16.1–22, 22.1–28, 28.1–32, 32.1–36 weeks of gestation). PlGF was the best predictor for LOPE (late-onset PE) after 22 weeks of gestation, identifying 1/3–1/2 of patients destined to develop the disorder at 20% FPR. The study concluded that elevated MMP-7 (matrix metalloproteinase-7) early in gestation (8–22 weeks) and reduced PlGF later in gestation (after 22 weeks) are the strongest predictors of subsequent development of LOPE [79].

Jääskeläinen et al. performed a longitudinal study to determine the levels of PlGF, sFlt-1 and sEndoglin in the first and second/third trimesters of pregnancy in a FINNPEC case-control cohort. Blood samples were collected in the first trimester (9–15 weeks of gestation) from 221 women who later developed PE and 239 women who did not develop PE. Second/third-trimester blood samples (20–42 weeks of gestation) were obtained from 175 women with PE and 55 without PE. An increase in the serum concentration of sFlt-1 was found only in the second/third trimester in women with PE. Higher sFlt-1 levels, sEndoglin levels and sFlt-1/PlGF ratios were found in the third trimester in primiparous women than in multiparous women. A lower concentration of PlGF was also found in primiparous women in the third trimester. These observations suggest that primiparous women have a more antiangiogenic profile during the second/third trimester than multiparous pregnant women [80].

sFlt-1 to PlGF ratio

PlGF and sFlt-1 have an inverse relationship with each other, and it has been suggested that their ratio (sFlt-1/PlGF) can be a better predictor for PE than either factor alone. Several studies have evaluated the potential of the ratio to predict PE and its adverse outcomes.

Several cross-sectional studies have demonstrated a higher sFlt-1/PlGF ratio at different gestational time points in women with PE. Women enrolled with no PE symptoms at 26 weeks of gestation who later developed PE (n = 12) were reported to have lower maternal plasma PlGF and higher maternal plasma sFlt-1 levels than normotensive controls (n = 59), suggesting that the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio could be an efficient biomarker for PE prediction [81, 82]. A comparison between early- (n = 20, delivery <34 weeks) and late-onset PE patients (n = 24, delivery ≥34 weeks) indicated higher maternal serum sFlt-1 and sFlt-1/PlGF ratios along with lower maternal PlGF levels in early-onset PE patients [83].

A cross-sectional case-control study including women recruited between 26 and 41 weeks of gestation reported higher sFlt-1 and sFlt-1/PlGF ratios along with lower levels of PlGF in women with PE than in women with normal pregnancy [84]. Similarly, higher sFlt-1/PlGF ratios were observed in a cross-sectional study in 44 Nepalese women who developed PE, with significantly higher levels in those women who developed pregnancy complications along with PE [85]. A multicenter case-control cross-sectional study that included 71 PE- and 280 gestational age-matched controls demonstrated area under the receiver operator characteristic curve (AOC) values of 0.95 for the sFlt-1 to PlGF ratio, 0.92 for PlGF, and 0.91 for sFlt-1, indicating that the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio has better predictive ability than sFlt-1 or PlGF alone. The best performance of the ratio was obtained for the determination of early-onset PE, with an AOC of 0.97 [86].

The possible use of the ratio to discriminate between women who develop PE and women who develop other pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders after 24 weeks of gestation was demonstrated by Verlohren et al. in a cross-sectional study [87]. Another cross-sectional study provided cutoff values for the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio in 234 women with PE at the time of PE diagnosis (≥20 weeks of gestation) for clinical application in PE diagnosis. Ratio cutoffs ≤33 and ≥85 showed a sensitivity/specificity of 95%/94% and 88%/99.5%, respectively, between 20 and 34 weeks of gestation. After 34 weeks, cutoffs of ≤33 and ≥110 provided a sensitivity/specificity of 89.6%/73% and 58.2%/95.5%, respectively [88].

Rana et al. applied the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio to classify women with PE into groups of women with angiogenic PE (n = 51) (having a sFlt-1/PlGF ratio > 85) and women with nonangiogenic PE (n = 46) (having a sFlt-1/PlGF ratio <85), based on the levels of angiogenic factors (sFlt-1 and PlGF). Women with nonangiogenic PE had no adverse outcomes, whereas women with angiogenic PE developed abruption, elevated liver function tests, pulmonary edema, low platelet counts, eclampsia, and SGA babies. Nonangiogenic PE had a preterm delivery rate (delivery <34 weeks of gestation) of 8.7%, in contrast to a rate of 64.7% for angiogenic PE. This indicates better performance of the ratio in the prediction of severe outcomes associated with PE than conventional blood pressure and proteinuria measurements [89]. Similar results were obtained in a cross-sectional study assessing the severity of gestational hypertension and PE [90].

A large longitudinal PROGNOSIS (Prediction of Short-term Outcomes in Pregnant Women with Suspected PE) study was conducted between 24 and 36 weeks of gestation in pregnant women with suspected PE (n = 1273). The aim of the study was to determine whether low ratios can rule out the development of PE along with related complications in the following week and whether high ratios can rule in the development of PE and complications in the following 4 weeks. A sFlt-1/PlGF ratio of 38 or smaller could rule out PE in the following week along with a NPV of 99.3%, sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 78.3%. A high NPV indicates a very low chance of PE development in a woman. Women with a ratio above 38 might develop PE within the following 4 weeks (positive predictive value of 36.7%, sensitivity of 66.2% and specificity 83.1%) [91, 92]. A review article mentioned the limitation of the PROGNOSIS study, namely, that the population was a high-risk singleton pregnancy population; therefore, these results cannot be applied to the general pregnancy population, twin pregnancies and women outside the 24–37-week timeframe, suggesting the need for an appropriate cutoff value for disease diagnosis in specific situations [10]. Bian et al. carried out a study similar to the PROGNOSIS study in an Asian population, as the majority (>80%) of women in the previous PROGNOSIS study were white, with only ~5% of them having an Asian origin. This prospective, multicenter PROGNOSIS study was carried out to investigate the role of the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio in predicting adverse outcomes in suspected preeclamptic Asian women. The sFlt-1/PlGF ratio of ≤38 had a NPV of 98.6% (sensitivity of 76.5% and specificity of 82.1%) for ruling out PE within 1 week and NPV of 98.9% for ruling out fetal adverse outcomes within 1 week. The sFlt-1/PlGF ratio of >38 had a PPV (positive predictive value) of 30.3% (sensitivity of 62.0% and specificity of 83.9%) for ruling in PE within 4 weeks and a PPV of 53.5% for ruling in fetal adverse outcomes within 4 weeks. The study concluded that the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio cutoff of 38 carries significant clinical value for the short-term prediction of PE in suspected preeclamptic Asian women, helping physicians in Asia prevent unnecessary hospitalizations [93].

Sovio carried out a longitudinal study at ~20, 28 and 36 weeks of gestation in 265 nulliparous women who developed PE. A ratio >38 was considered positive for PE. The NPV of a ratio ≤38 for severe PE development in low-risk women at 36 weeks of gestation was 99.2%. The positive predictive value of a ratio >38 for PE development at 28 weeks was 32%; at 36 weeks, it was 20% for high-risk women and 6.4% for low-risk women. The ratio with a more severe increase (>85) predicted a nearly 60% risk of preterm delivery with PE. A ratio >110 had a positive predictive value of 30% for severe PE development at 36 weeks of gestation in both high- and low-risk women [94]. A recent review suggests three patient groups: those with a ratio <38 (highly unlikely to develop PE within a week), those with a ratio between 38 and 85 for early-onset and 38–110 for late-onset disease (may develop PE within 4 weeks) and those with a ratio >85–110 (very likely to have PE already). These risk levels can provide a basis for physicians to choose a better management plan, with the first group receiving outpatient care, the second group receiving frequent monitoring and ratio management, and the third group receiving close observation through hospitalization [2]. A meta-analysis by Agrawal et al. supported the ability of the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio to be used as a screening tool by reporting a pooled sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 92% of the ratio from 15 studies [95]. The abovementioned studies indicate the importance of the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio for possible assistance in the diagnosis of PE. There are many commercially available immunoassays for the measurement of sFlt-1 and PlGF concentration from blood samples. Stepan et al. carried out a study to compare the Elecsys (Roche Diagnostics, Manheim, Germany) and BRAHMS Kryptor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hennigsdorf, Germany) sFlt-1 and PlGF assays. The sFlt-1 and PlGF concentrations were measured from serum samples of pregnant women (n = 113, pregnant women with PE/HELLP syndrome and n = 270 controls) using Roche Elecsys and BRAHMS Kryptor sFlt-1/PlGF immunoassays. The study assessed gestation-specific cutoff values of ≤33, ≥85 and ≥110, which were validated using Elecsys immunoassays. The study reported significant differences in the mean values of PlGF and sFlt-1/PlGF calculated from the same samples using Elecsys and Kryptor immunoassays, despite the high correlation between these two types of assays. Based on the observations, the study concluded that the sFlt-1/PlGF cutoffs validated using Elecsys immunoassays are not transferable to Kryptor immunoassays. Further studies are required to determine optimal sFlt-1/PlGF cutoffs validated from Kryptor assays to aid in the diagnosis of PE [96].

Conclusion

Studies have explored the potential roles of various angiogenic factors, namely, VEGF, sFlt-1 and PlGF, as biomarkers for the specific diagnosis of PE. VEGF has been shown to be reduced throughout pregnancy and below the detection limit of most available ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) kits because of the sizeable rise in VEGF-binding proteins, such as sFlt-1; hence, free VEGF has failed to gain any further value as a biomarker. Attempts should be made to analyze the profile of total VEGF in maternal circulation in addition to free VEGF levels throughout gestation. PlGF can be a potential predictor for early-onset PE and its associated adverse outcomes. Most of the reported studies have analyzed PlGF levels between 11 and 14 weeks of gestation; however, more studies calculating PlGF concentration at ~29–32 weeks of gestation (where PlGF is considered to be at peak levels in normal pregnancies) in PE might provide a suitable time point for estimations of the progression and severity of PE in a woman. Compared to other angiogenic factors, there is less analysis of sEndoglin. On the other hand, the literature suggests that the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio has potential for risk stratification of pregnant women with suspected PE, leading to improved clinical outcomes.

There is still a lack of consistent and specific biomarkers for PE, especially in the first trimester of pregnancy. Most angiogenic markers have been found to be more useful in the prediction of early-onset disease and not late-onset PE. Although studies have found upregulated expression of antiangiogenic factors such as sFlt-1 and decreased levels of proangiogenic factors such as VEGF and PlGF, as evidence for an altered balance of angiogenic factors in women with PE compared to normotensive control women, these studies have certain limitations, such as small sample size with a limited number of PE cases, sample collection only at a single time point, the absence of gestational age matching during sample collection, enrollment of participants with a high risk of PE development, and enrollment of participants from different ethnic groups with variations in risk for PE development. Future studies need to confirm the earlier findings by taking into consideration the limitations of previous studies. More longitudinal studies are warranted to more clearly predict the potential of various angiogenic markers for the prediction of PE.

From the literature, it can be seen that angiogenic markers have a very high predictive value for adverse pregnancy outcomes, including intrauterine growth restriction, preterm birth, PE, eclampsia, placental abruption and postpartum hemorrhage, suggesting that angiogenic factors fail to provide specificity in the identification of PE. For specific prediction of PE, repeated measurements of angiogenic factors along with current diagnostic criteria in association with maternal family history, socioeconomic status and Doppler measures at various gestational time points might be helpful. A recent review evaluated the performance of angiogenic biomarkers along with clinical parameters and other biomarkers in the prediction of maternal/fetal adverse outcomes in women with placental dysfunction. The review concluded that collective information on placental perfusion (ultrasonography, MAP), clinical characteristics and biomarker levels (sFlt-1/PlGF ratio, PlGF) can improve the diagnosis of PE. The review also suggested a need to extend the definition of PE in American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and include the combination of new-onset hypertension and new-onset altered angiogenic factors (sFlt-1/PlGF ratio, PlGF) [97]. Despite this progress, further research regarding angiogenic factor profiles and specific cutoffs in twin pregnancies, high-risk populations, and populations with high disease prevalence is warranted. To the best of our knowledge, there are no longitudinal studies in the Indian population where there is a high prevalence of PE, maternal mortality and morbidity, along with limited health care facilities.

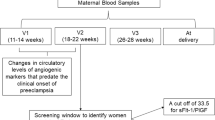

Considering the pronounced requirement for the development of predictive tools for PE, our group has initiated a study called the REVAMP (Research Exploring Various Aspects and Mechanisms in PE) study, which will help in the early identification of pregnant women who have a risk of PE development in the future and will aim to understand the underlying biochemical and molecular mechanisms involved in PE [98]. This study is following up a cohort of pregnant women from early gestation until delivery to longitudinally examine and study the profile of angiogenic growth factors VEGF, PlGF, sFlt-1, and sEndoglin across gestation to identify a potential biomarker for the prediction of PE and examine their associations with maternal nutrition, biochemical and molecular markers, and epigenetic modifications. The REVAMP study also has data on the personal, obstetric, clinical and family history of women, anthropometric measures, food frequency questionnaire, color Doppler measures, physical activity, fetal ultrasonography and socioeconomic status at different gestational time points. It is likely that the application of multivariable models considering the above factors may be more accurate and beneficial in the prediction of PE. By early identification of patients more prone to PE, it would be possible to reduce the severity of the disorder and improve maternal and child outcomes.

References

Schlembach D, Hund M, Wolf C, Vatish M. Diagnostic utility of angiogenic biomarkers in pregnant women with suspected preeclampsia: a health economics review. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2019;17:28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preghy.2019.03.002

Flint EJ, Cerdeira AS, Redman CW, Vatish M. The role of angiogenic factors in the management of preeclampsia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:700–707. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13540

Palmer KR, Tong S, Kaitu’u-Lino TJ. Placental-specific sFLT-1: role in pre-eclamptic pathophysiology and its translational possibilities for clinical prediction and diagnosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2016;23:69–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/molehr/gaw077

Govender N, Moodley J, Naicker T. The Use of Soluble FMS-like Tyrosine Kinase 1/Placental Growth Factor Ratio in the Clinical Management of Pre-eclampsia. Afr J Reprod Health. 2018;22:135–143. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2018/v22i1.14

Gupte S, Wagh G. Preeclampsia-eclampsia. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2014;64:4–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-014-0502-y

Gorakh Mandrupkar. FOGSI-GESTOSIS-ICOG Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy (HDP) Good Clinical Practice Recommendations 2019. The Federation Of Obstetric and Gynaecological Societies of India. https://www.fogsi.org/fogsi-hdp-gcpr-2019/.

Tranquilli AL, Dekker G, Magee L, Roberts J, Sibai BM, Steyn W, et al. The classification, diagnosis and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a revised statement from the ISSHP. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2014;4:97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preghy.2014.02.001

Duhig K, Vandermolen B, Shennan A. Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of pre-eclampsia. F1000Res. 2018;7:242. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.12249.1

Tomimatsu T, Mimura K, Matsuzaki S, Endo M, Kumasawa K, Kimura T. Preeclampsia: Maternal Systemic Vascular Disorder Caused by Generalized Endothelial Dysfunction Due to Placental Antiangiogenic Factors. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20174246

Cerdeira A, Agrawal S, Staff A, Redman C, Vatish M. Angiogenic factors: potential to change clinical practice in pre-eclampsia? BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy. 2018;125:1389–1395. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15042

Ali Z, Ali Z, Khaliq S, Zaki S, Ahmad HU, Lone KP. Differential Expression of Placental Growth Factor, Transforming Growth Factor-β and Soluble Endoglin in Peripheral Mononuclear Cells in Preeclampsia. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2019;29:235–239. https://doi.org/10.29271/jcpsp.2019.03.235

Adair TH, Montani JP. Angiogenesis. San Rafael (CA): Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2010. Chapter 1, Overview of Angiogenesis https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53238/

Maynard SE, Karumanchi SA. Angiogenic Factors and Preeclampsia. Semin Nephrol. 2011;31:33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2010.10.004

Hoeben A, Landuyt B, Highley MS, Wildiers H, Van Oosterom AT, De Bruijn EA. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Angiogenesis. Pharm Rev. 2004;56:549–580. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.56.4.3

Ngene NC, Moodley J. Role of angiogenic factors in the pathogenesis and management of pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;141:5–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12424

Holmes DIR, Zachary I. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family: angiogenic factors in health and disease. Genome Biol. 2005;6:209. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2005-6-2-209

Robinson CJ, Stringer SE. The splice variants of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and their receptors. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:853–865.

McCarthy FP, Ryan RM, Chappell LC. Prospective biomarkers in preterm preeclampsia: a review. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018;14:72–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preghy.2018.03.010

Esser S, Wolburg K, Wolburg H, Breier G, Kurzchalia T, Risau W. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces endothelial fenestrations in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:947–959. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.140.4.947

Zhu H, Gao M, Gao X, Tong Y. Vascular endothelial growth factor-B: impact on physiology and pathology. Cell Adh Migr. 2018;12:215–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/19336918.2017.1379634

Eddy AC, Bidwell GL, George EM. Pro-angiogenic therapeutics for preeclampsia. Biol Sex Differ. 2018;9:36 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-018-0195-5

Nissaisorakarn P, Sharif S, Jim B. Hypertension in Pregnancy: defining Blood Pressure Goals and the Value of Biomarkers for Preeclampsia. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18:131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-016-0782-1

Park SA, Jeong MS, Ha K-T, Jang SB. Structure and function of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor system. BMB Rep. 2018;51:73–78. https://doi.org/10.5483/bmbrep.2018.51.2.233

Lecarpentier E, Tsatsaris V. Angiogenic balance (sFlt-1/PlGF) and preeclampsia. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2016;77:97–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ando.2016.04.007

Thomas CP, Andrews JI, Liu KZ. Intronic polyadenylation signal sequences and alternate splicing generate human soluble Flt1 variants and regulate the abundance of soluble Flt1 in the placenta. FASEB J. 2007;21:3885–3895. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.07-8809com

Heydarian M, McCaffrey T, Florea L, Yang Z, Ross MM, Zhou W, et al. Novel splice variants of sFlt1 are upregulated in preeclampsia. Placenta. 2009;30:250–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2008.12.010

Souders CA, Maynard SE, Yan J, Wang Y, Boatright NK, Sedan J, et al. Circulating Levels of sFlt1 Splice Variants as Predictive Markers for the Development of Preeclampsia. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:12436–12453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms160612436

Palmer KR, Kaitu’u-Lino TJ, Hastie R, Hannan NJ, Ye L, Binder N, et al. Placental-Specific sFLT-1 e15a Protein Is Increased in Preeclampsia, Antagonizes Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Signaling, and Has Antiangiogenic Activity. Hypertension. 2015;66:1251–1259. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05883

Helmo FR, Lopes AMM. Carneiro ACDM, Campos CG, Silva PB, Dos Reis Monteiro MLG, et al. Angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. Pathol Res Pr. 2018;214:7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2017.10.021

Venkatesha S, Toporsian M, Lam C, Hanai J, Mammoto T, Kim YM, et al. Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nat Med. 2006;12:642–649. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1429

Kapur NK, Morine KJ, Letarte M. Endoglin: a critical mediator of cardiovascular health. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2013;9:195–206. https://doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S29144

Xu Y-T, Shen M-H, Jin A-Y, Li H, Zhu R. Maternal circulating levels of transforming growth factor-β superfamily and its soluble receptors in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;137:246–252. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12142

Saito S, Nakashima A. A review of the mechanism for poor placentation in early-onset preeclampsia: the role of autophagy in trophoblast invasion and vascular remodeling. J Reprod Immunol. 2014;101–102:80–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jri.2013.06.002

Su R-W, Fazleabas AT. Implantation and Establishment of Pregnancy in Human and Nonhuman Primates. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 2015;216:189–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15856-3_10

Rana S, Lemoine E, Granger JP, Karumanchi SA. Preeclampsia: pathophysiology, Challenges, and Perspectives. Circ Res. 2019;124:1094–1112. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313276

Rajakumar A, Brandon HM, Daftary A, Ness R, Conrad KP. Evidence for the functional activity of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors overexpressed in preeclamptic placentae. Placenta. 2004;25:763–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2004.02.011

Jauniaux E, Watson AL, Hempstock J, Bao YP, Skepper JN, Burton GJ. Onset of maternal arterial blood flow and placental oxidative stress. A possible factor in human early pregnancy failure. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:2111–2122. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64849-3

Smith RA, Kenny LC. Current thoughts on the pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia. Obstetrician Gynaecologist. 2006;8:7–13. https://doi.org/10.1576/toag.8.1.007.27202

Schrey-Petersen S, Stepan H. Anti-angiogenesis and Preeclampsia in 2016. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017;19:6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-017-0706-5

Livingston JC, Chin R, Haddad B, McKinney ET, Ahokas R, Sibai BM. Reductions of vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor concentrations in severe preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1554–1557. https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2000.108022

Maynard SE, Min J-Y, Merchan J, Lim K-H, Li J, Mondal S, et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Investig. 2003;111:649–658. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI17189

Laskowska M, Laskowska K, Leszczyńska-Gorzelak B, Oleszczuk J. Are the maternal and umbilical VEGF-A and SVEGF-R1 altered in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia with or without intrauterine foetal growth retardation? Preliminary communication. Med Wieku Rozwoj. 2008;12:499–506.

Baker PN, Krasnow J, Roberts JM, Yeo KT. Elevated serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:815–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-7844(95)00259-T

Sharkey AM, Cooper JC, Balmforth JR, McLaren J, Clark DE, Charnock-Jones DS, et al. Maternal plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in normotensive pregnancies and in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia. Eur J Clin Investig. 1996;26:1182–1185. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2362.1996.830605.x

Hunter A, Aitkenhead M, Caldwell C, McCracken G, Wilson D, McClure N. Serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in preeclamptic and normotensive pregnancy. Hypertension. 2000;36:965–969. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.hyp.36.6.965

Bosio PM, Wheeler T, Anthony F, Conroy R, O’herlihy C, McKenna P. Maternal plasma vascular endothelial growth factor concentrations in normal and hypertensive pregnancies and their relationship to peripheral vascular resistance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:146–152. https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2001.108342

Shaarawy M, Al-Sokkary F, Sheba M, Wahba O, Kandil HO, Abdel-Mohsen I. Angiogenin and vascular endothelial growth factor in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;88:112–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.10.005

Lee ES, Oh M-J, Jung JW, Lim J-E, Seol H-J, Lee K-J, et al. The levels of circulating vascular endothelial growth factor and soluble Flt-1 in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22:94–98. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2007.22.1.94

Kulkarni AV, Mehendale SS, Yadav HR, Kilari AS, Taralekar VS, Joshi SR. Circulating angiogenic factors and their association with birth outcomes in preeclampsia. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:561–567. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2010.31

Vaisbuch E, Whitty JE, Hassan SS, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Cotton DB, et al. Circulating angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in women with eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:152.e1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.049

Powers RW, Roberts JM, Plymire DA, Pucci D, Datwyler SA, Laird DM, et al. Low placental growth factor across pregnancy identifies a subset of women with preterm preeclampsia: type 1 versus type 2 preeclampsia? Hypertension. 2012;60:239–246. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.191213

Wei S-Q, Audibert F, Luo Z-C, Nuyt AM, Masse B, Julien P, et al. MIROS Study Group. Maternal plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, angiogenic factors, and preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:390.e1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2013.03.025

Smith GCS, Crossley JA, Aitken DA, Jenkins N, Lyall F, Cameron AD, et al. Circulating angiogenic factors in early pregnancy and the risk of preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, spontaneous preterm birth, and stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:1316–1324. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000265804.09161.0d

Sibiude J, Guibourdenche J, Dionne M-D, Le Ray C, Anselem O, Serreau R, et al. Placental growth factor for the prediction of adverse outcomes in patients with suspected preeclampsia or intrauterine growth restriction. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e50208. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050208

Cetin I, Mazzocco MI, Giardini V, Cardellicchio M, Calabrese S, Algeri P, et al. PlGF in a clinical setting of pregnancies at risk of preeclampsia and/or intrauterine growth restriction. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30:144–149. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2016.1168800

O’Gorman N, Wright D, Poon LC, Rolnik DL, Syngelaki A, de Alvarado M, et al. Multicenter screening for pre-eclampsia by maternal factors and biomarkers at 11-13 weeks’ gestation: comparison with NICE guidelines and ACOG recommendations. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49:756–760. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.17455

Poon LCY, Kametas NA, Maiz N, Akolekar R, Nicolaides KH. First-trimester prediction of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Hypertension. 2009;53:812–818. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.127977

Litwińska E, Litwińska M, Oszukowski P, Szaflik K, Kaczmarek P. Combined screening for early and late pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction by maternal history, uterine artery Doppler, mean arterial pressure and biochemical markers. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26:439–448. https://doi.org/10.17219/acem/62214

Duhig KE, Seed PT, Myers JE, Bahl R, Bambridge G, Barnfield S, et al. Placental growth factor testing for suspected pre-eclampsia: a cost-effectiveness analysis. BJOG. 2019;126:1390–1398. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15855

Wikström A-K, Larsson A, Eriksson UJ, Nash P, Olovsson M. Early postpartum changes in circulating pro- and anti-angiogenic factors in early-onset and late-onset pre-eclampsia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:146–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016340701819262

Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Espinoza J, Bujold E, Mee Kim Y, Gonçalves LF, et al. Evidence supporting a role for blockade of the vascular endothelial growth factor system in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Young Investigator Award. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1541–1547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2004.03.043. discussion 1547-1550

Kaufmann I, Rusterholz C, Hösli I, Hahn S, Lapaire O. Can detection of late-onset PE at triage by sflt-1 or PlGF be improved by the use of additional biomarkers? Prenat Diagn. 2012;32:1288–1294. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.3995

Furuya K, Kumasawa K, Nakamura H, Nishimori K, Kimura T. Novel biomarker profiles in experimental aged maternal mice with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:29–39. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-018-0092-7

Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim K-H, England LJ, Yu KF, et al. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N. Engl J Med. 2004;350:672–683. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa031884

Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, Yu KF, Maynard SE, Sachs BP, et al. CPEP Study Group. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:992–1005. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa055352

Sahay AS, Patil VV, Sundrani DP, Joshi AA, Wagh GN, Gupte SA, et al. A longitudinal study of circulating angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors and AT1-AA levels in preeclampsia. Hypertens Res. 2014;37:753–758. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2014.71

Rana S, Karumanchi SA, Levine RJ, Venkatesha S, Rauh-Hain JA, Tamez H, et al. Sequential changes in antiangiogenic factors in early pregnancy and risk of developing preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2007;50:137–142. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.087700

Hertig A, Berkane N, Lefevre G, Toumi K, Marti H-P, Capeau J, et al. Maternal serum sFlt1 concentration is an early and reliable predictive marker of preeclampsia. Clin Chem. 2004;50:1702–1703. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2004.036715

Romero R, Nien JK, Espinoza J, Todem D, Fu W, Chung H, et al. A longitudinal study of angiogenic (placental growth factor) and anti-angiogenic (soluble endoglin and soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1) factors in normal pregnancy and patients destined to develop preeclampsia and deliver a small for gestational age neonate. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:9–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050701830480

Krauss T, Pauer H-U, Augustin HG. Prospective analysis of placenta growth factor (PlGF) concentrations in the plasma of women with normal pregnancy and pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2004;23:101–111. https://doi.org/10.1081/PRG-120028286

Bersinger NA, Ødegård RA. Second- and third-trimester serum levels of placental proteins in preeclampsia and small-for-gestational age pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:37–45.

Erez O, Romero R, Espinoza J, Fu W, Todem D, Kusanovic JP, et al. The change in concentrations of angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors in maternal plasma between the first and second trimesters in risk assessment for the subsequent development of preeclampsia and small-for-gestational age. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:279–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050802034545

Kusanovic JP, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Erez O, Mittal P, Vaisbuch E, et al. A prospective cohort study of the value of maternal plasma concentrations of angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors in early pregnancy and midtrimester in the identification of patients destined to develop preeclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:1021–1038. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767050902994754

Perni U, Sison C, Sharma V, Helseth G, Hawfield A, Suthanthiran M, et al. Angiogenic factors in superimposed preeclampsia: a longitudinal study of women with chronic hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension. 2012;59:740–746. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.181735

Rizos D, Eleftheriades M, Karampas G, Rizou M, Haliassos A, Hassiakos D, et al. Placental growth factor and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 are useful markers for the prediction of preeclampsia but not for small for gestational age neonates: a longitudinal study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;171:225–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.08.040

Myatt L, Clifton RG, Roberts JM, Spong CY, Wapner RJ, Thorp JM, et al. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Can changes in angiogenic biomarkers between the first and second trimesters of pregnancy predict development of pre-eclampsia in a low-risk nulliparous patient population? BJOG. 2013;120:1183–1191. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12128

Khalil A, Maiz N, Garcia-Mandujano R, Elkhouli M, Nicolaides KH. Longitudinal changes in maternal soluble endoglin and angiopoietin-2 in women at risk for pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;44:402–410. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.13439

Khalil A, Maiz N, Garcia-Mandujano R, Penco JM, Nicolaides KH. Longitudinal changes in maternal serum placental growth factor and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 in women at increased risk of pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:324–331. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.15750

Erez O, Romero R, Maymon E, Chaemsaithong P, Done B, Pacora P, et al. The prediction of late-onset preeclampsia: Results from a longitudinal proteomics study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0181468 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181468

Jääskeläinen T, Heinonen S, Hämäläinen E, Pulkki K, Romppanen J, Laivuori H. FINNPEC. Angiogenic profile in the Finnish Genetics of Pre-Eclampsia Consortium (FINNPEC) cohort. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018;14:252–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preghy.2018.03.004

Teixeira PG, Reis ZSN, Andrade SP, Rezende CA, Lage EM, Velloso EP, et al. Presymptomatic prediction of preeclampsia with angiogenic factors, in high risk pregnant women. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2013;32:312–320. https://doi.org/10.3109/10641955.2013.807818

Sarween N, Drayson MT, Hodson J, Knox EM, Plant T, Day CJ, et al. Humoral immunity in late-onset Pre-eclampsia and linkage with angiogenic and inflammatory markers. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2018;80:e13041 https://doi.org/10.1111/aji.13041

Pinheiro CC, Rayol P, Gozzani L, Reis LM, dos, Zampieri G, Dias CB, et al. The relationship of angiogenic factors to maternal and neonatal manifestations of early-onset and late-onset preeclampsia. Prenat Diagn. 2014;34:1084–1092. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.4432

Zhang K, Zen M, Popovic NL, Lee VW, Alahakoon TI. Urinary placental growth factor in preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction: An alternative to circulating biomarkers? J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45:1828–1836. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.14038

Pant V, Yadav BK, Sharma J. A cross sectional study to assess the sFlt-1:PlGF ratio in pregnant women with and without preeclampsia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:266 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2399-z

Verlohren S, Galindo A, Schlembach D, Zeisler H, Herraiz I, Moertl MG, et al. An automated method for the determination of the sFlt-1/PIGF ratio in the assessment of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:161.e1–161.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.09.016

Verlohren S, Herraiz I, Lapaire O, Schlembach D, Moertl M, Zeisler H, et al. The sFlt-1/PlGF ratio in different types of hypertensive pregnancy disorders and its prognostic potential in preeclamptic patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:58.e1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.037

Verlohren S, Herraiz I, Lapaire O, Schlembach D, Zeisler H, Calda P, et al. New gestational phase-specific cutoff values for the use of the soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1/placental growth factor ratio as a diagnostic test for preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2014;63:346–352. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01787

Rana S, Schnettler WT, Powe C, Wenger J, Salahuddin S, Cerdeira AS, et al. Clinical characterization and outcomes of preeclampsia with normal angiogenic profile. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2013;32:189–201. https://doi.org/10.3109/10641955.2013.784788

Leaños-Miranda A, Méndez-Aguilar F, Ramírez-Valenzuela KL, Serrano-Rodríguez M, Berumen-Lechuga G, Molina-Pérez CJ, et al. Circulating angiogenic factors are related to the severity of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, and their adverse outcomes. Med (Baltim). 2017;96:e6005. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000006005

Hund M, Allegranza D, Schoedl M, Dilba P, Verhagen-Kamerbeek W, Stepan H. Multicenter prospective clinical study to evaluate the prediction of short-term outcome in pregnant women with suspected preeclampsia (PROGNOSIS): study protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:324 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-324

Zeisler H, Llurba E, Chantraine F, Vatish M, Staff AC, Sennström M, et al. Predictive Value of the sFlt-1:PlGF Ratio in Women with Suspected Preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:13–22. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1414838

Bian X, Biswas A, Huang X, Lee KJ, Li TK-T, Masuyama H, et al. Short-Term Prediction of Adverse Outcomes Using the sFlt-1 (Soluble fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase 1)/PlGF (Placental Growth Factor) Ratio in Asian Women With Suspected Preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2019;74:164–172. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.12760

Sovio U, Gaccioli F, Cook E, Hund M, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith GCS. Prediction of Preeclampsia Using the Soluble fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase 1 to Placental Growth Factor Ratio: a Prospective Cohort Study of Unselected Nulliparous Women. Hypertension. 2017;69:731–738. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08620

Agrawal S, Cerdeira AS, Redman C, Vatish M. Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review to Assess the Role of Soluble FMS-Like Tyrosine Kinase-1 and Placenta Growth Factor Ratio in Prediction of Preeclampsia: The SaPPPhirE Study. Hypertension. 2018;71:306–316. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10182

Stepan H, Hund M, Dilba P, Sillman J, Schlembatch D. Elecsys® and Kryptor immunoassays for the measurement of sFlt-1 and PlGF to aid preeclampsia diagnosis: are they comparable? Clin Chem Lab Med. 2019;57:1139–1348. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2018-1228

Stepan H, Hund M, Andraczek T. Combining Biomarkers to Predict Pregnancy Complications and Redefine Preeclampsia: The Angiogenic-Placental Syndrome. Hypertension. 2020;75:918–926. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13763

Wadhwani NS, Sundrani DP, Wagh GN, Mehendale SS, Tipnis MM, Joshi PC, et al. The REVAMP study: research exploring various aspects and mechanisms in preeclampsia: study protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:308 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2450-0

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) for funding the REVAMP (Research Exploring Various Aspects and Mechanisms in Preeclampsia) study (5/7/1069/13-RCH). Author AS thanks the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Government of India, for providing her the ‘RA fellowship’ (RBMH/FW/2019/17).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Deshpande, J.S., Sundrani, D.P., Sahay, A.S. et al. Unravelling the potential of angiogenic factors for the early prediction of preeclampsia. Hypertens Res 44, 756–769 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00647-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00647-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Maternal angiogenic factor disruptions prior to clinical diagnosis of preeclampsia: insights from the REVAMP study

Hypertension Research (2024)