Abstract

Although emerging data suggest that circulating lipoprotein (a) [Lp (a)] could predict cardiovascular events (CVEs) in patients with cardiovascular disease, no study is currently available regarding the prognostic linkage of Lp (a) and hypertension in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). This study sought to evaluate the association of Lp (a), hypertension and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with stable CAD. A total of 8668 patients with stable CAD were consecutively enrolled. Baseline Lp (a) concentrations were measured. All subjects were categorized according to Lp (a) levels of <10 (low), 10–30 (medium) and ≥30 mg/dL (high) and were further stratified by hypertension status. They were regularly followed-up for the occurrence of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and stroke. Over an average of 54.81 ± 18.60 months of follow-up, 584 (6.7%) CVEs occurred. Kaplan–Meier and multivariate Cox regression analyses showed that elevated Lp (a) levels had a significant association with CVEs in hypertensive patients, regardless of the control status of blood pressure, but not in normotensive subjects. Moreover, when analyzed by subgroups according to both Lp (a) category and hypertension status, the risk of CVEs was only significantly elevated in the high Lp (a) plus hypertension group compared with the reference group with low Lp (a) levels and normotension (hazard ratio: 1.80, 95% confidence interval: 1.11–2.91). Elevated Lp (a) was associated with an increased risk of CVEs in stable CAD patients with hypertension. Moreover, the coexistence of high Lp (a) concentrations and hypertension greatly worsened the clinical prognosis in patients with CAD, which may suggest a prognostic correlation between Lp (a) and hypertension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, lipoprotein (a) [Lp (a)] has been treated as one of the most attractive and promising novel cardiovascular risk factors [1]. Lp (a) is an atherogenic lipoprotein particle comprising a low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particle and the highly polymorphic apolipoprotein (a) [apo (a)], which is attached with a disulfide bond to apolipoprotein B-100 on the LDL core [1, 2]. The structural characteristics of Lp (a) may provide it with the ability to facilitate atherosclerosis and thrombosis [1]. Moreover, it has been suggested that Lp (a) could predict the incidence and prognosis of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [3,4,5,6,7], which has been demonstrated in some special populations as well, including postmenopausal women; patients with prediabetes or diabetes mellitus (DM), familial hypercholesterolemia, and premature coronary artery disease (CAD); patients following percutaneous coronary intervention; and patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) [1, 8,9,10,11,12].

Hypertension is one of the most common cardiovascular risk factors. Cardiovascular risk is correlated on a continuum with the level of blood pressure (BP) [2]. Adequate control of BP is of basic importance in cardiovascular prevention in hypertensive patients; however, BP is not the only determinant of cardiovascular damage, and the tendency of hypertensive patients to develop target organ damage is markedly influenced by coexisting risk factors, such as age, sex, smoking, obesity, DM and dyslipidemia [2, 13]. Among these factors, lipoproteins are essential to the atherosclerotic process and greatly influence the impact of hypertension on CVD morbidity and mortality [2].

Hypertension and dyslipidemia often occur together; however, few studies have evaluated the predictive role of Lp (a) for cardiovascular risk in patients with hypertension [2]. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies exploring the impact of Lp (a) on the association between hypertension and the risk of cardiovascular events (CVEs) in patients with angiography-proven stable CAD. Therefore, we conducted this prospective study in a large cohort of CAD patients with two aims: (i) to compare the predictive role of Lp (a) for CVEs in patients with or without hypertension and (ii) to investigate whether the combination of Lp (a) with hypertension could significantly aggravate CVD risk.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study design and population

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and Title 45, US Code of Federal Regulations, Part 46, Protection of Human Subjects, Revised November 13, 2001, effective December 13, 2001, and was approved by the hospital’s ethical review board (Fu Wai Hospital & National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, China). Each participant provided written informed consent before enrollment.

From March 2011 to July 2017, 11,437 consecutive Chinese patients who received coronary angiography because of angina-like chest pain and/or positive treadmill exercise test and/or significant stenosis indicated by coronary CT angiography were recruited from 3 medical centers, namely, FuWai Hospital, XuanWu Hospital and AnZhen Hospital, according to the same protocol. Based on elevated myocardial enzyme levels, typical electrocardiogram changes, positive findings by angiography and medical history, 1258 non-CAD patients and 1123 patients with ACS were excluded. Furthermore, 355 patients were excluded according to the criteria described in our previous studies [1, 14]. During the study, 33 patients were lost to follow-up. Eventually, 8668 subjects with stable CAD were enrolled in the study. According to their Lp (a) levels, patients were classified into 3 groups, namely, low (<10 mg/dL, n = 3228), medium (≥10 and <30 mg/dL, n = 2852), and high (≥30 mg/dL, n = 2588) (Fig. 1), and then they were further stratified by the presence or absence of hypertension. All enrolled patients were prescribed standard secondary prevention therapy for CAD.

Clinical assessment

Baseline information on personal health habits, demographic factors, medication use, and medical history was collected from each patient. According to our previous study [14], BP (first and fifth Korotkoff sounds) was measured 3 times consecutively in the first 3 days using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer by trained physicians. An appropriately sized cuff was selected by measuring each participant’s arm circumference. Participants were asked to sit for 5 min with their arm resting on the desk before the first measurement. There was a 30-s rest between BP measurements. The averages of the BP measurements were applied in the analysis. The traditional risk factors were defined as follows: [14] DM was diagnosed according to fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or the 2-h plasma glucose of the oral glucose tolerance test ≥11.1 mmol/L or currently using hypoglycemic drugs or insulin. Diagnosed hypertension was defined as self-reported hypertension and current use of prescribed antihypertensive drugs. Undiagnosed hypertension was defined by the 2018 ESC/ESH and 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines. According to the 2018 ESC/ESH criteria, patients with systolic BP (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg were diagnosed with hypertension [15]. Based on the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline, patients with SBP ≥ 130 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 80 mmHg were defined as having hypertension [16]. Total hypertension was the sum of the number of patients with diagnosed hypertension and undiagnosed hypertension. According to the 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines, controlled hypertension indicated that hypertensive patients with CAD had BP levels lower than 130/80 mmHg, while older patients (≥65 years) had BP levels lower than 140/80 mmHg [15]. Based on the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline, hypertensive patients with BP levels <130/<80 mmHg were defined as having controlled hypertension [16]. (Supplementary Table 1) The definition of baseline medication use was taking drugs continuously for at least 3 months before admission. Antihypertensive drug use included the use of β-blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics in all subjects.

Follow-up

All enrolled subjects were actively followed-up at 6-month intervals through clinical visits and/or telephone contact until July 2019 by well-trained nurses or cardiologists. The primary endpoints included cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke. All available relevant data from any reported possible event were collected. Cardiovascular death was defined as death primarily caused by acute MI, malignant arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, and other structural or functional cardiac diseases. Nonfatal MI was diagnosed by positive cardiac troponins along with typical chest pain or typical electrocardiogram serial changes. Stroke was defined according to persistent neurological dysfunction with documentation of acute cerebral infarction on computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging. Three experienced cardiologists who were blinded to the data classified the events independently. When their diagnoses were inconsistent, they discussed the case and made a final decision.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± SD or median (interquartile range) as appropriate. The differences between groups were determined using Student’s t-test, analysis of variance or nonparametric test where appropriate. Categorical variables are presented as numbers (percentages) and were analyzed by χ2-test or Fisher’s exact test. The event-free survival rates among groups were estimated by Kaplan–Meier analysis and compared by the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard models were used to calculate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A restricted cubic spline (RCS) adjusted for age and sex was created to assess linearity assumptions of the relationship between Lp (a) and CVEs. Additionally, we performed sensitivity analyses of the association between plasma Lp (a) concentrations and CVEs by separately adjusting for each of the other variables in the multivariate analysis and excluding subjects with Lp (a) levels in the top or bottom 5%. In the χ2 test, for comparisons between any two of the six groups, two-tailed p values <0.003 were considered statistically significant, while <0.05 was considered statistically significant in all the remaining analyses. The statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 24.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and STATA version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Role of the funding source

The funding organizations did not participate in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the decision to approve publication of the finished manuscript.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the entire study population as well as according to Lp (a) categories (<10, ≥10 and <30, and ≥30 mg/dL) are detailed in Table 1. The proportions of previous MI; coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) history; statin, β-blocker and antihypertensive drug use; and the concentrations of TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, and hsCRP were positively associated with Lp (a) levels. Meanwhile, patients with low Lp (a) levels were more likely to be males, smokers, and hypertensive, while the proportion of patients with well-controlled hypertension was higher in those with high Lp (a) levels.

Lp (a) levels, hypertension, and cardiovascular outcomes

Over an average of 54.81 ± 18.60 months of follow-up, 584 (6.7%) CVEs were recorded, including 234 cardiovascular deaths, 116 nonfatal MIs and 234 strokes. As presented in Supplementary Table 2, the event group had significantly higher Lp (a) levels than the nonevent group (20.34 vs. 14.92 mg/dL, p = 0.013). At the same time, patients in the event group were slightly older and more likely to have hypertension, DM, stroke, MI and CABG histories than those in the nonevent group. The levels of SBP, HbA1c, creatinine, and hsCRP in the event group were also significantly higher than those in the nonevent group. However, subjects in the event group had a lower left ventricular ejection fraction and were less likely to take statins and antihypertensive drugs at baseline.

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, for the entire population, the Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that subjects with medium (10–30 mg/dL) or high Lp (a) levels (≥30 mg/dL) had lower event-free survival rates than those with low Lp (a) levels (<10 mg/dL; p < 0.05 for both). In addition, patients with hypertension, diagnosed by either criterion, were more likely to suffer from CVEs than those with normal BP (p < 0.05 for both). When subjects were stratified by hypertension status, Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that in hypertensive patients defined according to the 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines, the medium and high Lp (a) groups still had lower event-free survival rates than the low Lp (a) group (p < 0.05). Moreover, regardless of whether their BP levels reached the target, high Lp (a) levels remained significantly associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes (p < 0.05 for both), while medium Lp (a) levels could only predict CVEs in patients whose BP was not well controlled (p = 0.006). However, in CAD patients without hypertension, we observed no significant association between Lp (a) levels and CVEs (p > 0.05 for both; Supplementary Fig. 2). Additionally, when hypertension was diagnosed by the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines, the results were similar (Supplementary Fig. 3).

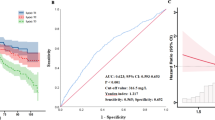

As shown in Supplementary Table 3, after adjustment for potential covariates, the association between medium and high levels of Lp (a) and CVEs in all subjects still existed. The adjusted HRs and 95% CIs of CVEs according to Lp (a) levels stratified by hypertension status are shown in Table 2. In hypertensive patients defined by the 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines, the high Lp (a) group had a 1.83-fold higher risk and the medium Lp (a) group had a 1.66-fold higher risk of CVEs than the low Lp (a) group in the crude model. Additional adjustment for other potential covariates did not change this association [high Lp (a) vs. low Lp (a): HR, 2.29, 95% CI: 1.53–3.44, p < 0.001; medium Lp (a) vs. low Lp (a): HR, 1.87, 95% CI: 1.25–2.80, p = 0.003). When hypertension was diagnosed according to the 2017 ACC/AHA criteria, subjects with high Lp (a) levels had an adjusted 2.11-fold (95% CI: 1.46–3.04, p < 0.001) increase, while those with medium Lp (a) levels had an adjusted 1.70-fold (95% CI: 1.18–2.45, p = 0.004) increase in the risk of CVEs compared with the reference group. Moreover, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4, RCS showed a strong trend toward a nonlinear positive association of Lp (a) with CVEs in our patients, mainly in those with hypertension. Based on both types of guidelines, the association between Lp (a) and CVEs in hypertensive CAD patients remained unchanged in a sensitivity analysis in which each of the other variables in the multivariate analysis was forced into the model with continuous Lp (a) (per 1-SD increase) (all p < 0.05, Supplementary Table 4). Additionally, the other sensitivity analysis performed by excluding subjects with extreme Lp (a) levels further demonstrated the association of Lp (a) with CVE risk in patients with CAD plus hypertension (Supplementary Table 5). Moreover, there was an ongoing relationship between high Lp (a) levels and cardiovascular outcomes in hypertensive patients, irrespective of whether BP met the treatment target (all p < 0.05 under two types of diagnostic criteria; Supplementary Table 6). Nevertheless, medium Lp (a) levels only had a significant association with CVEs in patients without well-controlled BP (HR: 1.89, 95% CI: 1.17–3.06, p = 0.009; and HR: 1.77, 95% CI: 1.15–2.73, p = 0.010, respectively; Supplementary Table 6). In CAD patients without hypertension defined according to either guideline, we observed no significant association between Lp (a) levels and CVEs (Table 2, all p > 0.05).

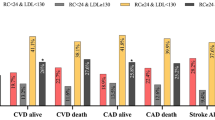

Furthermore, when the patients were evaluated according to Lp (a) levels and hypertension status together, the results showed that based on the 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines, hypertensive or normotensive patients with medium or high Lp (a) levels had a significantly higher incidence of CVEs than the reference group [-hypertension (HTN)/low Lp (a) group, Fig. 2a]. Meanwhile, the Kaplan–Meier analysis suggested that only hypertensive patients with medium or high Lp (a) levels had an increased risk of CVEs compared with the reference group (both p < 0.001, Fig. 2c). After adjusting for potential confounding factors in Cox models, compared with the -HTN/low Lp (a) group, elevated Lp (a) level or hypertension alone was not associated with increased CVE risk (all p > 0.05). However, high Lp (a) levels combined with hypertension did significantly increase the risk of developing CVEs when compared with the reference group, with an adjusted HR of 1.80 (95% CI, 1.11–2.91, Table 3). The interaction analysis showed that there was a statistically synergistic relationship between Lp (a) and hypertension [relative excess risk of interaction (RERI): 2.03, 95% CI, 0.19–4.25; attributable proportion (AP): 0.54, 95% CI, 0.36–0.72; synergy index: 3.75, 95% CI 2.72–5.16; all p < 0.001]. When hypertension was diagnosed according to the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines, the results were consistent (Fig. 2b, d; Table 3). The coexistence of hypertension and high Lp (a) levels was associated with a 1.88-fold higher risk of CVEs (95% CI: 1.10–3.22; Table 3). The sensitivity analysis performed by excluding subjects with extreme Lp (a) levels further demonstrated the enhanced predictive role of hypertension plus high Lp (a) levels for CVE risk (Supplementary Table 7).

The proportion of cardiovascular events and cumulative event-free survival analysis according to both baseline Lp (a) levels and hypertension status. a, c Hypertension was defined by the 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines. b, d Hypertension was defined by the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines. HTN hypertension; Lp (a), lipoprotein (a). *p < 0.005

Discussion

In this multicenter, prospective study on a sizable population with stable CAD, we, for the first time, indicated that elevated Lp (a) levels had a significant predictive role in the risk of CVEs in subjects with hypertension, irrespective of the control status of BP, defined by either the 2018 ESC/ESH or the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines. However, in CAD patients without hypertension, we observed no significant association between Lp (a) levels and CVEs. Moreover, when patients were categorized according to both Lp (a) levels and hypertension status, subjects with Lp (a) ≥30 mg/dL plus hypertension had a 1.80-fold increased risk of CVEs compared with those with Lp (a) <10 mg/dL and normal BP under the 2018 ESC/ESH diagnostic criteria. When hypertension was defined according to the 2017 ACC/AHA criteria, the risk of high Lp (a) (≥30 mg/dL) plus hypertension for CVEs was significantly increased by 1.88-fold. Our findings may present a prognostic linkage between hypertensive status and Lp (a) concentrations in patients with CAD, which should be evaluated further.

Currently, Lp (a) is widely accepted as a risk factor for CVD. Data from epidemiological and genetic studies have suggested that elevated Lp (a) is an independent risk factor for CVD incidence [3, 17,18,19,20]. The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration [21] performed a meta-analysis of 36 prospective studies with 1.3 million person-years of follow-up. They found that plasma Lp (a) concentrations had a continuous and independent association with the risk of CAD with an adjusted risk ratio of 1.13 (95% CI: 1.09–1.18). Furthermore, there is mounting evidence that Lp (a) plays a significant role in predicting CVE risk in patients with established CAD [1, 5,6,7, 10]. Among them is a meta-analysis of 18,979 CAD patients that indicated that Lp (a) levels in the highest quantile were significantly associated with an increased risk of CVEs [7]. Not surprisingly, in the present study, we also observed a significant association between elevated Lp (a) levels and CVEs in patients with stable CAD. Why did we divide the population according to Lp (a) levels of 10 and 30 mg/dL and not higher cutoff values? Previous studies have indicated that plasma Lp (a) concentrations are heritable and vary greatly across ethnic groups [1, 10, 22]. More than 90% of the variance in Lp (a) concentrations can be explained by genetics, and the relative contribution of environmental factors to the regulation of circulating Lp (a) levels is minimal [1, 10, 13]. Moreover, the concentrations of Lp (a) are lowest in Chinese individuals (median: 7.8 mg/dL, 5–95% range: 1.9–39.9 mg/dL), slightly higher in Europeans (9.6, 2.0–89.3), Southeast Asians (10.2, 2.0–53.6), Latin Americans (11.5, 2.0–77.2), and South Asians (13.8, 2.1–61.5) and even higher in Arabs (15.3, 2.0–66.8) and Africans (27.2, 3.3–102.4) [22]. Thus, we chose relatively lower cutoff values of Lp (a) in our study.

Hypertension is a universally recognized risk factor for CVD. Adequate control of BP is of basic importance in cardiovascular risk prevention in patients with hypertension, but correction of additional risk factors is an integral part of their management [13]. In addition to traditional risk factors, a number of novel cardiovascular risk factors have been identified in the general population, which might generate specific relevance in hypertensive patients [13]. A previous study indicated that Lp (a) was a strong predictor of the presence and severity of cardiovascular damage in hypertensive patients [2]. However, there have been no studies investigating the impact of Lp (a) on the association between hypertension and CVE risk in patients with stable CAD, let alone comparing the differences in the predictive role of Lp (a) in patients with or without hypertension. In this study, we interestingly found that the prediction effect of Lp (a) in CAD patients mainly existed in those with hypertension and that their BP control status had nothing to do with the effect of Lp (a). Moreover, the coexistence of hypertension and high Lp (a) levels (≥30 mg/dL) had a greatly enhanced predictive effect on the risk of CVEs. The significant association of Lp (a) with CVEs in hypertensive patients and the combined effects of Lp (a) and hypertension were further confirmed by sensitivity analyses. In addition, we adopted two types of recently published guidelines for the definition of hypertension and BP targets to better clarify the effect of Lp (a) on hypertension in predicting CVEs. However, in the present study, we observed no significant association between Lp (a) and CVE risk in patients with normal BP, which may be attributed to the relatively small sample size of this population. Regarding the association between Lp (a) and the prevalence of hypertension, the data obtained have been conflicting. Tangvarasittichai et al. [23] indicated that hypertensive patients had significantly higher Lp (a) levels than normotensive subjects. Nevertheless, some other studies found no significant differences in plasma Lp (a) levels between subjects with or without hypertension [2, 24, 25]. Interestingly, our data showed an inverse association between Lp (a) levels and hypertension prevalence. Thus, prospective studies in the future may be needed to further demonstrate the relationship between Lp (a) and the prevalence of hypertension.

The underlying mechanisms for the combined effects between high Lp (a) levels and hypertension are not fully understood. Hypertension damages endothelial function through hemodynamic changes, leading to endothelial dysfunction, increased inflammatory factors and oxidative stress, and upregulated adhesion molecule expression [14, 26, 27]. These effects are of great importance in initiating atherosclerosis, thrombosis and their complications [14, 26]. Meanwhile, the structural characteristics of Lp (a) determine its potential proatherogenic and prothrombotic effects. Lp (a) quantitatively possesses all the atherogenic ability of LDL particles, including the oxidizing tendency after migrating into the arterial walls, producing highly proinflammatory and immunogenic oxidized LDL [6]. The important homology between apo (a) and plasminogen suggests that Lp (a) might influence the activation of plasminogen to plasmin, thereby affecting fibrinolysis [13]. The potential role of Lp (a) as a prothrombotic factor has already been confirmed both in vitro and in vivo [28]. Additionally, Lp (a) may also have the ability to damage endothelial anticoagulant function by promoting endothelial dysfunction and increasing phospholipid oxidation [29, 30]. Thus, hypertension and elevated Lp (a) have similar mechanisms that increase cardiovascular risk, and it seems reasonable that their combination would contribute to a greater risk of CVEs than either one alone.

However, our study is limited by several facts. First, this is a study in Chinese patients with established CAD, and Lp (a) levels are known to vary with ethnicity, which might limit the generalizability of our findings. Second, in this study, Lp (a) was measured through an immunoturbidimetry method, which was not apo (a) isoform independent. However, a validated Lp (a) protein standard was used to calibrate the assay, along with linking the results to the World Health Organization (WHO)/International Federation of Clinical Chemistry (IFCC) and Laboratory Medicine International Reference Reagent, making the assay relatively isoform independent. Furthermore, for routine clinical care, currently available assays linked to the WHO/IFCC and laboratory medicine standards are able to detect high-risk patients with acceptable accuracy [6, 31]. Third, as is inherent in any observational and prospective study, our results are subject to confounding factors, and risk factor levels at baseline might change during the follow-up. Fourth, the relatively small number of patients without hypertension may influence the results of the association between Lp (a) and cardiovascular outcomes in this patient population. Thus, further studies in a large sample size of patients with normotension may be necessary.

In the present study, we first demonstrated that elevated Lp (a) levels were significantly associated with CVEs in hypertensive patients with stable CAD with a large sample size and long-term follow-up. Moreover, the coexistence of high Lp (a) concentrations and hypertension greatly worsened the prognosis of patients with stable CAD, suggesting that measurement of Lp (a) and treatment of high levels might be beneficial in CAD patients with hypertension.

References

Liu HH, Cao YX, Jin JL, Zhang HW, Hua Q, Li YF, et al. Predicting cardiovascular outcomes by baseline lipoprotein(a) concentrations: a large cohort and long-term follow-up study on real-world patients receiving percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014581.

Sechi LA, Catena C, Casaccio D, Zingaro L. Lipoprotein (a), haemostatic variables and cardiovascular damage in hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2000;18:709–16.

Kamstrup PR, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Steffensen R, Nordestgaard BG. Genetically elevated lipoprotein(a) and increased risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2009;301:2331–9.

Suk Danik J, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Lipoprotein(a), measured with an assay independent of apolipoprotein(a) isoform size, and risk of future cardiovascular events among initially healthy women. JAMA. 2006;296:1363–70.

Nestel PJ, Barnes EH, Tonkin AM, Simes J, Fournier M, White HD, et al. Plasma lipoprotein(a) concentration predicts future coronary and cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:2902–8.

Tsimikas S. A test in context: lipoprotein(a): diagnosis, prognosis, controversies, and emerging therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:692–711.

O’Donoghue ML, Morrow DA, Tsimikas S, Sloan S, Ren AF, Hoffman EB, et al. Lipoprotein(a) for risk assessment in patients with established coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:520–7.

Suk Danik J, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Lipoprotein(a), hormone replacement therapy, and risk of future cardiovascular events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:124–31.

Gragnano F, Fimiani F, Di Maio M, Cesaro A, Limongelli G, Cattano D, et al. Impact of lipoprotein(a) levels on recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with premature coronary artery disease. Intern Emerg Med. 2019;14:621–5.

Jin JL, Cao YX, Zhang HW, Sun D, Hua Q, Li YF, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular outcomes in coronary artery disease patients with prediabetes and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1312–18.

Li S, Wu NQ, Zhu CG, Zhang Y, Guo YL, Gao Y, et al. Significance of lipoprotein(a) levels in familial hypercholesterolemia and coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2017;260:67–74.

Zhou J, Cui X, Jin X, Zhou J, Fu M, Zhong C, et al. Association between Lipoprotein (a) level on admission and the incidence of subsequent cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2012;158:464–6.

Catena C, Novello M, Lapenna R, Baroselli S, Colussi G, Nadalini E, et al. New risk factors for atherosclerosis in hypertension: focus on the prothrombotic state and lipoprotein(a). J Hypertens. 2005;23:1617–31.

Liu HH, Cao YX, Li S, Guo YL, Zhu CG, Wu NQ, et al. Impacts of prediabetes mellitus alone or plus hypertension on the coronary severity and cardiovascular outcomes. Hypertension. 2018;71:1039–46.

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. European heart journal. 2018;39:3021–3104.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:1269–1324.

Bennet A, Di Angelantonio E, Erqou S, Eiriksdottir G, Sigurdsson G, Woodward M, et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of future coronary heart disease: large-scale prospective data. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:598–608.

Kamstrup PR, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Extreme lipoprotein(a) levels and improved cardiovascular risk prediction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1146–56.

Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, Kyriakou T, Goel A, Heath SC, et al. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N. Engl J Med. 2009;361:2518–28.

Consortium CAD, Deloukas P, Kanoni S, Willenborg C, Farrall M, Assimes TL, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies new risk loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:25–33.

Emerging Risk Factors C, Erqou S, Kaptoge S, Perry PL, Di Angelantonio E, Thompson A, et al. Lipoprotein(a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. JAMA. 2009;302:412–23.

Pare G, Caku A, McQueen M, Anand SS, Enas E, Clarke R, et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels and the risk of myocardial infarction among 7 ethnic groups. Circulation. 2019;139:1472–82.

Tangvarasittichai S, Pingmuanglaew P, Tangvarasittichai O. Association of elevated serum lipoprotein(a), inflammation, oxidative stress and chronic kidney disease with hypertension in non-diabetes hypertensive patients. Indian J Clin Biochem IJCB. 2016;31:446–51.

Steinmetz A, Kirklies A, Schlosser G, Cassel W, Peter JH, Ehlenz K, et al. Lipoprotein (a), low-density, intermediate-density lipoprotein, and blood pressure in a young male population. Clin Invest. 1993;71:145–9.

Sechi LA, Kronenberg F, De Carli S, Falleti E, Zingaro L, Catena C, et al. Association of serum lipoprotein(a) levels and apolipoprotein(a) size polymorphism with target-organ damage in arterial hypertension. JAMA. 1997;277:1689–95.

Huang Z, Chen C, Li S, Kong F, Shan P, Huang W. Serum markers of endothelial dysfunction and inflammation increase in hypertension with prediabetes mellitus. Genet Test Mol Biomark. 2016;20:322–7.

Wong WT, Tian XY, Huang Y. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes and hypertension: cross talk in RAS, BMP4, and ROS-dependent COX-2-derived prostanoids. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2013;61:204–14.

Jovin IS, Muller-Berghaus G. Interrelationships between the fibrinolytic system and lipoproteins in the pathogenesis of coronary atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2004;174:225–33.

Schachinger V, Halle M, Minners J, Berg A, Zeiher AM. Lipoprotein(a) selectively impairs receptor-mediated endothelial vasodilator function of the human coronary circulation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:927–34.

Bergmark C, Dewan A, Orsoni A, Merki E, Miller ER, Shin MJ, et al. A novel function of lipoprotein [a] as a preferential carrier of oxidized phospholipids in human plasma. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:2230–9.

Marcovina SM, Albers JJ. Lipoprotein (a) measurements for clinical application. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:526–37.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory at FuWai Hospital for their assistance in performing the studies. The authors also thank all the study investigators, staff, and patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, HH., Cao, YX., Jin, JL. et al. Lipoprotein (a), hypertension, and cardiovascular outcomes: a prospective study of patients with stable coronary artery disease. Hypertens Res 44, 1158–1167 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00668-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00668-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Cardiovascular endpoints and psychosocial challenges of lipoprotein(a) of 5726 participants in the ELITE-study over 5 years

Lipids in Health and Disease (2025)

-

Association of the systemic immune-inflammation index with clinical outcomes in acute myocardial infarction patients with hypertension

BMC Immunology (2025)

-

The triglyceride-glucose index positively associates with the prevalence and severity of coronary heart disease in patients among hypertension

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Multimodal prediction of major adverse cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease: integrating pericoronary fat radiomics, CT-FFR, and clinicoradiological features

La radiologia medica (2025)

-

The functions of apolipoproteins and lipoproteins in health and disease

Molecular Biomedicine (2024)