Abstract

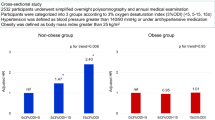

There is limited evidence regarding the combined effects of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) and alcohol consumption on hypertension. The aim of this study was to examine the combined effects of SDB and alcohol consumption on hypertension in Japanese male bus drivers. This cross-sectional study included 2525 Japanese male bus drivers aged 20–65 years. SDB was assessed using a single-channel airflow monitor, which measured the respiratory disturbance index (RDI) during overnight sleep at home. Alcohol consumption (g/day) was assessed by a self-administered questionnaire and calculated per unit of body weight. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg and/or use of antihypertensive medications. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to examine the association of the combined categories of RDI and alcohol consumption with hypertension. The multivariable-adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of hypertension for the alcohol consumption ≥1.0 g/day/kg and RDI ≥ 20 events/h group were 2.41 (1.45–4.00) compared with the alcohol consumption <1.0 g/day/kg and RDI < 10 events/h group. Our results suggest that Japanese male bus drivers with both SDB and excessive alcohol consumption are at higher risk of hypertension than those without SDB and excessive alcohol consumption, highlighting the importance of simultaneous management of SDB and excessive alcohol consumption to prevent the development of hypertension among bus drivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The high prevalence of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) among professional drivers is not only a health problem but also a social problem as it is a cause of disease-related traffic accidents [1, 2]. Hypertension is one of the most serious risk factors for CVDs [3]. Therefore, taking measures against hypertension is of paramount importance to prevent CVDs.

Several epidemiological studies have demonstrated that sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) is a risk factor for hypertension [4,5,6,7,8,9,10] and is associated with the incidence of CVDs, such as myocardial infarction, heart failure, and stroke [11,12,13]. Our recent study has also shown that SDB is associated with elevated central systolic blood pressure, which is a better predictor of future CVDs than brachial blood pressure [14]. These findings suggest that early detection and treatment of SDB is important in the overall management of hypertension [15]. On the other hand, alcohol consumption is also known to be a major risk factor for hypertension [16,17,18,19,20] and is also related to severe hypoxemia and severe SDB [21,22,23,24].

Although both SDB and alcohol consumption are associated with hypertension, the combined effects of alcohol consumption and SDB on hypertension remain unknown. We hypothesized that the combination of alcohol consumption and SDB would have a more harmful effect on the development of hypertension than either factor alone. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the combined effects of SDB and alcohol consumption on hypertension among Japanese male bus drivers.

Methods

Study population

This cross-sectional study was conducted between September 2013 and the end of September 2016, and all participants were recruited on a voluntary basis from 222 bus operating companies in 10 prefectures. The participants comprised mainly members of the Nihon Bus Association in Japan. Of the 4443 participants aged 20–82 years, all females (298 in total) were excluded due to the relatively small number compared to the number of males. In addition, 246 participants who were ≥66 years old and individuals lacking past data on SDB (n = 345), alcohol consumption (n = 235), and blood pressure (n = 708) were also excluded. The remaining 2525 men aged 20–65 years formed the study subjects. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Juntendo University Faculty of Medicine, and informed consent was obtained from each study participant.

Data collection

We collected a self-administered questionnaire to obtain information on systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and use of antihypertensive medications from each participant. Participants were asked to “fill in their recent blood pressure levels,” and they filled in their numerical SBP and DBP values. Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, DBP ≥ 90 mmHg and/or use of antihypertensive medications. Alcohol consumption was also assessed by a self-administered questionnaire. Participants were asked about the average amount of alcohol they drink per day over 1 week. Alcohol consumption was assessed in units of “go”, a Japanese unit of volume corresponding to 23 g ethanol, which was then converted to grams of ethanol per day. One “go” is equivalent to 180 ml of sake and corresponds to one bottle (633 ml) of beer, two single shots (75 ml) of whiskey, or two glasses (180 ml) of wine. It was then converted to grams of alcohol per body weight (kg). The study subjects were classified according to the amount of alcohol consumption into four groups: nondrinker group, <0.5 g/day/kg body weight group, 0.5 to <1.0 g/day/kg body weight group, and ≥1.0 g/day/kg body weight group, using the classification system of Tanigawa and colleagues [22].

Assessment of sleep-disordered breathing

SDB was evaluated noninvasively using a portable single-channel airflow monitor with the attached flow thermocouple sensor (SOMNIE; NGK Spark Plug, Nagoya, Japan). The device automatically measures the flow respiratory disturbance index (RDI), defined as the number of respiratory disturbance events per hour. Each subject was provided with instructions on the use of the monitor and the recording of breathing over the entire night at home [25, 26]. RDI is more sensitive than the oxygen desaturation index, and previous studies reported that RDI correlates with the apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) assessed by concurrent polysomnography (PSG) [25, 26]. The criterion for SDB was RDI levels of 10 and 20 events per hour, based on the findings that these RDI cutoffs represented AHIs of ≥5 and ≥15 events per hour, respectively, as determined by PSG, with corresponding sensitivities of 0.96 and 0.91 and specificities of 0.82 and 0.82 [25, 26].

Covariates

Age, height, weight and the number of cigarettes smoked per day were assessed by self-administered questionnaires. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of height in m2. Smoking status was classified into three categories: nonsmokers, 1–20, or ≥21 cigarettes per day. Current smokers were defined as individuals who smoked ≥1 cigarette/day.

Statistical analysis

The mean values of age, BMI, alcohol consumption, SBP and DBP; median RDI; and proportion of current smokers and individuals with hypertension were calculated according to the categories of alcohol consumption and RDI. Trend tests were performed by simple regression analysis and the chi-square test. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of hypertension, according to the categories of RDI and alcohol consumption. A linear trend was tested using the median values of RDI and alcohol consumption categories as the dependent variables in these models. Age (years), smoking status (nonsmokers, 1–20, or ≥21 cigarettes/day), BMI, RDI, and alcohol consumption were used as covariates. In addition, to assess the combined effect of alcohol consumption and SDB on hypertension, the combinations of alcohol consumption (<1.0 and ≥1.0 g/day/kg) and RDI (<10, ≥10, and <10, ≥20 events/h) were recategorized. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to examine the association between the combined categories and hypertension. In addition, we investigated whether there was an additive interaction between alcohol consumption and SDB. Relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) is the excess risk as a result of coexposure [27]. RERI was calculated using the following formula:

RERI = exponent (β1 + β2 + β3) − exponent (β1) − exponent (β2) + 1

(β1, β2, and β3 are the coefficients from the models for estimating odds ratios according to the combination of alcohol consumption and SDB.) A value of zero for RERI would mean there is no interaction, or exactly zero additivity; RERI > 0 would mean there is a positive interaction, or more than zero additivity; and RERI < 0 would mean there is a negative interaction, or less than zero additivity. RERI can range from negative infinity to positive infinity. All probability values for statistical tests were two-tailed, and values of p < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants according to RDI and alcohol consumption categories. Higher alcohol consumption was significantly associated with older age, higher SBP and DBP, higher RDI, higher proportion of smokers and individuals with hypertension, and lower BMI (p for trend <0.01). Furthermore, the mean values of age, BMI, and alcohol consumption; the median RDI; and the proportion of individuals with hypertension were higher depending on the severity of RDI (p for trend <0.01).

Table 2 shows that age- and multivariable-adjusted ORs (95% CI) of hypertension for the alcohol consumption groups (<0.5, 0.5 to <1.0, and ≥1.0 g/day/kg) were 1.33 (1.09–1.63), 1.79 (1.41–2.27), and 1.89 (1.40–2.55), respectively, compared with nondrinkers (p for trend <0.01). The results remained significant after further adjustment for RDI (p for trend <0.01).

Table 3 shows that age- and multivariable-adjusted ORs (95% CI) of hypertension for the RDI categories (10 to <20 events/h and ≥20 events/h) were 1.21 (0.99–1.48) and 1.29 (1.04–1.60), respectively, compared to the group with RDI < 10 events/h (p for trend = 0.03). The results remained marginally significant after further adjustment for alcohol consumption (p for trend = 0.053).

Table 4 shows age- and multivariable-adjusted ORs (95% CI) of hypertension according to the combination of alcohol consumption and RDI. The multivariable-adjusted ORs (95% CI) of hypertension for the group with alcohol consumption <1.0 g/day/kg and RDI ≥ 10 events/h, alcohol consumption ≥1.0 g/day/kg, and RDI < 10 events/h, and alcohol consumption ≥1.0 g/day/kg and RDI ≥ 10 events/h were 1.18 (0.98–1.43), 1.12 (0.65–1.92), and 1.89 (1.34–2.65), respectively, compared to those with alcohol consumption <1.0 g/day/kg and RDI < 10 events/h. Similarly, the multivariable-adjusted ORs (95% CI) of hypertension for the group with alcohol consumption <1.0 g/day/kg and RDI ≥ 20 events/h, alcohol consumption ≥1.0 g/day/kg and RDI < 10 events/h and alcohol consumption ≥1.0 g/day/kg and RDI ≥ 20 events/h were 1.19 (0.95–1.50), 1.12 (0.65–1.93), and 2.41 (1.45–4.00), respectively, compared to those with alcohol consumption <1.0 g/day/kg and RDI < 10 events/h. The RERI values for the combination of alcohol consumption of ≥1.0 g/day/kg with RDI ≥ 10 events/h or RDI ≥ 20 events/h were 0.59 (−0.25–1.42) and 1.10 (−0.22–2.42), respectively. This indicates that the combination of alcohol consumption and SDB did not have a significant supra-additive effect on hypertension.

Discussion

Our study showed that the severity of SDB and alcohol consumption were independently associated with hypertension among Japanese male bus drivers. The results of our study were consistent with those of previous epidemiological studies [4, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. We also analyzed the combined effect of alcohol consumption and SDB on hypertension. The results showed that participants with high RDI who were alcohol drinkers had higher ORs than those with either factor alone, even after adjustment for potential confounding factors. These results suggest that the combination of alcohol consumption and SDB seems to be more harmful to arterial blood pressure than either factor alone. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show the combined effect of alcohol consumption and SDB on hypertension in a large population of bus drivers.

In this study, the RERI values for the combination of alcohol consumption of ≥1.0 g/day/kg with RDI ≥ 10 events/h or RDI ≥ 20 events/h were 0.59 (−0.25–1.42) and 1.10 (−0.22–2.42), respectively, suggesting that there may be a supra-additive effect. However, we could not find a significant supra-additive effect of the combination of alcohol consumption and SDB on hypertension. This suggests that alcohol consumption and SDB are independently associated with hypertension via different pathways.

Our study population included higher proportions of individuals who were overweight (43%) and alcohol drinkers (62%) and who had a higher RDI (16.0 events/h) (not shown in tables) than the Japanese male general population (overweight: 31%, alcohol drinkers: 33%, RDI: 8.3 events/h) [28, 29]. These unhealthy characteristics are consistent with previous studies from the United States, which reported that 89% of professional drivers were overweight [30]. Obesity and alcohol intake are known important risk factors for SDB [10, 31], and these factors are independently associated with hypertension [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Thus, bus drivers may be at a higher risk of hypertension, and the combination of these risk factors may impose a higher risk of hypertension than each factor alone. These results emphasize the need for comprehensive approaches and measures, such as the Swiss cheese model, which is a model for mitigating the risk with different types of defense layers, to control hypertension among bus drivers [32].

What are the mechanisms mediating the biological effects of alcohol consumption and SDB on hypertension? While our study did not directly examine this issue, the potential mechanisms include baroreceptor impairment, destabilization of the central nervous system, and stimulation of the renin–angiotensin system [16]. On the other hand, the hypoxemia resulting from SDB associated with upper airway narrowing/obstruction possibly links SDB to hypertension [31, 33]. Hypoxemia results in increased sympathetic nerve activity and vasoconstriction, leading to hypertension [34]. Therefore, the risk of hypertension might be further increased in individuals with these two overlapping mechanisms.

The strength of this study was the analysis of the combined effect of alcohol consumption and SDB on hypertension in a large population of 2525 bus drivers after adjustment for potential confounding factors, allowing the results to be statistically robust. However, we acknowledge several limitations related to the study design. First, since the study was cross-sectional, no causal relationship could be confirmed. Second, a self-administered questionnaire was used to determine SBP and DBP in this study. Although the data were collected by a self-administered questionnaire, the validity of the self-report method in the assessment of these variables has already been confirmed with a high correlation (r = 0.73 for SBP, r = 0.67 for DBP) [35, 36]. Third, SDB was defined by RDI using a nasal flow sensor rather than by AHI based on overnight PSG. However, we have previously demonstrated a high correlation between RDI recorded by this technology and AHI assessed by polysomnography [26]. Fourth, although we examined the association of alcohol consumption and SDB with hypertension after adjustment for age, BMI, and smoking status, there are other potential confounding factors, e.g., work patterns, psychological stress, and diabetes. In this study, we could not control for these potential confounding factors because these data were not available in this study. Further studies are needed to consider these issues. Fifth, despite the large study population of 2525 bus drivers, they were recruited on a voluntary basis in this study. Therefore, we cannot guarantee the representativeness of our study population and need to be cautious in generalizing our findings to other populations.

Conclusions

The present study examined the combined effect of alcohol consumption and SDB on hypertension in Japanese male bus drivers, and the results demonstrated that the combination of alcohol consumption and SDB seems to be more harmful to arterial blood pressure than either factor alone. The simultaneous approach of both screening for SDB and health education on excessive alcohol consumption may be important in the management of hypertension among Japanese male bus drivers.

References

Bigert C, Gustavsson P, Hallqvist J, Hogstedt C, Lewne M, Plato N, et al. Myocardial infarction among professional drivers. Epidemiol (Camb, Mass). 2003;14:333–9.

Pedrinelli R, Ballo P, Fiorentini C, Denti S, Galderisi M, Ganau A, et al. Hypertension and acute myocardial infarction: an overview. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2012;13:194–202.

Oparil S, Acelajado MC, Bakris GL, Berlowitz DR, Cífková R, Dominiczak AF, et al. Hypertension. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2018;4:18014. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2018.14

Cui R, Tanigawa T, Sakurai S, Yamagishi K, Iso H. Relationships between sleep-disordered breathing and blood pressure and excessive daytime sleepiness among truck drivers. Hypertens Res. 2006;29:605–10.

Hou H, Zhao Y, Yu W, Dong H, Xue X, Ding J, et al. Association of obstructive sleep apnea with hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2018;8:010405. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.08.010405

Morgan BJ, Dempsey JA, Pegelow DF, Jacques A, Finn L, Palta M, et al. Blood pressure perturbations caused by subclinical sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep. 1998;21:737–46.

Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, Shahar E, Samet JM, Redline S, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA. 2000;283:1829–36.

Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1378–84.

Tanigawa T, Tachibana N, Yamagishi K, Muraki I, Kudo M, Ohira T, et al. Relationship between sleep-disordered breathing and blood pressure levels in community-based samples of Japanese men. Hypertens Res. 2004;27:479–84.

Young T, Peppard P, Palta M, Hla KM, Finn L, Morgan B, et al. Population-based study of sleep-disordered breathing as a risk factor for hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1746–52.

Kasai T, Bradley TD. Obstructive sleep apnea and heart failure: pathophysiologic and therapeutic implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:119–27.

Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet (Lond, Engl). 2005;365:1046–53.

Peker Y, Hedner J, Norum J, Kraiczi H, Carlson J. Increased incidence of cardiovascular disease in middle-aged men with obstructive sleep apnea: a 7-year follow-up. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:159–65.

Igami K, Maruyama K, Tomooka K, Ikeda A, Tabara Y, Kohara K, et al. Relationship between sleep-disordered breathing and central systolic blood pressure in a community-based population: the Toon Health Study. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1074–82.

Filomeno R, Ikeda A, Tanigawa T. Screening for sleep disordered breathing in an occupational setting. Juntendo Med J 2014;60:420–4.

Husain K, Ansari RA, Ferder L. Alcohol-induced hypertension: mechanism and prevention. World J Cardiol. 2014;6:245–52.

MacMahon S. Alcohol consumption and hypertension. Hypertension. 1987;9:111–21.

Ohmori S, Kiyohara Y, Kato I, Kubo M, Tanizaki Y, Iwamoto H, et al. Alcohol intake and future incidence of hypertension in a general Japanese population: the Hisayama study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1010–6.

Ikehara S, Iso H. Alcohol consumption and risks of hypertension and cardiovascular disease in Japanese men and women. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:477–81.

Nishigaki D, Yamamoto R, Shinzawa M, Kimura Y, Fujii Y, Aoki K, et al. Body mass index modifies the association between frequency of alcohol consumption and incidence of hypertension in men but not in women: a retrospective cohort study. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:322–30.

Issa FG, Sullivan CE. Alcohol, snoring and sleep apnea. J Neurol Neurosur Psychiatry 1982;45:353–9.

Tanigawa T, Tachibana N, Yamagishi K, Muraki I, Umesawa M, Shimamoto T, et al. Usual alcohol consumption and arterial oxygen desaturation during sleep. JAMA. 2004;292:923–5.

Sakurai S, Cui R, Tanigawa T, Yamagishi K, Iso H. Alcohol consumption before sleep is associated with severity of sleep-disordered breathing among professional Japanese truck drivers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:2053–8.

Peppard PE, Austin D, Brown RL. Association of alcohol consumption and sleep disordered breathing in men and women. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:265–70.

Nakano H, Tanigawa T, Furukawa T, Nishima S. Automatic detection of sleep-disordered breathing from a single-channel airflow record. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:728–36.

Nakano H, Tanigawa T, Ohnishi Y, Uemori H, Senzaki K, Furukawa T, et al. Validation of a single-channel airflow monitor for screening of sleep-disordered breathing. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1060–7.

Richardson DB, Kaufman JS. Estimation of the Relative Excess Risk Due to Interaction and Associated Confidence Bounds. AmJ Epidemiol. 2009;169:756–60.

Ministry of Health and Welfare. Annual report of the National Nutrition Survey in 2016. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/eiyou/h28-houkoku.html (In Japanese) Accessed 5 June 2020.

Yamagishi K, Ohira T, Nakano H, Bielinski SJ, Sakurai S, Imano H, et al. Cross-cultural comparison of the sleep-disordered breathing prevalence among Americans and Japanese. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:379–84.

Gurubhagavatula I, Maislin G, Nkwuo JE, Pack AI. Occupational screening for obstructive sleep apnea in commercial drivers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:371–6.

Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O’Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:47–112.

Wada H, Ikeda-Noda A, Kales S, Tanigawa T. Screening for sleep disordered breathing (SDB) in truck drivers in the US. Juntendo Med J. 2015;61:350–1.

Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, Kulhlmann DC, Mehra R, Ramar K, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnostic Testing for Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J CIin Sleep Med. 2017;13:479–504.

Narkiewicz K, Somers VK. Sympathetic nerve activity in obstructive sleep apnoea. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;177:385–90.

Kawada T, Takeuchi K, Suzuki S, Aoki S. Associations of reported and recorded height, weight and blood pressure. Jpn J Publ Hlth. 1994;41:1099–103. (In Japanese)

Okamoto N, Hosono A, Shibata K, Tsujimura S, Oka K, Fujita H, et al. Accuracy of self-reported height, weight and waist circumference in a Japanese sample. Obes Sci Pr. 2017;3:417–24.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the cooperation of the bus companies and bus drivers in this survey.

Funding

This research was supported by RISTEX, JST. RISTEX: Research Institute of Science and Technology for Society JST: Japan Science and Technology Agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sakiyama, N., Tomooka, K., Maruyama, K. et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing and alcohol consumption with hypertension among Japanese male bus drivers. Hypertens Res 44, 1168–1174 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00674-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00674-6