Abstract

To evaluate the effects of isometric handgrip exercise training (IHET) on blood pressure and heart rate variability in hypertensive subjects. Five databases were searched for randomized clinical trials in English, Spanish, or Portuguese evaluating the effect of IHET vs. no exercise on blood pressure (systolic and/or diastolic) and/or heart rate variability (low frequency [LF], high frequency [HF], and/or LF/HF ratio) through December 2020. Random-effects meta-analyses of mean differences (MDs) and/or standardized mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were performed. Five trials were selected (n = 324 hypertensive subjects), whose durations ranged from 8 to 10 weeks. Compared to no exercise, IHET reduced systolic blood pressure (MD −8.11 mmHg, 95% CI −11.7 to −4.53, p < 0.001) but did not affect diastolic blood pressure (MD −2.75 mmHg, 95% CI −9.47–3.96, p = 0.42), LF (SMD −0.14, 95% CI −0.65–0.37, p = 0.59), HF (SMD 0.38, 95% CI −0.14–0.89, p = 0.15), or the LF/HF ratio (SMD −0.22, 95% CI −0.95–0.52, p = 0.57). IHET performed for 8–10 weeks had a positive effect on resting systolic blood pressure but did not interfere with diastolic blood pressure or heart rate variability in hypertensive subjects. These data should be interpreted with caution since all volunteers included in the studies were clinically medicated and their blood pressure was controlled.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases remain the major cause of death and morbimortality worldwide. The prevalence has doubled since 1990, affecting 523 million people and causing 18.6 million deaths in 2019 [1]. There are multiple traditional risk factors for developing cardiovascular diseases, including cardiometabolic, behavioral, environmental, and social issues [2].

Hypertension remains the first modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease and plays a key role in cardiovascular outcomes, such as myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure [1]. Furthermore, hypertension can lead to autonomic imbalance assessed by heart rate variability (HRV), which is associated with immune dysfunction, chronic inflammation, and all-cause mortality [3,4,5]. Interventions become necessary to reverse these conditions.

Exercise training has been deemed an additional, nonpharmacological tool to treat hypertension. Traditionally, moderate aerobic exercise is the most recommended type of exercise for hypertensive subjects, as it reduces resting blood pressure by 8.9 mmHg [6]. However, recent studies have shown that dynamic resistance training can reduce resting blood pressure as much as or more than aerobic exercise [7,8,9]. Although the benefits of both aerobic and resistance training are unquestionable for hypertension treatment, personal, social, and economic factors can lead to low adherence and withdrawal of exercise programs, thus interrupting their benefits.

Isometric handgrip exercise training (IHET) has been proposed as a low-cost intervention with superior adherence compared to other exercise modalities [10, 11]. This type of exercise involves sustained contraction against an immovable load or resistance with minimal or no change in length of the muscle group involved [12]. The main concern over IHET in hypertensive subjects has been the prolonged cardiovascular response during muscle contractions, but recent studies have demonstrated safe blood pressure values during stress [13].

Previous studies have evaluated the effect of IHET on resting blood pressure and have shown significant reductions in systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) without any effect on HRV in normotensive individuals [14, 15]. However, studies involving hypertensive subjects remain scarce. Thus, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the effects of IHET on resting blood pressure and HRV in hypertensive subjects compared to no-exercise groups in randomized controlled trials. We hypothesized that IHET would reduce resting blood pressure but would not interfere with HRV.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines [16] and was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42020219089).

Eligibility criteria

We included randomized clinical trials that compared a group performing IHET with an exercise training protocol duration of at least 4 weeks against a nonexercise group (control group) and evaluated the resting blood pressure (systolic and/or diastolic) and/or HRV of treated hypertensive adults (over 18 years old) using frequency-domain parameters derived from the spectral analysis of heart rate, high frequency (HF), low frequency (LF), and HF/LF ratio. We excluded studies that involved normotensive or untreated hypertensive adults, evaluated the effect of two or more exercise modalities/interventions, evaluated the acute effect of IHET, and did not report the pre to postintervention or delta score in blood pressure or HRV.

Search strategy

We searched the PubMed, Europe PMC, Cochrane, Web of Science, Scielo, and SPORTDiscuss databases without language restrictions up to December 2020. We also searched for unpublished or ongoing trials using the System for Information on Gray Literature in Europe. We used the following terms: isometric handgrip AND exercise AND blood pressure AND HRV AND hypertension AND adults.

Study selection

Initially, two reviewers (LTPL and HR) independently screened the titles, abstracts, and, when necessary, the full texts from database records according to the eligibility criteria. Duplicates and articles that did not meet the criteria were removed. In the event of a disagreement between the two reviewers, a third reviewer was included. The reviewers were not blinded to the names or institutions of study authors or to journal titles.

Data extraction

The data extraction for all variables was performed by two independent researchers (JPASA and MB) using a customized Excel® spreadsheet. Then, the data were checked, and a third researcher was consulted in case of disagreement. The data extracted from the articles were as follows: (1) study details (i.e., year of publication, country of research); (2) number of initial participants involved in the study; (3) number of participants who finished the intervention; (4) training protocol; and (5) outcomes. Quantitative data from pre and posttraining interventions were extracted from the text, tables, and figures of articles and computed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). When the results were presented as the standard error of the mean, the standard error was converted to the SD.

Risk of bias and quality of evidence assessment

Two researchers (AL and LR) assessed the quality of the included studies using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for risk of bias [17]. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) tool was used to assess the quality of evidence per outcome, and each article was graded from high quality to very low quality [18].

Statistical analysis

We used a random-effects model for meta-analysis. For all studies, the delta (post-pre) values were calculated for outcomes, and the SD change was calculated according to the equation \(SD\,change \,=\, \surd [ {\left( {SDpre} \right)^2 \,+\, \left( {SDpost} \right)^2 \,-\, \left( {2 \times corr \times SDpre \times SDpost} \right)} ]\), where the imputed correlation coefficient was 0.5 [19]. Effects on blood pressure are presented as the mean differences, and HRV is presented as the standard mean difference (SMD), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Cochran’s Q-statistic and I2 test were performed to test for heterogeneity between studies. The heterogeneity thresholds for I2 were 25% (low), 50% (moderate), and 75% (high) [20]. Furthermore, the mean effect size was estimated by Hedges’ g test. Meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager 5.3 for Windows.

Results

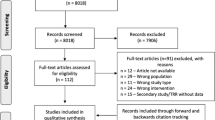

We searched the PubMed, Europe PMC, Cochrane, Web of Science, Scielo, and SPORTDiscuss databases and found 284 records. No additional records from other sources were found. From the total, 49 duplicates were removed, leaving 235 records. After screening titles and abstracts, 210 articles were excluded. The remaining 25 articles were read in full, and 20 were excluded. Therefore, five articles were included in the present study. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram.

Table 1 presents the details of the included studies: the age of the participants, prestudy resting blood pressure values, exercise training protocols, and main findings. A total of 330 volunteers were initially included, and 324 completed the study, representing a sample loss of 1.13%.

Risk of bias

We evaluated the risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration tool. Figure 2 shows the results. In our judgment, all included studies had a high risk of bias for not discussing the blinding of participants and personnel and the blinding of outcome assessment [21,22,23,24,25]. Furthermore, we deemed the following unclear: allocation concealment for all studies [21,22,23,24,25], selective reporting for four studies [21, 22, 24, 25], and other bias for three studies [23, 24].

Quality of evidence

We used GRADE to assess the quality of evidence. Table 2 shows the results. We found moderate evidence for SBP, DBP, HF, LF, and HF/LF. The (−1) downgrade was due to the lack of blinding information on study participants.

Meta-analyses

Blood pressure

All five included articles evaluated the effect of intervention with IHET on SBP and DBP [21,22,23,24,25]. As Fig. 3a illustrates, SBP was significantly reduced (MD −8.11 mmHg, 95% CI –11.7 to −4.53, p < 0.0001, I2 = 0%). However, no difference was observed in DBP (MD −2.75 mmHg, 95% CI −9.47–3.96, p = 0.42, I2 = 80%), as shown in Fig. 3b.

Heart rate variability

Three studies evaluated the effect of IHET on HF, LF, and the HF/LF ratio [22, 24, 25]. There was no significant difference in HF (SMD 0.38, 95% CI −0.14–0.89, p = 0.15, I2 = 0%) (Fig. 4a), LF (SMD −0.14, 95% CI −0.65–0.37, p = 0.59, I2 = 0%) (Fig. 4b), or HF/LF (SMD −0.22, 95% CI −0.95–0.52, p = 0.57, I2 = 49%) (Fig. 4c).

Discussion

Our study aimed to evaluate the effects of IHET on blood pressure and HRV in hypertensive subjects. We found a significant reduction in SBP with no effect on DBP or HRV. We can infer, then, that interventions using IHET are beneficial for treating hypertensive subjects. However, these data should be interpreted with caution since all volunteers included in the studies were clinically medicated and their blood pressure was properly controlled.

Our findings showed that IHET reduced SBP (mean 8.11 mmHg) but not DBP. These data are clinically relevant, as reduced SBP is associated with lower mortality from coronary heart disease, stroke, and other causes [26]. A previous study found similar reductions in SBP regardless of subject classification (normotensive, prehypertensive, hypertensive), but greater reductions were observed in prehypertensive populations [14]. Although the precise mechanisms that reduce SBP when using IHET have remained controversial, the explanation has focused on the reduction in systemic vascular resistance. This phenomenon could be explained by both the increase in endothelial-dependent vasodilation in response to reactive hyperemia—caused by isometric muscle contraction—and shear stress, which heightens the bioavailability of nitric oxide [8, 27,28,29]. Furthermore, one-leg isometric exercise training increased vessel endothelial function, artery diameter of trained limb, blood velocity, and blood flow and reduced vascular conductance [30]. Other factors, such as improved oxidative stress markers, reduced sympathetic activity, and ischemia-reperfusion processes, can explain this phenomenon [31,32,33]. Most volunteers had normalized DBP values at the beginning of the training due to the use of antihypertensive drugs with peripheral actions (i.e., angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, aldosterone antagonists, and diuretics). This could possibly explain why exercise had little influence on DBP.

Although all studies included in this meta-analysis were carried out with medicated individuals, two studies included volunteers with resting SBP above 140 mmHg. Based on the principle that a reduction in blood pressure is magnified in individuals with a higher resting blood pressure before the period of physical training, attention is warranted when interpreting the data from our study [34, 35]. We emphasize that all volunteers were clinically medicated, demonstrating that IHET could be a useful tool for improving resting blood pressure.

Acute and chronic factors may influence the blood pressure response immediately after physical exercise and at rest. Stress time (time of isometric contraction) is important for postexercise hypotension: the longer the stimulus time is, the higher the hypertensive peak will be—producing higher postexercise reactive hypotension. Thus, repeated physical training sessions can lead to chronic blood pressure adjustments [36]. The intensity of isometric contractions should also be considered. All five included studies performed IHET at 30% of maximum voluntary contration MVC. One study showed that IHET performed at different intensities (30% vs. 50% MVC) did not acutely promote cardiac overload and did not potentiate postexercise hypotension in this population. However, the protocol stress time in each bout was short (10 s), which could interfere with the analysis of results [13]. The intensity of exercise should be a considerable factor when the stress duration is longer; a higher intensity promotes higher postexercise hypotension [37]. We encourage new studies to evaluate and stabilize the ideal intensity zone of IHET that promotes the best hypotensive response.

As mentioned, when prescribing isometric exercises with prolonged stress time, one concern is that the longer the stress time is, the greater the hypertensive peak during exercise will be—and this is enhanced if a large muscle group is involved [38, 39]. Therefore, despite the need for further studies, we believe that since IHET uses a small muscle group, the hypertensive peak during stress is lower, making this type of exercise a viable and safe alternative.

Hypertensive subjects have autonomic dysfunction, with a lower HF domain and a larger LF and LF/HF domain. Low levels of HRV are associated with cardiac events, such as heart disease, heart failure, diabetes, and myocardial infarction [40,41,42]. Our results corroborate other studies that found no effect of resistance training on HRV [43,44,45,46]. However, a recent study suggested that aerobic exercise training has a positive effect on HRV, which could be explained by plasma catecholamine levels, nitric oxide levels, and neuromodulation [47, 48]. We believe that exercise training variables (frequency, intensity, and type of exercise) and time of intervention could interfere with HRV modulation. New studies with these variable manipulations using IHET are needed.

Our study has limitations. The small number of studies conducted with hypertensive people can directly influence the results found. Therefore, we encourage further research on IHET in this population using different intensities, contraction times, and intervention times. In addition, three studies evaluated the effect of IHET on HRV—possibly impairing the real analysis of the effect of physical exercise.

We encourage new studies to evaluate the effectiveness of IHET in hypertensive subjects using different intensities, stress times, types of execution, weekly frequencies, and intervention lengths. Such future studies can help define the ideal dose-response of hypertensive subjects to IHET.

Conclusion

We conclude that IHET performed for 8–10 weeks has a positive effect on SBP but no effect on DBP or HRV in hypertensive subjects.

References

Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2982–3021.

Jagannathan R, Patel SA, Ali MK, Narayan KMV. Global updates on cardiovascular disease mortality trends and attribution of traditional risk factors. Curr Diabetes Rep. 2019;19:44.

Tsuji H, Venditti FJ Jr., Manders ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, Feldman CL, et al. Reduced heart rate variability and mortality risk in an elderly cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1994;90:878–83.

Kiecolt-Glaser JK, McGuire L, Robles TF, Glaser R. Emotions, morbidity, and mortality: new perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:83–107.

Thayer JF, Yamamoto SS, Brosschot JF. The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Int J Cardiol. 2010;141:122–31.

Naci H, Salcher-Konrad M, Dias S, Blum MR, Sahoo SA, Nunan D, et al. How does exercise treatment compare with antihypertensive medications? A network meta-analysis of 391 randomised controlled trials assessing exercise and medication effects on systolic blood pressure. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:859–69.

MacDonald HV, Johnson BT, Huedo-Medina TB, Livingston J, Forsyth KC, Kraemer WJ, et al. Dynamic resistance training as stand-alone antihypertensive lifestyle therapy: a meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:1–7.

Cornelissen VA, Fagard RH. Effect of resistance training on resting blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens. 2005;23:251–259.

Pescatello LS, MacDonald HV, Lamberti L, Johnson BT. Exercise for hypertension: a prescription update integrating existing recommendations with emerging research. Curr hypertension Rep. 2015;17:87.

Millar PJ, Bray SR, McGowan CL, MacDonald MJ, McCartney N. Effects of isometric handgrip training among people medicated for hypertension: a multilevel analysis. Blood Press Monit. 2007;12:307–14.

Millar PJ, Bray SR, MacDonald MJ, McCartney N. The hypotensive effects of isometric handgrip training using an inexpensive spring handgrip training device. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2008;28:203–207.

Lind AR. Cardiovascular adjustments to isometric contractions: static effort. Compr Physiol. 2011:1;947–66.

Olher RDRV, Bocalini DS, Bacurau RF, Rodriguez D, Figueira A Jr, Pontes FL Jr, et al. Isometric handgrip does not elicit cardiovascular overload or post-exercise hypotension in hypertensive older women. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:649.

Jin YZ, Yan S, Yuan WX. Effect of isometric handgrip training on resting blood pressure in adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J sports Med Phys Fit. 2017;57:154–60.

Farah BQ, Christofaro DGD, Correia MA, Oliveira CB, Parmenter BJ, Ritti-Dias RM. Effects of isometric handgrip training on cardiac autonomic profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis study. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2020;40:141–147.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60.

Badrov MB, Horton S, Millar PJ, McGowan CL. Cardiovascular stress reactivity tasks successfully predict the hypotensive response of isometric handgrip training in hypertensives. Psychophysiology. 2013;50:407–14.

Millar PJ, Levy AS, McGowan CL, McCartney N, MacDonald MJ. Isometric handgrip training lowers blood pressure and increases heart rate complexity in medicated hypertensive patients. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2013;23:620–626.

Punia S, Kulandaivelan S. Home-based isometric handgrip training on RBP in hypertensive adults-Partial preliminary findings from RCT. Physiother Res Int. 2020;25:e1806.

Stiller-Moldovan C, Kenno K, McGowan CL. Effects of isometric handgrip training on blood pressure (resting and 24 h ambulatory) and heart rate variability in medicated hypertensive patients. Blood Press Monit. 2012;17:55–61.

Taylor AC, McCartney N, Kamath MV, Wiley RL. Isometric training lowers resting blood pressure and modulates autonomic control. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:251–256.

Bowling CB, Davis BR, Luciano A, Simpson LM, Sloane R, Pieper CF, et al. Sustained blood pressure control and coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, and mortality: an observational analysis of ALLHAT. J Clin Hypertens. 2019;21:451–459.

McGowan CL, Visocchi A, Faulkner M, Verduyn R, Rakobowchuk M, Levy AS, et al. Isometric handgrip training improves local flow-mediated dilation in medicated hypertensives. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007;99:227–34.

Kingwell BA. Nitric oxide-mediated metabolic regulation during exercise: effects of training in health and cardiovascular disease. FASEB J. 2000;14:1685–96.

Higashi Y, Yoshizumi M. Exercise and endothelial function: role of endothelium-derived nitric oxide and oxidative stress in healthy subjects and hypertensive patients. Pharmacol Therapeutics. 2004;102:87–96.

Baross AW, Wiles JD, Swaine IL. Effects of the intensity of leg isometric training on the vasculature of trained and untrained limbs and resting blood pressure in middle-aged men. Int J Vasc Med. 2012;2012:964697.

Peters PG, Alessio HM, Hagerman AE, Ashton T, Nagy S, Wiley RL. Short-term isometric exercise reduces systolic blood pressure in hypertensive adults: possible role of reactive oxygen species. Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:199–205.

Santangelo L, Cigliano L, Montefusco A, Spagnuolo MS, Nigro G, Golino P, et al. Evaluation of the antioxidant response in the plasma of healthy or hypertensive subjects after short-term exercise. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:791–798.

Kelley GA, Kelley KS. Isometric handgrip exercise and resting blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens. 2010;28:411–418.

Ruivo JA, Alcantara P. [Hypertension and exercise]. Rev Port Cardiol. 2012;31:151–158.

Boutcher YN, Boutcher SH. Exercise intensity and hypertension: what’s new? J Hum Hypertens. 2017;31:157–64.

Brito LC, Fecchio RY, Peçanha T, Andrade-Lima A, Halliwill JR, Forjaz CL. Postexercise hypotension as a clinical tool: a “single brick” in the wall. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2018;12:e59–e64.

Souza LR, Vicente JB, Melo GR, Moraes VC, Olher RR, Sousa IC, et al. Acute hypotension after moderate-intensity handgrip exercise in hypertensive elderly people. J Strength Conditioning Res. 2018;32:2971–2977.

Nascimento DDC, da Silva CR, Valduga R, Saraiva B, de Sousa Neto IV, Vieira A, et al. Blood pressure response to resistance training in hypertensive and normotensive older women. Clin Inter Aging. 2018;13:541–53.

Zanetti HR, Ferreira AL, Haddad EG, Gonçalves A, Jesus LFD, Lopes LTP. Análise das respostas cardiovasculares agudas ao exercício resistido em diferentes intervalos de recuperação. %J Rev Brasileira de Med do Esport. 2013;19:168–70.

Bilchick KC, Fetics B, Djoukeng R, Fisher SG, Fletcher RD, Singh SN, et al. Prognostic value of heart rate variability in chronic congestive heart failure (Veterans Affairs’ Survival Trial of Antiarrhythmic Therapy in Congestive Heart Failure). Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:24–28.

Galinier M, Pathak A, Fourcade J, Androdias C, Curnier D, Varnous S, et al. Depressed low frequency power of heart rate variability as an independent predictor of sudden death in chronic heart failure. Eur heart J. 2000;21:475–82.

Routledge FS, Campbell TS, McFetridge-Durdle JA, Bacon SL. Improvements in heart rate variability with exercise therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26:303–312.

Cooke WH, Carter JR. Strength training does not affect vagal-cardiac control or cardiovagal baroreflex sensitivity in young healthy subjects. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2005;93:719–25.

Heffernan KS, Fahs CA, Shinsako KK, Jae SY, Fernhall B. Heart rate recovery and heart rate complexity following resistance exercise training and detraining in young men. Am J Physiol Heart circulatory Physiol. 2007;293:H3180–3186.

Karavirta L, Tulppo MP, Laaksonen DE, Nyman K, Laukkanen RT, Kinnunen H, et al. Heart rate dynamics after combined endurance and strength training in older men. Med Sci sports Exerc. 2009;41:1436–43.

Collier SR, Kanaley JA, Carhart R Jr, Frechette V, Tobin MM, Bennett N, et al. Cardiac autonomic function and baroreflex changes following 4 weeks of resistance versus aerobic training in individuals with pre-hypertension. Acta Physiologica. 2009;195:339–48.

Sandercock GR, Bromley PD, Brodie DA. Effects of exercise on heart rate variability: inferences from meta-analysis. Med Sci sports Exerc. 2005;37:433–439.

Besnier F, Labrunee M, Pathak A, Pavy-Le Traon A, Gales C, Senard JM, et al. Exercise training-induced modification in autonomic nervous system: an update for cardiac patients. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;60:27–35.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Almeida, J.P.A.d.S., Bessa, M., Lopes, L.T.P. et al. Isometric handgrip exercise training reduces resting systolic blood pressure but does not interfere with diastolic blood pressure and heart rate variability in hypertensive subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Hypertens Res 44, 1205–1212 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00681-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00681-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Efficacy and moderators of isometric resistance training (IRT) on resting blood pressure among patients with pre- to established hypertension: a multilevel meta-review and regression analysis

BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation (2025)

-

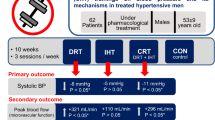

Effects of dynamic, isometric and combined resistance training on blood pressure and its mechanisms in hypertensive men

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

The effectiveness and safety of isometric resistance training for adults with high blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Hypertension Research (2021)