Abstract

Current studies have shown the controversial effect of genetic risk scores (GRSs) in hypertension prediction. Machine learning methods are used extensively in the medical field but rarely in the mining of genetic information. This study aims to determine whether genetic information can improve the prediction of incident hypertension using machine learning approaches in a prospective study. The study recruited 4592 subjects without hypertension at baseline from a cohort study conducted in rural China. A polygenic risk score (PGGRS) was calculated using 13 SNPs. According to a ratio of 7:3, subjects were randomly allocated to the train and test datasets. Models with and without the PGGRS were established using the train dataset with Cox regression, artificial neural network (ANN), random forest (RF), and gradient boosting machine (GBM) methods. The discrimination and reclassification of models were estimated using the test dataset. The PGGRS showed a significant association with the risk of incident hypertension (HR (95% CI), 1.046 (1.004, 1.090), P = 0.031) irrespective of baseline blood pressure. Models that did not include the PGGRS achieved AUCs (95% CI) of 0.785 (0.763, 0.807), 0.790 (0.768, 0.811), 0.838 (0.817, 0.857), and 0.854 (0.835, 0.873) for the Cox, ANN, RF, and GBM methods, respectively. The addition of the PGGRS led to the improvement of the AUC by 0.001, 0.008, 0.023, and 0.017; IDI by 1.39%, 2.86%, 4.73%, and 4.68%; and NRI by 25.05%, 13.01%, 44.87%, and 22.94%, respectively. Incident hypertension risk was better predicted by the traditional+PGGRS model, especially when machine learning approaches were used, suggesting that genetic information may have the potential to identify new hypertension cases using machine learning methods in resource-limited areas.

Clinical trial registration

The Henan Rural Cohort Study has been registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Register (Registration number: ChiCTR-OOC-15006699). http://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.aspx?proj=11375.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension, a chronic disease prevalent throughout the world, is the most common risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and it common has environmental and inherited causes [1,2,3]. A large number of genome-wide association studies have identified multiple single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of susceptibility genes associated with hypertension and/or elevated blood pressure levels [4,5,6]. Indeed, several studies have discussed whether the combination of genetic and traditional factors can improve hypertension prediction efficacy. An essential hypertension risk model including both traditional factors and 4 SNPs was established and indicated the critical roles of genetic factors in hypertension [7]. However, due to the relatively low magnitude predictive ability of a single SNP, the predictive ability may improve by combining nonsignificant SNPs into genetic risk scores (GRSs). A study conducted in Sweden confirmed that a GRS was independently related to incident hypertension but did not contribute to the predictive ability of the model [8]. However, two studies from Korea and China concluded that the addition of a GRS provided limited but positive improvements to traditional models. However, no relevant studies have been conducted in resource-limited areas [9, 10].

In recent years, a fair number of studies have applied machine learning methods to medical data and successfully solved various medical problems, especially disease prediction [11, 12]. Machine learning methods have advanced applications for which classical methods are not well suited due to the high data utilization requirement. Complicated diseases can be easily and better described and predicted by machine learning methods [13]. More importantly, artificial neural network (ANN), random forest (RF), and gradient boosting machine (GBM) methods have been shown to have better performance among various machine learning methods in rural China populations [12, 14]. Considering the uncertainty of the effect of GRS on the prediction of hypertension, this study aims to explore whether genetic information is an important factor in hypertension prediction using machine learning methods in resource-limited districts from a prospective cohort study conducted in rural China.

Methods

Subjects and measurements

The Henan Rural Cohort study is a prospective study based on a large-scale rural population in a resource-limited area in China that aims to explore the possible risk factors for noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and the prevention of NCDs in the Chinese rural population. The baseline data of the study were collected between July 2015 and September 2017. Subsequent follow-up surveys were conducted every 3 years starting in 2018 [15]. The current analysis used the population dedicated to the examination of genetic factors, including 8268 subjects who had undergone complete SNP testing. The following subjects were excluded: (1) those who were missing genetic information, (2) those who had prevalent hypertension at baseline, and (3) those who had missing data on the outcome. Therefore, a total of 4592 (aged 18–81 years) subjects were enrolled in the present analysis. All the subjects signed written informed consent forms. This study was approved by the Zhengzhou University Life Science Ethics Committee.

Demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, personal history of disease, family history of disease, etc. were assessed through a questionnaire interview conducted by well-trained investigators. Anthropometric measurements including height, weight, waist circumference, hip circumference, blood pressure, etc. were obtained for each subject. Venous blood samples were collected after 8 h of overnight fasting for routine blood examination. Less fruits and vegetables intake was defined as taking less than 500 g of fruit and vegetables per day. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by height squared (kg/m2). Physical activity was classified into 3 levels (low, moderate, high) according to the International Physical Activity Questionnaire recommended by WHO. Pulse pressure was calculated as systolic blood pressure (SBP) - diastolic blood pressure (DBP).

Hypertension

The blood pressure of subjects was measured after at least 5 min of rest and no consumption of tea, alcohol, or cigarettes or performance of excessive physical activity. Each subject had their blood pressure measured at least three times, and the average of those measurements was taken as the final blood pressure. According to the China Hypertension Prevention Guide (2010 Revision) [16], blood pressure greater than or equal to 140/90 mmHg or a physician diagnosis of hypertension and use of medication in the last two weeks was determined as hypertension.

Polygenetic risk score

A total of 13 SNPs (rs11191548, rs1275988, rs16849225, rs7136259, rs17249754, rs2107595, rs9810888, rs10745332, rs1378942, rs16998073, rs1902859, rs2021783, rs7577262) reported to be related to hypertension were integrated into a polygenic genetic risk score (PGGRS). Considering the target population of this study, the 13 SNPs were selected from the literature in conjunction with reports from large GWAS in East Asia [17,18,19,20,21]. These 13 SNPs were subsequently replicated in the present population. SNPs were detected by a custom SNPscan™ kit (Genesky Biotechnologies Inc., Shanghai, China). The PGGRS was calculated based on a genetic codominance model, which codes genotypes in the form of dummy variables (e.g., AA is coded as 00, Aa is coded as 10, and aa is coded as 01), calculates the risk coefficient for each genotype relative to the reference genotype (shown in Supplementary Table 1), and finally sums all the risk coefficients for each individual to obtain the PGGRS.

Model construction and evaluation

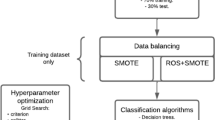

All models were constructed and fitted using the train dataset, involving a randomly selected group of 70% of subjects (n = 3214). The predictive performance of the models was assessed using the test dataset, involving the remaining 30% of subjects (n = 1378).

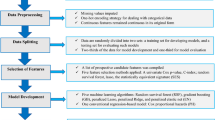

The models were constructed using the train dataset to predict the probability of incident hypertension over 3 years, and the process was as follows: First, risk factors that significantly associated with the development of hypertension was screened using the univariate Cox regression (results were shown in Supplementary Table 2); Second, among these associated risk factors, the stepwise method of multivariate Cox regression (P < 0.05 for inclusion, P > 0.10 for exclusion) was used to screen the predictors of incident hypertension (results were shown in Table 2). The screened predictors composed the traditional model. These traditional predictors together with PGGRS constituted the traditional+PGGRS model. Third, the models were constructed using the Cox regression methods (performed in SPSS (21.0)) and machine learning methods, including ANN, RF, and GBM (performed in Python (3.8), package: sklearn (0.21.3)) [22,23,24,25,26]. The parameters of machine learning models were selected using 10-fold cross-validation and grid search methods, while the process of parameter selection was repeated 100 times to obtain robust results. In this study, the parameters with the best area under the receiver operator characteristic curves (AUCs) were used to construct the prediction model.

In the test dataset, the improvement in discrimination was examined by comparing the AUC with or without the GRS in traditional models [27]. The integrated discrimination improvement index (IDI) and net reclassification improvement index (NRI) were also calculated [28, 29]. The decision curve was used to examine the clinical benefits of the predictive model [30]. A flowchart of model construction and evaluation is provided in the supplementary material (Supplementary Fig. 1) to present the whole process.

Statistical analysis

The mean and standard deviation are used to describe continuous variables, and differences were tested by the t-test. For classification variables, frequency and proportion were adopted, and the difference was tested by chi-square.

In addition, another two types of GRSs (SGRS and DLGRS) were calculated and analyzed as sensitivity analyses. The predictive ability of SGRS and DLGRS in the development of hypertension was analyzed and is provided in the supplementary material.

All statistical tests were two-sided, with P < 0.05 indicating statistical significance. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 21.0, R version 4.0.0, and Python 3.8.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline demographic characteristics of the subjects in the total population, train dataset, and test dataset are summarized in Table 1. Among 4592 subjects, the 3-year incidence of hypertension was 18.90%, with 868 participants developing hypertension. The average age was 49.04 ± 11.52 years old, and 63% of participants were women. Concerning baseline characteristics, no significant difference was observed between the train dataset and test dataset (all P > 0.05).

Performance of models with and without the PGGRS

Table 2 shows the predictors in the traditional model, which were age, less fruits and vegetables intake, family history of hypertension, physical activity, BMI, baseline DBP, and pulse pressure. All the variables were significantly related to incident hypertension. As shown in Table 3, the AUCs were 0.785 (0.763, 0.807), 0.790 (0.768, 0.811), 0.838 (0.817, 0.857) and 0.854 (0.835, 0.873) for traditional models with the Cox, ANN, RF, and GBM methods, respectively. The receiver operating characteristic curves (ROCs) of the traditional models are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. Among the 4 traditional models, the best discrimination ability was shown by the model constructed by the GBM method. After adding the PGGRS, the AUCs of the models were increased by 0.001, 0.008, 0.023, and 0.017 for the Cox, ANN, RF, and GBM methods, respectively. Except for the Cox methods, the increase in AUC of other methods showed significant differences, indicating that the discrimination of the traditional+PGGRS models was acceptable, especially in the case of the GBM method. The comparison of ROCs between the traditional model and the traditional+PGGRS model is shown in Fig. 1.

The IDI and continuous NRI are provided in Table 3, and they were used to examine whether adding the PGGRS to the traditional model could improve the reclassification ability. The results showed that the risk of incident hypertension reclassification was significantly improved by the PGGRS for all four methods. The PGGRS increase the IDI by 1.39% (0.60–2.26%), 2.86% (0.72–5.33%), 4.73% (2.99–6.35%), and 4.68% (2.03–7.81%) and the NRI by 25.05% (14.87%, 36.00%), 13.01% (−16.90–30.99%), 44.87% (32.04–53.39%), and 22.94% (8.22%, 37.13%) for the Cox, ANN, RF, and GBM methods, respectively. These results represented a significant improvement in reclassification resulting from the addition of the PGGRS for predicting incident hypertension.

The decision curve was plotted for the measurement of the impact of using the PGGRS for predicting incident hypertension, which is shown in Fig. 2. Compared with all hypertensive patients with or without intervention, in the interval with a threshold probability lower than 80%, the model with the PGGRS had a higher net benefit for the RF and GBM methods; for the ANN method, the traditional+PGGRS model had a higher net benefit when the threshold probability was less than 45%. Such a curvilinear trend suggested that the traditional models had better benefits when combined with the PGGRS.

Decision curve of models. The “None” line means that none of the participants had hypertension or were undergoing any intervention; the “All” line represents that all participants had hypertension and all received the intervention. Cox Cox regression, ANN artificial neural network, RF random forest, GBM gradient boosting machine

Sensitivity analysis

Whether adding the SGRS and DLGRS could improve the predictive ability of the traditional models was also analyzed, although the SGRS and DLGRS were not significantly related to incident hypertension after adjusting for baseline blood pressure (Supplementary Fig. 2). The results are shown in Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. In summary, adding the SGRS partially improved the discrimination and reclassification of the traditional model, especially using the RF method. The addition of the DLGRS resulted in significant AUC improvement for the ANN, RF, and GBM methods. The risk of incident hypertension was reclassified using Cox and RF methods. Similar results were observed for the SGRS, PGGRS, and DLGRS, which explained the role of genetic factors in the prediction of incident hypertension.

Discussion

Based on a rural cohort population, this study validated the predictive performance of the PGGRS, which was associated with incident hypertension irrespective of baseline blood pressure. The AUC, NRI, and IDI results showed that the discrimination of the traditional model significantly improved and that the ability to predict the risk of incident hypertension improved when the PGGRS was added. Models with genetic factors exhibited superior net benefit than those without genetic factors. Moreover, predicting incident hypertension using machine learning was more efficient. This study provides evidence and choices for the clinical application of genetic information for the prediction of incident hypertension using machine learning methods.

The results are consistent with previous studies indicating that age, vegetable and fruit intake, family history of hypertension, physical activity, and BMI are risk factors for hypertension [31,32,33]. In addition, smoking, alcohol consumption, and lipid levels were risk factors for hypertension, but the screening variable process in this study excluded them from the model. This may be due to the effect of these variables on hypertension becoming less significant over time or to racial differences in the different studies. In addition, the results of the present study showed that high levels of physical activity increase the risk of developing hypertension. This finding may be explained by the physical activity characteristics of rural people. A recent article suggested a physical activity paradox in which leisure time physical activity is a protective factor, whereas physical activity at work is a risk factor for adverse cardiovascular events [34]. Our study focused on a rural population whose physical activity occurs primarily at work. Therefore, our findings suggest that physical activity in rural populations is a risk factor for incident hypertension, which is consistent with previous studies and provides evidence for future studies related to physical activity.

This study calculated three GRSs based on 13 hypertension-related SNPs, and the relationship between GRSs and incident hypertension was determined (Supplementary Fig. 2). The results showed that the PGGRS was strongly associated with incident hypertension after adjustment for baseline blood pressure; for every 1-unit increase in PGGRS, the risk of incident hypertension increased 4.6%. Several previous studies have also reported the prominent association of GRSs with hypertension/blood pressure [35,36,37]. These similar results further confirmed that GRSs integrated with SNPs are related to hypertension.

A previous study conducted in Sweden stated that a GRS was independently associated with elevated blood pressure but was not useful for hypertension prediction when considered in terms of whether the AUC increased [8]. A subsequent study from Korea revealed similar but differential results,: the AUC increased by 0.001 (P = 0.1057) when the GRS was added, but the reclassification of the model increased due to the addition of the GRS [9]. To explain whether the addition of the GRS can improve the performance of the predictive model, especially in resource-limited settings, this study established a traditional model and then added the PGGRS to examine the effect of genetic factors in predicting incident hypertension in the rural population with 3-year follow-up data. With the addition of the PGGRS, the increases in AUC were significant for all three machine learning methods, and the NRI and IDI were significantly improved, suggesting considerable improvement in terms of discrimination and reclassification, respectively. A large-scale population study proposed a parallel improvement in prediction model performance [10]. The results of SGRS and DLGRS also partially indicated the same conclusion. Models incorporating the GRS could better predict incident hypertension, indicating the feasibility of using genetic information to predict hypertension over time.

The decision curve of the traditional model and traditional+PGGRS model showed that models with the PGGRS had better net benefits than those that only contained traditional factors. A previous study argued that genetic information could be contained in a prediction model for the assessment of cardiovascular disease risk, thus lowering the level of LDL-C in patients [38]. Our results regarding the decision curve resulted in a similar inference, suggesting that genetic information plays a potential role in clinical disease prevention and decision-making.

Notably, the traditional statistical method (Cox regression) and three machine learning algorithms (ANN, RF, GBM) were adopted to construct the prediction model. According to our results, the better method to predict the risk of hypertensive events using genetic factors was machine learning, and the AUCs of the ANN, RF, and GBM methods with the addition of the PGGRS were 0.798, 0.861, and 0.871, respectively. This result demonstrates that using machine learning methods to utilize genetic factors for hypertension prediction is effective and can provide more options for clinical hypertension prediction. Moreover, the GBM exhibited outstanding predictive ability for the risk identification of incident hypertension. Other studies also indicated the critical role of boosting algorithms in diverse diseases [12, 39,40,41]. These findings may be explained by the fact that machine learning can better manage the complicated and indivisible relationships among risk factors.

This research, conducted in a rural Chinese cohort, can better demonstrate the causal relationship between variables and outcomes, thus better demonstrating the effect of genetic factors on incident hypertension prediction in resource-limited areas. In addition, the machine learning methods were used to build the model to maximize the utilization of data. Nonetheless, several limitations need to be concerned. First, this study only verified the results of the analysis in the same population that was randomly divided into a train dataset and a test dataset, which may interfere with the extrapolation of the conclusion. Second, the 3-year follow-up may be insufficient to account for the long-term impact of genetic factors on the development of hypertension, and the results should be confirmed in subsequent studies in our cohort or in other cohort studies with longer follow-up durations. Third, only 13 hypertension-related SNPs were detected and included in the GRS, and the possible interaction between genetic variants and environmental factors was not considered; consequently, the effect of genetic information in predicting hypertension may not have been fully discovered.

Conclusion

To what extent genetic elements affect incident hypertension was previously undetermined, peculiarly in areas with limited resources. Based on a rural prospective study conducted in China, the present study found a significant relationship of genetic elements with incident hypertension. In addition, the addition of the PGGRS resulted in more significant improvements to the traditional model both in terms of discrimination and reclassification, while the use of machine learning methods could result in even more improvements. The results suggested the potential clinical use of genetic elements in predicting incident hypertension leveraging machine learning techniques.

References

Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134:441–50.

Lawes CMM, Vander Hoorn S, Rodgers A, Hypertens IS. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet. 2008;371:1513–8.

Rapsomaniki E, Timmis A, George J, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Shah AD, Denaxas S, et al. Blood pressure and incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: Lifetime risks, healthy life-years lost, and age-specific associations in 1·25 million people. Lancet. 2014;383:1899–911.

Levy D, Ehret GB, Rice K, Verwoert GC, Launer LJ, Dehghan A, et al. Genome-wide association study of blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Genet. 2009;41:677–87.

Evangelou E, Warren HR, Mosen-Ansorena D, Mifsud B, Pazoki R, Gao H, et al. Genetic analysis of over 1 million people identifies 535 new loci associated with blood pressure traits. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1412–25.

International Consortium for Blood Pressure Genome-Wide Association S, Ehret GB, Munroe PB, Rice KM, Bochud M, Johnson AD, et al. Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature. 2011;478:103–9.

Li C, Sun D, Liu J, Li M, Zhang B, Liu Y, et al. A prediction model of essential hypertension based on genetic and environmental risk factors in Northern Han Chinese. Int J Med Sci. 2019;16:793–9.

Fava C, Sjogren M, Montagnana M, Danese E, Almgren P, Engstrom G, et al. Prediction of blood pressure changes over time and incidence of hypertension by a genetic risk score in Swedes. Hypertension. 2013;61:319–26.

Lim NK, Lee JY, Lee JY, Park HY, Cho MC. The role of genetic risk score in predicting the risk of hypertension in the Korean population: Korean genome and epidemiology study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131603.

Lu X, Huang J, Wang L, Chen S, Yang X, Li J, et al. Genetic predisposition to higher blood pressure increases risk of incident hypertension and cardiovascular diseases in Chinese. Hypertension. 2015;66:786–92.

Deo RC. Machine learning in medicine. Circulation. 2015;132:1920–30.

Zhang L, Wang Y, Niu M, Wang C, Wang Z. Machine learning for characterizing risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in a rural Chinese population: the Henan Rural Cohort Study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4406.

Heo J, Yoon JG, Park H, Kim YD, Nam HS, Heo JH. Machine learning-based model for prediction of outcomes in acute. Stroke Stroke. 2019;50:1263–5.

Zhang L, Wang Y, Niu M, Wang C, Wang Z. Nonlaboratory-based risk assessment model for type 2 diabetes mellitus screening in Chinese rural population: a joint bagging-boosting model. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2021.3077114. Online ahead of print.

Liu X, Mao Z, Li Y, Wu W, Zhang X, Huo W, et al. Cohort Profile: The Henan Rural Cohort: a prospective study of chronic non-communicable diseases. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48:1756–1756j.

Liu LS, Hypertension WGoCGftMo. 2010 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Chin J Cardiol. 2011;39:579–615.

Kato N, Takeuchi F, Tabara Y, Kelly TN, Go MJ, Sim X, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies common variants associated with blood pressure variation in east Asians. Nat Genet. 2011;43:531–8.

Kato N, Loh M, Takeuchi F, Verweij N, Wang X, Zhang W, et al. Trans-ancestry genome-wide association study identifies 12 genetic loci influencing blood pressure and implicates a role for DNA methylation. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1282–93.

Lu X, Wang L, Lin X, Huang J, Charles Gu C, He M, et al. Genome-wide association study in Chinese identifies novel loci for blood pressure and hypertension. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:865–74.

Hong KW, Go MJ, Jin HS, Lim JE, Lee JY, Han BG, et al. Genetic variations in ATP2B1, CSK, ARSG and CSMD1 loci are related to blood pressure and/or hypertension in two Korean cohorts. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:367–72.

He J, Kelly TN, Zhao Q, Li H, Huang J, Wang L, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 8 novel loci associated with blood pressure responses to interventions in Han Chinese. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;6:598–607.

Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc Ser. 1972;34:187–202.

Bishop CM. Neural networks for pattern recognition. Oxford; Oxford University: 1996.

Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45:5–32.

Friedman J. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann Stat. 2001;29:1189–232.

Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KG. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ. 2015;350:g7594.

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36.

Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr., D’Agostino RB Jr., Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157–72.

Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr., Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med. 2011;30:11–21.

Kerr KF, Brown MD, Zhu K, Janes H. Assessing the clinical impact of risk prediction models with decision curves: guidance for correct interpretation and appropriate use. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2534–40.

Forman JP, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Diet and lifestyle risk factors associated with incident hypertension in women. JAMA. 2009;302:401–11.

Kaur P, Rao SR, Radhakrishnan E, Rajasekar D, Gupte MD. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, control and risk factors for hypertension in a rural population in South India. Int J Public Health. 2012;57:87–94.

Liu MW, Yu HJ, Yuan S, Song Y, Tang BW, Cao ZK, et al. Association between fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of hypertension among Chinese adults: a longitudinal study. Eur J Nutr. 2018;57:2639–47.

Holtermann A, Schnohr P, Nordestgaard BG, Marott JL. The physical activity paradox in cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: the contemporary Copenhagen General Population Study with 104 046 adults. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:1499–511.

Niiranen TJ, Havulinna AS, Langen VL, Salomaa V, Jula AM. Prediction of blood pressure and blood pressure change with a genetic risk score. J Clin Hypertens. 2016;18:181–6.

Oikonen M, Tikkanen E, Juhola J, Tuovinen T, Seppala I, Juonala M, et al. Genetic variants and blood pressure in a population-based cohort: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns study. Hypertension. 2011;58:1079–85.

Taal HR, Verwoert GC, Demirkan A, Janssens AC, Rice K, Ehret G, et al. Genome-wide profiling of blood pressure in adults and children. Hypertension. 2012;59:241–7.

Kullo IJ, Jouni H, Austin EE, Brown SA, Kruisselbrink TM, Isseh IN, et al. Incorporating a genetic risk score into coronary heart disease risk estimates: effect on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels (the MI-GENES clinical trial). Circulation. 2016;133:1181–8.

Taylor RA, Moore CL, Cheung KH, Brandt C. Predicting urinary tract infections in the emergency department with machine learning. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194085.

Sato M, Morimoto K, Kajihara S, Tateishi R, Shiina S, Koike K, et al. Machine-learning approach for the development of a novel predictive model for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7704.

Kruse C, Eiken P, Vestergaard P. Machine learning principles can improve hip fracture prediction. Calcif Tissue Int. 2017;100:348–60.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants, coordinators, and administrators for their support and help during the research.

Funding

This research was supported by the Henan Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No: 182300410293), Foundation of National Key Program of Research and Development of China (Grant no: 2016YFC0900803, 2019YFC1710002), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no: 81573243, 81602925), Foundation of Medical Science and Technology of Henan Province (No: 201702367, 2017T02098), and the Discipline Key Research and Development Program of Zhengzhou University (Grant no: XKZDQY202008, XKZDQY202002). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, M., Wang, Y., Zhang, L. et al. Identifying the predictive effectiveness of a genetic risk score for incident hypertension using machine learning methods among populations in rural China. Hypertens Res 44, 1483–1491 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00738-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00738-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Predicting survival factor following suicide attempt in Iran: an ensemble machine learning technique

BMC Psychiatry (2025)

-

Explainable AI in action: a comparative analysis of hypertension risk factors using SHAP and LIME

Neural Computing and Applications (2025)

-

Development of risk models of incident hypertension using machine learning on the HUNT study data

Scientific Reports (2024)