Abstract

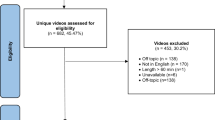

The objective of the current study was to evaluate the quality of the information provided in YouTubeTM videos on phimosis. The term “phimosis” was searched on YouTubeTM, and the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) for Audio/Visual Materials (Understandability and Actionability sections, good-quality score of minimum 70%) and misinformation scale (rated from 1 to 5) were used to assess video quality. Quality assessment was investigated over time. Of all, 60 were eligible for analysis. Healthcare providers were the authors of 75.0% of the videos, and 73.3% of the videos were patient-targeted. The median Understandability score was 42.9% (interquartile range [IQR]:34.5–58.9) and ranged from 28.6 to 42.9% (2013–2020). The median Actionability score was 50.0% (IQR:25.0–56.2) and ranged from 25.0 to 50.0% (2013–2020). The median misinformation score was 2.8/5 (IQR:1.6–3.6), and although the score fluctuated over time, the median score was 2.6 both in 2013 and in 2020. According to our results, although an increase of PEMAT over time was observed, the overall quality of the information uploaded on YouTubeTM is low. Therefore, at present, YouTubeTM cannot be recommended as a reliable source of information on phimosis. Video producers should upload higher-quality videos to help physicians and patients in the decision-making process.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data and materials are available whenever requested.

Code availability

Code is available whenever requested.

References

Salonia A, Bettocchi C, Boeri L, Capogrosso P, Carvalho J, Cilesiz NC, et al. European association of urology guidelines on sexual and reproductive health—2021 update: male sexual dysfunction. Eur Urol. 2021;80:333–57.

Hayashi Y, Kojima Y, Mizuno K, Kohri K. Prepuce: phimosis, paraphimosis, and circumcision. Sci World J. 2011;11:289–301.

McGregor TB, Pike JG, Leonard MP. Pathologic and physiologic phimosis: approach to the phimotic foreskin. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2007;53:445–8.

Morris BJ, Matthews JG, Krieger JN. Prevalence of phimosis in males of all ages: systematic review. Urology. 2020;135:124–32.

Balasubramanian A, Yu J, Srivatsav A, Spitz A, Eisenberg ML, Thirumavalavan N, et al. A review of the evolving landscape between the consumer Internet and men’s health. Transl Androl Urol. 2020;9:S123–34.

Bujnowska-Fedak MM, Waligóra J, Mastalerz-Migas A. The internet as a source of health information and services. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1211:1–16.

Gómez Rivas J, Carrion DM, Tortolero L, Veneziano D, Esperto F, Greco F, et al. Scientific social media, a new way to expand knowledge. What do urologists need to know? Actas Urol Esp. 2019;43:269–76.

Teoh JY-C, Ong WLK, Gonzalez-Padilla D, Castellani D, Dubin JM, Esperto F, et al. A global survey on the impact of COVID-19 on urological services. Eur Urol. 2020;78:265–75.

Creta M, Sagnelli C, Celentano G, Napolitano L, La Rocca R, Capece M, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection affects the lower urinary tract and male genital system: A systematic review. J Med Virol. 2021;93:3133–42.

YouTube for Press [Internet]. [cited 2021 Mar 7]. Available from: https://blog.youtube/press

Loeb S, Sengupta S, Butaney M, Macaluso JN, Czarniecki SW, Robbins R, et al. Dissemination of misinformative and biased information about prostate cancer on YouTube. Eur Urol. 2019;75:564–7.

Social media demographics to inform your brand’s strategy in 2021 [Internet]. Sprout Social. 2021 [cited 2021 Mar 25]. Available from: https://sproutsocial.com/insights/new-social-media-demographics/

Gul M, Diri MA. YouTube as a source of information about premature ejaculation treatment. J Sex Med. 2019;16:1734–40.

Fode M, Nolsøe AB, Jacobsen FM, Russo GI, Østergren PB, Jensen CFS, et al. Quality of information in YouTube videos on erectile dysfunction. Sex Med. 2020;8:408–13.

Ku S, Balasubramanian A, Yu J, Srivatsav A, Gondokusumo J, Tatem AJ, et al. A systematic evaluation of youtube as an information source for male infertility. Int J Impot Res. 2021;33:611–5.

Szmuda T, Rosvall P, Hetzger TV, Ali S, Słoniewski P. YouTube as a source of patient information for hydrocephalus: a content-quality and optimization analysis. World Neurosurg. 2020;138:e469–77.

Ward M, Ward B, Abraham M, Nicheporuck A, Elkattawy O, Herschman Y, et al. The educational quality of neurosurgical resources on YouTube. World Neurosurg. 2019;130:e660–5.

Gerundo G, Collà Ruvolo C, Puzone B, Califano G, La Rocca R, Parisi V, et al. Personal protective equipment in Covid-19: Evidence-based quality and analysis of YouTube videos after one year of pandemic. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50:300–5.

Megaly M, Khalil C, Tadros B, Tawadros M. Evaluation of educational value of YouTube videos for patients with coeliac disease. Int J Celiac Dis. 2016;4:102–4.

The Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) and User’s Guide. :67.

Shoemaker SJ, Wolf MS, Brach C. Development of the patient education materials assessment tool (PEMAT): A new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96:395–403.

Betschart P, Pratsinis M, Müllhaupt G, Rechner R, Herrmann TR, Gratzke C, et al. Information on surgical treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia on YouTube is highly biased and misleading: Surgical treatment of BPH on YouTube. BJU Int. 2020;125:595–601.

Phimosis - Patient Information [Internet]. [cited 2021 Mar 5]. Available from: https://patients.uroweb.org/other-diseases/phimosis/

Natali A, Rossetti MA. Complications of self‐circumcision: a case report and proposal. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2970–2.

Kintu-Luwaga R. The emerging trend of self-circumcision and the need to define cause: Case report of a 21 year-old male. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;25:225–8.

Ettanji A, Bencherki Y, Wichou EM, Dakir M, Debbagh A, Aboutaieb R. Foreskin necrosis – Complication following self-circumcision. Urol Case Rep. 2021;38:101671.

Montes Cardona CE, García-Perdomo HA. Incidence of penile cancer worldwide: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Panam Salud Pública. 2017;41:e117.

Survival Rates for Penile Cancer [Internet]. [cited 2021 Dec 20]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/penile-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html.

Thomas A, Necchi A, Muneer A, Tobias-Machado M, Tran ATH, Van Rompuy A-S, et al. Penile cancer. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2021;7:11.

Salama A, Panoch J, Bandali E, Carroll A, Wiehe S, Downs S, et al. Consulting “Dr. YouTube”: an objective evaluation of hypospadias videos on a popular video-sharing website. J Pediatr Urol. 2020;16:70.e1–e9.

Rubel KE, Alwani MM, Nwosu OI, Bandali EH, Shipchandler TZ, Illing EA, et al. Understandability and actionability of audiovisual patient education materials on sinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020;10:564–71.

Duran MB, Kizilkan Y. Quality analysis of testicular cancer videos on YouTube. Andrologia. 2021 ;53:e14118.

Pratsinis M, Abt D, Müllhaupt G, Langenauer J, Knoll T, Schmid H-P, et al. Systematic assessment of information about surgical urinary stone treatment on YouTube. World J Urol. 2021;39:935–42.

Capece M, Di Giovanni A, Cirigliano L, Napolitano L, La Rocca R, Creta M, et al. YouTube as a source of information on penile prosthesis. Andrologia. 2022;54:e14246.

Melchionna A, Collà Ruvolo C, Capece M, La Rocca R, Celentano G, Califano G, et al. Testicular pain and youtubeTM: are uploaded videos a reliable source to get information? Int J Impot Res. 2022 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-022-00536-w. Online ahead of print.

Morra S, Collà Ruvolo C, Napolitano L, La Rocca R, Celentano G, Califano G, et al. YouTubeTM as a source of information on bladder pain syndrome: A contemporary analysis. Neurourol Urodyn. 2022;41:237–45.

Baydilli N, Selvi I. Is social media reliable as a source of information on peyronie’s disease treatment? Int J Impot Res. 2021 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-021-00454-3. Online ahead of print.

Brimley S, Natale C, Dick B, Pastuszak A, Khera M, Baum N, et al. The emerging critical role of telemedicine in the urology clinic: a practical guide. Sex Med Rev. 2021;9:289–95.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Rachel C. Applefield, from the IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, for the English language revision of this paper. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: SC, CCR, MC, MC, RLR, GC, GC. Data acquisition: CT, SC, SM, AM. Analysis and interpretation of data: CCR, GC, FM. Drafting the manuscript: AP, CI, VM. Style revision: FC, PV. All authors revised the manuscript and read and approved the version submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The paper is exempt from ethical committee approval.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cilio, S., Collà Ruvolo, C., Turco, C. et al. Analysis of quality information provided by “Dr. YouTubeTM” on Phimosis. Int J Impot Res 35, 398–403 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-022-00557-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-022-00557-5

This article is cited by

-

Social Media and Men’s Health: Separating Science from Speculation in Andrology

Basic and Clinical Andrology (2025)

-

Post-finasteride syndrome - a true clinical entity?

International Journal of Impotence Research (2025)

-

Quality of information in Youtube videos on disorder of sexual development

International Journal of Impotence Research (2024)

-

YouTube™ as a source of information on prostatitis: a quality and reliability analysis

International Journal of Impotence Research (2024)

-

The spreading information of YouTube videos on Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors: a worrisome picture from one of the most consulted internet source

International Journal of Impotence Research (2024)