Abstract

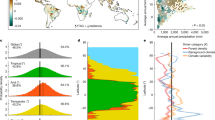

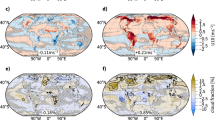

Climate-driven forest mortality events have been extensively observed in recent decades, prompting the question of how quickly these affected forests can recover their functionality following such events. Here we assessed forest recovery in vegetation greenness (normalized difference vegetation index) and canopy water content (normalized difference infrared index) for 1,699 well-documented forest mortality events across 1,600 sites worldwide. By analysing 158,427 Landsat surface reflectance images sampled from these sites, we provided a global assessment on the time required for impacted forests to return to their pre-mortality state (recovery time). Our findings reveal a consistent decline in global forest recovery rate over the past decades indicated by both greenness and canopy water content. This decline is particularly noticeable since the 1990s. Further analysis on underlying mechanisms suggests that this reduction in global forest recovery rates is primarily associated with rising temperatures and increased water scarcity, while the escalation in the severity of forest mortality contributes only partially to this reduction. Moreover, our global-scale analysis reveals that the recovery of forest canopy water content lags significantly behind that of vegetation greenness, implying that vegetation indices based solely on greenness can overestimate post-mortality recovery rates globally. Our findings underscore the increasing vulnerability of forest ecosystems to future warming and water insufficiency, accentuating the need to prioritize forest conservation and restoration as an integral component of efforts to mitigate climate change impacts.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The tree mortality sites are available at https://www.tree-mortality.net/globaltreemortalitydatabase/ (ref. 5), https://doi.org/10.3897/oneeco.4.e37753 (ref. 57) and https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151604 (ref. 58). These are summarized and available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28375442 (ref. 104). The original NDVI and NDII data are available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28375529 (ref. 105). The climate, vegetation and soil data are available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28375550 (ref. 106). The world continental boundaries were sourced from the Environmental Systems Research Institute World Continents dataset at https://hub.arcgis.com/datasets/esri::world-continents/about. The temperature and precipitation data can be retrieved from https://data.ceda.ac.uk/badc/cru/data/cru_ts. The SPEI data are available at https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/202305. The available water storage capacity, CEC, soil bulk density, soil clay and soil pH data were downloaded from https://daac.ornl.gov/SOILS/guides/HWSD.html. The STN can be obtained from https://data.isric.org/. The canopy height can be retrieved from https://webmap.ornl.gov/ogc/dataset.jsp?dg_id=10023_1. The global maximum rooting depth was derived from the Global Earth Observation for Integrated Water Resource Assessment (Earth2Observe) dataset available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12047241.v6 (ref. 107). The tree density was derived from https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_fes_data/1/. The forest age data were downloaded from https://doi.org/10.17871/ForestAgeBGI.2021. The SLA data were downloaded from https://www.try-db.org/. The forest biomes were classified as DBF, ENF and shrubland based on the European Space Agency/Climate Change Initiative Land Cover (http://maps.elie.ucl.ac.be/CCI/viewer/). The LAI was obtained from MOD15A2H.061 (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod15a2hv061/).

Code availability

Java, MATLAB and Python Codes for the analysis of these data are available via GitHub at https://github.com/YCY-github-YCY/Forest (ref. 108). The Landsat-based NDVI and NDII, and digital elevation model (including elevation, slope and aspect) are calculated on GEE, which is available at https://code.earthengine.google.com/.

References

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global carbon budget 2023. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 5301–5369 (2023).

Reid, W. V. et al. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis: A Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Island, 2005).

Allen, C. D. et al. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 259, 660–684 (2010).

Allen, C. D., Breshears, D. D. & McDowell, N. G. On underestimation of global vulnerability to tree mortality and forest die‐off from hotter drought in the Anthropocene. Ecosphere https://doi.org/10.1890/ES15-00203.1 (2015).

Hammond, W. M. et al. Global field observations of tree die-off reveal hotter-drought fingerprint for Earth’s forests. Nat. Commun. 13, 1761 (2022).

Hartmann, H. et al. Research frontiers for improving our understanding of drought‐induced tree and forest mortality. New Phytol. 218, 15–28 (2018).

Liu, Q. et al. Drought‐induced increase in tree mortality and corresponding decrease in the carbon sink capacity of Canada’s boreal forests from 1970 to 2020. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 2274–2285 (2023).

McDowell, N. G. et al. Pervasive shifts in forest dynamics in a changing world. Science 368, eaaz9463 (2020).

Park Williams, A. et al. Temperature as a potent driver of regional forest drought stress and tree mortality. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 292–297 (2013).

Ratajczak, Z. et al. Abrupt change in ecological systems: inference and diagnosis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 33, 513–526 (2018).

Reyer, C. P. et al. Forest resilience and tipping points at different spatio‐temporal scales: approaches and challenges. J. Ecol. 103, 5–15 (2015).

Smith, T., Traxl, D. & Boers, N. Empirical evidence for recent global shifts in vegetation resilience. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 477–484 (2022).

Wu, D. et al. Reduced ecosystem resilience quantifies fine‐scale heterogeneity in tropical forest mortality responses to drought. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 2081–2094 (2022).

Portmann, R. et al. Global forestation and deforestation affect remote climate via adjusted atmosphere and ocean circulation. Nat. Commun. 13, 5569 (2022).

Unger, N. Human land-use-driven reduction of forest volatiles cools global climate. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 907–910 (2014).

Quinn Thomas, R., Canham, C. D., Weathers, K. C. & Goodale, C. L. Increased tree carbon storage in response to nitrogen deposition in the US. Nat. Geosci. 3, 13–17 (2010).

Zhu, Z. et al. Greening of the Earth and its drivers. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 791–795 (2016).

Adams, M. A., Buckley, T. N., Binkley, D., Neumann, M. & Turnbull, T. L. CO2, nitrogen deposition and a discontinuous climate response drive water use efficiency in global forests. Nat. Commun. 12, 5194 (2021).

Huxman, T. E. et al. Convergence across biomes to a common rain-use efficiency. Nature 429, 651–654 (2004).

Zhang, Y. et al. Increasing sensitivity of dryland vegetation greenness to precipitation due to rising atmospheric CO2. Nat. Commun. 13, 4875 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Parazoo, N. C., Williams, A. P., Zhou, S. & Gentine, P. Large and projected strengthening moisture limitation on end-of-season photosynthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9216–9222 (2020).

Tepley, A. J., Thompson, J. R., Epstein, H. E. & Anderson Teixeira, K. J. Vulnerability to forest loss through altered postfire recovery dynamics in a warming climate in the Klamath Mountains. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 4117–4132 (2017).

Peñuelas, J. et al. Shifting from a fertilization-dominated to a warming-dominated period. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1438–1445 (2017).

Joiner, J. et al. Global relationships among traditional reflectance vegetation indices (NDVI and NDII), evapotranspiration (ET), and soil moisture variability on weekly timescales. Remote Sens. Environ. 219, 339–352 (2018).

Liu, F. et al. Old‐growth forests show low canopy resilience to droughts at the southern edge of the taiga. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 2392–2402 (2021).

Yan, Y. et al. Climate-induced tree-mortality pulses are obscured by broad-scale and long-term greening. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 912–923 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Detecting post-fire burn severity and vegetation recovery using multitemporal remote sensing spectral indices and field-collected composite burn index data in a ponderosa pine forest. Int. J. Remote Sens. 32, 7905–7927 (2011).

Hislop, S. et al. Using Landsat spectral indices in time-series to assess wildfire disturbance and recovery. Remote Sens. 10, 460 (2018).

Pickell, P. D., Hermosilla, T., Frazier, R. J., Coops, N. C. & Wulder, M. A. Forest recovery trends derived from Landsat time series for North American boreal forests. Int. J. Remote Sens. 37, 138–149 (2016).

Khoury, S. & Coomes, D. A. Resilience of Spanish forests to recent droughts and climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 7079–7098 (2020).

Fan, L. et al. Siberian carbon sink reduced by forest disturbances. Nat. Geosci. 16, 56–62 (2023).

Larjavaara, M., Berninger, F., Palviainen, M., Prokushkin, A. & Wallenius, T. Post-fire carbon and nitrogen accumulation and succession in Central Siberia. Sci. Rep. 7, 12776 (2017).

Berner, L. T. et al. Cajander larch (Larix cajanderi) biomass distribution, fire regime and post-fire recovery in northeastern Siberia. Biogeosciences 9, 3943–3959 (2012).

Zhang, X., Yu, P., Wang, D. & Xu, Z. Density-and age-dependent influences of droughts and intrinsic water use efficiency on growth in temperate plantations. Agric. For. Meteorol. 325, 109134 (2022).

Boulton, C. A., Lenton, T. M. & Boers, N. Pronounced loss of Amazon rainforest resilience since the early 2000s. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 271–278 (2022).

Verbesselt, J. et al. Remotely sensed resilience of tropical forests. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 1028–1031 (2016).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proc. 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2016).

Lundberg, S. & Lee, S. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proc. 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’17) (eds von Luxburg, U. et al.) 4768–4777 (Curran Associates, 2017).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67 (2020).

Bolker, B. M. et al. Generalized linear mixed models: a practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 127–135 (2009).

Corlett, R. T. The impacts of droughts in tropical forests. Trends Plant Sci. 21, 584–593 (2016).

Nabuurs, G. et al. First signs of carbon sink saturation in European forest biomass. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 792–796 (2013).

Penuelas, J. Decreasing efficiency and slowdown of the increase in terrestrial carbon-sink activity. One Earth 6, 591–594 (2023).

Raupach, M. R. et al. The declining uptake rate of atmospheric CO2 by land and ocean sinks. Biogeosciences 11, 3453–3475 (2014).

Denissen, J. M. et al. Widespread shift from ecosystem energy to water limitation with climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 677–684 (2022).

Mason, R. E. et al. Evidence, causes, and consequences of declining nitrogen availability in terrestrial ecosystems. Science 376, eabh3767 (2022).

Penuelas, J. et al. Increasing atmospheric CO2 concentrations correlate with declining nutritional status of European forests. Commun. Biol. 3, 125 (2020).

Peñuelas, J. et al. Human-induced nitrogen–phosphorus imbalances alter natural and managed ecosystems across the globe. Nat. Commun. 4, 2934 (2013).

Wieder, W. R., Cleveland, C. C., Smith, W. K. & Todd-Brown, K. Future productivity and carbon storage limited by terrestrial nutrient availability. Nat. Geosci. 8, 441–444 (2015).

Turner, M. G. & Seidl, R. Novel disturbance regimes and ecological responses. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst 54, 63–83 (2023).

Zhang, F. et al. Attributing carbon changes in conterminous US forests to disturbance and non-disturbance factors from 1901 to 2010. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeo. 117, G02021 (2012).

Seidl, R. & Turner, M. G. Post-disturbance reorganization of forest ecosystems in a changing world. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2092777177 (2022).

Forzieri, G., Dakos, V., McDowell, N. G., Ramdane, A. & Cescatti, A. Emerging signals of declining forest resilience under climate change. Nature 608, 534–539 (2022).

Liu, Y., Kumar, M., Katul, G. G. & Porporato, A. Reduced resilience as an early warning signal of forest mortality. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 880–885 (2019).

Schuur, E. A. et al. The effect of permafrost thaw on old carbon release and net carbon exchange from tundra. Nature 459, 556–559 (2009).

Vogelmann, J. E., Gallant, A. L., Shi, H. & Zhu, Z. Perspectives on monitoring gradual change across the continuity of Landsat sensors using time-series data. Remote Sens. Environ. 185, 258–270 (2016).

Caudullo, G. & Barredo, J. I. A georeferenced dataset of drought and heat-induced tree mortality in Europe. One Ecosyst. 4, e37753 (2019).

Gazol, A. & Camarero, J. J. Compound climate events increase tree drought mortality across European forests. Sci. Total Environ. 816, 151604 (2022).

Klemas, V. & Smart, R. The influence of soil salinity, growth form, and leaf moisture on the spectral radiance of Spartina alterniflora canopies. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 49, 77–83 (1983).

Liu, F. et al. Remotely sensed birch forest resilience against climate change in the northern China forest-steppe ecotone. Ecol. Indic. 125, 107526 (2021).

Barta, K. A., Hais, M. & Heurich, M. Characterizing forest disturbance and recovery with thermal trajectories derived from Landsat time series data. Remote Sens. Environ. 282, 113274 (2022).

Viana-Soto, A. et al. Quantifying post-fire shifts in woody-vegetation cover composition in Mediterranean pine forests using Landsat time series and regression-based unmixing. Remote Sens. Environ. 281, 113239 (2022).

White, J. C., Hermosilla, T., Wulder, M. A. & Coops, N. C. Mapping, validating, and interpreting spatio-temporal trends in post-disturbance forest recovery. Remote Sens. Environ. 271, 112904 (2022).

White, J. C., Wulder, M. A., Hermosilla, T., Coops, N. C. & Hobart, G. W. A nationwide annual characterization of 25 years of forest disturbance and recovery for Canada using Landsat time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 194, 303–321 (2017).

Masek, J. G. et al. A Landsat surface reflectance dataset for North America, 1990–2000. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 3, 68–72 (2006).

Vermote, E. & Saleous, N. LEDAPS Surface Reflectance Product Description (University of Maryland, 2007).

Vermote, E., Justice, C., Claverie, M. & Franch, B. Preliminary analysis of the performance of the Landsat 8/OLI land surface reflectance product. Remote Sens. Environ. 185, 46–56 (2016).

Foga, S. et al. Cloud detection algorithm comparison and validation for operational Landsat data products. Remote Sens. Environ. 194, 379–390 (2017).

Peng, X. et al. Northern Hemisphere greening in association with warming permafrost. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeo. 125, e2019JG005086 (2020).

Piao, S. et al. Evidence for a weakening relationship between interannual temperature variability and northern vegetation activity. Nat. Commun. 5, 5018 (2014).

Wu, X. et al. Higher temperature variability reduces temperature sensitivity of vegetation growth in Northern Hemisphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 6173–6181 (2017).

Roy, D. P. et al. Characterization of Landsat-7 to Landsat-8 reflective wavelength and normalized difference vegetation index continuity. Remote Sens. Environ. 185, 57–70 (2016).

Amani, M. et al. Google Earth Engine cloud computing platform for remote sensing big data applications: a comprehensive review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 13, 5326–5350 (2020).

Gorelick, N. et al. Google Earth Engine: planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 202, 18–27 (2017).

Tamiminia, H. et al. Google Earth Engine for geo-big data applications: a meta-analysis and systematic review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 164, 152–170 (2020).

Yilmaz, M. T., Hunt, E. R. Jr & Jackson, T. J. Remote sensing of vegetation water content from equivalent water thickness using satellite imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 112, 2514–2522 (2008).

Baret, F., Jacquemoud, S., Guyot, G. & Leprieur, C. Modeled analysis of the biophysical nature of spectral shifts and comparison with information content of broad bands. Remote Sens. Environ. 41, 133–142 (1992).

Jacquemoud, S. et al. PROSPECT+ SAIL models: a review of use for vegetation characterization. Remote Sens. Environ. 113, S56–S66 (2009).

Zeng, Y. et al. Optical vegetation indices for monitoring terrestrial ecosystems globally. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 477–493 (2022).

Brodribb, T. J., Powers, J., Cochard, H. & Choat, B. Hanging by a thread? Forests and drought. Science 368, 261–266 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Widespread spring phenology effects on drought recovery of Northern Hemisphere ecosystems. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 182–188 (2023).

Schwalm, C. R. et al. Global patterns of drought recovery. Nature 548, 202–205 (2017).

Wang, L. Spring phenology alters vegetation drought recovery. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 123–124 (2023).

Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Beguería, S., López-Moreno, J. I., Angulo, M. & El Kenawy, A. A global 0.5 gridded dataset (1901–2006) of a multiscalar drought index considering the joint effects of precipitation and temperature. J. Hydrometeorol. 11, 1033–1043 (2010).

Tong, X. et al. Increased vegetation growth and carbon stock in China karst via ecological engineering. Nat. Sustain. 1, 44–50 (2018).

Harris, I., Jones, P., Osborn, T. & Lister, D. Updated high-resolution grids of monthly climatic observations—the CRU TS3. 10 Dataset. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 623–642 (2014).

Gessler, A., Schaub, M. & McDowell, N. G. The role of nutrients in drought‐induced tree mortality and recovery. New Phytol. 214, 513–520 (2017).

Xu, T. et al. Soil property plays a vital role in vegetation drought recovery in karst region of Southwest China. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeo. 126, e2021JG006544 (2021).

Yao, Y., Liu, Y., Zhou, S., Song, J. & Fu, B. Soil moisture determines the recovery time of ecosystems from drought. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 3562–3574 (2023).

Wieder, W. R., Boehnert, J., Bonan, G. B. & Langseth, M. Regridded Harmonized World Soil Database v1.2. (ORNL DAAC, 2014).

Batjes, N. H. Harmonized soil property values for broad-scale modelling (WISE30sec) with estimates of global soil carbon stocks. Geoderma 269, 61–68 (2016).

Choat, B. et al. Triggers of tree mortality under drought. Nature 558, 531–539 (2018).

Fang, O. & Zhang, Q. B. Tree resilience to drought increases in the Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 245–253 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Temporal trade-off between gymnosperm resistance and resilience increases forest sensitivity to extreme drought. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1075–1083 (2020).

Simard, M., Pinto, N., Fisher, J. B. & Baccini, A. Mapping forest canopy height globally with spaceborne lidar. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeo. 116, G04021 (2011).

Crowther, T. W. et al. Mapping tree density at a global scale. Nature 525, 201–205 (2015).

Besnard, S. et al. Mapping global forest age from forest inventories, biomass and climate data. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2021, 4881–4896 (2021).

Moreno-Martínez, Á. et al. A methodology to derive global maps of leaf traits using remote sensing and climate data. Remote Sens. Environ. 218, 69–88 (2018).

Gazol, A., Camarero, J. J., Anderegg, W. & Vicente Serrano, S. M. Impacts of droughts on the growth resilience of Northern Hemisphere forests. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 26, 166–176 (2017).

Schwartz, N. B., Budsock, A. M. & Uriarte, M. Fragmentation, forest structure, and topography modulate impacts of drought in a tropical forest landscape. Ecology 100, e02677 (2019).

Sturm, J., Santos, M. J., Schmid, B. & Damm, A. Satellite data reveal differential responses of Swiss forests to unprecedented 2018 drought. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 2956–2978 (2022).

Farr, T. G. et al. The shuttle radar topography mission. Rev. Geophys. 45, RG2004 (2007).

Gareth, J., Daniela, W., Trevor, H. & Robert, T. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R (Spinger, 2013).

Yan, Y. et al. Tree mortality sites. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28375442 (2025).

Yan, Y. et al. Recovery of NDVI and NDII. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28375529 (2025).

Yan, Y. et al. Influencing factors. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28375550 (2025).

Li, X. et al. Temporal trade-off between gymnosperm resistance and resilience increases forest sensitivity to extreme drought. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12047241.v6 (2020).

Yan, Y. et al. YCY-github-YCY/Forest. GitHub https://github.com/YCY-github-YCY/Forest (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research programme (2024QZKK0301) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41988101). A.C. acknowledges support from the US Geological Survey (G22AC00431) and the US Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture (2024-67019-42396). We thank J. Sun, Z. Zeng, Y. Guo and H. Zhuang for their technical assistance in performing PROSAIL model simulations. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the US Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.P. and A.C. designed the research. Y.Y. conducted all data processing, calculated RT and ran the model. S.H. and Y.Y. performed statistical analysis and drafted the figures. S.H. and Y.Y. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. W.M.H. collected the tree-mortality sites. Y.Y., S.H., A.C., J.P., S.M.M., C.D.A., W.M.H. and R.B.M. revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the design, methods and results and contributed to the text.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Reviewer recognition

Nature Plants thanks Daniel Kneeshaw and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–13 and Tables 1–7.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, Y., Hong, S., Chen, A. et al. Satellite-based evidence of recent decline in global forest recovery rate from tree mortality events. Nat. Plants 11, 731–742 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-01948-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-01948-4

This article is cited by

-

A national soil organic carbon density dataset (2010–2024) in China

Scientific Data (2025)