Abstract

Over the past 10,000 years, the development of civilization has been enabled by the domestication of plants and animals tailored to human needs. The Triticeae tribe, including barley and wheat, has emerged as one of the most important sources of staple foods worldwide. Here, comparing genomes of wheat and barley genotypes from around the world, we unveiled genomic footprints of convergent selection affecting genes involved in crop adaptation and productivity, as well as a lack of parallel selection for diverse genes delivering genetic diversity specific to particular geographic and associated environmental conditions. We demonstrate that studying convergent selection between crops can help to identify genes crucial for adaptation and sources of diversity for improving cultivated species—forming the basis of the proposed concept of inter-crop translational research for breeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Wheat and barley are founder crops of the agricultural revolution that began around 10,000 years ago. They remain among the world’s most important cereals today, with archaeological records revealing considerable spatial and temporal parallelism in their histories of cultivation1,2. Both crops were prominent components of the ‘Neolithic package’ that spread progressively out from the Fertile Crescent, passing across the Mediterranean, Balkans, Transcaucasia and the Iranian Plateau to encompass Europe, Central Asia and then the Far East and parts of Africa3, adapting to these new environments. While they differ in their end uses—wheat being primarily used for bread-making and barley for beer brewing and animal fodder—they are morphologically similar and genetically closely related (with only 8–12 million years of divergence)4,5. Their domesticated forms span several ploidy levels, with diploid barley (Hordeum vulgare; somatic chromosome number 2n = 2x = 14), tetraploid domesticated emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccon; 2n = 4x = 28; subgenomes BA), tetraploid durum wheat (T. durum; 2n = 4x = 28; BA) and hexaploid bread wheat (T. aestivum; 2n = 6x = 42; BAD)6. The finding that the key switch from shattering to indehiscent ears during domestication involved Btr (Brittle rachis) genes in both wheat and barley7 indicates that genetic convergence underlies parallelism in their histories. Convergent evolution in crop species has been demonstrated for a handful of genes related to yield, apical dominance or lack of branching, reduction of seed dormancy, bitterness and seed dispersal8,9, but the genetic signatures of domestication and adaptation common to wheat and barley have never been examined on a genome-wide scale. Here, we present a comparative analysis of the genetic architecture of wheat and barley populations, represented by phenotypic and exome-sequencing data for 672 and 679 seedbank accessions, respectively, with the aim of identifying and quantifying genetic convergence at the gene and nucleotide levels.

Results

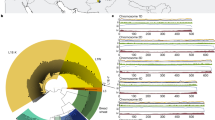

Our general strategy was to identify signatures of selection on a genome-wide scale separately for populations of four crops—barley (HV), domesticated emmer wheat (DEW), durum wheat (DW) and bread wheat (BW)—and subsequently to search for signs of convergence across genes with clear orthologous relationships. Although synteny between the studied genomes is strong10, identifying unambiguous orthologues between barley and the three subgenomes of polyploid wheat (A, B and D) is not trivial. We used an approach that identifies and validates orthologous relationships through ancestral genome reconstruction11. By comparing genes annotated on the reference genomes of barley, tetraploid and hexaploid wheats (cv. Morex, Svevo and Chinese Spring, respectively), we inferred the gene content of an ancestral Triticeae karyotype (ATK; Fig. 1a). The ATK established the karyotype backbone to trace the chromosome evolution of the modern Triticeae genomes over the past 8–12 million years (Supplementary Fig. 1) and provided orthogroups (OGs) used in our comparative population genomic analysis (Fig. 1b). We identified 32,833 genes on seven ATK protochromosomes, with various degrees of conservation across the extant (sub)genomes (Online Datasets). This set included 11,925 ‘perfectly conserved’ OGs, that is, groups of genes with one orthologous copy on each of the investigated (sub)genomes (one copy on each of barley, A and B of tetraploid wheat and A, B and D of hexaploid wheat). We also identified 7,328 ‘partially conserved’ OGs that were absent from some (sub)genomes or present in multiple copies (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

a, Scenario for evolution from the inferred grass (AGK, from Murat et al.11) and Triticeae (ATK) ancestors (top) into the extant genomes of rice, barley and wheats (bottom). The AGK of 7 protochromosomes (AGK7) evolved into 14 (AGK14) and 12 protochromosomes (AGK12), reaching the ATK of 7 protochromosomes (ATK7). Evolutionary events (fusions, fissions and translocations) are indicated on the modern karyotype as a mosaic of colours representing the ancestral chromosomes (AGK7), with polyploidization events indicated as red dots. b, A schematic diagram of the procedure used to detect convergent evolution involving the definition of conserved genes (OG, grey), conserved SNPs (orthoSNPs, black), concomitantly differentiated orthoSNPs (CD-orthoSNPs, red), HI variants (stop codon in the protein sequence, purple), conserved sweeps (orthoSweep, green) and conserved GWAS (orthoGWAS, blue) between barley (HV) and wheat (tetraploid emmer wheat (DEW), tetraploid durum wheat (DW) and hexaploid bread wheat (BW)) subpopulations (Subpop) (top) for conserved genes (grey rectangles). Indiv., individuals. Data integration, illustrated by a Venn diagram, highlights the identification of selection footprints impacting gene and protein function, as well as phenotypes, as a means of detecting convergent selection on genes underlying specific traits.

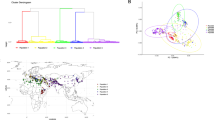

We compiled exome sequencing data for a total of 1,351 genotypes in barley12, tetraploid and bread wheats13, identifying 1,851k, 1,538k and 486k single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), respectively (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 and Online Datasets). Within these sets, we identified 375,901 ‘orthoSNPs’, that is, SNPs located within the perfectly or partially conserved OGs. In 39,032 cases, an orthologous nucleotide position was polymorphic in at least two of the three datasets (barley, hexaploid and tetraploid wheats), and we refer to these polymorphisms as ‘shared orthoSNPs’ (Supplementary Table 5 and Online Datasets). An inter-ploidy network summarizing the diversity of shared orthoSNPs separated the different subgenomes of polyploids, indicating non-concerted evolution. While the network reflects the role of tetraploid wheat as the progenitor of hexaploid wheat’s A and B subgenomes, it also suggests that the diversity across these two ploidy levels is largely independent (Fig. 2a). A population structure analysis based on species-specific SNP data identified nine populations of cultivated barley (HV_pop1–9), four populations of domesticated emmer wheat (DEW_pop3–6), four populations of durum wheat (DW_pop7-10) and six populations of bread wheat (BW_pop1–6). These designations are used throughout the text and figures hereafter. Wild barley, wild emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccoides) and GA-type tetraploids were treated as three ‘superpopulations’, with the last used in dedicated analyses described below (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 4). The identified populations reflect major phenotypic distinctions (for example two-row versus six-row barley; Supplementary Table 4) and the known routes of expansion of barley and wheat cultivation from their centres of origin13 (Fig. 2b). While our phylogenomic analysis of the A and B subgenomes suggests T. carthlicum (part of DW_pop7) as the sister group of hexaploid wheats (Fig. 2c), the topology is inconsistent when the subgenomes are separated (Supplementary Fig. 3). This suggests that gene flow between domesticated sympatric populations of bread wheat and BA tetraploids could be behind the origin of T. carthlicum14 and responsible for some diversity sharing across ploidy levels.

a, Network phylogenomics of 1,203 accessions of wheat (Triticum durum Td and Triticum aestivum Ta) and barley (Hv) with colours indicating the subgenomes of the species concerned (TdA and TdB for Triticum durum, TaA, TaB and TaD for Triticum aestivum). b, Left: Principal component analysis (PCA) of the genetic structure of wheat (tetraploid 4x, and hexaploid 6x) and barley genotypes, with a colour code illustrating the populations of the different species (ADM for admixed). For tetraploid wheat, GA-type population 1 is excluded for clarity, and emmer and durum wheats are assigned to 4 populations each: 3–6 and 7–10, respectively. Right: geographic locations of the different genotypes (dots) and inferred populations indicated as numbers in coloured circles at the geographic midpoint of each population. c, Phylogenetic analysis of tetraploid and hexaploid wheat accessions with a colour code identifying individual populations of tetraploid emmer wheat (DEW), tetraploid durum wheat (DW) and hexaploid bread wheat (BW), together with AGW (for wild AG-type wheat) and WEW (for wild emmer wheat), as indicated in the legend on the right.

We used the ATK-based perfectly conserved OGs and the above population datasets to identify signatures of convergent selection in barley and wheat. Per-population selective sweeps, that is, contiguous genomic regions displaying strong selection signals, were first defined, and the OG content of the sweeps was then determined and compared across multiple species (Fig. 1b). Selection signals were ascertained from three statistics: omega (detecting selection-related patterns of linkage disequilibrium (LD)); inter-population FST (scanning population differentiation across the genome); and θW*MAF (a metric combining Watterson’s theta with minor allele frequency (MAF)). As large parts of Triticeae genomes often display characteristics of selective sweeps that can also arise from neutral processes (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5), and some signals are overrepresented in particular genomic compartments (Supplementary Fig. 6), it is difficult to determine whether sweeps’ overlapping across species (orthoSweeps) occur by chance or correspond to genuine cases of parallel selection (Supplementary Fig. 7). We therefore used the concept of signal enrichment to quantify the extent of parallel selection. For OGs associated with selection signals of high intensity (measured as percentiles of the metric distribution) in two or more crops simultaneously, we calculated the ratio between observed cases and cases expected to arise by chance. Signal enrichment values greater than 1 indicate non-random sweep-sharing, probably due to parallel selection. When sharing of signals above the 95th percentile is summarized at the crop level (counting OGs swept in any population and on any subgenome of the polyploids), signal enrichment is statistically significant but low (Fig. 3a–c). Across OG members from different subgenomes of polyploid wheats (homeologs), we detected a dearth of signal sharing (Fig. 3d,e), suggesting that selection generally acts on a single member of a homeologous group. Considering the signal sharing on any or all subgenomes, we then calculated the signal enrichment for all pairwise combinations of wheat and barley populations for a range of percentile thresholds (0.6–0.999) (Supplementary Fig. 8). To ensure we did not focus on randomly overlapping orthoSweeps, we only considered inter-species population pairs with signal enrichment (excess of shared OGs) >20x, which yielded 22 orthoSweeps containing 451 OGs (Supplementary Table 6). We obtained comparable results when calculating the signal enrichment on individual OGs, and on entire swept regions, delivering 386 block-based sweeps included in the 451 gene-based sweeps (Supplementary Tables 7–9). The substantial excess of shared OGs in particular pairs of populations from different species strongly suggests convergent selection. This can be inferred not only for populations of wheat and barley, but also for populations of tetraploid and hexaploid wheats, despite their ancestor–descendant relationship. This is because here we do not track the sharing of haplotypes, but the sharing of selection signatures, which (unlike haplotypes) cannot pass across polyploidizations or occur via gene flow. It is also important to note that selection operates on genomic blocks, not on individual genes, and due to high LD in autogamous crops, selection signals do not normally allow to identify the real targets of selection. Nevertheless, all genes within a selective sweep are affected by selection (reducing their diversity in particular), and the real selection targets of orthoSweeps are more likely to be found among conserved OGs than among species-specific genes. Such comparative population genomics assessment thereby helps to narrow down the list of genes relevant for cultivation. Indeed, many of the 451 OGs we identified are associated with traits of importance for crop improvement and adaptation (see following sections), providing raw material for further research and being of potential use in breeding programmes.

a, For each of the four crops (HV, DEW, DW and BW), non-redundant sets of OGs with zc above the 95th percentile in any population (and any subgenome in the case of wheats) were extracted, and intersections of these sets were plotted in a Venn diagram. The numbers indicate the counts of unique OGs found in the corresponding fractions. b, Intersections of the four sets (HV, DW, DEW and BW on the Venn diagram to the left) generally contain more OGs than would be expected by chance. The expected number of OGs was calculated as \(\text{11,925}\times {\prod }_{i=1}^{n}\frac{{o}_{i}}{\text{11,925}}\), where oi is the observed number of OGs above the 95th percentile in the ith set. Intersections of two sets are associated with false discovery rate (FDR), the exact hypergeometric probability with normal approximation, adjusted by the Benjamini–Hochberg method. NA, not available. c, A Circos plot showing the zc statistics for selected populations of HV, DW, DEW and BW. OGs were located on barley chromosomes according to the coordinates of the barley orthogenes. For polyploid wheats, the maximum values for the two and three subgenomes were plotted. The highlights encircling the chromosomes indicate OGs above the 95th percentile in two (yellow), three (orange) or all four populations (red) indicated at the centre. d, A Venn diagram showing the numbers of OGs with zc above the 95th percentile in the A and B subgenomes of tetraploid wheat (means of all populations shown). e, A Venn diagram showing the numbers of orthogenes with zc above the 95th percentile in the A, B and D subgenomes of hexaploid wheat (means of all populations shown).

Alongside the sharing of selection signatures, we searched for signs of convergent selection on a single-nucleotide level, aiming to identify sequence convergence (homoplasy). For this purpose, we compiled orthoSNPs differentiated among populations of a single species (with allelic frequencies ≦0.1 and ≧0.9 in different populations), regarding such patterns as sign of within-species selection (Supplementary Tables 10 and 11). In total, 6,055, 6,551, 2,424 and 1,138 genes were found to contain 18,872, 20,756, 6,381 and 2,807 orthoSNPs differentiating domesticated populations of HV, DEW, DW and BW, respectively. Included genes are those implicated in grain weight or yield (GSN1, OsARF4, GL7, AN1, FLO2, SSG4, GSD1 and NOG1) and those involved in inflorescence development, spikelet architecture and tillering (OsARG, FUWA, DEP3, EP2, NAL1, D11, SGL1, OsGATA28 and IAA6). We then investigated whether differentiated orthoSNPs in the different species corresponded to the same geographic context (Fig. 4a,b). Most of the differentiated orthoSNPs involved locally adapted barley, emmer and durum-turgidum wheat from the Horn of Africa (Hv_pop4, DEW_pop6 and DW_pop7, respectively), and bread wheat (BW_pop3) with a distribution centred in Nepal (BW_pop3); Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 9). This is consistent with orthoSNP-based population differentiation (FST), indicating these environments impose strong selection pressures that shift allelic frequencies (Fig. 4a), with possible convergence in cases of sympatry and shared differentiated orthoSNPs between several populations of each species illustrating east–west expansion out of the centres of origin of barley and wheat cultivation (Fig. 4b).

a, The maps indicate orthoSNP-based genetic differentiation of the identified populations (pop), calculated as pairwise FST for each population and the union of the remaining populations. b, For each of the species (barley, as well as tetraploid and hexaploid wheats, indicated as 4x and 6x) and the corresponding populations (8, 8 and 6, respectively), geographically located (at the geographic midpoint of each population) pie charts illustrate the distribution of alleles (Alt for alternative in blue, Ref for reference in brown), with grey lines connecting top population pairs sharing the same alleles (see right legend). c, A Circos plot representation for each of the species (external circle) and associated populations (inner circle) and corresponding geographic location (intermediate circle) and number of CD-orthoSNPs (see colour code in the left legend) identified as common to species populations (centre). d, An UpsetR illustration of orthoSNPs common to populations of the four species (HV, DEW, DW and BW) with (CD-orthoSNPs, in blue on the left) and without (that is, species-species differentiated orthoSNPs, in red on the right) concomitant differentiation in the species investigated. e, World maps illustrating the distribution of alleles (Alt for alternative in red, Ref for Reference in blue) in barley, tetraploid and hexaploid wheats for a CD-orthoSNP identified as common to HV (HORVU.MOREX.r2.3HG0243700 gene), DEW (TRITD_3Av1G199050) and BW (TraesCS3A01G320100), encoding a purple acid phosphatase. f, Functional characterization of TdFUWA gene, with a schematic representation of the TdFUWA-A and TdFUWA-B homeologous genes, coloured fragments indicating the guide RNA position (left), and phenotypic differences in flowering time and growth rate (right).

Subsequently, we identified shared orthoSNPs that are concomitantly, that is, simultaneously, differentiated in at least two species (concomitantly differentiated orthoSNPs or CD-orthoSNPs) (Fig. 1b and Online Datasets). We take these potentially homoplasic SNPs from orthologous positions of OGs that have identical alternating nucleotides across species, as indicative of selection. We identified 88 CD-orthoSNPs common to 3 crops (2 between HV:DEW:DW, 1 between HV:DEW:BW and 85 between DEW:DW:BW) and 1,494 common to 2 crops (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Table 12 and Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10), with expected bias between subgenomes (B ≫ A > D; Supplementary Table 13). The single CD-orthoSNPs common to HV, DEW and BW are located in a purple acid phosphatase gene (PAP) and show a geographic pattern of differentiation that strongly overlaps across the three crops (Fig. 4d). The rice orthologue OsPAP10a, which is induced by phosphorus (P) starvation and improves ATP hydrolysis, has been proposed as a target for crop breeding to improve P use efficiency during growth and development15. It appears that particular haplotypes of the concomitantly differentiated PAP gene identified in our study have been simultaneously selected in barley, durum and bread wheat in particular environments, suggesting an adaptive value. In total, the 1,582 CD-orthoSNPs identified as common to at least two crops belonged to 948 non-redundant OGs (Supplementary Table 12 and Supplementary Fig. 10), with multiple homeologues of polyploids rarely involved—only four cases were observed, all in tetraploid wheat. These OGs include many genes involved in determining agronomic traits, such as EP2 and FUWA (involved in plant development and inflorescence architecture), SSG4 (regulation of starch grain size), IAA6 (control of tiller outgrowth), DRO1 (root system architecture and drought avoidance), GI (photoperiodic control of flowering and osmotic stress response), osDR11 (positive regulator of disease resistance), osGRAS23 (drought stress response), RSS1 (maintenance of meristem activity under stress conditions) and OsLCBK2 (regulation of disease resistance responses and programmed cell death).

To prove the concept that convergent signals of selection can be used to identify variation in agronomically important traits to be considered in breeding, we first dissected the functional role of FUWA, encoding an NHL repeat-containing protein16. By clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats–associated protein9 (CRISPR–Cas9) genome editing, we knocked out homeologues of TdFUWA-A and TdFUWA-B in the durum variety Svevo to create mutant lines ML1 and ML2 (Fig. 4f) for phenotypic analysis of the T3 generation (Supplementary Fig. 11). In standard growing conditions, ML1 and ML2 plants appeared shorter and flowered later than the wild-type Svevo plants, and they had shorter and narrower leaves. Interestingly, the difference in plant height was reduced at maturity and was insignificant at harvest, suggesting the influence of FUWA on growth rate rather than growth per se, or alternatively, its role is limited to the early stages of plant growth. Phenotypic analysis of BC1F2 generations indicated that mutations in both TdFUWA-A and TdFUWA-B were recessive, that is, the mutant phenotype is linked to the homozygous state. Based on our population-genetic data for tetraploid wheat, orthologues of FUWA with a G allele predominated in populations 3, 4, 5, 8, 9 and 10, while those with an A allele were more common in populations 1, 2, 6 and 7—revealing a clear north–south gradient in genetic variation (Fig. 4f). Moreover, haplotype analysis (haplotypes hereafter referred to with the prefix ‘H’ and a three-digit identifier from Supplementary Fig. 11) revealed a different allelic state at the TdFUWA-A locus and indicated differentiated distributions across both domestication status and geography: allelic state specific to wild AG-type wheat (4x_H005 and H008) and to WEW (4x_H006 and H009), and for the domesticated tetraploid wheat, haplotype states specific to the Horn of Africa (4x_H002 for DW and H004 for DEW) as well as Russia and North America (4x_H003 for DW) (Supplementary Fig. 11). A comparison between tetraploid and hexaploid wheats also indicated that the most abundant haplotype state at the FUWA-A locus in bread wheat (6x_H001) corresponds to the state fixed in durum-turgidum wheat sampled from the Horn of Africa, whereas the most widespread tetraploid wheat haplotype state (4x_H001) is rare in bread wheat (Supplementary Fig. 11). We then investigated the phenotypic role of the DEEPER ROOTING 1 (DRO1) gene in wheat. Identified in rice as affecting the angle at which the plant’s roots grow, which determines how deep the roots penetrate into soil and thereby the ability of the plant to access water17, DRO1 has been successfully manipulated in rice to breed new varieties with significantly higher grain yields under drought conditions18. In our current analysis, we focused only on the TdDRO1-B locus of tetraploid wheats, as the homoeologous gene for the A subgenome was not annotated for the applied reference genome. At first glance, and different to FUWA describe above, the identified haplotype states are not differentiated by domestication status nor geography, with the exception of 4x_H006 that is specific to AG-type wheat (Supplementary Fig. 11). However, a closer examination of 4x_H001 and H002 states in WEW showed that the former allelic state was present only in wild emmer originating from the Israel/Lebanon region, while all Turkish wild emmer accessions had the latter state. Although we were unable to collect phenotypic data on root growth angle for wild emmer accessions, the haplotype state 4x_H002 is also present in T. durum-turgidum wheat accessions from the Horn of Africa, and we were able to determine that it is associated with a significantly lower root growth angle than other haplotype states are (Supplementary Fig. 11). A comparison between tetraploid and hexaploid wheats indicated that the most abundant haplotype state at the DRO1-B locus in bread wheat (6x_H001) is also the most abundant state in DEW from Middle Eastern and Europe as well as in DW from Horn of Africa and in T. carthlicum (4x_H004, Supplementary Fig. 11).

Among the 1,582 CD-orthoSNPs common to at least two crops, 68 were common to barley and wheat (DW, DEW and/or BW) and 1,510 were shared only by wheat species (DW, DEW and BW) (Supplementary Table 12). As barley and wheat diverged some 8–12 million years ago and are separated by one or two polyploidization events causing extreme genetic bottlenecks, all of the 68 CD-orthoSNPs are extremely unlikely to be shared by descent. Instead, they can be regarded as cases of homoplasy and convergent selection. Conversely, the much more frequent CD-orthoSNPs common to DW-DEW and BW are more likely to be shared by descent, as BW is derived from tetraploid wheat, and subsequent gene flow has occurred. As a consequence, we cannot generally ascribe CD-orthoSNPs shared only among wheats to homoplasy, although there are a few clear cases (Supplementary Fig. 12). Regardless of whether these CD-orthoSNPs are shared by convergence or by descent, their strongly differentiated allelic frequencies (≦0.1 and ≧0.9 in different populations) within both tetraploid and hexaploid wheat clearly suggest that selection has operated on these loci at both ploidy levels. To investigate whether signatures of convergent selection between species corresponded to the same geographic context—implying adaptations to the same environment—we identified populations harbouring CD-orthoSNPs common to at least two species (Fig. 4c). Supporting this hypothesis of convergent adaptation, sympatric populations of barley and durum wheat from the Horn of Africa (Hv_pop4 and DW_pop7, respectively) share a large fraction of CD-orthoSNP variants. However, this was not the case for another wheat population (DEW_pop6) that overlapped in distribution, which instead shared most variants with the European barley population Hv_pop1. Across wheat ploidy levels, DEW_pop6 and DW_pop7 share a large fraction of CD-orthoSNPs with the Asian bread wheat population BW_pop3.

In addition to identifying signals indicative of parallel crop adaptation, we also considered signals related to domestication. Previous genetic studies have investigated genes targeted by domestication separately in different crop species19, but here we focus on polymorphisms selected in parallel during the domestication of different crops. We achieve this by utilizing orthoSNPs, first to identify polymorphisms separating wild (H. spontaneum for barley, T. dicoccoides for tetraploid wheats) and domesticated populations of the derived crop and subsequently intersecting these sets of orthoSNPs across different crops (Supplementary Table 14 and Supplementary Fig. 13). We identified 8, 182 and 446 orthoSNPs differentiated between the wild and all domesticated populations of HV, DW and DEW, respectively, indicative of species-specific ‘domestication switches’ (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15). The genes concerned are involved in seed germination, growth and development (BUI1, G11a and OsbZIP60), flowering (SPL7, TAF15b, S-locus, OsHAK26, Osnop, OsNTL5 and OsSPL15,), grain yield (HD3b, ARE1, OsMED15_2 and XIAO), inflorescence development (ES1, OsGAMYBL1, OsGAMYBL2 and OsSEU-2-3), starch synthesis (CDP3.2), seed germination and plant development (Gas2, SRD2 and Sweet1a). Among these domestication-related orthoSNPs, the sharing observed between DEW and DW (119) reflects both shared ancestry and domestication parallelism. Furthermore, 8,918, 7,781 and 6,228 orthoSNPs were differentiated between the wild species and at least one domesticated population of HV, DEW and DW, respectively. Most of these orthoSNPs were specific to a particular crop, although some were shared by crops (CD-orthoSNPs), with four common to HV, DEW and DW, three common to HV and DW, five common to HV and DEW and 2,095 common to DEW and DW (including 119 between wild and all DEW:DW domesticated populations) (Supplementary Table 14). As for signatures of convergent selection described above, the greater number of CD-orthoSNPs between DEW and DW may reflect both shared ancestry and domestication parallelism. Perhaps of greater current interest, the 12 domestication CD-orthoSNPs common to barley and various wheats included known genes such as RNP-1 (RNA-binding protein involved in cold adaptation), DCD (development and cell death involved in immune responses) and OMA1 (mitochondrial proteases involved in heat stress responses).

To investigate the functional impact of these convergent selection signals on biological processes, we classified all variants in species-specific datasets on the basis of their predicted impact on protein structure (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 15). The largest number of high-impact (HI) variants (probably leading to non-functional proteins) was found in tetraploid wheat (3,540 HI variants in 3,096 genes), followed by barley (1,996 in 1,601 genes) and then hexaploid wheat (1,281 in 1,188 genes) (Supplementary Fig. 16). Among the wheat subgenomes, B had the highest levels of HI variants, followed by A and then D (Fig. 5a). Within subgenomes, D had the highest proportion of HI variants among all variants identified (Fig. 5b). The HI variants identified consisted mostly of ‘stop-codon gained’ polymorphisms (>50% in any of the investigated crops) (Fig. 5c). Per population, the number of HI variants ranged from 299 (DW_pop10) to 1,051 (GA-type) for tetraploid wheat, from 240 (BW_pop3) to 398 (BW_pop6) for hexaploid wheat and from 172 (HV_pop8) to 273 (HV_pop5) for barley (Fig. 5d–f and Supplementary Tables 16 and 17). To assess the possible parallelism of HI variants across crops, we intersected the HI-variant datasets with the set of orthoSNPs. In total, 97 HI variants in 96 genes were identified as common to tetraploid and hexaploid wheats (Supplementary Table 18), including 57 (58.8%) and 9 (9.4%) that were monomorphic (that is, differentially fixed) in at least one tetraploid or hexaploid population, respectively. The genes harbouring these monomorphic variants included both a bHLH transcription factor with an ortholog in Arabidopsis (RHD6) essential for root hair development20 and an orthologue of Arabidopsis HYL1, mutations of which alter several growth-related traits21. Only one HI orthoSNP was found to be common to tetraploid wheat and barley, and none was common to hexaploid wheat and barley. With the set of 96 genes with HI variants shared among tetraploid and hexaploid wheats, and their identified orthologues in Arabidopsis, we searched the RARGE II database that provides information about Arabidopsis genes that significantly modify plant phenotypes when mutated. This led to the identification of a subset of 16 DW genes associated with major plant traits, 14 of which control seed traits, including seed size, length, number and width. Interestingly, ten of these genes were monomorphic in at least one tetraploid wheat population and one was monomorphic in bread wheat. The latter encodes a ubiquitin-like protein whose homologue mediates seedling growth and salt responses through the regulation of gibberellin metabolism in rice22.

a,b, Box plots showing, for barley and wheat (separated into subgenomes A, B and D on the x axis), the proportion of chromosomal HI-variants per megabase (a) and relative to the total number of variants (b, expressed in percentage on the y axis). c, HI-variant effects (x axis) and proportions (relative to the total number of variants, y axis) in each panel. d–f, Illustrations for each population of barley, tetraploid wheat and hexaploid wheat (y axis), of the number of HI variants (x axis) (d), the mean variant allele frequency (blue colour scale) calculated across all HI variants grouped by effect type, as defined from SnpEff annotation (e), and the functional enrichment significance (based on two q-value cut-offs) for the ‘defense response’ (GO:0006952) process across increasing variant allele frequencies (f). For box plots (a, b and d), boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), the line within each box indicates the median, and the whiskers extend to 1.5 × IQR; outliers are shown as individual points. g, Manhattan plot (top) of GWAS meta-analysis with indications of the major GWAS positions (and associated candidate genes in red) for HV and BW for heading date (HD), plant height (PH) and grain weight (GW) traits. The Venn diagrams (bottom) illustrate the number of conserved genes carrying SNPs significantly associated with those traits in GWAS.

To investigate the impact of previously reported variants conserved between species, we performed genome-wide association scans (GWAS) separately for three agronomic traits (heading date, plant height and grain weight) for barley and bread wheat (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 19). We performed a meta-analysis to identify significant marker–trait associations stable across environments according to the top 0.5% association P values or based on corrected P < 0.0001 thresholds (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 17). For plant height, we identified a total of 4,733 GWAS-based positions (top 0.05% of whole genome P-value distribution) for barley (with 2,063 peaks overlapping with OGs) and 2,039 for wheat (with 457 peaks within OGs). For heading date, we identified 5,076 GWAS-based positions for barley (with 2,450 peaks within OGs) and 2,009 for wheat (with 1,171 peaks within OGs), whereas for grain weight, we identified 4,634 such positions for barley (with 2,235 peaks within OGs) and 2,107 for wheat (with 1,415 peaks within OGs) (Supplementary Table 20). Some of the positions identified in the GWAS are located within genes known to be involved in the studied traits. For example, in barley, HvCEN Eps2/Eam6) and HvPPR37 (Ppd-H1) were identified for heading date, HvGA20ox2 (Sdw1) was identified for plant height, and HvTB1 (Int-C) for grain weight. In bread wheat, a peak was identified close to (at about 56 Mb) Ppd-B1 for heading date, and peaks were identified close to Rht-8 and Rht-B1 (at about 22 Mb and 31 Mb, respectively) for plant height. Comparing the positions identified by GWAS between species, we characterized 1, 106 and 25 OGs with GWAS signals common to wheat and barley for plant height, heading date and grain weight, respectively (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Table 21). Among these genes, Starch Branching Enzyme 4 is a candidate for grain weight, whereas Abscisic stress-ripening 2 and subunit 8 of the COP9 signalosome complex are relevant candidates for heading date. The shared signal for plant height lies in a gene encoding a DEAD-box ATP-dependent RNA helicase known to be involved in abiotic (salt) stress responses23.

In addition to signals of convergent selection, we identified crop-specific selection signals that do not suggest parallelism (299 in HV, 7,328 in DEW, 1,879 in DW and 1,118 in BW), that is, non-convergent selection (Fig. 4d). Over the 10,000 years of crop selection, it is unlikely that all favourable alleles were selected simultaneously in the different species. Thus, variants with signs of selection in a single species, for example, showing spatial differentiation along environmental gradients, may facilitate the identification of potentially useful variation in a related species that has not yet been exploited in breeding, that is, the translational research between crops for breeding, hereafter referred to as translational breeding. To demonstrate this concept of translational breeding, we identified crop-specific latitudinal differentiated orthoSNPs for each of the investigated crops, under the assumption that these may carry adaptive value in relation to environmental conditions such as photoperiod, heat and drought stress. This yielded a catalogue of 199 genes in HV, 15 shared between DEW and DW, and 373 in BW, showing a signal of non-convergent selection between species. The differentiated alleles suggest a potential interest—through breeding or genetic engineering—on the corresponding genes in the other crop, where those alleles have not yet been fixed or selected (Fig. 6a). One such southernmost differentiated orthoSNP in bread wheat (G/A polymorphism) is found within the orthologous OsMADS50 gene of rice that is involved in the regulation of flowering time24. This gene displays natural diversity, with the A variant of this orthoSNP possibly having an adaptive value in regulating flowering time in the absence of photoperiod changes, especially close to the Equator, where day length varies little across the year. Only the G allele was found in tetraploid wheat and barley. This means that, once functionally validated, the use of the A variant in genetic improvement of locally adapted varieties of tetraploid wheat and barley could be supported by facilitated genetic transfers and broader germplasm screening to identify it in potential (pre)breeding panels (Fig. 6a).

a, Top: world maps illustrating the northern and southern populations from which differentially fixed alleles were identified in barley, tetraploid (4x) or hexaploid (6x) wheats. Bottom: an illustrative example of alleles differentially fixed (G/A) between southern (Africa) and northern genotypes for a bread wheat gene (TraesCS4B01G346700) involved in the regulation of flowering time and not fixed (putatively transferable) in any barley or tetraploid wheat populations. Indiv, individual. b, Left: PCA illustration of the unique genetic diversity of the GA-type wheats (AGW) relative to BA-type populations (see colour code in the legend on the right). Right: illustration of GA introgression based on the mean allelic frequencies of AGW-specific variants (expressed as mean pd; see colour code in the legend on the right) calculated for each BA-type population in 5-Mb genomic windows for chromosomes 1A and 1B. c, A schematic illustration (top left) of archaeological sites around Lake Chalain (with Chalain site #19 in red) from which we obtained waterlogged samples of wheat dating back to 3200–3150 BC (bottom left), which we used for three-dimensional PCA (right) on the genetic diversity of extracted ancient DNA (aDNA) within the modern tetraploid wheats investigated as well as the Egyptian sample (‘EGY ANC’) reported by Scott et al.30 (see colour code in the legend on the left).

Promising cases for applying signals of non-convergent selection in translational breeding involve the GA-type wheat taxa described here that harbour unique genetic diversity in both population structure (see population 1 of tetraploid wheats in Fig. 6b) and in variant functionality25 (see GA-type Hi-variants in Fig. 5b). We therefore investigated the specific genetic diversity harboured by both modern and ancient (that is, the reported ‘new glume wheat’, referred to hereafter as NGW) GA-type Triticum to determine the genomic fraction that has potentially been integrated into bread wheat. The orthoSNPs that differentiated GA and WEW or DEW or DW, were 1,154, 1,486 and 3,161, respectively. In addition, the orthoSNPs that differentiated GA and both wild wheat and DW, or both WEW and DEW, or both DEW and DW, were 908, 1,508 and 2,589, respectively (Supplementary Table 22). Most of these orthoSNPs (39,359, that is, 78%) differentiated GA and all BA populations (that is, WEW, DEW and DW) investigated. These orthoSNPs, which may be considered as revealing GA diagnostic markers, highlight a relatively close relationship between WEW and GA-type wheats, with cultivated DW displaying greater divergence and contrasting allele fixation. We furthermore identified clear signals of GA introgression for several wheat populations based on mean allelic frequencies summarized over 5-Mb windows (Supplementary Fig. 18). The mean allelic frequency for GA-introgressed regions was highest on chromosome 1A, being especially high towards the end of the chromosome arm, particularly for the durum wheat populations of DW_pop8 (Middle East, Mediterranean and T. turanicum), DW_pop9 (Russia and North America) and DW_pop10 (Mediterranean) (Fig. 6b).

It has been suggested that GA-type wheats played an important role in the emergence of BA, and possibly of BAD wheats26 exploited in modern breeding. However, a presumed GA type of NGW was cultivated across western Asia and Europe during the Neolithic, apparently disappearing towards 1,000 BCE (ref. 27). We collected NGW from archaeological excavations at Lake Chalain (France), from a site located at an elevation of 500 msl on a western slope of the Jura mountains. The site, thought to correspond to 29 villages each spread over an area of 0.5–1 ha, was inhabited from 3,200 to 2,600 BCE (Fig. 6c). Automated morphometry analysis of spikelet remains revealed that the morphology of the NGW samples analysed was closer to T. timopheevii than to T. dicoccon (Supplementary Fig. 19). Shotgun sequencing of four double-indexed DNA libraries corresponding to 40 waterlogged samples of wheat remains (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Table 23) revealed a minute proportion (N = 49,005) of high-quality alignments with the domesticated tetraploid BA reference genome sequence of the cultivar Svevo, with signatures typical of age-dependent DNA damage28,29 (Supplementary Fig. 20). An almost complete absence of hits matching the D genome in analyses of alignments with the hexaploid wheat reference genome sequence of the cultivar Chinese Spring confirmed that the waterlogged remains corresponded to tetraploid wheat types (Supplementary Fig. 21). A principal component analysis (PCA) of the derived SNPs against the current tetraploid panel placed the ancient wheat samples from Chalain intermediate to GA (T. timopheevii and T. araraticum) and BA (DW, DEW and WEW) genome-containing taxa (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 22). Admixture analyses confirmed the presence of 25.7 ± 5.2% (unsupervised; Supplementary Fig. 23) and 58.6 ± 6.4% (supervised; Supplementary Fig. 24) ancestry characteristics of the GA-type wheats. Together, these results suggest that the investigated NGW sample was a GA wheat type, most probably a domesticated T. timopheevii, because wild T. araraticum is absent from all archaeological sites in the Fertile Crescent covering the time of the emergence of wheat domestication, or alternatively a member of the BA T. dicoccon group, or a hybrid between the two. Furthermore, an ancient Egyptian sample reported by Scott et al.30, included in our analysis, clearly clustered with DW_pop7 wheat genotypes (Horn of Africa and T. carthlicum), supporting the role of hybrids or gene flow in the emergence of cultivated wheats. Taken together, these findings lead us to revise the scenario for the evolution of modern wheats from their founder (A, B and D) ancestors (Fig. 7a).

a, An illustration of the evolutionary history of wheat and barley from A, B and D progenitors (top) and modern wild (dashed lines) and domesticated (plain lines) subspecies (that is, diploid wheats, DEW, DW, BW, tetraploid AG-type wheat (AGW) and tetraploid wild emmer wheat (WEW)), with associated spike illustrations (bottom). Modern wheat species (bottom) are reported with complete and simplified taxon names, as suggested by Sharma et al.6. b–d, A translational breeding approach comparing convergent signals of domestication and selection in wheat and barley obtained by the complementary CD-orthoSNP and orthoSweep approaches, for variants with a functional impact at the protein (HI variant HIV approach) and trait (comparative GWAS approach) levels (b), with examples of candidate genes with selective genomic footprints (CD-orthoSNP or orthoSweep) associated with a functional impact at the protein (HIV) or trait (GWAS) level (c), and the DCAF gene harbouring a convergent selection signal (in both CD-orthoSNP and orthoSweep analyses) associated with a functional impact on protein efficacy or function for which variants have been associated with grain weight in bread wheat (d).

By integrating orthoSweeps (948), CD-orthoSNPs (451), HI-variants (833) and GWAS(685) results (Fig. 1b), we were able to identify a non-redundant list of 1,371 genes showing signals of domestication and selection convergence with functional impacts at the protein and trait levels (Fig. 7b,c and Supplementary Table 24), highlighting key genes for breeding, including: (1) an RNA-binding region gene, RNP-1, with CD-orthoSNPs common to tetraploid wheat and barley, and associated with grain weight, heading date and plant height in barley; (2) a disease resistance gene (NBS-LRR class family) with CD-orthoSNPs common to tetraploid wheat and barley, and associated with HI variants; and (3) a WD40 repeat-like protein gene with a selective sweep signal associated with both HI variants and GWAS peaks (GW and HD) in bread wheat (Fig. 7c). The candidate genes identified may illustrate adaptation to changes in habitat and the associated constraints of domestication and selection during migration out of the centres of origin. Among these 1,371 genes, 15% (202) have already been functionally validated in barley and/or wheat (Online Datasets) and may be targets for cross-crop application in breeding, where the genetic variant (delivered in the current study) is conserved but the gene has been neither validated nor exploited in both species. Interestingly, we identified one gene, DDB1-CUL4 ASSOCIATED FACTOR (DCAF), harbouring a convergent selection signal (both CD-orthoSNP and orthoSweep) with a functional impact on protein efficacy or function (missense variant), variants of which are associated with grain weight in bread wheat. The DCAF gene is required for plant embryogenesis and is involved in several developmental processes, including leaf, shoot and flower development31 (Fig. 7d). The protein it encodes is also known to be abundant and conserved in mammals (mice and humans), where it plays important roles in various cell processes, including spermatogenesis32.

Discussion

Although several reports highlight convergent selection at the gene or locus level between species33,34,35, we are aware of only one study, on maize and rice19, that compares selection fingerprints at the genome-wide scale and nucleotide level between species, focusing on variants with signs of concomitant selection. Our current work, based on the analysis of selection and adaptation signals, reveals both complete and partial convergence. This opens the door to leveraging gene–allele information identified in one species to guide selection in another species where the trait holds potential breeding value—enabling inter-crop translational research for breeding. We provide clear evidence of parallel selection of variants at both the genome-wide and nucleotide levels, using complementary gene-based and block-based approaches to detect conserved selective sweeps and selected SNPs between wheat and barley. Despite their close evolutionary relationship, their genetic diversity is extremely unlikely to be shared by descent. This is due to polyploidization events in the recent evolutionary history of wheat, which represent severe genetic bottlenecks that permitted virtually no ancestral variation to be retained.

We applied a unique approach to the assessment of convergent selection in plants, based on systematic genome-wide scanning of intraspecific genetic diversity compared across several species, and demonstrated on a statistical basis that selection signatures are shared above random expectations for barley and wheat crops. We detected signs of convergent domestication and selection footprints for crop adaptation (resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses) and productivity (grain weight or yield, inflorescence development, spikelet architecture and tillering), and we detected clear allele differentiation between northern and southern distributions, particularly between the Horn of Africa and Mediterranean populations, for genes involved in stress and defence responses, as well as seed traits. Observed signatures of convergent selection could result from the parallel adaptation of barley and Triticum species to local environments, similar farming practices and common crop end uses. By studying changes in allele frequencies with the spread of these cereal crops into new environments, we were able to identify candidate genes putatively facilitating adaptation to heterogeneous pedoclimatic constraints. Previous studies have demonstrated the concomitant selection of the same genetic loci or genes in different crops19, but our new approach, in complement, delivers genetic (precise allele) drivers of local adaptation as potential prime targets for breeding.

An illustrative case is the convergent signals of selection we detected for barley and wheat at the FUWA gene, where in further examination we developed and phenotyped mutant plants at TdFUWA-A and TdFUWA-B loci in durum wheat. In rice, the FUWA protein is an RNA-binding factor regulating cell cycle progression that influences inflorescence architecture and grain-related traits, probably acting through brassinosteroid signals16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Phenotypic analysis of our mutant FUWA durum wheat plants showed effects on plant height, flowering time, leaf area and growth rates. This indicates a conserved function for FUWA between wheat and rice in controlling cell number and cell expansion during plant growth, but with effects in durum wheat that extend to flowering time and growth rate that were not reported for rice16. In another case, we showed the potential of convergent signals for identifying breeding-relevant genes and favourable alleles through exploring the role of DRO1 in tetraploid wheat in determining root architecture and supporting drought avoidance17,18. Phenotypic characterization of FUWA and DRO1 in tetraploid wheats illustrates the relevance of genes showing signals of convergent selection for consideration in breeding, regarding plant development and inflorescence architecture in the particular case of FUWA and root system architecture and drought avoidance in the particular case of DRO1.

Polyploidization, providing additional genetic material and evolutionary mechanisms, raises questions about the functional redundancy or specialization of duplicated genes37. It has been suggested that it is a key process in plant evolution, fuelling the acquisition of new gene functions critical in crop domestication38,39. In the current study, the genomic signatures identified in wheat indicate that, in the vast majority of cases, only one homoeologue within a homoeologous group is preferentially targeted by selection. This suggests an early, selection-driven functional and evolutionary dominance of a single homoeologous copy10. Our results conflict with previous reports that homologues or paralogues derived from polyploidization or whole-genome duplication were triggered by domestication and improvement40.

As well as improving our understanding of the domestication, selection and adaptation history of wheat and barley, our results illustrate how non-convergent (species-specific) signals of selection could be exploited in supporting translational breeding between crops. For individual species, we identified selection signals that were not shared across all species studied, opening the possibility of exploiting allelic states fixed in populations from specific geographic regions. These alleles probably represent genetic variants adapted to local pedoclimatic conditions and could be valuable for breeding programmes in species where such variants are not yet present in the elite gene pool. In particular, we identified T. timopheevii (GA-type) wheat as a source of unique genetic variants relative to domesticated durum (BA-type) wheats, with evidence of recurrent introgression and the identification of extinct cultivated new glume wheat, reported here as genetically closely related to (a possible hybrid of) GA-type wheat and T. dicoccon41,42,43. The cultivated NGW being possibly a domesticated T. timopheevii25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44 has far-reaching implications for our understanding of the complexity of the domestication process in wheat and confirms the role of multiple species in the evolution of domesticated forms, adding nuance to the ‘founder crops’ theory3 and reinforcing the interest in the AG-related genetic pool for modern wheat breeding45. The comparison of genomic data from ancient and modern crop forms offers new insights into the spatial and temporal origins of parallel domestication events in wheat across all ploidy levels6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46.

By applying the knowledge provided by this study to revise breeding and conservation strategies, new avenues for addressing future food security are opened. From our understanding of the parallel, or repeated, evolution of wheat and barley provided through comparative genomics, we can now associate genetic variants of favourable phenotypes and traits with orthologues in alternate species. Our clearer understanding of the sometimes parallel and sometimes unique adaptation of crop species more broadly should enhance modern plant breeding approaches widely.

Methods

The materials and methods are summarized below. A more detailed description is provided in the Supplementary Information. Comparative genomics and ATK Triticeae genomes were compared (BlastP between annotated proteomes) to identify orthologous genes with OrthoFinder47. We defined families of conserved genes, referred to as OGs, to infer the ancestral Triticeae karytope (ATK). We identified 32,833 OGs, including 11,925 ‘perfectly conserved’ genes and 7,328 ‘partially conserved’ genes. SNP calling In total, 679 barley (Hordeum vulgare and H. spontaneum) and 672 wheat (252 tetraploid and 420 hexaploid) genotypes representative of the broad diversity of cultivars, landrace and wild genotypes sampled across their ecogeographic ranges were sequenced for exome diversity analysis, as described by Pont et al.13, with mapping onto the corresponding reference genome (that is, cv. Chinese Spring for hexaploid wheat, cv. Svevo for tetraploid wheat and cv. Morex for barley) with BWA-MEM48. Further preprocessing of the resulting BAM files was performed with GATK v.3.4.0 in accordance with the GATK Best Practices pipeline49, with the GATK HaplotypeCaller and join GenotypeCaller tools50. The resulting bam files were then used for the joint calling of variants by chromosome with samtools mpileup (version 1.3), using parameters --min-MQ 20, --excl-flags UNMAP,SECONDARY,QCFAIL,DUP (samtools) and bcftools call (version 1.3) with parameters -vcO z -f GQ. In the population structure datasets, sites with a high proportion of missing calls (>0.333) and sites with outlier sum depth values were removed, leaving 536,669, 799,883 and 236,760 SNPs for cultivated barley, tetraploid and hexaploid wheats, respectively (Online Datasets). Regarding the datasets for the analysis of selection signatures, sites with >10% heterozygous calls were removed, and missing genotype calls were imputed with Beagle5.351. This imputed dataset consisted of 1,850,997, 1,537,720 and 485,900 SNPs for barley, tetraploid and hexaploid wheats, respectively (Online Datasets). Population structure Genetic populations were defined separately within each of the four taxon groups of HV, DW, DEW and BW on the basis of PCA, sparse non-negative matrix factorization (sNMF) ancestry coefficients52, maximum-likelihood tree topology and passport data. PCA was performed with smartpca from the EIGENSOFT package53, with the least-squares PCA projection, without outlier removal. sNMF was run for K2–15 with five iterations, using various values of the regularization parameter (10–1,000). The maximum-likelihood phylogeny was inferred with iqtree54, using Modelfinder55 to identify the optimal substitution model (TVM + F + ASC + R4 for wheat datasets and TVM + F + ASC + R3 for barley). Geographic coordinates were used to locate samples with the map_data function from the R package ggplot256. When known for samples, precise Global Positioning System positions were used; in the absence of such data, coordinates of the capital of the country of sampling were applied for location purposes. Latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates averaged across all the individuals of a given population were used to locate populations on maps. CD-orthoSNP identification We used a set of 19,253 conserved gene families (or OG) with a total of 3,923,023 original non-imputed SNPs identified in the exome data for the Triticeae species investigated for a multi-sequence alignment57 to identify orthoSNPs, that is, polymorphisms at orthologous nucleotide positions within the corresponding genes in barley, tetraploid and hexaploid wheats. We considered ‘differentiated’ orthoSNPs (that is, orthoSNPs with contrasting allelic frequencies in at least two populations of a particular crop) to be indicative of selection, and we identified ‘concomitantly differentiated’ orthoSNPs (CD-orthoSNPs) as those showing differentiated allele patterns (≦0.1 and ≧0.9 frequency thresholds) in two or more crops simultaneously. Phylogeny inference Phylogenomic analysis was performed with repeated random haplotype sampling trees (RRHS)58 by generating conventional consensus topologies and densitree visualizations to infer taxonomic clades. We analysed the evolutionary distances between the tips of 1,000 trees with the minimum spanning tree algorithm in Python. The minimum spanning tree graphs were subsequently combined into a weighted phylogenetic consensus network, the nodes of which were clustered into clades with the Girvan–Newman edge-betweenness algorithm in Cytoscape59. The clustered network topology was plotted taking into account edge-betweenness in Cytoscape, and taxonomic clades were inferred by intersecting community clusters with taxon information annotated with the AutoAnnotate plugin. The phylogenetic tree for wheat accessions was generated from orthoSNPs datasets for tetraploids and hexaploids converted into the pseudo vcf format. The resulting vcf files were then used as input to create a matrix for phylogenetic analysis (in PHYLIP format), as described by Ortiz60. The final trees (in Newick format) were drawn with iqtree261 for the A and B subgenomes separately, as well as for the combined dataset including both subgenomes, covering both tetraploid and hexaploid wheats. Visualization was performed and plots were generated with the ggtree R package62. FUWA and DRO1 gene characterization Haplotype characterization was based on SNPs located in FUWA and DRO1 gene intervals extracted from vcf files using vcftools63, with haplotype network analysis performed with the geneHapR R package64, consensus haplotype sequences retrieved from the vcf files using bcftools consensus and cross-species multiple haplotype alignment (after manual masking of species-specific SNPs), and NJ tree constructed using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) 11 software65. From TdFUWA-A (RITD6Av1G100490) and TdFUWA-B (TRITD6Bv1G115800), a target region of about 1 kb was identified using the Cas-Designer tool66 to perform durum wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. durum, cultivar Svevo) transformation from immature embryos by particle bombardment followed by regeneration and selection of transformed calluses as in the work of He et al.67. For comparison with DRO1 haplotype states, phenotypic characterization of root growth angle of seedlings grown for 5 days at 22 °C under a 16-h light photoperiod in semi-hydroponic conditions (methods as described by Maccaferri et al.68 and Rufo et al.69) was undertaken for 100 domesticated emmer and durum-turgidum accessions that were selected to represent diverse subpopulations, with the exclusion of AG and WEW. HI variant analysis HI SNPs were identified with SnpEff70, using the default parameters for all ‘non-reference’ alleles (that is, those differing from the alleles of the reference genomes used for tetraploid and hexaploid wheats, and barley). Statistics on variant numbers, types and allele frequencies in populations (VAF = number of variant alleles/total number of alleles) were computed in R. Enrichment analyses for annotated Gene Ontology (GO)71 biological processes (GO-BP, GO term size >10) were performed with gprofiler272 for the genes carrying HI variants, with a threshold of 0.05 and Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing. Functional investigations of the impact of variants on plant phenotypes at the cross-species level were performed by querying the RARGE II database73 to obtain information on Arabidopsis genes for which mutations result in significant changes in phenotype. Comparative GWAS analysis Barley and hexaploid wheat SNPs were associated with phenotypic data collected as previously described12,13. GWAS were run separately for each trait in each environment, using the imputed SNP datasets filtered for MAF 0.05 (about ~900,000 and ~400,000 SNPs for barley and wheat, respectively), with the statgenGWAS R package74. For the identification of loci reproducibly associated with the traits under study in different environments, we used the summary statistics from single GWAS as input for a meta-analysis with METAL75, implementing a sample size-weighted fixed-effects model. Two different thresholds were considered for declaring SNP markers significant in the meta-analysis: within the top 0.5% of the whole-genome P-value distribution and a P value <0.0001 after the application of a genomic control correction method. Detection of orthoSweeps Three different signatures of selection based on particular patterns of LD (omega76), interpopulation differentiation (FST) and diversity (θW*MAF; that is, the product of Watterson’s theta and MAF) were assessed for each population and every individual position of the imputed vcf datasets. The three metrics were first summarized in contiguous genomic blocks for the identification of sweeps in each population. Sweeps were defined as contiguous regions containing two or more adjacent vcf positions passing the metric threshold (defined as percentiles of the genome-wide distribution for each metric). The comparative nature of our analyses (that is, the search for convergent selection signals across multiple species) made it possible to quantify signal enrichment, that is, the ratio of observed sweep-sharing across species and the sweep-sharing expected by chance. For this purpose, we considered each gene from the 11,925 ‘perfect’ OGs as an independent selection unit associated with specific values of the three statistics (omega, FST and θW*MAF; each standardized as a z score). Random sweep-sharing could then be calculated as the expected number of orthogenes (ogexpected) with selection statistics above a particular percentile simultaneously in multiple crops or subgenomes. Sweep-sharing levels exceeding random (neutral) expectations were then considered to be indicative of convergent selection forces. Signal enrichment (that is, ogobserved/ogexpected) >20× implies that above this threshold, less than 1 in 20 OGs are detected in multiple crops or subgenomes by chance. Accordingly, we calculated signal enrichment for an array of percentiles (from 0.6 to 0.99 with 0.01 increments, and for 0.999) for each of the three statistics and their linear combination zc, and we considered orthogenes yielding enrichment signals (that is, ogobserved/ogexpected) >20× to be directly or indirectly (by linkage) associated with convergent selection. Investigation of ancient wheat For ancient DNA extraction, each sample was rinsed in water and air-dried under ultraviolet irradiation in a clean room. The sample was ground to a powder without liquid nitrogen (Retsch MM400) and placed in a 1.5-ml tube for DNA extraction. We then added 1 ml extraction buffer containing 1% CTAB together with 20 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1.5 M NaCl and 3% crosslinked polyvinylpyrrolidone. The sample was suspended by vortexing, incubated at 55 °C for 1 h and then incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 24 h. For controls, exactly the same protocol was used but without the powdered sample. Using the silica column-based method described by Dabney et al.77, we centrifuged the extracts at maximum speed (16,100g) for 5 min. The supernatant was transferred to a 50-ml tube with a binding apparatus reservoir containing 13 ml of binding buffer (including guanidine hydrochloride, isopropanol, sodium acetate and Tween 20). After centrifugation at 1,500g for 7 min, the extension reservoir of the MinElute column was removed and placed in a clean 2-ml collection tube. The MinElute column was spun dry at 3,300g for 1 min in a benchtop centrifuge. Two washing steps were performed by adding 750 μl PE buffer (Qiagen) to the MinElute column, spinning at 3,300g for 1 min and discarding the flowthrough. The column was spun dry at maximum speed (16,100g) for 1 min and then transferred to a fresh 1.5-ml collection tube. For elution, 12.5 μl TET buffer (1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris–HCl and 0.05% Tween 20) was applied to the silica membrane with a pipette and collected by centrifugation at maximum speed for 30 s, after incubation with the membrane for 2–5 min. This step was repeated to yield a total of 25 μl of DNA extract. The library was constructed with a protocol for sequencing on the Illumina sequencing platform optimized for ancient and degraded DNA78, with splinted ligation for simultaneous ligation of the Illumina P5 and P7 adapters. We mapped 131,580 wheat reads onto the National Center for Biotechnology Information nucleotide database with BLASTn2.11.0+ (release April 2022), using the default parameters, and analysed them in MEGAN6.22.279 using the naive last common ancestor algorithm for binning. PCA analysis was performed with the smartPCA tool from the EIGENSOFT package (version 5.0; https://github.com/chrchang/eigensoft/blob/master/POPGEN/README), with outlier removal turned off. The genotype matrix was converted into Fasta format to run IQtree 2.2.0.380 and generate phylogenetic trees from the different samples. The results were visualized in Dendroscope79. The demultiplexed fastq read pairs were processed with PALEOMIX81 bam_pipeline v1.2.13.2. Sequencing adaptors were trimmed and paired-end reads were collapsed with AdapterRemoval282 v2.3.1, using the default parameters. All the resulting reads—that is, those collapsed (and possibly truncated for lower quality ends) and those remaining paired—were aligned against a tetraploid free-threshing wheat (cultivar Svevo) reference genome, with bwa83 v.0.7.17-r1194-dirty, disabling seeding and using the mapping options -n: 0.1 -o: 2. PCR duplicates were removed with Picard MarkDuplicates (http://picard.sourceforge.net), and DNA fragmentation and nucleotide misincorporation patterns were visualized with mapDamage284 v.2.0.8 using the default parameters. The BAM alignment file was further filtered for alignments of at least 32 bp and was processed with PMDtools85 v0.60 and the trim_bam.py python script from Librado et al.86 to reduce the impact of post-mortem DNA damage on downstream analyses. Pseudohaploid genotypes were called with ANGSD87 v.0.930 (htslib: 1.9), skipping positions and/or reads with base and/or mapping Phred-quality scores strictly lower than 30 (--doHaploCall 1 -doCounts 1 -minMapQ 30 -minQ 30 -remove_bads 1 -uniqueOnly 1) and restricting calls to the 1,537,720 SNP positions covered in the vfc file of the modern diversity. The genetic variation present in our SNP panel was investigated by PCA with smartpca53 and ADMIXTURE88 v.1.3.0. In addition to the palaeogenomics investigation described above, we performed an automated morphometry analysis (based on the length of abscission scars and U-shaped curves for measurements of ten parameters) of spikelet remains, comparing the results with those for experimentally charred modern spikelets and carpological references.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Online datasets are made available at https://entrepot.recherche.data.gouv.fr/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi%3A10.57745%2FMX18MU&version=DRAFT delivering 1) the list of orthogroups between Triticeae genomes, 2) the passport information of the barley and wheat accessions, 3) the Vcf files of nonimputed and imputed SNPs for barley, tetraploid and hexaploid wheats, 4) the matrices of orthoSNPs for barley, tetraploid and hexaploid wheats and 5) the list of candidate genes and functional validation information. The raw exome-sequencing data have been made publicly available for barley (PRJEB8044), tetraploid (PRJNA1152310 and PRJNA1156184) and hexaploid (PRJNA524104) wheats.

Change history

24 November 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-02182-8

References

Dyson, R. H. The archaeological evidence of cultivated wheat and barley in near eastern prehistory. Mem. Soc. Am. Archaeol. 9, 7–11 (1953).

Kilian, B., Martin, W. & Salamini, F. in Evolution in Action: Case Studies in Adaptive Radiation, Speciation and the Origin of Biodiversity (ed Glaubrecht, M.) 137–166 (Springer, 2010); https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-12425-9_8

Zohary, D., Hopf, M. & Weiss, E. Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin 4th edn (Oxford Univ. Press, 2012); https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199549061.001.0001

Middleton, C. P. et al. Sequencing of chloroplast genomes from wheat, barley, rye and their relatives provides a detailed insight into the evolution of the Triticeae tribe. PLoS ONE 9, e85761 (2014).

Bernhardt, N. et al. Dated tribe-wide whole chloroplast genome phylogeny indicates recurrent hybridizations within Triticeae. BMC Evol. Biol. 17, 141 (2017).

Sharma, S. et al. Introducing beneficial alleles from plant genetic resources into the wheat germplasm. Biology 10, 982 (2021).

Pourkheirandish, M. & Komatsuda, T. Grain disarticulation in wild wheat and barley. Plant Cell Physiol. 63, 1584–1591 (2022).

Woodhouse, M. R. & Hufford, M. B. Parallelism and convergence in post-domestication adaptation in cereal grasses. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180245 (2019).

Civáň, P. When bitter is better. Nat. Plants 5, 1205–1206 (2019).

Bellec, A. et al. Tracing 100 million years of grass genome evolutionary plasticity. Plant J. 114, 1243–1266 (2023).

Murat, F., Armero, A., Pont, C., Klopp, C. & Salse, J. Reconstructing the genome of the most recent common ancestor of flowering plants. Nat. Genet. 49, 490–496 (2017).

Bustos-Korts, D. et al. Exome sequences and multi-environment field trials elucidate the genetic basis of adaptation in barley. Plant J. 99, 1172–1191 (2019).

Pont, C. et al. Tracing the ancestry of modern bread wheats. Nat. Genet. 51, 905–911 (2019).

Matsuoka, Y. Evolution of polyploid triticum wheats under cultivation: the role of domestication, natural hybridization and allopolyploid speciation in their diversification. Plant Cell Physiol. 52, 750–764 (2011).

Tian, J. et al. Overexpression of OsPAP10a, a root-associated acid phosphatase, increased extracellular organic phosphorus utilization in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 54, 631–639 (2012).

Chen, J. et al. An evolutionarily conserved gene, FUWA, plays a role in determining panicle architecture, grain shape and grain weight in rice. Plant J. 83, 427–438 (2015).

Uga, Y., Okuno, K. & Yano, M. Dro1, a major QTL involved in deep rooting of rice under upland field conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 2485–2494 (2011).

Uga, Y. et al. Control of root system architecture by DEEPER ROOTING 1 increases rice yield under drought conditions. Nat. Genet. 45, 1097–1102 (2013).

Chen, W. et al. Convergent selection of a WD40 protein that enhances grain yield in maize and rice. Science 375, eabg7985 (2022).

Han, X., Zhang, M., Yang, M. & Hu, Y. Arabidopsis JAZ proteins interact with and suppress RHD6 transcription factor to regulate jasmonate-stimulated root hair development. Plant Cell 32, 1049–1062 (2020).

Jia, H., Aadland, K., Kolaczkowski, O. & Kolaczkowski, B. Direct molecular evidence for an ancient, conserved developmental toolkit controlling posttranscriptional gene regulation in land plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 4765–4777 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. The ubiquitin-binding protein OsDSK2a mediates seedling growth and salt responses by regulating gibberellin metabolism in rice. Plant Cell 32, 414–428 (2020).

Nguyen, L. V., Seok, H. Y., Woo, D. H., Lee, S. Y. & Moon, Y. H. Overexpression of the DEAD-box RNA helicase gene AtRH17 confers tolerance to salt stress in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 3777 (2018).

Tsuji, H., Taoka, K. & Shimamoto, K. Regulation of flowering in rice: two florigen genes, a complex gene network, and natural variation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14, 45–52 (2011).

Badaeva, E. D. et al. Genetic diversity, distribution and domestication history of the neglected GGAtAt genepool of wheat. Theor. Appl Genet. 135, 755–776 (2022).

Przewieslik-Allen, A. M. et al. The role of gene flow and chromosomal instability in shaping the bread wheat genome. Nat. Plants 7, 172–183 (2021).

Kenéz, Á, Pető, Á & Gyulai, F. Evidence of ‘new glume wheat’ from the Late Neolithic (Copper Age) of south-eastern Hungary (4th millennium cal. B.C.). Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 23, 551–566 (2014).

Briggs, A. W. et al. Patterns of damage in genomic DNA sequences from a Neandertal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 14616–14621 (2007).

Stiller, M. et al. Patterns of nucleotide misincorporations during enzymatic amplification and direct large-scale sequencing of ancient DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 13578–13584 (2006).

Scott, M. F. et al. A 3,000-year-old Egyptian emmer wheat genome reveals dispersal and domestication history. Nat. Plants 5, 1120–1128 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Arabidopsis DDB1-CUL4 ASSOCIATED FACTOR1 forms a nuclear E3 ubiquitin ligase with DDB1 and CUL4 that is involved in multiple plant developmental processes. Plant Cell 20, 1437–1455 (2008).

Mistry, B. V. et al. Expression profiling of WD40 family genes including DDB1- and CUL4-associated factor (DCAF) genes in mice and human suggests important regulatory roles in testicular development and spermatogenesis. BMC Genomics 21, 602 (2020).

Lenser, T. & Theißen, G. Molecular mechanisms involved in convergent crop domestication. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 704–714 (2013).

Chamberlain-Irwin, H. N. & Hufford, M. B. Convergent domestication: finding the genes that make crops. Curr. Biol. 32, R585–R588 (2022).

Xu, S., Wang, J., Guo, Z., He, Z. & Shi, S. Genomic convergence in the adaptation to extreme environments. Plant Commun. 1, 100117 (2020).

Xu, Z. et al. Large Grain 2, an NHL domain-containing protein, interacts with FUWA and regulates plant architecture and grain size through the brassinosteroid signaling pathway in rice. Rice 18, 37–41 (2025).

Van de Peer, Y., Ashman, T. L., Soltis, P. S. & Soltis, D. E. Polyploidy: an evolutionary and ecological force in stressful times. Plant Cell 33, 11–26 (2021).

Fang, Z. & Morrell, P. Domestication: polyploidy boosts domestication. Nat. Plants 2, 16116 (2016).

Salman-Minkov, A., Sabath, N. & Mayrose, I. Whole-genome duplication as a key factor in crop domestication. Nat. Plants 2, 16115 (2016).

Li, T. et al. Intra-varietal diversity and its contribution to wheat evolution, domestication, and improvement in wheat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 10217 (2023).

Czajkowska, B. I. et al. Ancient DNA typing indicates that the ‘new’ glume wheat of early Eurasian agriculture is a cultivated member of the Triticum timopheevii group. J. Archaeol. Sci. 123, 105258 (2020).

Jones, G., Valamoti, S. & Charles, M. Early crop diversity: a ‘new’ glume wheat from northern Greece. Veget. Hist. Archaebot. 9, 133–146 (2000).

Ulaş, B. & Fiorentino, G. Recent attestations of ‘new’ glume wheat in Turkey: a reassessment of its role in the reconstruction of Neolithic agriculture. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 30, 685–701 (2021).

Filipović, D. et al. Triticum timopheevii s.l. (‘new glume wheat’) finds in regions of southern and eastern Europe across space and time. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 33, 195–208 (2023).

Zeibig, F., Kilian, B., Özkan, H., Pantha, S. & Frei, M. Phenotyping and identification of target traits for de novo domestication of wheat wild relatives. Food Energy Secur. 13, e497 (2024).

Di Donato, A., Filippone, E., Ercolano, M. R. & Frusciante, L. Genome sequencing of ancient plant remains: findings, uses and potential applications for the study and improvement of modern crops. Front Plant Sci. 9, 441 (2018).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20, 238 (2019).

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997 (2013).

Van Der Auwera, G. A. et al. From FastQ data to high-confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit Best Practices Pipeline. CP Bioinf. 43, 11.10.1–11.1033 (2013).

Poplin, R. et al. Scaling accurate genetic variant discovery to tens of thousands of samples. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/201178 (2018).

Browning, B. L., Tian, X., Zhou, Y. & Browning, S. R. Fast two-stage phasing of large-scale sequence data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 1880–1890 (2021).

Frichot, E., Mathieu, F., Trouillon, T., Bouchard, G. & François, O. Fast and efficient estimation of individual ancestry coefficients. Genetics 196, 973–983 (2014).

Patterson, N., Price, A. L. & Reich, D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2, e190 (2006).

Nguyen, L.-T., Schmidt, H. A., Von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015).

Kalyaanamoorthy, S., Minh, B. Q., Wong, T. K. F., Von Haeseler, A. & Jermiin, L. S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14, 587–589 (2017).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer, 2016).

Bawono, P. et al. in Bioinformatics Vol. 1525 (ed Keith, J. M.) 167–189 (Springer, 2017).

Lischer, H. E. L., Excoffier, L. & Heckel, G. Ignoring heterozygous sites biases phylogenomic estimates of divergence times: implications for the evolutionary history of Microtus voles. Mol. Biol. Evolution 31, 817–831 (2014).