Abstract

Widespread climate-driven increases in background tree mortality rates have the potential to reduce the carbon storage of terrestrial ecosystems, challenging their effectiveness as natural buffers against atmospheric CO2 enrichment with major consequences for the global carbon budget. However, the global extent of trends in tree mortality and their drivers remains poorly quantified. The Australian continent experiences one of the most variable climates on Earth and is host to a diverse range of forest biomes that have evolved high resistance to disturbance, providing a valuable test case for the pervasiveness of tree mortality trends. Here we compile an 83-year tree dynamics database (1941–2023) from >2,700 forest plots across Australia covering tropical savanna and rainforest and warm and cool temperate forests, to explore spatiotemporal patterns of tree mortality and the associated drivers. Over the past eight decades, we found a consistent trend of increasing tree mortality across the four forest biomes. This temporal trend persisted after accounting for stand structure and was exacerbated in forests with low moisture index or a high competition index. Species with traits associated with high growth rate—low wood density, high specific leaf area and short maximum height—exhibited higher average mortality, but the rate of mortality increase was comparable across different functional groups. Increasing mortality was not associated with increasing growth, given that stand basal area increments either declined or remained unchanged over time, but it was associated with increasing temperature over time. Our findings suggest that ongoing climate change has driven pervasive shifts in forest dynamics beyond natural recovery in a range of forest biomes with high resilience to disturbance, threatening the enduring capacity of forests to sequester carbon under current and future climate scenarios.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The tree-by-tree observations are publicly available via Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28407893 (ref. 98). However, some datasets have been anonymized (for example, geographic locations removed) or excluded, as required by dataset custodians (Supplementary Table 1). The records of tropical cyclone events occurring in QPRP-CSIRO plots can be accessed via https://data.csiro.au/collection/csiro:6638v3. The Bushfire Boundaries dataset is available from the Digital Atlas of Australia (Historical Bushfire Boundaries|Historical Bushfire Boundaries|Digital Atlas of Australia). For climate, the SPEI dataset is available at https://spei.csic.es/spei_database_2_10. The moisture index dataset is available at CGIAR CSI Global Aridity and PET Database. TerraClimate dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.191. The AusTraits database is available at https://austraits.org/.

Code availability

The codes used for this study are available via Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28407893 (ref. 98).

References

Adams, H. D. et al. Climate-induced tree mortality: Earth system consequences. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 91, 153–154 (2010).

McDowell, N. G. et al. Pervasive shifts in forest dynamics in a changing world. Science 368, eaaz9463 (2020).

Ruiz-Benito, P. et al. Climate-and successional-related changes in functional composition of European forests are strongly driven by tree mortality. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 4162–4176 (2017).

Needham, J. F., Chambers, J., Fisher, R., Knox, R. & Koven, C. D. Forest responses to simulated elevated CO2 under alternate hypotheses of size- and age-dependent mortality. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 5734–5753 (2020).

Hiltner, U., Huth, A. & Fischer, R. Importance of the forest state in estimating biomass losses from tropical forests: combining dynamic forest models and remote sensing. Biogeosciences 19, 1891–1911 (2022).

Brienen, R. J. W. et al. Long-term decline of the Amazon carbon sink. Nature 519, 344–348 (2015).

Bauman, D. et al. Tropical tree mortality has increased with rising atmospheric water stress. Nature 608, 528–533 (2022).

van Mantgem, P. J. et al. Widespread increase of tree mortality rates in the western United States. Science 323, 521–524 (2009).

McDowell, N. G. et al. Multi-scale predictions of massive conifer mortality due to chronic temperature rise. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 295–300 (2015).

Senf, C. et al. Canopy mortality has doubled in Europe’s temperate forests over the last three decades. Nat. Commun. 9, 4978 (2018).

Peng, C. H. et al. A drought-induced pervasive increase in tree mortality across Canada’s boreal forests. Nat. Clim. Change 1, 467–471 (2011).

Hubau, W. et al. Asynchronous carbon sink saturation in African and Amazonian tropical forests. Nature 579, 80–87 (2020).

Hammond, W. M. et al. Global field observations of tree die-off reveal hotter-drought fingerprint for Earth’s forests. Nat. Commun. 13, 1761 (2022).

Hartmann, H. et al. Climate change risks to global forest health: emergence of unexpected events of elevated tree mortality worldwide. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 73, 673–702 (2022).

Yu, K. L. et al. Pervasive decreases in living vegetation carbon turnover time across forest climate zones. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 24662–24667 (2019).

Ma, Z. H. et al. Regional drought-induced reduction in the biomass carbon sink of Canada’s boreal forests. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 2423–2427 (2012).

Rammig, A. & Lapola, D. M. The declining tropical carbon sink. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 727–728 (2021).

Network, I. T. M. Towards a global understanding of tree mortality. N. Phytol. 245, 2377–2392 (2025).

Pugh, T. A. M. et al. Understanding the uncertainty in global forest carbon turnover. Biogeosciences 17, 3961–3989 (2020).

Wei, N. et al. Evolution of uncertainty in terrestrial carbon storage in Earth system models from CMIP5 to CMIP6. J. Clim. 35, 5483–5499 (2022).

Gallagher, R. V., Allen, S. & Wright, I. J. Safety margins and adaptive capacity of vegetation to climate change. Sci. Rep. 9, 8241 (2019).

King, A. D., Pitman, A. J., Henley, B. J., Ukkola, A. M. & Brown, J. R. The role of climate variability in Australian drought. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 177–179 (2020).

Peters, J. M. R. et al. Living on the edge: A continental-scale assessment of forest vulnerability to drought. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 3620–3641 (2021).

Larter, M. et al. Extreme aridity pushes trees to their physical limits. Plant Physiol. 168, 804–807 (2015).

Crombie, D., Tippett, J. & Hill, T. Dawn water potential and root depth of trees and understorey species in southwestern Australia. Aust. J. Bot. 36, 621–631 (1988).

Myers, B. A. et al. Seasonal variation in water relations of trees of differing leaf phenology in a Wet-dry tropical savanna near Darwin, Northern Australia. Aust. J. Bot. 45, 225–240 (1997).

Lawes, M. J. et al. Appraising widespread resprouting but variable levels of postfire seeding in Australian ecosystems: the effect of phylogeny, fire regime and productivity. Aust. J. Bot. 70, 114–130 (2022).

Yang, S., Ooi, M. K. J., Falster, D. S. & Cornwell, W. K. Continental-scale empirical evidence for relationships between fire response strategies and fire frequency. N. Phytol. 246, 528–542 (2025).

Forzieri, G., Dakos, V., McDowell, N. G., Ramdane, A. & Cescatti, A. Emerging signals of declining forest resilience under climate change. Nature 608, 534–539 (2022).

De Kauwe, M. G. et al. Identifying areas at risk of drought-induced tree mortality across South-Eastern Australia. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 5716–5733 (2020).

The Dead Tree Detective. Western Sydney University (accessed 5 December 2025); https://biocollect.ala.org.au/acsa/project/index/77285a13-e231-49e8-b212-660c66c74bac

Yan, Y. et al. Climate-induced tree-mortality pulses are obscured by broad-scale and long-term greening. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 912–923 (2024).

Esquivel-Muelbert, A. et al. Tree mode of death and mortality risk factors across Amazon forests. Nat. Commun. 11, 5515 (2020).

Luo, Y. & Chen, H. Y. H. Observations from old forests underestimate climate change effects on tree mortality. Nat. Commun. 4, 1655 (2013).

Luo, Y. & Chen, H. Y. H. Climate change-associated tree mortality increases without decreasing water availability. Ecol. Lett. 18, 1207–1215 (2015).

Trouvé, R., Baker, P. J., Ducey, M. J., Robinson, A. P. & Nitschke, C. R. Global warming reduces the carrying capacity of the tallest angiosperm species (Eucalyptus regnans). Nat. Commun. 16, 7440 (2025).

Thorpe, H. C. & Daniels, L. D. Long-term trends in tree mortality rates in the Alberta foothills are driven by stand development. Can. J. Res. 42, 1687–1696 (2012).

Doughty, C. E. et al. Tropical forests are approaching critical temperature thresholds. Nature 621, 105–111 (2023).

Ping, J. et al. Enhanced causal effect of ecosystem photosynthesis on respiration during heatwaves. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi6395 (2023).

Hicke, J. A. & Zeppel, M. J. B. Climate-driven tree mortality: insights from the pinon pine die-off in the United States. N. Phytol. 200, 301–303 (2013).

Grossiord, C. et al. Plant responses to rising vapor pressure deficit. N. Phytol. 226, 1550–1566 (2020).

Zhou, S., Zhang, Y., Williams, A. P. & Gentine, P. Projected increases in intensity, frequency, and terrestrial carbon costs of compound drought and aridity events. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau5740 (2019).

Will, R. E., Wilson, S. M., Zou, C. B. & Hennessey, T. C. Increased vapor pressure deficit due to higher temperature leads to greater transpiration and faster mortality during drought for tree seedlings common to the forest-grassland ecotone. N. Phytol. 200, 366–374 (2013).

McDowell, N. G. & Allen, C. D. Darcy’s law predicts widespread forest mortality under climate warming. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 669–672 (2015).

Carle, H. et al. Aboveground biomass in Australian tropical forests now a net carbon source. Nature 646, 611–618 (2025).

Zuleta, D. et al. Individual tree damage dominates mortality risk factors across six tropical forests. N. Phytol. 233, 705–721 (2021).

Murphy, H. T., Bradford, M. G., Dalongeville, A., Ford, A. J. & Metcalfe, D. J. No evidence for long-term increases in biomass and stem density in the tropical rain forests of Australia. J. Ecol. 101, 1589–1597 (2013).

Wright, S. J. et al. Functional traits and the growth-mortality trade-off in tropical trees. Ecology 91, 3664–3674 (2010).

Ruger, N. et al. Beyond the fast-slow continuum: demographic dimensions structuring a tropical tree community. Ecol. Lett. 21, 1075–1084 (2018).

Ruger, N. et al. Demographic trade-offs predict tropical forest dynamics. Science 368, 165–168 (2020).

Callahan, R. P. et al. Forest vulnerability to drought controlled by bedrock composition. Nat. Geosci. 15, 714–719 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. Hydraulic traits are coordinated with maximum plant height at the global scale. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav1332 (2019).

Givnish, T. J., Wong, S. C., Stuart-Williams, H., Holloway-Phillips, M. & Farquhar, G. D. Determinants of maximum tree height in Eucalyptus species along a rainfall gradient in Victoria, Australia. Ecology 95, 2991–3007 (2014).

Iida, Y. et al. Linking functional traits and demographic rates in a subtropical tree community: the importance of size dependency. J. Ecol. 102, 641–650 (2014).

Muller-Landau, H. C. et al. Testing metabolic ecology theory for allometric scaling of tree size, growth and mortality in tropical forests. Ecol. Lett. 9, 575–588 (2006).

Piponiot, C. et al. Distribution of biomass dynamics in relation to tree size in forests across the world. N. Phytol. 234, 1664–1677 (2022).

Gora, E. M. & Esquivel-Muelbert, A. Implications of size-dependent tree mortality for tropical forest carbon dynamics. Nat. Plants 7, 384–391 (2021).

Lu, R. L. et al. The U-shaped pattern of size-dependent mortality and its correlated factors in a subtropical monsoon evergreen forest. J. Ecol. 109, 2421–2433 (2021).

Hülsmann, L. et al. Latitudinal patterns in stabilizing density dependence of forest communities. Nature 627, 564–571 (2024).

Barrere, J. et al. Functional traits and climate drive interspecific differences in disturbance-induced tree mortality. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 2836–2851 (2023).

Coomes, D. A., Duncan, R. P., Allen, R. B. & Truscott, J. Disturbances prevent stem size-density distributions in natural forests from following scaling relationships. Ecol. Lett. 6, 980–989 (2003).

Coomes, D. A. & Allen, R. B. Mortality and tree-size distributions in natural mixed-age forests. J. Ecol. 95, 27–40 (2007).

Trouvé, R., Oborne, L. & Baker, P. J. The effect of species, size, and fire intensity on tree mortality within a catastrophic bushfire complex. Ecol. Appl. 31, e02383 (2021).

Barlow, J., Peres, C. A., Lagan, B. O. & Haugaasen, T. Large tree mortality and the decline of forest biomass following Amazonian wildfires. Ecol. Lett. 6, 6–8 (2003).

Bendall, E. R. et al. Demographic change and loss of big trees in resprouting eucalypt forests exposed to megadisturbance. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 33, e13842 (2024).

Murphy, B. P. et al. Using a demographic model to project the long-term effects of fire management on tree biomass in Australian savannas. Ecol. Monogr. 93, e1564 (2023).

Prior, L. D., Murphy, B. P. & Russell-Smith, J. Environmental and demographic correlates of tree recruitment and mortality in north Australian savannas. Ecol. Manag. 257, 66–74 (2009).

Bialic-Murphy, L. et al. The pace of life for forest trees. Science 386, 92–98 (2024).

Johnson, D. J. et al. Climate sensitive size-dependent survival in tropical trees. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1436–1442 (2018).

Oliver, C. D. & Larson, B. A. 'Forest Stand Dynamics, Update Edition'. in Yale School of the Environment Other Publications 1 (1996); https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/fes_pubs/1

Wang, J., Taylor, A. R. & D’Orangeville, L. Warming-induced tree growth may help offset increasing disturbance across the Canadian boreal forest. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2212780120 (2023).

Trouvé, R., Bontemps, J.-D., Collet, C., Seynave, I. & Lebourgeois, F. Growth partitioning in forest stands is affected by stand density and summer drought in sessile oak and Douglas-fir. Ecol. Manag. 334, 358–368 (2014).

Chen, L. et al. Global increase in the occurrence and impact of multiyear droughts. Science 387, 278–284 (2025).

Yuan, X. et al. A global transition to flash droughts under climate change. Science 380, 187–191 (2023).

Yu, K. L. et al. Field-based tree mortality constraint reduces estimates of model-projected forest carbon sinks. Nat. Commun. 13, 2094 (2022).

Bugmann, H. et al. Tree mortality submodels drive simulated long-term forest dynamics: assessing 15 models from the stand to global scale. Ecosphere 10, e02616 (2019).

Moorcroft, P. R., Hurtt, G. C. & Pacala, S. W. A method for scaling vegetation dynamics: the ecosystem demography model (ED). Ecol. Monogr. 71, 557–585 (2001).

Scheiter, S., Langan, L. & Higgins, S. I. Next-generation dynamic global vegetation models: learning from community ecology. N. Phytol. 198, 957–969 (2013).

Forrester, D. I., England, J. R., Paul, K. I. & Roxburgh, S. H. Sensitivity analysis of the FullCAM model: Context dependency and implications for model development to predict Australia’s forest carbon stocks. Ecol. Model. 489, 110631 (2024).

Case studies forestry and urban tree management projects. dimap (accessed 5 December 2025); https://dimap.asia/forestry-tasmania-usage-of-full-waveform-lidar-in-forestry-taxation/

Anderson-Teixeira, K. J. et al. CTFS-ForestGEO: a worldwide network monitoring forests in an era of global change. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 528–549 (2015).

Allen, R. G., Pereira, L. S., Raes, D. & Smith, M. FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56. Vol. 56, article e156 (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1998).

Prentice, I. C., Villegas-Diaz, R. & Harrison, S. P. Accounting for atmospheric carbon dioxide variations in pollen-based reconstruction of past hydroclimates. Glob. Planet. Change 211, 103790 (2022).

Abatzoglou, J. T., Dobrowski, S. Z., Parks, S. A. & Hegewisch, K. C. Data Descriptor: TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958-2015. Sci. Data 5, 170191 (2018).

Australian Government. National Vegetation Information System Data Products (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, accessed 5 December 2025); https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/environment-information-australia/national-vegetation-information-system/data-products

Lynch, A. H. et al. Using the paleorecord to evaluate climate and fire interactions in Australia. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 35, 215–239 (2007).

Falster, D. et al. AusTraits, a curated plant trait database for the Australian flora. Sci. Data 8, 254 (2021).

Sheil, D. & May, R. M. Mortality and recruitment rate evaluations in heterogeneous tropical forests. J. Ecol. 84, 91–100 (1996).

Sheil, D., Burslem, D. F. R. P. & Alder, D. The interpretation and misinterpretation of mortality rate measures. J. Ecol. 83, 331–333 (1995).

Bauman, D. et al. Tropical tree growth sensitivity to climate is driven by species intrinsic growth rate and leaf traits. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 1414–1432 (2022).

Prior, L. D. & Bowman, D. M. J. S. Big eucalypts grow more slowly in a warm climate: evidence of an interaction between tree size and temperature. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 2793–2799 (2014).

Prior, L. D. & Bowman, D. M. Across a macro-ecological gradient forest competition is strongest at the most productive sites. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 260 (2014).

Phillips, O. L. et al. Pattern and process in Amazon tree turnover, 1976–2001. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 359, 381–407 (2004).

Muller-Landau, H. C., Detto, M., Chisholm, R. A., Hubbell, S. P. & Condit, R. Detecting and projecting changes in forest biomass from plot data. For. Glob. Change 17, 381–416 (2014).

Trouvé, R. & Robinson, A. P. Estimating consignment-level infestation rates from the proportion of consignment that failed border inspection: possibilities and limitations in the presence of overdispersed data. Risk Anal. 41, 992–1003 (2021).

Bowman, D. M. J. S., Brienen, R. J. W., Gloor, E., Phillips, O. L. & Prior, L. D. Detecting trends in tree growth: not so simple. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 11–17 (2013).

Trouvé, R., Bontemps, J.-D., Collet, C., Seynave, I. & Lebourgeois, F. When do dendrometric rules fail? Insights from 20 years of experimental thinnings on sessile oak in the GIS Coop network. Ecol. Manag. 433, 276–286 (2019).

Lu, R. et al. Pervasive increase in tree mortality across the Australian continent. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28407893 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank all collaborators, including those not listed as coauthors, for supporting this work and for their contributions to data collection and management. We thank the Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network (Daintree Rainforest, Cow Bay and Robson Creek Supersites) and individual scientists, including Lucas Cernusak and Susan Laurance (James Cook University, QLD), for making their measurements openly accessible. The legacy and contribution of past Queensland Government Forestry Departments and staff in data collection, collation and maintenance of QLD Native Forest Permanent Plot data since 1941 is gratefully acknowledged. We thank H. Murphy (CSIRO) for assistance with the QPRP-CSIRO dataset. We acknowledge that the QPRP-CSIRO data is the long-term work of CSIRO staff. We encourage prospective investigators to inform the principal investigators of their intent to use these data in publications. We acknowledge the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action, Victoria, for contributing the Victorian Forest Monitoring Program data. We acknowledge the former VicForests for contributing the Victorian Permanent Growth Plot dataset. For Western Australian data, we thank the Forest Management Branch, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions and predecessors, especially the work of L. McCaw, M. Rayner and R. Breidahl. R.L. and J.X. were supported by National Key R&D Program of China (grant no. 2022YFF0802104), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 32325033) and Shanghai Pilot Program for Basic Research (grant no. TQ20220102). The Forest Industries Climate Change Research Fund grant from the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (project no. B0018298 DAFF) to D. Bowman supported the initial collation of much of the data used in this study. R.T. was funded by an Australian Research Council Discovery Project (grant no. DP220103711). B.E.M. and L.J.W. were supported by an Australian Research Council Laureate Fellowship (grant no. FL190100003) awarded to B.E.M.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.E.M. initially conceptualized the study. B.P.M., H.C., P.T.G., M.J.L., C.M., D.M., R.M., M.R.N., V.J.N., K.R. and S.S. contributed data and assisted in their interpretation. L.J.W. and B.E.M. collated the datasets with assistance from L.P., P.J.B., D.I.F. and R.T. R.L. harmonized the datasets; led the data analysis with assistance from R.T., L.J.W. and B.E.M; and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revisions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Plants thanks Roel Brienen and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Temporal pattern of tree mortality rate across four major biomes in Australia.

Temporal trajectories of annual tree mortality rate across four major forest biomes: a, tropical savanna; b, tropical rainforest; c, warm temperate forest; and d, cool temperate forest. Solid lines show mean annual mortality rate, and shaded bands indicate 95% confidence intervals based on 1,000 bootstrap resamples per year.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Temporal variation in plot number, mean plot area, and census interval across four major biomes in Australia.

Changes over time in the number of plots, mean plot area, and census interval for four Australian biomes. Colors denote tropical savannas (orange), tropical rainforests (green), warm temperate forests (purple), and cool temperate forests (blue).

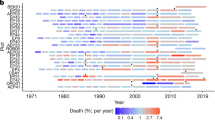

Extended Data Fig. 3 Plot-level tree mortality trends across four major forest biomes in Australia.

Annual change in mortality rate for individual plots in a, tropical savanna; b, tropical rainforest; c, warm temperate forest; and d, cool temperate forest. Analyses include only plots with ≥3 censuses (sample sizes: 158 of 198, 24 of 25, 895 of 1,168, and 822 of 1,333, respectively). Random-slope models were fitted to estimate within-plot changes through time, and the annual change in mortality rate was approximated as exp(β) − 1, where β is the year coefficient (see Supplementary Methods 1). Plots with β values outside the range -0.5 to 2 were excluded to avoid extreme fits.

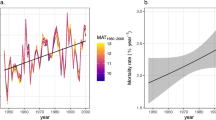

Extended Data Fig. 4 Temporal trends in annual maximum temperature across four major forest biomes in Australia.

Points show the annual mean maximum temperature averaged across plots for a, tropical savanna; b, tropical rainforest; c, warm temperate forest; and d, cool temperate forest. Solid lines show the temporal trends predicted by the linear mixed-effects model (Model 7).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Temporal trends in annual mean vapor pressure deficit (VPD) across four major forest biomes in Australia.

Points show the annual mean vapor pressure deficit (VPD) averaged across plots for a, tropical savanna; b, tropical rainforest; c, warm temperate forest; and d, cool temperate forest. Solid lines show the temporal trends estimated using a linear mixed-effects model (Model 7).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Temporal trends in drought severity across four major forest biomes in Australia.

Points show the annual minimum Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) averaged across plots for a, tropical savanna; b, tropical rainforest; c, warm temperate forest; and d, cool temperate forest. Solid lines show the temporal trends predicted by the linear mixed-effects model (Model 7). Although SPEI is a relative measure of climatic water balance rather than direct vegetation water loss, sustained negative trends indicate intensifying drought stress and an increasing frequency of extreme drought events.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Trait effects on average mortality rate and temporal change across four major forest biomes in Australia.

Effects of species functional traits on average mortality rate and their temporal changes across biomes. Points show estimated hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for maximum tree height (Hmax), specific leaf area (SLA) and wood density (WD). Traits with positive effects on mortality are shown in red, and those with negative effects in blue. Species numbers were 135 in tropical savannas, 522 in tropical rainforests, 282 in warm temperate forests, and 126 in cool temperate forests.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Principal component analysis (PCA) of species trait distribution.

PCA of species-level mean functional traits. Arrows denote trait loadings, and points represent species mean positions in trait space. Contour lines indicate kernel density of species occurrence, with red showing higher density and yellow lower density.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Predicted mortality patterns across key functional trait gradients.

Modelled temporal mortality patterns across gradients of a, maximum tree height (Hmax); b, specific leaf area (SLA); and c, wood density (WD) for all biomes combined. Shaded bands indicate 95% confidence intervals for fixed effects.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Temporal trends in tree growth rate and determinants across four major forest biomes in Australia.

Temporal patterns of tree growth rate across four major biomes and their dependence on tree- and stand-level characteristics. a, Fixed effects of stand basal area (BA), diameter at breast height (lnDBH), and year on annual tree growth rate. Red and blue triangles denote significant positive and negative effects, respectively. b, Modelled annual tree growth rates over time. Solid lines show significant temporal trends with shaded 95% confidence intervals; dashed lines denote non-significant trends. Trees with DBH > 80 cm (2% of total) were excluded due to nonlinear growth responses not captured by the linear model (see Supplementary Fig. 10).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–11, Discussion and Tables 1–4.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, R., Williams, L.J., Trouvé, R. et al. Pervasive increase in tree mortality across the Australian continent. Nat. Plants 12, 62–73 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-02188-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-02188-2