Abstract

The recent emergence of wearable devices will enable large scale remote brain monitoring. This study investigated whether multimodal wearable sleep recordings could help screening for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Measurements were acquired simultaneously from polysomnography and a wearable device, measuring electroencephalography (EEG) and accelerometry (ACM) in 67 elderly without cognitive symptoms and 35 AD patients. Sleep staging was performed using an AI model (SeqSleepNet), followed by feature extraction from hypnograms and physiological signals. Using these features, a multi-layer perceptron was trained for AD detection, with elastic net identifying key features. The wearable AD detection model achieved an accuracy of 0.90 (0.76 for prodromal AD). Single-channel EEG and ACM physiological features captured sufficient information for AD detection and outperformed the hypnogram features, highlighting these physiological features as promising discriminative markers for AD. We conclude that wearable sleep monitoring augmented by AI shows promise towards non-invasive screening for AD in the older population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Around 50 million people worldwide live with dementia, of which Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the main cause1. This public health problem has a huge economic impact2. Hence, there is an urgent need for sensitive markers to diagnose AD in the early disease stages to facilitate therapeutic interventions.

Sleep changes have been linked to AD pathology, even before cognitive symptoms emerge, endorsing its potential as an early noninvasive diagnostic feature for AD3,4,5,6. In a recent study from Ye et al.7, a machine learning algorithm applied to polysomnography (PSG) was able, to some extent, to distinguish patients with dementia or mild cognitive impairment from cognitively intact elderly (CIE) individuals. Although in-hospital PSG with manual five-class sleep scoring – distinguishing Wake, N1, N2, N3, and REM—is the gold standard for studying sleep, it would be impractical for large-scale screening purposes.

Fortunately, more recently, multimodal wearable devices have emerged as a potential comfortable alternative for sleep monitoring in a home-based environment, with the potential for long-term use. However, the miniaturization, reduced number of electrodes, and unsupervised use can introduce motion artifacts and lower signal quality compared to PSG. This raises the crucial question of whether these devices can capture sleep patterns with sufficient fidelity for automated AD detection.

In addition, wearable devices generate large data volumes, necessitating reliable artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to replace manual PSG-based sleep scoring with automated analysis. In recent years, continuous efforts have focused on improving algorithms to attain expert-level accuracy levels in sleep staging8. However, the majority of these algorithms have been developed and tested on PSG studies of healthy, young adults, neglecting the older and diseased populations that are most challenging, but also most relevant for clinical applications. If we want to implement remote sleep measurements as a non-invasive screening tool for AD, the pivotal question is whether multimodal wearable devices can capture the necessary information. We need to determine if fully automated processing of wearable data can reliably detect individuals with AD in the older population.

To investigate if sleep monitoring with wearable devices can be used as a screening tool for AD on population level, the current study had three main objectives: firstly, to present an AI algorithm for automated sleep staging on AD patients based on a wearable device measuring one-channel electroencephalography (EEG) and accelerometry (ACM), and compare this to gold-standard PSG; secondly, to design an AI-based algorithm that uses sleep features to discriminate AD patients in the prodromal and dementia disease stage from CIE individuals; and thirdly, to identify which sleep features are the most informative parameters for detecting AD.

Results

Datasets and population characteristics

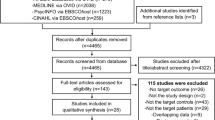

For this method-development and proof-of-concept study (Fig. 1), the dataset was derived from two cross-sectional studies (Fig. 1A), both encompassing overnight PSG simultaneously acquired with measurements from a two-channel behind-the-ear wearable EEG device which also had an ACM, called the SensorDot (Byteflies, Antwerp, Belgium) (Fig. 1B, C). Data was collected between September 2019 and December 2022. The first dataset (n = 82) comprised participants between 60 and 79 years old who underwent in-hospital PSG for suspected sleep apnea and shall be further referred to as the Senior Sleep Dataset (Table 1)9,10. The second dataset (n = 65), further referred to as the Alzheimer’s Sleep Dataset, was obtained in a home-based environment and comprised patients with AD and control participants between 55 and 85 years old (Table 2)11. Technical details and extended dataset details are available in the “Methods”.

A The datasets used for this study. The Senior Sleep Dataset (n = 82) and Alzheimer’s Sleep Dataset (n = 65) consist of in-hospital and home-based acquired sleep studies, respectively. B Technical set-up. PSG was simultaneous acquired with a wearable EEG device. C Detailed technical set-up of the wearable device. The device is placed in the neck. Two electrodes are attached behind one ear, and one electrode behind the opposite ear, creating a cross-head and ipsilateral EEG channel. The wearable EEG device also has an ACM in it. D A schematic representation of the methodology. The annotated PSG by the clinician was used as a ground truth. An automated sleep staging AI model was developed on the wearable data. Hypnogram and physiological features (EEG and accelerometry signals) from this AI-model were used for the AD detection MLP model in order to distinguish patients with AD from CIE. Parts of the figure were modified from Byteflies. Abbreviations: ACM accelerometry, AD Alzheimer’s disease, AI artificial intelligence, all all sleep stages, CIE cognitively intact elderly, PSG polysomnography, STD standard deviation. Abbreviations for hypnogram features are explained in Supplementary.

From the combined dataset, thirty-five participants were diagnosed with either clinical probable (n = 7) or biomarker proven (n = 28) AD12,13 (Supplementary Table 1). Twelve patients with AD had an MMSE ≥ 27/3014 and were further classified as prodromal AD (biomarker proven: n = 9; clinical probable: n = 3). The remaining 112 participants were free of subjective and/or objective cognitive symptoms and were considered CIE. The combined dataset (n = 147) was divided in a training (n = 45) and test dataset (n = 102), of which the former was only used for training a sleep staging model, and the latter, described in Table 3, was used for all subsequent analyses, including cross-validation of the AD detection models.

Sleep staging

SeqSleepNet15, a state-of-the-art AI model for automated sleep staging, was trained to score both the PSG and two channels of the wearable data: the cross-head EEG and ACM (Fig. 1, details in “Methods”). The overall performance of the five-class sleep staging model was 65.5% on the multimodal wearable device, with a Cohen’s kappa score of 0.498, indicating moderate agreement. This was an absolute 11.4% lower than the model performing sleep staging on PSG, and it could be improved by 4.8% by further fine-tuning of the model (Supplementary Table 2). In the rest of this paper, AI scoring refers to sleep staging performed by the SeqSleepNet model.

Detection of patients with AD

Two sets of sleep features were calculated based on the sleep stages and the measured signals: hypnogram features and physiological features (see “Methods”). To assess the diagnostic potential of both features in discriminating AD from CIE, we employed a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) to detect AD. We aimed to evaluate AD detection performance using wearable data scored by AI (the SeqSleepNet sleep staging model) in comparison to two baselines: PSG scored by AI, and PSG scored by a certified scorer. Therefore, both the hypnogram and physiological features were calculated with three approaches: using the PSG with manual (ground truth) sleep scoring, using the PSG with AI scoring, and using the wearable data with AI scoring.

Figure 2 shows the ROC curves of the AD classification results. Each panel shows the ROC curves for the ability to discriminate all AD patients from CIE, and for the patients in the prodromal AD stage from the CIE. The physiological features (Fig. 2d–f) outperformed the hypnogram features (Fig. 2a–c) by far in every scenario, with differences in AUC of 0.26–0.37.

The transparent lines represent the ROC curves of all ten cross-validation runs for each prediction task, while the non-transparent lines represent the ROC curves obtained using the mean predictions with these ten repeats. Their AUC is reported in the legend. As the prodromal AD patients are a subgroup of AD, the curves labeled with “AD” show the performance in discriminating CIE patients from the whole AD cohort, consisting of patients in the prodromal and dementia disease stage. The curves labeled with “prodromal” show the performance in discriminating the prodromal AD patients from the CIE group. The upper row shows the performances using hypnogram features, calculated based on a the manually scored PSG, which is the ground truth, (b) the AI-scored PSG, (c) the AI-scored wearable data. The lower row shows the performances using the physiological features, calculated based on both the raw data and sleep stage labels. In (d), the PSG data was used with manual labels, in (e), the PSG data was used with AI-scored labels, and in (f), the wearable data was used with AI-scored labels. The ROC curves show that the physiological features by far outperform the hypnogram features. For the physiological features, the features derived with AI scoring (based on both PSG and wearable) are almost on par with the features based on ground truth scoring. AD Alzheimer’s disease, AI artificial intelligence, AUC area under the curve, CIE cognitively intact elderly, PSG polysomnography, ROC receiver operating characteristic.

Despite imperfect sleep staging, the classification performance with physiological features derived with AI scoring, both PSG- and wearable-based, was almost on par with features derived from human sleep staging. Strikingly, based on a wearable with only one channel of EEG and ACM, scored with AI, our MLP was able to detect patients with AD with an AUC of 0.90, and specifically prodromal AD patients with AUC 0.76. The performance as measured by AUC was similar for the MLP based on AI-scored PSG with five channels (3 EEG, EOG, and EMG). Training a classifier on the combined set of the hypnogram and physiological features did not improve the performance.

To investigate whether sleep staging contributes to feature effectiveness, we tested an alternative approach for the physiological features, that bypassed staging by aggregating frequency content across the entire night (Fig. 3). This modified set of physiological features without sleep staging yielded slightly lower AUCs than our staging-based approach, suggesting that sleep staging helps organize the EEG features into more meaningful bins. However, these modified physiological features still provided significantly better classification than hypnogram-based features alone, reinforcing the importance of EEG-derived information in AD detection.

These results show the AD detection performance when using as features the frequency bands for the different channels (both mean and STD) but aggregating them over the whole night without sleep staging. The transparent lines represent the ROC curves of all ten classifiers trained for each prediction task, while the non-transparent lines represent the ROC curves obtained using the mean predictions with ten repeats. Their AUC is reported in the legend. The curves show the performances using (a), the raw PSG data, and (b), the raw wearable data. AD Alzheimer’s disease, AUC area under the curve, OSA obstructive sleep apnea, PSG polysomnography, ROC receiver operating characteristic.

As OSA is associated with sleep disruption, we also compared the performance in detecting AD patients with and without OSA and found similar AD detection performances for both groups (Supplementary Fig. 2). We also tested whether age influenced the performance since the patients with AD were slightly older compared to the CIE. Overall, the MLP model could slightly better detect patients with AD > 75 years old compared to those ≤75 years old from the CIE, with exception for the MLP model based on the wearable-based AI-scored hypnogram features which performed worse in the elderly age group, reflecting the more difficult traditional five-class sleep scoring in this particular age group (Supplementary Fig. 3). Additional performance metrics were also computed (Supplementary Table 4).

Insights into the features and feature selection

To gain deeper insight into the sleep features’ relation to AD and explore their clinical significance, we performed two distinct analyses: a correlation analysis with Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score14 and a feature importance analysis based on feature selection.

Firstly, the sleep features’ clinical relevance was assessed by computing the Pearson correlation with MMSE for all hypnogram features as well as for a small subset of physiological features. Fig. 4 shows the Pearson correlations between the MMSE score and the sleep features based on wearable data. From the ground truth hypnogram features, the four most selected were mean time between consecutive REM bouts, number of transitions to N3 divided by total sleep time, wake after sleep onset (WASO), and mean N3 bout duration (N3BoutDuration). For the hypnogram features based on wearable data and AI scoring, the amount of N2 and REM were the most informative, along with the number of transitions to REM and N3BoutDuration. We concluded from the hypnogram features that indicators of AD in the sleep architecture were mainly the distribution of N3 and REM (including number of transitions and bout durations), as well as WASO, and amount of light sleep. Based on ground truth scoring, 42.9% of the hypnogram features and 32.2% of the physiological features showed significant correlations with MMSE. The features based on wearable data and AI scoring matched the significant correlations of the ground truth hypnogram and physiological features in 64.7% and 82.2% of the cases, respectively. Utilizing PSG data, the concordance between features based on AI-scoring and based on ground truth scoring was even higher than for the wearable data (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The hypnogram features are shown in the upper part of the figure, and a few selected physiological features are shown in the lower part. The first column shows the ground truth sleep features based on the wearable data, but scored with the ground truth manual PSG scoring, and the second column shows sleep features based on the wearable data scored by AI. Pearson’s correlation test was performed, with the subjects as samples. The MMSE score was not recorded in the patients from the Senior Sleep Dataset, so the correlations are only computed for the 65 patients of the Alzheimer’s Sleep Dataset (see Table 2). Correlations are shown through the colors, with p values below 0.05 reported as numbers to indicate the significance of the correlations. The wearable-based features based on AI scoring and based on ground truth scoring agree on most significant correlations. ACM accelerometry, AI artificial intelligence, All all sleep stages, EEG electroencephalography, MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination, STD standard deviation. Abbreviations for hypnogram features are explained in Supplementary Table 1.

Secondly, we trained the MLP with elastic net feature selection, identifying the most informative features for AD detection with ten leave-one-out cross-validation runs and reporting the most frequently selected ones. Figure 5 displays physiological features that were selected more than 85% of times by the AD detection model based on the wearable data (Fig. 5a) and PSG data (Fig. 5b). The wearable-based feature selection indicated that important EEG features included 9–11 Hz in Wake, 4–5 Hz in N1, 9–10 Hz in N2, and 0–1 Hz in REM. Derived from PSG, the most important EEG features included 4–6 Hz in Wake, 1–2 Hz and 7–8 Hz in both N1 and N2, 0–1 Hz and 11–14 Hz in N3, and 0–1 Hz in electrooculography (EOG) in REM. From the wearable’s ACM and PSG’s electromyography (EMG), features were selected in Wake, N1, and the whole recording. From both the wearable and the PSG, we can conclude that the alpha and theta EEG band in wakefulness and light sleep are helpful to detect AD, as well as slow activity during REM. Additionally, slow delta activity (0–2 Hz) in non-REM sleep also holds discriminative power, although this was only picked up on PSG. A comparison between features selected using ground truth and AI scoring highlighted imperfections in sleep staging, but confirmed that key features remained identifiable and valuable for AD detection (Supplementary Fig. 5).

The features that were selected more than 85% of the time by the a wearable-based and b PSG-based AD detection model. In both cases, the features were calculated using ground truth sleep scoring (for the features calculated using AI scoring, see Supplementary Fig. 5). Features are visualized using three rings showing to which (1) sleep stage, (2) channel, and (3) frequency range each feature corresponds. The frequency range is only shown for the EEG and EOG channels due to the limited interpretability of the EMG and ACM frequencies. The discrete color bar shows the interpretation of the frequency range. The surrounding black ring shows which features were computed using STD, with the remaining calculated using the mean. The width of each segment indicates how many features of that type were selected more than 85% of the times. This width should not be mistaken for overall importance of a channel or sleep stage: information may be more spread out over multiple frequency bands for some channels or sleep stages than for others. Rather, this figure shows which channels are important in which sleep stages, and which frequencies were decisive in those channels. ACM accelerometry, AD Alzheimer’s disease, AI artificial intelligence, All features computed over the whole recording, EEG electroencephalography, EOG electrooculography, EMG electromyography, PSG polysomnography, STD standard deviation.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the viability of wearable automatic sleep monitoring in the elderly population, specifically towards screening for AD. For the first time, we developed a screening tool for AD using a multimodal wearable device that measures single-channel EEG and ACM. This fully automated AI pipeline includes: (1) AI-based sleep scoring to extract relevant sleep features, and (2) an MLP model leveraging these features for AD detection. We validated our pipeline on both PSG and wearable device, showcasing its versatility across hospital and home environments. To gain insight into the sleep features most predictive for AD, we investigated which features correlated most with MMSE and which were most frequently selected by elastic net feature selection for AD detection.

A unique feature of our study is that we distinguished patients with AD from older individuals without cognitive complaints based on measurements from a wearable device. With the objective of large-scale home-based AD screening in mind, we designed a fully automated AI pipeline for this purpose. With an AUC of 0.90, our wearable-based AI pipeline demonstrated excellent performance for AD detection (see Fig. 2f). This was especially remarkable as we included sleep apnea as a potential confounder. The results were on par with the performance in detecting AD with the same AI pipeline based on PSG measurements (see Fig. 2e). This shows that single-channel EEG with ACM may be sufficient for AD detection, and that perfect sleep staging is not needed to achieve a useful screening tool. When using physiological features, sleep staging primarily served to delineate bins for averaging the spectral content of measured signals. Hence, the spectral content itself was more important than how it was categorized into sleep stages. Conversely, for hypnogram features, the accuracy of sleep staging played a more pivotal role, as was expected. This was evidenced by the larger performance difference between features derived from manual and automatic scoring. Our performances were higher compared to those of the dementia detector from Ye et al.7, even though they relied on manually scored PSG. First, the difference might be explained by different features used: they only relied on averages of EEG variables, whereas we found variability of the features to be more informative. Second, we specifically aimed to detect AD, while their study focused on dementia of all types. Although their model was developed on a larger PSG sample, they included diagnostic and CPAP titration PSGs from the same individuals and there was a greater class imbalance, which may have influenced their results.

When training our MLP classification model to specifically detect the subgroup of patients in the prodromal disease stage, the AUC dropped to 0.84 for the PSG-based classifier and to 0.76 for the wearable-based classifier. A drop in performance was expected for two reasons. First, sleep and EEG alterations become more pronounced as AD progresses16,17, as evidenced by the correlations with MMSE scores (Fig. 4)18. Second, the MLP model only had a limited number of examples of prodromal AD to learn from (only 12 prodromal AD subjects). Training the model on a larger sample of prodromal AD patients should increase the performance.

The most informative hypnogram features to distinguish AD from CIE were very similar between the ground truth and wearable-based AI scoring. Features related to N3, REM, and WASO were most relevant. Of the wearable-based AI-scored features, an increased N2 was selected as well, likely due to the algorithm confusing REM for N2 in AD patients. Overall, the selected hypnogram features reflect the macrostructural sleep changes observed in AD, consistent with literature11,16,18.

The most valuable physiological features derived from the PSG data (Fig. 5), using ground truth sleep scoring, ensued from all sleep stages, with EEG frequencies around 0–2 Hz, 4–6 Hz, 7–8 Hz, and 11–14 Hz being most selected. Very similar observations were made based on the wearable data. Out of all physiological wearable-based features using ground truth scoring, the most informative EEG features were mainly found in wakefulness, light sleep, and REM. Overall, these features are congruent with the most important features from the model of Ye et al.7 and reflect an increased slowing of the EEG, consistent with the microstructural sleep alterations, which are small changes in EEG frequency (such as a reduction of sleep spindles and EEG slowing during REM and wakefulness), observed in AD17,19,20.

Interestingly, the physiological features outperformed the hypnogram features for both PSG and wearable data. Combining the two feature sets did not help the MLP-based AD classifier to achieve a higher accuracy, and even the hypnogram features based on manual scoring demonstrated inferior performance compared to the physiological features based on the wearable with AI scoring. For prodromal AD detection, the difference was even more pronounced, with near-chance-level accuracies achieved based on hypnogram features. Microstructural sleep changes without obvious macrostructural sleep changes have been observed in the prodromal disease stage17,19. In addition, the performance of the AD detection model was less affected by OSA or age for the physiological features compared to the hypnogram features (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3c, f). Overall, this might indicate that microstructural sleep alterations, as reflected in the physiological EEG features, could be considered as more promising biomarkers for detecting patients with AD compared to macrostructural changes, especially in the early disease stages.

The PSG- and wearable-based AI model for automatic sleep scoring reached an accuracy of 76.9% and 65.5%, respectively, compared to gold standard manual PSG scoring. This difference in accuracy was not surprising as we went from five channels to two channels, omitting EOG, EMG, and 2 channels of EEG. Furthermore, various physiological signals, such as eye-, jaw-, and head movements, can introduce artifacts, with jaw movements as most important source for ear electrodes21. A direct comparison of different setups, such as headbands and C-shaped around-the-ear electrode arrays, could help optimize both accuracy and usability across wearable EEG designs22. The sleep stage that was mostly responsible for this drop in performance was REM. In retrospect, recording a second channel at F7 or F8 to detect eye movements may have improved REM sleep detection. Although REM was still scored well in CIE patients, the performance drop was large in patients with AD, where REM was frequently misclassified as N2. This could be attributed to the REM slowing, which is often present in AD17,19,20. The 65.5% accuracy for five-class sleep scoring was slightly lower compared to previous studies on one- or two-channel EEG recordings8, but those studies were conducted in smaller samples consisting of healthy younger individuals. The presence of OSA and AD in our dataset, alongside a more advanced age, are associated with a more disrupted sleep16,18,23, which is more difficult to score. This was shown by the 5% increase in accuracy when evaluating our sleep staging model on the CIE subgroup without OSA (Supplementary Table 2). We conclude that sleep staging performance is influenced by numerous factors related to patient demographics. However, sleep staging should not be the sole focus of automated sleep analysis, as we showed that the resulting sleep parameters can effectively detect AD with comparable accuracy, even with the sleep staging accuracy varying from 65.5% to 76.9%.

Based on our results, this study holds potential implications for public health and avenues for future research. Firstly, consistent with previous studies8, we demonstrated that one-channel EEG devices can present a reliable, comfortable alternative compared to the cumbersome gold-standard PSG, and, consequently, could be applied for longitudinal home-based sleep monitoring. Secondly, now that we have established that AI algorithms can detect prodromal AD based on wearable sleep measurements, it would be useful to extend this research to large home-based cohorts in the preclinical AD stage. If successful, we can apply sleep measurements as a screening tool to detect patients in the preclinical AD stage, which in turn might offer opportunities for therapeutic trials. Thirdly, since the physiological features were more sensitive than the hypnogram features, future sleep studies should deploy AI approaches that identify microstructural sleep changes. Fourthly, sleep disturbances and epilepsy have an increased prevalence in AD. Decreased REM, a potential epilepsy biomarker, could be monitored in AD using a wearable device10,24.

Our study sample had some limitations. First, the criteria used to define CIE differed for both datasets used. For the Senior Sleep Dataset9,10, we retrospectively searched the electronic health records for reported cognitive complaints, excluding participants with such complaints. In a subsample, no information about cognitive function was available. For both datasets, no neuroimaging or CSF biomarkers were available for the participants considered CIE, so preclinical AD could not be ruled out. Secondly, patients with AD were slightly older compared to the CIE. Additional analysis demonstrated that the MLP-based AD detection model performed slightly better in the elderly age group, both for the hypnogram and physiological features. Only the MLP classifier using wearable-based AI-estimated hypnogram features performed worse in the elderly age group. This might indicate that it’s more difficult to obtain reliable wearable-based estimated hypnogram features in the elderly age group. Testing the AD classification performance in more distinct age categories might aid in the appropriate model choice for future research. Third, the senior sleep dataset was acquired in-hospital, while the Alzheimer’s Sleep Dataset consisted of home-based recordings. Hence, the environmental factors in both datasets are not identical, which may slightly influence the results. Despite the limitations inherent to this study sample, a main strength of this sample was the fact that it consisted exclusively of participants above 55 years old with a balanced ratio of patients with OSA and a large proportion of patients with AD. By incorporating challenges posed by OSA and older age, known risk factors for AD, and obstacles for automated sleep staging algorithms, we constructed a sample reflecting real-world complexities. While larger sample sizes are warranted for future validation of our AD detection method, our algorithm development on this representative population enables reliable extrapolation to a large-scale home-based study. Another strength of this study was the fully automated nature of the proposed method and its suitability for home-based monitoring. Whereas previous studies have relied on full-scalp EEG or PSG with manual sleep scoring, our automated, wearable approach represents a significant advancement towards integrating sleep as a screening tool in future clinical practice.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that AI algorithms allow to discriminate patients with AD from CIE individuals based on sleep measurements, taking OSA into consideration. Physiological features, specifically those related to EEG slowing in wakefulness, light sleep, and REM, and a decrease in slow wave activity during N3, are the most informative diagnostic features for AD. In addition, with an AD classification model trained on data from a wearable device, we demonstrated that one-channel wearable EEG and ACM contain sufficient information and that perfect five-class sleep scoring is not required for AD detection. Further refinement of our proposed method in larger prodromal AD cohorts, along with extension to the preclinical AD population, offer promising avenues for early AD screening in older adults.

Methods

Dataset details

The Senior Sleep Dataset (Table 1), sourced from the senior sleep study9,25, originally comprised 90 in-hospital PSG recordings along with wearable device data from participants above 60 years old suspected for sleep apnea (OSA). A portion (n = 45) of the Senior Sleep Dataset was used as a training dataset (to pre-train our sleep staging algorithm). The rest was pooled with the Alzheimer’s Sleep Dataset as a test dataset, for evaluating the sleep staging performance and for training and testing an AD detection model. Cross-head EEG recordings collected with the wearable device were available in all participants, except for the training dataset (n = 45). Instead, in these patients, behind-the-ear EEG data were collected with standard EEG equipment, simulating the wearable EEG recordings. Clinical data extraction from medical records revealed that 18 participants of the Senior Sleep Study reported subjective cognitive complaints, 8 of whom were part of our test dataset. Subsequently, these eight individuals were excluded to eliminate ambiguity concerning AD. Of the 72 participants without subjective cognitive complaints, sixteen had no subjective cognitive complaints, and for the other 56, no information about subjective or objective cognitive functioning was available in the medical record.

The Alzheimer’s Sleep Dataset (Table 2) was sourced from a prior observational cross-sectional study on AD and sleep11. Eligible recordings, encompassing home-based overnight PSG simultaneously acquired with the wearable device, were selected from 30 control subjects and 35 patients with either probable clinical AD (n = 7) or biomarker proven AD dementia (n = 28)12,13. Details are shown in Supplementary Table 2. Thirty-four percent of patients with AD had an MMSE14 ≥ 27/30 and were further classified as being in the prodromal AD stage. Control subjects in this dataset were defined as healthy volunteers, free of subjective cognitive decline, with an MMSE ≥ 27/30, and a Clinical Dementia Rating scale26 score of 0.

Technical setup of the PSG recordings and wearable device

PSGs from the Senior Sleep Dataset were conducted in the hospital following the recommended American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) guidelines version 2.627. The PSGs from the Alzheimer’s Sleep Dataset were conducted at-home with a slightly different set-up: scalp electrodes were placed using the International 10–20 system with additional lower temporal electrodes (F9, F10, T9, T10, P9, P10) without P3 and P4, and Cz was used as the ground. Additional sensors for PSG included EOG1/2, chin EMG, nasal flow (NAF2P), thoracic and abdominal resistance bands, finger pulse oximetry, ECG derivation Eindhoven I, and EMG of one leg. Finally, a camera with audio recorder was installed in the patient’s bedroom for nighttime activity recording. In this dataset, electrodes P9/10 were used as reference electrode instead of A1/2, and apneas were scored based on the flow signal on NAF2P. PSG recordings from both datasets were scored from lights-off until lights-on conform the AASM scoring rules version 2.627. Those annotations were used as ground truth. The presence of sleep apnea was defined as an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 15/h. PSG recordings were acquired with Medatec software (Medical Data Technology, Braine-le-Château, Belgium), using a sampling rate of 200 Hz. The wearable device consisted of a small (24·5 × 33·5 × 7·73 mm; 6·3 g) biopotential amplifier. It was placed in the neck, with one electrode behind the first ear, and two electrodes behind the other, creating a two-channel EEG with one cross-head and one unilateral channel (Fig. 1). It also has an inherent ACM. EEG and ACM data were measured at sampling rate of 250 and 50 Hz, respectively. Only the cross-head EEG channel and ACM data were used.

Sleep staging model

We employed SeqSleepNet to perform automated sleep staging. This is a state-of-the-art sleep staging model15 characterized by a sequence-to-sequence classification approach. This deep neural network transforms sequences of contiguous raw data segments into a corresponding sequences of sleep stages. Spectrograms of the 30-second segments served as two-dimensional inputs. We fixed the sequence length to 10 (the equivalent of 5 min) in this study. The SeqSleepNet architecture consists of two main blocks: a segment processing block and a sequence processing block. The segment processing block features frequency filters and a recurrent neural network (RNN). Its outputs are concatenated to form inputs for the sequence processing block. A sequence-level RNN converts this sequence into a corresponding output sequence, which a softmax layer then maps to a sleep stage sequence. Training parameters and optimization strategies followed the specifications outlined in the original paper15, including the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 10−4, L2 regularization, and early stopping by use of a validation set.

SeqSleepNet was trained for sleep staging on both the PSG data and wearable data of our datasets. The manual annotated PSG was used as a ground truth. The PSG-based model used five channels of the PSG data: the C4-P9, F4-P9, O2-P9, chin EMG1-2, and EOGleft-EOGright. For the wearable-based model, we used 2 channels: the cross-head EEG channel and the ACM channel. The wearable data were aligned with the PSG data by using the cross-correlation between EEG signals. All signals were resampled to 100 Hz. Then, they were short-time Fourier transformed (STFT), using a Hamming window, 256-point Fast Fourier Transform, with a window size of 2 s and 1-second overlap, before feeding them to the model.

Both for sleep staging on the PSG and wearable data, the model was pre-trained on the 45 recordings of the training set from the senior sleep study for 10 training epochs. The reason for choosing this dataset for training was to maximize the similarity of the measurement setups between the training and test dataset for sleep staging. The pre-trained model was directly applied to score the entire test dataset for subsequent feature calculation and AD detection. Additionally, to assess the maximum sleep staging performance across the patient subgroups, we fine-tuned the model on the test dataset, conducting ten-fold cross-validation. During fine-tuning, all model weights were kept trainable to allow full adaptation to the test data. This process involved training the model for ten additional epochs using the same hyperparameters as in pre-training. We then personalized the model to each individual recording in the test dataset using unsupervised adversarial domain adaptation, following the approach from Heremans et al.10. Hence, the personalization step did not rely on any labels from test patients. Specifically, each individual test recording served as the ‘target dataset,’ while all other recordings formed the ‘source dataset.’ To align feature representations, we employed an adversarial loss that encouraged the model to make the target and source feature distributions indistinguishable. This ensured that the model’s learned features remained domain-invariant across recordings. Optimization parameters followed those in the original paper. In conclusion, the sleep staging results (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1) were based on the sleep scoring by the fine-tuned, personalized models. The rest of the results used the pre-trained models’ scorings. In the rest of this paper, we refer to the automated sleep staging by the pre-trained SeqSleepNet model when we use the term “AI scoring”.

Feature calculation

Based on the sleep stages and the measured signals, we computed two sets of sleep features: hypnogram features and physiological features (Fig. 1). Thirty-four hypnogram features were calculated from the hypnograms, representing macrostructural sleep parameters. Physiological features were spectral features of the measured signals, including EEG and ACM for the wearable. They represented averages of the frequency content per channel, sleep stage, and frequency bin of the raw signals’ spectrogram.

Hypnogram features calculation

Supplementary Table 5 shows all 34 hypnogram features that were calculated. Most features have an obvious definition, except the average timing of different sleep stages (“RelOccX” with X being the sleep stage), which was calculated as:

with y being the annotated sleep stages, and the function where returning the times when y is equal to the sleep stage X.

Physiological features calculation

Physiological features were spectral features of the EEG and other measured signals (EMG and EOG in the case of PSG, and ACM in case of the wearable). They were derived from the STFTs of the raw signals, which were computed with 129 frequency bands (representing frequencies between 0 and 50 Hz). To calculate these features, we generated individual time series for each frequency component within every channel for each subject or recording. In the feature space, we reduced the amount of frequency bins to 18 by averaging features within 1 Hz intervals from 0 to 15 Hz, and within the larger intervals of 15–20 Hz, 20–30 Hz, and 30–50 Hz. Temporally, the time series were aggregated per sleep stage (W, N1, N2, N3, R) and for the total recording, using the mean and standard deviation as aggregate measures. For the PSG, the total amount of physiological features was 1080: the number of frequency bands (18) × the number of channels (5) × the number of sleep stages + 1 (6) × 2, because both the mean and standard deviation were computed for each time series. For the wearable, the number of physiological features was 432: 18 × 2 × 6 × 2.

AD detection model: architecture and training

We trained a classifier to discriminate AD from CIE. For both sets of features (physiological and hypnogram), classification was performed with a MLP with a hidden layer of size 20. An MLP was selected because of its strong ability to model complex, nonlinear relationships, and its capacity to generalize to unseen data, especially in high-dimensional datasets. The rest of the parameters were the standard parameters in the Scikit-learn library28. The optimization was performed for 200 iterations, the batch size was the full dataset, the ReLU activation function was used, the Adam optimizer was used with a learning rate of 10−3. The presence of class imbalance necessitated the consideration of multiple performance metrics. Performance was primarily assessed using ROC-curves and their AUC, with additional computation of accuracy, Cohen’s kappa score, precision, and recall.

Pearson correlation details

We investigated Pearson correlations of sleep features with MMSE to investigate the features’ clinical relevance and to verify whether potential correlations were preserved with AI scoring. The MMSE was only available for the 65 patients from the Alzheimer’s Sleep Dataset (and not for the 37 patients from the Senior Sleep Dataset), so the Pearson correlation was only computed for 65 patients, with the patients being samples in the test. p values under 0.05 were reported.

The correlation test was performed for sleep features based on wearable data with ground truth (PSG-based) scoring and with wearable-based AI scoring (Fig. 4) and for sleep features based on PSG data with PSG-based ground truth scoring and with PSG-based AI scoring (Supplementary Fig. 3). The ground truth hypnogram features in both the wearable and PSG results are the same, as they only depend on the scoring (the ground truth scoring being the manual PSG scoring), whereas the ground truth physiological features are different for the wearable and PSG results, because they are based on both the scoring and the data.

Feature selection details

Elastic net feature selection is an embedded feature selection method, which means that the model learns the importance of features while it gets trained. This feature selection method was chosen because of the highly correlated nature of the feature sets. We performed feature selection for both the hypnogram and physiological features, with a standard L1-ratio of 0.5. The regularization strength alpha was determined by conducting grid search on each cross-validation training set, to determine the best alpha value in the range of 10−5 to 10. Ten leave-one-out cross-validation runs led to a total of 10 × 110 iterations of feature selection for each feature set. Only features selected more than 85% of times were reported.

Feature selection was solely used to determine which features were most informative in this study. As the AD classification performance did not consistently benefit from using feature selection, we reported the AD detection results without feature selection.

For the hypnogram features, feature selection was performed on three sets of features: (1) the features based on ground truth scoring, (2) the features based on AI scoring on wearable data, and (3) the features based on AI scoring on PSG data. The results for all three feature sets were reported in the main text. For the physiological features, four sets of features were considered: (1) the features based on PSG data and ground truth scoring, (2) the features based on PSG data and PSG-based AI scoring, (3) the features based on wearable data and ground truth (PSG-based) scoring, and (4) the features based on wearable data and wearable-based AI scoring. The results for all four feature sets were reported in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Statistics implementation

All modeling, analysis, and statistics were performed in Python (version 3.7.9). The SciPy toolbox29, version 1.6.2, was used as to compute the t-tests and Pearson correlations. The Scikit-learn library28 (version 0.23.2) was used for training the AD detection MLP, and TensorFlow30 (version 1.15.0) was used for training the deep learning sleep staging model.

Data availability

Research data collected for this study can be made available upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Code is available upon request.

References

Scheltens, P. et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 397, 1577–1590 (2021).

Georges J., Miller O. & Bintener, C. Dementia in Europe Yearbook 2019: Estimating The Prevalence Of Dementia In Europe, accessed 17 Apr 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339401240_Estimating_the_prevalence_of_dementia_in_Europe (Alzheimer Europe, 2020).

Lucey, B. P. et al. Reduced non-rapid eye movement sleep is associated with tau pathology in early Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaau6550 (2019).

Winer, J. R. et al. Sleep as a potential biomarker of Tau and β-amyloid burden in the human brain. J. Neurosci. 39, 6315–6324 (2019).

Mander, B. A., Winer, J. R., Jagust, W. J. & Walker, M. P. Sleep: a novel mechanistic pathway, biomarker, and treatment target in the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease?. Trends Neurosci. 39, 552–566 (2016).

Lim, A. S. P. et al. Sleep fragmentation and the risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline in older persons. Sleep 36, 1027–1032 (2013).

Ye, E. M. et al. Dementia detection from brain activity during sleep. Sleep. 46, zsac286 (2023).

Imtiaz, S. A. A systematic review of sensing technologies for wearable sleep staging. Sensors 21, 1562 (2021).

Heremans, E. R. M. et al. Automated remote sleep monitoring needs machine learning with uncertainty quantification. J Sleep Res 34, e14300 (2023).

Heremans, E. R. M. et al. U-PASS: An uncertainty-guided deep learning pipeline for automated sleep staging. Comput. Biol. Med. 171, 108205 (2024).

Devulder, A. et al. Subclinical epileptiform activity and sleep disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behav. 13, e3306 (2023).

McKhann, G. M. et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 7, 263–269 (2011).

Albert, M. S. et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 7, 270–279 (2011).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12, 189–198 (1975).

Phan, H. et al. SeqSleepNet: End-to-End Hierarchical Recurrent Neural Network for Sequence-to-Sequence Automatic Sleep Staging. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 27, 400–410 (2019).

Romanella, S. M. et al. The sleep side of aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep. Med. 77, 209–225 (2021).

D’Atri, A. et al. EEG alterations during wake and sleep in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. iScience 24, 102386 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Sleep in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of polysomnographic findings. Transl. Psychiatry 12, 136 (2022).

Brayet, P. et al. Quantitative EEG of rapid-eye-movement sleep: a marker of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 47, 134–141 (2016).

Lam, A. K. F. et al. EEG slowing during REM sleep in older adults with subjective cognitive impairment and mild cognitive impairment. Sleep. 47, zsae051 (2024).

Kappel, S. L., Looney, D., Mandic, D. P. & Kidmose, P. Physiological artifacts in scalp EEG and ear-EEG. Biomed. Eng. Online 16, 103 (2017).

Kaongoen, N. et al. The future of wearable EEG: a review of ear-EEG technology and its applications. J. Neural Eng. 20, 051002 (2023).

Jordan, A. S., McSharry, D. G. & Malhotra, A. Adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet 383, 736–747 (2014).

Ikoma, Y., Takahashi, Y., Sasaki, D. & Matsui, K. Properties of REM sleep alterations with epilepsy. Brain 146, 2431–2442 (2023).

Heremans, E. R. M. et al. From unsupervised to semi-supervised adversarial domain adaptation in electroencephalography-based sleep staging. J. Neural Eng. 19, 036044 (2022).

Huang, H. C. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale for detecting mild cognitive impairment and dementia: a bivariate meta-analysis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 36, 239–251 (2021).

Berry, R. B. et al. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. Version 2.6. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2020).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Abadi, M. et al. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4724125, https://www.usenix.org/conference/osdi16/technical-sessions/presentation/abadi (2015).

Acknowledgements

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. This study was supported by Internal Funds of KU Leuven (Bijzonder Onderzoeksfonds (BOF) KU Leuven) [C24/18/097], the Flemish Government (Flanders AI Research Program), and the Research Foundation Flanders [1SC2921N].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D.V., W.V.P., D.T., and B.B. designed the study concept. A.D. and P.B. acquired the data. A.D., D.T., B.B., and P.B. analyzed the data. E.H. developed the model under supervision of M.D.V. E.H. and A.D. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript for intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of University Hospitals Leuven. Informed consent was obtained from all participants or their caregiver. The clinical trial numbers were NCT04755504 (S64190/B3222020000148), NCT03617497 (S61745) respectively.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heremans, E.R.M., Devulder, A., Borzée, P. et al. Wearable sleep recording augmented by artificial intelligence for Alzheimer’s disease screening. npj Aging 11, 34 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00219-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00219-y