Abstract

Spine age estimated from lateral spine radiographs and DXA VFAs could be associated with fracture and mortality risk. In the VERTE-X cohort (n = 10,341, derivation set) and KURE cohort (n = 3517; external test set), spine age discriminated prevalent vertebral fractures and osteoporosis better than chronological age. Predicted age difference was associated with overall (adjusted HR [aHR] 1.22 per 1 SD increment, p < 0.001), vertebral, non-vertebral incident fractures, and mortality (aHR 1.31, p = 0.001) during a median 6.6 years follow-up in KURE, independent of chronological age and covariates. Spine age to estimate FRAX hip fracture probabilities, instead of chronological age, improved the discriminatory performance for incident hip fracture (AUROC 0.83 vs. 0.78, p = 0.027). Shorter height, lower femoral neck BMD, diabetes, vertebral fractures, and surgical prosthesis were associated with higher predicted age difference, explaining 40% of variance. Spine age estimated from lateral spine radiographs and DXA VFA enhanced fracture risk assessment and mortality prediction over chronological age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fractures are a major health burden related to aging, posing significant morbidity and mortality globally1. According to the Global Burden of Disease study, the absolute incidence, years lived with disability, and health care costs for fracture increased substantially between 1990 and 2019, with the highest incidence in the oldest old age group1. Although several fracture risk assessment tools are available, there is room to improve the performance of individualized assessment to facilitate the optimal use of pharmacologic interventions for fracture prevention2.

Biological age represents the state of the body or organ system of an individual estimated as an integrated value of biophysiological measures in contrast to the chronological age as the time since the individual’s birth3. Biological age, estimated from various imaging modalities including brain magnetic resonance images (MRI)4, eye retinal photographs5, and chest radiographs6, outperformed chronological age in predicting health outcomes, including mortality. However, attempts to estimate biological age in the musculoskeletal system using imaging data are limited.

In this context, we propose a novel concept of ‘spine age’, an imaging-derived surrogate marker that reflects the biological aging of the spine based on structural features observed in lateral spine radiographs. Unlike chronological age, a fundamental input in most existing risk prediction tools, spine age may more precisely capture individual variation in musculoskeletal aging. Incorporating spine age in place of, or in addition to, chronological age in widely used prediction models could enhance fracture risk stratification, enabling more accurate identification of individuals who are likely to benefit from intervention.

In this study, we developed a convolutional neural network model to estimate spine age from lateral spine radiographs and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) vertebral fracture assessment (VFA) images. Discriminatory performance for prevalent vertebral fracture and osteoporosis was compared for biological spine age versus chronological age. The prognostic value of predicted spine age difference for incident fracture and mortality was assessed with adjustment for chronological age, sex, and covariates.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Median follow-up duration was 5.4 years (interquartile range [IQR] 2.6–7.7 years) in the derivation test set (VERTE-X) and 6.6 years (IQR 5.5–7.5 years) in the external test set (KURE). Incidence rates of overall fracture events during follow-up were 20.5/1000 person-years and 21.0/1000 person-years in the derivation test set (251/2063, 12.2%) and external test set (473/3508, 13.5%), respectively. Participants with versus without incident fracture during follow-up had older chronological and predicted spine age, with a higher prevalence of women, previous history of fracture, morphometric vertebral fracture, surgical prosthesis in the spine, and lower DXA areal BMD (Table 1).

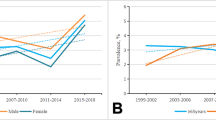

Discriminatory ability of chronological age and predicted spine age

The Pearson correlation coefficient between chronological age and spine age was 0.88 and 0.50 in the derivation test set and external test set (both p < 0.001), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3). Average predicted age difference (spine age minus chronological age) was −0.8 years (standard deviation 4.9) in the derivation test set and −0.5 years (standard deviation 8.0) in the external test set. Spine age showed better discriminatory performance for the presence of morphologic vertebral fracture or osteoporosis in both the derivation test set (Fig. 1; AUROC: vertebral fracture, 0.77 vs. 0.72; osteoporosis, 0.66 vs. 0.52) and external test set (AUROC: vertebral fracture, 0.66 vs. 0.60; osteoporosis, 0.65 vs. 0.57, all p < 0.001).

The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) was compared for chronological age and predicted spine age in discriminating vertebral fracture (A, C) and osteoporosis (B, D) within the derivation and external test sets. Predicted spine age consistently showed higher discriminatory performance than chronological age.

Association of predicted age differences with incident fracture

In Fig. 2, compared to the referent group of individuals of younger chronological age (below median; 65 years in the derivation test set and 72 years in the external test set) without accelerated spine age, younger chronological age with accelerated spine age was associated with a 2.21- and 1.60-fold elevated fracture risk in the derivation and external test sets, respectively. Participants of older chronological age (above the median) with accelerated spine age had the highest fracture risk in both cohorts (unadjusted hazard ratio [HR] 6.67 and 2.53 in derivation and external test sets, respectively). In the derivation and external test sets, each standard deviation increment of predicted age difference was associated with greater risk of overall (adjusted HR [aHR] 1.71 and 1.22, respectively), vertebral (aHR 1.55 and 1.34), and non-vertebral fractures (aHR 1.89 and 1.15, all p < 0.05), independent of age, sex, prevalent morphologic vertebral fracture, clinical risk factors, and osteoporosis (Table 2).

Kaplan–Meier cumulative failure curve for overall incident clinical fracture in the A spine radiograph cohort (derivation test set) and B DXA VFA cohort (external test set) from combinations of chronological age (< or ≥ median) and predicted spine age (accelerated spine age versus non-accelerated age). Accelerated spine age was defined using the highest tertile threshold of predicted age difference (predicted spine age minus chronological age ≥+1) in the derivation test set. HR unadjusted hazard ratio.

Reclassification of FRAX risk categories by predicted spine age

When FRAX probabilities for major osteoporotic fracture and hip fracture were calculated using predicted spine age in the place of chronological age in the derivation test set, up-classification from low to high risk group was observed in 53 individuals (53/2063, 2.5%), whereas 144 were down-classified from high to low risk (144/2063, 6.9%; Supplementary Fig. 4). Individuals who remained at high risk had the highest fracture risk (28.9%), followed by the low to high up-classified group (24.5%). High risk by FRAX probabilities based on estimated spine age versus FRAX probabilities from chronological age demonstrated higher positive predictive value (28.3% vs. 25.2%, respectively) but lower sensitivity (40.6% vs. 45.4%), yielding modest improvement in odds ratios (4.1 vs. 3.6) for incident fracture (Supplementary Table 2). Using image-predicted spine age instead of chronological age improved the discriminatory performance of FRAX probabilities to predict hip fracture (FRAX MOF probabilities: AUROC 0.81 vs. 0.77, p = 0.007; FRAX hip fracture probabilities: 0.83 vs. 0.78, p = 0.027; Supplementary Table 3) and FRAX hip fracture probabilities to predict overall fractures (AUROC 0.74 vs. 0.72, p = 0.024), although the difference in discriminatory performance for overall incident fracture between FRAX MOF probabilities based on spine age and chronological age to did not reach statistical significance (AUROC 0.74 vs. 0.73, p = 0.097).

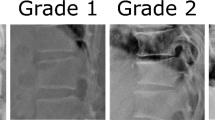

Factors associated with predicted age difference

In Supplementary Fig. 5, examples of GRAD-CAM (visualizing the pixels with the largest influence on the CNN model’s spine age prediction) for spine radiographs from individuals with and without accelerated spine age are presented. Images with accelerated spine age showed the presence of morphologic vertebral fracture (Supplementary Fig. 5A), vertebroplasty or surgical prosthesis (Supplementary Fig. 5B), and aortic calcification with various degrees of degenerative changes (Supplementary Fig. 5C). Male sex (+0.66 year vs. women), lower height (+0.31 year per 5 cm decrement), presence of diabetes mellitus (+0.51 year), prevalent morphometric vertebral fracture (+1.64 year), lower femoral neck BMD (+0.64 year per 1 standard deviation decrement), and presence of surgical prosthesis (+1.15 year) were associated with higher predicted age difference in a multivariable linear regression model, with about 40% of variance in predicted age difference explained by the model (adjusted R2 0.40; Supplementary Table 4).

Spine age and mortality

In the external test set of community-dwelling older adults, individuals with accelerated spine age had elevated risk of mortality compared to those without (unadjusted HR 1.36, p = 0.036; Supplementary Fig. 6). Higher predicted age difference was associated with greater risk of mortality, independent of chronological age, sex, prevalent morphologic vertebral, fracture, and clinical biomarkers related to mortality including serum albumin, hemoglobin, and creatinine (Table 3; adjusted HR 1.31 per 1 standard deviation increment in predicted age difference, 95% CI 1.12–1.53, p = 0.001).

Discussion

In this study, spine age estimated from lateral spine radiographs and DXA VFA images using a convolutional neural network outperformed chronological age for discriminating presence of morphologic vertebral fracture or osteoporosis in older adults. About 40% of the variance in predicted age difference, calculated as spine age minus chronological age, was explained by chronological age, sex, height, femoral neck BMD, presence of diabetes mellitus, morphologic vertebral fracture, and surgical prosthesis in the spine images. Higher predicted age difference was associated with greater risk of fracture and mortality independent of prevalent vertebral fracture, osteoporosis, and other covariates. Utilizing predicted spine age instead of chronological age to calculate FRAX probabilities yielded modest improvements in the discriminatory performance for incident fracture events.

Several studies have shown the potential of artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques to enhance fracture risk assessment, mostly by improving detection of prevalent vertebral fracture or osteoporosis in plain radiographs or computed tomography images7,8,9. In a study of longitudinal DXA whole body images to predict mortality, features derived from the raw whole body DXA images using deep learning predicted all-cause mortality with and without clinical risk factors10. Recurrent neural network models using sequential whole-body DXA scans outperformed the comparable model using only one observation. This study indicated that deep learning models could be trained to capture information on what constitutes healthy aging from simple two-dimensional musculoskeletal images, beyond the detection of known risk factors such as prevalent fracture or osteoporosis. In line with this notion, we confirmed the feasibility of estimating biological spine age from simple imaging sources such as lateral spine radiographs or DXA VFA by training a deep learning model. Predicted age difference was associated not only with incident fracture outcomes but also with mortality, indicating the potential utility of estimated spine age as an image-derived biomarker for aging-related outcomes beyond fracture risk assessment.

Factors contributing to the difference between estimated spine age and chronological age were identified from a multivariable linear regression model. We observed an association of male sex with accelerated spine aging, along with known risk factors such as lower height11, lower femoral neck BMD12, presence of diabetes mellitus13, morphologic vertebral fracture14, and surgical prosthesis15 in spine images. A study of opposite-sex twins reported that men were biologically older than women and the association of sex with accelerated aging was stronger in older twins using epigenetic clocks, which supports the sex disparity observed in spine age16. Despite the inclusion of well-established risk factors for fracture, the model only explained 40% of the variance in predicted age difference, indicating that some information in the spine images was not considered in the explainability model but contributed substantially to spine age estimation. As highlighted in GRAD-CAM images, the presence of aortic calcification could be associated with accelerated spine aging17. Degenerative change in the spine could also contribute to the estimated spine age18. The association of predicted spine age difference with incident fracture and mortality might be partly mediated by central obesity and low lean mass, which affect soft tissue in spine radiographs, though this needs to be explored in future studies. Taken together, these findings portend that biological age estimated from lateral spine radiographs and DXA VFA images have potential to serve as an integrated biomarker of aging and age-related health outcomes.

Although spine age showed a meaningful association with both vertebral fracture and osteoporosis, the discriminatory performance for prevalent osteoporosis was modest. This likely reflects the multifactorial nature of spine aging. While osteoporosis is a major contributor to vertebral fragility, spine age captures a wider array of structural changes, including vertebral deformities and age-related degeneration in bone and soft tissues, that are not fully explained by low BMD. Thus, the limited discriminative power for osteoporosis may underscore the broader biological construct that spine age represents beyond BMD, which in turn offers the potential to enhance fracture risk assessment when used in combination with conventional metrics.

Estimation of biological age from clinical data sources, including images, may provide new opportunities to improve clinical practice. Our approach demonstrates a meaningful improvement in discriminatory performance for incident fracture, especially at the hip, when spine age is incorporated into the FRAX probability estimation instead of chronological age. The discriminatory performance of FRAX probabilities without BMD for incident hip fracture has been reported AUROCs ranging from 0.74 to 0.7919,20,21. In our study, FRAX hip fracture probability without BMD alone achieved an AUROC of 0.78, which increased to 0.83 when spine age was incorporated. This represents a notable improvement in discriminatory ability, suggesting that spine age derived from images captures additional aging features relevant to fracture risk. This finding provides a proof-of-concept example for enhanced fracture risk assessment from inductive, bottom-up deep learning, such as estimated spine age, as a complement to well-established statistical modeling based on hypothesis-driven, top-down domain-specific knowledge8.

This study has several limitations. Derivation and test datasets are limited to Korean ethnicities; whether this finding would be applicable to individuals of other ethnicities needs to be examined further. Individuals with ages younger than 40 years were not included in the training dataset. FRAX probabilities were calculated without BMD because BMD data were limited to a subset of study participants in the derivation set. Antero-posterior view spine radiographs were not utilized to calculate spine age; whether utilizing both lateral and antero-posterior view spine images could improve the prediction of spine age merits further investigation. Frailty, muscle mass, and physical performance measurements were not available in this study; whether spine age is associated with frailty needs to be studied. Although estimated spine age from VFA images using a model trained in lateral spine radiographs showed similar predictive performance for incident fracture outcome, the correlation of spine age with chronological age was weaker in the VFA cohort. This is partly due to a domain shift or reflecting the true pattern in older individuals. VFA images from different manufacturers, such as GE, have different characteristics from VFA images from Hologic and lateral spine radiographs, requiring additional validation. Clinical application of spine age requires further verification. Future studies incorporating multi-omics data and epigenetic clocks may provide deeper insights into the biological underpinnings of spine age.

To summarize, spine age estimated from lateral spine radiographs and DXA VFA predicted incident fracture and mortality in adults independent of age, sex, prevalent vertebral fracture, osteoporosis, and other covariates. Spine age outperformed chronological age in discriminating prevalent vertebral fractures and osteoporosis. The discriminatory performance of FRAX probabilities for incident fracture outcome improved modestly when spine age was used as an input variable instead of chronological age.

Methods

Study participants

Derivation cohort: Demographic and clinical data of individuals who underwent lateral spine radiographs at Severance Hospital, Seoul, Korea, between January 2007 and December 2018 were collected (Supplementary Fig. 1; the VERTEbral fracture and osteoporosis detection in spine X-ray study, VERTE-X)7,22. The requirement for written permission for the medical record review was waived by the Institutional Review Board (IRB no. 4-2021-0937). Cohort entry date (index date) was the date of initial spine radiograph acquisition. We excluded individuals with an age younger than 40 years, a history of bone metastasis or hematologic malignancy within 1 year prior to index date, severe scoliosis, kyphosis, poor image quality, non-Korean ethnicity, and those without follow-up radiographs at least 28 days after the index date. A total of 10,341 participants remained in the final cohort. The dataset was randomly split into train (60%), validation (20%), and a hold-out test set (20%).

External test cohort: Korean Urban Rural Elderly (KURE) cohort is a prospective cohort study of aging and health outcomes in community-dwelling older adults23. Details on the cohort have previously been published23,24. A total of 3517 individuals aged 65 years or older participated in the study at baseline (year 2012–2015) after obtaining written permission (IRB no 4-2012-0172). After excluding individuals without DXA VFA images (n = 9), a total of 3,508 participants remained in the external test cohort.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Image specifications and preprocessing

Lumbar spine radiographs and DXA VFA images were obtained using standardized acquisition protocols within a single institution (Supplementary Table 1). To standardize image inputs, histogram equalization and Min-Max normalization were applied to adjust intensity distributions. Approximately 5% of non-informative margins were cropped, and images were resized to 1024 × 512 pixels, maintaining aspect ratios. Images smaller than the target size were zero-padded and centrally aligned. VFA images, focused on the thoracolumbar spine with consistent framing, did not require cropping.

Spine age estimation

Model architecture for the convolutional neural network (CNN) to estimate spine age is presented in Supplementary Fig. 2. Using the EfficientNet-B4 architecture, we applied the mean-variance loss function proposed by Pan and colleagues25. This approach simultaneously penalizes the difference between the mean of the predicted spine age distribution and the chronological age (mean loss) and reduces the variance of the estimated distribution to maintain a concentrated prediction (variance loss). The model was trained using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1e−4. The batch size was set to 45, and the training ran for up to 100 epochs on four NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPUs. Although lateral spine radiographs and VFA images differ in their resolution, they share similar positioning and morphological features. Thus, we were able to extract features and predict spine age using a single CNN model for both modalities. To reduce modality-specific differences in the external test set, an age-level bias correction was applied to the external VFA test set based on Beheshti’s method26,27. This approach involves fitting the slope (α) and intercept (β) of a linear regression model between the predicted age difference (Predicted age minus chronological age) and chronological age in the training set through a 10-fold cross-validation. The resulting regression parameters are used to adjust the predicted values in the external test set. To enhance model explainability, we visualized regions of high importance in spine age prediction using gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM), which highlighted specific regions with strong weights from the CNN kernel28.

Outcomes

In the derivation set (lateral spine radiographs, VERTE-X), incident fracture was defined as any new-onset morphologic vertebral fracture confirmed on follow-up lateral spine radiographs or clinical non-vertebral fractures at the hip, distal forearm, upper arm, pelvis, and lower leg ascertained during follow-up from the Severance Hospital electronic medical records system until the last observation date (December 31, 2023). In the external test cohort (DXA VFA, KURE) of community-dwelling older adults, outcomes including clinical fracture (any clinical vertebra, hip, distal forearm, or proximal humerus fracture) and mortality were collected by interviewer-assisted questionnaire performed at the time of 4-year interval follow-up visit to the center or follow-up phone calls until December 31st, 2021, with subsequent outcome ascertainment using individual-level diagnosis codes and/or procedural codes obtained by linkage to the Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA; research data [M20190729878]) which covers 99% of residents in South Korea29.

Covariates

Information on chronological age, sex, height, weight, previous history of clinical fracture, chronic glucocorticoid use, and presence of rheumatoid arthritis at the time of cohort entry (index date) were collected by reviewing electronic health record of Severance Hospital in the derivation set (VERTE-X). In the external test set (KURE), information on covariates was collected at the time of cohort entry using interviewer-assisted questionnaires and anthropometry measurements. FRAX probability (Korean tool) for major osteoporotic fracture and hip fracture without BMD was calculated using an online calculator (https://frax.shef.ac.uk/frax/tool.aspx?country=25; web version 1.4.7). Unavailable covariates to calculate FRAX were entered as ‘no’ responses. High risk FRAX probabilities were defined as FRAX major osteoporotic fracture probability ≥20% or FRAX hip fracture probability ≥3%30. DXA areal bone mineral density (BMD) measurement (Discovery W and A, Hologic, USA) was available in 70% (1448/2063) of the derivation test set (VERTE-X) and 100% (3508/3508) of the external test set (KURE). Presence of osteoporosis was defined as DXA areal BMD T-score −2.5 or below (reference population: NHANES III young White female) from the lumbar spine, femoral neck, or total hip31.

Statistical analysis

Differences in clinical characteristics of study participants with or without incident fracture outcomes were compared using two-sample independent t-tests for continuous variables (presented as mean ± standard deviation) and chi-square test for categorical variables (presented as number and percentage). Discriminatory ability for the presence of morphologic vertebral fracture and osteoporosis at baseline was compared between chronological age and predicted spine age using the area under the receiver-operating characteristics (AUROC) by the De Long method32. Kaplan–Meier failure curves were plotted for incident fracture grouped by chronological age and predicted age difference (predicted spine age minus chronological age) among participants categorized as four groups based upon chronological age (above or below median) and presence of accelerated spine age (defined as highest tertile of predicted age difference [spine age minus chronological age] in the derivation test set, +1 year or higher). Proportional Cox hazard models were built to assess the association between predicted age difference (per one standard deviation increment) and incident fracture, with adjustments for age, sex, presence of prevalent vertebral fracture, clinical risk factors, and osteoporosis. A two-sided p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Data availability

Data sharing requests will be considered for research purposes upon a written request to the corresponding author. If agreed, deidentified participant data and/or deep learning model weights will be made available, subject to a data sharing agreement.

Code availability

All source codes to train a deep learning model to estimate spine age are publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/nkhong84/VERTE-X-Aging).

References

GBD2019. Global, regional, and national burden of bone fractures in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2, e580–e592 (2021).

Nguyen, T. V. Individualized fracture risk assessment: state-of-the-art and room for improvement. Osteoporos. Sarcopenia 4, 2–10 (2018).

Zhang, Q. An interpretable biological age. Lancet Healthy Longev. 4, e662–e663 (2023).

Wood, D. A. et al. Accurate brain-age models for routine clinical MRI examinations. NeuroImage 249, 118871 (2022).

Nusinovici, S. et al. Application of a deep-learning marker for morbidity and mortality prediction derived from retinal photographs: a cohort development and validation study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 5, 100593 (2024).

Raghu, V. K., Weiss, J., Hoffmann, U., Aerts, H. & Lu, M. T. Deep learning to estimate biological age from chest radiographs. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 14, 2226–2236 (2021).

Hong, N. et al. Deep-learning-based detection of vertebral fracture and osteoporosis using lateral spine X-ray radiography. J. Bone Miner. Res. 38, 887–895 (2023).

Hong, N., Whittier, D. E., Glüer, C.-C. & Leslie, W. D. The potential role for artificial intelligence in fracture risk prediction. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 12, 596–600 (2024).

Smets, J., Shevroja, E., Hügle, T., Leslie, W. D. & Hans, D. Machine learning solutions for osteoporosis—a review. J. Bone Miner. Res. 36, 833–851 (2021).

Glaser, Y. et al. Deep learning predicts all-cause mortality from longitudinal total-body DXA imaging. Commun. Med. 2, 102 (2022).

Lee, C., Park, H. S., Rhee, Y. & Hong, N. Age-dependent association of height loss with incident fracture risk in postmenopausal Korean women. Endocrinol. Metab. 38, 669–678 (2023).

Cummings, S. R. et al. Bone density at various sites for prediction of hip fractures. Lancet 341, 72–75 (1993).

Zoulakis, M., Johansson, L., Litsne, H., Axelsson, K. & Lorentzon, M. Type 2 diabetes and fracture risk in older women. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2425106 (2024).

Lentle, B. C. et al. Comparative analysis of the radiology of osteoporotic vertebral fractures in women and men: cross-sectional and longitudinal observations from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos). J. Bone Miner. Res. 33, 569–579 (2018).

Nakahashi, M. et al. Vertebral fracture in elderly female patients after posterior fusion with pedicle screw fixation for degenerative lumbar pathology: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 20, 259 (2019).

Kankaanpää, A. et al. Do epigenetic clocks provide explanations for sex differences in life span? A cross-sectional twin study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 77, 1898–1906 (2022).

Gebre, A. K. et al. Abdominal aortic calcification, bone mineral density, and fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 78, 1147–1154 (2023).

Ye, C. et al. Association of vertebral fractures with worsening degenerative changes of the spine: a longitudinal study. J. Bone Min. Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/jbmr/zjae172 (2024).

Ettinger, B. et al. Performance of FRAX in a cohort of community-dwelling, ambulatory older men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) study. Osteoporos. Int.24, 1185–1193 (2013).

Crandall, C. J. et al. Do additional clinical risk factors improve the performance of fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX) among postmenopausal women? Findings from the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study and Clinical Trials. JBMR Plus3, e10239 (2019).

Leslie, W. D. et al. Does osteoporosis therapy invalidate FRAX for fracture prediction?. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 1243–1251 (2012).

Hong, N. et al. Deep learning-based identification of vertebral fracture and osteoporosis in lateral spine radiographs and DXA vertebral fracture assessment to predict incident fracture. J. Bone Miner. Res. 40, 628–638 (2025).

Hong, N. et al. Cohort profile: Korean Urban Rural Elderly (KURE) study, a prospective cohort on ageing and health in Korea. BMJ Open 9, e031018 (2019).

Lee, E. Y. et al. The Korean urban rural elderly cohort study: study design and protocol. BMC Geriatr. 14, 33 (2014).

Pan, H., Han, H., Shan, S. & Chen, X. Mean-Variance Loss for Deep Age Estimation from a Face, 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018, pp. 5285-5294, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2018.00554.

Zhang, B., Zhang, S., Feng, J. & Zhang, S. Age-level bias correction in brain age prediction. NeuroImage Clin. 37, 103319 (2023).

Beheshti, I., Nugent, S., Potvin, O. & Duchesne, S. Bias-adjustment in neuroimaging-based brain age frameworks: a robust scheme. NeuroImage Clin. 24, 102063 (2019).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization, 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 2017, pp. 618-626, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2017.74.

Kim, J. A., Yoon, S., Kim, L. Y. & Kim, D. S. Towards actualizing the value potential of Korea Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) data as a resource for health research: strengths, limitations, applications, and strategies for optimal use of HIRA data. J. Korean Med. Sci. 32, 718–728 (2017).

Cosman, F. et al. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 25, 2359–2381 (2014).

Looker, A. C. et al. Prevalence of low femoral bone density in older U.S. adults from NHANES III. J. Bone Min. Res. 12, 1761–1768 (1997).

DeLong, E. R., DeLong, D. M. & Clarke-Pearson, D. L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44, 837–845 (1988).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (2013-E63007-01, 2013-E63007-02, 2016-ER6302-00; 2016-ER6302-01; 2016-ER6302-02; 2019-ER6302-00; 2019-ER6302-01), a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI22C0452) to NH, and a grant of International Cooperation (R&D) (Joint Research) with Switzerland through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea (RS-2023-00231864) to N.H. The funding sources had no involvement in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, and decision to submit the paper. We appreciate the effort of the participants and investigators of the KURE cohort study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sang Wouk Cho: software, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, visualization, writing—review and editing; Namki Hong: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, visualization, writing—review and editing; Kyoung Min Kim: conceptualization, project administration, funding acquisition, investigation, resources, methodology, writing—review and editing; Young Han Lee: writing—review and editing, visualization, methodology; Chang Oh Kim: writing—review and editing, resources, data curation; Hyeon Chang Kim: writing—review and editing, resources, data curation; Yumie Rhee: writing—review and editing, supervision, resources, data curation; Brian H. Chen: methodology, data curation, writing—review and editing; William D. Leslie: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing; Steven R. Cummings: conceptualization, supervision, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, S.W., Hong, N., Kim, K.M. et al. Spine age estimation using deep learning in lateral spine radiographs and DXA VFA to predict incident fracture and mortality. npj Aging 11, 83 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00271-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00271-8