Abstract

Tourism in Paleolithic caves can cause an imbalance in cave microbiota and lead to cave wall alterations, such as dark zones. However, the mechanisms driving dark zone formation remain unclear. Using shotgun metagenomics in Lascaux Cave’s Apse and Passage across two years, we tested metabarcoding-derived functional hypotheses regarding microbial diversity and metabolic potential in dark zones vs unmarked surfaces nearby. Taxonomic and functional metagenomic profiles were consistent across years but divergent between cave locations. Aromatic compound degradation genes were prevalent inside and outside dark zones, as expected from past biocide usage. Dark zones exhibited enhanced pigment biosynthesis potential (melanin and carotenoids) and melanin was evidenced chemically, while unmarked surfaces showed genes for antimicrobials production, suggesting that antibiosis might restrict the development of pigmented microorganisms and dark zone extension. Thus, this work revealed key functional microbial traits associated with dark zone formation, which helps understand cave alteration processes under severe anthropization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Show caves are among the most important geotouristic sites world-wide, with more than 250 million people visiting them each year1,2,3. Show caves attract tourist attention for underground lakes e.g. in Cross Cave (Slovenia), speleothems such as stalactites and stalagmites e.g. in Kartchner Cave (Arizona, USA) and Aven d’Orgnac (France), or parietal artwork e.g. in Lascaux Cave (France) and Altamira Cave (Spain)4,5,6,7. However, caves are extremely fragile environments and can be affected by intense touristic activity, because of development work including cave floor excavation to facilitate access8, installation of stairs, elevators, lighting system, masonry9 and sometimes digging of a tunnel10, as well as human frequentation that brings in microorganisms and changes climatic conditions7. This can be problematic for conservation of Paleolithic artwork, as it can cause alterations on the walls (biodeterioration, lampenflora, calcite veil, gypsum efflorescences, dark ferromanganese deposits, microbial stains, etc.) in various subterranean environments5,11,12,13,14,15,16. In several caves, antibiotic and chemical treatments were applied to cave floors and walls in an attempt to mitigate microbial alterations, which sometimes exacerbated further the imbalance of the cave microbiota9,12.

These conservation problems are well illustrated in Lascaux Cave, where tourism-related anthropization resulted in various cave wall alterations and led to cave closure in 196312. The alterations on walls corresponded to an abnormal proliferation of the algae Brateococcus minor in the 1960s (green biofilms) and later of microorganisms such as the fungi Fusarium solani in 2001 (white stains), Ochroconis lascauxensis (syn. Scolecobasidium lascauxense) and other black melanized fungi since late 2001 (black stains)17,18,19. These proliferations were treated with chemical and antibiotic compounds applied directly on walls, such as formaldehyde, quicklime, streptomycin, polymixin and benzalkonium chloride (BAC). The last type of rock wall alteration corresponds to dark zones, which started in the Apse in 2008 and developed in different rooms in recent years18. They are zones of darker shade than on unmarked surfaces around, but without the black color of black stains documented in relation to black melanized fungi. Their chemical basis is not known, and perhaps they entail synthesis of pigments and/or chemical modifications of metals, as documented for other alterations6,19. Preliminary microbial analysis evidenced a particular microbial community in dark zones, with the counter-selection of the Gammaproteobacteria class18, as well as the selection of pigmented fungi (e.g. Ochroconis) and the Alphaproteobacteria class including the genus Bosea described as producer of carotenoids (yellow-orange pigments corresponding to isoprenoid polyenes) and other pigments20.

Previous work on dark zones was carried out using metabarcoding18, which (i) might entail a PCR bias when considering microbial diversity and (ii) does not enable reliable prediction of microbial functions involved in these surface alterations. Thus, the objective of this work was to use high-throughput metagenomic sequencing (i.e. NovaSeq) to compare the microbial ecology of dark zones vs unmarked surfaces nearby (Fig. 1), in terms of microbial diversity and metabolic potential relevant to understand dark zone formation in Lascaux Cave.

A Photograph of unmarked surfaces (UN) and dark zones (DZ) in the Apse (2020 and 2021) and Passage (2021) (Source: S. Géraud, DRAC Nouvelle Aquitaine). B Map of Lascaux Cave presenting the locations studied. The natural limestone is indicated in red and artificial limestone in green (Source of the map: S. Konik, Centre National de la Préhistoire).

In dark zones of the Apse, pigmented fungi such as Ochroconis lascauxensis become selected, whereas Pseudomonas bacteria are counter-selected as indicated by metabarcoding18, and here we hypothesized that they would be confirmed with a PCR-free metagenomic approach. A second hypothesis is that these differences in taxonomic diversity would translate into key differences in metabolic potential. More specifically, two issues were targeted. One issue is the past application of chemical treatments such as BAC, as some bacteria and fungi from polluted soil or caves present the ability to degrade BAC into benzyldimetylamine, benzylamine and benzoic acid usable by fungi for their growth and metabolism e.g. pigment biosynthesis21,22, and it can be expected that microbial communities would be enriched in (i) aromatic compound degradation pathways, in and outside dark zones, and (ii) pathways involved in biosynthesis of pigments e.g. carotenoids or in chemical modifications of metals, specifically in dark zones. The other issue is the patchy distribution of dark zones, which raises the possibility that pigmented fungi may be controlled by antimicrobials produced by other microorganisms present on unmarked surfaces23, thereby limiting the expansion of dark zones. For example, bacterial genera such as Pseudomonas or Streptomyces, widely present in caves24,25, have the potential to secrete antimicrobial compounds, like the Pseudomonas metabolites 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol26, pyrrolnitrine27 or hydrogen cyanide28 and a wide range of Streptomyces antimicrobials29,30. Finally, in caves, metabarcoding data indicate that the diversity of the microbial community can differ significantly from one room to the other but fluctuations in time are typically minor, including in Lascaux31. Against this background, our third hypothesis was that metagenomic data may differ when comparing the two Lascaux locations studied, but without a significant effect of sampling time.

Results

Microbial community structure

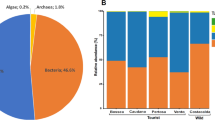

After assembly process, contigs were affiliated at 84.6% (±4.5%) to Bacteria, 1.8% (±0.8%) to Eukaryota, and 0.08% (± 0.04%) to Archaea using LCA, based on all genes/ORFs including ribosomal sequences (Supplementary table 1). NMDS analysis of the whole metagenomic dataset showed that microbial community structure statistically depended on the room (i.e., Apse or Passage ; 37% of the variation) and rock surface condition (i.e. dark zone or unmarked samples ; 18% of the variation), but much less on the sampling time (i.e., 2020 or 2021 ; 6% of the variation) (Table 1). NMDS ordination was confirmed by pairwise adonis tests for the effect of room (P = 0.004 for Passage vs Apse, P = 0.004 for Passage vs Apse 2020, and P = 0.005 for Passage vs Apse 2021) and surface condition (dark zone vs unmarked surface ; P = 0.007 with all samples, P = 0.001 in Apse 2020, P = 0.001 in Apse 2021 and P = 0.019 in Passage 2021), and the lack of effect of time (P = 0.081) (Fig. 2, Table 1). NMDS distinguished four groups of samples corresponding to (i) unmarked surfaces from the Apse (2020 and 2021), (ii) dark zones from the Apse (2020 and 2021), (iii) unmarked surfaces from the Passage (2021), and (iv) close to the latter the dark zones from the Passage (2021) (Fig. 2).

Microbial community composition

Microbial community composition was assessed after pooling Illumina NovaSeq ribosomal sequences from the three replicates (i.e. per room and rock surface condition), separately in 2020 and 2021. The 18 metagenome datasets consisted in 245,692 contigs (>2000 bp) on average, with 888,686 bp for the longest contig (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

The unmarked surfaces from both the Apse and the Passage displayed 11 microbial phyla. As expected from community structure data, the Apse (2020 and 2021) and Passage (2021) samples from unmarked surfaces presented contrasted microbial compositions (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 1). Indeed, some bacterial phyla were enriched in the Apse compared with the Passage, such as Acidobacteria (7.6% vs 0.9%) and Proteobacteria (65.4 vs 28.4%), whereas others were in lower proportion in the Apse, such as Bacteroidetes (0.1% vs 12.0%) and Actinobacteria (4.6% vs 49.5) (Fig. 3A). Not surprisingly, this type of finding held still true when considering lower taxonomic levels, such as class and genus (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). For instance, Gammaproteobacteria were more abundant in the Apse than in the Passage (45.1% vs 4.9%, Fig. 3B), which was mainly due to the Pseudomonas genus abundant in the Apse (42.1%) but rare in the Passage (<0.1%) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Conversely, the Apse displayed a lower proportion of Actinomycetia (4.0 vs 46.5%, Fig. 3B), among which the Jiangella genus reached <0.1% in the Apse but 9.1% in the Passage (Supplementary Fig. 3). In contrast, the Alphaproteobacteria class had a similar relative abundance in the Apse (16.6%) and the Passage (19.8%).

Dark zone alterations from the Apse and the Passage were characterized by the presence of 10 different phyla. They displayed similarities in community composition, e.g. the predominance of the Proteobacteria phylum (64.5% on average; Fig. 3A) and Alphaproteobacteria class (46.9% on average; Fig. 3B), but also a few differences. At the phylum level, dark zone samples presented a higher proportion of Acidobacteria (1.9% vs <0.1%), Bacteroidetes (11.9% vs 7.3%) and Actinobacteria (17.4% vs 4.5%) in the Apse compared with the Passage (Fig. 3A). At the class level, Gammaproteobacteria (16.3% vs 4.7%), Actinomycetia (16.2% vs 4.2%) and Chitinophaga (8.3% vs 4.2%) in dark zones were also more abundant in the Apse, whereas the Betaproteobacteria were less abundant (2.3% vs 5.6%, which paralleled the levels of the Achromobacter genus i.e. 0.3% vs 3.9%, respectively; Supplementary Fig. 2) (Fig. 3B).

When comparing dark zones and unmarked surfaces, the relative abundance of the Acidobacteria phylum was lower in dark zones (0.8% vs 7.6% in the Apse and 4.5% vs 49.5% in the Passage). Conversely, the Proteobacteria were at similar levels in and outside dark zones in the Apse (65.4% vs 62.1%), but in the Passage they represented 69.2% in dark zones vs only 28.5% in unmarked surfaces. In addition, the Bacteroidetes amounted to 9.6% in dark zones vs only 0.1% in unmarked surfaces of the Apse, but 7.3% in dark zones vs as much as 12.0% in unmarked surfaces of the Passage. At the class level, dark zones (in comparison with unmarked surfaces) displayed a higher relative abundance of Alphaproteobacteria (37.0% vs 16.6% in the Apse and 56.8% vs 20.2% in the Passage), Deltaproteobacteria in the Apse (3.1% vs <0.1%) but not the Passage (0.5% vs 1.1%), and Actinomycetia in the Apse (16.2% vs 4.1%) but not the Passage (4.2% vs 46.6%). Conversely, the Betaproteobacteria were at similar levels in and outside dark zones in the Apse (2.3% vs 2.8%), but in the Passage they reached 5.6% in dark zones vs only 0.9% in unmarked surfaces. In addition, dark zones (in comparison with unmarked surfaces) exhibited a lower relative abundance of Gammaproteobacteria in the Apse (16.3% vs 45.1%) but not in the Passage (4.9% vs 4.7%). At the genus level, Achromobacter and Mesorhizobium were at lower levels in dark zones than on unmarked surfaces in the Apse (0.3% vs 2.4% and 1.9% vs 2.7%, respectively) and the Passage (3.2% vs 14.2% and 0.1% vs 6.4%, respectively), and so was Pseudomonas in the Apse (<0.1% vs 42.0%) but not in the Passage (3.8% vs 3.2%). Conversely, Chitinophaga amounted to 8.8% of sequences in dark zones vs only <0.1% in unmarked surfaces, but levels were similar in the Passage (5.1% vs. 3.6%).

The first hypothesis was that microbial diversity indicated by metabarcoding would be confirmed with a PCR-free metagenomic approach. This hypothesis proved correct in the Apse for Bacteria, with noticeably a counter-selection of the Gammaproteobacteria (e.g. Pseudomonas) as well as the selection of Alphaproteobacteria class in dark zones, both for metabarcoding and metagenomic datasets, but not for microeukaryotes due to insufficient metagenomics coverage (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). For the Passage the hypothesis was not valid for Bacteria and microeukaryotes, in both surface conditions. For instance, the counter-selection of Gammaproteobacteria (including Pseudomonas) and selection of Chitinophagia (Bacteroidota) observed by metabarcoding was not confirmed by metagenomic approach.

Microbial genetic potential

The metagenomes (n = 18) from each rock surface condition were used to explore the genetic potential of communities thriving in Lascaux Cave. Based on contigs analysis, up to 1.95 × 106 genes with predicted functions were identified per sample (average: 9.04 × 105 genes). These genes were distributed into at least 13,824 different molecular-level functions according to KEGG orthology.

First, the focus was put on pathways for aromatic compound degradation, expected to be operational in and outside dark zones, and indeed genes brcD and brcC (benzoyl-CoA reductase subunits D and C), pcpD (tetrachlorobenzoquinone reductase), phtD (4,5-dihydroxyphthalate decarboxylase) and poxF (phenol hydroxylase P5) were found in and outside dark zones, in the Apse and the Passage, and at similar levels in and outside dark zones (respectively P = 0.07, P = 0.13, P = 0.32, P = 0.10, P = 0.10 in the Apse and P = 0.12, P = 0.30, P = 0.10, P = 0.15, P = 0.20 in the Passage) (Fig. 4). The genes for degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons padAb and padAd (phthalate 3,4-dioxygenase subunits beta and alpha) and phdK (2-formylbenzoate dehydrogenase), and toluene bbsA and bbsC (both benzoylsuccinyl-CoA thiolases) and poxF were evidenced in and outside dark zone, at similar levels in the Apse (respectively P = 0.42, P = 0.06, P = 0.21 for the former and P = 0.10, P = 0.23, P = 0.18 for the latter), at higher levels for bbsA (P = 0.02), bbsC (P = 0.02) and lower levels for padAb (P = 0.04), padAd (P = 6.3 × 10−5), phdK (P = 0.01), poxF (P = 7.8 × 10−5) in dark zones in the Passage. In addition, dark zones (in comparison with unmarked surfaces) exhibited a lower relative number of genes badH (2-hydroxycyclohexanecarboxyl-CoA dehydrogenase) for benzoate degradation (P = 1.2 × 10−4) and bbsF (benzylsuccinate CoA-transferase) for toluene degradation (P = 1.3 × 10−4) in the Apse, but not in the Passage (P = 0.19 and P = 0.08, respectively). Therefore, genes for aromatic compound degradation were found both in and outside dark zones, as expected, and often occurred at similar levels.

The relative abundance of selected genes is represented using a gradient (0 to 40,000 sequences), with purple shades indicating higher abundances. The sampling year is indicated with a pink vertical line for 2020 and a black vertical line for 2021. The significance of Wilcoxon tests for comparison of unmarked surfaces and dark zones is represented by colors placed between unmarked surfaces data and dark-zones data, using a gradient (P value of 1 to 0.0001), with green shades indicating significant P values. NA (Non-Applicable): relative abundance of selected genes was 0. Metabolic functions associated with selected genes are detailed in Supplementary Table 5.

Second, since the darker shade associated with dark zones might entail microbial pigment production (hypothesis), we assessed the possibility that biosynthetic genes for organic compounds (pigments) would be more prevalent in dark zones than on unmarked surfaces. Consistent with this hypothesis, dark zones (in comparison with unmarked surfaces) displayed a higher relative number of carotenoid biosynthesis genes crtA (spheroidene monooxygenase, P = 7.5 × 10−4), crtB (15-cis-phytoene synthase, P = 0.03), crtD (1-hydroxycarotenoid 3,4-desaturase, P = 9.4 × 10−5), crtQ (4,4’-diaponeurosporenoate glycosyltransferase, P = 1.1 × 10−4), crtX (zeaxanthin glucosyltransferase, P = 0.02), crtZ (beta-carotene hydroxylase, P = 2.4 × 10−4) and melanin (black pigments resulting from polymerization of phenolic and/or indolic compounds) biosynthesis genes dod (DOPA 4,5-dioxygenase, P = 0.04) and tyr (tyrosinase, P = 2.9 × 10−3) in the Apse, but not in the Passage (all P > 0.05) (Fig. 5). Another possibility for darker shades would be the contribution of metal biotransformations, and here genes related to manganese oxidation i.e., mox (manganese peroxidase) and mnp1 (manganese oxidase) were found, but at similar levels in and outside dark zones, both in the Apse (P = 0.20 for mox, P = 0.08 for mnp1) and the Passage (P = 0.29 for mox, P = 0.10 for mnp1) (Fig. 4). Thus, the hypothesis that dark zones are enriched in pigment biosynthesis genes proved correct in the Apse (i.e. for carotenoids and melanins) but not in the Passage, whereas the metal metabolism hypothesis was not substantiated.

The relative abundance of selected genes from A the Apse and B the Passage for unmarked surfaces and altered surfaces is represented using a gradient (0 to 40,000 sequences), with purple shades indicating higher abundances. The sampling year is indicated with a pink vertical line for 2020 and a black vertical line for 2021. The significance of Wilcoxon tests for comparison of unmarked surfaces and dark zones is represented by colors placed between unmarked-surface data and dark-zone data, using a gradient (P value of 1 to 0.0001), with green shades indicating significant P values. NA (Non-Applicable): relative abundance of selected genes was 0. Metabolic functions associated to selected genes are detailed in Supplementary Table 5.

Third, dark zones occur as patches on wall surfaces. It suggests that, on unmarked surfaces, pigmented fungi could be inhibited by other microorganisms present on these surfaces. To assess this possibility, genes coding for antimicrobials (especially antifungal metabolites) were sought, but only four biosynthetic genes were identified. These biosynthetic genes were at similar relative numbers in and outside dark zones for pyrrolnitrin (prnB) in the Apse (P = 0.13) and Passage (P = 0.07), and for hydrogen cyanide (hcnC ; P = 0.30 and P = 0.56, respectively) (Fig. 5). Conversely, the biosynthesis genes for hydrogen cyanide (hcnB) and pyocyanin (phzS) were in lower amounts in dark zones than in unmarked surfaces in the Apse (P = 0.02 and P = 2.1 × 10−4, respectively), but in similar amounts in the Passage (P = 0.21 and P = 0.23, respectively). Therefore, there was evidence for higher numbers of hydrogen cyanide and pyocyanin genes in unmarked surfaces but only in the Apse, but only few genes coding for antimicrobials were evidenced.

Fourth, the last hypothesis was that metagenomic data would differ according to Lascaux location. All genes involved in the types of metabolic functions above were found both in the Apse and Passage, but only 35% of them there were at similar relative abundances (P > 0.05) in unmarked surfaces from both locations. This is for instance the case for the melanin genes tyr (tyrosinase) and lac (laccase), and gene bbsB (acyltransferase) for degradation of polycyclic aromatics. On unmarked surfaces, the relative abundance of hydrogen cyanide gene hcnB (P = 0.03) was higher in the Apse compared with the Passage, and that of pyrrolnitrin genes prnA (P = 0.01) and prnB (P = 5.7 × 10−4), benzoate degradation genes e.g. thnJ (P = 6.5 × 10−4) and badH (P = 2.3 × 10−5), toluene degradation genes e.g. bbsF (P = 7.6 × 10−5), and genes for degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons e.g. padAd (P = 0.02) and phdK (P = 1.4 × 10−4) was lower (Fig. 3). In dark zones, more than 85% of the genes studied were at similar relative abundances (P > 0.05) in the Apse and Passage, e.g. genes hcnB, hcnC (hydrogen cyanide), prnA, prnB (pyrrolnitrin), phzS (pyocyanin), lac, tyr, dod (melanin), and tfdA (chloroalkane degradation). In dark zones, the relative abundance of carotenoid biosynthesis genes ccr2 (P = 4.2 × 10−4) and cruC (P = 2.4 × 10−4, Fig. 3) and toluene degradation genes poxC (P = 0.02), poxD (P = 0.03) and poxE (P = 0.03) was lower in the Apse compared with the Passage, and that of manganese metabolism gene mox (P = 0.03) and benzoyl-CoA reductase gene brcD (P = 0.04) was higher. Therefore, the hypothesis of a significant effect of the location within Lascaux proved correct.

Genomes assembled from community metagenomes

MAGs (Metagenome-Assembled Genomes) were reconstructed to scale up from individual genes to metabolic pathways and identify potential actors involved in metabolic pathways of interest. MAGs corresponding to representative microbial lineages present in Lascaux Cave were reconstructed, and metabolic capabilities were inferred from the MAGs presenting >75% completeness and contamination levels <5% (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 4).

The taxonomic column indicates the taxonomic level assigned for the MAGs with (d): domain, (p): phylum, (c): class, (o): order, (g): genus. Taxonomic affiliations are detailed in Supplementary Table 4. Identification of the pathways was carried out with MetaCyc and the KEGG pathway mapping tool. Green dots indicate biosynthesis pathways (aromatic compounds, secondary metabolites) and red dots degradation pathways (alcohols, aldehydes, aromatic compounds, and secondary metabolites).

First, we considered that genes for aromatic compound degradation were present in and out of dark zones, and here degradation pathways of benzoate, chlorobenzene and chlorophenol (and butanediol) were identified with MAGs reconstructed from both surface conditions, in the Apse (for Labrys) or in both rooms (for Xanthomonadaceae, Labrys, Luteimonas and Ralstonia) (Fig. 6). The metabolic pathways involved in the degradation of nitroaromatic compounds such as 2-nitrobenzoate and 2,4-dinitrotoluene were identified in MAGs reconstructed from Apse unmarked surfaces (Alphaproteobacteria and Streptomyces, respectively) but also in MAGs reconstructed from Passage dark zones (all proteobacterial MAGs, excepted Legionella). Metabolic pathways for degradation of aromatic compounds such anthranilate and catechol were identified only in MAGs reconstructed from unmarked surfaces in the Apse (Actinobacteria, Hyphomicrobiales and Rhodospirillales) and Passsage (Actinobacteria, Legionella, Streptomyces). Therefore, metabolic pathways associated with the degradation of aromatic compounds were found both in and out of the dark zones, as expected, but these pathways were overall present in greater numbers (2.4 vs 9.7 pathways on average, P = 0.004) in MAGs reconstructed from the unmarked surfaces.

Second, since microbial pigment production or metal biotransformations might be associated with darker shades on walls (i.e. dark zone), we assessed the occurrence of relevant metabolic pathways in MAGs. Metabolic pathways for biosynthesis of terpenoids, derived from carotenoids, such as the betaxanthin, geranyl-diphosphate and methylerythritol phosphate biosynthetic pathways were identified in MAGs originating from unmarked surfaces in the Apse (Actinobacteria, Hyphomicrobiales, Rhodospirillales, etc.) or both Apse and Passage (Actinobacteria and Legionella) (Fig. 6). Conversely, metabolic pathways associated with melanin biosynthesis, such as the L-dopachrome biosynthesis pathway, were identified in MAGs reconstructed from dark zone samples of the Apse only (Nitrobacter, Chitinophaga, Hypocreales) or of both rooms (Proteobacteria). Furthermore, no metabolic pathway involved in manganese metabolism was identified. Hence, the hypothesis that dark zones are enriched in pigment biosynthetic pathways was correct for melanin biosynthesis in both rooms, whereas the hypothesis of carotenoid and metal metabolism was not supported by MAG data.

Third, we considered metabolic pathways involved in the biosynthesis of antimicrobial compounds, in relation to the hypothesis that they might result into the inhibition of pigmented microorganisms on the unmarked surfaces. MAG analysis did not find pyrrolnitrin and HCN pathways despite the occurrence of individual biosynthetic genes (see above), but evidenced biosynthesis pathways for tetracycline in unmarked surfaces of the Apse (Streptomyces), vancomycins in both rock surface conditions of both rooms (Hyphomicrobiales, Microbacterium, Pedobacter, etc.), and rifamycins in dark zones of the Apse (Nitrobacter, Chitinophaga, etc.) and both surface conditions of the Passage (Hypomicrobiales, Sphingomonas, Streptomyces, etc.) (Fig. 6). Metabolic pathways for biosynthesis of siderophores (pyoverdine, petrobactin, enterobactin and bacillibactin) were identified in MAGs from unmarked surfaces, both for the Apse (Rhodospirillales, Bacteria) and the Passage (Pseudonocardiaceae, Bacteroidetes). Therefore, at the MAG level, there is evidence for an enrichment in unmarked surfaces of metabolic pathways involved in the biosynthesis of tetracycline and siderophores, but not for other antimicrobial compounds.

Fourth, the final hypothesis was that the metagenomic data would differ with Lascaux location. Indeed, the reconstructed MAGs were generally specific to their sampling location and only four MAGs originated from both rooms (for Bacteria, Proteobacteria, Xanthomonadaceae, and Ralstonia) (Fig. 6).

Discussion

For the two types of rock surface conditions and locations, a large proportion of Bacteria was identified (>84%), whereas microeukaryotes were poorly represented in all datasets (1.8%), including Fungi which accounted for 0.7% of sequences. This pattern was also observed using reconstructed genomes (MAGs), with only 1 out of the 53 MAGs affiliated with microeukaryotes (Fungi). Two explanations are possible. First, the low representation of microeukaryotes may be due to a limitation of bioinformatic methods for metagenomic analyses, which are not yet effective for eukaryotic sequences. Indeed, tools and databases devoted to metagenomic analyses are still highly biased toward prokaryote analyses32,33. Moreover, tools allowing the binning and quality estimation of MAGs are still limited, because (i) genome size is classically larger for eukaryotes than prokaryotes and (ii) eukaryotic marker genes present in large multiple copy numbers (between 14 and 1442 ITS copies for fungi compared with only 1-21 copies for bacterial 16S genes34) are often considered as indicators of contamination during the quality estimation of MAGs, distorting the result and leading to the non-selection of MAGs33,35, therefore reducing the relative amount of eukaryotic MAGs. This is a significant issue with metagenomics in all types of environments32,36. Second, it could also be that Bacteria outnumber the other types of microorganisms in caves37,38. This is suggested by quantitative PCR levels that were 1 or 2 log higher for 16S vs 18S rRNA genes in various Lascaux conditions31, but care is needed when drawing conclusions considering PCR bias. Archaea were also in minority compared with Bacteria, and even more so than what quantitative PCR had previously indicated39.

In this work, the priority was put on dark zones of the Apse, where the first identification of a dark zone was made (based on June 2008’ photographic archives). In the Apse, Acidobacteria and Proteobacteria (especially Gammaproteobacteria) predominated on unmarked surfaces, as previously reported in Lascaux Cave12,18,39 and other karstic caves25,40,41, based on cloning-sequencing and especially metabarcoding. Here, this was confirmed by metagenomic analysis of 16S rRNA markers (and in fact metabarcoding and metagenomics results for bacteria were convergent for all four conditions studied). Thus, we confirmed and expanded previous findings18,39 that dark zone formation on wall surfaces of the Apse coincides with major shifts in microbial community composition. This includes the counter-selection of Pseudomonas and the selection of various Alphaproteobacteria and the Bacteroidota genus Chitinophaga, a pioneer genus as soon as dark zone formation starts42. However, metagenomics did not prove effective to document community changes for microeukaryotes, as discussed above. For instance, we did not manage to detect any sequence affiliated with the black fungus Ochroconis, one of the most abundant taxa evidenced by 18S rRNA gene and ITS2 metabarcoding18,42. It points to the usefulness of using both metagenomics and metabarcoding to fully assess microbial diversity.

In the Apse, metagenomics brought new insight into the process of dark zone formation. First, it showed that genes and metabolic pathways for aromatic compound degradation and catechol formation were well present in microorganisms, both for dark zones and unmarked surfaces. BAC applied to the walls of Lascaux Cave displays a benzene ring43, and catabolism by several microorganisms including Pseudomonas44 may lead to the formation of catechol and fuel microbial growth. This highlights the need for alternative treatments, e.g. using mechanical tools45, to curb microbial outburst when occurring in caves.

Second, metagenomics evidenced in dark zones of the Apse an enrichment in pigment biosynthesis genes, both for carotenoids (Apse) and melanins (Apse and Passage). Significant functional differences between Apse and Passage can be expected, since dark zones form on native limestone surfaces in the Apse vs artificial calcareous benches in the Passage. It is of interest that catechol (see above) is a precursor of melanin in bacteria and fungi46,47,48. BAC degradation yields benzyldimethylamine, benzylamine and benzoic acid that might also be used for pigment biosynthesis21,22. In dark zones, some of the reconstructed MAGs affiliated with Proteobacteria, Nitrobacter (Alphaproteobacteria) and Chitinophaga (Bacteroidetes) presented L-dopachrome biosynthesis pathways, suggesting their ability to produce melanin. Indeed, L-dopachrome is involved in melanin biosynthesis47,49, by being spontaneously decomposed into 5,6-dihydroxyindole and CO250 or enzymatically converted into 5,6-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylate (L-dopachrome tautomerase)51. Dark zones are not black (unlike black stains), which suggests that melanins may not be produced in large amounts, yet preliminary chemical analyses of melanins based on the method of Ito et al.52. pointed to the occurrence of L-dopamelanin in the dark zone samples analyzed (and corresponding to samples collected from the Hall of Bulls, where larger quantities of material could be taken) but not in control samples nearby. Carotenoid analysis was attempted using absorbance at 464 nm, despite the lack of an established methodology for soil/rock samples, and it failed to evidence a significant signal in samples from the Passage (Apse samples could not be taken as walls there are too fragile). In addition, when pure β-carotene (in a chloroform solution) was added to unmarked surface samples from the Passage and subsequently re-extracted using successively cyclohexane, ethyl acetate and methanol with sonication, it was only recovered at 0.015% when originally added at 1%, whereas it was not recovered at all when added at 0.1%. Therefore, the limited efficacy of the detection method and the impossibility to obtain sufficient Apse samples restrict our ability to draw a solid conclusion on the presence of carotenoids in dark zone samples.

Third, the possibility that pigmented microorganisms may be controlled by antimicrobials produced by other microorganisms present on unmarked surfaces is a hypothesis in accordance with current data on (i) the occurrence there of biosynthetic genes for hydrogen cyanide, pyrrolnitrin, pyocyanin, and (ii) the enrichment in unmarked surfaces of metabolic pathways involved in the biosynthesis of tetracycline and siderophores. Bacterial genera such as Pseudomonas or Streptomyces, widely present in caves24,38, have the potential to secrete these antimicrobial compounds26,28,30. In addition, Pseudomonas strains isolated from unmarked surfaces of the Apse could inhibit growth of various pigmented fungi (e.g. Exophiala angulospora, Ochroconis lascauxensis) belonging to fungal genera evidenced in dark zones42,53.

In this work, we extended the analysis to include also dark zones with contrasted features, i.e. located elsewhere (in the Passage), on a distinct surface (an artificial limestone masonery bench), which received the same chemical treatments as in the Apse (formaldehyde, benzalkonium chloride, etc.) but also additional ones (myristalkonium chloride, 2-octyl-2H-isothiazol-3-one, Parmetol DF12 and 3% isothiazolinone6,12), and that formed much later (from 2016 on). Differences in substrate composition alone can impact microbial ecology in caves54,55,56,57,58 and may be relevant here. Not surprisingly, the metagenomic dataset indicated a significant difference in community composition, overall, between the Apse and the Passage (adonis: P = 0.001, R2 = 0.36). Since microbial community composition differed, it is not surprising that distinct dynamics were observed in relation to dark zone formation. In particular, the counter-selection of Pseudomonas in the Apse was not found here, as this genus represented only 0.3% in unmarked surfaces (and 3.5% in dark zones) of the Passage. In the Passage, the main features of dark zones were the selection of the classes Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria (as in the Apse) and the counter-selection of Acidobacteria class and Chitinophaga genus (unlike in the Apse). Against this background, some of the functional particularities identified in the Apse were also applicable to the Passage, i.e. (i) aromatic compound degradation genes and pathways well present both in and outside dark zones, (ii) the enrichment of dark zones in melanin synthesis pathway, with in the Passage a MAG affiliated to Hypocreales (Ascomycota) presenting a L-dopachrome biosynthesis pathway, and (iii) a decrease in siderophore biosynthesis pathways in dark zones. However, others were not relevant in the Passage, such as the enrichment of dark zones in biosynthetic genes for (i) carotenoids and (ii) hydrogen cyanide and pyocyanin, which occurred only in the Apse.

Overall, the formation of dark zones in the two rooms presents similarities, and we speculate that the following conceptual framework can be proposed for dark zone formation in Lascaux Cave (Fig. 7). First, BAC and other toxic chemicals applied on cave walls may be degraded by resistant microorganisms using aromatic compound degradation pathway(s), for instance via benzoyl-CoA and implicating Pseudomonas, Streptomyces or other bacteria. Second, BAC degradation products—including benzyldimethylamine, an intermediate almost 500 times less toxic than BAC59,60 and catechol—sustain microbial growth. Third, these degradation products may also provide (i) melanin precursors, for instance via the synthesis of L-dopachrome, subsequently transformed into 5,6-dihydroxyindole or 5,6-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylate, and (ii) metabolites for synthesis of carotenoids, which may be especially relevant in cave wall micro-environments where antagonistic microorganisms are less prevalent in the community. This proposition is compatible with previous hypotheses on other Lascaux alterations (black stains) attributed to melanized fungi, as outlined by Martin-Sanchez et al.61, Bastian et al.62, and Alabouvette and Saiz-Jimenez22.

The black arrows represent metabolic pathways identified in this study. The dotted arrows represent the metabolic pathways not identified in this study but expected to occur based on literature information. The blue arrows indicate the link between various benzene-like compounds that can derive from the degradation of BAC, which can then be transformed into carotenoids or L-dopachrome in dark zones. BAC: benzalkonium chloride; BDMA: benzyldimethylamine.

To conclude, dark zone alterations are of great concern for cave conservation, but their microbial features need clarification. The present metagenomic work fills a gap by revealing common secondary metabolism traits in two contrasted Lascaux locations, including microbial potentials for degradation of BAC biocides (thereby providing growth substrates), for synthesis of melanin or carotenoid (the latter might contribute to the dark shade of wall alterations), and production of antimicrobials that might regulate community composition. Understanding the taxonomic and functional processes involved in alteration formation is expected to better guide conservation strategies for this major Paleolithic site.

Methods

Samples collection and nucleic acid extraction

Lascaux Cave is located near Montignac in Périgord, South-West of France (N 45°03′13.087′′ and E 1°10′12.362′′). The cave has been closed for tourist visits since 1963 due to cave wall alterations. Human presence is now restricted and restrained to scientists with special authorization (from DRAC Nouvelle-Aquitaine, Ministry of Culture). The area chosen in this work included art-free natural limestone surfaces in the Apse, where dark zones started to form (2008), and nearby an artificial calcareous substrate (masonry benches) located at the end of the Passage, with dark zones that started in 2016 (Fig. 1). In both cases, dark zones keep growing. Samplings were carried out in December 2020 (only in the Apse) and April 2021 (both in Apse and Passage), in the upper inclined plane at the right side of the Apse and in the vertical part of the left bench of the Passage. Samples (on areas <1 cm2 each) were collected in triplicate, in dark zone alterations and on unmarked surfaces nearby (about 10 cm away) using sterile swabs in the Apse (because scalpels were not authorized) and scalpels in the Passage. Samples were placed in liquid nitrogen before leaving the cave and kept at −80 °C until DNA extraction.

DNA extraction was performed using the FastDNA SPIN Kit For Soil (MP Biomedicals, Illkirch, France), following the manufacturer’s instructions and adapted to low amounts of sample (80 s at a speed setting of 6.0 m/s followed by 15 min centrifugation at 4 °C). The elution step was achieved using two volumes of 50 µl elution buffer for each sample. The resulting DNA concentrations were quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA extracts were stored at −20 °C until library preparation.

Illumina NovaSeq 6000 metagenomic library preparation, sequencing and analysis

Eighteen metagenomic libraries were constructed for limestone and dark zone samples using a NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit (fragment size ~350 bp) (Illumina, San Diego, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Sequencing was performed by Genewiz company (Leipzig, Germany) using Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system 2 × 150 bp (at least 60 million reads per sample). Adapter sequences were removed and low-quality reads were filtered using Trimmomatic with default settings63. All metagenomes were then pooled and co-assembled using MEGAHIT64. Reads were mapped against contigs using Bowtie to estimate coverage65. Assembly quality is presented in Supplementary tables 1, 2 and 3. Gene prediction was achieved using Prodigal66 and rRNA was detected using barrnap67, before classification using RDP classifier68. Functional annotation was performed using KEGG database (v. 103.0)69. To allow sample comparisons, metagenomes were normalized to the lowest number of sequences (60,997,870 reads; see Supplementary Table 1 for details).

Reconstruction of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) was conducted using two different algorithms implemented in MetaBAT-270 and Maxbin 2.071 with contigs longer than 2000 bp. Both binning tools increased the number of bins during reconstruction. Redundant bins obtained from both binning algorithms were identified and removed using DAS Tool72. The completeness and contamination level of the bins were then evaluated using CheckM (for prokaryotic bins) and Busco (for microeukaryotic bins)73,74. Only bins with a contamination level under 5% and completeness above 75% were analyzed. Genetic composition of these MAGs was then explored using KEGG69, MetaCyc75 and COG76 based on genes identified in the co-assembly. Metabolic pathways in which 75% of the genes were present were considered and represented using “circlize” and ‘CircleHeatmap’ packages in R software77 (detailed information on selected functional genes is presented in Supplementary Table 5).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses (Student t tests, variance analysis) were carried out using R software78. Community composition was compared through Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling analysis (NMDS) computed at the taxa level, using “vegan” package in R 4.1.179. The procedure computes a stress value, which measures the difference between the ranks on the ordination configuration and the ranks in the original dissimilarity matrix for each replicate. Stress values below 0.1 are considered without risk of drawing false inferences, those under 0.2 are acceptable, but interpretation potential is limited with values >0.280. Permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was conducted using the “vegan” and “pairwiseAdonis” packages in R79,81 to test differences (P < 0.05) in overall community composition and to confirm NMDS results. Community structures were analyzed through the phyloseq R package82, with Tukey-HSD post-hoc tests. A Holm-Bonferroni correction was applied to P values to lower alpha risk.

Data availability

All sequences and codes are available upon request. The raw reads and bin sequences generated in this study are available in NCBI SRA database under BioProject PRJNA878937 and on FigShare (10.6084/m9.figshare.20626938). The bioinformatics pipelines and scripts used in this study have been deposited to the Github repository (https://github.com/Lascauxzelia/Bontemps_et_al_metagenomic).

References

Biot, V. Grottes et cavernes, Un patrimoine à (re)valoriser. Espac. Tour. Loisirs. 238, 15–21 (2006).

Cigna, A., Forti, P., Moreira, J. C. & Carvalho, C. N. Caves: The most important geotouristic feature in the world. Tour. Karst Areas. 6, 9–26 (2013).

Cigna, A. Tourism and show caves. Geomorphology 60, 217–233 (2016).

Ikner, L. A. et al. Culturable microbial diversity and the impact of tourism in Kartchner Caverns, Arizona. Microb. Ecol. 53, 30–42 (2007).

Portillo, M. C., Gonzalez, J. M. & Saiz-Jimenez, C. Metabolically active microbial communities of yellow and grey colonizations on the walls of Altamira Cave, Spain. J. Appl. Microbiol. 104, 681–691 (2008).

Martin-Sanchez, P. M., Miller, A. Z. & Saiz-Jimenez, C. Lascaux Cave: An example of fragile ecological balance in subterranean environments. In: (ed. Engel, A. S.) Microbial Life of Cave Systems, 279–301 (De Gruyter, 2015).

Bontemps, Z., Alonso, L., Pommier, T., Hugoni, M. & Moënne-Loccoz, Y. Microbial ecology of tourist Paleolithic caves. Sci. Total Environ. 816, 151492 (2021).

Russell, M. J. & MacLean, V. L. Management issues in a Tasmanian tourist cave: potential microclimatic impacts of cave modifications. J. Environ. Manage. 87, 474–483 (2008).

Dupont, J. et al. Invasion of the French Paleolithic painted cave of Lascaux by members of the Fusarium solani species complex. Mycologia 99, 526–533 (2007).

Gauchon, C., Jaillet, S. & Prud’homme, F. Dynamique de la construction topographique et toponymique à l’aven d’Orgnac (Ardèche, France). Collect. EDYTEM Cah. Géographie. 13, 157–176 (2012).

Chalmin, E. et al. Biotic versus abiotic calcite formation on prehistoric cave paintings: the Arcy-sur-Cure ‘Grande Grotte’ (Yonne, France) case. Geol. Soc. Lond. 279, 185–197 (2007).

Martin-Sanchez, P. M., Nováková, A., Bastian, F., Alabouvette, C. & Saiz-Jimenez, C. Use of biocides for the control of fungal outbreaks in subterranean environments: the case of the Lascaux Cave in France. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 3762–3770 (2012).

Papier, S., Baele, J. M., Gillan, D., Barriquand, L. & Barriquand, J. Manganese geomicrobiology of the black deposits from the Azé cave, Saône-et-Loire, France. Quaternaire 4, 297–305 (2011).

Lepinay, C. et al. Bacterial diversity associated with saline efflorescences damaging the walls of a French-decorated prehistoric cave registered as a World Cultural Heritage Site. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 130, 55–64 (2018).

Baquedano Estévez, C., Merino, L. M., de la Losa Román, A. & Duran Valsero, J. J. The lampenflora in show caves and its treatment: an emerging ecological problem. Int. J. Speleol. 48, 249–277 (2019).

He, J. et al. From surviving to thriving, the assembly processes of microbial communities in stone biodeterioration: a case study of the West Lake UNESCO World Heritage area in China. Sci. Total Environ. 805, 150395 (2022).

Lefèvre, M. La ‘Maladie Verte’ de Lascaux. Stud. Conserv. 19, 126–156 (1974).

Alonso, L. et al. Microbiome analysis of new, insidious cave wall alterations in the Apse of Lascaux Cave. Microorganisms 10, 2449 (2022).

Saiz-Jimenez, C. Microbiological and environmental issues in show caves. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 28, 2453–2464 (2012).

Dieser, M., Greenwood, M. & Foreman, C. M. Carotenoid pigmentation in antarctic heterotrophic bacteria as a strategy to withstand environmental stresses. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 42, 396–405 (2010).

Patrauchan, M. A. & Oriel, P. J. Degradation of benzyldimethylalkylammonium chloride by Aeromonas hydrophila sp. K. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94, 266–272 (2003).

Alabouvette, C. & Saiz-Jiménez, C. Écologie microbienne de la grotte de Lascaux. CSIC-Instituto de Recursos Naturales y Agrobiología de Sevilla (IRNAS) (2011).

Frey-Klett, P. et al. Bacterial-fungal interactions: hyphens between agricultural, clinical, environmental, and food microbiologists. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75, 583–609 (2011).

Maciejewska, M. et al. Assessment of the potential role of Streptomyces in cave moonmilk formation. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1181 (2017).

Alonso, L. et al. Anthropization level of Lascaux Cave microbiome shown by regional-scale comparisons of pristine and anthropized caves. Mol. Ecol. 28, 3383–3394 (2019).

Almario, J. et al. Distribution of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol biosynthetic genes among the Pseudomonas spp. reveals unexpected polyphyletism. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1218 (2017).

Howell, C. R. & Stipanovic, R. D. Control of Rhizoctonia solani on cotton seedlings with Pseudomonas fluorescens and with an antibiotic produced by the bacterium. Phytopathology 69, 480–482 (1979).

Michelsen, C. F. & Stougaard, P. Hydrogen cyanide synthesis and antifungal activity of the biocontrol strain Pseudomonas fluorescens In5 from Greenland is highly dependent on growth medium. Can. J. Microbiol. 58, 381–390 (2012).

Kong, D., Wang, X., Nie, J. & Niu, G. Regulation of antibiotic production by signaling molecules in Streptomyces. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2927 (2019).

Rangseekaew, P. & Pathom-aree, W. Cave Actinobacteria as producers of bioactive metabolites. Front. Microbiol. 10, 387 (2019).

Alonso, L. et al. Rock substrate rather than black stain alterations drives microbial community structure in the Passage of Lascaux Cave. Microbiome 6, 216 (2018).

Escobar-Zepeda, A., Vera-Ponce de León, A. & Sanchez-Flores, A. The road to metagenomics: from microbiology to DNA sequencing technologies and bioinformatics. Front. Genet. 6, 348 (2015).

Marcelino, V. R. et al. CCMetagen: comprehensive and accurate identification of eukaryotes and prokaryotes in metagenomic data. Genome Biol. 21, 103 (2020).

Falentin, H. et al. Guide pratique à destination des biologistes, bioinformaticiens et statisticiens qui souhaitent s’initier aux analyses métabarcoding. Cah. Tech. INRA. 2019, 1–23 (2019).

Saary, P., Mitchell, A. L. & Finn, R. D. Estimating the quality of eukaryotic genomes recovered from metagenomic analysis with EukCC. Genome Biol. 21, 244 (2020).

Gilbert, J. A. & Dupont, C. L. Microbial metagenomics: beyond the genome. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 3, 347–371 (2011).

Mendoza, M. L. Z. et al. Metagenomic analysis from the interior of a speleothem in Tjuv-Ante’s Cave, northern Sweden. PLoS One 11, e0151577 (2016).

Wiseschart, A., Mhuantong, W., Tangphatsornruang, S., Chantasingh, D. & Pootanakit, K. Shotgun metagenomic sequencing from Manao-Pee cave, Thailand, reveals insight into the microbial community structure and its metabolic potential. BMC Microbiol. 19, 144–156 (2019).

Bontemps, Z., Prigent-Combaret, C., Guillmot, A., Hugoni, M. & Moënne-Loccoz, Y. Dark-zone alterations expand throughout Paleolithic Lascaux Cave despite spatial heterogeneity of the cave microbiome. Environ. Microbiome 18, 31 (2023).

Dhami, N. K., Mukherjee, A. & Watkin, E. L. J. Microbial diversity and mineralogical-mechanical properties of calcitic cave speleothems in natural and in vitro biomineralization conditions. Front. Microbiol. 9, 10 (2018).

Kimble, J. C., Winter, A. S., Spilde, M. N., Sinsabaugh, R. L. & Northup, D. E. A potential central role of Thaumarchaeota in N-Cycling in a semi-arid environment, Fort Stanton Cave, Snowy River passage, New Mexico, USA. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 94, 173 (2018).

Bontemps, Z., Hugoni, M. & Moënne-Loccoz, Y. Microscale dynamics of dark zone alterations in anthropized karstic cave shows abrupt microbial community switch. Sci. Total Environ. 862, 160824 (2023).

Pereira, B. M. P. & Tagkopoulos, I. Benzalkonium chlorides: uses, regulatory status, and microbial resistance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 85, e00377–19 (2019).

Ertekin, E., Hatt, J. K., Konstantinidis, K. T. & Tezel, U. Similar microbial consortia and genes are involved in the biodegradation of benzalkonium chlorides in different environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 4304–4313 (2016).

Bontemps, Z., Hugoni, M. & Moënne-Loccoz, Y. Ecological impact of mechanical cleaning method to curb black stain alterations on Paleolithic cave walls. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 191, 105797 (2024).

Solano, F. Melanins: skin pigments and much more—types, structural models, biological functions, and formation routes. New J. Sci. 2014, e498276 (2014).

De la Rosa, J. M. et al. Structure of melanins from the fungi Ochroconis lascauxensis and Ochroconis anomala contaminating rock art in the Lascaux Cave. Sci. Rep. 7, 13441 (2017).

Azman, A. S., Mawang, C. I. & Abubakar, S. Bacterial pigments: The bioactivities and as an alternative for therapeutic applications. Nat. Prod. Commun. 13, 1747–1754 (2018).

Nicolaus, R. A. Melanins (Hermann, 1968).

Munoz-Munoz, J. L. et al. Generation of hydrogen peroxide in the melanin biosynthesis pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1794, 1017–1029 (2009).

Pawelek, J. M. Dopachrome conversion factor functions as an isomerase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 166, 1328–1333 (1990).

Ito, S. et al. Usefulness of alkaline hydrogen peroxide oxidation to analyze eumelanin and pheomelanin in various tissue samples: application to chemical analysis of human hair melanins. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 24, 605–613 (2011).

Alonso, L. et al. Microbiome analysis in Lascaux Cave in relation to black stain alterations of rock surfaces and collembola. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 15, 80–91 (2023).

Cañaveras, J. C., Sanchez-Moral, S., Soler, V. & Saiz-Jimenez, C. Microorganisms and microbially induced fabrics in cave walls. Geomicrobiol. J. 18, 223–240 (2001).

Barton, H. A. & Jurado, V. What’s up down there? Microbial diversity in caves microorganisms in caves survive under nutrient-poor conditions and are metabolically versatile and unexpectedly diverse. Microbe 2, 132–138 (2007).

Barton, H. A. & Northup, D. E. Geomicrobiology in cave environments: past, current and future perspectives. J. Cave Karst Stud. 69, 163–178 (2007).

Lavoie, K., Ruhumbika, T., Bawa, A., Whitney, A. & De Ondarza, J. High levels of antibiotic resistance but no antibiotic production detected along a gypsum gradient in Great Onyx Cave, KY, USA. Diversity 9, 42 (2017).

Espino del Castillo, A., Beraldi-Campesi, H., Amador-Lemus, P., Beltrán, H. I. & Borgne, S. L. Bacterial diversity associated with mineral substrates and hot springs from caves and tunnels of the Naica underground System (Chihuahua, Mexico). Int. J. Speleol. 47, 213–227 (2018).

Tezel, U., Tandukar, M., Martinez, R. J., Sobecky, P. A. & Pavlostathis, S. G. Aerobic biotransformation of n-tetradecylbenzyldimethylammonium chloride by an enriched Pseudomonas spp. community. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 8714–8722 (2012).

Tandukar, M., Oh, S., Tezel, U., Konstantinidis, K. T. & Pavlostathis, S. G. Long-term exposure to benzalkonium chloride disinfectants results in change of microbial community structure and increased antimicrobial resistance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 9730–9738 (2013).

Martin‐Sanchez, P. M. et al. The nature of black stains in Lascaux Cave, France, as revealed by surface‐enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J. Raman Spect. 43, 464–467 (2012).

Bastian, F., Alabouvette, C., Jurado, V. & Saiz-Jimenez, C. Impact of biocide treatments on the bacterial communities of the Lascaux Cave. Naturwissenschaften 96, 863–868 (2009).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Li, D., Liu, C. M., Luov, R., Sadakane, K. & Lam, T. W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly. Bioinformatics 31, 1674–1676 (2015).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 9, 357–359 (2012).

Hyatt, D. et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 119 (2010).

Seemann, T. Barrnap. Available from: https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap (2022).

Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M. & Cole, J. R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5261–5267 (2007).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Kang, D. D. et al. MetaBAT 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ 7, e7359 (2019).

Wu, Y. W., Tang, Y. H., Tringe, S. G., Simmons, B. A. & Singer, S. W. MaxBin: an automated binning method to recover individual genomes from metagenomes using an expectation-maximization algorithm. Microbiome 2, 26 (2014).

Sieber, C. M. K. et al. Recovery of genomes from metagenomes via a dereplication, aggregation and scoring strategy. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 836–843 (2018).

Parks, D. H., Imelfort, M., Skennerton, C. T., Hugenholtz, P. & Tyson, G. W. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25, 1043–1055 (2015).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Karp, P. D., Riley, M., Paley, S. M. & Pellegrini-Toole, A. The MetaCyc database. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 59–61 (2002).

Galperin, M. Y. et al. COG database update: focus on microbial diversity, model organisms, and widespread pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D274–D281 (2021).

Gu, Z. circlize: circular cisualization. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=circlize (2022).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/ (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community ecology package. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (2020).

Clarke, K. R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 18, 117–143 (1993).

Arbizu, P. M. pairwiseAdonis. Available from: https://github.com/pmartinezarbizu/pairwiseAdonis (2021).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. Phyloseq: a bioconductor package for handling and analysis of high-throughput phylogenetic sequence data. In: Proc. Pacific Symposium (eds Altman R. B. et al.) 235–246 (Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing, 2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Géraud, J.C. Portais, M. Mauriac (DRAC Nouvelle Aquitaine), and D. Henry-Lormelle (restorer team) for information and help, and Lascaux Scientific Board for useful discussions. This study was funded by DRAC Nouvelle Aquitaine (Bordeaux, France). The funder played no role in study design, data analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.B. contributed to sampling, acquired data, interpreted results, wrote the manuscript and prepared Figures and Tables; D.A. acquired data; S.V. acquired data; P.V. acquired data; G.C. interpreted results; S.M. interpreted results; Y.M.L. obtained funding, managed the project, designed the experiments, contributed to sampling, interpreted results and revised the manuscript; M.H. interpreted results and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bontemps, Z., Abrouk, D., Venier, S. et al. Microbial diversity and secondary metabolism potential in relation to dark alterations in Paleolithic Lascaux Cave. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 10, 121 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-024-00589-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-024-00589-3