Abstract

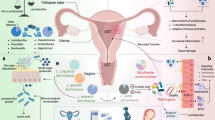

The lower female reproductive tract (FRT) hosts a complex microbial environment, including eukaryotic and prokaryotic viruses (the virome), whose roles in health and disease are not fully understood. This review consolidates findings on FRT virome composition, revealing the presence of various viral families and noting significant gaps in knowledge. Understanding interactions between the virome, microbiome, and immune system will provide novel insights for preventing and managing lower genital tract disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The lower portion of the female reproductive tract (FRT), the vagina and cervix, hosts a complex microbial environment composed of bacteria (bacteriome), archaea (archaeome), fungi (fungome), and viruses (virome). Their individual metabolisms and interactions contribute to the composition of the host local environment and influence the manifestation of gynecological disorders1. The great majority of FRT microbial investigations have focused on the bacteriome and used the term “microbiome” as a substitute for bacteriome. We follow this convention in the present report. The composition of the FRT microbiome has been shown to influence susceptibility to exogenous pathogens2,3 as well as to adverse reproductive outcomes such as preterm birth, miscarriage, and infertility2,3. The cervicovaginal microbiome likely also influences defense against malignant transformation at that site4,5.

Much less studied is the composition of the lower FRT virome. Unlike the microbiome, where analysis of different regions of the gene coding for bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA can provide a comprehensive description of the bacterial composition present in any individual, viral detection is exceedingly more complex. Recent advances in next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have propelled studies to identify components of the cervicovaginal virome worldwide6.

Despite these technological advancements, our understanding of FRT virome composition and its influence on cervicovaginal and reproductive health remains limited. Most studies have focused on the detection of select components of the virome, rather than providing a comprehensive analysis of total virus composition. Individual variability in both microbiome and virome composition in the FRT occurs due to a multitude of factors such as ethnicity, genetic background, environmental exposures, physiological status, and lifestyle variables including diet, hygiene practices, smoking and contraceptive methods6. This variability underscores the necessity to contextualize virome data within the broader spectrum of individual and environmental differences which directly affect FRT well-being.

The present systematic review aims to consolidate current knowledge of the complexity and variability of the FRT virome by providing a detailed overview of the available literature. Lastly, we seek to highlight key areas for future research.

Results

Literature search and study selection

The initial search identified 7495 records, of which 5559 duplicates were removed, leaving 1936 records for title and abstract screening. 1793 studies were excluded due to lack of viral data, involved non-human species, or did not focus on the FRT. Following a full-text assessment of 143 studies, 29 were excluded due to inappropriate study design or population, 65 for conducting only 16S bacterial ribosomal RNA sequencing, and 15 for being non-original articles. Consequently, 34 studies were included in the final analysis (Supplementary Note 2)7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. A flowchart of the literature search process is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Metadata Analysis

Among the 34 studies analyzed, cross-sectional designs predominated in 22 (64.7%), while only 12 studies (35.3%) employed a longitudinal design. Half of the studies (17) focused on reproductive-age cohorts, with the remainder involving mixed age groups (11 studies), adolescents (2 studies), premenopausal/menopausal women (2 studies), and 2 studies that did not specify the cohort age.

Various enrichment methods were employed, with targeted sequence capture and rolling circle amplification being the most common (14.7% and 11.7%, respectively). Three studies used other distinct enrichment methods, while 22 studies (67.7%) did not apply any enrichment method.

The majority of studies utilized silica membrane-based extraction methods (73.5%), followed by magnetic bead-based techniques (14.7%). Additionally, three studies used solvent-based methods, and one study employed a column-based method. DNA was the primary nucleic acid extracted in most studies (67.6%), with 10 studies (29.4%) extracting both DNA and RNA, and only one study focusing solely on RNA. Among the included studies, 8 (23.5%) incorporated an internal control to monitor potential background contamination, ensuring that viral contamination of reagents, equipment, and personnel was ruled out, while 26 (76.4%) did not specify any controls.

Illumina platforms were predominantly used for sequencing (88.2%), followed by BGI (5.9%). One study utilized Ion Torrent (2.9%), and another employed multiple sequencing platforms. Lactobacillus spp. analysis was performed in 29 studies (87.9%), with Lactobacillus predominance observed in 25 of these (86.2%).

The majority of studies made their metagenomic data publicly accessible, with 27 studies (79.5%) depositing data in ENA/SRA, 3 (8.8%) in CNGBdb, and 1 (2.9%) in EBI; however, 3 studies (8.8%) did not provide data availability. An overview of the key aspects and metadata from each included study is provided in Fig. 1.

Geographical distribution and sample characteristics

The geographical distribution of the studies was diverse, with a concentration in the Americas (35.3%) and the Western Pacific region (29.4%). European and African regions were represented by 5 studies each (14.7%), while 2 studies (5.9%) were conducted in the South-East Asian region.

Sample sizes and types varied significantly, with a total of 3477 samples sequenced across 13 different sample types. The most common sample types were cervical swabs/mucus (1378 samples), cervicovaginal swabs/secretion (734 samples), and vaginal swabs/secretion (629 samples). The distribution of sample types and their respective countries is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Study conditions and cohort control group usage

Regarding cohort control groups, 15 of 16 studies from women with a disorder or infection compared virome findings with healthy women, while only 3 of 17 studies on healthy pregnant or nonpregnant women or women undergoing a cycle of in vitro fertilization examined a control group. Among studies on women with vaginal dysbiosis (atypical vaginal microbiota), neoplasia, or viral infections, 8 studies (23.5%) investigated human papillomavirus (HPV)-related lesions, and individual studies addressed conditions such as vaginitis, candidiasis, HIV, and malignancy. None of the studies comparing the virome in women with a medical disorder with that of control women identified a viral signature that defined a specific condition. The only differences noted were a variation in the number of viruses identified, either an increase or a decrease depending on the specific study evaluated.

Viral families reported

A total of 79 different viral families were identified across the studies, comprising 55 eukaryotic and 24 prokaryotic viral families. The most frequently reported eukaryotic families were Papillomaviridae (97%), Anelloviridae (55.9%), and Orthoherpesviridae (47%). Among prokaryotic viruses, Siphoviridae (41%), Myoviridae (38%), and Podoviridae (29.4%) were the most common bacteriophage families identified. Notably, 67.6% of the studies reported the detection of viruses that could not be classified utilizing current criteria. The distribution of viral families across the 34 studies is depicted in Fig. 3.

Variability in virome composition across studies may reflect differences in study populations, methodologies, or sequencing techniques. To specifically address the virome in healthy women, we analyzed the 14 studies focused on healthy women. In this subgroup, Papillomaviridae was the most prevalent viral family (78.6%), followed by unclassified viruses (64.3%), and Anelloviridae, Orthoherpesviridae, and Siphoviridae, each with a reported prevalence of 42.9% (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Multiple viral species are clearly present in the lower FRT of most healthy women as well as in those with a variety of disorders. Their detection was certainly anticipated, based on the ubiquitous presence of prokaryotic viruses and eukaryotic viruses at every body site that has been investigated41. However, the composition of the virome can vary significantly across studies, even when similar sample types or clinical conditions are considered.

This variation may be attributed to methodological differences, including variations in extraction methods, the use of enrichment or purification techniques, and bacteriophages bioinformatics pipelines. Enrichment-based protocols offer the advantage of increasing sensitivity for detecting low-abundance viruses, enabling more targeted analyses. These approaches, though, have limitations, such as the potential loss of non-target viruses, the preferential detection of specific viral populations (e.g., circular viruses when using RCA), and the exclusion of integrated viruses, particularly when host genomes are depleted42. Additionally, during material extraction, the use of DNase and filtration can inadvertently remove small viral genomes or integrated viruses and filter out larger viruses, respectively34,43. Another concern is contamination, which can arise from environmental sources, other body sites, or experimental operations38. Moreover, sequence assignments can differ depending on the use of updated reference databases and catalogues across studies, impacting virome characterization and diversity analysis44.

It is likely that the continued evolution of more sophisticated protocols for viral detection and quantification will lead to an enhanced identification of different species and an improved understanding of their role in FRT health. A major challenge is to analyze associations between the presence and/or titer of specific viruses as a means to predict the onset of pathological conditions or even as targets for early intervention.

For example, it has been established that the bacterial composition of the vagina in reproductive-age women has a major influence on the occurrence of symptomatic vulvovaginal disorders such as bacterial vaginosis (BV), vulvovaginal candidiasis, aerobic vaginitis, among others45. Emerging evidence suggests that transkingdom interactions between bacteriophages and bacterial species may contribute to these conditions, particularly in bacterial vaginosis, where such dynamics could drive alterations in microbial communities and influence genital inflammation7,8. Bacteria-bacteriophage transkingdom analysis showed that women with genital inflammation and BV-associated bacteria (such as Mobiluncus, Mycoplasma, Gardnerella, Prevotella, and Sneathia) shared similar phage interaction profiles8. A study by Madere et al.11 demonstrated that bacteriophages present in vaginal swabs cluster into two distinct bacteriophage community groups based on their diversity. These groups were correlated with bacterial communities dominated by Lactobacillus spp. (low-diversity bacteriophages) and those dominated by non-Lactobacillus spp. (high-diversity bacteriophages), which included potentially harmful bacteria such as Gardnerella vaginalis spp. and Prevotella spp11. However, it remains unclear whether bacteriophage interactions with individual bacterial species in the FRT contribute to pathological changes. Some studies suggest that bacteriophage composition reflects differences between low and high diversity bacteriomes, but the exploration of these populations and interactions remains limited, and whether demographic or behavioral characteristics (e.g., a woman’s smoking status) influence this interaction7,11,21. Furthermore, it needs to be investigated whether exogenous administration of selective bacteriophages can prevent or reverse symptomatic disorders such as bacterial vaginosis.

The human body harbors a remarkable diversity of viral communities that play significant roles in shaping the host physiology and immune phenotype. Chronic systemic viruses, such as herpesviruses, polyomaviruses, anelloviruses, adenoviruses, and papillomaviruses, are known to interact continuously with the immune system19. These interactions can lead to immune activation through the recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns and antigens produced during viral replication or reactivation. As such, commensal viruses may contribute to upregulated innate immunity, providing protection against pathogenic viral or bacterial infections11,46,47. However, in certain contexts, such as in disease states or immunodeficiencies, the virome’s interaction with the immune system can be harmful6.

In the context of the vaginal virome, immunodeficiency can allow the establishment of viral infections that are less frequently detected in immunocompetent hosts, including genomoviruses (often associated with fungal co-infections), herpesviruses and a higher diversity of papillomaviruses39. The common presence of low-virulence viruses constantly stimulate mucosal host responses, with potential consequences for host resistance to other infections and susceptibility to diseases such as asthma, type 1 diabetes and Crohn’s disease, regarding respiratory and gastrointestinal tract virome studies48. This raises the possibility that commensal viruses can behave differently under conditions of altered immunity, such as genital inflammation or HIV co-infection.

Furthermore, the presence of endogenous viruses, such as human endogenous retroviruses, highlights the complex role the eukaryotic virome may play in gene expression regulation, mutagenic events, and potentially gene transfer. These interactions, along with host genetic variations, might generate phenotypes that cannot be fully understood by studying the host or viruses in isolation11.

Finally, the presence of large genome viruses (e.g., Poxviridae, Phycodnaviridae, Mimiviridae) has been reported in several FRT virome studies, yet their role in human health and disease remains largely unexplored. While only members of Poxviridae and Mimiviridae families have been linked to disease in humans, the pathogenic potential of other Megavirales members, and their influence in the vaginal environment, requires further investigation43,49.

Another area almost entirely lacking investigation is the characterization and the role played by viruses that can infect other microorganisms present in the vaginal environment. We lack information about the composition of the vaginal mycobiota and its relation with the virome, including whether viruses capable of infecting Candida albicans, are present in the FRT of some women and whether their occurrence influences the development or recurrence of vulvovaginal candidiasis. A virus that infects the protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis, has been identified, and its presence accentuates clinical disease in infected women50.

Torque teno virus (TTV), a member of the Anelloviridae family, is typically regarded as a non-pathogenic endogenous virus commonly found in the majority of individuals. Its titer in biological fluids is known to vary depending on the immune status of the host51. Some studies have reported an increase in the abundance of Anelloviridae species in cases of genital inflammation due to HPV8,9,39, but their role in health and disease remains largely unexplored. It would be of interest to determine whether TTV titer in the lower FRT could serve as a sensitive indicator of local immune status and a predictor of various pathological conditions, such as recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, cervical dysplasia, sexually transmitted infections, and pregnancy complications.

Infection of exocervical cells by pathogenic HPV types is a requisite early step in the development of cervical cancer52. In two studies investigating the FRT virome, HPV infection was shown to significantly influence the reduction of both viral and bacterial diversity, particularly in the context of inflammation17,33. Genital inflammation, in turn, has been linked to an increased risk of cervical cancer progression and a heightened susceptibility to acquiring sexually transmitted infections53,54. Moreover, virome studies facilitated the identification of novel HPV types, which may contribute to tumorigenesis and other associated diseases13,40. It remains to be determined whether the host immune system’s ability to spontaneously clear an HPV infection is influenced by the co-occurrence of other viral and/or bacterial entities at the site. Conversely, the presence of another virus or bacterial species could potentially facilitate HPV persistence and increase infectivity. In an animal study it has been reported that the presence of a seemingly innocuous herpesvirus potentiated the pathogenic effect of a bacterial infection, leading to premature labor55.

A study of DNA eukaryotic viruses in pregnant women has reported that while there was no association between the presence of a specific viral species and adverse outcome, there was an association between preterm birth and the presence of multiple viral species on the FRT, with changes in virome diversity mirroring those observed in the bacterial microbiome19. In contrast, another study that performed both DNA and RNA viral analysis observed that genital inflammation was associated with decreased virome richness and an increased abundance of Anelloviridae species in non-pregnant women8. A third study that also analyzed both DNA and RNA viruses at species level found greater viral diversity in healthy pregnant women compared to pregnant women with vaginitis38. These associations between viral diversity and adverse consequences require further investigation.

Metagenomic studies are increasingly identifying new viruses, broadening our understanding of viral diversity and its roles in health and disease. Despite this progress, many viruses remain unclassified, and their functional roles are poorly understood. The taxonomic level of reporting is a critical factor that can influence the interpretation of results, as differences in reporting at the family, genus, or species level can lead to variations in how viral diversity and its association with health outcomes are understood. Characterizing these viruses, particularly those targeting vaginal pathogens, is crucial for exploring their potential in phage therapy. Comprehensive research is needed to fully characterize the FRT virome, as RNA virus detection remains challenging due to the instability of stored RNA and the complexity of sequencing assays14. Additionally, the development of more robust viral databases and updated bioinformatics pipelines has improved the accuracy of virome analyses, highlighting the importance of public data sharing56. There is also a lack of comparative analyses of virome composition among different ethnic groups to better understand potential virome variability influenced by genetic and environmental factors. Investigating the interactions between the virome, microbiome, and immune system is also essential for gaining deeper insights into their genomic contributions to women’s health.

In conclusion, multiple species of eukaryotic and prokaryotic viruses reside in the lower FRT of healthy women. The specific viral entities present in any individual woman vary due to environmental and genetic variables. The role of specific viruses in maintaining reproductive tract health and the mechanisms leading to their contribution to pathology remains largely unexplored.

Methods

Literature search and selection criteria

To provide a comprehensive overview of studies employing viral metagenomic NGS in the female reproductive tract, a systematic review was conducted. Relevant studies were identified across five electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. Literature published up to April 14th, 2024, was included. Search terms were validated using the Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS, WHO, 2024), with the search strategy utilized provided in the Supplementary Note 1. This study adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)57 guidelines and was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; ID: CRD42021286295).

Study management and screening were facilitated by Rayyan web-based software. After duplicate removal, two reviewers screened titles and abstracts. Articles that passed this initial screening were subjected to a full-text review independently. No restrictions were placed on language or publication date during the selection process. Studies were included if they performed the characterization of the human FRT virome via metagenomic NGS. Exclusion criteria were: (1) absence of viral data (2) animal studies (3) studies in the form of conference abstracts, letters, or review articles; and (4) studies published solely as preprints without subsequent peer-reviewed publication.

Data extraction and analysis

For each included study, the following data were extracted: first author, journal, year of publication, study design (cross-sectional or longitudinal), cohort age, health conditions, sampling date and size, specimen type, geographical origin, Lactobacillus spp. dominance (where bacteriome analysis was conducted), and detected viral families. Viral taxonomy was cross-referenced using the NCBI Taxonomy Browser. Certain viral families reported in the original studies have undergone reclassification by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Specifically, the families Siphoviridae, Myoviridae, and Podoviridae were abolished in 2021, while Herpesviridae and Totiviridae were renamed to Orthoherpesviridae (2022) and Orthotoviridae (2023), respectively. Nevertheless, the original nomenclature used in each study was retained to preserve the systematic consistency of this review, alongside the most recent taxonomic context. Geographical data were stratified according to World Health Organization (WHO) regions: African Region, Americas Region, European Region, South-East Asia Region, and Western Pacific Region.

Technical and methodological metadata were also extracted, including enrichment and extraction method, type of nucleic acid extracted, sequencing platform utilized, application of internal controls, and data availability. Enrichment methods were categorized into five groups: Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA), targeted sequence capture, viral particle precipitation, methylation-based affinity enrichment, and filtration and centrifugation with RCA. Extraction methods were categorized into four groups: silica-membrane based, solvent-based, magnetic beads based, and column-based. Sequencing platforms were grouped into three categories: Illumina, Ion Torrent, and BGI (Beijing Genomics Institute). Data availability was determined by whether the study deposited metagenomic data in public repositories such as ENA/SRA (European Nucleotide Archive and Sequence Read Archive), CNGBdb (China National GeneBank DataBase), or EBI (European Bioinformatics Institute).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Madere, F. S. & Monaco, C. L. The female reproductive tract virome: understanding the dynamic role of viruses in gynecological health and disease. Curr. Opin. Virol. 52, 15–23 (2022).

Happel, A.-U., Varsani, A., Balle, C., Passmore, J.-A. & Jaspan, H. The vaginal virome—balancing female genital tract bacteriome, mucosal immunity, and sexual and reproductive health outcomes? Viruses 12, 832 (2020).

Punzón-Jiménez, P. & Labarta, E. The impact of the female genital tract microbiome in women health and reproduction: a review. J. Assist Reprod. Genet. 38, 2519–2541 (2021).

Morikawa, A. et al. Altered cervicovaginal microbiota in premenopausal ovarian cancer patients. Gene 811, 146083 (2022).

Nguyen, H. D. T. et al. Relationship between human papillomavirus status and the cervicovaginal microbiome in cervical cancer. Microorganisms 11, 1417 (2023).

Bhagchandani, T., Nikita, Verma, A. & Tandon, R. Exploring the human virome: composition, dynamics, and implications for health and disease. Curr. Microbiol 81, 16 (2024).

Jakobsen, R. R. et al. Characterization of the vaginal DNA virome in health and dysbiosis. Viruses 12, 1143 (2020).

Kaelin, E. A. et al. Cervicovaginal DNA virome alterations are associated with genital inflammation and microbiota composition. mSystems 7, e0006422 (2022).

Britto, A. M. A. et al. Microbiome analysis of Brazilian women cervix reveals specific bacterial abundance correlation to RIG-like receptor gene expression. Front. Immunol. 14, 1147950 (2023).

Li, F. et al. The metagenome of the female upper reproductive tract. Gigascience 7, giy107 (2018).

Madere, F. S. et al. Transkingdom analysis of the female reproductive tract reveals bacteriophages form communities. Viruses 14, 430 (2022).

Gosmann, C. et al. Lactobacillus-deficient cervicovaginal bacterial communities are associated with increased HIV acquisition in young South African women. Immunity 46, 29–37 (2017).

Ameur, A. et al. Comprehensive profiling of the vaginal microbiome in HIV positive women using massive parallel semiconductor sequencing. Sci. Rep. 4, 4398 (2014).

Happel, A.-U. et al. Presence and persistence of putative lytic and temperate bacteriophages in vaginal metagenomes from South African adolescents. Viruses 13, 2341 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Maternal and neonatal viromes indicate the risk of offspring’s gastrointestinal tract exposure to pathogenic viruses of vaginal origin during delivery. mLife 1, 303–310 (2022).

Du, L. et al. Temporal and spatial differences in the vaginal microbiome of Chinese healthy women. PeerJ 11, e16438 (2023).

Sasivimolrattana, T. et al. Human virome in cervix controlled by the domination of human papillomavirus. Viruses 14, 2066 (2022).

Pagan, L. et al. The vulvar microbiome in lichen sclerosus and high-grade intraepithelial lesions. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1264768 (2023).

Wylie, K. M. et al. The vaginal eukaryotic DNA virome and preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 219, 189.e1–189.e12 (2018).

Elnaggar, J. H. et al. Characterization of vaginal microbial community dynamics in the pathogenesis of incident bacterial vaginosis, a pilot study. Sex. Transm. Dis. 50, 523–530 (2023).

Yang, Q. et al. The alterations of vaginal microbiome in HPV16 infection as identified by shotgun metagenomic sequencing. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 10, 286 (2020).

Gonzalez-Bosquet, J. et al. Bacterial, archaea, and viral transcripts (BAVT) expression in gynecological cancers and correlation with regulatory regions of the genome. Cancers (Basel) 13, 1109 (2021).

Li, C. et al. Comparative analysis of the vaginal bacteriome and virome in healthy women living in high-altitude and sea-level areas. Eur. J. Med Res 29, 157 (2024).

Sola-Leyva, A. et al. Mapping the entire functionally active endometrial microbiota. Hum. Reprod. 36, 1021–1031 (2021).

Bommana, S. et al. Metagenomic shotgun sequencing of endocervical, vaginal, and rectal samples among fijian women with and without chlamydia trachomatis reveals disparate microbial populations and function across anatomic sites: a pilot study. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e0010522 (2022).

Ferretti, P. et al. Mother-to-infant microbial transmission from different body sites shapes the developing infant gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 24, 133–145.e5 (2018).

Lloyd-Price, J. et al. Strains, functions and dynamics in the expanded Human Microbiome Project. Nature 550, 61–66 (2017).

Toh, E. et al. Sexual behavior shapes male genitourinary microbiome composition. Cell Rep. Med 4, 100981 (2023).

Wylie, T. N., Schrimpf, J., Gula, H., Herter, B. N. & Wylie, K. M. Comparison of metagenomic sequencing and the NanoString nCounter analysis system for the characterization of bacterial and viral communities in vaginal samples. mSphere 7, e0019722 (2022).

Wylie, K. M. et al. Metagenomic analysis of double-stranded DNA viruses in healthy adults. BMC Biol. 12, 71 (2014).

Jie, Z. et al. Life history recorded in the vagino-cervical microbiome along with multi-omes. Genomics Proteom. Bioinforma. 20, 304–321 (2022).

Chen, C. et al. Cervicovaginal microbiome dynamics after taking oral probiotics. J. Genet. Genomics 48, 716–726 (2021).

Sasivimolrattana, T. et al. Cervical microbiome in women infected with HPV16 and high-risk HPVs. Int J. Environ. Res Public Health 19, 14716 (2022).

Arroyo Mühr, L. S., Dillner, J., Ure, A. E., Sundström, K. & Hultin, E. Comparison of DNA and RNA sequencing of total nucleic acids from human cervix for metagenomics. Sci. Rep. 11, 18852 (2021).

Eskew, A. et al. Association of the eukaryotic vaginal virome with prophylactic antibiotic exposure and reproductive outcomes in a subfertile population undergoing in vitro fertilisation: a prospective exploratory study. BJOG 127, 208–216 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Altered vaginal eukaryotic virome is associated with different cervical disease status. Virol. Sin. 38, 184–197 (2023).

da Costa, A. et al. Identification of bacteriophages in the vagina of pregnant women: a descriptive study. BJOG 128, 976–982 (2021).

Zhang, H.-T., Wang, H., Wu, H.-S., Zeng, J. & Yang, Y. Comparison of viromes in vaginal secretion from pregnant women with and without vaginitis. Virol. J. 18, 11 (2021).

Siqueira, J. et al. Composite analysis of the virome and bacteriome of HIV/HPV co-infected women reveals proxies for immunodeficiency. Viruses 11, 422 (2019).

Happel, A.-U. et al. Cervicovaginal human papillomavirus genomes, microbiota composition and cytokine concentrations in South African adolescents. Viruses 15, 758 (2023).

Liang, G. & Bushman, F. D. The human virome: assembly, composition and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 19, 514–527 (2021).

Parras-Moltó, M., Rodríguez-Galet, A., Suárez-Rodríguez, P. & López-Bueno, A. Evaluation of bias induced by viral enrichment and random amplification protocols in metagenomic surveys of saliva DNA viruses. Microbiome 6, 119 (2018).

Colson, P. et al. Evidence of the megavirome in humans. J. Clin. Virol. 57, 191–200 (2013).

Wu, Y. & Peng, Y. Ten computational challenges in human virome studies. Virol. Sin. (2024).

France, M., Alizadeh, M., Brown, S., Ma, B. & Ravel, J. Towards a deeper understanding of the vaginal microbiota. Nat. Microbiol 7, 367–378 (2022).

Virgin, H. W. The virome in mammalian physiology and disease. Cell 157, 142–150 (2014).

Duerkop, B. A. & Hooper, L. V. Resident viruses and their interactions with the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 14, 654–659 (2013).

Foxman, E. F. & Iwasaki, A. Genome–virome interactions: examining the role of common viral infections in complex disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 9, 254–264 (2011).

Tokarz-Deptuła, B., Niedźwiedzka-Rystwej, P., Czupryńska, P. & Deptuła, W. Protozoal giant viruses: agents potentially infectious to humans and animals. Virus Genes 55, 574–591 (2019).

Graves, K., Ghosh, A., Kissinger, P. & Muzny, C. Trichomonas vaginalis virus: a review of the literature. Int J. STD AIDS 30, 496–504 (2019).

Tozetto-Mendoza, T. R., Braz-Silva, P. H., Giannecchini, S. & Witkin, S. S. Editorial: Torquetenovirus: predictive biomarker or innocent bystander in pathogenesis. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 10, (2023).

Bhattacharjee, R. et al. Mechanistic role of HPV-associated early proteins in cervical cancer: Molecular pathways and targeted therapeutic strategies. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 174, 103675 (2022).

Łaniewski, P. et al. Linking cervicovaginal immune signatures, HPV and microbiota composition in cervical carcinogenesis in non-Hispanic and Hispanic women. Sci. Rep. 8, 7593 (2018).

Masson, L. et al. Genital inflammation and the risk of HIV acquisition in women. Clin. Infect. Dis. 61, 260–269 (2015).

Cardenas, I. et al. Placental viral infection sensitizes to endotoxin-induced pre-term labor: a double hit hypothesis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 65, 110–117 (2011).

Huang, L. et al. A multi-kingdom collection of 33,804 reference genomes for the human vaginal microbiome. Nat. Microbiol 9, 2185–2200 (2024).

Shamseer, L. et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 349, g7647–g7647 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Virology laboratory (LIM-52) at the Instituto de Medicina Tropical, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.H. conceptualized the project, conducted investigations, performed formal analysis, curated data and developed the methodology, performed validation and visualization, wrote the original draft, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. H.G.O.P. conducted investigations, formal analysis and validation, and reviewed the original draft. A.C.d.C. performed formal analysis and reviewed the manuscript. T.R.T.-M. performed formal analysis, reviewed the original draft and the manuscript. M.C.M.-C. supervised the project, reviewed the original draft and the manuscript, and secured funding. S.S.W. supervised the project, performed formal analysis, wrote the original draft, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Honorato, L., Paião, H.G.O., da Costa, A.C. et al. Viruses in the female lower reproductive tract: a systematic descriptive review of metagenomic investigations. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 10, 137 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-024-00613-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-024-00613-6