Abstract

Microbial community responses to environmental stressors are often characterised by assessing changes in taxonomic structure, but such changes, or lack thereof, may not reflect functional changes that are critical to ecosystem processes. We investigated the individual and combined effects of nutrient enrichment ( + 10 mg/L N, + 1 mg/L P) and salinisation ( + 15 g/L NaCl)—key stressors in freshwater systems—on the taxonomic structure and metabolic function of benthic microbial communities using 1000 L open freshwater ponds established >10 years ago in the field. Combined stressors drove strong decreases in maximum and mean total carbon metabolic rates and shifted carbon metabolic profiles compared to either stressor individually and compared to ambient conditions. These metabolic functional changes did not recover through time and occurred without significant alterations in bacterial community taxonomic structure. These results imply that critical functions, including organic carbon release, are likely to be impaired under multiple stressors, even when taxonomic structure remains stable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Community structure and function are central properties of natural systems used to understand and quantify ecosystem change under environmental stress1,2,3. Microbial communities underpin key ecosystem functions (e.g. nutrient and carbon cycling, primary productivity); thus, changes in microbial community structure and function can be indicators of ecosystem responses to environmental stress4,5,6,7. Changes in the taxonomic structure of microbial communities, which we define as the composition and abundances of taxa, can directly impact microbial functions, which we define as the sum of the activities performed by all members of the community, which in turn can lead to broader ecosystem-level changes8,9,10. For example, shifts in bulk soil microbial community structure under climate change-related stressors can result in changes to decomposition rates of organic carbon in soils11,12. However, stressors can also affect community structure and function independently of each other. Functional changes may occur without corresponding shifts in community structure when stressors induce sub-lethal physiological effects on individual organisms13, for example, where stressors induce dormancy in a portion of the community14. Conversely, structural changes of microbial communities might not translate into functional changes if, for example, the new/modified microbial community can still perform the same functions, i.e. the system exhibits functional redundancy15,16. Both scenarios can be common in microbial communities due to their high taxonomic diversity, physiological plasticity and rapid reproduction rates15,16,17,18. Furthermore, disturbances can affect the structure and function of microbial communities in different ways, resulting in different trajectories over time8,19,20,21. For example, in aquatic systems, bacterial community structure tends to continue to drift away from the pre-disturbance state after a disturbance22, while community function often recovers through time23. Despite this complexity, predictions about the functional consequences of environmental stressors frequently rely on assessments of microbial community structure alone which may not translate into changes in microbial function, limiting our ability to accurately predict and mitigate the effects of environmental stressors21,24.

Freshwater lakes and ponds are important habitats that support biodiversity, primary productivity, carbon cycling and water supply25,26. Climate and land-use changes are causing multiple environmental stressors to interact, leading to novel and unpredictable ecological responses in the community structure and function of freshwater ecosystems19,27,28,29,30. Multiple freshwater stressors interact to affect community composition across various levels of biological organisation, for example macroinvertebrates31,32, diatoms29, periphyton30, bacterioplankton33, bacteria34 and fungi35, and drive non-additive effects on important functions, for example, organic matter decomposition27,28, organic substrate utilization36 and phosphorous uptake32. While stressor interactions have been studied extensively in freshwater systems, combined effects of stressor pairings involving salinisation, an emerging freshwater threat, remain understudied (for notable exceptions, see32,37) and have been highlighted as a significant research priority38. In addition, most studies testing the effects of freshwater stressors apply treatments to developing communities or newly developed communities (i.e. <1 yr of succession), limiting our understanding of how stressors affect well established communities reflective of realistic field scenarios.

Freshwater salinisation is increasingly occurring across a diverse range of environmental contexts due to climate change, mining, agricultural runoff, freshwater extraction, drought and other human activities, and is threatening freshwater ecosystems globally38. Salinisation and nutrient enrichment often occur in combination32,37, yet their combined effects on freshwater microbial communities are not well understood. This is important because changes to microbial community structure and function may translate into changes in ecosystem function6, and understanding the changes in microbial community structure and function under these stressors individually and in combination may inform management, for example, in the design of meaningful microbial bioindicators39. Increased salinity causes osmotic stress which typically reduces microbial growth, biofilm formation and overall microbial abundance24,40,41, alters community structure in favour of euryhaline organisms40,42,43 and decreases rates of key microbially mediated functions, such as organic carbon decomposition44,45,46. In contrast, increased nutrient concentrations typically increase microbial biomass, bacterial growth rates and biofilm thickness47,48,49, shift community structure in favour of fast growing copiotrophic bacterial taxa resulting in homogenisation50,51,52 and increase rates of key microbial functions such as production of carbon degrading extracellular enzymes, organic carbon decomposition and community respiration49,53,54. Given the effects of these stressors on microbial communities are mediated by different mechanisms, their interactive effects may result in complex structural and/or functional responses which are hard to predict by studying each of these stressors in isolation. This is particularly important in the context of freshwater quality monitoring where there is increasing interest in the utility of microbial bioindicators under multiple stressor scenarios39. Although molecular advances have meant microbial community composition data can be readily obtained using culture-independent methods, approaches that quantify functional groups, genes or direct functional measures may be more meaningful indicators of environmental stress than broader community indices (e.g. richness or diversity)39.

Generally, the magnitude of functional changes in an ecosystem is predicted to increase with the number of environmental stressors experienced55,56. The effects of multiple environmental stressors can be additive (i.e. the sum of the individual stressor effects)54 or can result in more complex, non-additive interactions19,57,58,59,60. These non-additive interactions can be positively or negatively synergistic (where the combined effect is more positive, or more negative, than predicted additively, respectively), or positively or negatively antagonistic (where the combined effect is less positive, or less negative, than predicted additively)61. Multiple stressor effects can change through time36 and differ depending on the context and the functions being quantified. For example, inorganic nutrient enrichment and increased temperature may have synergistic effects on microbial organic carbon decomposition rates in soils (i.e. the magnitude of change is greater than the sum of the individual stressor effects)62, but antagonistic effects on microbial productivity in aquatic systems (i.e. the magnitude of change is less than the sum of the individual stressor effects)63. Critically, most studies investigating microbial community responses to multiple stressors have been conducted using simplified communities and in controlled environmental conditions (but for an example of a multiple stressor experiment in complex freshwater communities, see27). Thus, to better predict how nutrient enrichment and salinisation impact the structure and function of complex microbial communities in realistic settings, further research is needed under realistic and ecologically relevant environmental change scenarios with established communities (i.e. >1 year of succession).

This study assessed the independent and interactive effects of two relevant stressors in freshwater systems—salinisation and nutrient enrichment—on benthic microbial communities in semi-natural freshwater ponds (open ponds with established communities in the field for >10 years)64,65. Specifically, we determined whether microbial community functional changes in response to environmental stressors occurred in conjunction with, or independently from, community structural changes and whether this was consistent among stressor types, stressor combination and at multiple time points. We manipulated concentrations of salts and inorganic nutrients in the ponds, both individually and in combination. Microbial community structure and bacterial abundance were quantified via amplicon sequencing and qPCR of the 16S rRNA gene and measurements of the concentration of phototrophic groups (green algae, diatoms and cyanobacteria) using pigment fluorescence. Community-level function was quantified using community level physiological profiling of metabolic rates on a diverse array of carbon sources and via measurements of community respiration rate, net and gross primary productivity, biofilm biomass and photosynthetic efficiency, providing a comprehensive representation of key microbial functions in freshwater systems66,67,68.

Elevated salinity and nutrient enrichment can both have strong effects on freshwater microbial community taxonomic structure, and environmental stress-induced changes to taxonomic structure generally strengthen through time. In contrast, these stressors generally have opposing functional consequences (elevated salinity tends to decrease overall microbial community activity, while nutrient enrichment tends to increase activity) which often recover through time. Therefore we hypothesised that both increased salinity and nutrients would change microbial community structure compared to ambient conditions, and that the magnitude of these structural shifts would increase through time, indicating community drift, and be greatest where both stressors were combined. Given the differences in mechanisms by which each of these stressors generally affect microbial communities, we also predicted that increased salinity would decrease rates of microbial function, including the rates of carbon metabolism, community respiration, community net and gross primary productivity, biofilm biomass and photosynthetic efficiency, while increased nutrients would increase these microbial functional metrics, resulting in a smaller effect on microbial function where both stressors were combined. Finally, we predicted that the magnitude of functional changes would decrease through time, indicating recovery.

Results

Treatment pond conditions

Conductivity was significantly higher in elevated salinity (S) and combined stressor (SN) ponds compared to ambient (A) and elevated nutrients (N), and this was consistent through time (F6, 20 = 7.10, p <0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2). In the elevated salinity and combined stressor treated ponds, conductivity was significantly lower on day 90 compared to day 1 for both treatments and compared to day 30 under elevated salinity (F6, 20 = 7.10, p <0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2). Oxygen concentration was significantly lower in elevated nutrients ponds (N) compared to elevated salinity (S) and ambient ponds (A) (F3, 10 = 4.89, p <0.03) (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2). Oxygen concentration was also significantly higher on day 30 compared to day 1 and day 90 (F2, 20 = 34.17, p <0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2). There were no significant effects of treatment or time on pond pH or chlorophyll a concentration, although there was a trend for higher chlorophyll a concentration under the elevated nutrients and ambient treatments compared to the elevated salinity and combined stressor treated ponds (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2). 30 days after nutrients were added to ponds, phosphate concentrations were higher in ambient ponds than all other treatments (F3, 12 = 7.292, p <0.01) (Supplementary Tables 3, 4, Supplementary Fig. 3). Concentrations of nitrate were significantly higher in the combined stressor (SN) treatment compared to all other treatments (F3, 12 = 8.378, p <0.01), while concentrations of nitrite were below detectable concentrations ( <0.025 mg/L) for all but one pond (Supplementary Table 3).

Bacterial community structure

There were no significant effects of stressors, either alone or combined, on bacterial community structure or composition and this was consistent at each sampling time (Supplementary Tables 5, 6, Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 4). Similarly, bacterial diversity (Shannon’s index) and total bacterial abundance did not significantly differ among treatments or though time (Supplementary Tables 7, 8, Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 5). However, there was a non-significant trend for lower bacterial diversity in the combined (SN) treatment compared to ambient (A) on day 1 (Fig. 1).

A nMDS ordination on square root transformed Bray Curtis distances calculated on absolute abundances of ASVs (stress = 0.192). B Mean Shannon’s diversity calculated on absolute ASV abundances ( ± SE) (n = 3, except SN treatment on Day 7 and Day 30 where n = 4). An nMDS combining points from samples at each time into one panel is found in Supplementary Fig. 4.

Concentration of groups of phototrophic organisms

There was an interaction between treatment and time for concentration of green algae (F9,30 = 2.63, p <0.02; Supplementary Table 9), with lower concentrations under the combined (SN) treatment compared to the elevated salinity treatment (S) at day 7, and lower concentrations under the combined (SN) treatment and the elevated salinity (S) treatment compared to the elevated nutrient treatment (N) at day 30 (Supplementary Table 9, Fig. 2). Green algae concentrations also followed different temporal patterns between treatments (Supplementary Table 9, Fig. 2). Under ambient conditions (A) green algae concentrations were significantly higher on day 30 compared to day 1 and 90, under elevated nutrients (N) they were significantly higher on day 1 and 30 compared to day 90, and under elevated salinity (S) they were significantly higher on day 7 compared to day 1, 30 and 90 (Supplementary Table 9, Fig. 2). No differences among treatments were observed for concentrations of diatoms or cyanobacteria, despite a trend of higher concentrations of cyanobacteria under the elevated salinity treatment (S) at day 7, and under nutrient enrichment treatment (N) at day 30 (Supplementary Table 9, Fig. 2). Cyanobacteria concentrations changed significantly through time (F3, 30 = 4.25, p <0.02), increasing significantly between day 1 and 7, remaining stable through to day 30, and decreasing significantly between day 30 and 90 (Supplementary Table 9, Fig. 2).

Community level physiological profiles and metabolic rates

There was an effect of treatment on the Community Level Physiological Profiles (CLPPs) of benthic microbial communities (pseudo-F3,19 = 1.91, p <0.02), which was independent of time (Supplementary Table 10, Fig. 3). CLLPs of communities under the combined elevated nutrients and salinity (SN) treatment differed from all other treatments, which did not differ from each other (Supplementary Table 10, Fig. 3).

There was an interaction between treatment and time for total maximum (F6,1328 = 2.14, p <0.05) and mean carbon metabolic rates (F6,1338 = 9.74, p <0.05) of benthic bacterial communities (Supplementary Table 11; Fig. 4). Maximum metabolic rate was consistently lower in the combined stressor treatment (SN) than in all other treatments, although at days 7 and 30 SN did not differ from the elevated salinity treatment (S; Supplementary Table 11, Fig. 4). At day 30, maximum metabolic rate in the elevated nutrient treatment (N) was significantly higher than all other treatments (Supplementary Table 11, Fig. 4). Similarly for mean metabolic rate, the combined (SN) treatment had consistently lower metabolism than all other treatments (Supplementary Table 11, Fig. 4).

When assessing maximum metabolic rates independently for each carbon group, microbial communities under the combined elevated salinity and nutrient treatment (SN) generally had lower maximum metabolic rates than all other treatments for carbohydrates (F3,12 = 5.15, p <0.02), carboxylic acids (F3,12 = 3.98, p <0.04) and amino acids (F3,11 = 5.54, p <0.02) and this was consistent through time (Supplementary Table 12, Fig. 5). No differences in maximum metabolic rate among treatments were found for polymers, phenols or amines (Supplementary Table 12). Bacterial communities under the elevated nutrient (N) treatment had higher mean metabolic rates at day 30 than all other treatments for carbohydrates (F6,379 = 5.22, p <0.001), carboxylic acids (F6,335 = 2.41, p <0.03) and polymers (F6,157 = 2.16, p <0.05), but no differences among treatments were found for amino acids, phenols or amines (Supplementary Table 12, Supplementary Fig. 8).

Values are maximum slopes of average well colour development absorbance values divided by ambient controls. Relative maximum slope values were square-root transformed and scaled by centring them around the ambient mean slope which was set at 0. Relative mean metabolic rates are seen in Supplementary Fig. 8.

Productivity, chlorophyll a and photosynthesis

There were no significant differences in community respiration (CR), Net Primary Productivity (NPP), Gross Primary Productivity (GPP), CR efficiencies, NPP efficiencies, GPP efficiencies, total chlorophyll a concentration or photosynthetic yield of benthic freshwater microbial communities among treatments (Supplementary Tables 13, 14, Supplementary Figs. 9, 10). Total chlorophyll a concentrations changed significantly through time (F3, 30 = 7.56, p <0.001), and were lower on day 30 compared to day 1, and significantly lower on day 90 compared to all other times (Supplementary Table 13, Supplementary Fig. 9). CR efficiencies also changed significant through time and were lower on day 1 compared to day 7 and day 30 (F2, 20 = 9.16, p <0.001) (Supplementary Table 14, Supplementary Fig. 10).

Discussion

We found a strong combined effect of elevated salinity and nutrient enrichment on the metabolic function of freshwater benthic bacterial communities. Community level physiological profiles differed, and total mean and maximum carbon metabolic rates were lower in the combined stressor treatment compared to either stressor in isolation and compared to ambient conditions, with carbohydrate, carboxylic acid and amino acid metabolism most affected. Contrary to our predictions, the magnitude of these stress-induced changes in metabolic function did not recover through time. Together these results show that the effects of multiple stressors on bacterial community metabolism were stronger than individual stressor effects and could not be predicted from examining effects of each stressor in isolation. Contrary to our predictions we did not see strong effects of stressors on bacterial community taxonomic structure, although there was an initial trend for decreased bacterial diversity under the combined stressor treatment, and some effects of treatment on the temporal changes in concentration of green algae throughout the experiment. This suggests the metabolic functional responses of freshwater bacterial communities may be more sensitive to environmental stressors than bacterial community taxonomic structure and other broad compositional metrics (e.g. concentration of groups of phototrophic organisms), emphasising the importance of direct functional measures.

The magnitude of metabolic functional changes in benthic bacterial communities was greatest under combined nutrient enriched and elevated salinity conditions. Bacterial community metabolic rates increased with increased nutrient concentrations, although this was only evident after 30 days. This supports the general finding that nutrient enrichment can enhance bacterial community metabolic functional rates by overcoming resource limitations on microbial activity49,53,54, but contrasts with the finding that nutrient enrichment causes rapid, short-lived effects on aquatic bacterial community functions which typically recover over time48. This metabolic effect coincided with green algae concentrations also being significantly higher in the nutrient enriched treatment compared to elevated salinity and combined stressors, suggesting broad measures of taxonomic structure (i.e. concentration of groups of phototrophic organisms) may correlate with metabolic function under some stressor scenarios. There was a trend of decreased metabolic rates under elevated salinity, which may have been due to intracellular osmotic stress, although this effect was not statistically significant. Metabolic rates decreased faster (after one day) and to a greater magnitude under the combined stressor treatment compared to under either stressor individually. This supports the growing evidence that multiple stressors often have strong combined effects in aquatic ecosystems19,57,58,59,60 and extends this trend to the metabolic function of freshwater benthic microbial communities. Under combined stressors, community level physiological profiles also shifted compared to all other treatments. This suggests that when the community was exposed to the two stressors with contrasting mechanisms of interference, the cumulative stress induced a major shift in the relative use of different carbon sources which did not occur under each stressor individually. This physiological shift in metabolic profile provides a potential mechanistic underpinning for the synergistic stressor interaction.

Changes in metabolic rates under the stressor treatments were carbon group specific. Under conditions of combined elevated salinity and nutrient enrichment, rates of metabolism for carbohydrates, carboxylic acids and amino acids decreased significantly, while no significant differences were observed for polymers, phenols or amines. This pattern aligns with established findings that carbohydrate, carboxylic acid and amino acid metabolism in aquatic biofilm communities tend to be more sensitive to environmental stressors compared to the metabolism of polymers, phenols and amines69,70. One explanation for this heightened sensitivity lies in the composition of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) within the biofilm matrix, which is predominantly made up of polysaccharides, proteins and carboxylic acids71. Consequently, biofilms are typically rich in extracellular enzymes that target these EPS compounds, including carbohydrates, amino acids and carboxylic acids71. Under conditions of combined elevated salinity and nutrient enrichment, the production of these extracellular enzymes may have diminished as microbial energy resources were redirected towards mechanisms of stress tolerance, potentially driving the observed significant decreases in the metabolism of these carbon groups.

Rates of microbial carbon metabolism and the carbon use profiles of microbial communities can be key determinants of decomposition rates and total organic carbon release for higher organisms. While these processes are well studied in terrestrial soils72,73, they are increasingly recognised in freshwater systems74,75. These results imply that under multiple stressor scenarios carbon metabolism profiles will shift and overall rates of organic carbon metabolism, including organic matter decomposition and organic carbon release, are likely to decrease. However, while our study provides insights into the initial and intermediate responses of bacterial community metabolic functions, these functions were not measured at the 90-day time point, which restricts our ability to fully assess long-term functional dynamics. Future studies would benefit from quantifying the carbon metabolic profiles and rates of benthic bacterial communities across longer time periods to capture comprehensive temporal trends.

The community level metabolic changes observed under nutrient enrichment and salinisation were not associated with changes in overall community productivity as quantified by total biofilm biomass, photosynthetic efficiency, community respiration, net primary productivity and gross primary productivity. This suggests the stressors interfered with the metabolic physiology of the community without impairing overall productivity. This stability in productivity may be explained by niche partitioning, a compensatory mechanism where the decreased productivity of sensitive organisms is balanced by the increased productivity of resistant organisms76,77,78,79. For example, the decreased metabolism of organic carbons observed under salinisation may have been balanced by an increase in the activity of autotrophs and/or organisms with a non-organic carbon metabolic preference resulting in no net change to overall community productivity. However, total biofilm biomass, as measured by chlorophyll a concentration, decreased throughout the experimental period and was significantly lower on day 90 compared to all other time points for all treatments. Similarly, the efficiency of community respiration also significantly decreased through time. This decrease in total biofilm biomass coincided with a significant decrease in the oxygen concentration in pond water through time, which turned largely anoxic by day 90. Therefore, it is possible that environmental changes, such as oxygen depletion, that impacted all treatment ponds equally may have masked potential treatment effects on biofilm functional metrics such as biomass and respiration rates.

Contrary to our expectations, stressors had no impact on community structural metrics, including bacterial ASV abundance, diversity, structure and composition, although a trend was observed for decreased bacterial diversity under the combined stressor treatment. Several possible explanations could account for the unexpected resistance (i.e. no observed change) of bacterial community structure to all stressor regimes. First, once established, biofilms can exhibit strong structural stability and resistance to environmental disturbances80. The 30-day development period in ambient conditions, prior to the application of treatments, may have allowed biofilms to develop a highly resistant protective extracellular matrix enabling structural stability as has been observed for biofilms under various extreme stressor scenarios81. The procedure of gently shaking the tiles to remove sediment and loosely attached organisms may have had some disturbance on organisms attached to the outer layer of the biofilm structure. Bacteria that had adhered to the outer layers of the biofilm and were in direct or close contact with the water-column stressors may have shown the strongest taxonomic changes; however, these loosely attached microorganisms would have been more likely representative of assemblages in the water column, rather than the benthic microbial community, which was the target in our study and for which we did observe functional effects of treatments. Second, dormancy, a common microbial response to environmental stressors, might have resulted in treatment effects being masked by the retention of DNA from dormant or dead cells in the extracellular biofilm matrix14,82. Finally, the four independent ambient ponds in which biofilms developed were established ten years ago, which may have resulted in different ecological trajectories that may have introduced variation in community assembly and bacterial community structure on the tiles at the start of the experiment. These differences in initial community assembly may have introduced variability in community responses to stressors, and this variability may have decreased statistical power to detect treatment effects (if any). Regardless of the cause of the lack of treatment effects observed in the bacterial taxonomic structure, our results indicate that bacterial community structure based on DNA amplicon sequencing is not always a strong indicator of freshwater community metabolic responses to environmental stressors. These findings challenge the notion that DNA-based measures of bacterial community taxonomic structure are key indicators of functional change and instead supports literature suggesting that microbial structure and functional responses to stressors often occur independently19,57,58,59,60.

This study demonstrates that the effects of two key global freshwater stressors, nutrient enrichment and salinisation, on benthic bacterial community metabolic function were stronger where stressors were combined compared to individual effects, and that these functional effects occurred largely independently of changes in bacterial community taxonomic structure. These results suggest that as freshwater stressors increasingly co-occur under global change scenarios, the metabolic profiles of benthic bacterial communities will likely shift and overall rates of organic carbon metabolism will decrease, potentially affecting organic matter decomposition, organic carbon release and the freshwater carbon cycle. In addition, these results suggest that future research on freshwater benthic microbial communities and other similarly resistant communities (e.g. environmental biofilms) should prioritise direct measurements of microbial community functions when assessing microbial responses to environmental stressors, rather than inferring functional change solely from shifts in bacterial community taxonomic structure.

Methods

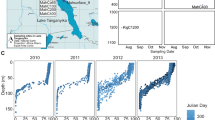

Field ponds

The experiment was done in an outdoor field in Toledo, Spain, which contained 32 open freshwater experimental ponds (hereafter ‘ponds’). The ponds were 1000 L polyethylene tubs (cattle tanks), each 0.70 m deep and 1.85 m diameter. The ponds were setup in 2014 by adding 100 kg of locally collected topsoil and filled with locally collected freshwater. The ponds were subsequently colonized by various organisms from bacteria to small vertebrates, resulting in naturally established freshwater communities that resemble natural small freshwater ponds64. The water column is dominated by alternating cycles of phytoplankton and zooplankton while the benthos contains diverse assemblages of aquatic macrophytes and invertebrates (e.g. beetles, dragonflies, mosquito larvae)65.

Experimental design

To test the effects of salinisation and nutrient enrichment on freshwater benthic microbial communities, 16 ponds (hereafter ‘treatment ponds’) were randomly selected and allocated to each of four treatments (four ponds per treatment, spatially interspersed): elevated salinity (S), elevated nutrients (N), elevated salinity and nutrients (combined stressors; SN) and undisturbed (i.e. ambient; A). Salt and nutrients were added to ponds by dissolving 15 g NaCl/L as commercially available rock salt (sodium chloride, NaCl), 10 mg N/L (as sodium nitrate; NaNO3; GPR RECTAPUR®) and 1 mg of P/L (as sodium dihydrogen phosphate; NaH2PO4; GPR RECTAPUR®) in a 20 L bucket with water from each pond by stirring, and then adding the dissolved salts and/or nutrients back into the pond.

The salinity and nutrient levels in this experiment were selected to maintain ecological relevance to the key global freshwater threats of salinisation and nutrient enrichment while reaching thresholds to provide insights into nutrient-salinity interactions in aquatic ecosystems. 15 g NaCl/L reflects the upper limit of concentrations observed in freshwater ponds undergoing significant salinisation, for example, following road de-icing using salt83. Previous research has shown that salinities between 4 and 10 g/L can negatively impact freshwater micro-algal biomass84,85, and short-term exposure to salinities of 15 g/L have had significant effects on benthic freshwater biofilm photosynthetic efficiency, nutrient uptake, and diatom biodiversity42,86, indicating potential thresholds for freshwater microbial community salinity responses. We used a 10x nutrient addition, corresponding to an increase of +10 mg N/L and +1 mg P/L, to simulate conditions typical of nutrient-enriched environments. Nitrate concentration of 10 mg/L reflects the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s threshold for nitrate in freshwater due to risks of eutrophication and human health impacts87. A manipulation of this magnitude has been shown to lead to eutrophic conditions in similarly sized pond mesocosms while maintaining a 10:1 N:P ratios88. This magnitude of nutrient enrichment has also been shown to significantly affect the photosynthetic function and phosphorous uptake efficiency of freshwater benthic microbial communities32, indicating potential thresholds for freshwater microbial community nutrient enrichment responses.

A total of 268 ceramic tiles (2 × 2 cm) were randomly deployed across four additional ponds under ambient conditions (hereafter ‘development ponds’) and left to develop biofilms for 30 days (Fig. 6). The 30 day development period was selected to reflect the timeframes for pond biofilms to reach the ‘development phase’ of maturation, where organisms are imbedded in an adherent extra-cellular matrix and a relatively taxonomically stable prokaryotic and eukaryotic community has developed89. Tiles were placed ~2–5 cm apart on plastic trays sitting on the sediment at the bottom of each pond. To assess the variability in abiotic and biotic conditions among the four ambient biofilm development ponds, oxygen concentration, conductivity, pH, chlorophyll a concentration, nitrate concentration and phosphate concentrations were measured in each pond on the day tiles with biofilms were moved into treatment ponds (described below). Water conditions across the four biofilm development ponds were basic (pH ranging from 9.7 to 10.3), oxygen depleted (ranging from 0.0–0.78 mg/L) and nitrogen limited (nitrite concentrations <0.025 mg/L, nitrate concentrations <0.01 mg/L). Other abiotic and biotic conditions varied among the development ponds, with phosphate concentrations ranging from 0.08 to 6.00 mg/L, chlorophyll a concentration ranging from 86.81 to 3024 µg/mL, and conductivity ranging from 2.820 to 5.920 mS/cm (Supplementary Table 1). After 30 days of biofilm development, one tile was removed from each development pond for baseline sampling of bacterial community structure (sampling methods described below), while all other tiles were randomly moved into a treatment pond (i.e. A, S, N or SN) (Fig. 6). Each treatment pond received 16 tiles. Baseline bacterial community structure data was not included in statistical analyses as this treatment was not included in our hypothesis testing, however, this data is included in Supplementary Fig. 4 to illustrate initial variability among communities.

Pond conditions

To test for the effects of treatments and time on the abiotic and biotic characteristics of water in treatment ponds, on days 1, 30 and 90 water oxygen concentration, conductivity and pH were measured using a HQ40d Multi-Metre (Hach, Australia) and IntelliCAL® LDO101 luminescent/optical dissolved oxygen probe, IntelliCAL ® CDC401 conductivity probe and IntelliCAL ® PHC101 pH probe directly into pond water. Chlorophyll a concentration in water was also quantified using an AquaFluor (Turner Designs) portable fluorometer64. To test whether the added nutrients had been consumed from the water column within the 30 days between nutrient addition and biofilms being moved into the treatment ponds, on day 1 when biofilms were moved into treatment ponds, water samples were collected in 100 mL plastic jars to quantify concentration of nitrite, nitrate and phosphate using UV-VIS spectrophotometry64.

In this experiment elevated salinity acted as a press stressor90, with conductivity remaining significantly higher in the elevated salinity and combined stressor treated ponds compared to nutrient enriched and ambient ponds throughout the duration of the experiment (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 2). Nutrient enrichment acted as a pulse stressor90, with nitrite concentrations returning to <0.025 mg/L and nitrate concentrations returning to <0.1 mg/L in all ponds within 30 days of nutrient addition (Supplementary Tables 3, 4, Supplementary Fig. 3).

Biofilm sampling

After 1, 7 and 30 days of being moved into a treatment pond, three tiles from each pond were randomly selected and destructively sampled (Fig. 6). On day 1, tiles were also sampled from the development ponds to obtain baseline metrics. In each instance, tiles were shaken underwater for 30 s to remove sediment and any loosely attached organisms. One tile was used for Community Level Physiological Profiling (CLPP), one tile was used for analyses of community respiration (CR), net primary productivity (NPP), gross primary productivity (GPP), concentration of groups of phototrophic organisms and photosynthetic yield, and the final tile was used to quantify bacterial community structure (details below). After 90 days we quantified the concentration of groups of phototrophic organisms, photosynthetic yield and bacterial community structure to determine long-term stressor effects (Fig. 6). CLPPs, CR, NPP and GPP were not quantified at 90 days because pond water had turned anoxic in treatment ponds (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 2). Given the anoxic conditions it was not possible to detect changes in oxygen concentrations during in situ incubations to quantify CR and NPP, nor was it possible to incubate EcoPlates in conditions similar enough to the field (i.e. anaerobically).

Community structure

To determine the bacterial structure of biofilms after exposure to different stressors and their combinations, the entire surface of the tile was swabbed for 30 s using a sterile cotton swab and placed into a sterile cryotube. Samples were frozen at –20 oC in a portable freezer for 24 h until reaching the laboratory, where samples were stored at –80 oC until DNA extraction.

DNA extraction, sequencing and bioinformatics

DNA was extracted from swabs using the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro DNA kit (QIAGEN) as per manufacturer instructions. PCR was performed on DNA to amplify the V3 - V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene using the 341 - forward primer (CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG) and the 805 - reverse primer (GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC)91. PCR conditions involved a pre-heating step to 95 °C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 1 min and 73 °C for 30 s which is adapted based on the protocol specified in the Illumina library preparation workflow. Both positive (with known DNA sequence) and negative controls (nuclease-free water, control swabs) were used. Some replicates did not amplify so we proceeded with three samples per treatment and time point for sequencing for most Treatment*Time combinations, except for the SN treatment on day 7 and 30 where four samples were sequenced. Quality control and library preparation using two-step barcoding and paired-end amplicon sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq (v3) sequencer at the Ramaciotti Centre for Genomics with a 300-bp sequence length. Sequencing was performed in a single flow cell.

Primers and barcodes were removed from the raw sequences which were then processed through the DADA2 package (v 1.30.0) within the Bioconductor software environment in R (v 4.3.2)92. Briefly, reads were initially quality filtered and any base pairs with a mean Q score < 20 were dropped, resulting in a final truncation at 290 bp for forward reads and 250 bp for reverse reads93. Maximum error rates were calculated independently on the forward and reverse reads and the DADA2 denoising algorithm was used to detect rare amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) and chimeric sequences. After denoising, all paired reads were merged and an ASV abundance table was constructed. Taxonomic assignment was initially performed using the SILVA reference database (v 138.1)94 to detect chloroplast, mitochondrial and archaeal sequences. A second round of taxonomic assignment was performed using the Genome Taxonomy Database (v 202)95.

Total abundance of the 16S rRNA gene was quantified for each sample by qPCR using the primers 341 F/805 R. Gene amplification and analysis were performed using the QuantStudio 3 thermocycler (Thermo Fisher with PrimeTime® Gene Expression Master Mix, Integrated DNA Technologies) and associated software. The reaction conditions for amplification of DNA were 56 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. Relative ASV abundances were corrected to absolute abundances using 16S gene copies obtained from the qPCR96. ASVs assigned to the kingdom ‘Archaea’ ( <1% total ASVs), unassigned ASVs at the kingdom level ( <0.01% total ASVs), chloroplasts ( <1% total ASVs) and chimeras ( <1% total ASVs) were then removed. Singletons and ASVs with abundances <0.001% of the total ASV count, which was selected as a cut-off point by inspecting ASV abundance plots, were also removed, reducing ASV count from ~11,000 to ~2000. Species accumulation (rarefaction) curves were generated using the ‘specaccum‘ function in the vegan package in R97 with the ‘random’ method, which randomises the order of samples to account for sample-size variability (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Concentration of groups of phototrophic organisms

To determine the concentrations of groups of phototrophic organisms in the benthic communities after exposure to stressors and their combination, tiles (n = 4 per treatment and time-point) were removed from ponds (one tile per pond) and concentrations of diatoms, cyanobacteria and green algae in each tile were quantified based on pigment fluorescence using a BenthoTorch fluorometer (BBE, Moldaenke)98. We performed one reading per tile. The BenthoTorch fluorometer distinguishes between different phototrophic groups by sequentially exciting microalgal accessory pigments, which have unique excitation profiles, using multiple light-emitting diodes and measuring the fluorescence emitted at 680 nm. The resulting fluorescence intensity allow for the identification and quantification of major phototrophic groups, including green algae, diatoms, and cyanobacteria98,99.

Community level physiological profiling

To determine the Community Level Physiological Profiles (CLPPs) of bacterial communities after exposure to different stressors and their combinations, tiles (n = 4 per treatment and time-point, each from a different pond) were placed into individual watertight jars filled with water from their source pond for metabolic analyses. Jars containing the tiles were placed in an insulated cooler to minimise changes in water temperature during transport to the MNCN-CSIC laboratory facilities in Madrid. Samples were processed within three hours of arrival. Tiles were removed from their jars and gently rinsed in Phosphate Buffered Saline solution (PBS). Biofilms were then removed from the tiles with a cell-scraper and suspended in 5 mL of PBS. The absorbance at an optical density of 590 nm (OD590) of the suspension was measured with a spectrophotometer and diluted to ~0.05 to minimise effects of initial inoculum cell density on metabolic rates100,101. 150 \(\mu\)L of cell suspension was then added to each well of a 96-well Biolog EcoPlateTM (Biolog Inc. Hayward, CA, USA; hereafter EcoPlate), with each plate corresponding to one tile (i.e. 16 plates per sampling time-point, with n = 4 plates per treatment at each time-point). Each EcoPlate consisted of three replicates of each of 31 sole carbon sources and three replicate water blanks as negative controls (i.e. 96 wells per plate) together with the redox dye tetrazolium violet. The 31 carbon sources were grouped into six carbon-type groups: carbohydrates, carboxylic acids, amino acids, phenols, polymers and amines. Formazan is produced as the carbon source is oxidized and the colour change through time can be quantified spectrophotometrically. The baseline OD590 of each well was measured using a microplate spectrophotometer and repeated every 24 h for 96 h. Plates were incubated in the dark at 25 oC, which is representative of the water temperature in the ponds during the incubation period (June-July 5-year median: 24.63 oC, mean: 25.36 oC ± SE 0.92 °C, n = 32). As for all incubation methods, the microbial communities in the wells of EcoPlates can drift away from their natural field structure owing to culture bias, i.e. the change in community owing to the selective pressures of the incubation period which differ from their natural environment102. Nevertheless, as we expected any potential incubation-related community drift to have affected all treatments equally, treatment effects detected using EcoPlates were considered valid indicators of comparative functional differences in microbial communities, as is widely accepted in the literature73,103,104,105.

CLPP data processing

The OD590 values for each well in each plate and for each reading/incubation time-point (0 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 96 h) were corrected by subtracting the mean OD590 value of the water negative-control wells in each plate/reading time-point (Supplementary Figs. 6, 7). Any negative OD590 values after negative-control correction were adjusted to zero. We then calculated the mean OD590 values of the three technical replicates for each carbon source in each plate, plotted these values across all reading time-points and calculated the mean and maximum slope values for each curve. Mean and maximum slope values represent the mean and maximum metabolic rates for each carbon source and these values were used in subsequent univariate and multivariate analyses106. Mean and maximum slopes are kinetic parameters that capture the rate of carbon metabolism rather than single-point measures like average well colour development (AWCD) or substrate richness. Kinetic parameters are generally more sensitive indicators of metabolic function compared to single-point measures and are less sensitive to biases introduced by the timing of incubations and differences in initial inoculum densities105. For univariate analyses, the mean and maximum slope values for each carbon source were treated as replicates (i.e. 31 values per plate/replicate tile) and ‘Pond’ was included as a random effect to account for non-independence (as the samples incubated on each plate came from individual tiles, each from a different pond, but ponds were sampled repeatedly through time). In addition, we calculated mean and maximum slope values for each of the six carbon groups by pooling the data by carbon type for univariate analyses for each of these carbon type groupings. All these univariate metrics were analysed using linear mixed effects models (details on models fitted below). To test hypotheses about the effects of treatments and time on multivariate carbon metabolic profiles permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) models were run on Euclidean distances calculated on maximum metabolic rate of each of the 31 carbon sources (details on models fitted below).

Productivity, chlorophyll a and photosynthesis

To test hypotheses about the effects of treatment and time on Community Respiration (CR), Net Primary Productivity (NPP) and Gross Primary Productivity (GPP), microbial communities on tiles were removed from their ponds and placed in watertight jars containing 150 mL of water from their source pond for measures of oxygen production and consumption. Pond water was filtered using 20 μm filters to minimise the contribution of larger water-borne photosynthetic organisms (e.g., phytoplankton) to oxygen production and consumption. Smaller organisms (e.g. waterborne bacteria) may have contributed to these oxygen fluxes and therefore these data represent the oxygen production and consumption from both benthic and planktonic bacteria, although the contribution of the latter would have been much lower than the benthic component given the density of planktonic organisms in the water column is much lower than the density of organisms in biofilms107. Dissolved oxygen concentration was measured in each jar containing each tile pre- and post- two-hour incubations in the dark, and then pre- and post- two-hour incubations in the light using a HQ40d Multi-Metre (Hach, Australia) and IntelliCAL ® LDO101 luminescent/optical dissolved oxygen probe.

CR rates were calculated by subtracting the oxygen concentration at the end of the dark incubation period from the oxygen concentration at the beginning of the dark incubation period. NPP rates were calculated by subtracting the oxygen concentration at the end of the light incubation period from the oxygen concentration at the beginning of the light incubation period. The changes in oxygen concentrations (in mg/L) were converted to micromoles per litre (µM/L) using the molecular weight of O2 (32 g/mol). The CR and NPP values were adjusted to account for the surface area of the tiles used in the experiment, which was 0.0016 m². Finally, the rates were expressed per hour by dividing the adjusted values by the incubation time of two hours. GPP rates were calculated by subtracting CR from NPP. NPP was calculated as the change in dissolved oxygen concentration per hour of light incubation; CR was calculated as the change in dissolved oxygen concentration per hour of dark incubation. GPP was calculated as NPP subtracting CR108,109. In addition, to calculate efficiencies in each of the CR, NPP and GPP values, raw CR, NPP and GPP values for each sample were divided by the total chlorophyll a concentration of that sample.

After oxygen incubation, tiles were removed from their incubation jars and placed under individual black plastic covers for five minutes of dark adaptation. Maximum photosynthetic quantum yields were then measured using a Pulse Amplitude Modulated (PAM) fluorometer (WALZ, Germany)32. Total chlorophyll a concentrations were calculated as the sum of the concentrations for green algae, diatoms and cyanobacteria and were used as a proxy for biofilm biomass110,111. For each of these analyses measurements were performed using the whole tile community assemblage that remained adherent to the tile after 30 s of shaking in the pond water (i.e. an adherent mixed species biofilm, sensu107).

Statistical analyses

To test hypotheses about the effects of Treatment (fixed, four levels: A, S, N, SN) and Time (fixed, crossed, 4 levels: 1, 7, 30, 90 days) on benthic microbial community structure, Shannon’s diversity index (calculated in the R vegan package) was analysed via linear mixed effects models using the lmer function from the “lme4” package in R112. ‘Pond’ was a random factor nested in Treatment, but crossed with Time. Beta-diversity analyses were done on Bray–Curtis dissimilarities among sample-pairs, calculated on square-root transformed, absolute ASV abundances, as well as on Jaccard dissimilarities among sample-pairs (presence-absence data; i.e. composition only). Dissimilarities were analysed using permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) fitting a model with the three factors stated above. Non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (nMDS) ordination was used to visualise multivariate patterns of community structure.

To test for effects of Treatment and Time on microbial community function, maximum metabolic rates, mean metabolic rates, photosynthetic yield, CR rates, NPP rates, GPP rates, and biomass were analysed by fitting univariate linear mixed effects models as described above, but with three levels for Time: 1, 7 and 30 days. We also analysed the multivariate metabolic carbon profiles (i.e. each of the 31 carbon sources as response variables) via PERMANOVA, as described above, on Euclidean distances calculated for each sample pair. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to visualise multivariate patterns of metabolic carbon profiles113.

For all univariate models, p values were calculated using the F-statistic with Satterthwaite degrees of freedom in the ‘Anova’ function (type 2) of the ‘car’ package in R114 and, where appropriate (significant Treatment x Time interactions or, where interactions were absent, significant main effect of Treatment or Time), post-hoc tests were conducted using the emmeans package in R115. Plots of residuals vs fitted values were inspected to check model assumptions and model fit. For multivariate analyses, models were run using PERMANOVA in PRIMER v6 (PRIMER-E, UK). Multivariate dispersions were checked for homogeneity by analysing distances from centroid data using Permdisp in PRIMER.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the Dryad Digital Repository at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.sxksn03cg.

References

Folke, C. et al. Regime shifts, resilience, and biodiversity in ecosystem management. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35, 557–581 (2004).

Hector, A. & Bagchi, R. Biodiversity and ecosystem multifunctionality. Nature 448, 188–190 (2007).

Tilman, D. & Downing, J. A. Biodiversity and stability in grasslands. Nature 367, 363–365 (1994).

Cavicchioli, R. et al. Scientists’ warning to humanity: microorganisms and climate change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 569–586 (2019).

Falkowski, P. G., Fenchel, T. & Delong, E. F. The microbial engines that drive earth’s biogeochemical cycles. Science 320, 1034–1039 (2008).

Graham, E. B. et al. Microbes as engines of ecosystem function: When does community structure enhance predictions of ecosystem processes?. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1–10 (2016).

Reed, H. E. & Martiny, J. B. Microbial composition affects the functioning of estuarine sediments. ISME J. 7, 868–879 (2013).

Philippot, L., Griffiths, B. S. & Langenheder, S. Microbial community resilience across ecosystems and multiple disturbances. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 85, 2–24 (2021).

Grimm, V. & Wissel, C. Babel, or the ecological stability discussions: An inventory and analysis of terminology and a guide for avoiding confusion. Oecologia 109, 323–334 (1997).

Mikola, J., Setälä, H. & Setala, H. Relating species diversity to ecosystem functioning: Mechanistic backgrounds and experimental approach with a decomposer food web. Oikos 83, 180 (1998).

Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. Soil microbial communities drive the resistance of ecosystem multifunctionality to global change in drylands across the globe. Ecol. Lett. 20, 1295–1305 (2017).

Glassman, S. I. et al. Decomposition responses to climate depend on microbial community composition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 11994–11999 (2018).

Agrawal, A. A. Phenotypic plasticity in the interactions and evolution of species. Science 294, 321–326 (2001).

Kearns, P. J. et al. Nutrient enrichment induces dormancy and decreases diversity of active bacteria in salt marsh sediments. Nat. Commun. 7, 12881 (2016).

Moya, A. & Ferrer, M. Functional redundancy-induced stability of gut microbiota subjected to disturbance. Trends Microbiol. 24, 402–413 (2016).

Tian, L. et al. Deciphering functional redundancy in the human microbiome. Nat. Commun. 11, 6217 (2020).

Lozupone, C. A., Stombaugh, J. I., Gordon, J. I., Jansson, J. K. & Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 489, 220–230 (2012).

MetaHIT Consortium et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 464, 59–65 (2010).

Birk, S. et al. Impacts of multiple stressors on freshwater biota across spatial scales and ecosystems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1060–1068 (2020).

Dal Bello, M., Rindi, L. & Benedetti-Cecchi, L. Legacy effects and memory loss: how contingencies moderate the response of rocky intertidal biofilms to present and past extreme events. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 3259–3268 (2017).

Shade, A. et al. Fundamentals of microbial community resistance and resilience. Front. Microbiol. 3, 1–19 (2012).

Jurburg, S. D., Blowes, S. A., Shade, A., Eisenhauer, N. & Chase, J. M. Synthesis of recovery patterns in microbial communities across environments. Microbiome 12, 79 (2024).

Gonzalez-Silva, B. M., Jonassen, K. R., Bakke, I., Østgaard, K. & Vadstein, O. Understanding structure/function relationships in nitrifying microbial communities after cross-transfer between freshwater and seawater. Sci. Rep. 11, 2979 (2021).

Berga, M., Székely, A. J. & Langenheder, S. Effects of disturbance intensity and frequency on bacterial community composition and function. PLoS ONE 7, e36959 (2012).

Landuyt, D. et al. An ecosystem service approach to support integrated pond management: A case study using Bayesian belief networks – Highlighting opportunities and risks. J. Environ. Manag. 145, 79–87 (2014).

Sterner, R. W. et al. Ecosystem services of Earth’s largest freshwater lakes. Ecosyst. Serv. 41, 101046 (2020).

Piggott, J. J., Niyogi, D. K., Townsend, C. R. & Matthaei, C. D. Multiple stressors and stream ecosystem functioning: climate warming and agricultural stressors interact to affect processing of organic matter. J. Appl. Ecol. 52, 1126–1134 (2015).

Matthaei, C. D., Piggott, J. J. & Townsend, C. R. Multiple stressors in agricultural streams: interactions among sediment addition, nutrient enrichment and water abstraction: Sediment, nutrients & water abstraction. J. Appl. Ecol. 47, 639–649 (2010).

Lange, K., Liess, A., Piggott, J. J., Townsend, C. R. & Matthaei, C. D. Light, nutrients and grazing interact to determine stream diatom community composition and functional group structure: Diatom responses to light, nutrients and grazing. Freshw. Biol. 56, 264–278 (2011).

Piggott, J. J., Salis, R. K., Lear, G., Townsend, C. R. & Matthaei, C. D. Climate warming and agricultural stressors interact to determine stream periphyton community composition. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 206–222 (2015).

Beermann, A. J. et al. Multiple-stressor effects on stream macroinvertebrate communities: A mesocosm experiment manipulating salinity, fine sediment and flow velocity. Sci. Total Environ. 610–611, 961–971 (2018).

Moyano Salcedo, A. J. et al. What happens when salinization meets eutrophication? A test using stream microcosms. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 168824 (2024).

Ren, L. et al. Warming and nutrient enrichment in combination increase stochasticity and beta diversity of bacterioplankton assemblages across freshwater mesocosms. ISME J. 11, 613–625 (2017).

Romero, F., Acuña, V. & Sabater, S. Multiple stressors determine community structure and estimated function of river biofilm bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 86, e00291–20 (2020).

Graça, D., Arias-Real, R., Fernandes, I., Cássio, F. & Pascoal, C. Fungal identity mediates the impacts of multiple stressors on freshwater ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 937, 173466 (2024).

Romero, F., Acuña, V., Font, C., Freixa, A. & Sabater, S. Effects of multiple stressors on river biofilms depend on the time scale. Sci. Rep. 9, 15810 (2019).

Lind, L. et al. Salty fertile lakes: how salinization and eutrophication alter the structure of freshwater communities. Ecosphere 9, e02383 (2018).

Cunillera-Montcusí, D. et al. Freshwater salinisation: a research agenda for a saltier world. Trends Ecol. Evol. 37, 440–453 (2022).

Sagova-Mareckova, M. et al. Expanding ecological assessment by integrating microorganisms into routine freshwater biomonitoring. Water Res. 191, 116767 (2021).

Berga, M., Zha, Y., Székely, A. J. & Langenheder, S. Functional and compositional stability of bacterial metacommunities in response to salinity changes. Front. Microbiol. 8, 948 (2017).

Sivakumar, K. et al. Salinity-mediated increment in sulfate reduction, biofilm formation, and quorum sensing: A potential connection between quorum sensing and sulfate reduction?. Front. Microbiol. 10, 188 (2019).

Vendrell-Puigmitja, L. et al. Hypersaline mining effluents affect the structure and function of stream biofilm. Sci. Total Environ. 843, 156966 (2022).

Zhang, L., Gao, G., Tang, X. & Shao, K. Impacts of different salinities on bacterial biofilm communities in fresh water. Can. J. Microbiol. 60, 319–326 (2014).

Berger, E., Frör, O. & Schäfer, R. B. Salinity impacts on river ecosystem processes: a critical mini-review. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 374, 20180010 (2019).

Canhoto, C., Oliveira, R., Martínez, A. & Gonçalves, A. L. Pulsed vs. chronic salinization effects on microbial-mediated leaf litter decomposition in fresh waters. Hydrobiologia 850, 4547–4556 (2022).

Martínez, A., Gonçalves, A. L. & Canhoto, C. Salinization effects on stream biofilm functioning. Hydrobiologia 847, 1453–1459 (2020).

Koch, R., Kerling, D. & O’Brien, J. M. Effects of chronic elevated nitrate concentrations on the structure and function of river biofilms. Freshw. Biol. 63, 1199–1210 (2018).

Rindi, L. & Benedetti-Cecchi, L. Short-term stability of rocky intertidal biofilm to nitrogen and phosphorus pulses. Mar. Environ. Res. 183, 105795 (2023).

Van Horn, D., Sinsabaugh, R., Takacs-Vesbach, C., Mitchell, K. & Dahm, C. Response of heterotrophic stream biofilm communities to a gradient of resources. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 64, 149–161 (2011).

Leff, J. W. et al. Consistent responses of soil microbial communities to elevated nutrient inputs in grasslands across the globe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 10967–10972 (2015).

Zhu, W. et al. Effects of nutrient levels on microbial diversity in sediments of a eutrophic shallow lake. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, 909983 (2022).

Geng, M. et al. Eutrophication causes microbial community homogenization via modulating generalist species. Water Res. 210, 118003 (2022).

Ferreira, V. et al. A meta-analysis of the effects of nutrient enrichment on litter decomposition in streams. Biol. Rev. 90, 669–688 (2015).

Manning, D. W. P., Rosemond, A. D., Gulis, V., Benstead, J. P. & Kominoski, J. S. Nutrients and temperature additively increase stream microbial respiration. Glob. Change Biol. 24, e233–e247 (2018).

Rillig, M. C. et al. Increasing the number of stressors reduces soil ecosystem services worldwide. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 478–483 (2023).

Suleiman, M., Daugaard, U., Choffat, Y., Zheng, X. & Petchey, O. L. Predicting the effects of multiple global change drivers on microbial communities remains challenging. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 5575–5586 (2022).

Griffen, B., Belgrad, B., Cannizzo, Z., Knotts, E. & Hancock, E. Rethinking our approach to multiple stressor studies in marine environments. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 543, 273–281 (2016).

O’Brien, A. L., Dafforn, K. A., Chariton, A. A., Johnston, E. L. & Mayer-Pinto, M. After decades of stressor research in urban estuarine ecosystems the focus is still on single stressors: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 684, 753–764 (2019).

Perujo, N. et al. A guideline to frame stressor effects in freshwater ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 777, 146112 (2021).

White, L., O’Connor, N. E., Gilson, A. & Donohue, I. Species contributions to ecosystem stability change with disturbance type. Oikos e10077 (2024).

Piggott, J. J., Townsend, C. R. & Matthaei, C. D. Reconceptualizing synergism and antagonism among multiple stressors. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1538–1547 (2015).

Ferreira, V. & Chauvet, E. Synergistic effects of water temperature and dissolved nutrients on litter decomposition and associated fungi. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 551–564 (2011).

Burdon, F. J. et al. Stream microbial communities and ecosystem functioning show complex responses to multiple stressors in wastewater. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 6363–6382 (2020).

Nava, V., Matias, M. G., Castillo-Escrivà, A., Messyasz, B. & Leoni, B. Microalgae colonization of different microplastic polymers in experimental mesocosms across an environmental gradient. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 1402–1413 (2022).

Pereira, C. L., Gilbert, M. T. P., Araújo, M. B. & Matias, M. G. Fine-tuning biodiversity assessments: A framework to pair eDNA metabarcoding and morphological approaches. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 2397–2409 (2021).

Battin, T. J., Kaplan, L. A., Denis Newbold, J. & Hansen, C. M. E. Contributions of microbial biofilms to ecosystem processes in stream mesocosms. Nature 426, 439–442 (2003).

Battin, T. J., Besemer, K., Bengtsson, M. M., Romani, A. M. & Packmann, A. I. The ecology and biogeochemistry of stream biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 251–263 (2016).

Peter, H. et al. Multifunctionality and Diversity in Bacterial Biofilms. PLoS ONE 6, e23225 (2011).

Németh, I., Molnár, S., Vaszita, E. & Molnár, M. The Biolog EcoPlateTM Technique for Assessing the Effect of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles on Freshwater Microbial Communities. Nanomaterials 11, 1777 (2021).

González, M.-L., Fuentes, M. E., Molina, V. & Quiñones, R. A. Effects of ethoxyquin on metabolism and composition of active marine microbial communities. Aquaculture 569, 739345 (2023).

Flemming, H.-C. & Wingender, J. The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 623–633 (2010).

Tao, F. et al. Microbial carbon use efficiency promotes global soil carbon storage. Nature 618, 981–985 (2023).

Urbaniak, M., Mierzejewska-Sinner, E., Bednarek, A., Krauze, K. & Włodarczyk-Marciniak, R. Microbial response to Nature-Based Solutions in urban soils: A comprehensive analysis using Biolog® EcoPlatesTM. Sci. Total Environ. 928, 172360 (2024).

Yarwood, S. A. The role of wetland microorganisms in plant-litter decomposition and soil organic matter formation: a critical review. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 94, 1–17 (2018).

Ferreira, V., Elosegi, A., Tiegs, S. D., Von Schiller, D. & Young, R. Organic Matter Decomposition and Ecosystem Metabolism as Tools to Assess the Functional Integrity of Streams and Rivers-A Systematic Review. Water 12, 3523 (2020).

Sarmento, H., Morana, C. & Gasol, J. M. Bacterioplankton niche partitioning in the use of phytoplankton-derived dissolved organic carbon: Quantity is more important than quality. ISME J. 10, 2582–2592 (2016).

Lee, J. Z. et al. Metagenomics reveals niche partitioning within the phototrophic zone of a microbial mat. PLOS ONE 13, e0202792 (2018).

Auladell, A. et al. Seasonal niche differentiation among closely related marine bacteria. ISME J. 16, 178–189 (2022).

Connell, S. D. & Ghedini, G. Resisting regime-shifts: The stabilising effect of compensatory processes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 30, 513–515 (2015).

Moss, J. A., Nocker, A., Lepo, J. E. & Snyder, R. A. Stability and change in estuarine biofilm bacterial community diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5679–5688 (2006).

Yin, W., Wang, Y., Liu, L. & He, J. Biofilms: The Microbial “Protective Clothing” in extreme environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 3423 (2019).

Nocker, A. & Camper, A. K. Selective removal of DNA from dead cells of mixed bacterial communities by use of ethidium monoazide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1997–2004 (2006).

Hintz, W. D. & Relyea, R. A. A review of the species, community, and ecosystem impacts of road salt salinisation in fresh waters. Freshw. Biol. 64, 1081–1097 (2019).

Kefford, B. J. et al. The definition of species richness used by species sensitivity distributions approximates observed effects of salinity on stream macroinvertebrates. Environ. Pollut. 159, 302–310 (2011).

Rotter, S., Heilmeier, H., Altenburger, R. & Schmitt-Jansen, M. Multiple stressors in periphyton – comparison of observed and predicted tolerance responses to high ionic loads and herbicide exposure. J. Appl. Ecol. 50, 1459–1468 (2013).

Vendrell-Puigmitja, L. et al. Effects of an hypersaline effluent from an abandoned potash mine on freshwater biofilm and diatom communities. Aquat. Toxicol. 230, 105707 (2021).

United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2012 Edition of the Drinking Water Standards and Health Advisories. (2012).

Chase, J. M. Stochastic community assembly causes higher biodiversity in more productive environments. Science 328, 1388–1391 (2010).

Brislawn, C. J. et al. Forfeiting the priority effect: Turnover defines biofilm community succession. ISME J. 13, 1865–1877 (2019).

Bender, E. A., Case, T. J. & Gilpin, M. E. Perturbation experiments in community ecology: theory and practice. Ecology 65, 1–13 (1984).

Klindworth, A. et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e1–e1 (2013).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Prodan, A. et al. Comparing bioinformatic pipelines for microbial 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. PLOS ONE 15, e0227434 (2020).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2012).

Parks, D. H. et al. A complete domain-to-species taxonomy for Bacteria and Archaea. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1079–1086 (2020).

Nappi, J. et al. Differential priority effects impact taxonomy and functionality of host-associated microbiomes. Mol. Ecol. 32, 6278–6293 (2023).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package (2022).

Harris, T. D. & Graham, J. L. Preliminary evaluation of an in vivo fluorometer to quantify algal periphyton biomass and community composition. Lake Reserv. Manag. 31, 127–133 (2015).

Echenique-Subiabre, I. et al. Application of a spectrofluorimetric tool (bbe BenthoTorch) for monitoring potentially toxic benthic cyanobacteria in rivers. Water Res. 101, 341–350 (2016).

Garland, J. L. Analysis and interpretation of community-level physiological profiles in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 24, 289–300 (1997).

Garland, J. L., Mills, A. L. & Young, J. S. Relative effectiveness of kinetic analysis vs single point readings for classifying environmental samples based on community-level physiological profies (CLPP). Soil Biol. 33, 1059–1066 (2001).

Garland, J. L. Potential and limitations of BIOLOG for microbial community analysis. Method Microb. Community Anal. 1–7 (1999).

Costa, P. S. et al. Metagenome of a microbial community inhabiting a metal-rich tropical stream sediment. PLOS ONE 10, e0119465 (2015).

Lopes, L. D. et al. Genomic and metabolic differences between Pseudomonas putida populations inhabiting sugarcane rhizosphere or bulk soil. PLOS ONE 14, e0223269 (2019).

Preston-Mafham, J., Boddy, L. & Randerson, P. F. Analysis of microbial community functional diversity using sole-carbon-source utilisation profiles – a critique. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 42, 1–14 (2002).

Lin, H. et al. Recovery trajectories and community resilience of biofilms in receiving rivers after wastewater treatment plant upgrade. Environ. Res. 199, 111349 (2021).

Flemming, H.-C. & Wuertz, S. Bacteria and archaea on Earth and their abundance in biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 247–260 (2019).

Martinez, A. S. et al. Variations in benthic fluxes of sediments near pier pilings and natural rocky reefs. Mar. Environ. Res. 177, 105640 (2022).

Mayer-Pinto, M. et al. Physical and biogenic complexity mediates ecosystem functions in urban sessile marine communities. J. Appl. Ecol. 60, 480–493 (2023).

Kahlert, M. & McKie, B. G. Comparing new and conventional methods to estimate benthic algal biomass and composition in freshwaters. Env. Sci. Process. Impacts 16, 2627–2634 (2014).

Pérez-Calpe, A. V., Larrañaga, A., Von Schiller, D. & Elosegi, A. Interactive effects of discharge reduction and fine sediments on stream biofilm metabolism. PLOS ONE 16, e0246719 (2021).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Garland, J. L. & Mills, A. L. Classification and Characterization of Heterotrophic Microbial Communities on the Basis of Patterns of Community-Level Sole-Carbon-Source Utilization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57, 2351–2359 (1991).

Fox, J. & Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression. (Sage, Thousand Oaks (CA), 2019).

R. V. Lenth. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 1.11.0-003 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank Milly Caley, Maria Marinho, Aiym Duisen and Alec Brodie for their assistance in the field. We thank the staff and students at the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, in Madrid, particularly Ana Carlota Gracia Sancha and Maria Conejero Moreno, for their assistance in laboratory sample processing. RF was supported by the University of Sydney RTP and Murrell scholarships. This study has received funding from the AQUACOSM-plus project of the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 871081 and Transnational Access project SalNutFun. Additional funds were received from The University of Sydney WG Murrell funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: R.F., M.G.M., M.M.P, E.M.M., Sample collection and processing, R.F., M.G.M., M.M.P, E.M.M, Bioinformatic analyses and data visualisation: R.F., Statistical analyses: R.F., E.M.M., Initial drafting of manuscript: R.F. All authors edited and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fuggle, R., Matias, M.G., Mayer-Pinto, M. et al. Multiple stressors affect function rather than taxonomic structure of freshwater microbial communities. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 11, 60 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00700-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00700-2