Abstract

Elucidating the temporal dynamics of complex microbial consortia is crucial for engineering robust microbiome. We investigated prokaryotic evolution in pit mud, a centuries-old engineered environment used in Chinese liquor fermentation. Metagenomic analysis of 120 pit mud samples across different ages revealed a transition from generalist-dominated to specialist-enriched communities. This shift was characterized by decreased hydrolytic potential and increased organic acid metabolism, with key taxonomic changes including declines in Proteiniphilum and Petrimonas, and increases in Methanobacterium and Caproicibacter. The mature specialist community accelerates the short-chain organic acids turnover through syntrophic fatty acid oxidation, methanogenesis, and carbon chain elongation, maintaining ecosystem stability. While nutrient availability primarily shapes early stages community interactions, environmental stress becomes a dominant factor in mature systems. These insights into long-term prokaryotic adaptation provide a foundation for the rational design of resilient, functionally optimized microbial communities for biotechnological applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microbiome engineering has emerged as a promising approach to address challenges in human health, agriculture, and environmental management1. However, significant hurdles remain in establishing long-term functional stability of microbial communities2. Recent perspectives suggest that these challenges may stem from insufficient consideration of ecological principles governing microbial community assembly and persistence3. Of these principles, the dynamics of functional traits and their interactions within the community remain among the least explored aspects in microbiome engineering research, presenting a critical knowledge gap.

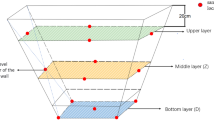

Fermented food systems offer tractable models for studying microbial ecology in situ due to their reproducible microbiomes4,5,6,7. Specifically, the traditional Chinese strong-flavor liquor (CSFL) fermentation system is an engineered environment refined over centuries for industrial production. In this system, grain is fermented under solid-state conditions in a sealed pit, with the walls and bottom covered by a layer of mud known as pit mud (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). This pit mud harbors a diverse and complex microbial community8,9,10 that engages in intricate metabolic interactions with the fermenting substrate, contributing unique flavors to the final product11,12.

A To produce CSFL, water-soaked grains, predominantly sorghum, are steamed and mixed with a fermentation starter. This mixture, known as jiupei, is then placed in a fermentation pit covered by pit mud. Within the pit, jiupei undergoes simultaneous saccharification and spontaneous solid-state fermentation due to the activity of fungi and bacteria. This fermentation process generates lactate, acetate, and ethanol, which are absorbed by the pit mud, serving as an energy source for microorganisms and raw material for the biosynthesis of longer fatty acids. The fatty acids diffuse throughout the jiupei, contributing to the unique flavor of CSFL. After ~40 days of fermentation, the jiupei is taken out and distilled to produce fresh CSFL. B An empty fermentation pit. The fermentation pit is a pit or hole in the ground and covered with a layer of pit mud. C The workers fill the pit with jiupei. D The pit is then covered with a layer of mud to seal in the jiupei and create an anaerobic environment, which encourages the growth of specific microorganisms that are responsible for the fermentation process. We would like to acknowledge the Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. for providing photos.

The pit mud microbiome undergoes successive perturbations during repeated CSFL production cycles over decades or even centuries, and represents distinct development stages11,12,13. This process exemplifies top-down microbiome engineering, where the desired functional outcomes drive the selection and adaptation of microbial communities over time8. It creates natural chronosequences of pit mud, spanning timescales from years to centuries, providing an unparalleled opportunity to investigate long-term microbial community dynamics in situ8,11.

While previous studies have provided valuable insights into the taxonomic and compositional shifts in pit mud microbiomes across varying ages8,11,13,14,15,16,17, the functional dynamics and ecological mechanisms governing assembly and maturation in these ecosystems remain incompletely understood. These studies have revealed a dynamic evolution of the pit mud microbiome with age, significantly impacting liquor quality. Metagenomic analyses have identified key genes and metabolic pathways responsible for flavor compound synthesis, highlighting the crucial role of microbial succession in liquor production. Tao et al.18 pioneered read-based annotation of three pit mud samples (25–50 years), identifying foundational caproate biosynthesis pathways. Subsequent work by Fu et al.15 reconstructed 703 metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from 20 pit mud samples, establishing comprehensive taxonomic and functional profiles. Ren et al.19 compared artificial and natural pit mud systems across ages using 187 MAGs, while Li et al.20 analyzed 32 samples to delineate functional divergences between young and aged pit mud communities. However, these studies primarily focused on snapshots of different pit mud ages rather than tracking the temporal succession patterns of microbial communities and their metabolic functions. A systematic investigation of the dynamic changes in pit mud microbial communities over time remains to be conducted.

In this study, we employed genome-resolved metagenomics across a pit mud chronosequence spanning 100 years (n = 120), physicochemical data, to elucidate functional and taxonomic transitions in pit mud microbiomes over centennial timescales. Under this study design, we tested the following hypotheses: (1) Prokaryotic functional potential follows successional patterns shaped by environmental filtering and assembly processes; (2) Ecosystem-level organic acid metabolism correlates with genomic signatures of community maturation; (3) Specific microbial lineages possess genomic adaptations enabling age-dependent dominance. Elucidating the drivers of assembly and function optimization will provide fundamental insights into microbial ecosystem development over long anthropogenic timescales, potentially informing strategies for engineering stable and functional prokaryotes across various applications.

Results

Long-term liquor fermentation enriches nutrients in pit mud

We observed usage duration-dependent changes in pit mud physicochemical properties during the long-term CSFL production (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 2). pH decreased from weakly alkaline (P3) to weakly acidic (P100), while organic matter (OM), dissolved organic carbon (DOC), total carbon (TC), and total nitrogen (TN) significantly increased. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) showed age-dependent accumulation: lactate, acetate, and butyrate peaked in P100; propionate and caproate increased steadily. Among inorganic ions, NH4+, Cl-, and PO43- exhibited significant accumulation with pit age. The buildup of ions resulted in a marked increase of EC in old pits. Notable correlations among pit mud physicochemical properties were revealed by Pearson correlation analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Metagenomic reconstruction reveals novel microorganisms in the pit mud

Metagenomics analysis of 120 pit mud samples yielded 4082 medium-quality MAGs with CheckM-estimated completeness ≥70 and contamination ≤5 (Supplementary Data 1)21. Dereplication produced 634 representative MAGs (rMAGs), comprising 569 (89.74%) bacterial and 65 (10.26%) archaeal rMAGs (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Data 2). Bacterial rMAGs predominantly belonged to Firmicutes A (175 rMAGs), Bacteroidota (86), Firmicutes G (49), and Firmicutes B (46), while archaeal rMAGs were primarily Halobacteriota (30), Thermoplasmatota (20), and Methanobacteriota (15) (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Data 2).

A The phylogenetic tree is based on 400 universal markers for prokaryotes. The blue, green, red and orange squares around the tree denote the existence of rMAGs in P3, P10, P30, and P100, respectively. B The proportion of the cultured and uncultured taxa of the rMAGs determined using the GTDBtk. C Venn diagrams shows the overlap of the rMAGs in the pit mud samples from different ages.

Of the 634 rMAGs, only 198 (31.23%) matched known genera, with the remaining genomes distributed across uncultured lineages at various taxonomic levels: genus (162 rMAGs, 25.55%), family (132, 20.82%), order (64, 10.09%), class (72, 11.36%), and phylum (6, 0.95%) (Fig. 2B). This indicates most rMAGs are novel compared to the GTDBtk database. Venn diagram shows overlap of rMAGs across different pit ages (Fig. 2C). Total rMAGs decreased from 292 in P3 to 221 in P30 before increasing to 309 in P100, reflecting fluctuating richness of pit mud prokaryote with age.

A core microbiome of 78 rMAGs persisted across all ages, representing 68.23–79.09% relative abundance (Supplementary Data 3, Supplementary Fig. 4A). The core rMAGs were primarily Bacteroidota (13), Halobacteriota (5), Firmicutes A (25), and Firmicutes G (5) (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Age-unique rMAGs numbered 131 (P3), 102 (P10), 32 (P30), and 122 (P100), contributing 14.2–19.0% relative abundance (Supplementary Data 4, Supplementary Fig. 4B). Unique rMAGs belonged largely to Chloroflexota, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidota.

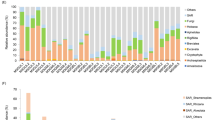

Prokaryotes dynamics over the pit age are marked by specific genera

Taxonomic analysis revealed dynamic compositional shifts across pit ages. Bacterial dominance decreased progressively (64.90–75.38% relative abundance), while archaea abundance increased consistently from 25.31 to 32.34% with pit age (Supplementary Data 2, Supplementary Fig. 5). The dominant bacterial phyla were Bacteroidota (16.3–38.50%), Firmicutes A (5.52–15.40%), Firmicutes G (2.51–18.58%), Firmicutes B (3.47–11.37%), and Chloroflexota (0.34–13.77%) (Supplementary Fig. 5). Archaea belonged to Halobacteriota (18.65–24.30%), Methanobacteriota (4.09–11.48%), and Thermoplasmatota (0.35–1.88%) (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Temporal community dynamics revealed distinct successional patterns (Fig. 3). The relative abundance profiles of the top 20 genera (Fig. 3A) revealed Methanoculleus, Proteiniphilum, and Petrimonas as predominant taxa. Alpha diversity analysis (Fig. 3B) demonstrated significantly higher Shannon indices in P10 compared to P30 and P100 (p < 0.01), while beta diversity analysis through principal co-ordinates analysis (PCoA) (Fig. 3B) confirmed significant age-related compositional differences (R² = 0.11, p < 0.001). These results collectively indicate a clear temporal succession pattern in pit mud microbial communities, characterized by peak diversity in early stages followed by increased selection pressure in older pits. Linear regression identified key age-associated genera including Proteiniphilum (r2 = 0.2, FDR < 0.001), Petrimonas (r2 = 0.17, FDR < 0.001), UBA4882 (r2 = 0.08, FDR < 0.001), Syner-03 (r2 = 0.07, FDR < 0.001), SR-FBR-E99 (r2 = 0.09, FDR < 0.001), Methanobacterium A (r2 = 0.16, FDR < 0.001), Caproicibacter (r2 = 0.1, FDR < 0.001), UBA4871 (r2 = 0.23, FDR < 0.001), and Pseudomonas_E (r2 = 0.1, FDR < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 6).

A Alluvial plot illustrating the relative abundances of the top 20 genera. The numbers of rMAGs are indicated in parentheses. B Shannon diversity index Kraken2 based speices compostion. Paired comparasion is employed wilcoxon rank-sum test. Only statistically significant results are presented, denoted as * for FDR < 0.05, ** for FDR < 0.01, and *** for FDR < 0.001. C Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) plot of MAG composition across the four ages, with overall community differences assessed using the permutational MANOVA.

Physicochemical properties displayed significant correlations with top 20 genera (Supplementary Fig. 7). The genera Proteiniphilum, Petrimonas, T78, Methanothrix, Pseudomonas E, Syner−03, and SR − FBR − E99 were negatively correlated with OM and ions, while Methanoculleus, Methanobacterium A, Caprobacter, Methanobacterium C, UBA4871, Methanosarcina, Syntrophaceticus, Sedimentibacter and UBA4844 were positively associated with nutrient levels. Random forest modeling identified 23 age-discriminatory genera, achieving 89.77% variance explanation (Supplementary Fig. 9). Key predictive taxa included Methanobacterium_A (increasing) and Proteiniphilum (decreasing), highlighting their utility as maturation biomarkers.

Long-term fermentation reduces polymer degradation capacity in pit muds

Metabolic pathway reconstruction employed stringent criteria requiring ≥80% completeness for enzyme systems and pathways (Supplementary Data 5–7), with manual curation based on KEGG module completeness (Supplementary Data 8). Key metabolic genes and pathways in abundant rMAGs ( > 0.5% relative abundance) are presented in Fig. 4. We quantified metabolic capacity through gene abundance-weighted metrics (Supplementary Data 9), revealing significant age correlations via Spearman analysis (Supplementary Data 10, Supplementary Fig. 10).

Different color gradients in the relative abundance (log transformed), CAZyme, peptidase, lipase, and energy conserving relevant enzymes represent their quantities among rMAGs. Differentially shaded tiles represent the completeness of the displayed metabolic pathways, including none, partial (100% > completeness > 80%), and complete three levels. The specific key genes and completeness definition involved in each metabolic pathway is mentioned in the Supplementary Data 8.

To elucidate polymer degradation, we analyzed peptidase, lipase, and carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZyme) diversity and occurrence, which catalyze macromolecule hydrolysis (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 7, Supplementary Data 10). Polymer-degrading genes were enriched in Firmicutes E, Firmicutes H, Acidobacteriota, Armatimonadota, Planctomycetota, Bacteroidota, and Verrucomicrobiota (Supplementary Data 11). However, considering abundance, CAZymes were predominantly encoded by Bacteroidota (e.g., MAG246.1, MAG254.1), Firmicutes A (MAG554.1, MAG545.1), Firmicutes G (MAG300.1, MAG109.1), and Armatimonadota (MAG394.1, MAG397.1), while peptidase and lipase genes were mainly found in Bacteroidota, Firmicutes A, Firmicutes G, and Halobacteriota (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 11). These phyla likely represent major polymer degraders in pit mud. Notably, capacity for lipase (rho = −0.38, FDR < 0.001), glycoside hydrolase (GH, rho = −0.50, FDR < 0.001), carbohydrate esterase (CE, rho = −0.37, FDR < 0.001), carbohydrate binding module (CBM, rho = −0.46, FDR < 0.001), and polysaccharide lyase (PL, rho = −0.4, FDR < 0.001) decreased with age, while auxiliary activities (AA, rho = 0.46, FDR < 0.001) increased (Supplementary Data 10, Supplementary Fig. 10).

Short chain organic acid metabolic capability increases over pit age

Lactate, acetate, propionate, and butyrate are major anaerobic polymers hydrolysis byproducts and important flavor compounds in CSFL12,22. High potential for alcohol and lactate metabolism via acetyl-CoA was observed (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 9), with the relative abundance of rMAGs containing the two pathways was 43.64% and 51.00%, respectively (Supplementary Data 7, Supplementary Data 9). Lactate metabolizer abundance significantly decreased with pit age (rho = −0.32, FDR < 0.001), while the alcohol metabolism capacity was stable (Supplementary Data 10, Supplementary Fig. 10). Bacteroidota genera Petrimonas and Proteiniphilum had the highest lactate catabolism potential, which declined over time. In contrast, Firmicutes A genera Caproicibacter, Sedimentibacter, and various uncultured members became predominant lactate utilizers in older pits (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 9). Despite stable alcohol degradation (Supplementary Data 10), dominant alcohol-utilizing genera shifted from Petrimonas, uncultured SR-FBR-E99, and Syner-03 in the young pits (P3, P10) to Pseudomonas E, Caproicibacter, and Caproicibacterium in the old pits (P30, P100) (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 9).

We examined fatty acid biosynthetic microbes in pit mud prokaryote, since short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are important intermediates and expected CSFL metabolites12. The butyrate biosynthesis pathway was identified in 230 rMAGs, comprising 34.21–36.92% across four ages (Supplementary Data 7 and Supplementary Data 9). While the relative abundance of butyrate biosynthesizers remained stable, their composition significantly changed with pit age. Specifically, Petrimonas, uncultured T78, and UBA4882 members dominated the butyrate biosynthesis group in P3 but decreased in P100, whereas Caproicibacter, Caproicibacterium, Sedimentibacter and Pseudomonas E increased in P100 (Supplementary Data 7 and Supplementary Data 9). Regarding fatty acid chain elongation, there are two routes to obtain longer fatty acids, the fatty acid biosynthesis (FAB) pathway and the reverse beta oxidization (RBO) pathway23. We observed a significant increase in the abundance (8.70–25.59%) of genomes (176 rMAGs) encoding the FAB pathway within the pit mud prokaryote with pit age (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Data 9). Most of the rMAGs responsible for FAB pathway were assigned to uncultured UBA4882, Caproicibacterium, Caproicibacter, and Pseudomonas E (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Data 7). Conversely, the RBO pathway, was observed in 67 rMAGs, accounting for 4.40–7.50% of the whole community across the pits of four ages, with most of them being assigned to Pseudomonas E, uncultured UBA4851, and UBA5314 (Supplementary Data 7 and Supplementary Data 9). These results indicate that the FAB pathway is essential for fatty acid chain elongation in the pit mud prokaryote.

The syntrophic oxidation of SCFAs with methanogenic partners was proposed as a key step in anaerobic process22. According to the elevated butyrate and acetate concentrations, the pit mud prokaryotes exhibited increased potential of syntrophic butyrate (rho = 0.20, FDR < 0.05) and acetate (rho = 0.28, FDR < 0.01) oxidation with pit age, whereas propionate degradation potential decreased (rho = −0.24, FDR < 0.05) (Supplementary Data 10, Supplementary Fig. 10). We identified 99 rMAGs with butyrate oxidation pathways, the relative abundce increase from 16.77% in P3 to 23.63% in P100 (Supplementary Data 9). Petrimonas, Caproicibacterium, UBA4844, and UBA5389 members dominated the butyrate oxidation group in each age, whereas species affiliated within Pseudomonas E and uncultured T78 considerably increased in P100 (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 9). Propionate degradation group comprised 72 rMAGs (Supplementary Data 7), and the relative abundance of these rMAGs decreased from 23.38% in P3 to 16.46% in P100, with Petrimonas, Proteiniphilum, and uncultured UBA4882 mainly contributing to the metabolic capacity of propionate oxidation (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 9). For syntrophic acetate oxidation, 27 and 111 rMAGs encoded the Wood-Ljungdahl (WLP) and glycine cleavage pathways (GCP), respectively (Supplementary Data 7). Average relative abundance was 3.01% for WLP and 10.61% for GCP, suggesting GCP is dominant (Supplementary Data 9). Syntrophaceticus members, including known acetate oxidizer S. schinkii (MAG106.1) were main WLP microbes (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 7). With respect to GCP, we found that Sedimentibacter, uncultured UBA4844, and UBA4975 were abundant genera (Supplementary Data 9). Additionally, 25 WLP and 104 GCP rMAGs were identified uncultured, indicating abundant novel acetate oxidizers in pit mud (Supplementary Data 7).

We ubiquitously identified methanogenesis pathways in the archaeal rMAGs of this study (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 7). The hydrogenotrophic pathway in 37 of 65 archaea was most prominent, significantly increasing (rho = 0.35, FDR < 0.001) from 17.38% in P3 to 29.03% in P100 (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Data 7). Methanoculleus (9 rMAGs), Methanobacterium C (5 rMAGs), and mixotrophic methanogen Methanosarcina members (9 rMAGs) mainly contributed to the hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis across the pits of the four ages (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 7, Supplementary Data 9). The relative abundance of Methanoculleus first rose from 8.78% in P3 to 17.79% in P10 before decreasing to 14.54% in P100. Notably, Methanobacterium A (2 rMAGs) significantly increased from 0% to 7.82% with pit age (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 7, Supplementary Data 9). The proportion of acetotrophic methanogens fluctuated from 9.32% in P3 to 5.07% in P100 with no significant correlation with pit age (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Data 7). Methanothrix (2 rMAGs) and Methanosarcina (9 rMAGs) were the abundant acetotrophic methanogens. We also identified methylated compounds (i.e., methanol, dimethylamine, and monomethylamine) metabolism producing methane in the communities (Supplementary Data 7, Supplementary Data 9). The methylotrophic methanogenesis capacity increased from 4.86% to 7.61% with the pit age, with Methanobacterium C, Methanosarcina, and Methanobacterium A dominating this group (Supplementary Data 7, Supplementary Data 9). Additionally, 20 Thermoplasmatota rMAGs were identified as methylotrophs, including 17 uncultured Methanomassiliicoccales (Supplementary Data 7, Supplementary Data 9). Complementing methanogenesis, diverse phyla encoded supporting energetic and metabolic functions (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 12, Supplementary Note). The presence of various electron transfer modules highlights the importance of energy conservation pathways in CSFL fermentation.

Ecological factors shaping prokaryotic structure and function

Ecological drivers were analyzed through Mantel tests and Pearson correlations, revealing pit age as the strongest predictor of both taxonomic (rho = 0.39, P < 0.001) and function (rho = 0.33, P < 0.001) variation (Fig. 5A). Potassium showed significant correlations with taxonomy (rho = 0.24, p < 0.001) and function (rho = 0.22, p < 0.001). Moderate correlations occurred between microbial community and MC, EC, NH4+, TN, Cl- and DIC (p < 0.01). Weak/non-significant associations occurred with SO42−, TC, DOC, Na+, PO43−, organic acids and C/N ratio (p > 0.05). PCoA confirmed significant age-related divergence in taxonomy (R2 = 0.11, P < 0.001) and functional structure (R2 = 0.09, P < 0.001) by pit age (Fig. 3C, Supplementary Fig. 10A). Additionally, significant time-decay relationships were observed for composition (R2 = 0.16, P < 0.001) and function (R2 = 0.13, P < 0.001) similarities versus age gap (Supplementary Fig. 11B, C). Despite both similarities decreasing along with the gap age of pits, our results suggest that there is high taxonomic variability but similar functional structure across pit mud prokaryotes during the development of pits. (Supplementary Fig. 11D).

A Correlations between the environmental variables and microbial community. Pearson’s correlation coefficients are represented by the color gradient in the heatmap, and the asterisk symbolizes the statistical significance adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. Edge width represents the Mantel’s coefficients while edge color corresponds to the statistical significance. B Path diagram for SEM showing only significant direct and indirect effects of variables on taxonomic and functional compositions. Composition is represented by the PC1 from the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity-based principal coordinate analysis. Numbers adjacent to the arrows are standardized path coefficients. Blue and red arrows represent positive and negative paths, respectively. Double-headed arrows indicate covariance between variables, single-headed arrows indicate a one way directed relationship. R2 represents the proportion of variance explained for every dependent variable in the model. The fit of models was evaluated using one-tailed Chi-squared test and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). C The networks represent RMT-based Spearman’s correlations derived from all samples for each pit age, where nodes represent rMAGs, and links between the nodes represent significant correlations. The node size is proportional to its degree, and the color indicates the modules detected by fast greedy modularity optimization.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to evaluate multivariate relationships between communities and environment. Our findings indicate that caproate, which positively relates to butyrate, directly affects both taxonomic (rho = 0.28, P < 0.001) and functional (rho = −0.22, P < 0.001) composition (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, functional composition was mostly determined by taxonomic (r = −0.71, P < 0.001) composition, which was directly influenced by MC (rho = 0.42, P < 0.001), EC (rho = 0.43, P < 0.001), pH (rho = 0.39, P < 0.001), and Cl− (rho = −0.27, P < 0.05). These environmental variables were positively driven by DOC and VS, which were positively and directly affected by pit age.

To gain insight into microbial assembly, we further constructed random matrix theory (RMT)-based Spearman’s rank correlation networks to identify the potential ecological interactions among prokaryotic members of pit mud24. Network analysis revealed shifting interaction patterns (Fig. 5C, Supplementary Data 13). Despite larger MAG datasets in P100, network complexity decreased (Fig. 5C), suggesting enhanced functional integration with age25. The proportion of negative correlations rose from 52.22% in P3 to 90.34% in P30 (Supplementary Data 13), indicating increased competition potentially from nutrient enrichment, which is consistent with “hunger games” hypothesis that competition is more frequent in copiotrophic environment26. Although nutrients continued accumulating in P100, positive links increased to 42.86%, implying enhanced cooperation assists survival under environmental stress27.

Discussion

Temporal studies of microbial communities reveal unique ecological principles that are otherwise inaccessible28. Chronosequence approaches employing space-for-time substitution enable exploration of community dynamics across extended timescales29. Through systematic metagenomic analysis of a 100-year pit mud chronosequence, this study advances our understanding of structure-function relationships in traditional fermentation ecosystems. Our investigation elucidates pit ecosystem ecology while establishing managed chronosequences as model systems for studying microbial community evolution11. These findings provide critical insights for microbial community engineering, revealing three key principles: (1) Functional redundancy enables stability despite taxonomic turnover; (2) Metabolic specialization increases with community maturation; (3) Environmental filtering drives predicted successional patterns.

In complex anaerobic microbial web, cross-feeding cascades likely establish interspecific nutrient cycling in shared pools, enabling continuous turnover that balances stoichiometry and stabilizes communities30,31,32. Our metabolic reconstruction identified four interacting functional groups governing carbon flow (Fig. 6):

-

(1)

Hydrolysis Bacteria (HB): Most abundantly encoding peptidases, lipases, and CAZymes, are generalists that hydrolyze biopolymers into monomers, which were then fermented into H2, CO2, and SCFAs (Fig. 6). Consistent with previous studies15, members of genera Proteiniphilum and Petrimonas belonging to phylum Bacteroidota were major HB within the pit mud.

-

(2)

Fatty Acid Chain-Elongation Bacteria (FCEB): Although SCFAs are key CSFL flavor compounds, uncontrolled accumulation will cause pH decline and community disruption13,33. FCEB convert SCFAs into longer fatty acids (mainly butyrate, caproate) by chain elongation (Fig. 6)12,34. Longer chain fatty acids diffused into the jiupei through the concentration gradient could provide flavoring compounds for CSFL, as well as decrease the organic acids concentration of pit mud18. Elongation occurs via reverse RBO or FAB using ethanol/lactate35. Acetate could be elongated to butyrate via acetyl-CoA36. Butyrate is subsequently used to synthesize caproate with a specific caproyl-CoA: acetate CoA transferase within the pit mud37. We detected high butyrate biosynthesis capacity in this study, likely produced abundant butyrate and caproate for the CSFL. Surprisingly, FAB pathway capacity increased over time in this study despite lower theoretical efficiency than RBO35. Previous study also reported high expression levels of genes related to FAB responsible for the elongation of short chain carboxylates to medium chain in mixed culture38. Dominant FCEB were Firmicutes lineages like Caproicibacter, Caproicibacterium, Sedimentibacter and UBA4882 in the present study. Caproicibacterium and Sedimentibacter have been reported to be well-known dominant butyrate and caproate producers within the pit mud11,39,40.

Hydrogenase, formate dehydrogenases, and energy conservation pathways are abbreviated as shown in the Supplementary Data 7. ETC electrontransfer chain, FCEB fatty acid chain elongation bacteria, FAB fatty acids biosynthesis, RBO reverse beta-oxidation, SFOB syntrophic fatty acid oxidation bacteria, SBOB syntrophic butyrate- oxidizing bacteria, SPOB syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria, SAOB syntrophic acetate-oxidizing bacteria.

-

(3 & 4)

Syntrophic fatty acid oxidation bacteria (SFOB) andmethanogens: SFOB-methanogen coupling removes SCFAs to produce CH4 (Fig. 6), as well as reducing the acid stress for the community. Propionate/butyrate get converted to acetate, formate, and H2, while acetate undergoes acetoclastic methanogenesis or a syntrophic degradation between acetate oxidizers and hydrogenotrophic methanogens30. Despite hydrogenotrophic and acetoclastic methanogenic pathways were simultaneously detected, the hydrogenotrophic methanogens like Methanoculleus and Methanobacterium were the dominant methanogens within the pit mud. Moreover, the minor presence of acetoclastic methanogens (Methanosarcina and Methanothrix) but the ubiquitous presence of potential SFOBs strongly suggests that SCFAs are syntrophically oxidized in the pit mud. By integrating the fatty acid chain elongation and syntrophic methanogenesis, communities rapidly remove organic acids, and prevent strong acidification during long-term CSFL fermentation to guarantee the stability of pit mud ecosystem.

Metagenomic analysis assisted with the identification of novel bacteria in various anaerobic environments41,42,43. A large number of novel species was observed across the four groups. Previous metagenomic analysis of the pit mud found that only 32.97% of the DNA sequences were taxonomically classified15. Consistently, our metagenomic data showed that almost 70% of the rMAGs (436 of 634 rMAGs) were defined as the uncultured species, implying the large knowledge gaps in microorganisms within long-term CSFL fermentation. We detected SCFA oxidation pathways in abundant unclassified organisms, indicated the potential role of novel species in syntrophic fatty acid oxidation within the pit mud. Most of the novel SFOBs were affiliated to the Firmicutes lineages classes, which contain well-known SFOBs such as S. schinkii and S. methylbutyratica30,44. Fatty acids biosynthesis pathways were found in the unclassified species, e.g., MAG294.1 (genus uncultured UBA4839, class Clostridia) and MAG56.1 (genus uncultured T78, class Anaerolineae). Methanogenesis that uses oxidized carbon like CO2 as a terminal electron acceptor is crucial for carbon cycling in anaerobic environment45. In this study, we found 17 rMAGs that encoded methylotrophic methanogenesis pathway belonging to the uncultured order Methanomassiliicoccales (Supplementary Data 7). The order Methanomassiliicoccales is a novel methanogen lineage proposed for the phylum Thermoplasmatota46.

Pit mud communities are mostly shaped by their local physicochemical conditions11. Consistent with the previous studies16,17, our results showed that the pit mud properties displayed nutrient enrichment but acidification and salinization during long-term CSFL fermentation (Fig. 7). The metabolic cross-feeding cascades shifted accordingly (Fig. 7), reflected in taxonomic and functional succession patterns (Supplementary Fig. 10). Here we propose a conceptual model to comprehend the microbial succession pattern with increasing pit age: Our findings suggest a shift from a ‘generalist-dominated’ to a ‘specialist-enriched’ community along the pit mud chronosequence. The early-stage prokaryote exhibits high functional diversity, particularly in hydrolytic capabilities, enabling the exploitation of diverse substrates. As the pit mud matures, we observe a transition towards a community with enhanced metabolic potential for organic acid production and utilization, indicating functional specialization in response to the selective pressures of the fermentation environment. (Fig. 7).

Ferm Fermentation, Lac lactate, Eth ethanol, Fo formate, Ac acetate, PR propionate, BT butyrate, CA caproate, FA fatty acd, HB hydrolysis bacteria, FCEB fatty acid chain elongation bacteria, SFOB syntrophic fatty acid oxidation bacteria, Bac Bacteroidota, Fir Firmicutes, Chl Chloroflexota, Arm Armatimonadota, Syn Synergistota, Ther Thermoplasmatota, Me-bac Methanobacterium, Me-thrix Methanothrix, Me-sarcina Methanosarcina, Me-culleus Methanoculleus.

In the early stages of pit mud development (P3), we observed low carbon availability (Table 1) coupled with high diversity and cooperative interactions (Figs. 1, 5C). This aligns with the “hunger games” hypothesis proposed by recent studies26, suggesting that nutrient scarcity promotes cooperation for efficient resource utilization26,47. The initial community exhibited functional versatility, characterized by abundant hydrolytic potential (Fig. 4), a trait commonly observed in early-stage ecosystems48,49. This generalist strategy enables the community to exploit diverse polymeric substrates, initiating the complex fermentation cascade that produces SCFAs, amino acids, and eventually longer fatty acids, CO2, and methane30.

As the pit mud matures over decades of CSFL fermentation, we observe a significant shift in community composition and function. The accumulation of metabolites from fermentation (Table 1) correlates with a decrease in the relative abundance of hydrolytic bacteria (HB) and an increase in short-chain fatty acid-oxidizing bacteria (SFOB) and hydrogenotrophic methanogens (Fig. 7). This transition is accompanied by an increase in negative associations (Supplementary Data 13), consistent with the “hunger games” hypothesis that predicts more frequent competition in nutrient-rich environments26.

We propose that this shift represents a transition from a generalist-dominated to a specialist-enriched community (Fig. 7), evidenced by: (i) a decrease in the relative abundance of genes encoding hydrolytic enzymes and an increase in genes involved in organic acid metabolism (Supplementary Fig. 10), and (ii) a taxonomic shift from HB like Proteiniphilum and Petrimonas to specialized organisms such as the FCEB Caproicibacter, syntrophic bacteria Syntrophomonas, and hydrogenotrophic methanogens Methanoculleus. This specialist-enriched community, with its enhanced capacity for organic acid turnover, likely plays a crucial role in maintaining pH stability and community resilience16,50.

In the deep aging phase, despite continued acidification (Table 1) and further decline of HB, we observed increased species diversity and positive correlations (Fig. 2, Supplementary Data 13). This apparent contradiction to the “hunger games” hypothesis26 suggests that additional factors, such as environmental stress (e.g., pH and salinity), significantly influence community dynamics in mature engineered prokaryotes. Our structural equation modeling (SEM) confirms the direct influence of these stress factors on microbial community composition (Fig. 5B).

The insights gained from this study have broad implications for prokaryote engineering. While our conservative pathway completeness threshold ensures robust functional predictions, we acknowledge that this approach may underestimate the prevalence of distributed metabolic networks across our 634 MAGs. Nevertheless, our systematic characterization of metabolic handoffs between functional guilds establishes a valuable framework for engineering stable and efficient microbial communities. The process flows from hydrolyzers through carbon elongators and syntrophs to methanogens. The comprehensive genomic repository generated here not only enables targeted cultivation and interaction studies but also lays the groundwork for future investigations using advanced techniques such as genome-scale metabolic modeling and proteome-resolved network inference. These findings and resources hold profound implications for biotechnology applications, from optimizing industrial fermentation processes to enhancing environmental remediation systems, ultimately advancing our ability to harness and engineer complex microbial communities for sustainable solutions.

Methods

Sample collection

Pit mud samples were collected from Luzhou Lao Jiao Co., Ltd, in Luzhou city, Sichuan province, China (105.5021° E, 28.9024° N) from August 2020 to April 2021 after one batch of CSFL fermentation for each pit. Three parallel fermentation pits continually used for ~3 (P3), ~10 (P10), ~30 (P30), and ~100 years (P100) were selected for sampling, respectively. For each pit, ten representative composite samples were collected using a systematic spatial sampling strategy (Supplementary Fig. 1). The pit walls were sampled at four vertical levels, with both shallow and deep samples obtained at each level. Samples from identical heights and depths were pooled to create composite samples. The pit bottom was sampled using a pentagon-based approach, with five sampling points collected at both shallow and deep depths and subsequently pooled. In total, 120 pit mud samples from 12 pits across four ages were collected for physicochemical analysis and metagenomic sequencing (Supplementary Data 14).

Physicochemical analysis

Water content and OM were determined by gravimetric analysis. TC and TN were measured using an elemental analyzer (vario EL cube, Elementar, Germen). Electrical conductivity (EC) and pH were determined using EC indicator (SG3, Mettler Toledo, USA) and pH meter (HM-25G, TOA DKK, Tokyo) in a 1:10 (w/v) soil-water suspension. DOC and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) were quantified using a Shimadzu TOC analyzer (TOC-VE, Shimadzu, Japan) after extracting samples with deionized water and filtering through 0.45 μm membrane filters. Inorganic ion concentrations (NH4+, K+, Na+, NO2-, NO3-, SO42-, Cl-, and PO43-) were measured using ion chromatography (ICS-1500, Dionex, USA). following water extraction and membrane filtration51. The concentrations of lactate, acetate, propionate, butyrate, valerate, and caproate were determined by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), as previously described52. Analysis was performed using a Waters E2695 HPLC system equipped with a 2998 PDA detector. Lactic acid was analyzed using a Waters Atlantis T3 column (5 μm, 4.6 mm × 250 mm) at 30 °C with 20 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 2.7) as the mobile phase at 0.7 mL/min. SCFAs were analyzed using a SEPAX Carbomix H-NP 5:8 column (5 μm, 7.8 mm × 300 mm) at 55 °C with 2.5 mM H2SO4 as the mobile phase at 0.6 mL/min. All compounds were detected at 210 nm with an injection volume of 10 μL and quantified using external standard curves. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

DNA extraction, sequencing, assembly and mapping

Total DNA was extracted via the cetyl-trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method53. Briefly, samples were homogenized with preheated CTAB extraction and incubated at 65 °C for 30 min. The mixture was then treated with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1), followed by chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) extraction. DNA was precipitated with isopropanol, washed with 70% ethanol, and resuspended in sterile water. DNA quality and quantity were assessed using both agarose gel electrophoresis and a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000, Thermo, USA). DNA samples were sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform in Shanghai Majorbio Biopharm Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) to generate paired-end reads (2 × 150 bp), ensuring that the sequencing data volume for each sample exceeded 20 gigabases.

Raw reads were quality filtered using Trimmomatic v0.39 with a quality cutoff of 30 and minimum length cutoff of 100 bp54. Filtered reads from each site and age were co-assembled using metaSPAdes v3.14.0 (-k 19, 39, 59, 79, 99). Co-assembled contigs were binned into MAGs using the MetaWrap v1.3.1 with metabat2 v2.12.1, maxbin2 v2.2.6 (minimum contig length 1000), and concoct v1.0.055,56,57,58. MAGs were combined with Binning_refiner v1.4 and assessed for quality using CheckM v1.0.12 (completeness ≥ 70 and contamination ≤ 5)59,60. RPKM (reads per kilobase per million mapped reads) of the MAGs for each sample was predicted using BBMap v38.90 (minid = 0.99)61. The filtered MAGs from all samples were dereplicated to obtain representative genomes (rMAG) using dRep v2.6.2 (-pa 0.90, -sa 0.95, -nc 0.60)62. Taxonomy of rMAGs was estimated by GTDBtk v1.5.0 (GTDB Release 202)63. The relative abundance of rMAG in each sample was determined using following formula:

The community composition was also determined using Kraken264.

Gene annotation and metabolic reconstruction

For rMAGs, open reading frames were predicted and translated using Prokka v1.14.665. The rMAGs were examined for carbohydrate/protein/lipid hydrolysis potential by identifying CAZyme, peptidase, and lipase families using the CAZyme database66,67, MEROPS database68, and lipase engineering database69, respectively. The genes involved in syntrophic SCFA degradation, methanogenisis pathway, energy conserving mechanisms, H2/formate metabolism were determined through blastp (v2.9.0 + ) with database containing relevant enzymes downloaded from UniProt70 and NCBI-NR database (minimum length of 50 amino acids, >40% amino acid similarity). Glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, alcohol metabolism, lactate metabolism, reverse tricarboxylic acid cycle, SCFA biosynthesis, fatty acid elongation, nitrogen metabolism, and sulfur metabolism were predicted using KofamKOALA v1.3.0 with the KO database71. KEGG module completeness was calculated using MicrobeAnnotator v2.0.572. The resulting annotation of genes was manually curated through rpsblast with a conserved domain database73. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using PhyloPhlAn 3.0, which classifies genomes based on the presence of up to 400 universal prokaryotic markers74. MAGs were included if they contained more the 100 of these markers to enable robust phylogenetic inference.

Network construction

The networks of prokaryotic community were constructed based on the rMAGs’ relative abundance datasets using molecular ecological network analysis pipeline24. To enhance the statistical power and reliability of our correlation analysis, we applied a detection threshold where MAGs present in at least 30% of samples were retained. This approach helps mitigate potential biases from transient taxa while maintaining a comprehensive view of the community composition. RMT-based strategy was applied to calculate the appropriate correlation coefficient cutoff75. The network modules were detected based on fast greedy modularity optimization.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis were performed in R v4.0.3. One-way ANOVA with LSD tests compared environmental variables between age groups. Linear regression revealed relationships between pit age and environmental variables, taxonomy, and metabolism. To further model pit age as a function of prokaryotes composition, we developed full random forest models for pit samples by regressing the relative abundance of all genera against the pit age with randomForest Rpackage. The environmental variables and prokaryotic composition data were scaled using function decostand in package vegan v2.5 with standardize and Hellinger methods, respectively. Dissimilarity matrix of environmental variables and biotic data were calculated using vegdist function with Euclidean and Bray-Curtis methods, respectively. Mantel tests evaluated correlations between environmental and biotic matrices using mantel_test function in linkET package. Alpha diversity based on Kraken2 species composition and PCoA were analyzed using phyloseq package76. Pearson and Spearman correlation analysis were performed using stats and ade4 package. The rate of the time-decay relationships was represented by the slope in the linear regression model between the gap in years between two pits versus prokaryotic taxonomic and functional community composition similarity. FDR-adjusted p values were calculated by Benjamini-Hochberg method.

Data availability

The metagenomic sequence data used in this study can be found under BIG Sub Genome Sequence Archive (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA007136) under the bio-project number PRJCA009789. All metagenomic analyses were performed with the metaWRAP pipeline, a modular wrapper suite for genome-resolved metagenomics. The pipeline version, installation instructions, dependencies, and underlying software are publicly documented at https://github.com/bxlab/metaWRAP. Exact command-line parameters and software versions used for quality control, assembly, binning, refinement, reassembly, taxonomic profiling, and functional annotation are provided in the “Methods” section. The downstream statistical analysis and visualizations were carried out in R (version 4.3). Custom code used for diversity calculations, differential abundance testing, correlation analysis, Mantel test, SEM analysis and random forest models were written specifically for this project and are not packaged or deposited in a public repository. These short, project-tailored scripts are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request from qualified researchers.

Code availability

All metagenomic analyses were performed with the metaWRAP pipeline, a modular wrapper suite for genome-resolved metagenomics. The pipeline version, installation instructions, dependencies, and underlying software are publicly documented at https://github.com/bxlab/metaWRAP. Exact command-line parameters and software versions used for quality control, assembly, binning, refinement, reassembly, taxonomic profiling, and functional annotation are provided in the “Methods” section. The downstream statistical analysis and visualizations were carried out in R (version 4.3). Custom code used for diversity calculations, differential abundance testing, correlation analysis, Mantel test, SEM analysis and random forest models were written specifically for this project and are not packaged or deposited in a public repository. These short, project-tailored scripts are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request from qualified researchers.

References

Sheth, R. U., Cabral, V., Chen, S. P. & Wang, H. H. Manipulating bacterial communities by in situ microbiome engineering. Trends Genet. 32, 189–200 (2016).

Lawson, C. E. et al. Common principles and best practices for engineering microbiomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 725–741 (2019).

Albright, M. B. N. et al. Solutions in microbiome engineering: prioritizing barriers to organism establishment. ISME J. 16, 331–338 (2021).

Wolfe, B. E., Button, J. E., Santarelli, M. & Dutton, R. J. Cheese rind communities provide tractable systems for in situ and in vitro studies of microbial diversity. Cell 158, 422–433 (2014).

Jin, G., Zhu, Y. & Xu, Y. Mystery behind Chinese liquor fermentation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 63, 18–28 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Kastman, E. K., Guasto, J. S. & Wolfe, B. E. Fungal networks shape dynamics of bacterial dispersal and community assembly in cheese rind microbiomes. Nat. Commun. 9, 336 (2018).

Wolfe, B. E. & Dutton, R. J. Fermented foods as experimentally tractable microbial ecosystems. Cell 161, 49–55 (2015).

Tao, Y. et al. Prokaryotic communities in pit mud from different-aged cellars used for the production of Chinese strong-flavored liquor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 2254–2260 (2014).

Zhao, J. S., Zheng, J., Zhou, R. Q. & Shi, B. Microbial community structure of pit mud in a Chinese strong aromatic liquor fermentation pit. J. Inst. Brew. 118, 356–360 (2012).

Liang, H. et al. Analysis of the bacterial community in aged and aging pit mud of Chinese Luzhou-flavour liquor by combined PCR-DGGE and quantitative PCR assay. J. Sci. Food Agric. 95, 2729–2735 (2015).

Chai, L.-J. et al. Mining the factors driving the evolution of the pit mud microbiome under the impact of long-term production of strong-flavor Baijiu. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 87, e00885–00821 (2021).

Qian, W. et al. Cooperation within the microbial consortia of fermented grains and pit mud drives organic acid synthesis in strong-flavor Baijiu production. Food Res. Int. 147, 110449 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Prokaryotic communities in multidimensional bottom-pit-mud from old and young pits used for the production of Chinese Strong-Flavor Baijiu. Food Chem. 312, 126084 (2020).

Sun, H. et al. Metabolite-based mutualistic interaction between two novel Clostridial species from pit mud enhances butyrate and caproate production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 88, e00484–00422 (2022).

Fu, J. et al. Metagenome and analysis of metabolic potential of the microbial community in pit mud used for Chinese strong-flavor liquor production. Food Res. Int. 143, 110294 (2021).

Sun, Z. et al. Prokaryotic diversity and biochemical properties in aging artificial pit mud used for the production of Chinese strong flavor liquor. 3 Biotech 7, 1–9 (2017).

Zhang, Q., Yuan, Y., Liao, Z. & Zhang, W. Use of microbial indicators combined with environmental factors coupled with metrology tools for discrimination and classification of Luzhou-flavoured pit muds. J. Appl. Microbiol. 123, 933–943 (2017).

Tao, Y. et al. The functional potential and active populations of the pit mud microbiome for the production of Chinese strong-flavour liquor. Micro Biotechnol. 10, 1603–1615 (2017).

Ren, D. et al. Metagenomics-based insights into the microbial community dynamics and flavor development potentiality of artificial and natural pit mud. Food Microbiol. 125, 104646 (2025).

Li, Z. et al. Structure and metabolic function of spatiotemporal pit mud microbiome. Environ. Microbiome 20, 10 (2025).

Bowers, R. M. et al. Minimum information about a single amplified genome (MISAG) and a metagenome-assembled genome (MIMAG) of bacteria and archaea. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 725–731 (2017).

Pind, P. F., Angelidaki, I. & Ahring, B. K. Dynamics of the anaerobic process: effects of volatile fatty acids. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 82, 791–801 (2003).

Wu, Q. et al. Opportunities and challenges in microbial medium chain fatty acids production from waste biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 340, 125633 (2021).

Deng, Y. et al. Molecular ecological network analyses. BMC Bioinf. 13, 1–20 (2012).

Zhang, B. et al. Biodegradability of wastewater determines microbial assembly mechanisms in full-scale wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 169, 115276 (2020).

Dai, T. et al. Nutrient supply controls the linkage between species abundance and ecological interactions in marine bacterial communities. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–9 (2022).

Hays, S. G., Patrick, W. G., Ziesack, M., Oxman, N. & Silver, P. A. Better together: engineering and application of microbial symbioses. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 36, 40–49 (2015).

Faust, K., Lahti, L., Gonze, D., de Vos, W. M. & Raes, J. Metagenomics meets time series analysis: unraveling microbial community dynamics. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 25, 56–66 (2015).

Walker, L. R., Wardle, D. A., Bardgett, R. D. & Clarkson, B. D. The use of chronosequences in studies of ecological succession and soil development. J. Ecol. 98, 725–736 (2010).

McInerney, M. J., Sieber, J. R. & Gunsalus, R. P. Syntrophy in anaerobic global carbon cycles. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 20, 623–632 (2009).

Smith, N. W., Shorten, P. R., Altermann, E., Roy, N. C. & McNabb, W. C. The classification and evolution of bacterial cross-feeding. Front. Ecol. Evol. 7, 153 (2019).

Saha, S. et al. Microbial symbiosis: a network towards biomethanation. Trends Microbiol. 28, 968–984 (2020).

Liang, H., Luo, Q., Zhang, A., Wu, Z. & Zhang, W. Comparison of bacterial community in matured and degenerated pit mud from Chinese Luzhou-flavour liquor distillery in different regions. J. Inst. Brew. 122, 48–54 (2016).

Wu, Q. et al. Medium chain carboxylic acids production from waste biomass: current advances and perspectives. Biotechnol. Adv. 37, 599–615 (2019).

Kim, H., Kang, S. & Sang, B.-I. Metabolic cascade of complex organic wastes to medium-chain carboxylic acids: A review on the state-of-the-art multi-omics analysis for anaerobic chain elongation pathways. Bioresour. Technol. 344, 126211 (2022).

Marius, V., Adina Chuang, H. & Tiedje, J. M. Revealing the bacterial butyrate synthesis pathways by analyzing (meta)genomic data. Mbio 5, e00889 (2014).

Yang, Q. et al. Butyryl/Caproyl-CoA:Acetate CoA-transferase: cloning, expression and characterization of the key enzyme involved in medium-chain fatty acid biosynthesis. Biosci. Rep. 41, BSR20211135 (2021).

Han, W., He, P., Shao, L. & Lü, F. Metabolic interactions of a chain elongation microbiome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84, e01614–e01618 (2018).

Gu, Y. et al. Caproicibacterium amylolyticum gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel member of the family Oscillospiraceae isolated from pit clay used for making Chinese strong aroma-type liquor. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 71, 004789 (2021).

Chai, L.-J. et al. Profiling the Clostridia with butyrate-producing potential in the mud of Chinese liquor fermentation cellar. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 297, 41–50 (2019).

Ziels, R. M., Sousa, D. Z., Stensel, H. D. & Beck, D. A. DNA-SIP based genome-centric metagenomics identifies key long-chain fatty acid-degrading populations in anaerobic digesters with different feeding frequencies. ISME J. 12, 112–123 (2018).

Sierra-Garcia, I. N. et al. In depth metagenomic analysis in contrasting oil wells reveals syntrophic bacterial and archaeal associations for oil biodegradation in petroleum reservoirs. Sci. Total Environ. 715, 136646 (2020).

Timmers, P. H. et al. Metabolism and occurrence of methanogenic and sulfate-reducing syntrophic acetate oxidizing communities in haloalkaline environments. Front. Microbiol. 9, 3039 (2018).

Sieber, J. R., McInerney, M. J. & Gunsalus, R. P. Genomic insights into syntrophy: the paradigm for anaerobic metabolic cooperation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 66, 429–452 (2012).

Lyu, Z., Shao, N., Akinyemi, T. & Whitman, W. B. Methanogenesis. Curr. Biol. 28, R727–R732 (2018).

Iino, T. et al. Candidatus Methanogranum caenicola: a novel methanogen from the anaerobic digested sludge, and proposal of Methanomassiliicoccaceae fam. nov. and Methanomassiliicoccales ord. nov., for a methanogenic lineage of the class Thermoplasmata. Microbes Environ. 28, 244–250 (2013).

Gralka, M., Szabo, R., Stocker, R. & Cordero, O. X. Trophic interactions and the drivers of microbial community assembly. Curr. Biol. 30, R1176–R1188 (2020).

Nicol, G. W., Tscherko, D., Embley, T. M. & Prosser, J. I. Primary succession of soil Crenarchaeota across a receding glacier foreland. Environ. Microbiol. 7, 337–347 (2005).

Jayakumar, A., O’mullan, G., Naqvi, S. & Ward, B. B. Denitrifying bacterial community composition changes associated with stages of denitrification in oxygen minimum zones. Micro Ecol. 58, 350–362 (2009).

Dahiya, S., Sarkar, O., Swamy, Y. & Mohan, S. V. Acidogenic fermentation of food waste for volatile fatty acid production with co-generation of biohydrogen. Bioresour. Technol. 182, 103–113 (2015).

Zhong, X.-Z. et al. A comparative study of composting the solid fraction of dairy manure with or without bulking material: performance and microbial community dynamics. Bioresour. Technol. 247, 443–452 (2018).

Chai, L.-J. et al. Zooming in on butyrate-producing Clostridial consortia in the fermented grains of baijiu via gene sequence-guided microbial isolation. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1397 (2019).

Griffiths, R. I., Whiteley, A. S., O’Donnell, A. G. & Bailey, M. J. Rapid method for coextraction of DNA and RNA from natural environments for analysis of ribosomal DNA- and rRNA-based microbial community composition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 5488–5491 (2000).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Uritskiy, G. V., DiRuggiero, J. & Taylor, J. MetaWRAP—a flexible pipeline for genome-resolved metagenomic data analysis. Microbiome 6, 1–13 (2018).

Kang, D. D. et al. MetaBAT 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ 7, e7359 (2019).

Wu, Y.-W., Simmons, B. A. & Singer, S. W. MaxBin 2.0: an automated binning algorithm to recover genomes from multiple metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 32, 605–607 (2016).

Alneberg, J. et al. Binning metagenomic contigs by coverage and composition. Nat. Methods 11, 1144–1146 (2014).

Song, W.-Z. & Thomas, T. Binning_refiner: improving genome bins through the combination of different binning programs. Bioinformatics 33, 1873–1875 (2017).

Parks, D. H., Imelfort, M., Skennerton, C. T., Hugenholtz, P. & Tyson, G. W. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25, 1043–1055 (2015).

Bushnell, B. BBMap: A Fast, Accurate, Splice-Aware Aligner. Report No. LBNL-7065E (Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 2014).

Olm, M. R., Brown, C. T., Brooks, B., Banfield, J. F. dRep: a tool for fast and accurate genomic comparisons that enables improved genome recovery from metagenomes through de-replication. ISME J. 11, 2864–2868 (2017).

Chaumeil, P.-A., Mussig, A. J., Hugenholtz, P., Parks, D. H. GTDB-Tk: a Toolkit to Classify Genomes with the Genome Taxonomy Database (Oxford University Press, 2020).

Wood, D. E., Lu, J. & Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 20, 257 (2019).

Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Lombard, V., Golaconda Ramulu, H., Drula, E., Coutinho, P. M. & Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D490–D495 (2014).

Yin, Y. et al. dbCAN: a web resource for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, W445–W451 (2012).

Rawlings, N. D. et al. The MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors in 2017 and a comparison with peptidases in the PANTHER database. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D624–D632 (2018).

Fischer, M. & Pleiss, J. The Lipase Engineering Database: a navigation and analysis tool for protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 319–321 (2003).

Consortium, U. UniProt: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D506–D515 (2019).

Aramaki, T. et al. KofamKOALA: KEGG ortholog assignment based on profile HMM and adaptive score threshold. Bioinformatics 36, 2251–2252 (2020).

Ruiz-Perez, C. A., Conrad, R. E. & Konstantinidis, K. T. MicrobeAnnotator: a user-friendly, comprehensive functional annotation pipeline for microbial genomes. BMC Bioinf. 22, 11 (2021).

Lu, S. et al. CDD/SPARCLE: the conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D265–D268 (2020).

Asnicar, F. et al. Precise phylogenetic analysis of microbial isolates and genomes from metagenomes using PhyloPhlAn 3.0. Nat. Commun. 11, 2500 (2020).

Zhou, J., Deng, Y., Luo, F., He, Z. & Yang, Y. Phylogenetic molecular ecological network of soil microbial communities in response to elevated CO2. MBio 2, e00122–00111 (2011).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 8, e61217 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 32201993 and 31901658), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant numbers 2024T170375 and 2023M741512). We would like to thank the Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. for providing the samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. and X.Z.Z. analyzed the metagenomic data and wrote the first draft. L.J.C., X.J.Z. and Z.M.L. edited large parts of the manuscript. G.Q.L., T.Y.T., L.F.L., R.Z. and H.Y. conducted sampling, DNA extraction, and provided the chemical data. S.T.W., S.Y.Z., C.H.S., J.S.S. and Z.H.X. designed the experiment, edited the manuscript and conceived the study. All authors reviewed and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, Y., Zhong, X., Chai, L. et al. Prokaryotic evolution shapes specialized communities in long term engineered pit mud ecosystem. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 11, 186 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00805-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00805-8