Abstract

Oral intake of probiotics has been shown to positively impact depression, anxiety, stress and cognition. Recently, an effort was made to more objectively assess their impact on brain structure and function. However, there has been no exhaustive systematic assessment of outcomes of these studies, nor the techniques utilised. Therefore, we performed a systematic review on randomised, placebo-controlled trials assessing the effects of oral probiotic interventions on brain health by imaging or electrophysiology techniques in human adults. Of 2307 articles screened, 26 articles comprising 19 studies, totalling 762 healthy subjects or patients with various diseases, were ultimately included. The quality of most studies was high. Overall, probiotic intake appears to modify resting state connectivity and activity, decrease involvement of several brain regions during negative emotional stimulation, and improve sleep quality. Several studies found correlations between brain outcomes and clinical symptom ratings, supporting the relevance of brain imaging and electrophysiology techniques in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Accumulating evidence suggests that the gut-brain axis, a complex, bidirectional communication system between the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system (CNS), influences human health. Much of the effect on gastrointestinal physiology can be attributed to the gut microbiota, an interconnected community of microorganisms that colonise the gut. The gut microbiota can mediate communication along the gut-brain axis via several key pathways including neural (such as stimulation of the vagus nerve1, the enteric nervous system (ENS)2, or spinal afferents3), humoral (such as the release of neurotransmitters4, tryptophan5, and short-chain fatty acids6,7), and immune pathways (via the release of cytokines and microbiota-immune system interactions8).

The microbiota and its metabolites have been implicated to play a role in brain development, function and health9. Preclinical studies in mice and rats have observed alterations in neurotransmitters10,11, brain structure12, and brain function13,14,15 in response to aberrations of the gut microbiota. The potential link between the gut microbiota, communication along the gut-brain axis, and brain health has been demonstrated in several human studies. For example, patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) have been shown to have a similar microbiota composition as depressed patients, suggesting that alterations of the gut microbiota may be related to the pathogenesis of both disorders16. Furthermore, a prospective study found that individuals with higher anxiety and depression levels at baseline were more likely to develop IBS after one year compared to individuals with lower baseline levels17. Also, in individuals with IBS, cognitive behaviour therapy-related changes on resting state functional connectivity correlated with a gut microbiota change in a recent study18. Finally, the experts who determined the ROME IV diagnostic criteria for IBS have redefined IBS and other functional gastrointestinal disorders as “disorders of gut-brain interactions”, underscoring the relevance of this communication pathway19.

These findings suggest that modifying gut microbiota composition may be an attractive strategy to impact brain function and disease. One approach to such modification is through ingestion of prebiotics, compounds that can promote the growth of beneficial microbes by acting as an energy source, or probiotics, live microbial supplementation that confers a benefit to the host, when consumed in adequate amounts20,21. For example, a recent study investigated the effects of the prebiotic fibre inulin on brain activation in a reward-related, food decision-making task in overweight young adults22. In this two-week intervention, prebiotic ingestion resulted in decreased brain activation towards high-caloric food stimuli in the ventral tegmental area and the orbitofrontal cortex, as assessed by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Focusing on probiotics, Groeger et al. found that an eight-week intervention with Bifidobacterium longum resulted in an improvement of psychometric measures in IBS patients with comorbid anxiety and/or depression23. In addition, several meta-analyses concluded that microbiota modifications by pre- and probiotics positively affect depressive symptoms, with the majority of studies focused on probiotics24,25,26, and psychiatric distress24.

While most evaluations of the effects of probiotics on brain health in humans are based on self-reported symptom ratings, the assessment of brain function via imaging techniques is a more objective method and advocated for by one of the aforementioned reviews24. Further systematic research using quantitative measurements to analyse potential changes in the human brain in response to probiotic interventions is needed. Examples of such quantitative measures to assess expected changes in both brain structure and function are techniques such as (f)MRI, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG), amongst others. These non-invasive and in-depth measurements provide insights into morphometry, activity, and connectivity of the brain, offering a deeper understanding of potential changes due to modulation of the gut-brain axis. In addition, such insights contribute to the understanding of the interplay between complex human functions. Performing measurements during sleep27 or resting state can provide information about spontaneous fluctuations of the brain28, while performance of neurocognitive tasks can give insights about task-related brain activity or connectivity in order to observe stress or emotional responsiveness29,30.

As there is a growing number of studies assessing the effects of probiotics on brain outcomes, this systematic review assesses the effects of probiotic interventions in adults (of any study population, e.g. healthy or diseased) on brain function and structure assessed in randomised, placebo-controlled trials by brain imaging or electrophysiology technologies (including but not limited to (f)MRI, DTI, EEG, MEG).

Results

Trial selection

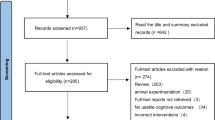

The literature search (with the latest update in August 2025) resulted in a total of 2943 records, of which 2307 records were screened, resulting in 45 articles that were included in a full-text assessment for eligibility. Of these, 26 articles originating from 19 studies were ultimately included in this review (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 2).

Study participants

The 19 studies included a total of 762 healthy subjects or patients with various diseases. Ten of the studies included healthy individuals, of which two studies included women only31,32,33, two studies included men only34,35, and six studies included both women and men36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. Of the studies conducted in healthy individuals, Adikari et al. only included young male football players (18–21 years of age)35, while Takada et al. specifically included medical students preparing for a national qualification examination36.

The remaining studies focused on specific health conditions or diagnoses. Three studies included individuals with sleep problems45,46,47. The other studies included elderly participants with suspected mild cognitive impairment48, cirrhotic patients49, patients with IBS with comorbid anxiety or depression50,51, patients with post-COVID-19 myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)52 and patients with depression undergoing an active anti-depressant treatment plan53,54,55,56.

Probiotic interventions

Of the 19 studies included in this review, 12 studies investigated a product with a single probiotic strain34,35,36,39,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,56, whereas seven studies employed a multi-strain product31,32,33,37,38,40,41,42,43,52,53,54,55 (Table 2). Collectively, these studies included 37 individual strains from 15 different species of 9 bacterial genera. Products containing Bifidobacterium species were investigated in 12/19 studies, Lacticaseibacillus (9/19), Lactiplantibacillus (6/19), Lactobacillus (7/19), Levilactobacillus (1/19), Ligilactobacillus (2/19), Lactococcus (3/19), Streptococcus (3/19) and Pediococcus (1/19). On the species level, the most commonly utilised species were L. paracasei (7/19), L. plantarum (6/19), B. lactis (6/19), B. longum (5/19), L. acidophilus (4/19), and L. helveticus (4/19). The daily bacterial doses ranged from 7.0 × 107 to 1.0 × 1011 colony-forming units (CFU); however, in some cases, the exact doses of individual bacterial strains in the multi-strain product were not reported31,32,33,37,38,40,53,54,55. In addition, one study45 reported the daily dose as grams of the product, not as CFU, leaving the number of bacteria in the product uncertain.

In addition to the wide variety of strains utilised, the intervention length, mode of delivery, placebo utilised, and compliance reporting strategy varied among the included studies. The length of the intervention periods ranged from 28 to 90 days, with most studies (12/19) lasting for approximately four weeks. The products were consumed as a powder with a carbohydrate-based carrier (11/19), as a fermented milk drink (4/19), or as capsules (3/19). Only 6/19 studies reported truly identical placebo products, containing the exact same ingredients except for the addition of the probiotic strains, 9/19 were overtly not comparable, and for 4/19 the quality of the comparison could not be determined from the information provided. Notably, in two studies, the probiotic product included 2.5 g fructo-oligosaccharide, a known prebiotic, which was not present in the placebo treatment49,52,57. Furthermore, in another study, the probiotic tablets but not the placebo contained theanine, an amino acid that is known to affect the CNS45. When considering compliance, 6/19 studies reported the exact proportions of compliant participants36,41,42,43,44,46,47,53,54,55. In these studies, compliance was high (83–100%). A total of 4/19 studies reported cut-off compliance values for inclusion in the final data analysis31,45,49,53,54,55, and 9/19 studies did not report any values on compliance32,33,34,35,37,38,39,40,48,50,51,52,56.

Additional information on probiotic interventions, such as commercial product name, product manufacturer and study funding source, can be found in Supplementary Table 8.

Structural brain outcomes

Structural connectivity. Structural connectivity, i.e., anatomical connections mostly by bundles of neuronal axons, was assessed in two of the included studies using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI). While Bagga et al. found no effects of a multi-strain probiotic intervention on fractional anisotropy and mean diffusivity (two measures of DTI) in a study population of healthy young adults38, Yamanbaeva et al. reported increased post-intervention mean diffusivity in the right uncinate fasciculus (a white matter fibre tract) after placebo but not probiotic intervention54. They also observed typical negative correlations between fractional anisotropy and mean diffusivity solely in the probiotics group54.

Morphometry. Morphometric effects were assessed in four of the included studies using voxel-based or surface-based morphometry techniques40,43,48,53. On the whole-brain level, Schaub et al. reported increased grey matter volume in the calcarine and lingual sulcus, both associated with the visual cortex (without differences in thickness, gyrification or sulcus depth) after any intervention, but no intervention-related differences53. Furthermore, Rode et al. observed lower grey matter volume in a cluster covering the left supramarginal gyrus and superior parietal lobule (both associated with emotion, attention, and memory) after probiotic compared to placebo intervention43. White matter volume seems to have been not affected, as reported in the methods description, but not described in the results section43. However, no intervention group*time effects were observed for grey matter volume in the studies by Schaub et al.53 and Ascone et al.40, nor for white matter volume in the study by Ascone et al.40. Moreover, Ascone et al. did not find intervention group*time effects on the hippocampal structure40. In addition to investigating changes in grey and white matter volume, Asaoka et al. specifically investigated brain atrophy changes using a modified voxel-based morphometry technique and detected an increase in grey matter atrophy in the whole brain (which also differed significantly between the intervention groups) and in the volume-of-interest for Alzheimer’s disease upon placebo but not probiotic intervention48. The differences were dependent on the brain atrophy severity at baseline48.

Functional brain outcomes

Resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rsfMRI). Seven studies assessed brain function using fMRI tools. Out of those, four studies (all utilising four-week multi-strain probiotic interventions) employed rsfMRI38,40,43,54 (Table 3). A fifth study performing rsfMRI did not report on the obtained results separately but instead used it for correlation with task-based fMRI31 (Table 3). The scanning duration varied from five to ten minutes, and participants were instructed to have their eyes open40, closed31,43, or it was not specified38,54. The data analyses were conducted with targeted or untargeted approaches.

In a healthy population, Bagga et al. observed significantly lower resting functional connectivity, i.e., synchronised brain activity, in the probiotics compared to the placebo group in the default mode network — the typical resting state brain network — and in pre- and postcentral gyri38. In a similar healthy population, Rode et al. reported altered (increased and decreased) resting state functional connectivity after probiotics compared to placebo intervention between regions of the default mode network and regions involved mainly in attention and motor functions, amongst others43. Ascone et al. did not find any probiotic effect on resting state functional connectivity originating from bilateral hippocampal regions (mainly associated with memory functions) to any other part of the brain40.

In a clinically depressed patient cohort, Yamanbaeva et al. reported significant time*group interactions deriving from increased resting state functional connectivity after probiotics intervention and decreased connectivity post-placebo from the precuneus (a brain region with a broad spectrum of highly-integrated tasks)54. Furthermore, they also observed altered connectivity post-probiotics from the left superior parietal lobule/supramarginal gyrus (regions involved in emotion, attention and memory)54. Most of those functional connectivity alterations remained significant even after correcting for significant baseline differences54.

Task-based fMRI. The tasks performed during fMRI acquisition were of emotional and/or cognitive nature with a possible stress component in all six studies31,32,37,41,42,50,53,55 (Table 4). Despite some overlap in study and emotional paradigm design, the results were heterogenous with little consistency across the different studies. Several of the studies reported no effects of the probiotic intervention on some aspects of task-based fMRI32,41,42,50,53,55. On the other hand, some studies reported lower engagement of a variety of brain regions (precuneus, mid and posterior cingulum, hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, amygdala, mid and posterior insula, frontal and temporal cortices) during mostly negative emotions, i.e., unpleasant stimuli or angry and fearful faces, after probiotic intervention compared to placebo31,37,42,50. In addition, some studies reported lower engagement of brain regions (anterior cingulum, putamen) during neutral emotional stimuli37,53. In contrast to the emotional paradigms, the number of cognitive tests was lower, and tests were more heterogeneous in design and resulted in less prominent probiotic effects on brain function.

Correlation between fMRI outcomes. Tillisch et al. analysed probiotic effects on rsfMRI originating from midbrain regions, amongst others involved in perception and emotional regulation, that showed altered connectivity during an emotional faces attention task (periaqueductal grey, somatosensory cortex, and insula, Table 3 & 4)31. The probiotic-induced resting state network correlated negatively with task-induced seed regional brain activity in the probiotic group, which was less strongly correlated in the placebo group31. Additionally, the detected probiotic-induced resting state network correlated positively with task-induced regional connectivity31.

Cerebral blood flow. One study assessed cerebral blood perfusion (by arterial spin labelling [ASL] MRI), which was not affected significantly (intervention group*time effect) by probiotic intervention, despite group and time effects54.

Resting state functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). In a healthy study population, Mutoh et al. employed fNIRS in order to assess brain activity before (during screening and at baseline) and after a six-week intervention with B. breve M-16 V44. Prefrontal cortex laterality index (i.e., left-right difference in brain activity) at rest (3 minutes, sitting) did not differ significantly between the interventions when assessing the study population as a whole44. However, when analysing the subgroups with high anxiety state and trait scores, respectively, prefrontal laterality index at rest was significantly lower post-probiotic intervention compared to placebo44.

Task-based (fNIRS). In the same study by Mutoh et al., prefrontal cortex laterality index during stress evoked by an arithmetic task was not significantly affected by the probiotic intervention (overall and subgroup analyses)44.

Resting state magnetoencephalography (MEG). In MEG and electroencephalography (EEG), the frequency bands beta (13–30 Hz; normal consciousness, active concentration), alpha (8–13 Hz; wakefulness, passive attention, relaxation), theta (4–8 Hz; drowsiness, early states of sleep), and delta (0–4 Hz; deep sleep) are utilised to assess brain activity58. Wang et al. assessed the effects of a four-week intervention with B. longum 1714 on resting state brain activity by MEG (5 min, eyes closed)39. The probiotic intervention resulted in higher theta band power in the bilateral inferior, middle, and superior frontal cortex and the bilateral anterior and middle cingulate cortex compared to placebo39. In addition, the probiotic group exhibited lower beta-2 band power in the bilateral fusiform gyrus, bilateral hippocampus, left inferior and superior temporal and bilateral middle temporal cortex, and the left cerebellum compared to placebo39. The authors concluded that the probiotic intervention resulted in changes in resting state brain activity associated with increased vitality and stress-related neural responses39.

Task-based MEG. In the same study by Wang et al., utilising a “Cyberball game” as a social stress paradigm, probiotic intake compared to placebo resulted in higher theta band power in one cluster, which included the right inferior, bilateral middle, and superior frontal cortex, left anterior and bilateral middle cingulate cortex, and the right supramarginal gyrus39. Moreover, the probiotic intervention also presented higher alpha band power in one cluster, including the right inferior, bilateral middle, and superior frontal cortex, the bilateral anterior and middle cingulate cortex, and the right supramarginal gyrus in both conditions (in- and exclusion) of the paradigm, regions involved in the neural processing of social stress39. However, no significant time*group interaction effects were observed39.

Resting state electroencephalography (EEG). Unlike MEG, which is utilised to record the brain’s magnetic fields, EEG is utilised to record the brain’s electrical fields59. Two studies performed resting state EEG to assess probiotic effects on brain activity (Table 5). In healthy male subjects, Kelly et al. observed lower F3 (placement of the electrode at frontal location 3) zero crossings, second derivative (a measurement that encodes wave frequency; a reduced number of zero crossings indicates fewer high-frequency components at this recording location) post eight-week intervention with L. rhamnosus JB-1 vs placebo, but not compared to baseline34. Kikuchi-Hayakawa et al. found significantly lower theta power, but no significant differences in the alpha or beta power, or beta/alpha ratio between a four-week intervention with L. casei Shirota and placebo, in subjects with sleeping problems47.

Automated EEG. Malaguarnera et al. performed a 90-day parallel intervention with B. longum plus fructo-oligosaccharides in cirrhotic patients and reported no differences in automated EEG (resting, at 30, 60, 90, 120 days) between the probiotic group compared to placebo or compared to baseline within groups49 (Table 5).

Task-based EEG. In addition to utilising EEG during rest, EEG has also been employed to measure brain activity during task performance (Table 6). Adikari et al. conducted an eight-week intervention to assess the effects of L. casei Shirota on anxiety-induced physiological parameters in competitive football players, using the digit vigilance test, a cognitive task35. In pairwise comparisons, the probiotic group exhibited significantly higher absolute theta and delta brain wave power, brain waves associated with sleep and relaxed state, but not alpha, beta or gamma brain wave power, compared to placebo at week four but not week eight35. In addition, Kikuchi-Hayakawa et al. investigated the effects of a four-week intervention with L. casei Shirota on brain activity in the auditory oddball task47. They found no differences for alpha or beta power, or beta/alpha ratio but did observe significantly lower theta power during the task in the probiotic group in the afternoon47. Furthermore, Li et al. conducted a 30-day intervention with P. acidilactici in patients with MDD on active antidepressant treatment plans to examine the effects of the probotic intervention on brain activity during the “Doors Guessing Task”, a paradigm to assess reward processing56. Stimulus-preceding negativity waveform amplitude (an indication of award anticipation) was significantly greater in the probiotic group compared to placebo post-intervention56. Furthemore, at post-intervention, stimulus-preceding negativing waveform amplitude was increased compared to baseline in the probiotic group, with no significant changes in the placebo group56.

Sleep EEG. Three studies assessed sleep quality by objective measures using EEG (Table 7). Takada et al. investigated whether an intervention with L. casei Shirota improved sleep quality in medical students subjected to academic stress, utilising overnight single-channel EEG recordings36. Probiotic intake prevented a reduction in N3 sleep (deep sleep) as the exam approached compared to placebo and increased delta power during the first sleep cycle (measured as index of sleep intensity) of more than 20% as the exam approached36. All mentioned parameters were reported as significant as time*group interaction effect36.

In individuals with sleep problems, Nakagawa et al. conducted a four-week intervention to assess the effects of L. helveticus MIKI-020, its fermentation products, and theanine45. Sleep EEG was assessed for three days before and at the end of intervention; however, brain waves were not reported45. Similarly, Ho et al. examined the effects of an intervention with L. plantarum PS128 on sleep quality by a miniature polysomnography46. N3% (percentage of deep sleep out of total sleep) of the probiotic group was significantly lower compared to placebo46. Alpha, beta and delta waves were not significantly affected46. Not when assessed as a whole, but when overall sleep was broken down into sleep stages (N1, N2, N3, and REM), they found that theta power % during N1 (light sleep stage that occurs right after sleep onset) of the probiotic group on day 15 (mid-study) was significantly lower compared to placebo46. There were no significant differences when considering N2, N3, or REM46.

Brain tissue metabolite concentrations

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy outcomes (MRS). In post-COVID-19 ME/CFS patients, a study found significant time*group interaction effects indicating increased creatine (free creatine and phosphocreatine) levels in left frontal white and grey matter and increased choline (free choline, glycerophosphocholine and phosphorylcholine) levels in the thalamus, in favour of the probiotic intervention over the placebo52. While choline levels were not affected by any intervention compared to baseline, creatine and N-acetyl aspartate levels increased significantly compared to baseline, mainly in the probiotic group, in some parts of the thalamus, frontal, precentral, paracentral, and parietal white and grey matter52.

Correlation of brain imaging or electrophysiology results with other parameters

Although out of the immediate scope of this systematic review, the included studies’ attempts to understand the modes of action and clinical outcomes of probiotic-mediated effects on brain structure and function are worth mentioning. The following non-imaging outcomes were assessed: general health, mood, emotional regulation, stress, cognition and memory, sleep quality, gastrointestinal health, immune response, signalling molecules, faecal microbiota and metabolites, heart rate (variability), and skin conductance.

Probiotic intervention-related correlations between brain imaging or electrophysiology results and other parameters were reported on in seven of the 19 studies. The remaining studies either did not assess correlations or did not report the results of such analyses.

The majority of studies assessed correlations between outcomes on emotional regulation, depression and anxiety. In one of those studies, after a four-week intervention with a multi-strain probiotic product in healthy subjects, Bagga et al. observed that brain activity in the cerebellum and cingulum during an emotional recognition task (with neutral and unpleasant stimuli) correlated negatively with improved general well-being in the probiotic but not the placebo group37. Similarly, the study by Pinto-Sanchez et al. found that after six-week intervention with B. longum in IBS patients, decreased engagement of the amygdala during a negative emotional task (fearful faces) correlated with lowered depression scores in the probiotic, but not the placebo group50. In the probiotic group, the reduced engagement of the amygdala was also found more frequently in IBS patients experiencing relief of gastrointestinal symptoms following the intervention50. Contrary, Schaub et al. could not find correlations between brain activity during a negative emotional task (fearful faces) and depression or anxiety ratings after a four-week adjunctive multi-strain probiotic intervention in depressed patients on active anti-depressant medication plans53. In the same depressed study population, Yamanbaeva et al. found probiotics-induced changes in structural connectivity (fractional anisotropy and mean diffusivity) in the left uncinate fasciculus and decreased functional resting state connectivity between amygdala and superior parietal lobule that correlated with improved depression scores in the probiotic, but not placebo group54. No correlation between voxel-based morphometry outcomes and psychological symptoms was observed53.

Li et al. also performed some correlations to explore the relationship between subjective and objective indicators of depression and anhedonia56. They observed a significant negative correlation between changes in stimulus-preceding negativity waveform amplitude and changes in anxiety and depression scores in the probiotic group. They also observed a weak positive correlation between changes in stimulus-preceding negativity waveform amplitude and changes in anhedonia scores56. Furthermore, after a four-week intervention with B. longum 1714 in healthy subjects, energy and vitality ratings were positively correlated with changes in averaged theta band power and were negatively correlated with changes in beta-3 band power during resting state, solely in the probiotic group39.

Other studies assessed correlations between aspects of cognition, especially working memory. For instance, Schneider et al. found hippocampal activation to be correlated with reaction time during a working memory task (n-back task), with inverse directions after probiotics vs placebo intervention in a depressed patient cohort and significantly different correlations between the groups55. In terms of signalling molecules, they found no correlation between brain activation in the memory task and the levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor55. Another study found a negative correlation between stress-induced working memory changes (assessed by digit span backward scores after socially-evaluated cold pressor test) and brain activity in bilateral inferior prefrontal cortex during cognitive control (by colour-word Stroop task) in the probiotics but not the placebo group32. This correlation also differed significantly between groups for the right interior prefrontal cortex32. Brain activity in the dorsolateral, dorsomedial and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex was activated during the cognitive control task, and probiotics-induced changes in faecal microbiota composition (especially increased relative abundance of the Ruminococcaceae_UCG-003 genus) did not correlate significantly33. In addition, brain activity during an emotional task did not correlate with changes in microbiota composition53. In the IBS study50, higher faecal probiotic abundance (assessed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction, qPCR) was significantly correlated with decreased amygdala activation during the negative emotional task51. Faecal probiotic abundance also correlated with increased plasma butyric acid concentrations, which in turn correlated with decreased amygdala activation, as well as decreased anxiety and depression scores51. Furthermore, increased plasma concentrations of tryptophan, N-acetyl tryptophan, and pentadecanoic acid correlated significantly with decreased amygdala activation, in the entire study population and also when assessing the probiotic group, but not the placebo group, separately51. Other glycine-conjugated bile acids or free fatty acids did not correlate with the fMRI findings51.

Although some of the above-mentioned correlations include parameters with potential stress components, only one study assessed correlations on direct stress-related outcomes. As such, Wang et al. found that B. longum 1714-induced changes during a social stressor (cyberball game, exclusion condition) in neural activity, i.e., theta and alpha band power, correlated positively with changes in feelings of belonging, self-esteem, control, and meaningful existence, but not after placebo39. According to the methods section, they also assessed correlations to other psychological ratings, but it seems that those were not significant (since not reported in the results section)39.

One of the sleep EEG studies, Ho et al., found moderate to high correlations between the changes in alpha, beta and delta power % and depression scores in participants with insomnia after 30 days of supplementation with L. plantarum PS12846.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to exhaustively report on the effects of probiotic intake on human brain health utilising investigations with brain imaging or electrophysiology outcomes. Interestingly, despite a relatively small number of studies and considerable heterogeneity between the study protocols in terms of study populations, probiotic interventions, and brain outcome assessment techniques and analyses thereof, we could identify a number of consistent results. Collectively, probiotic intake appears to modify resting state brain activity and functional connectivity, decrease the involvement of several brain areas, especially during negative emotions, and improve sleep quality.

A fundamental strength of this systematic review is its focus on objective multimodal brain outcome assessment techniques. So far, solely some of the findings from six studies obtained by functional magnetic resonance imaging had been summarised60.

Considering the examined effects, task-based fMRI effects seem to occur most often in response to negative emotions. Although most of these studies focus on mood, the applied emotional tasks often have a cognitive component61,62. The heterogeneity in task-based outcomes might likely arise from methodological differences in the variety of tasks used and data analyses applied, despite all paradigms being well-validated. Furthermore, results may be domain-specific.

Across all studies, no matter the paradigm or analyses performed, probiotics seem to affect most often cingulate regions, hippocampal regions and supramarginal gyrus, with involvement in at least six comparisons (probiotic vs placebo). Additionally, exclusively in the fMRI analyses, precuneus, pre- and postcentral gyrus and amygdala were involved in four comparisons (probiotic vs placebo). Generally, frontal regions seem to be affected quite often in the studies included in this review. The regions that are most commonly affected by probiotic interventions are visualised in Fig. 1. Of note, since the majority of studies applied whole-brain analyses approaches (Supplementary Table 9), it can be assumed that probiotic interventions generally evoked stronger signal changes in those reported brain regions. Probiotic-induced changes in the included EEG and MEG studies, independent of whether they were conducted during rest, sleep or during task performance, most often showed an impact on theta brain waves, which are indicative of early stages of sleep or drowsiness. Interestingly, the combined findings of this review are consistent with the results of studies that correlate brain connectivity and gut microbiota composition63,64. In a systematic review of 16 such studies, the authors found associations between brain connectivity in the salience (most prominently the insula and cingulate cortex), default mode, and frontoparietal networks and gut microbiota composition and diversity, with low specificity likely due to the heterogeneity of the included studies65. Our systematic review on probiotics’ effects as a potential gut microbiome modulating intervention now adds towards the understanding of directionality and causality.

Brain regions most commonly affected by probiotic interventions. Regions are presented on a standard brain in a axial, b coronal, c sagittal view. Probiotics most often affected the highlighted brain regions: hippocampus (orange), cingulate gyrus (blue), supramarginal gyrus (yellow), precentral gyrus (green), postcentral gyrus (white), amygdala (red), precuneus (brown) - across all studies, independent of paradigm applied, technology used or analyses performed.

Although rsfMRI changes are conceptually predictive of brain responses to specific tasks, only Tillisch et al.31 investigated this in the context of probiotics and negative emotional responsiveness. With resting state conditions being much less demanding than the application of tasks in the brain imaging environment, further investment in such correlative analyses may facilitate the use of especially rsfMRI as a non-invasive surrogate marker for brain and mental health effects of probiotics and simultaneously allow assessment of larger cohorts and/or compromised subjects.

The effects of probiotic intake on brain morphometry and structural connectivity (with alterations traditionally being associated with various diseases) were inconclusive and limited to a few parameters.

Previous studies have established that probiotic supplementation may impact subjectively assessed clinical symptom ratings24,25,26 but correlating these findings to objective measures, such as brain imaging or electrophysiology outcomes, allows speculations regarding the biological mechanisms and clinical relevance of these effects. Here, the reported correlations are mostly based on fMRI outcomes and measures of mood, especially depression. For example, lower brain activity during negative emotional stimulation was associated with improved mood and well-being in healthy individuals37 and IBS patients50 after probiotic but not placebo intake. Although not assessing correlations specifically, other studies in healthy cohorts allow similar interpretations regarding emotional regulation42,43 and cognition66 (the latter was excluded from this systematic review due to its non-randomised design). In depressed patients on active antidepressant treatment, changes in depressive symptom scores did not correlate with brain function during negative emotional stimulation53, but with functional and structural connectivity during resting state54. Not surprisingly, improved depression scores correlated with improved sleep patterns46. Furthermore, increases in waveform amplitude (measured by EEG) related to reward anticipation were negatively correlated with improved depression and anxiety scores56. The latter two, amongst the otherwise rather concise EEG studies, are the only ones reporting correlations, while most MRI studies, especially the more recent ones, employed a comprehensive design with a broad spectrum of outcome measures.

Hitherto, most studies assessed probiotic effects on brain health in healthy young-to-middle-aged populations. This may have been the case as studies in these populations offer easier recruitment and lower safety risks, as well as a more homogenous study group. Notably, several studies observed probiotic effects in healthy populations, supporting that the gut-brain axis is modifiable despite an expected ceiling effect with limited room for improvement. Yet, the generalisability of the results is only applicable to a healthy adult population. Ascone et al. argued for the use of a young adult population because of expected higher neuronal plasticity and hence a facilitated detection of any effects40. However, they reported one of the few studies with non-differential brain structure and function post-probiotic compared to placebo. Positive results in a healthy population related to decreased stress, improved sleep, or improved emotional regulation may be of great value for optimising health as a preventative measure. The current evidence, on the brain imaging or electrophysiology level, does not allow conclusions on whether probiotics are more effective in patient cohorts than in healthy subjects, but such a tendency is indicated on the level of symptomatology67. Hence, we call for more studies in compromised populations, including those with (subclinical) cognitive impairment, e.g., in an ageing population, or elevated stress levels (as e.g., mimicked by those studies testing cognition when buffered against stress32 or sleep in the setting of academic examination stress36) to confirm the subtle changes observed in mostly healthy cohorts. Importantly, to correct for factors leading to heterogeneity, larger sample sizes may be needed when studying patient cohorts. Finally, it is also time to conduct probiotic interventions with brain imaging or electrophysiology outcomes in conditions of disturbed gut-brain interactions, with IBS50 and depressed patients53,54,55,56 as pioneering examples. In IBS patients with comorbid depression and/or anxiety symptoms, Pinto-Sanchez et al. observed probiotic-induced changes in brain regions (previously associated with depression and anti-depressant treatment) whose activity correlated with gastrointestinal symptom scores50. Probiotic effects on major depression have so far been studied as an adjunctive to antidepressant treatment using brain imaging techniques53,54,55,56. The positive effect of probiotics on depressive symptomatology is moreover supported by a recent meta-analysis26. In children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, six-month multi-strain probiotic intake modified brain activity (as assessed by EEG) in conjunction with improved behavioural measures compared to placebo68. To note is that all included studies relied on randomisation, and none utilised typical covariates such as age, sex and others in their analyses.

The studies included in this review investigated a diversity of probiotics, which may contribute to observed potential probiotic effects on a broad spectrum. Mainly, probiotics of the Bifidobacterium genus and Lactobacillaceae family were able to modulate brain function. The diversity of results, however, does not enable us to draw conclusions on which probiotic species, strain or mixture may be the most effective. Interestingly, all EEG, MEG and fNIRS studies investigated single-strain products, while all rsfMRI and most task-based fMRI studies used multi-strain probiotics. All studies with multi-strain probiotic products, except one, had an intervention period of four weeks, whereas the intervention period for single-strain products ranged from four to 28 weeks. The optimal intervention length of probiotic interventions is not known. Schaub et al. motivate the duration of their intervention (31 days) with observed effects on behavioural outcomes53. Furthermore, Kelly et al. argue that anti-depressants do not have a strong effect in healthy subjects, plus they do need some onset time of approximately four weeks until effective, and the same might be applied regarding probiotic effects on brain function34. While four-week probiotic interventions have been shown to be sufficient to simultaneously modify the gut microbiota and brain function32,33, a change of the microbiota itself might not be necessary to see effects on brain health, as heat-inactivated L. gasseri has been shown to be effective in modulating brain function, as assessed by sleep EEG69,70 similar to the probiotics summarised in this review.

In/ex vivo studies investigating the underlying mechanisms could aid in understanding probiotic effects on the gut-brain axis beyond direct microbiota modulation. An interesting, but so far missing approach, is the identification of neurotransmitter levels by, e.g., magnetic resonance spectroscopy. The first approaches to assess brain tissue metabolites52 or blood metabolites51 are interesting and will provide invaluable information for the field. Furthermore, implementing follow-up of participants (as piloted by one of the EEG studies49), weeks after intervention, would be interesting to evaluate if probiotic effects can be long-lasting or how quickly they are declining. Also, the field is thus far lacking dose-response studies, which would be of great interest.

Several study products contained additional ingredients, including fructo-oligosaccharides49,52 and theanine45, with the potential to influence the gut microbiome, CNS, or immune system. In these cases, it is not possible to attribute the potential effects specifically to the probiotic compounds. However, this was not always transparently disclosed by the authors. Moreover, the importance of identical placebo and test products should be obvious, but this was not implemented by some of the investigated studies. Mental health research is susceptible to a strong placebo effect, which emphasises the importance of selecting an appropriate placebo even when applying objective brain outcome assessment methods71.

When studying probiotics using brain imaging or electrophysiology techniques, the absence of standardised procedures predominantly hampers our ability to draw conclusions from the cumulative evidence. However, human behaviour is formed by coordinated activities from large-scale networks, and studies of how the whole brain interplays are of interest72. The latter is likely one of the reasons why probiotic-induced alterations of brain function point towards similar conclusions. Studies were usually powered for their respective primary outcome, and as that is rarely a pure brain imaging or electrophysiology outcome, these investigations may often be underpowered.

We believe that this systematic review raises awareness and provides a summary that will be important for shaping protocols (for recommendations see Table 8) for this relatively new research field. Future probiotic and gut-brain axis research, using brain outcome assessment techniques in combination with in/ex vivo mechanistical assessments, could help clarify possible effects of probiotics on brain function beyond the potential preventive effects, inform clinical use and formulation of targeted products and interventions.

Methods

Protocols and registration

This systematic review was conducted following PRISMA guidelines, and initially submitted to PROSPERO on June 21, 2023. The registration record was automatically published after basic automated checks for eligibility and formally registered on July 2, 2023 under ID CRD42023438493.

Information sources and search strategy

A medical research librarian at Örebro University conducted a search in the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science. The basic structure of the search string was as follows: Probiotics AND (neuroimaging OR (imaging techniques AND brain) OR (electrophysiology techniques AND brain)). Relevant synonyms and subject headings for the search terms were used. The search was restricted to articles published in English. Conference abstracts were excluded from the Embase results. The complete search strategy can be found in Supplementary Note 1. The original and updated searches were conducted on June 20, 2023, January 9, 2024, and August 5, 2025, respectively. Search updates were performed without date restriction, and automatic duplicate removal was mainly handled by the Covidence tool. In addition to the described search strategy, a targeted search was performed in the clinical trials registers and references of the included studies to ensure that additional studies meeting the search criteria were not overlooked. In addition, the scientific network of the authors was consulted.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible full-text articles met the following criteria: randomised, placebo-controlled trials, participants aged 18 years and older, oral probiotic interventions (longer than one week; alone or in combination with other dietary interventions, e.g., prebiotics), and outcomes assessed with brain imaging or electrophysiology techniques.

Data management

The Covidence software was utilised for study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias and study quality assessment.

Study selection

Two authors (J.R., A.H.) independently screened all titles and abstracts of unique records, with discrepancies discussed among a team of three authors (J.R., A.H., and R.F.). The full text screening of eligible articles was performed by three authors (J.R., A.H., R.F.), with each article evaluated by at least two authors and discrepancies discussed among all three.

Data extraction

All authors participated in the data extraction and quality assessment, with at least two authors per included article and discrepancies were solved through discussion. The articles authored by J.R., A.H., and J.K. were extracted and evaluated by J.P.G.M. and R.F. to decrease biases. When the extraction matrix was complete for all included papers, the results were discussed between all authors, discrepancies identified and resolved.

Reporting of results

In accordance with the scope of this systematic review, all reported results focus on the comparisons between the probiotic and placebo intervention, despite some studies including other intervention groups (e.g., no-intervention controls) or assessing differences in population characteristics as well as data on experiment validation.

Risk of bias and study quality assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed with Covidence, in accordance with Higgins et al. in determining the scoring strategy73. Study quality of the individual studies was scored as Low (high risk of bias), High (low risk of bias), or Unclear using the following parameters: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias (including publication bias and commercial interests). Assessments were performed for each study by two authors of the study team, and discrepancies were resolved via discussion with the entire team. To further address potential publication bias, with e.g., negative findings not being reported/published due to commercial interests (potential funding bias), and since the variable outcome measures did not allow for traditional funnel plot estimations, we searched the database Clinicaltrials.gov for “probiotic” AND “brain” and screened the records in March 2024 and updated in August 2025. The results of these assessments of risk of bias and study quality can be found in Supplementary Notes 3 and 7, Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Tables 5 and 6. References 74,75,76,77,78,79,80 are solely cited in the Supplementary Information.

Data availability

This is a systematic review synthesising published work. No data have been generated for this work. All information is to be found in this article and its Supplementary Information file.

Code availability

No code was developed or used for this work.

References

Breit, S., Kupferberg, A., Rogler, G. & Hasler, G. Vagus nerve as modulator of the brain-gut axis in psychiatric and inflammatory disorders. Front. Psychiatry 9, 44 (2018).

Carabotti, M., Scirocco, A., Maselli, M. A. & Severi, C. The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann. Gastroenterol. 28, 203–209 (2015).

Jarrah, M., Tasabehji, D., Fraer, A. & Mokadem, M. Spinal afferent neurons: emerging regulators of energy balance and metabolism. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 17, 1479876.75 (2024).

Strandwitz, P. Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota. Brain Res. 1693, 128–133 (2018).

Agus, A., Planchais, J. & Sokol, H. Gut microbiota regulation of tryptophan metabolism in health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 23, 716–724 (2018).

Dalile, B., Van Oudenhove, L., Vervliet, B. & Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 461–478 (2019).

van de Wouw, M. et al. Short-chain fatty acids: microbial metabolites that alleviate stress-induced brain-gut axis alterations. J. Physiol. 596, 4923–4944 (2018).

Fung, T. C. The microbiota-immune axis as a central mediator of gut-brain communication. Neurobiol. Dis. 136, 104714 (2020).

Cryan, J. F. et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiol. Rev. 99, 1877–2013 (2019).

Janik, R. et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy reveals oral Lactobacillus promotion of increases in brain GABA, N-acetyl aspartate and glutamate. Neuroimage 125, 988–995 (2016).

Liu, S. et al. Gut microbiota regulates depression-like behavior in rats through the neuroendocrine-immune-mitochondrial pathway. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 16, 859–869 (2020).

Ong, I. M. et al. Gut microbiome populations are associated with structure-specific changes in white matter architecture. Transl. Psychiatry 8, 6 (2018).

Bharwani, A. et al. Structural & functional consequences of chronic psychosocial stress on the microbiome & host. Psychoneuroendocrinology 63, 217–227 (2016).

Hao, Z., Wang, W., Guo, R. & Liu, H. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (ATCC 27766) has preventive and therapeutic effects on chronic unpredictable mild stress-induced depression-like and anxiety-like behavior in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology 104, 132–142 (2019).

Kelly, J. R. et al. Transferring the blues: depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat. J. Psychiatr. Res 82, 109–118 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Similar fecal microbiota signatures in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and patients with depression. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 1602–1611 e5 (2016).

Koloski, N. A., Jones, M. & Talley, N. J. Evidence that independent gut-to-brain and brain-to-gut pathways operate in the irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia: a 1-year population-based prospective study. Aliment Pharm. Ther. 44, 592–600 (2016).

Jacobs, J. P. et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for irritable bowel syndrome induces bidirectional alterations in the brain-gut-microbiome axis associated with gastrointestinal symptom improvement. Microbiome 9, 236 (2021).

Drossman, D. A. & Hasler, W. L. Rome IV-functional gi disorders: disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology 150, 1257–1261 (2016).

Ansari, F. et al. The role of probiotics and prebiotics in modulating of the gut-brain axis. Front. Nutr. 10, 1173660 (2023).

Hill, C. et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 506–514 (2014).

Medawar, E. et al. Prebiotic diet changes neural correlates of food decision-making in overweight adults: a randomised controlled within-subject cross-over trial. Gut 73, 298–310 (2024).

Groeger, D. et al. Interactions between symptoms and psychological status in irritable bowel syndrome: an exploratory study of the impact of a probiotic combination. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 35, e14477 (2023).

Le Morvan de Sequeira C., Hengstberger C., Enck P., Mack I. Effect of probiotics on psychiatric symptoms and central nervous system functions in human health and disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 14, 621 (2022)

Hofmeister, M. et al. The effect of interventions targeting gut microbiota on depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ Open 9, E1195–E1204 (2021).

Zhang, Q. et al. Effect of prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics on depression: results from a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 23, 477 (2023).

Koley, B. & Dey, D. An ensemble system for automatic sleep stage classification using single channel EEG signal. Comput. Biol. Med 42, 1186–1195 (2012).

Lee, M. H., Smyser, C. D. & Shimony, J. S. Resting-state fMRI: a review of methods and clinical applications. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 34, 1866–1872 (2013).

Grady, C. L., McIntosh, A. R. & Craik, F. I. Task-related activity in prefrontal cortex and its relation to recognition memory performance in young and old adults. Neuropsychologia 43, 1466–1481 (2005).

Perlman, S. B. & Pelphrey, K. A. Developing connections for affective regulation: age-related changes in emotional brain connectivity. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 108, 607–620 (2011).

Tillisch, K. et al. Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. Gastroenterology 144, 1394–1401 (2013).

Papalini, S. et al. Stress matters: Randomized controlled trial on the effect of probiotics on neurocognition. Neurobiol. Stress 10, 100141 (2019).

Bloemendaal, M. et al. Probiotics-induced changes in gut microbial composition and its effects on cognitive performance after stress: exploratory analyses. Transl. Psychiatry 11, 300 (2021).

Kelly, J. R. et al. Lost in translation? The potential psychobiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus (JB-1) fails to modulate stress or cognitive performance in healthy male subjects. Brain Behav. Immun. 61, 50–59 (2017).

Adikari, A., Appukutty, M. & Kuan, G. Effects of daily probiotics supplementation on anxiety induced physiological parameters among competitive football players. Nutrients 12, 1920 (2020).

Takada, M. et al. Beneficial effects of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on academic stress-induced sleep disturbance in healthy adults: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Benef. Microbes 8, 153–162 (2017).

Bagga, D. et al. Probiotics drive gut microbiome triggering emotional brain signatures. Gut Microbes 9, 486–496 (2018).

Bagga, D. et al. Influence of 4-week multi-strain probiotic administration on resting-state functional connectivity in healthy volunteers. Eur. J. Nutr. 58, 1821–1827 (2019).

Wang, H., Braun, C., Murphy, E. F. & Enck, P. Bifidobacterium longum 1714 strain modulates brain activity of healthy volunteers during social stress. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 114, 1152–1162 (2019).

Ascone L., Garcia Forlim C., Gallinat J., Kuhn S. Effects of a multi-strain probiotic on hippocampal structure and function, cognition, and emotional well-being in healthy individuals: a double-blind randomised-controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 1–11 (2022)

Edebol Carlman, H. M. T. et al. Probiotic mixture containing lactobacillus helveticus, bifidobacterium longum and lactiplantibacillus plantarum affects brain responses to an arithmetic stress task in healthy subjects: a randomised clinical trial and proof-of-concept study. Nutrients 14, 1329 (2022).

Rode, J. et al. Probiotic mixture containing lactobacillus helveticus, bifidobacterium longum and lactiplantibacillus plantarum affects brain responses toward an emotional task in healthy subjects: a randomized clinical trial. Front Nutr. 9, 827182 (2022).

Rode, J. et al. Multi-strain probiotic mixture affects brain morphology and resting state brain function in healthy subjects: an RCT. Cells 11, 2922 (2022).

Mutoh, N. et al. Bifidobacterium breve M-16V regulates the autonomic nervous system via the intestinal environment: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Behav. Brain Res. 460, 114820 (2024).

Nakagawa M. et al. Effects of lactic acid bacteria-containing foods on the quality of sleep: a placebo-controlled, double-blinded, randomized crossover study. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 8, 12 (2018).

Ho, Y. T., Tsai, Y. C., Kuo, T. B. J. & Yang, C. C. H. Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 on depressive symptoms and sleep quality in self-reported insomniacs: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Nutrients 13, 2820 (2021).

Kikuchi-Hayakawa, H. et al. Effects of lacticaseibacillus paracasei strain shirota on daytime performance in healthy office workers: a double-blind, randomized, crossover, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients 15, 5119 (2023).

Asaoka, D. et al. Effect of probiotic bifidobacterium breve in improving cognitive function and preventing brain atrophy in older patients with suspected mild cognitive impairment: results of a 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Alzheimers Dis. 88, 75–95 (2022).

Malaguarnera, M. et al. Bifidobacterium longum with fructo-oligosaccharide (FOS) treatment in minimal hepatic encephalopathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 52, 3259–3265 (2007).

Pinto-Sanchez, M. I. et al. Probiotic bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 reduces depression scores and alters brain activity: a pilot study in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 153, 448–459 e8 (2017).

Martin, F. P. et al. Metabolome-associated psychological comorbidities improvement in irritable bowel syndrome patients receiving a probiotic. Gut Microbes 16, 2347715 (2024).

Ranisavljev, M. et al. The effects of 3-month supplementation with synbiotic on patient-reported outcomes, exercise tolerance, and brain and muscle metabolism in adult patients with post-COVID-19 chronic fatigue syndrome (STOP-FATIGUE): a randomized Placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 64, 28 (2024).

Schaub, A. C. et al. Clinical, gut microbial and neural effects of a probiotic add-on therapy in depressed patients: a randomized controlled trial. Transl. Psychiatry 12, 227 (2022).

Yamanbaeva, G. et al. Effects of a probiotic add-on treatment on fronto-limbic brain structure, function, and perfusion in depression: secondary neuroimaging findings of a randomized controlled trial. J. Affect Disord. 324, 529–538 (2023).

Schneider, E. et al. Effect of short-term, high-dose probiotic supplementation on cognition, related brain functions and BDNF in patients with depression: a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 48, E23–E33 (2023).

Li, D. X. et al. Efficacy of Pediococcus acidilactici CCFM6432 in alleviating anhedonia in major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. World J. Psychiatry 15, 105249 (2025).

Ranisavljev, M. et al. Correction: The effects of 3-month supplementation with synbiotic on patient-reported outcomes, exercise tolerance, and brain and muscle metabolism in adult patients with post-COVID-19 chronic fatigue syndrome (STOP-FATIGUE): a randomized Placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 64, 80 (2025).

Campbell, I. G. EEG recording and analysis for sleep research. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. Chapter 10, Unit10 2 (2009).

Lopes da Silva, F. EEG and MEG: relevance to neuroscience. Neuron 80, 1112–1128 (2013).

Crocetta, A. et al. From gut to brain: unveiling probiotic effects through a neuroimaging perspective-a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front Nutr. 11, 1446854 (2024).

Gray, J. R., Braver, T. S. & Raichle, M. E. Integration of emotion and cognition in the lateral prefrontal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 4115–4120 (2002).

Ochsner, K. N., Bunge, S. A., Gross, J. J. & Gabrieli, J. D. Rethinking feelings: an FMRI study of the cognitive regulation of emotion. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 14, 1215–1229 (2002).

Kohn, N. et al. Multivariate associative patterns between the gut microbiota and large-scale brain network connectivity. Gut Microbes 13, 2006586 (2021).

Cai, H. et al. Large-scale functional network connectivity mediate the associations of gut microbiota with sleep quality and executive functions. Hum. Brain Mapp. 42, 3088–3101 (2021).

Mulder, D., Aarts, E., Arias Vasquez, A. & Bloemendaal, M. A systematic review exploring the association between the human gut microbiota and brain connectivity in health and disease. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 5037–5061 (2023).

Allen, A. P. et al. Bifidobacterium longum 1714 as a translational psychobiotic: modulation of stress, electrophysiology and neurocognition in healthy volunteers. Transl. Psychiatry 6, e939 (2016).

He, J. et al. Effect of probiotic supplementation on cognition and depressive symptoms in patients with depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 102, e36005 (2023).

Billeci, L. et al. A randomized controlled trial into the effects of probiotics on electroencephalography in preschoolers with autism. Autism 27, 117–132 (2023).

Nishida, K. et al. Health benefits of Lactobacillus gasseri CP2305 tablets in young adults exposed to chronic stress: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Nutrients 11, 1859 (2019).

Nishida, K. et al. Daily administration of paraprobiotic CP2305 ameliorates chronic stress-associated symptoms in Japanese medical students. J. Funct. Foods 36, 112–121 (2017).

Wager, T. D. & Atlas, L. Y. The neuroscience of placebo effects: connecting context, learning and health. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 403–418 (2015).

Menon, V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 483–506 (2011).

Higgins J. P. et al. Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 205–228. (2019)

Karakula-Juchnowicz, H. et al. The study evaluating the effect of probiotic supplementation on the mental status, inflammation, and intestinal barrier in major depressive disorder patients using gluten-free or gluten-containing diet (SANGUT study): a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled clinical study protocol. Nutr. J. 18, 50 (2019).

Wallace, C. J. K., Foster, J. A., Soares, C. N. & Milev, R. V. The effects of probiotics on symptoms of depression: protocol for a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychobiology 79, 108–116 (2020).

Cardelo, M. P. et al. Effect of the Mediterranean diet and probiotic supplementation in the management of mild cognitive impairment: rationale, methods, and baseline characteristics. Front. Nutr. 9, 1037842 (2022).

Hsu, Y. C. et al. Efficacy of probiotic supplements on brain-derived neurotrophic factor, inflammatory biomarkers, oxidative stress and cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia: a 12-week randomized, double-blind active-controlled study. Nutrients 16, 16 (2023).

Nikolova, V. L., Cleare, A. J., Young, A. H. & Stone, J. M. Acceptability, tolerability, and estimates of putative treatment effects of probiotics as adjunctive treatment in patients with depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 80, 842–847 (2023).

Nikolova, V. L., Cleare, A. J., Young, A. H. & Stone, J. M. Exploring the mechanisms of action of probiotics in depression: results from a randomized controlled pilot trial. J. Affect Disord. 376, 241–250 (2025).

Morales-Torres, R. et al. Psychobiotic effects on anxiety are modulated by lifestyle behaviors: a randomized placebo-controlled trial on healthy adults. Nutrients 15, 1706 (2023).

Ascone L., Garcia Forlim C., Gallinat J., Kuhn S. Effects of a multi-strain probiotic on hippocampal structure and function, cognition, and emotional well-being in healthy individuals: a double-blind randomized-controlled trial - CORRIGENDUM. Psychol. Med. 1–11 (2022).

Zheng, J. et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: d.0escription of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 70, 2782–2858 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Liz Holmgren and Elias Olsson, librarians at Örebro University Library. No funder was involved in this work.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Örebro University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H., R.F., J.K., J.P.G.M., J.R.: conceptualisation and validation; A.H., J.R.: methodology; A.H., A.A., R.F., J.K., J.P.G.M., J.R.: investigation, writing–original draft, writing–review & editing; JR: project administration and supervision; A.H., A.A., J.R.: visualisation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Richard Forsgård is an employee of Häme University of Applied Sciences. The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hutchinson, A.N., Antonsson, A.E., Forsgård, R.A. et al. The effects of oral probiotic intervention on brain structure and function in human adults: a systematic review. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 12, 6 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00872-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00872-x