Abstract

This real-world, multicenter study evaluated trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) in 64 patients with HR-negative, HER2-low metastatic breast cancer between May 2022 and May 2025. The median lines of therapy were 3 (range 1–7). The objective response rate (ORR) was 35.9%, and the disease control rate was 75%. Median real-world progression-free survival (rwPFS) and overall survival were 5.0 months and 14.9 months, respectively. Multivariate analysis identified brain metastases and prior Trop-2 ADC treatment as independent predictors of shorter rwPFS. The most common adverse events were nausea (71.9%), fatigue (39.1%), anorexia (31.3%), and neutropenia (31.3%). Grade 3/4 adverse events were primarily neutropenia (9.4%), thrombocytopenia (7.8%), and nausea (3.1%). Despite lower ORRs in patients with BRCA1 mutations or MYC amplifications, the differences were not statistically significant. This study confirms the clinical efficacy and manageable safety profile of T-DXd in this population, identifying high-risk subgroups and potential resistance biomarkers to inform treatment decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

HER2-low breast cancer (BC), defined by an immunohistochemical (IHC) score of 1+ or 2+ in the absence of HER2 gene amplification, has emerged as a distinct clinical entity following the demonstrated efficacy of trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd)1,2. This subtype is present in approximately 50–60% of hormone receptor (HR)-positive BC and about 12–20% of HR-negative cases3,4, representing a heterogenous population with diverse prognostic outcomes and treatment response.

The landmark DESTINY-Breast 04 (DB-04) trial, the first phase III trial to establish efficacy of T-DXd in HER2-low metastatic breast cancer (mBC), enrolled 557 patients who had received one to two prior lines of chemotherapy for metastatic disease. T-DXd significantly improved outcomes compared with physician’s choice treatment, with median progression-free survival (PFS) of 9.9 months vs. 5.1 months (hazard ratio (HR): 0.50, P < 0.001), and median overall survival (OS) of 23.4 months vs. 16.8 months (HR: 0.64, P = 0.001)5. These findings were further extended by the DB-06 trial, which also demonstrated survival benefits with T-DXd in both HER2-low and HER2-ultralow (IHC zero with any membrane staining) mBC populations6.

However, both trials included limited representation of HR-negative HER2-low mBC patients. DB-04 trial enrolled only 58 HR-negative patients, with 40 receiving T-DXd, while DB-06 excluded this subgroup entirely5,6. This underrepresentation has left a critical evidence gap regarding the efficacy of T-DXd in HR-negative HER2-low mBC, particularly relative to other treatment options such as the anti-trop 2 antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) Sacituzumab govitecan (SG)7.

To address this unmet need, we conducted a multicenter real-world study to evaluate the clinical performance of T-DXd in HR-negative HER2-low mBC.

Results

Patient characteristics

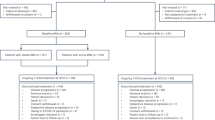

Between May 2022 and May 2025, a total of 64 patients were included in this study. The patient selection process was detailed in Supplementary Fig. 1. Baseline characteristics were summarized in Table 1. All patients were female, with a median age of 47 years (range 30–80). Of these, 34 (53.1%) had primary HR-negative disease, while 30 (46.9%) had converted from HR-positive to HR-negative status. Fifty-two (81.2%) patients presented with primary HER2-low BC, and 12 (18.8%) had converted from HER2-zero to HER2-low disease. HER2 expression levels were equally distributed, with 50% of patients showing HER2 1+ and 50% HER2 2+. Visceral metastases were presented in 47 (73.4%) patients, including liver metastases in 29 (45.3%), lung metastases in 27 (42.2%), and brain metastases (BM) in 11 (17.2%). T-DXd was administered as first- or second-line in 21 (32.8%) patients, and third-line or later treatment in 43 (67.2%) patients. The median number of lines of therapy for metastatic disease was 3 (range 1–7). Thirteen (20.3%) patients had progressed after endocrine therapy (ET) and CDK4/6 inhibitors during an earlier HR-positive disease phase. Ten (15.6%) patients had received prior Trop-2 ADC therapy.

Efficacy

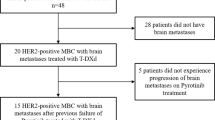

Up to May 2025, the median number of T-DXd cycles administered was 6 (range 2–25). Treatment was discontinued in 53 (82.8%) patients, primarily due to disease progression (n = 50), followed by grade 3/4 AEs (n = 2), and loss to follow-up (n = 1) (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2a). A total of 31 (48.4%) deaths were recorded (Supplementary Fig. 2b). In the overall population, 23 (35.9%) patients achieved PR, 25 (39.1%) had SD, and 16 (25%) experienced PD, resulting an ORR of 35.9% and a DCR of 75% (Table 2). ORR and DCR were higher in patients with HER2 IHC 2+ compared to IHC 1+ (ORR: 40.6% vs. 31.2%; DCR: 84.4% vs. 65.6%). Among the 11 patients with BM, ORR and DCR were 18.2% and 63.6%. None of the 10 patients with prior Trop-2 ADC exposure achieved a PR, and the DCR in this subgroup was 50% (Supplementary Table 2).

After a median follow-up of 19.5 months (95% CI: 14.5–21.5 months), the median rwPFS and OS in the whole cohort were 5.0 and 14.9 months, respectively (Fig. 1). Subgroup analysis showed patients with HER2 2+ had significantly longer median rwPFS than those with HER2 1+ (6.0 vs. 3.9 months; HR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.31–0.96, P = 0.020), though the OS did not differ significantly (18.1 vs. 14.0 months; HR. 0.65, 95% CI: 0.32–1.33, P = 0.220) (Fig. 2a, b, Supplementary Table 2). Patients with BM had shorter rwPFS (3.6 vs. 5.6 months; HR: 2.57, 95% CI: 0.97–6.82, P = 0.004) and OS (8.6 vs. 15.7 months; HR: 2.44, 95% CI: 0.78–7.65, P = 0.030) compared to those without BM (Fig. 2c, d, Supplementary Table 2). Similarly, prior exposure to Trop-2 ADC was associated with inferior rwPFS (3.1 vs. 5.5 months; HR: 2.51, 95% CI: 0.91–6.93, P = 0.020) and OS (11.1 vs. 15.7 months; HR: 2.46, 95% CI: 0.78–7.73, P = 0.030) compared to Trop-2 ADC-naïve patients (Fig. 2e, f, Supplementary Table 2).

The Kaplan-Meier curve for rwPFS (a) and OS (b) of patients with HER2 2+ and HER2 1+; The Kaplan-Meier curve for rwPFS (c) and OS (d) of brain metastasis patients; The Kaplan-Meier curve for rwPFS (e) and OS (f) of trop 2 ADC-treated and without trop 2 ADC-treated patients. rwPFS, real-world progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; ADC, antibody-drug conjugate.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of rwPFS and OS

Univariate analysis identified several factors associated with poor rwPFS, including BM, HER2 1+, PD-L1 CPS ≥ 1, prior Trop-2 ADC exposure. Multivariate analysis confirmed that BM (HR: 2.46, 95% CI: 1.15–5.29, P = 0.021) and prior Trop-2 ADC treatment (HR: 2.79, 95% CI: 1.28–6.08, P = 0.010) were independent negative prognostic factors for rwPFS (Fig. 3). Both factors were also significantly associated with worse OS in univariate and multivariate analyses (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Potential biomarkers from next-generation sequencing

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed on tumor samples from 28 (43.8%) patients. An oncoplot summarizing genetic alterations and corresponding treatment response was shown in Fig. 4. The most frequently mutated genes were TP53 (86%), PIK3CA (32%), MYC (21%) and PTEN (18%), respectively. BRCA1 mutations were detected in 7 (25%) patients, including 5 germline mutations and 2 somatic mutations. The ORRs were comparable between patients with and without TP53 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR (PAM) pathway mutations. Meanwhile, compared with patients without these alterations, those with MYC amplifications or BRCA1 mutations showed numerically lower, but statistically insignificant, with ORRs of 16.7% and 14.3%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Safety

Treatment-related AEs were summarized in Table 3. Among the 64 patients, 93.8% experienced at least one AE, and grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 14.1%. The most common AEs of any grade were nausea (71.9%), fatigue (39.1%), anorexia (31.3%), neutropenia (31.3%), anemia (29.7%), vomiting (26.6%), and thrombocytopenia (17.2%). The most common grade 3/4 AEs were neutropenia (9.4%), thrombocytopenia (7.8%), nausea (3.1%), anorexia (3.1%), anemia (3.1%), vomiting (3.1%). Drug-related interstitial lung disease (ILD) occurred in three patients (4.7%), including one case of grade 3 ILD that required hospitalization for steroid treatment. Dose reduction was required in 5 (10.9%) patients due to thrombocytopenia (n = 3), vomiting (n = 1), and neutropenia (n = 1). Dose delay occurred in 10 (15.6%) patients (Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

This study provides the first real-world evidence specifically evaluating the efficacy and safety of T-DXd in patients with HR-negative, HER2-low mBC. Compared to HR-negative subgroup in the DB-04 trial, our cohort included a higher proportion of heavily pretreated patients (over two-thirds receiving third-line or later therapy), more cases with BM, and individuals with prior exposure to ADCs. Despite these less favorable baseline characteristics, T-DXd monotherapy demonstrated clinically meaningful outcomes, with an ORR of 35.9%, a median rwPFS of 5.0 months, and a median OS of 14.9 months. Although these results are somewhat lower than those reported in the DB-04 trial (ORR of 50%, median PFS of 8.5 months, and median OS of 18.2 months in HR-negative subgroup)5, they remain encouraging given the more challenging clinical profile of our real-world population.

In contrast to DB-04 and DAISY trials, which reported comparable efficacy between HER2 2+ and 1+ subgroups5,8, our analysis showed significantly improved outcomes in patients with HER2 2+ expression, including higher ORR and longer rwPFS. This observation is supported by another real-world study, which also indicated superior T-DXd efficacy in HER2 2+/FISH-negative patients compared to those with HER2 1+ disease9. A similar trend has also been observed with the anti-HER2 ADC RC48, which demonstrated enhanced activity in HER2 2+ tumors relative to HER2 1+ cases10. Several biological mechanisms may explain this differential response. First, HER2 2+ tumors express 10–50 times more surface HER2 receptors than HER2 1+ tumors11,12, which may facilitate more efficient internalization of ADC and delivery of the cytotoxic payload. Second, HER2 1+ tumors often exhibit greater spatial heterogeneity13,14,15, which may compromise uniform drug distribution and target engagement. Third, current HER2 IHC assessment is subject to interobserver variability, with reported concordance rates as low as 18–26% in distinguishing between HER2 zero from HER2 1+16,17. The adoption of quantitative HER2 scoring methods may improve patient stratification and predictive accuracy for ADC efficacy in the future.

Additional clinical factors associated with poorer T-DXd outcomes included the presence of BM and prior ADC treatment. Among the 10 patients pretreated with SG, none achieved an objective response, and this subgroup exhibited significantly shorter median rwPFS and OS compared with ADC-naïve patients, consistent with prior reports18,19. Given the structural similarities in the payloads of SG and T-DXd, potential cross-resistance mechanism may involve altered intracellular trafficking, enhanced lysosomal degradation, upregulation of drug efflux pumps, or activation of alternative survival and DNA repair pathway20,21. In addition, patients with BM also experienced significantly inferior rwPFS and OS compared to those without BM, aligning with previous clinical observations22,23.

NGS analysis performed in 28 patients showed comparable ORR between those with and without alterations in the PAM pathway, consistent with biomarker findings from the DB-06 trial presented at American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 202524. Although numerical trends suggesting lower ORRs in patients with BRCA1 mutations or MYC amplifications, these differences were not statistically significant, likely due to the limited sample size, and should therefore be interpreted with caution.

The safety profile of T-DXd in this cohort was consistent with previous studies, with no new safety signals observed5,25,26. The most common AEs were gastrointestinal, particularly nausea, which affected over 70% of patients. This occurred despite the majority of patients receiving triple-agent antiemetic prophylaxis (typically comprising a 5-HT3 antagonist, an NK-1 antagonist, and dexamethasone). The recently published landmark ERICA study demonstrated that adding olanzapine to a standard triple regimen achieved a nearly 20% reduction in the incidence of nausea27. Therefore, adopting this enhanced prophylactic strategy could be key to optimizing treatment continuity and patient compliance with T-DXd. Other toxicities were manageable: hematological events necessitated supportive care and occasional dose modifications, while the incidence of ILD was favorably low28, with the single grade 3 event responding to steroids.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. Its retrospective design introduces potential biases in data collection and patient selection. The sample size was limited, particularly in key subgroups such as those with prior ADC exposure or presence of BM, which may affect the generalizability and statistical power of the findings. The lack of centralized pathology review for HER2 and HR status may also contribute to assessment variability. Moreover, the inclusion of only Chinese patients may limit the extrapolation of results to other ethnic populations. Heterogeneity in treatment patterns across participating centers could have additionally influenced outcomes. Future prospective, multicenter studies with larger cohorts, longer follow-up, and centralized biomarker validation are warranted to confirm these findings.

In summary, this real-world analysis supports T-DXd as an effective treatment option for patients with HR-negative HER2-low mBC, extending evidence from pivotal trials to a more heterogeneous clinical setting. Larger prospective studies incorporating comprehensive biomarker evaluation are needed to validate these results across diverse populations, identify reliable predictive biomarkers and optimize treatment sequencing strategies for this distinct molecular subtype.

Methods

Patient selection and enrollment criteria

We conducted a multicenter, retrospective cohort study of patients with HR-negative, HER2-low mBC who were treated with T-DXd across four participating institutions: Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (SYSUCC), the Cancer Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University, Macau Kiang Wu Hospital, and Foshan First People’s Hospital. The study period spanned from May 2022 to May 2025. Inclusion criteria were (1) histologically confirmed mBC; (2) received at least one cycle of T-DXd treatment; (3) confirmation of HR-negative and HER2-low status on the most recent tumor biopsy prior to T-DXd initiation (HR-negative defined as estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor were <1% by IHC, and HER2-low expression defined as HER2 IHC 1+ or 2+/ISH-negative); and (4) presence of measurable metastatic disease with available response assessments. Clinical data were systematically extracted from electronic medical records within each hospital’s information system. Collected variables included demographic information, tumor clinicopathological characteristics, treatment history, laboratory results, and radiographic assessment reports. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (B2025-180-01) and the requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective design. The study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Treatment and response assessment

T-DXd was administered intravenously on day 1 of 21-day cycle. Treatment continued until disease progression, intolerable toxicity, or any other reasons necessitating discontinuation. Treatment response was evaluated by investigators based on radiographic assessments conducted in real-world clinical practice. All patients underwent computed tomography (CT) scan, and Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 criteria were applied retrospectively as a study purpose to evaluate the response of treatment. ORR was defined as the proportion of evaluable patients achieving a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) as their best objective tumor response. DCR included patients with CR, PR, or stable disease (SD). Real-world PFS (rwPFS) was measured from the start of T-DXd treatment to the first documented disease progression (clinical or radiographic) or death from any cause. OS was defined as the time from T-DXd initiation to death from any cause or the last follow-up. Adverse events (AEs) were graded according to the National Cancer Institute-Common Terminology Criteria (NCI-CTCAE) version 5.0.

Next-generation sequencing

Genomic profiling data were obtained from clinical notes and molecular sequencing reports. Hybrid capture-based targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed using OncoScreen Plus panel (OncoScreenPlus™, Burning Rock, Guangzhou, China) which covers the whole exons of 312 genes and hotspot mutations of 208 genes29. Genomic DNA was extracted and sheared from archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples along with matched normal tissues. Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from plasma was analyzed alongside matched germline DNA from whole blood to identify somatic alterations. Libraries were constructed with a median coverage depth >500×. Somatic variant analysis included single-nucleotide variants, small insertions and deletions, copy number alterations, and gene fusions/rearrangements. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) was calculated as the number of nonsynonymous somatic mutations (including SNVs and Indels) per megabase (Mb) of the sequenced coding region.

Statistics analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 5.01 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) and R version 4.2.2 (The R Project for Statistical Computing, www.r-project.org). Baseline characteristics, effectiveness and safety data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Time-to-event endpoints (rwPFS and OS) were estimated using Kaplan–Meier method, with median values and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) reported. Hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated from Cox regression models. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to evaluate prognostic factors. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available to protect patient privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Prat, A. et al. An overview of clinical development of agents for metastatic or advanced breast cancer without ERBB2 amplification (HER2-Low). JAMA Oncol. 8, 1676–1687 (2022).

Franchina, M. et al. Low and ultra-low HER2 in human breast cancer: an effort to define new neoplastic subtypes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 12795 (2023).

Schettini, F. et al. Clinical, pathological, and PAM50 gene expression features of HER2-low breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 7, 1 (2021).

You, S. et al. Clinicopathological characteristics, evolution, treatment pattern and outcomes of hormone-receptor-positive/HER2-low metastatic breast cancer. Front Endocrinol. 14, 1270453 (2023).

Modi, S. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-low advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 9–20 (2022).

Bardia, A. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan after endocrine therapy in metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 2110–2122 (2024).

Bardia, A. et al. Sacituzumab govitecan in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1529–1541 (2021).

Mosele, F. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in metastatic breast cancer with variable HER2 expression: the phase 2 DAISY trial. Nat. Med. 29, 2110–2120 (2023).

Wu, S. et al. Real-world efficacy and safety of trastuzumab deruxtecan in heavily pre-treated HER2-low metastatic breast cancer with distinct IHC statuses: evidence from a Chinese population. ESMO Asia. Poster, 52P (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Disitamab vedotin, a HER2-directed antibody-drug conjugate, in patients with HER2-overexpression and HER2-low advanced breast cancer: a phase I/Ib study. Cancer Commun. 44, 833–851 (2024).

Wolff, A. C. et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: ASCO-College of American Pathologists Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 3867–3872 (2023).

Moutafi, M. et al. Quantitative measurement of HER2 expression to subclassify ERBB2 unamplified breast cancer. Lab Invest 102, 1101–1108 (2022).

Ogitani, Y. et al. Bystander killing effect of DS-8201a, a novel anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 antibody-drug conjugate, in tumors with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterogeneity. Cancer Sci. 107, 1039–1046 (2016).

D’Angelo, F. et al. Temporal and spatial heterogeneity of HER2 status in metastatic colorectal cancer. Diagn. Pathol. 19, 88 (2024).

Geukens, T. et al. Intra-patient and inter-metastasis heterogeneity of HER2-low status in metastatic breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 188, 152–160 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Correlation of HER2 protein level with mRNA level quantified by RNAscope in breast cancer. Mod. Pathol. 37, 100408 (2024).

Fernandez, A. I. et al. Examination of low ERBB2 protein expression in breast cancer tissue. JAMA Oncol. 8, 1 (2022).

Poumeaud, F. et al. Efficacy of administration sequence: Sacituzumab Govitecan and Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in HER2-low metastatic breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 131, 702–708 (2024).

Huppert, L. A. et al. Multicenter retrospective cohort study of the sequential use of the antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) and sacituzumab govitecan (SG) in patients with HER2-low metastatic breast cancer (MBC). NPJ Breast Cancer 11, 34 (2025).

Chen, Y. F., Xu, Y. Y., Shao, Z. M. & Yu, K. D. Resistance to antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer: mechanisms and solutions. Cancer Commun. 43, 297–337 (2023).

Coates, J. T. et al. Parallel genomic alterations of antigen and payload targets mediate polyclonal acquired clinical resistance to sacituzumab govitecan in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 11, 2436–2445 (2021).

Vaz Batista, M. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with previously treated HER2-low advanced breast cancer and active brain metastases: the DEBBRAH trial. ESMO Open 9, 103699 (2024).

Vaz Batista, M. et al. The DEBBRAH trial: trastuzumab deruxtecan in HER2-positive and HER2-low breast cancer patients with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Med 6, 100502 (2025).

Dent, R. A. et al. Exploratory biomarker analysis of trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) vs physician’s choice of chemotherapy (TPC) in HER2-low ultralow, hormone receptor-positive (HR+) metastatic breast cancer (mBC) in DESTINY-Breast06 (DB-06). ASCO Abstract 1013 (2025).

Cortés, J. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan versus trastuzumab emtansine for breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 1143–1154 (2022).

André, F. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan versus treatment of physician’s choice in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (DESTINY-Breast02): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet 401, 1773–1785 (2023).

Sakai, H. et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II study of olanzapine-based prophylactic antiemetic therapy for delayed and persistent nausea and vomiting in patients with HER2-positive or HER2-low breast cancer treated with trastuzumab deruxtecan: ERICA study (WJOG14320B). Ann. Oncol. 36, 31–42 (2025).

Rugo, H. S. et al. Optimizing treatment management of trastuzumab deruxtecan in clinical practice of breast cancer. ESMO Open 7, 100553 (2022).

Wang, M. et al. Concordance study of a 520-gene next-generation sequencing-based genomic profiling assay of tissue and plasma samples. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 26, 309–322 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2021YFE0206300), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773279, 82073391).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.N. and D.W.: Writing—original draft, data curation, formal analysis, visualization. S.D. and Q.Z.: Conceptualization, resources. W.X., R.H., and Y.S.: Methodology, data curation. Z.Y. and J.H.: Resources. F.X., L.L., Y.C., and D.P.: Data curation, validation. X.A. and S.W.: Conceptualization, investigation, supervision, writing—reviewing and editing. All authors read and approved this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ni, M., Wang, D., Dun, S. et al. Real-world outcomes of trastuzumab deruxtecan in HR-negative HER2-low metastatic breast cancer. npj Breast Cancer 11, 123 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00841-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00841-9