Abstract

Despite improvements in surgical techniques, advances in delivery of radiation therapy, and development of therapies with central nervous system (CNS) activity, the presence of CNS metastases from breast cancer is frequently associated with a poor prognosis. In 2023, the leadership of the Breast International Group and National Cancer Institute’s National Clinical Trials Network convened a CNS working group to identify key challenges and discuss ways that international collaborations could push forward progress in the field. This review reflects initial discussions of the working group and addresses (1) the possible role of screening for CNS metastases, (2) optimal sequencing of local and systemic therapies among patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive CNS metastases, (3) management of leptomeningeal disease, and (4) the importance of developing innovative clinical trials for treatment and prevention of CNS metastases across breast cancer subtypes that is informed by preclinical data/basic science, with seamless knowledge translation to allow for rapid clinical adoption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Historically, the development of central nervous system (CNS) metastases among patients with breast cancer was associated with a very poor prognosis, with treatment options limited to surgical resection in highly selected patients, whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT), and supportive care. Over the past two decades, improvements in surgical techniques, advances in the delivery of radiation therapy, and the development of more effective CNS-active systemic therapies have resulted in meaningful improvements in quality-of-life (QoL) and survival in a subset of patients. However, many patients still have a poor prognosis, and even those patients with an initial response to treatment will almost invariably eventually experience disease progression. More research is required to further advance progress in this area of highly unmet need.

In the field of local therapy, stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) has emerged as a standard of care for patients with limited CNS metastases, with reduced impact on neurocognition and QoL compared to WBRT, though with higher rates of distant intracranial progression1,2,3,4. The use of cavity radiation instead of WBRT after surgical resection of CNS metastases5,6,7,8,9, or even SRS prior to surgery10,11,12,13, as well as hippocampal avoidance and use of memantine when WBRT is required14, have also reduced toxicity and improved patients’ QoL.

The advent of several drugs demonstrating meaningful CNS activity among patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+ve) breast cancer has heralded important new options for patients. For the first time, systemic therapies have shown sufficient efficacy among patients with active (previously untreated or previously treated and progressing) HER2+ve CNS metastases to allow for concurrent treatment of both intra- and extra-cranial disease and to delay the need for local therapy to the brain in some cases15,16,17,18,19,20, thus delaying its potential neurocognitive complications.

A major limiting factor impeding progress has been the historical exclusion of patients with CNS metastases from most clinical trials and a lack of standardization around reporting of CNS metastasis specific outcomes or toxicity. Greater inclusion of patients with CNS metastases in clinical trials, as recommended in the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and Friends of Cancer Research Joint Research Statement21 and FDA guidance to industry22, is critical to accelerating progress in the field. Unfortunately, in reality, though eligibility criteria in ongoing trials have changed to some extent, the majority of trials still exclude patients with active brain metastases, and virtually all exclude patients with any history of leptomeningeal disease (LMD) 23,24.

With these therapeutic advances have come several open questions and challenges. In 2023, the leadership of the Breast International Group (BIG) and National Cancer Institute (NCI)’s National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) convened a CNS Working Group to identify key challenges in the field and discuss ways that international collaborations could push forward progress in the field. This review reflects the initial discussions of the working group and addresses (1) the possible role of screening for CNS metastases, (2) optimal sequencing of local and systemic therapies among patients with HER2+ve CNS metastases, (3) management of LMD, and (4) the importance of developing innovative clinical trials for treatment and prevention of CNS metastases across breast cancer subtypes that is informed by preclinical data/basic science, with seamless knowledge translation to allow for rapid adoption into clinical care.

Screening for CNS metastases

Current ASCO and Advanced Breast Cancer (ABC)7 guidelines do not recommend routine CNS surveillance of asymptomatic patients with metastatic breast cancer25,26. However, in an era where effective local and systemic therapy options exist for patients with metastatic breast cancer and CNS metastases, the possible utility of early detection and treatment of CNS metastases should be revisited. Given a particularly high incidence of CNS metastases among patients with triple negative and HER2+ve metastatic breast cancer (at least one-third and up to half of patients will develop CNS metastases during their life-time)27, the 2022 European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines suggest that “screening at diagnosis is potentially justified in HER2+ve and triple-negative” metastatic breast cancer28. By detecting CNS metastases early, there is potential to intervene when the disease burden is low with well-tolerated and precise SRS therapy before neurologic symptoms develop. This may inform the selection/sequencing of systemic therapies, reduce the risk of death due to CNS metastases, and help preserve patients’ function, cognition, and overall quality of life.

While screening patients for CNS metastases has potential benefits, the value of this approach is yet to be solidified due to the potential for unnecessary treatments, their associated toxicities, as well as costs in resource-limited settings. In addition, a diagnosis of CNS metastases is associated with psychological morbidity, can affect patients’ lives through social stigma and exclusion, and can also result in legal issues (e.g. impact on patients’ ability to drive). Indeed, screening investigations may be associated with anxiety and a detriment to QoL29. Further, with many clinical trials still excluding patients with CNS metastases23, some physicians hesitate to uncover asymptomatic findings that limit therapeutic options and may never become clinically apparent. Finally, early detection of CNS metastases has yet to be shown to confer a survival benefit.

To assess the potential role of screening CNS imaging, Cagney et al compared the presentation, treatments, and outcomes of patients at the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center with CNS metastases from either breast cancer (not typically screened for CNS metastases) or non-small cell lung cancer (typically screened for CNS metastases) between January 2000 and December 201530. Patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer and CNS metastases had less extensive CNS metastases, with fewer patients requiring WBRT than those with metastatic breast cancer30. While the incidence of death due to CNS metastases was lower among patients with lung cancer compared to breast cancer (17.3% vs. 19.9%), the overall survival among both groups was similar 30.

The incidence of asymptomatic CNS metastases among patients with metastatic breast cancer has been evaluated in several retrospective and prospective studies31,32,33,34,35,36,37. In a retrospective cohort of 155 patients with metastatic breast cancer for whom CNS imaging was performed prior to enrollment in one of four clinical trials at two US-based cancer centers, 23 patients (15%) had occult CNS metastases and 132 (85%) did not31. All four trials involved the use of anti-angiogenic drugs. Among the patients diagnosed with CNS metastases during the study period (1998 to 2001), nearly all received WBRT and 21 (91%) died of systemic disease progression in the absence of neurologic symptoms. In this cohort, 49% had hormone receptor (HR)+ disease and 28% had HER2+ve breast cancer with a median of 3 prior lines of chemotherapy31. When compared to 73 consecutive patients (“controls”) with breast cancer treated for symptomatic CNS metastases at the Indiana University Cancer Center during a similar time-period (1996–2002), there was no difference in survival among patients with occult versus symptomatic CNS metastases31. However, it is acknowledged that available local and systemic therapies for patients with CNS metastases have substantially improved since this study was conducted.

Other literature involving more contemporary cohorts suggests that patients with asymptomatic CNS metastases who receive treatment may live longer than those who have symptomatic CNS metastases at the time of treatment. For example, in a single-center retrospective study of 683 patients with metastatic breast cancer treated for CNS metastases between 2008 and 2018, 529 (78%) patients with neurologic symptoms had a significantly shorter survival than those who were asymptomatic, even after adjustment for age, type of radiation therapy (WBRT vs SRS) and breast cancer subtype32. Data from large German and Japanese registries also suggest that patients with metastatic breast cancer (particularly those with HER2+ve disease) who have occult as opposed to symptomatic CNS metastases live longer36,37. While this data appears to support a benefit of early detection of CNS metastases, results are subject to lead-time bias.

The possible role of screening for CNS metastases among patients with breast cancer is being evaluated in several ongoing prospective trials (Table 1). However, recruitment challenges have limited the availability of data to support the practice of routine screening. Results of a single-arm trial (N = 101) that evaluated incidence of asymptomatic CNS metastases with brain imaging at enrollment and 6 months later identified a high incidence of CNS metastases among patients with metastatic breast cancer irrespective of subtype38. Patients with HR + /HER2-ve metastatic breast cancer whose disease progressed on first line endocrine-based therapy had a similar incidence of CNS metastases at 6-months (23%) as those with triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) (25%) or HER2+ve (24%) disease38. Hence, efforts to report data from relevant clinical trials that required CNS imaging prior to trial entry would also be of value, irrespective of breast cancer subtype. In addition, routine imaging of the CNS in the development of future clinical trials for patients with metastatic breast cancer should be considered to better understand the role of various systemic therapies in the prevention and/or treatment of CNS metastases. The perspectives of patients and physicians on screening for asymptomatic CNS metastases have also been evaluated39. In an international survey of 545 patients from 14 European countries with a history of breast cancer (51% HR + /HER2-ve, 30% HER2+ve and 19% TNBC), 85.3% would agree to brain imaging surveillance even in the absence of strong data to support this practice39. In a parallel survey of 529 physicians from Europe and Canada, 346 (65%) order brain imaging surveillance, but only a minority (3% “always” and 10% “sometimes”) routinely order surveillance scans 39.

Development of effective systemic options

The Graded Prognostic Index, specifically for patients with metastatic breast cancer and CNS metastases known as the Breast Graded Prognostic Assessment (GPA) index, provides a robust method to estimate prognosis40. The score is based on Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) ( ≤ 60 vs 70-80 vs 90–100), age ( ≥ 60 vs <60), number of CNS metastases ( ≥ 2 vs 1) and breast cancer subtype (basal vs luminal A vs HER2+ve or luminal B). The tool was developed based on information from 2473 patients with breast cancer and CNS metastases diagnosed between 2006 and 2017 across 18 institutions in three countries40. Even during this time period (prior to regulatory approvals of modern systemic therapy options such as tucatinib or trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd)), the median survival among patients <60 years of age with HER2+ve disease, an excellent KPS of 90–100 and a solitary CNS metastasis was 36 months. Among older patients ( ≥ 60 years of age) with multiple CNS metastases, the median survival was 24 months among those with HER2+ve disease, as long as Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) was 90–10040. These favorable outcomes of patients with HER2+ve metastatic breast cancer and CNS metastases suggest their suitability for enrollment in clinical trials; indeed, patients with CNS metastases have been well represented in some trials for HER2+ve metastatic breast cancer with successful results 41.

Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Since the publication of the GPA index, the HER2CLIMB clinical trial, which randomized patients with HER2+ve metastatic breast cancer to trastuzumab and capecitabine with or without tucatinib demonstrated impressive survival benefits associated with the use of the small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) tucatinib42. A high proportion of patients in the HER2CLIMB trial had CNS metastases (n = 291, 48%); among them, 174 (60%) had active (previously treated progressing or previously untreated) CNS metastases, and 117 (40%) had stable/previously treated CNS metastases42. About half (48.9%) of patients receiving tucatinib-based therapy with active/previously untreated CNS metastases were alive at 24 months, whereas only 21.4% of patients in the placebo arm were alive at 24 months43. Paired with longer CNS-specific progression-free survival (PFS) and greater intra-cranial objective response rate (ORR-IC), this data solidifies the intra-cranial activity of tucatinib44. Further, the risk of developing new CNS lesions as a site of first progression or death was significantly lower among patients receiving tucatinib in the HER2CLIMB trial [HR 0.55 (95% CI, 0.36–0.85)44. Such data and the fact that tucatinib reaches therapeutic levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)45 offers the tantalizing possibility that small molecule TKIs have the potential to prevent the development of CNS metastases among patients with HER2+ve breast cancer.

Antibody-drug conjugates

Historically, large antibodies and antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) were thought to be too bulky to cross the blood-brain barrier. However, as outlined by Arvanitis et al46. and Mair et al.47, the presence of CNS metastases disrupts the blood-brain barrier, making it more permeable to drugs including ADCs like T-DM148. The extra-cranial activity of the second generation HER2 ADC T-DXd is reflected intra-cranially based on the results from the TUXEDO and DEBBRAH trials, the pooled analysis of patients with CNS metastases from the DESTINY-Breast -01, -02, and -03 trials, and most recently the DESTINY-Breast12 study16,17,18,19,20. Intra-cranial response rates of up to 82.6% among patients with active, previously treated and untreated CNS metastases in the DESTINY-Breast12 trial16 have resulted in a shift in thinking among medical oncologists, given that T-DXd can be considered for medical management of CNS metastases among certain patients with HER2+ve disease28. Several multi-center retrospective experiences also corroborate this observation of high rates of durable intracranial disease control 49,50,51.

Sacituzumab govitecan (SG), is an ADC consisting of a Trop-2 monoclonal antibody linked to a payload consisting of SN38, the active metabolite of irinotecan. In the ASCENT trial of SG versus treatment of physician’s choice among patients with previously treated metastatic TNBC, 61 of 529 (12%) patients had known stable CNS metastases at baseline52. Among patients with CNS metastases, those receiving SG had numerically longer PFS but not OS compared to those receiving standard chemotherapy52. Results of a recent window-of-opportunity trial with SG demonstrate therapeutic levels of SN38 within resected brain metastasis tissue with preliminary evidence of clinical activity53. A real-world experience of 12 patients with brain metastases treated with SG reported an intracranial disease control rate of 42%; however, median intracranial PFS was only 2.7 months54. A prospective single-arm multicenter clinical trial of SG restricted to patients with active HER2-ve CNS metastases is still ongoing [NCT04647916]. Hence, at this time, data are insufficient to strongly recommend SG for the treatment of patients with active CNS metastases.

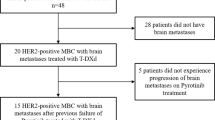

Datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd), an alternate Trop-2 directed ADC, has shown promise among patients with HER2-ve metastatic breast cancer55 and is being evaluated in two phase II trials among patients with CNS metastases [NCT06176261 (Fig. 1) and NCT05866432]. The inclusion of a cohort of patients with LMD is an important feature of DATO-BASE while TUXEDO-2 allows for the inclusion of patients with active CNS metastases and coexisting type II LMD. Preliminary results from the first stage of TUXEDO-2 reported an intracranial response rate of 37.5% in patients with metastatic TNBC and active CNS metastases56. The HER3-targeting ADC patritumab deruxtecan is also being evaluated in the context of CNS metastases in patients with breast and non-small cell lung cancer; a cohort of patients with LMD is included [NCT05865990]. Importantly, the inclusion of patient cohorts with LMD, as well as patients with CNS metastases from other solid tumors, should be considered when appropriate and can serve as a paradigm for future studies.

Options for patients with HR + /HER2-ve brain metastases

While limited data regarding CNS efficacy of CDK4/6 inhibitors is available from pivotal randomized trials for patients with HR + /HER2-ve metastatic breast cancer57, abemaciclib is known to penetrate the brain and has demonstrated some CNS activity as a single agent (intracranial clinical benefit rate (iCBR) of 24%) in the JPBO phase II trial58. Elacestrant, an oral SERD indicated for ESR1 mutant, metastatic breast cancer, has excellent CNS penetration and is being evaluated in combination with abemaciclib for patients with ER+ breast cancer and brain metastases [NCT04791384 and NCT05386108]. Imlunestrant plus abemaciclib has already demonstrated efficacy in the EMBER-3 trial59, however, CNS-specific efficacy of this combination has not yet been established. Several other agents are also in development for patients with HR + /HER2-ve disease and CNS metastases (Table 2).

Immunotherapy

The clinical impact of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in patients with CNS metastases from breast cancer remains unclear at this time. In a study of 57 patients with diverse tumor histologies, nine (16%) of whom had untreated CNS metastases and 48 (84%) had recurrent or progressive CNS metastases, the intracranial benefit rate was 42.1%60. For the small subset of patients with previously untreated CNS metastases (four patients with breast cancer were represented), the median intracranial PFS was 1.6 months60. In a single-arm, phase II study in which atezolizumab was added to HER2-directed therapy, intracranial outcomes did not exceed that expected from historical controls61. Given the small and heterogenous populations, which did not require expression of predictive biomarkers of response to immunotherapy, further evaluation of immunotherapy in biomarker enriched subsets of patients may still be of interest61. The fact that the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) biomarker is expressed in a high proportion of patients with breast cancer and CNS metastases (particularly among those with triple negative disease) supports consideration for evaluation of ICIs either alone or in combination with other agents, such as those targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3), T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3), or T cell immunoreceptor with immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT) in this setting 62,63.

Novel therapeutics

A deeper understanding of the basic biology of CNS metastases among patients with metastatic breast cancer may help inform the next generation of systemic therapies for the treatment and prevention of disease in the brain. Through profiling efforts, the genetic heterogeneity of metastatic breast cancer and branched evolution is better understood64. The fact that ~22-36% of CNS metastases have a discordance in ER, PR or HER2 expression compared to the matched primary tumor65,66, emphasizes the relevance of clinically actionable biomarkers in the brain and the need for non-invasive methods (e.g., liquid biopsy, molecular imaging techniques) to characterize CNS metastases. A better understanding of the blood-tumor barrier67,68, clinical, pathology and molecular factors that “drive” breast cancer to metastasize to the brain as well as the microenvironment of these lesions in the CNS, is also imperative.

Patient-specific factors such as germline pathogenic alterations in the BRCA gene should also be considered. In the EMBRACA trial, patients with a HER2-ve metastatic breast cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation, the poly (ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor talazoparib improved PFS (although not OS) compared to standard-of-care chemotherapy69,70; patients with previously treated, stable CNS metastases had similar benefit from talazoparib as those without CNS metastases. In the BROCADE3 trial, addition of the PARP inhibitor veliparib to chemotherapy (carboplatin plus paclitaxel) improved PFS but not OS in the overall patient population71,72. However, the hazard ratios for PFS and OS among ~5% of patients enrolled in BROCADE3 with previously treated/stable CNS metastases were 2.08 (95% CI 0.78–5.52) and 1.682 (95%CI 0.674–4.201)71,72. The ongoing phase IIIb LUCY trial will shed more light on activity of olaparib among patients with metastatic HER2-ve breast cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation who have previously treated, stable CNS metastases 73.

Choice/integration of local and systemic therapy

Historically, the mainstay of treatment of HER2+ve CNS metastases was local therapy with surgery and/or radiation. However, several systemic therapy options now exist, as outlined in recent NCCN Guidelines Version 1.202241. These include small molecules TKIs in combination with chemotherapy (e.g., HER2CLIMB (tucatinib + trastuzumab + capecitabine) regimen, lapatinib plus capecitabine, and neratinib plus capecitabine), ADCs (T-DM1 and T-DXd), as well as pertuzumab in combination with high dose trastuzumab41. HER2 non-specific options listed in the NCCN guidelines include capecitabine74, cisplatin, etoposide, cisplatin in combination with etoposide, and high dose methotrexate41. Capecitabine, for example, has demonstrated a CNS-ORR of 38% among patients with HR + /HER2-ve breast cancer (n = 42) and 61% among those with TNBC (n = 18) in a retrospective cohort of patients with measurable CNS disease74. Notably, given limited data to-date, prospective studies to better define intra-cranial activity of standard cytotoxic agents would be of value.

Given the availability of both local and systemic options for treating HER2+ve CNS metastases, clinicians and patients often face challenging decisions regarding how to sequence these treatments. Factors generally favoring a local treatment approach include: i) symptomatic lesions and/or those with imminent neurologic complications, ii) controlled extra-cranial disease (allowing patients to continue the same systemic therapy longer), and iii) isolated CNS metastases (preserving systemic approaches until other areas of disease develop) (Fig. 2). In cases when surgery is not required and the CNS disease is amenable to SRS, local radiotherapy should be considered with discussion at a multidisciplinary case conference to weigh the relative expected benefit of systemic therapy versus SRS. Patients’ preferences should be considered as well.

ASCO guidelines currently recommend that patients with HER2+ve metastatic breast cancer with CNS progression in the setting of stable extra-cranial disease should be treated with local therapy to the brain while maintaining their current line of systemic treatment26,75. However, considering new data demonstrating CNS activity of several anti-HER2 targeted agents it is possible that a switch or escalation of systemic therapy may improve patients’ outcomes. To investigate this possibility, the BRIDGET/BRE21-516 single-arm, phase II clinical trial of tucatinib added to trastuzumab/pertuzumab or T-DM1 among patients with isolated intracranial progression of HER2+ve breast cancer is being conducted [NCT05323955]. A similar “InTTercePT” study is evaluating the addition of tucatinib to trastuzumab/pertuzumab in patients with HER2+ve metastatic breast cancer after local therapy for isolated brain progression [NCT05041842]. These are important trials, particularly given that the scenario of isolated CNS progression among patients with HER2+ve metastatic disease is not infrequent 76,77.

Whether radiation therapy should be used upfront or deferred in favor of a systemic approach may also depend on the risk of radiation necrosis (RN), resulting from damage of parenchymal brain tissue following radiation to the brain78. RN is an unwanted complication of brain radiotherapy because it can be symptomatic and difficult to distinguish from tumor progression79. Commonly used ADCs are associated with a higher risk of RN if used concurrently with SRS (defined as treatment ≤7 days before or ≤21 days after an ADC)78. Compared to a sequential approach, the risk of grade 4 to 5 symptomatic RN was 7.1% versus 0.7% in a single center, retrospective cohort report of 98 patients who were treated with SRS for brain metastases and received least 1 dose of T-DXd, T-DM1 or SG80. For patients who received re-irradiation for CNS metastases, the risk of symptomatic RN at 24 months among patients who received concurrent versus sequential therapy with an ADC was 42.0% versus 9.4%80. While a lower incidence of RN has been reported by others81, this suggests that timing of brain radiotherapy should be carefully considered among patients receiving an ADC, avoiding concurrent therapy when possible, to mitigate risk of RN. The European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO) has published guidelines to address the integration of novel systemic therapies more broadly with radiotherapy82, however, it is acknowledged that data to support recommendations regarding safety of concurrent treatment approaches is generally sparse.

Leptomeningeal disease

LMD is a less common form of CNS metastases, which historically has been associated with a particularly poor prognosis. The median survival after a diagnosis of LMD is only 5.1 months among patients with HR + /HER2-ve breast cancer, 5.6 months among those with HER2+ve and 3.0 months among those with TNBC83,84. Given the location of disease in the CNS, several studies have evaluated the use of intrathecal therapies for patients with LMD in hopes of increasing drug delivery to the leptomeninges.

For patients with HER2+ve LMD, intrathecal trastuzumab has been evaluated in three prospective, single arm trials with sample sizes ranging from 16 to 26 patients84. The median survival among patients in these studies ranged from 7.3 months to 10.5 months, suggesting some clinically meaningful benefit compared to historical controls. However, uptake of intrathecal trastuzumab and other intrathecal therapies in the “real world” has been low, possibly due to a lack of a high-quality data suggesting a survival advantage of this approach, as well as important toxicities and detriment to QoL associated with the invasive nature of intrathecal therapies that often require placement of an Ommaya Reservoir85. Poor performance status of patients with LMD also limits the use of more invasive treatments.

The ESME database highlighted that while patients with metastatic HER2+ve and TNBC are most likely to develop CNS metastases, the majority of the 312 patients receiving intrathecal therapies (53.8%) had HR + /HER2-ve breast cancer83. Further, the group of patients identified to have LMD based on receipt of intrathecal therapies was enriched for lobular histology compared to controls (23.4% versus 12.7%, < 0.001)83. Bartsch et al. have recently reviewed the use of standard systemic and intrathecal therapies among patients across various breast cancer subtypes with LMD, highlighting the lack of randomized clinical trials in this high-need patient population84. The only randomized trial of systemic therapy plus/minus intrathecal therapy to-date has shown a PFS advantage associated with the use of intrathecal liposomal cytarabine but no OS benefit 86.

In addition to prospective studies, intriguing retrospective data has been reported for patients with this relatively rare site of disease. For example, in a case series of eight heavily pre-treated patients with HER2+ve LMD treated with T-DXd, the clinical benefit rate was 100% and four patients (50%) had an objective partial response to treatment87. In a subgroup of 19 patients with HER2+ve LMD treated with T-DXd in the “real world” ROSET-BM study, an impressive 87.1% of patients were alive at 12 months50. The use of the HER2CLIMB regimen is also actively being evaluated among patients with HER2+ve LMD [NCT06016387, NCT03501979, NCT05800275]. The TBCRC 049 clinical trial demonstrated that tucatinib reaches therapeutic levels in the CSF and that the HER2CLIMB regimen is associated with improvements in symptoms and QoL. Median overall survival was 10 months, exceeding historical control estimates88. While rationale exists for poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors to be effective in the CNS of patients with a germline BRCA mutation, evidence supporting their use in LMD is at the case report level at this time89. Finally, immune checkpoint blockade with single agent pembrolizumab90 and the combination of pembrolizumab plus ipilumumab91 have demonstrated signals of efficacy among heavily pre-treated patients with LMD across histologies. As technologies improve, evaluation of CSF for predictive biomarkers of response and resistance may be promising, particularly given successful genomic and transcriptomic analyses of CSF in the two aforementioned immunotherapy studies 92.

Finally, from a local perspective, the use of proton craniospinal irradiation (pCSTI) may provide benefit compared to standard-of-care photon-involved field radiotherapy (IFRT). In a phase II clinical trial, 63 patients with metastatic breast cancer or non-small-cell lung cancer and LMD were randomized to either pCSTI or photon IFRT93. An improvement in CNS PFS (median 7.5 months vs 2.3 months, p < 0.001) and OS (median 9.9 months vs 6.0 months, p = 0.029) is encouraging93. Future evaluation of pCSTI in combination/sequence with relevant systemic therapies is of interest. In addition to optimizing therapies for LMD, it is important to understand the full extent of LMD not only in the brain but also in the spine to inform the extent of local therapy and adequate response assessment 26,94.

Eligibility of patients with CNS metastases in clinical trials

As patients with metastatic breast cancer live longer, the incidence of CNS metastases has increased. Nonetheless, patients with CNS metastases have often been excluded from clinical trials23. Broadening eligibility criteria for patients with CNS metastases in clinical trials is crucial to understand the CNS efficacy of new agents, to ensure generalizability of results in real-world patient populations, as well as to improve feasibility of recruitment and successful study completion. Hence, per the ASCO Friends of Cancer Research Brain Metastases Research Group, patients with treated and/or clinically stable CNS metastases should be regularly enrolled in trials, with exclusion only when there is a compelling rationale21. Indeed, despite the possibility of reduced life expectancy in certain patients with CNS metastases and concerns regarding increased risk of neurological toxicity, current literature does not suggest higher rates of serious adverse events in these patients95. Similarly, patients with active (namely progressing or untreated) CNS metastases should not be automatically excluded from clinical trials, and many methods are available (e.g., CNS-specific cohorts) to generate data in early phase clinical trials to inform the inclusion (or not) of patients with active brain metastases in later phase studies. For patients with LMD, dedicated studies or specific cohorts within larger studies are strongly needed. Finally, even when trials are available, it can be difficult for patients and their providers to efficiently search for and identify trials outside their local centers; this represents another unmet need to be urgently addressed.

CNS prevention

With the established efficacy of HER2-targeted systemic therapies in the CNS, trials investigating the possible preventative role of these agents are ongoing (e.g., the addition of maintenance tucatinib to trastuzumab and pertuzumab in the first line setting for patients with HER2+ve metastatic breast cancer [HER2CLIMB05; NCT05132582]). In the adjuvant setting, the KATHERINE trial of T-DM1 versus trastuzumab for patients with residual disease following neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for HER2+ve breast cancer did not show a reduction in the incidence of CNS metastases as a first site of recurrence96. However, there is hope that the addition of tucatinib to T-DM1 in the postneoadjuvant CompassHER2 Residual Disease (RD) trial (A011801; NCT04457596), may be more effective in this regard. Similarly, in patients with early-stage triple negative disease, the addition of pembrolizumab to standard-of-care neo-adjuvant chemotherapy did not reduce the risk of future development of CNS metastases in the KEYNOTE-522 trial97. In fact, more than half of distant events observed were CNS metastases, and similar findings have been reported in relevant I-SPY trials98. For patients with HER2-ve metastatic breast cancer and germline BRCA1/2 mutations, it is intriguing that the incidence of CNS metastases among patients in the olaparib arm of the OlympiA trial has a numerically lower incidence of CNS metastases than the placebo arm (2.6% vs. 4.2%) 99.

Given CNS activity of ADCs like T-DXd, other ADCs with different antibody targets and different payloads hold promise as effective therapies for patients with breast cancer and CNS metastases. Hence, with numerous ADCs in development, medical management of CNS metastases has the potential to expand significantly for patients with HER2-low and HER2-ve disease. However, while ADCs have shown efficacy among patients with CNS metastases in both pre-clinical models and clinical trials4,16,17,18,19,20,49,100,101, their ability to penetrate an intact blood brain barrier has not yet been demonstrated. This raises questions about the potential for ADCs to prevent the development of CNS metastases. Nevertheless, it is possible that effective ADCs like T-DXd may delay the development of CNS metastases due to excellent control of extra-cranial disease and thereby change the natural history of HER2+ve metastatic breast cancer. The combination of T-DM1 and low-dose temozolomide has also been explored in a small cohort of 12 patients with HER2+ve CNS metastases, among whom two patients developed new brain lesions after a median follow-up duration of 9.6 months102; evaluation of existing and novel agents for the secondary prevention of CNS metastases would be of interest.

In light of a low incidence of CNS metastases as a first site of metastatic recurrence, which appears to be similar irrespective of pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant therapy96,97,98, biomarkers to enrich populations of patients at particularly high risk of CNS metastases would be of value. In addition, further investigation of the biological “drivers” of CNS metastases is required to inform the next generation of therapeutics with potential to eradicate micrometastatic lesions in the CNS and to ultimately prevent the development of CNS metastases 103,104,105,106,107,108.

Future directions

The management of patients with metastatic breast cancer and CNS metastases is rapidly changing, particularly for those with HER2+ve disease. With respect to biomarkers, it is important to consider the HR and HER2 status of disease in the CNS given that a change of breast cancer subtype between primary tumor and CNS metastases can occur63,64. More recently, differences in HER2-low status of the primary tumor and CNS metastases have also been observed109,110. Brain metastases also harbor other potentially clinically significant alterations not detected in the original primary breast cancer59, which can now be interrogated via innovative molecular technologies (e.g. spatial transcriptomics, single-cell profiling). Given potential morbidity associated with neuro-surgical intervention, non-invasive methods of tumor subtyping via liquid biopsy (e.g. blood-based and/or CSF-derived circulating tumor DNA), MRI radiomics, and functional imaging biomarkers are also under investigation111,112. Such molecular and imaging technologies offer promising avenues for risk stratification, early detection, non-invasive disease monitoring, and therapeutic targeting in the field of brain metastases research.

Finally, it is important to address the type of studies required to move the field of CNS metastases forward. While randomized trials should ideally be performed to answer critical questions that impact clinical practice, this may not be feasible for “rare” diseases such as LMD and specific subtypes of CNS metastases (e.g., isolated CNS recurrence after neo/adjuvant therapy for early stage disease). To address this, other methods of data generation must be considered. For example, in the case of LMD, a multicenter registry has been launched in the U.S. (Fig. 3) with similar efforts underway in Europe, and small single-arm studies are in progress. If promising signals arise from these studies, larger randomized trials may be pursued with international collaborations. Based on recommendations from The International Rare Diseases Research Consortium (IRDRC), Federal Drugs Agency (FDA), and European Medicines Association (EMA), crossover and adaptive trial designs are encouraged and Bayesian methods (e.g. incorporation of historical data with trial data) can also be considered 113.

Conclusions

The field of breast cancer and CNS metastases is rapidly changing. Given the activity of HER2-directed systemic therapies in the brain, the therapy paradigm for patients with HER2+ve CNS metastases has shifted, and multidisciplinary discussions to weigh the relative merits of local therapy and systemic therapy have become increasingly critical, as has the input of patients themselves. Advances to the care of patients with HER2-ve and HER2-low CNS metastases may also emerge, given that numerous novel ADCs are in development, as well as small molecule agents specifically designed for improved BBB penetration. As patients live longer and receive multiple courses of radiation, the relevance of developing accurate, noninvasive tests to distinguish radiation necrosis from disease progression increases. And despite the progress made in treatment options for patients with CNS metastases, options for patients with LMD remain limited and suboptimal. Concerted collaboration will be required to make real progress in this uncommon manifestation of breast cancer. Further, data to guide sequencing of treatment modalities and specific drug regimens is still required. Finally, facilitating worldwide access of patients and providers to high quality, up-to-date educational and supportive resources focused on the problem of CNS disease in breast cancer remains an unmet challenge. International collaborations through the BIG–NCTN as well as the ABC Global Alliance https://www.abcglobalalliance.org/, including strong input from patient advocates, are underway to tackle these and other unanswered questions [Figs. 4, 5].

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Chang, E. L. et al. Neurocognition in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery or radiosurgery plus whole-brain irradiation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 10, 1037–1044 (2009).

Sahgal, A. et al. Phase 3 trials of stereotactic radiosurgery with or without whole-brain radiation therapy for 1 to 4 brain metastases: individual patient data meta-analysis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 91, 710–717 (2015).

Sahgal, A. et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery alone for brain metastases. Lancet Oncol. 16, 249–250 (2015).

Brown, P. D. et al. Effect of radiosurgery alone vs radiosurgery with whole brain radiation therapy on cognitive function in patients with 1 to 3 brain metastases: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 316, 401–409 (2016).

Lamba, N. et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery versus whole-brain radiotherapy after intracranial metastasis resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiat. Oncol. 12, 106 (2017).

Akanda, Z. Z. et al. Post-operative stereotactic radiosurgery following excision of brain metastases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother. Oncol. 142, 27–35 (2020).

Palmer, J. D. et al. Multidisciplinary patient-centered management of brain metastases and future directions. Neurooncol. Adv. 2, vdaa034 (2020).

Brown, P. D. et al. Postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery compared with whole brain radiotherapy for resected metastatic brain disease (NCCTG N107C/CEC·3): a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 18, 1049–1060 (2017).

Mahajan, A. et al. Post-operative stereotactic radiosurgery versus observation for completely resected brain metastases: a single-centre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 18, 1040–1048 (2017).

Patel, K. R. et al. Comparing preoperative with postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery for resectable brain metastases: a multi-institutional analysis. Neurosurgery 79, 279–285 (2016).

Huff, W. X. et al. Efficacy of pre-operative stereotactic radiosurgery followed by surgical resection and correlative radiobiological analysis for patients with 1–4 brain metastases: study protocol for a phase II trial. Radiat. Oncol. 13, 252 (2018).

Prabhu, R. S. et al. Preoperative stereotactic radiosurgery before planned resection of brain metastases: updated analysis of efficacy and toxicity of a novel treatment paradigm. J. Neurosurg. 131, 1387–1394 (2018).

Prabhu, R. S. et al. Preoperative vs postoperative radiosurgery for resected brain metastases: a review. Neurosurgery 84, 19–29 (2019).

Scampoli, C. et al. Memantine in the prevention of radiation-induced brain damage: a narrative review. Cancers (Basel) 14, 2736 (2022).

Lin, N. U. et al. Tucatinib vs placebo, both in combination with trastuzumab and capecitabine, for previously treated ERBB2 (HER2)-positive metastatic breast cancer in patients with brain metastases: Updated exploratory analysis of the HER2CLIMB randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 9, 197–205 (2023).

Harbeck, N. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in HER2-positive advanced breast cancer with or without brain metastases: a phase 3b/4 trial. Nat Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03261-7 (2024).

Bartsch, R. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in HER2-positive breast cancer with brain metastases: a single-arm, phase 2 trial. Nat. Med. 28, 1840–1847 (2022).

Pérez-García, J. M. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with central nervous system involvement from HER2-positive breast cancer: the DEBBRAH trial. Neuro Oncol. 25, 157–166 (2023).

Hurvitz, S. A. et al. 377O A pooled analysis of trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) in patients (pts) with HER2-positive (HER2+) metastatic breast cancer (mBC) with brain metastases (BMs) from DESTINY-Breast (DB) -01, -02, and -03. Ann. Oncol. 34, S334–S390 (2023).

Bartsch, R. et al. Results of a patient-level pooled analysis of three studies of trastuzumab deruxtecan in HER2-positive breast cancer with active brain metastasis. ESMO Open 10, 104092 (2025).

Lin, N. U. et al. Modernizing clinical trial eligibility criteria: recommendations of the American Society of Clinical Oncology-Friends of Cancer Research Brain Metastases Working Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 3760–3773 (2017).

Mehta, G. U. et al. US Food and Drug Administration regulatory updates in neuro-oncology. J. Neurooncol. 153, 375–381 (2021).

Corbett, K. et al. Central nervous system–specific outcomes of phase 3 randomized clinical trials in patients with advanced breast cancer, lung cancer, and melanoma. JAMA Oncol. 7, 1062–1064 (2021).

Sharma, A. E. et al. Assessment of phase 3 randomized clinical trials including patients with leptomeningeal disease: a systematic review. JAMA Oncol. 9, 566–567 (2023).

Ramakrishna, N. et al. Management of advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive breast cancer and brain metastases: ASCO guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 2636–2655 (2022).

Cardoso, F. et al. 6th and 7th International consensus guidelines for the management of advanced breast cancer (ABC guidelines 6 and 7). Breast 76, 103756 (2024).

Kuksis, M. et al. The incidence of brain metastases among patients with metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuro Oncol. 23, 894–904 (2021).

Gennari, A. et al. ESMO Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 32, 1475–1495 (2021).

Nguyen, L. B. et al. Impact of interventions on the quality of life of cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal research. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 21, 112 (2023).

Cagney, D. N. et al. Implications of screening for brain metastases in patients with breast cancer and non–small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 4, 1001–1003 (2018).

Miller, K. D. et al. Occult central nervous system involvement in patients with metastatic breast cancer: prevalence, predictive factors and impact on overall survival. Ann. Oncol. 14, 1072–1077 (2003).

Gao, Y. K. et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes of women with symptomatic and asymptomatic breast cancer brain metastases: A single-center retrospective study. Oncologist 26, e1951–e1961 (2021).

Koiso, T. et al. A case-matched study of stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with brain metastases: comparing treatment results for those with versus without neurological symptoms. J. Neurooncol. 130, 581–590 (2016).

Morikawa, A. et al. Characteristics and prognostic factors for patients with HER2-overexpressing breast cancer and brain metastases in the era of HER2-targeted therapy: an argument for earlier detection. Clin. Breast Cancer 18, 353–361 (2018).

Maurer, C. et al. Risk factors for the development of brain metastases in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. ESMO Open 3, e000440 (2018).

Laakmann, E. et al. Characteristics and clinical outcome of breast cancer patients with asymptomatic brain metastases. Cancers 12, 2787 (2020).

Niikura, N. et al. Treatment outcomes and prognostic factors for patients with brain metastases from breast cancer of each subtype: A multicenter retrospective analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 147, 103–112 (2014).

Ahmed, K. A. et al. Phase II trial of brain MRI surveillance in stage IV breast cancer. Neuro Oncol. noaf018 (2025).

Annals of Oncology (2024) 35: S357-S405. https://doi.org/10.1016/annonc/annonc1579

Sperduto, P. W. et al. Survival in patients with brain metastases: Summary report on the updated diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment and definition of the eligibility quotient. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 3773–3784 (2020).

Horbinski, C. et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: central nervous system cancers, version 2.2022. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 21, 12–20 (2023).

Murthy, R. K. et al. Tucatinib, trastuzumab, and capecitabine for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 597–609 (2020).

Curigliano, G. et al. Tucatinib versus placebo added to trastuzumab and capecitabine for patients with pretreated HER2+ metastatic breast cancer with and without brain metastases (HER2CLIMB): final overall survival analysis. Ann. Oncol. 33, 321–329 (2022).

Lin, N. U. et al. Intracranial efficacy and survival with tucatinib plus trastuzumab and capecitabine for previously treated HER2-positive breast cancer with brain metastases in the HER2CLIMB trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 2610–2619 (2020).

Stringer-Reasor, E. M. et al. Pharmacokinetic (PK) analyses in CSF and plasma from TBCRC049, an ongoing trial to assess the safety and efficacy of the combination of tucatinib, trastuzumab and capecitabine for the treatment of leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) in HER2 positive breast cancer. JCO 39, 1044–1044 (2021).

Arvanitis, C. D., Ferraro, G. B. & Jain, R. K. The blood-brain barrier and blood-tumour barrier in brain tumours and metastases. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 26–41 (2020).

Mair, M. J. et al. Understanding the activity of antibody-drug conjugates in primary and secondary brain tumours. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20, 372–389 (2023).

Montemurro, F. et al. Trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer and brain metastases: exploratory final analysis of cohort 1 from KAMILLA, a single-arm phase IIIb clinical trial☆. Ann. Oncol. 31, 1350–1358 (2020).

Kabraji, S. et al. Preclinical and clinical efficacy of trastuzumab deruxtecan in breast cancer brain metastases. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 174–182 (2023).

Niikura, N. et al. Treatment with trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer and brain metastases and/or leptomeningeal disease (ROSET-BM). NPJ Breast Cancer 9, 82 (2023).

Pearson, J. et al. A comparison of the efficacy of trastuzumab deruxtecan in advanced HER2-positive breast cancer: active brain metastasis versus progressive extracranial disease alone. ESMO Open 8, 102033 (2023).

Bardia, A. et al. Sacituzumab govitecan in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1529–1541 (2021).

Balinda, H. U. et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan in patients with breast cancer brain metastases and recurrent glioblastoma: a phase 0 window-of-opportunity trial. Nat. Commun. 15, 6707 (2024).

Dannehl, D. et al. The efficacy of sacituzumab govitecan and trastuzumab deruxtecan on stable and active brain metastases in metastatic breast cancer patients-a multicenter real-world analysis. ESMO Open 9, 102995 (2024).

Pistilli, B. et al. VP1-2025: Datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd) vs chemotherapy (CT) in previously-treated inoperable or metastatic hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative (HR+/HER2–) breast cancer (BC): Final overall survival (OS) from the phase III TROPION-Breast01 trial. Ann. Oncol. 36, 348–350 (2025).

Annals of Oncology (2024) 9: 1-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/esmoop/esmoop103200.

Nguyen, L. V. et al. Central nervous system-specific efficacy of CDK4/6 inhibitors in randomized controlled trials for metastatic breast cancer. Oncotarget 10, 6317–6322 (2019).

Tolaney, S. M. et al. A phase II study of abemaciclib in patients with brain metastases secondary to hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res 26, 5310–5319 (2020).

Jhaveri, K. L. et al. Imlunestrant with or without Abemaciclib in Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 392, 1189–1202 (2025).

Brastianos, P. K. et al. Pembrolizumab in brain metastases of diverse histologies: phase 2 trial results. Nat. Med 29, 1728–1737 (2023).

Giordano, A. et al. A phase II study of atezolizumab, pertuzumab, and high-dose trastuzumab for central nervous system metastases in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 30, 4856–4865 (2024).

Joller, N. et al. LAG-3, TIM-3, and TIGIT: Distinct functions in immune regulation. Immunity 57, 206–222 (2024).

Chehade, R. et al. PD-L1 expression in breast cancer brain metastases. Neurooncol. Adv. 4, vdac154 (2022).

Brastianos, P. K. et al. Genomic characterization of brain metastases reveals branched evolution and potential therapeutic targets. Cancer Discov. 5, 1164–1177 (2015).

Hulsbergen, A. F. C. et al. Subtype switching in breast cancer brain metastases: a multicenter analysis. Neuro Oncol. 22, 1173–1181 (2020).

Thulin, A. et al. Discordance of PIK3CA and TP53 mutations between breast cancer brain metastases and matched primary tumors. Sci. Rep. 11, 23548 (2021).

Lockman, P. R. et al. Heterogeneous blood-tumor barrier permeability determines drug efficacy in experimental brain metastases of breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 5664–5678 (2010).

Gril, B. et al. HER2 antibody-drug conjugate controls growth of breast cancer brain metastases in hematogenous xenograft models, with heterogeneous blood-tumor barrier penetration unlinked to a passive marker. Neuro Oncol. 22, 1625–1636 (2020).

Litton, J. K. et al. Talazoparib in patients with advanced breast cancer and a germline BRCA mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 753–763 (2018).

Litton, J. K. et al. Talazoparib versus chemotherapy in patients with germline BRCA1/2-mutated HER2-negative advanced breast cancer: final overall survival results from the EMBRACA trial. Ann. Oncol. 31, 1526–1535 (2020).

Diéras, V. et al. Veliparib with carboplatin and paclitaxel in BRCA-mutated advanced breast cancer (BROCADE3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 21, 1269–1282 (2020).

Diéras, V. et al. Veliparib with carboplatin and paclitaxel in BRCA-mutated advanced breast cancer (BROCADE3): Final overall survival results from a randomized phase 3 trial. Eur. J. Cancer 200, 113580 (2024).

Gelmon, K. A., Walker, G. P., Fisher, G. V. & McCutcheon, S. C. LUCY: A phase IIIb, real-world study of olaparib in HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer patients with a BRCA mutation. Ann. Oncol. 29, viii120 (2018).

Gouveia, M. C. et al. Activity of capecitabine for central nervous system metastases from breast cancer. Ecancermedicalscience 17, 1638 (2023).

Ramakrishna, N. et al. Recommendations on disease management for patients with advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer and brain metastases: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 2804–2807 (2018).

Kojundzic, I. et al. Brain metastases in the setting of stable versus progressing extracranial disease among patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 24, 156–161 (2024).

Li, A. Y. et al. Association of brain metastases with survival in patients with limited or stable extracranial disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e230475 (2023).

Vellayappan, B. et al. A systematic review informing the management of symptomatic brain radiation necrosis after stereotactic radiosurgery and international stereotactic radiosurgery society recommendations. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 118, 14–28 (2024).

Chao, S. T. et al. Challenges with the diagnosis and treatment of cerebral radiation necrosis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 87, 449–457 (2013).

Lebow, E. S. et al. Symptomatic necrosis with antibody-drug conjugates and concurrent stereotactic radiotherapy for brain metastases. JAMA Oncol. 9, 1729–1733 (2023).

Khatri, V. M. et al. Multi-institutional report of trastuzumab deruxtecan and stereotactic radiosurgery for HER2 positive and HER2-low breast cancer brain metastases. NPJ Breast Cancer 10, 100 (2024).

Meattini, I. et al. International multidisciplinary consensus on the integration of radiotherapy with new systemic treatments for breast cancer: European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO)-endorsed recommendations. Lancet Oncol. 25, e73–e83 (2024).

Carausu, M. et al. Breast cancer patients treated with intrathecal therapy for leptomeningeal metastases in a large real-life database. ESMO Open 6, 100150 (2021).

Bartsch, R. et al. Pharmacotherapy for leptomeningeal disease in breast cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 122, 102653 (2024).

Franzoi, M. A. et al. Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis in patients with breast cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 135, 85–94 (2019).

Le Rhun, E. et al. Intrathecal liposomal cytarabine plus systemic therapy versus systemic chemotherapy alone for newly diagnosed leptomeningeal metastasis from breast cancer. Neuro Oncol. 22, 524–538 (2020).

Alder, L. et al. Durable responses in patients with HER2+ breast cancer and leptomeningeal metastases treated with trastuzumab deruxtecan. NPJ Breast Cancer 9, 19 (2023).

O’Brien, B. J. et al. Tucatinib-trastuzumab-capecitabine for treatment of leptomeningeal metastasis in HER2+ breast cancer: TBCRC049 phase 2 study results. JCO. 42, (2024).

Exman, P. et al. Response to olaparib in a patient with germline BRCA2 mutation and breast cancer leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. NPJ Breast Cancer 5, 46 (2019).

Brastianos, P. K. et al. Single-arm, open-label phase 2 trial of pembrolizumab in patients with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Nat. Med. 26, 1280–1284 (2020).

Brastianos, P. K. et al. Phase II study of ipilimumab and nivolumab in leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Nat. Commun. 12, 5954 (2021).

Prakadan, S. M. et al. Genomic and transcriptomic correlates of immunotherapy response within the tumor microenvironment of leptomeningeal metastases. Nat. Commun. 12, 5955 (2021).

Yang, J. T. et al. Randomized phase II trial of proton craniospinal irradiation versus photon involved-field radiotherapy for patients with solid tumor leptomeningeal metastasis. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 3858–3867 (2022).

Le Rhun, E. et al. EANO-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with leptomeningeal metastasis from solid tumours. Ann. Oncol. 28, iv84–iv99 (2017).

Tsimberidou, A. M. et al. Phase I clinical trial outcomes in 93 patients with brain metastases: the MD anderson cancer center experience. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 4110–4118 (2011).

Loibl, S. et al. Phase III study of adjuvant ado-trastuzumab emtansine vs trastuzumab for residual invasive HER2-positive early breast cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and HER2-targeted therapy: KATHERINE final IDFS and updated OS analysis. AACR. 84, Abstract GS03-12 (2024).

Pusztai, L. et al. Event-free survival by residual cancer burden with pembrolizumab in early-stage TNBC: exploratory analysis from KEYNOTE-522. Ann. Oncol. 35, 429–436 (2024).

Clark, A. S. et al. Neoadjuvant T-DM1/pertuzumab and paclitaxel/trastuzumab/pertuzumab for HER2+ breast cancer in the adaptively randomized I-SPY2 trial. Nat. Commun. 12, 6428 (2021).

Geyer, C. E. Jr et al. Overall survival in the OlympiA phase III trial of adjuvant olaparib in patients with germline pathogenic variants in BRCA1/2 and high-risk, early breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 33, 1250–1268 (2022).

Askoxylakis, V. et al. Preclinical efficacy of ado-trastuzumab emtansine in the brain microenvironment. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 108, djv313 (2015).

Ghamasaee, P., Balinda, H., Brenner, A., Floyd, J. A phase 0 clinical trial of sacituzumab govitecan in patients with breast cancer brain metastases and recurrent glioblastoma. AACR. 83, Abstract P1-14-04 (2023).

Jenkins, S. et al. Phase I study and cell-free DNA analysis of T-DM1 and metronomic temozolomide for secondary prevention of HER2-positive breast cancer brain metastases. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 1450–1459 (2023).

Kim, A. E. et al. Leveraging translational insights toward precision medicine approaches for brain metastases. Nat. Cancer 4, 955–967 (2023).

Zeng, Q. et al. Synaptic proximity enables NMDAR signalling to promote brain metastasis. Nature 573, 526–531 (2019).

Bos, P. D. et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to the brain. Nature 459, 1005–1009 (2009).

Berghoff, A. S. et al. Predictive molecular markers in metastases to the central nervous system: recent advances and future avenues. Acta Neuropathol. 128, 879–891 (2014).

Van Swearingen, A. E. D. et al. Genomic and immune profiling of breast cancer brain metastases. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 13, 99 (2025).

Morgan, A. J., Giannoudis, A. & Palmieri, C. The genomic landscape of breast cancer brain metastases: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 22, e7–e17 (2021).

Chehade, R. et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-low breast cancer brain metastases: an opportunity for targeted systemic therapies in a high-need patient population. JCO Precis Oncol. 8, e2300487 (2024).

Moss, N. S. et al. Incidence of HER2-expressing brain metastases in patients with HER2-null breast cancer: a matched case analysis. NPJ Breast Cancer 9, 86 (2023).

Doebley, A. L. et al. A framework for clinical cancer subtyping from nucleosome profiling of cell-free DNA. Nat. Commun. 13, 7475 (2022).

Nowakowski, A. et al. Radiomics as an emerging tool in the management of brain metastases. Neurooncol. Adv. 4, vdac141 (2022).

Day, S. et al. Recommendations for the design of small population clinical trials. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 13, 195 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the BIG and NCTN Coordinating Group, including David Cameron, Eric Winer, and Larry Norton. We are grateful to the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF) for supporting the BIG-NCTN collaboration, including the BIG-NCTN Annual Meetings. We would also like to thank the BIG and NCTN patient advocates and all the participants of the 2024 BIG-NCTN Annual Meeting for their valuable input including: Ayal Aizer, Marija Balic, Andrew Brenner, Amanda Fitzpatrick, Ian Krop, Megan Kruse, Zahi Mitri, Lajos Pusztai, Sara Tolaney, Manuel Valiente, Hans Wildiers. Presentations and discussions from this meeting provided the basis for the current manuscript. Figure 5 was created using BioRender.com. R, R. (2025). Retrieved from https://BioRender.com/yqkg64h.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization: N.U.L., K.J.J., E.D.R.; Data Curation: N.U.L., K.J.J., E.D.R.; Formal Analysis: N.U.L., K.J.J., E.D.R.; Investigations: N.U.L., K.J.J., E.D.R.; Methodology: K.J.J., E.D.R., E.A., P.K.B., M.E.G., E.S., C.P., N.U.L.; Project admin: N.U.L., E.D.R.; Resources: N.U.L., E.D.R.; Visualization: N.U.L., K.J.J., E.D.R.; Writing- original; N.U.L., K.J.J., E.D.R., Writing and editing: all authors. Graphics. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Artificial intelligence programs were not used in the writing of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.J.J. reports speaker/advisor board/consultant for: Amgen, AstraZeneca, Apo-biologix, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Esai, Genomic Health, Gilead Sciences, Knight Therapeutics, Merck, Myriad Genetics Inc, Pfizer, Roche, Novartis, Organon and research funding from: Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Pfizer. EDR reports Honoraria Astra Zeneca Servier Novartis, Conference Attendance support Gilead, Astra Zeneca, Integris, Servier, MSD, BMS, Pfizer, Genesis Pharma. AG reports Honoraria: Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Advisory Board: AstraZeneca Research grant to my Institution from Gilead, Support for attending medical conferences from: Novartis, Roche, Eli Lilly, Genetic, Instituto Gentili, Daiichi Sankyo, AstraZeneca. CA has received research funding PUMA, Lilly, Merck, Seattle Genetics, Nektar, Tesaro, G1-Therapeutics, ZION, Novartis, Pfizer, Astra Zeneca, Elucida, Caris, Incyclix, Beigene; she reports compensated consulting from: Genentech, Eisai, IPSEN, Seattle Genetics, Astra Zeneca, Novartis, Immunomedics, Elucida, Athenex, Roche; as well as Royalties from: UpToDate, Jones and Bartlett. PKB has consulted for ElevateBio, Genentech, Angiochem, Tesaro, Axiom Healthcare Strategies, InCephalo Therapeutics, Medscape, MPM Capital Advisors, Dantari, SK Life Sciences, Pfizer, CraniUS, Kazia, Sintetica, Voyager Therapeutics, Advise Connect Inspire and Atavistik, and has received research support (institution) from Merck, Mirati, Eli Lilly and Kinnate. NUL reports Institutional Research Support: Genentech, Pfizer, Merck, Seattle Genetics, Zion Pharmaceuticals, Olema Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Consulting Honoraria: Seattle Genetics, Daiichi-Sankyo, AstraZeneca, Olema Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Blueprint Medicines, Stemline/Menarini, Artera Inc., Eisai, Travel: Olema Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca. BL reports speaker/advisory board for Astra Zeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pfizer, Gilead, Eli Lilly, Stemline/Menarini and Novartis. FC reports consultancy role for Amgen, Astellas/Medivation, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Celgene, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GE Oncology, Genentech, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Iqvia, Macrogenics, Medscape, Merck-Sharp, Merus BV, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre-Fabre, prIME Oncology, Roche, Sanofi, Samsung Bioepis, Seagen, Teva, Touchime. E.G.E.de Vries reports Institutional Financial Support for her advisory role from Crescendo Biologics, Daiichi Sankyo and NSABP, and Institutional Financial Support for clinical trials or contracted research from Amgen, Genentech, Roche, Bayer, Servier, Regeneron and Crescendo Biologics, all outside the submitted work. CP reports consulting or advisory roles for, Daiichi Sankyo, Exact Sciences, Gilead, MSD, Menarini/Stemline Novartis, Pfizer and Seagen; research funding from, Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, Exact Sciences, Gilead and Seagen and travel support from, AZ, Gilead, Novartis, Pfizer and Roche. COS reports speaker/advisor board/consultant for: Pfizer, Astra Zeneca; Institutional Research Support: Pfizer, Sermonix and Bavarian Nordic.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jerzak, K.J., Razis, E.D., Agostinetto, E. et al. Novel treatment strategies and key research priorities for patients with breast cancer and central nervous system (CNS) metastases. npj Breast Cancer 12, 6 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00856-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00856-2