Abstract

Limited information is available for TP53 pathogenic variants (PVs) in early-onset breast cancer patients in China. We investigated the prevalence and clinical relevance of TP53 PVs among 1492 BRCA1/2-negative early-onset breast cancer patients. Peripheral blood samples were collected for TP53 genetic testing through next-generation sequencing. Finally, TP53 PVs were identified in 7 patients (0.47%). The variants p.R248P, p.I251F, and p.G266R were identified for the first time in germline mutations. TP53 carriers exhibited significantly younger diagnosis age (p = 0.003) and higher prevalence of HER2-positive disease (p = 0.020). All carriers were diagnosed before age 35. In HER2-positive patients ≤35 years, the prevalence of TP53 PVs was 2.3%, significantly higher than others after adjusting for a family history of breast cancer and/or ovarian cancer and a personal history of bilateral breast cancer (OR = 13.57, p = 0.002). These results support TP53 genetic testing prioritization for HER2-positive patients under 35 years to guide clinical management, while validation in diverse populations remains essential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The median age for breast cancer diagnosis in China is 47 years, which is at least 10 years younger than that in Western countries1,2. Early-onset breast cancer, defined as breast cancer diagnosed at age of 40 years or younger, accounts for >16% of cases, with an increasing trend in China1,2. In contrast, the prevalence of early-onset breast cancer in Western countries is significantly lower, ranging only from 4–6%. In other words, the population of early-onset breast cancer patients in China is substantial, roughly equivalent to the total number of early-onset breast cancer patients in Europe. Notably, young age at breast cancer diagnosis is usually considered associated with a higher frequency of carrying pathogenic variants (PVs) of breast cancer susceptibility genes3,4,5. The BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) genes are the dominant genes mutated in early-onset breast cancer and genetic testing for BRCA1/2 is recommended for all breast cancer patients with young onset. However, BRCA1/2 mutations are only responsible for 40–60% of hereditary breast cancer cases5,6,7, suggesting that other predisposing genes also play an important role in hereditary cases.

Though much rarer than BRCA1/2 mutations, pathogenic TP53 variants are associated with a high risk of breast cancer8,9. Previous studies has found that patients harbored TP53 PVs has higher risks of developing bilateral breast cancer, higher rates of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence after breast-conserving therapy, and even worse overall survival10,11,12. More importantly, TP53 PVs are strongly associated with Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS) or Li-Fraumeni-like (LFL) syndrome13,14, a rare autosomal dominant cancer predisposition syndrome characterized by an early age of onset and a high lifetime risk of multiple primary cancers, including early-onset breast cancer, osteosarcoma, soft tissue sarcoma, adrenocortical carcinoma, brain tumors, and leukemias. Once the first cancer develops, nearly half of patients develop another cancer after a median of 10 years15,16; thus, more attention is needed to monitor the occurrence of other primary cancers after breast cancer onset.

Studies on TP53 mutations in young breast cancer patients have been conducted in Western countries with a mutation rate rang from 0% to 12.1% depending on different ethnicities, age groups and sample sizes17,18. The POSH study identified 0.31% of TP53 carriers in a large early-onset breast cancer cohort of 2882 participants in the UK19, Couch et al. identified 0.40% TP53-carriers in 8009 early-onset patients in America20 and Giacomazzi et al. reported 12.1% TP53-carriers in 403 patients younger than 45 years in Brazil17. In contrast, research on the spectrum of TP53 mutations among young breast cancer patients in Asian populations is limited.

Given the epidemiological patterns of breast cancer susceptibility gene variants vary by race and space, the research on the spectrum of TP53 gene mutation among young breast cancer patients in China holds significant implications for this demographic. The identification of carriers of TP53 PVs among early-onset breast cancer patients is critical not only for the secondary prevention of breast cancer in patients but also for hereditary risk management in their relatives. In the face of a large number of early-onset breast cancer patients in China, which is a developing country, genetic testing for all young patients would impose a substantial healthcare burden. Information about the spectrum and characteristics of mutation carriers may guide the selection of appropriate individuals for genetic testing.

The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of germline PVs in TP53 among Chinese women with early-onset breast cancer who tested negative for BRCA1/2 PVs and to further explore the clinicopathological characteristics of mutation carriers to guide genetic testing strategies for young patients.

Results

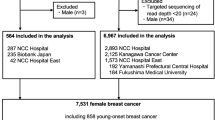

Characteristics of the patients screened for this study

A total of 1492 patients diagnosed with early-onset breast cancer between 2005 and 2023 and unselected for family history were screened for this study. The median age at diagnosis of first primary breast cancer was 36 years, ranging from 33–38 years, in the overall cohort. Additionally, 214 (14.3%) of the patients were diagnosed at age 30 years or younger, and 1278 (85.7%) were aged between 31 and 40 years. A family history of breast cancer and/or ovarian cancer was recorded in 98 (6.6%) patients. The majority of all young patients (70.6%, 1054/1492) were diagnosed with HR+ breast cancer; among them, 1031 patients had ER+ disease and 877 patients had PR+ disease. HER2+ breast cancer comprised 27.6% (412/1492) of the overall patient cohort. Invasive ductal carcinoma is the most common pathological type (83.9%). More details of the baseline characteristics of the overall patient cohort are displayed in Table 1.

PVs identified in patients with early-onset breast cancer

Seven patients (0.47%) carried TP53 PVs, including four pathogenic variants (p.R175H, p.R248P, p.G266R and p.E286K), two pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants (p.R273C and p.R337C), and one likely pathogenic variant (p.I251F) (Table 2). All variants were missense mutations and identified only once for each. No other types of mutations, including nonsense, indels, and splice variants, were detected. Notably, 43% (3/7) of the mutations were identified for the first time in germline mutations, including p.R248P, p.I251F, and p.G266R.

Associations of demographic characteristics with PVs

The median age at diagnosis was 30 years among patients harboring TP53 PVs, which was significantly younger than the 36 years among non-carriers (p = 0.003). The prevalence of TP53 PVs was 1.9% (4/214) among patients at or below age 30, which was significantly higher than 0.23% (3/1278) at age 31–40 (p = 0.010) (Table 1). TP53-carriers had a higher likelihood of a positive family history of breast cancer and/or ovarian cancer than non-carriers (28.6% vs. 6.5%), while the difference was close to statistical significance for TP53 PVs (p = 0.072). Only one TP53-carrier was diagnosed with bilateral breast cancer (14.3%, p = 0.197) (Tables 1 and 3).

None of the seven TP53-carriers met classic LFS criteria, while four met the Chompret 2015 of breast cancer diagnosis age younger than 31 years without other LFS-related tumors or a family history suggestive of LFS, and only one met the criteria of Chompret 2009 (c.796 G > A, p.G266R), who had tibial sarcoma at age 17 years and was diagnosed with unilateral breast cancer at age 33 years, and the proband’s father was diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndrome at age 55 years (Fig. 1).

Associations of clinical characteristics with PVs

TP53 PVs were enriched among HER2-positive breast cancer (71.4%), significantly higher than HER2-negative breast cancer (28.6%, p = 0.020). Likewise, patients diagnosed with HER2-positive breast cancer also had a higher frequency of TP53 PVs (5/412, 1.2%) than HER2-negative breast cancer patients (2/1080, 0.19%). Furthermore, the most common molecular subtype among TP53 carriers was HER2 + /HR- (3/7, 42.9%), followed by HER2 + /HR+ (2/7, 28.6%) and HER2-/HR+ (2/7, 28.6%), and none of the TP53 carriers was TNBC (p = 0.044) (Table 1 and Table 3).

In addition, among patients with HER2-positive disease, TP53 PVs were identified in 4 of 68 (4.4%) patients aged 30 years or younger, 2 of 150 (1.3%) patients aged 31–35 years, and none of 194 (0%) patients aged 36–40 years. In total, TP53 PVs accounted for 4.4% (3/68) of patients aged 30 years or younger, 2.3% (5/218) of patients aged 35 years or younger, and 1.2% (5/412) of patients aged 40 years or younger (Table 4). Given that 40% (2/5) of HER2-positive TP53 carriers were between the ages of 31 and 35 years, we further analyzed the subgroup mutation risk in patients at or younger than 35 years, rather than 30 years, compared with others in this early-onset cohort. After adjusting for a family history of breast cancer and/or ovarian cancer and a personal history of bilateral breast cancer, the prevalence of TP53 PVs was significantly increased in HER2-positive patients with a diagnosis age of 35 or younger (OR 13.57, p = 0.002).

Invasive ductal carcinoma was observed in all 7 TP53 PV carriers (Table 1). Patients carried TP53 PVs were weakly associated with more aggressive pathological features than non-carriers, including higher histologic grade (57.1% vs. 35.0%), larger tumor size (71.4% vs. 55.3%), and higher Ki-67 index (85.7% vs. 75.0%), although the differences were nonsignificant (Table 1).

Discussion

Given that the large population of young breast cancer patients remains a substantial health burden for China and the limited data available for TP53 PVs of that population, we investigated the germline TP53 PVs with data derived from 1492 patients with early-onset breast cancer unselected for family history to inform efficient strategies for genetic testing. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date that provides insight into the prevalence and clinical characteristics of TP53 PVs in early-onset breast cancer in China.

Seven patients were found to be carriers of TP53 PVs with mutation rates of 0.47% in this study, which was lower than 1.0% reported by Sheng et al. in the corresponding age subgroups of another large unselected breast cancer cohort in China11, but slightly higher than the rate of 0.31% in UK19 and 0.40% in America20. Additionally, given the rare mutation frequency of 0.47% among our early-onset breast cancer cohort, the onset age contributed limited to TP53 gene testing.

One of the variants detected in this study is TP53 1009 C > T (p.R337C), a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant commonly associated with LFS. It should be noted that this variant differs from p.R337H (TP53 1010 G > A)17, a variant that has been identified in 12.1% of patients diagnosed with breast cancer at or before age 45, regardless of their family history of cancer. The p.R337H is identified as a founder mutation in the Brazilian population, representing 70.3% of all TP53 PVs in Brazil21. However, no recurrent variants were found in our study. Although the identification of founder mutations allows targeted detection of single mutations and saves testing costs, current research has not found any founder mutations in the Chinese population.

Among the variations detected in this study, p.R175H is a hotspot of TP53 PVs among breast cancer and LFS patients in both Western and Asian populations11,22. Specifically, while codons 248 and 273 are acknowledged TP53 hotspots11,16,22, with p.R248Q, p.R248W, and p.R273H mutations frequently reported, our cohort uniquely identified p.R248P mutations within these codons, and p.R273C has not been previously reported in breast cancer patients. Additionally, p.R248P, p.I251F had not been identified in breast tumors before and are also being reported for the first time as germline mutations. The p.G266R mutation was identified as a somatic mutation in breast tumor specimens in a Japanese study23, and it has not been previously reported as a germline mutation. Our research findings revealed the specific TP53 PVs in Chinese patients with early-onset breast cancer and reflected the necessity of investigating diverse populations to better understand unique genetic variations.

In previous studies, the frequencies of TP53 PVs among patients aged 30 years or younger were ranging from <2%–8%16,18,24,25,26. In our study, the mutation rate of TP53 PVs in the corresponding population was 1.9%, which is found to be significantly higher than the frequency in breast cancer patients aged 31–40 years (p = 0.01). The comparison underscored the higher propensity for TP53 PVs in the patients with younger age.

Some previous studies have found a significant association between TP53 PVs and bilateral breast cancer9,11,20,27, leading to the recommendation of bilateral mastectomy for affected patients28,29. Furthermore, Couch et al. reported that TP53 PVs were only associated with a family history of ovarian cancer, but not with a family history of breast cancer in a larger nationwide sample of unselected breast cancer20. Conversely, Siraj et al. did not observe any association between TP53 PVs and family history of breast cancer or any cancer among early onset Middle Eastern breast cancer patients27. In our current study, we did not find a significant association between TP53 PVs and personal history of bilateral breast cancer or family history of breast cancer and/or ovarian cancer. This suggests that these two factors may not be appropriate decision criteria for TP53 genetic testing in younger patients.

Sheng et al. indicated that breast cancer patients with germline TP53 mutations have a poorer prognosis compared to non-carriers11. Additionally, TP53 carriers are at an increased risk of developing radiation-induced secondary malignancies after adjuvant radiotherapy25,28. Consequently, mastectomy may be more appropriable for TP53 carriers to avoid the need for radiotherapy following breast-conserving surgery. The decision to use radiotherapy post-mastectomy also warrants careful consideration. The European Reference Network for Genetic Tumour Risk Prediction (GENTURIS) guidelines emphasize the importance of identifying TP53 carriers before the initiation of treatment to potentially avoid radiotherapy in carriers30. Moreover, asymptomatic carriers in the families of TP53 mutation patients face a significantly increased risk of cancer, necessitating regular surveillance, particularly in pediatric carriers25,29. Therefore, the identification of TP53 carriers among breast cancer patients not only aids in optimizing treatment strategies for patients but also enhances cancer surveillance in at-risk family members.

In clinical practice, BRCA1/2 gene testing is recommended for young breast cancer patients, with emphasis on testing for HER2-negative patients because it accounts for the majority of BRCA1/2 PVs. However, the majority of TP53 carriers were HER2-positive patients (71.4%) in our study, consistent with 67%–83% from previous studies31,32. Consistent with the majority of previous studies, our research found a significant association between TP53 mutations and HER2-positive status31,32,33. Compared to HER2-negative disease, patients with HER2-positive status have a significantly higher frequency of TP53 PVs (1.2%) in the whole cohort, similar to the 1.4%-1.5% found in previous studies of early-onset patients6,33. In addition, we observed that the prevalence of TP53 PVs in HER2-positive patients aged 35 years or younger was 2.3%, which is approximately 13 times higher than that of the remaining cohort after adjustment for family history and personal history of bilateral breast cancer. Although the prevalence of TP53 PVs can be as high as 4.4% in HER2-positive patients aged 30 years or younger, it should be highlighted that 40% of TP53 PVs occurred in patients between age 31 and 35 years old, which should not be omitted. Consequently, our findings recommend that TP53 genetic testing could serve as a crucial supplement for HER2-positive patients with early-onset, particularly in patients younger than 35 years old.

There are some limitations to our study. First, although this study has the largest sample size of patients with early-onset breast cancer to date, the rare mutation rate of breast cancer susceptibility genes led to a limited number of identified carriers, potentially reducing the statistical power of our analyses. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, this study focused on Chinese patients with early-onset breast cancer. Due to the regional and ethnic specificity of genetic mutations, the TP53 mutation spectrum observed in this cohort may not be generalizable to other populations, and further validation is needed. Second, although we collected LFS-related family history for individuals carrying TP53 mutations, we did not collect such information for all study participants, which may have limited our ability to comprehensively evaluate the association between TP53 mutations and LFS-associated malignancies. Third, long-term follow-up was not available for all individuals, and the survival data were immature. Previous studies have reported that TP53 carriers have a high rate of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence after breast-conserving surgery18. Therefore, further prognostic analysis is necessary to estimate the impact of different treatment options on survival in PV carriers and non-carriers, so as to offer optimal management for carriers. Finnally, this study did not include a control group of young individuals who are not affected by breast cancer, limiting our ability to evaluate the risk for the development of early breast cancer in young carriers of TP53 PVs.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the prevalence of TP53 PVs were 0.47% in the largest early-onset breast cancer cohort in China. TP53 PVs are significantly associated with younger age at diagnosis and HER2-positive status. Multivariate logistic regression results indicated that the prevalence of TP53 PVs was significantly increased in HER2-positive patients with a diagnosis age of 35 or younger; thus, we emphasized that target TP53 genetic testing needs to be considered in that population.

Methods

Study population and data collected

In a cohort of women with early-stage breast cancer diagnosed at Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (Fuzhou, China) between 2005 and 2023, patients who met all the following eligibility requirements were screened for the study: (1) diagnosis of breast cancer at age 40 or younger; (2) confirmation of invasive breast cancer by histopathology; and (3) negativity for BRCA1 and BRCA2 PVs. All the procedures performed in studies involving human participants adhered to the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Demographic data, including age at first diagnosis of breast cancer, sex, personal history of breast cancer and family history of breast cancer and/or ovarian cancer, were obtained by face-to-face questionnaires during their clinic visits. A positive family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer is defined as having one or more first- or second-degree relatives with a history of breast or ovarian cancer. The criteria for LFS and LFL syndrome were determined with reference to the classical LFS criteria and the 2009 and 2015 versions of the Chompret criteria14,16,34.

Clinical data, including tumor size, lymph node status, histologic type, histologic grade, and immunohistochemical characteristics, were extracted from medical records. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was used to detect the presence of the estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR). Nuclear staining in >10% of cells was used as the criterion to define ER-positive (ER + ) and PR-positive (PR + ) cases. Hormone receptor (HR)-positive cases were defined as ER+ and/or PR+ cases. Immunohistochemical staining with a score of 3+ and/or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) amplification of the human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) gene was used to identify HER2-positive (HER2 + ) cases.

DNA extraction and NGS

Peripheral blood samples were obtained from patients at the time of breast cancer diagnosis, and whole blood genomic DNA was subsequently isolated. Sequencing of all coding regions and exon‒intron boundaries of the TP53 genes was performed through NGS (Illumina NovaSeq) by Shanghai AITA Genetics Technology Co., Ltd and AmoyDx Biomedical Technology Co., LTD. The sequencing results were then aligned to the TP53 (NM_000546.5) sequences using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) tool. Base quality score recalibration, indel realignment, and variant calling were performed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK). All the variants were annotated with ANNOVAR (http://www.openbioinformatics.org/annovar/) and subsequently validated by Sanger sequencing. Novel mutations were identified by excluding variants with a population frequency >0.1% in the gnomAD and ExAC databases and confirming their absence in ClinVar (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) and the IARC TP53 database (p53.iarc.fr/). The pathogenicity of mutations was predicted using PolyPhen-2 and SIFT, and variants were classified according to the ClinVar and American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) criteria35. Both pathogenic and likely pathogenic mutations were recorded as PVs in this study.

Statistical analysis

The Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables were performed to compare characteristics between pathogenic mutation carriers and non-carriers. Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine the risk factors for mutation carriers and calculate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). A difference was considered statistically significant if the p-value was <0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with R software (version 4.3.0). WPS Office (version 12.1.0) were used to create the pedigree charts.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Guo, R. et al. Changing patterns and survival improvements of young breast cancer in China and SEER database, 1999−2017. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 31, 653–662 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Trends in disparities and transitions of treatment in patients with early breast cancer in China and the US, 2011 to 2021. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2321388 (2023).

Franco, I. et al. Genomic characterization of aggressive breast cancer in younger women. Ann. Surg. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-023-14080-4 (2023).

Buys, S. S. et al. A study of over 35,000 women with breast cancer tested with a 25-gene panel of hereditary cancer genes. Cancer 123, 1721–1730 (2017).

Momozawa, Y. et al. Germline pathogenic variants of 11 breast cancer genes in 7,051 Japanese patients and 11,241 controls. Nat. Commun. 9, 4083 (2018).

Breast Cancer Association Consortium et al. Pathology of tumors associated with pathogenic germline variants in 9 breast cancer susceptibility genes. JAMA Oncol. 8, e216744 (2022).

Susswein, L. R. et al. Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variant prevalence among the first 10,000 patients referred for next-generation cancer panel testing. Genet. Med. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 18, 823–832 (2016).

Easton, D. F. et al. Gene-panel sequencing and the prediction of breast-cancer risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2243–2257 (2015).

Fu, F. et al. Association between 15 known or potential breast cancer susceptibility genes and breast cancer risks in Chinese women. Cancer Biol. Med. 19, 253–262 (2021).

Hyder, Z. et al. Risk of contralateral breast cancer in women with and without pathogenic variants in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 genes in women with very early-onset (<36 Years) Breast Cancer. Cancers 12, 378 (2020).

Sheng, S. et al. Prevalence and clinical impact of TP53 germline mutations in Chinese women with breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer 146, 487–495 (2020).

Guo, Y. et al. Risk of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence and contralateral breast cancer in patients with and without TP53 variant in a large series of breast cancer patients. Breast Edinb. Scotl. 65, 55–60 (2022).

Li, F. P. & Fraumeni, J. F. Soft-tissue sarcomas, breast cancer, and other neoplasms. A familial syndrome?. Ann. Intern. Med. 71, 747–752 (1969).

Li, F. P. et al. A cancer family syndrome in twenty-four kindreds. Cancer Res. 48, 5358–5362 (1988).

Mai, P. L. et al. Risks of first and subsequent cancers among TP53 mutation carriers in the national cancer institute Li-fraumeni syndrome cohort. Cancer 122, 3673–3681 (2016).

Bougeard, G. et al. Revisiting Li-fraumeni syndrome from TP53 mutation carriers. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 2345–2352 (2015).

Giacomazzi, J. et al. Prevalence of the TP53 p.R337H mutation in breast cancer patients in Brazil. PLoS ONE 9, e99893 (2014).

Rogoża-Janiszewska, E. et al. Prevalence of germline TP53 variants among early-onset breast cancer patients from Polish population. Breast Cancer Tokyo Jpn. 28, 226–235 (2021).

Copson, E. R. et al. Germline BRCA mutation and outcome in young-onset breast cancer (POSH): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 19, 169–180 (2018).

Couch, F. J. et al. Associations between cancer predisposition testing panel genes and breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 3, 1190–1196 (2017).

Guindalini, R. S. C. et al. Detection of germline variants in Brazilian breast cancer patients using multigene panel testing. Sci. Rep. 12, 4190 (2022).

Wasserman, J. D. et al. Prevalence and functional consequence of TP53 mutations in pediatric adrenocortical carcinoma: a children’s oncology group study. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 602–609 (2015).

Takahashi, M. et al. Distinct prognostic values of p53 mutations and loss of estrogen receptor and their cumulative effect in primary breast cancers. Int. J. Cancer 89, 92–99 (2000).

Lalloo, F. et al. BRCA1, BRCA2 and TP53 mutations in very early-onset breast cancer with associated risks to relatives. Eur. J. Cancer 42, 1143–1150 (2006).

Blondeaux, E. et al. Germline TP53 pathogenic variants and breast cancer: a narrative review. Cancer Treat. Rev. 114, 102522 (2023).

Mouchawar, J. et al. Population-based estimate of the contribution of TP53 mutations to subgroups of early-onset breast cancer: Australian breast cancer family study. Cancer Res. 70, 4795–4800 (2010).

Siraj, A. K. et al. Prevalence of germline TP53 mutation among early onset middle eastern breast cancer patients. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 19, 49 (2021).

Alyami, H. et al. Clinical features of breast cancer in South Korean patients with germline TP53 gene mutations. J. Breast Cancer 24, 175–182 (2021).

Schon, K. & Tischkowitz, M. Clinical implications of germline mutations in breast cancer: TP53. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 167, 417–423 (2018).

Frebourg, T., Bajalica Lagercrantz, S., Oliveira, C., Magenheim, R. & Evans, D. G. Guidelines for the Li–fraumeni and heritable TP53-related cancer syndromes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 28, 1379–1386 (2020).

Melhem-Bertrandt, A. et al. Early onset HER2 positive breast cancer is associated with germline TP53 mutations. Cancer 118, 908 (2012).

Wilson, J. R. F. et al. A novel HER2-positive breast cancer phenotype arising from germline TP53 mutations. J. Med. Genet. 47, 771–774 (2010).

Rath, M. G. et al. Prevalence of germline TP53 mutations in HER2+ breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 139, 193–198 (2013).

Gonzalez, K. D. et al. Beyond Li fraumeni syndrome: clinical characteristics of families with p53 germline mutations. J. Clin. Oncol. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 27, 1250–1256 (2009).

Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet. Med. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 17, 405–424 (2015).

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to all participants. We thank Prof. Chunfu Zheng for editing our manuscript. This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2020J01995), and the joint funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian Province (2018Y9205, 2019Y9103).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L.: data curation, writing of the main manuscript text, collection of the blood samples and clinical information; L.L.C.: planning and design of the study, resources, recruitment of the patients, collection of the blood samples. X.H.C. and M.H.: Data curation. M.Y.C., W.H.G. and Y.X.L.: Recruiting the patients, collection the blood samples. Y.L.W., W.F.C., Y.B.Q., P.H. and Q.D.C.: collection clinical information. F.M.F. and C.W.: planning and design of the study, resources, project administration, recruitment of the patients. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (2020KJT031). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

Patient consent for publication

Consent to publish has been obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Chen, L., Chen, X. et al. Clinical TP53 genetic testing is recommended for HER2-positive breast cancer patients aged 35 or younger. npj Genom. Med. 10, 53 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-025-00496-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-025-00496-2