Abstract

The Genomic Medicine for Everyone (Geno4ME) study was established across the seven-state Providence Health system to enable genomics research and genome-guided care across patients’ lifetimes. We included multi-lingual outreach to underrepresented groups, a novel electronic informed consent and education platform, and whole genome sequencing with clinical return of results and electronic health record integration for 78 hereditary disease genes and four pharmacogenes. Whole genome sequences were banked for research and variant reanalysis. The program provided genetic counseling, pharmacist support, and guideline-based clinical recommendations for patients and their providers. Over 30,800 potential participants were initially contacted, with 2716 consenting and 2017 having results returned (47.5% racial and ethnic minority individuals). Overall, 432 (21.4%) had test results with one or more management recommendations related to hereditary disease(s) and/or pharmacogenomics. We propose Geno4ME as a framework to integrate population health genomics into routine healthcare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Genetic variants contribute to the risk of various common adult disorders in the US, such as heart disease, diabetes, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases1,2,3,4. These variants include both common alleles with low additive impact3 and rare but highly penetrant variants. High-risk variants in genes related to inherited cancers and cardiomyopathies are considered actionable by the American College of Medical Genetics & Genomics (ACMG)5.

Many individuals are unaware of their genetic risks until a disorder manifests6,7,8. For example, over 90% of people with a pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) variant for BRCA-associated cancers, Lynch syndrome, or familial hypercholesterolemia discover these variants after developing the condition, with only 25% having a known family history8. Additionally, a significant portion of individuals with P/LP variants do not meet the criteria for genetic testing9 or are not offered testing despite meeting National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) guidelines10.

Population genetic screening could enhance the identification of individuals at increased genetic risk, leading to early disease detection and prevention. Testing for pharmacogenomics (PGx) can also improve treatment outcomes and reduce adverse drug reactions (ADRs). For instance, a study projected that 99% of US veterans have at least one actionable genetic result per Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines11, which could help in reducing ADRs for many conditions12. Despite these benefits, adoption of genetic screening for inherited disease and PGx remains infrequent due to challenges such as lack of integration with electronic health records (EHR), insufficient provider and patient familiarity with genomic medicine, and genetic assays costs13,14,15.

A promising strategy for overcoming these challenges is the use of whole genome sequencing (WGS), which can be analyzed for new genetic indications over time. Recent advancements, such as AI-enabled data analysis and decreasing WGS costs, present an opportunity for healthcare systems to implement precision health initiatives. Combining WGS data with clinical data and risk factors such as family history, health behaviors, and social determinants of health can aid in identifying individual genetic risks and support population genetic research.

While some health systems have used intensive provider engagement to recruit patients for genomic screening, this approach may not be scalable in diverse health systems, particularly with decentralized management. Additionally, national population genomic screening efforts such as the NIH All of Us Research Program operate largely outside a patient’s clinical care team and lack a direct pathway to patient care.

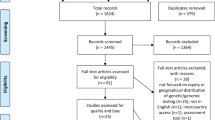

Providence is one of the largest US community health systems with more than 50 hospitals and 1000 clinics across seven states and over 30,000 providers, many of whom are independent clinicians. Providence implemented the “Genomic Medicine for Everyone” (Geno4ME) study to screen for high-impact clinical variants using WGS. We focused on cancer, cardiovascular disease, and PGx variants, providing guideline-based clinical recommendations for identified P/LP variants (Fig. 1 and Tables 1, 2). For example, participants with increased cancer risk receive early detection and preventive recommendations based on NCCN Guidelines®16,17. Similarly, specific guideline-based recommendations were provided for participants with P/LP variants in any of the 59 genes determined to be clinically actionable and reportable by the ACMG for secondary findings5. Although the ACMG does not endorse this list specifically for population-based screening, the conditions included are considered of sufficient medical necessity to report as part of any broad research or clinical whole genome testing8,18. Here we report our initial study results as well as suggestions for future genome-enabled healthcare.

This figure illustrates the different steps of the Geno4ME study. It espcially highlights the two different recruitment approaches (population outreach and clinic invitation), the DNA sequencing/analysis workflow, and the return of results for positive results. Created in BioRender. Dowdell, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/j66k266.

Results

Enrollment and demographics

From March 2021 to April 2023, potential Providence participants in seven states received population outreach (N = 27,787) or were invited through clinics (N = 3091) (Tables 3 and 4). By June 2023 (end of the sample return period), 2716 had consented to the study (8.8% overall enrollment). Compared to clinic invitation, individuals consented through population outreach were more racially and ethnically diverse (57.2% vs 9.2% self-identified as racial or ethnic minorities), younger (39.5% vs 23.9% ≤ 45 years old), and more likely to be male at birth (30.7% vs 20.6%) (Table 5). The clinic sample was reflective of the local population.

Of the 2716 participants who consented, 2092 (77.0%) provided at least one blood and/or saliva sample, and 2017 (74.3%) had sequencing completed and received a clinical results report. Of the 699 (25.7%) who did not receive results, 624 did not send a sample, and 75 had failed sequencing due to insufficient DNA (QNS) for WGS. Among the 75, 22 were true technical failures (21 provided 2 samples, and 1 provided 3 samples), and 53 did not return a second sample after the first failed.

Enrollment was higher for clinic-based outreach (15.4%) than for population outreach (7.6%). However, a chi-square test of independence found no significant difference in sample return rates between outreach types (X2(1) = 0.40, p = 0.525); 75.9% (1611) of the population outreach participants and 77.9% (145) of the clinic-based participants who were mailed a saliva kit returned their samples. Amongst patients recruited from a clinic, we also found no significant difference in sample return rates between enrollment clinic types (one specialty clinic versus two primary care clinics; 45% and 55% of the phase 2 clinic-based cohort, respectively) (X2(1) = 0.32, p = 0.572).

To identify possible equity issues in home saliva sample collection, we tested for an association between sample return and participant race and ethnicity within the population outreach cohort, as the clinic cohort was mostly White (90.8%). A chi-square test of independence found a significant association between race and ethnicity and sample return (X2(5) = 17.40, p = 0.004). Post-hoc analyses of standardized residuals with a Bonferroni correction showed Hispanic participants were less likely to return a sample than the population outreach cohort as a whole (69% vs 76%, p = 0.006), while White participants had a higher return rate (80%, p = 0.009).

WGS assay validation of the inherited disease and pharmacogenomics gene panels

For inherited disease genes, accurate detection of single nucleotide variants (SNVs), indels, and copy number variants (CNVs) by WGS was validated using orthogonal panel testing at a commercial reference laboratory (N = 188 participants) and known positives/reference materials (N = 61) (J.T.W., J.W., I.A.L.B., K.R.E., B.A.C., K.O., N.W., Tucker C. Bower, L.C.Y., E.M.S., K.J., J.C., A.T.M., M.B.C., O.K.G., C.B.B., and B.D.P., in review). Using the commercial laboratory as a reference, the Geno4ME WGS assay had 100% sensitivity and specificity for detecting P/LP SNVs, indels, and SVs (N = 188 participants). Variant calling from paired blood and saliva samples was 100% concordant for detecting P/LP and variants of unknown significance (VUS) variants (N = 60 matched participants).

For the PGx panel, we observed 100% concordance for CYP2C19, CYP2C9, VKORC1, and CYP4F2 when comparing our training set results with the GeT-RM (CDC Genetic Testing Reference Material program) data for 18 Coriell samples sequenced (J.T.W., J.W., I.A.L.B., K.R.E., B.A.C., K.O., N.W., Tucker C. Bower, L.C.Y., E.M.S., K.J., J.C., A.T.M., M.B.C., O.K.G., C.B.B., and B.D.P., in review). Additionally, we observed 100% concordance for CYP2C19, CYP2C9, VKORC1, and CYP4F2 when blood or saliva samples were tested using orthogonal panel testing at a commercial reference laboratory (N = 188 participants). PGx results from paired blood and saliva samples were 100% concordant using the Geno4ME method (N = 60 matched participants). Since rs12777823 (CYP2C cluster), a PGx marker for the drug warfarin, was not included in the GeT-RM or Invitae Laboratories PGx panels, the BAM files of the 188 validation set samples were visually inspected to confirm the genotyping results and quality.

Reportable findings and return of results

21.4% (432/2017) of participants who received a test report had one or more medical intervention recommendations (inherited disease or PGx).

Inherited disease gene panel findings

In total, 158/2017 (7.8%) of participants who received a report had at least one clinically significant finding (P/LP classified variant) associated with an inherited disease, and five individuals had two findings (Fig. 2). Despite previous reports of a higher VUS rate in US minority racial and ethnic populations that could limit the identification of actionable results19, a chi-square test of independence found no significant association between participant race and ethnicity and the clinical significance of the results (Fig. 3).

The top box recapitulates the number of participants who consented, provided at least one DNA sample, and received their clinical report (i.e., had sequencing completed). For the 2017 participants who received a clinical result report, the two bottom boxes provide the number of reports with at least one pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) finding (left green box) or no P/LP finding (right light gray box). The P/LP findings are grouped by type of associated disease. The number (percentage) of participants who self-reported during enrollment personal or family history of the associated disease that would meet (or not meet) the threshold for detailed risk assessment and genetic counseling is indicated for each group of participants (cancer or cardiovascular disease only). Created in BioRender. Dowdell, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/y24s275.

This bar graph shows the race and ethnicity distribution of the 158 participants (dark green) who had one or more P/LP variant (positive finding) for one of the genes associated with an inherited disease and of the 1859 participants (light green) who had no P/LP finding. The percentages are calculated within each group (i.e., with or without a positive finding).

Three participants were double heterozygous for P/LP variants in two different genes: (1) BRCA2 and CHEK2, (2) ATM and LDLR, and (3) ATP7B and KCNH2. Two participants were compound heterozygous for variants in ATP7B, but the variants could not be phased due to the base pair distances exceeding read length. A total of 163 P/LP variants were identified (Fig. 4, see Supplementary Table 1 for a complete list of reported variants, classification, and associated disease). Most positive findings (91/163, 55.8%) were in cancer-associated genes, with MUTYH (30 participants, 19%, all heterozygous) and CHEK2 (18, 11%) being the most common. Of these 18 P/LP findings in CHEK2, 7 were the I157T variant, which at time of study had clinical recommendations for high-risk screening20,21, but is now considered a risk allele without specific recommended management changes22,23. Similarly, at the time of results delivery, MUTYH heterozygotes had recommendations for enhanced colorectal cancer screening20, but most recent NCCN Guidelines22 no longer recommend increased screening. These findings were thus characterized as “carrier risk”. While NBN was initially listed in our panel as associated with an increased risk for certain cancers, including breast, NCCN Guidelines stopped recommending increased breast cancer screening for carriers of an NBN P/LP variant. Therefore, NBN P/LP variants were returned solely for Nijmegen breakage syndrome reproductive risk (See Supplementary Table 1), and the test report indicated that while certain NBN P/LP variants were previously associated with increased cancer risk, recent studies did not support this, and current guidelines have no screening recommendations. For ATP7B, two individuals were compound heterozygotes but lacked the phenotype associated with Wilson disease, thus considered non-penetrant but at risk.

This bar graph displays the number of pathogenic and likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants identified in genes associated with increased risk of cancer (total N = 100, with 60 variants associated with an increased risk for the participants in medium blue, and 40 identified as carrier risk only in light blue), cardiovascular and connective tissue diseases (total N = 31, with 27 variants associated with an increased risk for the participants in medium green, and 4 identified as carrier risk only in light green), and other (total N = 32, with 4 variants associated with an increased risk for the participants in dark blue, and 28 identified as carrier risk only in very dark blue). In total, 163 P/LP were identified and confirmed by the external reference laboratory. Of note, for VHL, one variant (in light blue) was only associated with autosomal recessive erythrocytosis and polycythemia, for APOB, 3 variants (light green) were associated with hypobetalipoproteinemia, and for LMNA, 1 variant was associated with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome and mandibuloacral dysplasia type A (light green).

Reproductive risk was not a primary endpoint, but, given the iterative NCCN risk guidelines, 71 (44.7%) participants received results solely associated with reproductive or carrier risk (including 30 with a P/LP variant in MUTYH, 5 in NTHL1, 2 in MSH3, 2 in NBN, 1 in VHL associated specifically with erythrocytosis and polycythemia, 3 in APOB associated with hypobetalipoproteinemia, 1 in LMNA associated with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome and mandibuloacral dysplasia type A, 7 in RYR1, and 20 in ATP7B). Excluding these 71 participants and those with asymptomatic Wilson disease genotype, 45/86 (52%) test-positive participants had no self-reported history meeting criteria for genetic counseling referral (Fig. 2). For most, the lack of personal disease history could be explained by the participant’s age and/or sex at birth (Table 6). Conversely, 47% (883) and 20% (379) of participants without a positive inherited disease risk had personal and/or family histories of cancer and cardiovascular disease, respectively, meeting genetics referral thresholds. A chi-square test of independence found no significant association between having a P/LP variant and meeting referral thresholds, neither for cancer (X2(2) = 4.09, p = 0.129) nor for cardiovascular disease (X2(1) = 0.06, p = 0.806).

PGx findings

A PGx finding was defined as a potentially actionable result if the participant was taking one of the supported medications (Table 2) at enrollment and had a PGx result indicating increased risk of side effects or decreased efficacy (see Supplementary Table 2 for a complete list of all the reported diplotypes/genotypes and associated phenotypes). Of participants who received results, 294/2017 (14.6%) had a potentially actionable PGx finding (one participant had two findings). Most of these findings were related to proton pump inhibitors (82%, N = 242), followed by antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs, 13%, N = 39), and anticoagulants/antiplatelet agents (5%, N = 14). All participants received a PGx report with at least one recommendation for future care management for the seven frequently prescribed drugs included in the panel (Fig. 5).

The bar graph shows, for each self-reported race and ethnicity, the percentage of participants who received 1 (dark green), 2 (medium green), 3 (lighter green), or 4 (lightest green) PGx-guided recommendations in their Geno4ME clinical report. The number of identified PGx recommendations per participant reported in this graph is regardless of their answer to the medication questionnaire from enrollment.

Return of results follow-up

All providers received their patients’ results through an electronic EHR notification, including a cover letter and a link to the provider portal with additional clinical resources (gene-specific “Just In Time” documents). Providers of participants with positive inherited disease results were also notified by a study coordinator. Of the 158 participants with a P/LP variant, 154 were referred to genetic counseling services covered by the study, while 4 declined as they were already being followed by clinical genetics. Utilization of telehealth genetic counseling services via Genome Medical was exceptionally high (Table 7). There were no significant differences in demographics between all referred individuals and those who completed the genetic counseling appointment (Supplementary Table 3). Cancer risks and screening vary by gene, sex, and age (Fig. 6). For our participants with a positive finding in a cancer gene, the recommendations for clinical interventions include enhanced screening (such as breast MRI, MRCP for pancreatic cancer); preventive medication with a selective estrogen modulator, aspirin, or oral contraception; endoscopy (EGD endoscopic ultrasound, colonoscopy) or consideration of risk reducing surgery (oophorectomy, bilateral mastectomy). High risk genes with lifetime risk over 40% or over 10fold general population risk included BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CDKN2A, MLH1, MSH6, PALB2, RAD51C, RAD51D, SDHB, TP53, and VHL; moderate risk genes with lifetime risk over 20% were ATM, PMS2, and CHEK2 (other than I157T), or with recommendation for earlier colonoscopy initiation for MUTYH. The low penetrant reported findings were the APC I1307K and the CHEK2 I157T variants. Notably, participants with an MUTYH finding comprised 63% of the moderate risk category and 2/3 of those with an enhanced screening. Furthermore, 40% of participants with an enhanced screening recommendation carried either a P/LP MUTYH variant or the CHEK2 I157T variant. For participants with familial hypercholesterolemia, all were recommended to have complete lipid panels and PCSK9 inhibitors if elevated cholesterol. Because cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias can present at any age, all 14 participants were referred to cardiology for comprehensive exam and echo or electrophysiology testing as appropriate. For participants with a potentially actionable PGx result(s), 39 (13.3%) resulted in a therapy adjustment(s), including dose modifications, discontinuation of medications, or switching to alternative therapies, after PGx pharmacist consultation.

For the 89 participants who had a positive finding associated with an increased risk of cancer, the bar graph shows the breakdown of participants with either enhanced screening/risk reduction recommendation (dark blue) or no screening/intervention (light blue) for each of the three cancer risk categories (high risk genes: BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CDKN2A, MLH1, MSH6, PALB2, RAD51C, RAD51D, SDHB, TP53, and VHL; moderate risk genes: ATM, MUTYH, PMS2, and CHEK2, and low penetrant genes/variants: APC I1307K and CHEK2 I157T. One participant had a P variant in BRCA2 and the CHEK2 I157T variant and is counted twice (90 P/LP variants in total).

Discussion

Genomic medicine is now at a point where increased sequencing speed, cost reduction, and scalable cloud platforms can enable population-scale clinical sequencing. As eighty-four percent of US hospitals are community hospitals (AHA Fast Facts on US hospitals, 2024)24, integrating genomics into community healthcare represents a significant opportunity for greater genomic access. To deliver on this promise, programs must be scalable, efficient, and equitable. With Geno4ME, we aimed to recruit diverse populations, establish WGS for clinical assessment, develop scalable digital research tools requiring minimal on-site clinic staff, and educate patients and providers. Given Providence’s breadth as a community health system and the challenges this posed, we offer lessons learned from the project.

We made efforts to reach racial and ethnic minority groups, including Hispanic, Black, or Asian; those with Medicaid coverage; rural residents; and Spanish primary language speakers25. Our enrolled population comprised 47.5% who self-identified as racial or ethnic minorities and spanned across five Western states (CA, OR, WA, MT, and AK)25. Since the study was launched during the COVID-19 pandemic, we developed novel consent and biospecimen collection methods to enable participation from home. While previously established US population genomics programs have successfully recruited patients for genomics biorepositories and results return, most have multiple limitations, including heavy dependence on “warm touch” recruitment by on site research personnel and on-site consent and sample collection as well as being limited to a single state or region (Geisinger MyCode, Healthy Oregon, Healthy Nevada, Sanford Chip, Intermountain Heredigene), or lack of connection to direct clinical care (NIH All of Us Research Program)8,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33.

In Geno4ME, despite provider outreach supporting clinic-based recruitment, achieving recruitment from multiple clinics across our multi-state community health system was less efficient than direct patient outreach with supplementary provider education. The “direct-to-patient” approach had lower enrollment compared to clinic-based recruitment (7.6% vs. 15.4%), but it was scalable, reached younger and more diverse patients, and resulted in similar sample return rates and genetic counseling participation25. Reaching younger populations is crucial, as screening for CDC Tier 1 conditions is cost-effective in individuals under 4034. We observed that Hispanic individuals were less likely to return samples while White participants were more likely to do so. Future studies should explore reasons for this and understand why individuals may decide not to enroll, especially when directly outreaching to a diverse population. These may include distrust in research, lack of perceived results importance, preferred language, etc. However, collecting that information is challenging when using an online approach, and we are exploring qualitative studies, such as in-depth telephone interviews, to inform future interventions. Additionally, because outreach initiation in WA, MT, and AK was done later than in CA and OR, their recruitment numbers are lower, but engagement patterns were similar in all regions.

All consenting took place via a custom-built e-consent platform, with no paper forms or in-person visits. Our results suggest population-based outreach can recruit a broad population for genetic screening. While a trusted provider may motivate initial participation, provider involvement did not significantly impact genetic testing completion. Future programs should develop resources to help providers discuss genetic testing and counseling benefits with patients. Multiple opportunities to hear about genetic testing from trusted sources may enhance patient involvement.

Our return-of-results panel included genes associated with cancer, cardiovascular disease, and pharmacogenomics. For inherited diseases, we curated a panel with moderate penetrance genes defined in NCCN Guidelines and those recommended by the ACMG as secondary findings in whole genome studies. Pathogenic gene variants were detected in 7.7% of participants. 1.44% of participants received a report with a P/LP variant associated with a CDC Tier 1 condition, comparable to the Healthy Nevada project (1.33%) and the Geisinger MyCode project (1.27%)8,18. Our inherited disease panel also included conditions that could present late onset and recessive conditions, where heterozygous carriers may also have moderate risks. Moderate risk genes on this panel are subject to continued changes in risk interpretation. For example, recent NCCN Guidelines have changed screening recommendations for MUTYH and NBN heterozygotes and the CHEK2 I157T variant22,24. Programs including moderate-risk genes should convey newly modified risk information. Our platform incorporates continuous communication and genetic counseling referral for changing risk interpretations. It brings forward two critical needs for any population testing program: (1) the ability to be able to recontact participants as clinical interpretation updates and (2) given the evolving nature, particularly of hereditary cancer genes risk estimations, any population-based program must be adequately prepared to manage changing guidelines. Narrow population screening, such as limiting to CDC Tier 1, would not eliminate this need, as recommendations are also dynamic, such as new recommendations to screen ALL BRCA2 carriers for pancreatic cancer over age 5023. Furthermore, a very limited panel would miss a critical opportunity to discover risks in a much broader population. However, we believe any genes included or excluded should be given careful consideration and consensus on decision based on levels of evidence. We relied on the NCCN Guidelines as actionable for hereditary cancer. Unfortunately, these guidelines are frequently revised, meaning our communication to participants about their results requires modifications and additional notification. This presents a marked potential for over screening when including moderate risk genes (like MUTYH) and high frequency low penetrance variants (such as APC I1307K and CHEK2 I157T). However, in our population, this would have resulted at most, in recommendation for potentially one additional colonoscopy. There is no “bright line” for inclusion or exclusion of any given moderate risk gene since the converse holds true as well. The newest NCCN guideline has again reduced the age of breast cancer MRI initiation from 40 to age 30 for the CHEK2 1100delC. We recommend genomic sequencing programs returning adult-pertinent screening findings consider avoiding conditions like ATP7B, or return only specific disease-associated variants, and have a streamlined pathway for high-frequency variants in specific populations, like that of MUTYH and CHEK2.

We observed P/LP variants in 52% of participants with no reported personal or family history of the associated disease (cancer or cardiovascular disease). While patients with personal or family disease history might be more interested in genomic screening, other initiatives found that 35–75% of participants reported no relevant history before receiving a genetic diagnosis8,28. This suggests potential inconsistencies in how patients report disease histories and how histories are clinically documented. A proactive population testing approach may be effective alongside family history-based screening methods. Though many participants in our study reported a history of cancer or cardiovascular disease, this was based on self-report, not formal pedigree collection or EHR data. Future programs should also address empirical risks for individuals with no P/LP variant but positive histories. Incorporation of polygenic scores may further personalize risk assessment, especially for patients with reported family history but no positive findings35.

Considering the seven commonly prescribed drugs included in the panel, every patient had at least one genotype that could affect their current or future care, with 14.6% having a potentially actionable result. Therefore, we recommend including PGx data in future population genomic screening programs. Manual pharmacist medication reconciliation was successful for PGx-guided therapy recommendations, but not scalable36. We have implemented clinical decision support software in our EPIC EHR for managing PGx data and providing useful information at the time of ordering. Our preliminary results suggest high provider use of PGx-recommended therapy adjustments.

A key element of our program is the change in patient care due to increased access to genetic testing and integration of results into routine clinical care. There is much to be learned on how population-level genetic screening ultimately impacts health care utilization and outcomes, especially when the screening is performed before conditions develop37,38. In the next phase of our research, we will bring together participant clinical records and 12- and 24-month longitudinal participant surveys that include validated measures of health and health care utilization. In addition, we will assess participants’ understanding of their genetic testing results and cascade testing for family members to determine how these screenings ultimately impact outcomes in the diverse Geno4ME population.

To date, we have no reported insurance denials for Geno4ME recommended screening or care changes. In addition, we have not been informed of any participant undergoing risk-reducing surgery following results disclosure. Longitudinal follow-up will be needed to assess clinical impact, disease risk modification, and health costs. The 12- and 24-month surveys and EHR data extraction will help us detect such changes. Specific questions about coverage, costs, and access are included in the 12- and 24-month surveys. Utilization of telehealth genetic counseling services was high among participants with P/LP variants, which may have been facilitated by our re-test education and post-test follow-up.

Return of results was not integrated into the EHR as discrete data but as PDF reports in the “Media” tab. We have implemented the EPIC Genomic Indicator Module (EGIM) to store Geno4ME results discretely for better visibility. However, genome portability in healthcare remains an issue. Longitudinal follow-up of participants is ongoing, collecting data on health behaviors, outcomes, and the relationship between genomic and social determinant risk factors. Health economic outcomes will be analyzed in future surveys. Our program serves as a model for facilitating patient-provider genomic dialogues through continued updates, building a base for accessible genomic medicine.

Though Geno4ME involved thousands of patients across multiple states, participants had to be established within the Providence Health system, which could introduce selection bias as compared to national programs like the All of Us Research Program. However, Providence is not a closed system, and participants could have any form of health insurance, from private, managed care, or federal programs, thus reflecting the broader US national healthcare landscape. The overall enrollment rate (15.4% clinic-based, 7.6% virtual) mirrors other studies. Despite the promise of free WGS testing and access to counseling and education, barriers to engagement remain, likely driven by perceived value, connection between genomics and routine care, apprehension about findings, and data privacy concerns. The nature of this outreach and remote consent did not allow for assessment of declination to enroll, which was a significant limitation to our study and the opportunity to improve engagement. Future work will focus on understanding these barriers and developing strategies to overcome them. Though technology fluency could limit participation, over 85% of Americans own smartphones (Pew Research Center, Mobile and Internet, Broadband Fact Sheets)39,40. Our clinic-based recruitment was limited and opportunistic rather than stratified random sampling. Future studies should consider stratified random sampling within eligible clinic populations.

Methods

Participant eligibility

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Providence IRB (approval number STUDY2020000637). All participants were over the age of 18 and a current Providence patient with one or more visits with a Providence provider in the previous 12 months. Participants provided the name and contact information for their primary Providence provider, who would receive the lab report. All racial and ethnic backgrounds were eligible; however, due to limitations in educational and consent materials, initial enrollment was restricted to English or Spanish speakers who could enroll online. Participants were required to have a current, viable email, mailing address, and telephone number. Participants were excluded if they were pregnant, had a history of bone marrow transplantation, or had an active hematologic malignancy.

Participant outreach and recruitment

Figure 1 describes the participant process starting from initial outreach. Between March 2021 and April 2023, eligible Providence patients were invited to participate in Geno4ME (https://www.geno4me.org). Participants could return their sample kits until June 30, 2023. There were two invitation pathways: a clinic-centered outreach for assay and process validation in three clinics in Oregon (OR), California (CA), and Washington (WA) (March-September 2021), and a direct-to-patient outreach using stratified random sampling in five states (OR, CA, WA, Alaska (AK), and Montana (MT)) within the Providence system (population outreach) (September 2021 onward). Outreach began in CA and OR in September 2021 due to the large number of eligible patients and expanded to WA, MT, and AK in May 2022.

Clinic-based recruitment involved identifying patients with upcoming appointments. These patients received a MyChart invitation from a research coordinator or clinic staff two weeks before their appointment or a flyer during their visit. To increase participation of underrepresented populations in genomic studies, we used population-level stratified random sampling focusing on patients of Asian, Black, and Hispanic ancestry, Spanish speakers, and Medicaid patients (as a proxy for socioeconomic status and healthcare vulnerability). Recruitment outreach used mail, email, text messages, and auto calls in English and Spanish25.

Enrollment process

Participants could enroll in Geno4ME online using a novel e-consent platform designed by Providence. This platform included genetic testing information, frequently asked questions (FAQ) guides, and a step-by-step consent process with pre-enrollment educational videos (Fig. 1). The platform was the first comprehensive e-consent process of its kind approved by Providence. Participants were asked to create a study account to access the e-consent platform, choose their preferred language (English or Spanish), and sign consent documents. Study accounts allowed participants to answer surveys privately and securely, access their genetic report and consent document, receive post-enrollment education, and change their status regarding future research participation opportunities.

During enrollment, participants completed a brief survey about their personal/family medical history. This information was used to generate a tailored report cover letter for primary care physicians, informing them of participant-reported history that warranted formal evaluation. The responses were not used for variant curation. The survey included questions on race and ethnicity (see Supplementary Table 4), self-reported personal and family history of cancer and cardiovascular disease, and current use of any of the seven PGx medications included in the genetic screen. Personal and family history questions were based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines and Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) consensus statements to determine if patients met the threshold for detailed risk assessment and genetic counseling.

Sample collection

Sample collection was divided into two phases: Phase 1 involved both blood and saliva samples for WGS assay validation with a limited number of participants. Phase 2 used mailed saliva collection kits only, designed to be more scalable, easier for participants and clinic staff, and to mirror a true population-based approach. Ultimately, 88.7% of all study participants were part of Phase 2.

Phase 1 sample collection

To validate our Geno4ME assay and processes, Phase 1 involved collecting blood and saliva samples at a clinic encounter by local staff. A phlebotomist at the clinic or a Providence laboratory collected 8–10 mL whole blood in standard EDTA tubes and 5 mL in standard PPT Pearl tubes. Saliva was collected using an Oragene Saliva DNA Collection kit (DNA Genotek) (2 mL). All collection tubes were labeled with participant information as required by CLIA and CAP regulations. Specimens were transferred via courier (in Oregon) or FedEx overnight shipping at room temperature to the Providence Molecular Genomics Laboratory (MGL; Portland, Oregon, CLIA #38D2032720, CAP #8034828). In September 2021, after validating the assay and process, all enrollment channels transitioned to the Phase 2 saliva-based population outreach sample collection workflow.

Phase 2 sample collection

In Phase 2, all enrolled participants received an Oragene Saliva DNA Collection kit (DNA Genotek) sent directly to their residence, auto-generated by our study platform. Participants collected their saliva sample (2 mL) at home and mailed it at room temperature to the Providence MGL using approved regulatory and postage-paid packaging. If a participant’s primary saliva sample failed, they were asked to provide a blood sample at a Providence phlebotomy station. Blood samples were collected in 8–10 mL EDTA tubes and transferred via courier (within Oregon) or FedEx overnight shipping to the Providence MGL.

WGS-based assay workflow and validation process

DNA extraction from blood or saliva was performed using the QIAsymphony DSP Midi Kit on a QIAsymphony instrument (Qiagen). WGS libraries were prepared from 300 to 500 ng of gDNA with the Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep, Tagmentation kit and sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq 6000. Genomic secondary analysis for the genes included in the Geno4ME test was performed using standard analysis pipelines on the Illumina DRAGEN (Dynamic Read Analysis for GENomics) Bio-IT Platform.

A validation set of 188 DNA samples (119 whole blood, 69 saliva, with 60 paired blood/saliva specimens) from newly enrolled patients, known positives, and control reference materials was used for assay validation along with orthogonal testing at a CLIA/CAP commercial molecular laboratory (Invitae). A training set of 18 DNA samples from the CDC Genetic Testing Reference Material program (GeT-RM) was used in addition to the blood/saliva DNA patient samples for validation of the PGx results41. These 18 samples were sequenced at MGL following the same procedure as the participant DNA samples.

Variant curation and confirmation

Initial variant prioritization and scoring were performed using the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant Fabric Genomics cloud platform42. For PGx, pre-selected variants were genotyped, and phenotypes were assigned in the Fabric Genomics platform based on Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base (PharmGKB), Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC), and Pharmacogene Variation Consortium (PharmVar) annotations43,44,45. For inherited diseases, single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), multi-nucleotide variants/polymorphisms (MNVs), insertions, deletions, and copy-number variants (CNVs) were automatically annotated and classified using the Automated Variant Classification Engine (ACE) from Fabric Genomics. ACE scores variants based on the 2015 guidelines for variant interpretation from ACMG and the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP)46, which uses evidence from public databases such as ClinVar47, dbSNP, and gnomAD to classify and prioritize variants.

Variants were initially classified if ACE provided enough ACMG criteria to assign a pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) or benign/likely benign (B/LB) classification. Variants where ACE could not provide enough criteria and/or those with a ClinVar interpretation of P, LP, conflicting, or not provided were prioritized for manual review. CNV pathogenicity classification was performed based on recommendations by Riggs et al. (2020)48. Prior to curation, variants of interest identified by ACE (i.e., P/LP variants, certain prioritized VUS, and CNVs) were visually inspected using Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) for alignment quality and evidence of variant phasing49. Curation and final assignment of these variants were completed in-house by Clinical Scientists using the 2015 ACMG guidelines and the Mastermind literature search engine46,50. Variants classified as P/LP were included in the clinical report, while those classified as VUS or B/LB were not returned to participants. After final review, the presence of P/LP variants associated with inherited diseases was independently confirmed by Invitae using an orthogonal NGS process (Fig. 1).

Geno4ME return of results panel design

As part of Geno4ME enrollment, clinically actionable genetic results were reported back to participants and their designated providers to guide clinical decisions. Study consent required agreeing to the return of results; participants could not “opt out.” While WGS was performed, the data analyzed for the return of results was limited to genes selected for assessing inherited disease risk and PGx. All other genome regions outside the scope of the Geno4ME return of results were bioinformatically masked for the team preparing the clinical interpretation and report.

For inherited diseases, the gene panel included clinically relevant genes with well-established disease associations, especially for cancer and cardiovascular disease, where knowledge of the pathogenic variant warrants medical recommendations. The panel included the 59 genes identified by the ACMG as relevant secondary findings from sequencing (ACMG 59)5, and 18 additional genes with actionable management recommendations by the 2021 NCCN Guidelines for genetic/familial cancer risk (Table 1)20,21.

For PGx, the panel included seven gene-drug pairs selected based on FDA and CPIC guidelines, prescription usage data across the Providence St. Joseph Health (PSJH) system, and race and ethnicity data (Table 2; FDA, Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labeling)51,52,53,54. PGx variants were pre-selected based on the published joint recommendations from the AMP and the CAP, as well as CPIC guidelines. For CYP2C19, both Tier 1 (*2, *3, and *17) and Tier 2 (*4 A, *4B, *5, *6, *7, *9, *10, and *35) alleles were included per AMP/CAP recommendation55. As recommended by the CPIC guideline for warfarin, CYP2C9 Tier 1 alleles (*2, *3, *5, *6, *8, and *11), VKORC1 (c.-1639G > A, rs9923231), CYP4F2 (*3), and the single variant rs12777823 (CYP2C cluster) were initially included56,57.

For the variant analysis, a 5000 bp buffer region on both sides of each gene of both panels was included. For three genes, GREM1, EPCAM, and PMS2, the analyzed regions were expanded further to include large known duplications and deletions58.

Return of results process to participant and provider

Results were electronically returned to participants, their providers, and genetic counselors when appropriate (Fig. 1). Positive inherited disease results were indicated by the presence of any P/LP variant(s) in the 77 panel genes. The I1307K variant within the APC gene was reported as associated with “moderate colorectal cancer” only. VUS, LB, and B variants were not reported for the inherited disease panel. The results report included a cover letter to providers explaining: (1) the study purpose, (2) if any P/LP variant(s) had been identified, and (3) any reported personal or family history of cancer or cardiovascular conditions associated with inherited disease risk, which might warrant further genetic counseling referral (Supplementary Data 1). The report also included links to a Geno4ME provider portal with educational material, including 1–2-page, gene-specific “Just In Time” information sheets summarizing clinical risks, condition management recommendations, and participant next steps (Supplementary Data 2). This portal was created and hosted by study partner and telehealth counseling provider, Genome Medical (GM) (Supplementary Data 3). For participants seen by a GM genetic counselor, providers were sent the participant’s personalized action plan generated during their counseling appointment.

Participants with a positive panel disease result were contacted by a Providence research coordinator by phone and/or email to disclose initial results and arrange a GM genetic counseling consultation appointment. After this visit, participants and their providers received a personalized care plan from the GM genetic counselor. Personalized care plans for hereditary cancer were based on the NCCN guidelines version for Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic as well as Colorectal at the time of return of results and tailored for sex-based risk, screening initiation and frequency, and risk-reducing medication and surgery options as relevant. A clinical note was created following the standard genetic counseling visit format after a complete review of personal medical and family history. Participants with negative results but a positive personal or family history on screening questions received a cover letter recommending further risk evaluation. For cardiovascular disease, recommendations were based on AHA guidelines for hyperlipidemia, cardiomyopathy, and rhythm disorders. Participants with a potentially actionable PGx genotype/phenotype for drugs reported at enrollment were offered a pharmacist consultation. Following the consultation, any recommended medication changes were shared with their provider. The Geno4ME provider portal also included “Just In Time” clinical decision support material based on CPIC guidelines for the seven gene-drug pairs.

If the participant did not respond after six outreach attempts (phone and/or email), results were automatically provided through MyChart and their Geno4ME participant portal. The participant was then given resources to schedule genetic counseling for a personalized care plan in the future.

Research data management and biorepository

In addition to the Geno4ME clinical report, participants consented to the storage and approved researchers’ use of aggregate de-identified data to support research into genetic disease risks and clinical, family history, health behavior, and social risk factors. Upon enrollment, each participant was assigned a unique Subject ID Number by Providence’s HIPAA-compliant, cloud-based platform for patient education, engagement, and consent. Geno4ME resources (processed WGS data including binary alignment map [BAM] and variant call format [VCF] files, survey responses, and clinical EHR extracts) were de-identified, tagged with the MPT-generated Subject ID Number, and stored in an encrypted cloud-based infrastructure.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square tests of independence were performed in R version 4.3.1 to assess associations between categorical variables59. Where race and ethnicity were analyzed as a combined variable, the “Other” racial and ethnic category was excluded because of too few instances. Post hoc analyses of standardized residuals with a Bonferroni correction were conducted where needed to further characterize any significant associations using the “chisq.posthoc.test” R package60.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to protocol and Informed Consent language that mandate our IRB to review projects and require a data use agreement (DUA), but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All P/LP variants are listed in supplemental data and have been externally validated for reproducibility and interpretation of variant call.

Code availability

DRAGEN v 3.9.5 is available at https://support-docs.illumina.com/SW/DRAGEN_v39/Content/SW/FrontPages/DRAGEN.htm. IGV v.2.11.1 is available at https://software.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/download. Fabric Enterprise v.6.6.8 – v.6.6.12 are available from Fabric Genomics Inc.

References

McPherson, R. & Tybjaerg-Hansen, A. Genetics of coronary artery disease. Circ. Res. 118, 564–78 (2016).

Langenberg, C. & Lotta, L. A. Genomic insights into the causes of type 2 diabetes. Lancet 391, 2463–2474 (2018).

Mavaddat, N. et al. Polygenic risk scores for prediction of breast cancer and breast cancer subtypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 104, 21–34 (2019).

Fernando, M. B., Ahfeldt, T. & Brennand, K. J. Modeling the complex genetic architectures of brain disease. Nat. Genet. 52, 363–369 (2020).

Kalia, S. S. et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2.0): a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet. Med. 19, 249–255 (2017).

Beitsch, P. D. et al. Underdiagnosis of hereditary breast cancer: are genetic testing guidelines a tool or an obstacle?. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 453–460 (2019).

Nordestgaard, B. G. et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur. Heart J. 34, 3478–90a (2013).

Grzymski, J. J. et al. Population genetic screening efficiently identifies carriers of autosomal dominant diseases. Nat. Med. 26, 1235–1239 (2020).

Samadder, N. J. et al. Comparison of universal genetic testing vs guideline-directed targeted testing for patients with hereditary cancer syndrome. JAMA Oncol. 7, 230–237 (2021).

Manahan, E. R. et al. Consensus guidelines on genetic‘ testing for hereditary breast cancer from the American Society of Breast Surgeons. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 26, 3025–3031 (2019).

Chanfreau-Coffinier, C. et al. Projected prevalence of actionable pharmacogenetic variants and level a drugs prescribed among US Veterans Health Administration pharmacy users. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e195345 (2019).

Swen, J. J. et al. A 12-gene pharmacogenetic panel to prevent adverse drug reactions: an open-label, multicentre, controlled, cluster-randomised crossover implementation study. Lancet 401, 347–356 (2023).

Caudle, K. E., Hoffman, J. M. & Gammal, R. S. Pharmacogenomics implementation: “ a little less conversation, a little more action, please. Pharmacogenomics 24, 183–186 (2023).

Braveman, P. & Gottlieb, L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 129, 19–31 (2014).

Singh, G. K. & Jemal, A. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in cancer mortality, incidence, and survival in the united states, 1950-2014: over six decades of changing patterns and widening inequalities. J. Environ. Public Health 2017, 2819372 (2017).

Benson, A. B. et al. Colon cancer, version 1.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 15, 370–398 (2017).

Bevers, T. B. et al. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis, version 3.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl Compr. Canc Netw. 16, 1362–1389 (2018).

Kelly, M. A. et al. Leveraging population-based exome screening to impact clinical care: the evolution of variant assessment in the Geisinger MyCode research project. Am. J. Med. Genet. C. Semin. Med. Genet. 187, 83–94 (2021).

Ndugga-Kabuye, M. K. & Issaka, R. B. Inequities in multi-gene hereditary cancer testing: lower diagnostic yield and higher VUS rate in individuals who identify as Hispanic, African or Asian and Pacific Islander as compared to European. Fam. Cancer 18, 465–469 (2019).

Weiss, J. M. et al. NCCN guidelines® insights: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, version 1. J. Natl Compr. Canc Netw. 19, 1122–1132 (2021).

Daly, M. B. et al. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian, and pancreatic, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 19, 77–102 (2021).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal (Version 2.2023). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_colon.pdf (2023).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic: Colorectal (Version 3.2024). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_bop.pdf (2024).

American Hospital Association. Fast Facts on US hospitals. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2024/01/fast-facts-on-us-hospitals-2024-20240112.pdf. Accessed 7/11/2024 (2024).

Dickey, L. et al. Participation in genetic screening: testing different outreach methods across a diverse hospital system based patient population. Front. Genet. 14, 1272931 (2023).

David, S. P. et al. Implementing primary care mediated population genetic screening within an integrated health system. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 34, 861–865 (2021).

Wildin, R. S., Giummo, C. A., Reiter, A. W., Peterson, T. C. & Leonard, D. G. B. Primary care implementation of genomic population health screening using a large gene sequencing panel. Front. Genet. 13, 867334 (2022).

Buchanan, A. H. et al. Clinical outcomes of a genomic screening program for actionable genetic conditions. Genet. Med. 22, 1874–1882 (2020).

Lemke, A. A. et al. Patient-reported outcomes and experiences with population genetic testing offered through a primary care network. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomark. 25, 152–160 (2021).

Carey, D. J. et al. The Geisinger MyCode community health initiative: an electronic health record-linked biobank for precision medicine research. Genet. Med. 18, 906–13 (2016).

Lemke, A. A. et al. Primary care physician experiences with integrated population-scale genetic testing: a mixed-methods assessment. J. Pers. Med. 10, 165 (2020).

Denny, J. C. et al. The “All of Us” research program. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 668–676 (2019).

Christensen, K. D. et al. Precision population medicine in primary care: the Sanford chip experience. Front. Genet. 12, 626845 (2021).

Guzauskas, G. F. et al. Population genomic screening for three common hereditary conditions: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann. Intern Med. 176, 585–595 (2023).

Elson, S. L. et al. The Athena Breast Health Network: developing a rapid learning system in breast cancer prevention, screening, treatment, and care. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 140, 417–25 (2013).

Yuan, L. C. & Beckett Lucas, I. P418: a genome sequencing approach to pharmacogenomic profiling across diverse population in a large health system. Genet. Med. Open 1, 100454 (2023).

Brothers, K. B., Vassy, J. L. & Green, R. C. Reconciling opportunistic and population screening in clinical genomics. Mayo Clin. Proc. 94, 103–109 (2019).

Peterson, J. F. et al. Building evidence and measuring clinical outcomes for genomic medicine. Lancet 394, 604–610 (2019).

Pew Research Center. Mobile Fact Sheet. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/. Accessed 7/11/2024 (2024).

Pew Research Center. Internet, Broadband Fact Sheet. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/. Accessed 7/11/2024 (2024).

Pratt, V. M. et al. Characterization of 137 genomic DNA reference materials for 28 pharmacogenetic genes: a GeT-RM collaborative project. J. Mol. Diagn. 18, 109–23 (2016).

Coonrod, E. M., Margraf, R. L., Russell, A., Voelkerding, K. V. & Reese, M. G. Clinical analysis of genome next-generation sequencing data using the Omicia platform. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 13, 529–40 (2013).

Whirl-Carrillo, M. et al. An evidence-based framework for evaluating pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 110, 563–572 (2021).

Caudle, K. E. et al. Standardizing terms for clinical pharmacogenetic test results: consensus terms from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC). Genet. Med. 19, 215–223 (2017).

Gaedigk, A., Casey, S. T., Whirl-Carrillo, M., Miller, N. A. & Klein, T. E. Pharmacogene variation consortium: a global resource and repository for pharmacogene variation. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 110, 542–545 (2021).

Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 17, 405–24 (2015).

Landrum, M. J. et al. ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D980–D985 (2014).

Riggs, E. R. et al. Technical standards for the interpretation and reporting of constitutional copy-number variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen). Genet. Med. 22, 245–257 (2020).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 24–26 (2011).

Chunn, L. M. et al. Mastermind: a comprehensive genomic association search engine for empirical evidence curation and genetic variant interpretation. Front. Genet. 11, 577152 (2020).

Hicks, J. K. et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and dosing of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 98, 127–34 (2015).

Lima, J. J. et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline for CYP2C19 and proton pump inhibitor dosing. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 109, 1417–1423 (2021).

Scott, S. A. et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for CYP2C19 genotype and clopidogrel therapy: 2013 update. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 94, 317–23 (2013).

Food and Drug Administration. Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labeling. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/science-and-research-drugs/table-pharmacogenomic-biomarkers-drug-labeling Accessed 7/11/2024 (2024).

Pratt, V. M. et al. Recommendations for clinical CYP2C19 genotyping allele selection: a report of the Association for Molecular Pathology. J. Mol. Diagn. 20, 269–276 (2018).

Pratt, V. M. et al. Recommendations for clinical CYP2C9 genotyping allele selection: a joint recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology and College of American Pathologists. J. Mol. Diagn. 21, 746–755 (2019).

Johnson, J. A. et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline for pharmacogenetics-guided warfarin dosing: 2017 update. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 102, 397–404 (2017).

Kuiper, R. P. et al. Recurrence and variability of germline EPCAM deletions in Lynch syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 32, 407–14 (2011).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 7/11/2024 (2023).

Ebbert D. chisq.posthoc.test: A Post Hoc Analysis for Pearson’s Chi-Squared Test for Count Data. R package version 0.1.2. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=chisq.posthoc.test. Accessed 7/11/2024 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Genome Medical for their advisory services on initial program and actionable findings panel design and development of customized gene-specific fact sheets, as well as Invitae for orthogonal confirmation and Fabric Genomics for WGS tertiary analysis/initial variant interpretation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was written by I.A.L.B. and K.R.E., with critical input from O.K.G. and B.D.P. The study was designed by the five principal investigators, O.K.G., C.B.B., A.T.M., B.D.P., and K.V., with support from J.C., E.D., K.R.E., K.J., I.A.L.B., J.C.L., E.R., and K.T. Project administration was led by J.C., K.R.E., M.B.C., and JBR., as well as M.G.R. for Fabric Genomics. Editorial and revision assistance were provided by J.M.S. The study data were analyzed by I.A.L.B. and J.T.W. with support from K.R.E. The recruitment material was designed by I.A.L.B., K.J., K.R.E., and JBR.; I.A.L.B., K.J., and K.R.E. worked on provider/patient education material. The front-end portion of the study website and the e-consent were developed by L.A. and A.K. created all the graphics and designs for the education and recruitment material. L.D. and K.G.J. designed the population outreach recruitment strategy with oversight by K.V. and provided some data analysis. N.W., K.J., I.A.L.B., and K.R.E. designed the clinical report with the support from J.T.W. The curation of the variants for inherited diseases was done by I.A.L.B. and J.T.W.; I.A.L.B. developed the PGx test panel, and K.O. developed the PGx variant caller in the Fabric Genomics cloud platform. J.T.W. and J.W. performed the WGS test validation and routine WGS. J.W., with support from M.M.M. and M.J.R., oversaw the variant confirmation process with the external laboratory. M.B.C. and B.D.P. oversaw the sequencing lab operation. B.A.C. and E.M.S. provided bioinformatic support. B.S. and H.V. created and maintained the participant database with oversight by A.T.M. PGx pharmacist consults to participants and providers were conducted by L.C.Y. The graphical design of the figures and the abstract was done by A.K.D. Statistical analysis was performed by B.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.T. is a current employee of Illumina, but during her involvement with the study, she was affiliated with ISB. E.R. was an employee of and shareholder in Genome Medical, Inc. Genome Medical was paid to consult on this project and is a paid provider for the gene-specific fact sheets and telehealth genetic counseling. M.G.R. is a founder, employee, and shareholder of Fabric Genomics. K.O. is the founder and employee of Genetic Intelligence Inc. and works as a consultant for Fabric Genomics.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lucas Beckett, I.A., Emery, K.R., Wagner, J.T. et al. Geno4ME Study: implementation of whole genome sequencing for population screening in a large healthcare system. npj Genom. Med. 10, 50 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-025-00508-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-025-00508-1

This article is cited by

-

Establishing a biospecimen repository of diverse populations in a network healthcare organization

Discover Health Systems (2026)