Abstract

Personalized precision dosing remains an unmet clinical need. This study used population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) modeling to evaluate transitioning lacosamide (LCM) in children with epilepsy from body weight (BW)-based (mg/kg) to simplified BW-band or fixed-dose (mg) regimens. Real-world data from 190 patients were analyzed using nonlinear mixed-effects modeling program, comparing a BW-based model (Model I) and a genotype-guided model (Model II); the latter showed superior predictive performance. Monte Carlo simulations confirmed comparable LCM exposure across regimens, with >78% target attainment in external validation. A fixed 100 mg dose for patients ≥10 kg achieved equivalent exposure to BW-adjusted dosing, with consistent results in 1–4 years and obese patients. These findings enabled BW-band dosing as a clinically viable alternative to mg/kg regimens, while CYP2C19 genotyping further enhanced precision. This PopPK-based strategy simplifies LCM therapy without compromising efficacy, offering a practical approach to personalized epilepsy management in children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lacosamide (LCM), a third-generation antiseizure medication (ASM), is approved for the treatment of focal seizures in patients aged ≥1 month and for primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures in patients aged ≥4 years1. Its unique mechanism—selective enhancement of sodium channel slow inactivation—enables effective seizure control with favorable pharmacokinetics, including linear kinetics and low protein binding2,3. Recent studies have further revealed its efficacy and tolerability in children, supporting its growing use in this population4,5,6. However, some patients continue to experience suboptimal or unsuccessful seizure control, and the underlying factors contributing to this variability remain poorly understood. Key drivers include interindividual differences in LCM’s exposure due to body weight (BW), age, CYP2C19 polymorphisms, and drug-drug interactions (DDIs). Moreover, evidence is very limited for special cases such as patients who are obese and those aged 1–4 years3,7,8,9.

In pediatric pharmacotherapy, BW-adjusted dosing (e.g., mg/kg) is commonly used. Compared to fixed dosing (e.g., mg), this approach may experience the following disadvantages in clinical practice: increased complexity and risk of dosing errors; challenges posed by frequent BW fluctuations and special considerations for obese or underweight children; difficulty in dose splitting and measurement inaccuracies with liquid formulations; as well as problems with treatment adherence and safety concerns. Fixed or BW-band dosing offers a promising solution to these challenges by simplifying administration and reducing variability. However, the feasibility of these approaches remains uncertain. Addressing this gap is critical to ensure that alternative dosing strategies could achieve comparable therapeutic outcomes while minimizing risks.

Therapeutic drug monitoring is one of the effective strategies to assess whether dose tailoring meets therapeutic requirements. If both the efficacy and adverse effects of a drug are deemed acceptable within a defined concentration range, this range can then serve as a basis to evaluate different dosing regimens10. In such cases, population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) models become particularly useful. We hypothesized that LCM administered via BW-adjusted (mg/kg) and fixed (mg) dosing regimens could achieve comparable exposure levels to LCM, enabling the selection of more practical dosing approaches. PopPK studies may provide robust model validation data to support this hypothesis. Indeed, existing studies on PopPK models have made active efforts to explore individualized dose adjustments for LCM11,12,13,14,15. Yet, no research has attempted to investigate the hypothesized shift in dosing regimens from BW-adjusted administration to fixed-dose medication proposed in our assumption.

Herein, we aimed to: (1) develop PopPK models to evaluate the feasibility of fixed or BW-band dosing as alternatives to BW-adjusted regimens; and (2) provide PopPK-based dosing recommendation shift for special populations, including obese children and those aged 1–4 years. By leveraging PopPK modeling, this study seeks to simplify the LCM dosing while maintaining therapeutic concentrations, ultimately improving outcomes for children with epilepsy.

Results

Study population

This study included 190 cases with 493 plasma LCM concentration measurements, which were divided into a model development group (133 patients, 347 LCM concentrations) and a validation group (57 patients, 146 LCM concentrations).

The LCM concentration range was 0.70–11.90 μg/mL in the model development group and 1.16–10.30 μg/mL in the validation group, with mean concentrations of 3.71 μg/mL and 3.76 μg/mL, respectively.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the included cases are summarized in Table 1. No significant differences were observed between the model development and validation groups in terms of age, BW, or sex. Additional subject characteristics used for PopPK modeling are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Model development

The pharmacokinetics of LCM were adequately described by a one-compartment model with first-order absorption and elimination, consistent with previous study15. Two final models were developed: Model I (only BW data) and Model II (integrated BW and CYP2C19 genotype data). Detailed PopPK modeling results are provided in Supplementary Material S4.4.

In Model I, interindividual variability (η-shrinkage) in CL/F and V/F was estimated using exponential models, and residual variability (ε-shrinkage) was best described by a mixed error model (Supplementary Eq. 7), which yielded the lowest objective function value (OFV) and akaike information criterion (AIC). Covariate screening revealed that BW significantly improved the model (a change in OFV (ΔOFV) = 38.332, p < 0.001) and was retained in the final model. Although several covariates—including serum creatinine (SCR), sodium channel blockers (SCBs), potassium (K), red blood cell count (RBC), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC)—significantly influenced CL/F during forward inclusion (ΔOFV > 3.84, p < 0.05), none were retained during backward elimination (ΔOFV < 10.83, p > 0.001). The changes in OFV during covariate screening for Model I are summarized in Supplementary Table S4.

The final model I was as follows:

The typical CL/F of LCM in children with epilepsy at steady state was 1.51 L/h/kg, consistent with previously reported values (1.4–2.4 L/h/kg)12,13,15. The Vd/F was 23.7 L, aligning with prior findings (0.6 L/kg).

In Model II, CYP2C19*2 rs12769205 significantly influenced CL/F (ΔOFV = 16.465, p < 0.001), while BW remained the most impactful covariate (Supplementary Table S5). The final Model II was described as:

where θrs12769205 = 1 for CYP2C19*2 AA, θrs12769205 = 0.887 for CYP2C19*2 GA, and θrs12769205 = 0.744 for CYP2C19*2 GG.

The typical CL/F (1.7 L/h/kg) and Vd/F (26.4 L) were consistent with literature values12,13,15.

Final PopPK parameters for Models I and II, including estimates and relative standard errors (RSEs), are summarized in Table 2.

Notably, the V-BW relationship was excluded from the final modeling due to unacceptable allometric scaling instability (RSE = 327.4%) compared to the robust base model (RSE < 15%). Furthermore, while MCHC demonstrated marginal influence on Vd/F during covariate screening, the ΔOFV of 6.9 failed to meet the formal statistical threshold (Δ10.83, p < 0.001).

Model evaluation

The diagnostic goodness-of-fit (GOF) plots of the base and finally proposed models are presented in Fig. S1. The conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) vs. population prediction (PRED) and time after the first dose showed a random distribution around 0, with the majority of them within an acceptable range (−2 to 2). No systematic bias is shown in the GOF plots.

The bootstrap analysis results are summarized in Table 2. The median bootstrap estimates aligned well with the final parameter estimates for Models I and II, with acceptable biases of <±3%, demonstrating the reliability and robustness of both models. In Model I, the η-shrinkage for inter-individual variability (IIV) in CL/F was 18.2%, with an equal ε-shrinkage of 14.1% observed for both residual error components (proportional and additive). In Model II incorporating genetic covariates, the η-shrinkage for IIV in CL/F increased to 22.6% (vs. 18.2% in Model I), while both residual error components showed reduced ε-shrinkage to 12.7% (vs. 14.1% previously). The proportional and additive error variances remained stable at 0.0301 and 0.307, respectively.

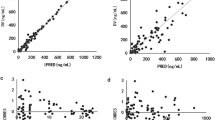

The visual predictive checks (VPC) is shown in Fig. S2. Most observed data points fell within the 90% prediction interval (PI) of 1000 simulations, demonstrating the final model’s precise predictive performance. Numerical predictive checks (NPC) analysis further supported this finding, with only 3.75% (Model I) and 4.32% (Model II) of observed concentrations outside the 95% PI (Table S6), respectively. Additionally, normalized prediction distribution errors (NPDEs) followed a standardized normal distribution, as confirmed by statistical tests and graphical analysis (Fig. 1).

Moreover, the results of the external validation are shown in Fig. S3. Both final Models I and II achieved F20 values exceeding 35% and F30 values exceeding 50%, indicating that the accuracy and precision of the model’s predictions meet the required standards.

Based on the above results, we concluded that the final Models I and II showed satisfactory predictive performance.

Simulation

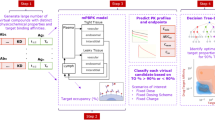

The validated Model I was used to simulate and determine the optimal maintenance dose range for populations without genotype data. By ensuring that the simulated concentration interquartile ranges fell within the target therapeutic range of 2–7 μg/mL, maintenance dose ranges were established for both BW-adjusted (mg/kg) and BW-band dosing (mg) strategies (Fig. 2). For BW-adjusted dosing, cases weighing 10–15 kg were recommended 5–8 mg/kg per dose, while those weighing 15–20 kg, 20–40 kg, and 40–50 kg were advised 4–6 mg/kg, 3–4 mg/kg, and 2–3 mg/kg per dose, respectively. For BW-band dosing, the corresponding doses were 50–100 mg, 75–100 mg, 75–125 mg, and 100–150 mg per dose, respectively (Regimen A, Fig. 3 and Table S7).

Created in BioRender. Lee, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/pryerjz.

A simplified dosing strategy (Regimen B) was also simulated, recommending 3.5 mg/kg per dose for children weighing 10–50 kg and 100 mg per dose for those ≥50 kg under BW-adjusted dosing, respectively. For fixed dosing, a uniform dose of 100 mg per dose was recommended for all children weighing ≥10 kg. Simulations confirmed that these regimens achieved the target concentrations (Fig. S4).

For special cases, including patients aged 1–4 years and obese cases, dose optimization was further explored (Supplementary Figs. S5–S7). Significant differences in LCM exposure were observed between CYP2C19*2 rs12769205 wild-type (AA) and mutant (GG) genotypes using Model II. Dose adjustments were made to account for these differences, with detailed results shown in Figs. S8–S13.

Validation of the dosing regimens using the validation dataset demonstrated initial target concentration achievement rates of 61.2–88.7%. Rates were notably lower (<75%) for patients aged 1–4 years. After dose adjustment, target achievement rates improved significantly, exceeding 78% across most subgroups (Fig. 4). Notably, Regimen B (fixed dose of 3.5 mg/kg) resulted in suboptimal exposure for lower-BW cases, with a target achievement rate of only 71.4%.

The heatmap illustrates the target concentration (2–7 μg/mL) attainment rates across different scenarios. The color gradient, ranging from purple (high attainment) to pink (low attainment), demonstrates the performance of each regimen in population subgroups stratified into discrete BW ranges. a–c Dosing adjustments based on BW alone; d–f Dosing adjustments based on both BW and CYP2C19*2 genotype data. Created in GraphPad Prism 10.

For genotype-informed regimens (C, D, and G), initial target achievement rates ranged from 61.2% to 92.0%, with wild-type patients generally achieving rates below 75%. After dose adjustment, the rates were improved obviously (Fig. 4). Regimen H, which included adjustments for specific genotype-weight subgroups (e.g., AA genotype in 10–15 kg and GG genotype in 40–50 kg), could not be further validated due to the absence of these subgroups in the validation set.

Discussion

Given the practical challenges associated with the current mg/kg dosing approach for LCM in pediatric epilepsy management, we sought to test the feasibility of transitioning to fixed-dose regimens or BW-band (mg) dosing through a PopPK modeling strategy. The theoretical hypothesis lies in a pharmacokinetic comparability: assuming comparable clinical outcomes when plasma LCM concentrations are maintained within a defined therapeutic range (e.g., 2–7 μg/mL10), the rationale for interchangeable dosing regimens can be assessed by comparing target concentration attainment rates across different dosing approaches. This study represents the first reported efforts to implement such a strategy in this field. In the following sections, we will discuss our key findings and innovations, which challenge conventional mg/kg-normalized dosing paradigms and provide PopPK-based evidence for optimizing pediatric ASMs.

The development of PopPK models matched to the clinical scenarios of LCM was the first step in this study. Through PopPK analysis, BW and CYP2C19*2 genotype were identified as the two primary covariates significantly influencing LCM’s CL/F. Considering two real-world clinical scenarios based on the availability of CYP2C19*2 data, we conducted a comprehensive model evaluation of the two corresponding PopPK models: the BW-only model (Model I) and the model incorporating both BW and CYP2C19*2 mutation status (Model II).

Model I estimated the CL/F of 1.51 L/h, showing 18% interindividual variability, which was in line with pediatric reference values16. A significant positive correlation between BW and CL/F was observed, indicating that higher BW necessitates increased LCM doses1. This correlation likely reflected age-related maturation of renal function, as increased BW was associated with higher glomerular filtration rates17. Furthermore, LCM’s distribution in extracellular fluid suggested that total body water influenced plasma trough concentrations, potentially explaining why pediatric patients with larger BW exhibited relatively lower drug levels18,19.

Model II revealed that CYP2C19*2 significantly determined LCM's metabolism: homozygous carriers exhibited a 26.4% reduction in CL/F (i.e., 0.736 × wild-type; p < 0.001), consistent with the functional role of rs12769205 in CYP2C19*2 (PharmGKB; https://www.pharmgkb.org/). Indeed, CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms have been demonstrated to significantly influence exposure to LCM in several studies8,9,10,20. In this study, we also systematically evaluated the potential contributions of CYP2C9, ABCB1, and ABCC2 involving transport/metabolic pathways into LCM’s exposure. Notably, no significant influence was observed in this research and our previous study10, while other studies observed concentration fluctuations caused by ABCB1 and ABCC2 genetic polymorphisms21,22.

Impressively, the high prevalence of CYP2C19*2 in Asians (>30% allele frequency) will amplify its significance23,24,25, as reduced function may predispose these patients to supratherapeutic exposures. While comprehensive metabolic phenotyping could theoretically offer deeper mechanistic insights, practical considerations prioritized clinical utility. Specifically, our PopPK model identified CYP2C19 rs12769205 as the single actionable biomarker, thereby streamlining implementation without sacrificing predictive performance. This strategic prioritization of a key SNP over broader phenotyping facilitates the feasible integration of genotype-guided dosing into routine practice26,27. However, such CYP2C19*2-based findings should be contextually adapted for populations with distinct pharmacogenetic profiles (e.g., Oceanian *2 vs. African/European *17 predominance), as our findings underscore the need for ethnicity-aware optimization of the precision dosing strategies.

Next, we utilized the validated PopPK models I and II to evaluate the feasibility of the dosing regimen transition. Simulations revealed that BW-band (mg) dosing achieved comparable exposure to BW-adjusted (mg/kg) dosing across subgroups, with both dosing strategies attaining target concentrations (2–7 μg/mL), as shown in Fig. 2 and 3. For a representative 30 kg case (median BW in the study cohort), LCM administration could be implemented either as 3–4 mg/kg or 75–125 mg per dose, with both regimens demonstrating equivalent exposure profiles. Notably, a more simplified 100 mg fixed-dose regimen also maintained the therapeutic concentration while enhancing operational efficiency for patients ≥10 kg. If the above patient carried homozygous CYP2C19*2, a dose reduction was required from the baseline 3–4 mg/kg (75–125 mg) to 3 mg/kg (75–100 mg). This finding suggested that an mg dosing strategy may be a viable alternative, thereby simplifying the administration and expanding therapeutic options for pediatric patients.

Subsequently, we also employed the developed PopPK models I and II to assess the feasibility of dosing regimen transition in special populations. We have particularly focused on young children with epilepsy aged ≥1 and <4 years in this study. Currently, LCM has not been approved in China for the treatment of epilepsy in children aged 1–4 years. Due to limited data, this study relied on previously published PopPK models, which suggested that children aged 1–3 years required 13–14 mg/kg/day, while those over 3 years needed 12 mg/kg/day to achieve exposure levels comparable to older children12. In this study, we recommended dosing based on BW bands, which can bring similar LCM exposure in 1–4 years close to that of children over 4 years. Of note, the maximum dose for cases weighing 10–15 kg (16 mg/kg) was slightly higher than in previous studies12. In addition, administering the same doses (5 mg/kg or 100 mg per dose) also achieved the therapeutic exposure levels in this age group.

We have also specifically focused on those children with epilepsy who were overweight or obese. Overall, dosing regimens were largely consistent between obese and non-obese children. However, the primary differences emerged in two subgroups: younger obese cases with homozygous CYP2C19*2 mutations (BW < 15 kg) and older obese one with wild-type CYP2C19*2 (BW ≥ 50 kg), both necessitating an obvious dose reduction.

One more critical point warrants in-depth discussion. Upon acquisition of model-required covariate data, PopPK modeling enables precise simulation of individualized dosing regimens based on target therapeutic concentration ranges. This applies to both the current mg/kg-based dosing approach and the fixed-dose regimen (mg) under investigation in this study, where comprehensive PopPK simulations can identify “optimized” doses aligned with the target exposure thresholds.

The conventional titration-guided approach initiates therapy with label-recommended starting doses, requiring multiple empirical adjustments to reach therapeutic targets. This time-consuming trial-and-error process stems from inherent uncertainty in target dose localization. In contrast, PopPK-driven dose prediction provides mathematically derived optimal regimens, raising a pivotal question: should clinicians adhere to traditional stepwise titration or adopt model-informed precision dosing? This dilemma mirrors choosing between escalator (gradual titration) and elevator (direct target dosing) for reaching the same destination floor.

For LCM, with a favorable safety profile10, the PopPK-guided “elevator” dose tailoring may represent a scientifically justified strategy, potentially shortening the time to achieve therapeutic efficacy while maintaining tolerability. While adult prescribing guidelines incorporate validated loading dose regimens to achieve rapid seizure control and clinical stabilization, pediatric-specific data remain conspicuously absent in current literature11,12,15. However, a loading dose may be administered in pediatric patients for whom achieving the recommended maintenance dosage in a shorter timeframe is clinically indicated. Indeed, though LCM’s favorable tolerability and low incidence of adverse events, further research is warranted. Intriguingly, brivaracetam prescribing information states that no titration is required when initiating treatment, which perfectly aligns with our proposed “elevator approach” of rapidly achieving the maintenance dose.

This study has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this represented the largest PopPK study conducted to date using real-world clinical data from Chinese children with epilepsy (190 patients, 493 plasma drug concentration measurements). The research not only identified significant covariates affecting the CL/F of LCM but also established corresponding PopPK models based on potential clinical scenarios. These models could serve dual purposes: predicting achievable concentration ranges under specific dosages and simulating required dosing regimens based on target plasma drug concentrations. While the primary aim of this study was to explore the feasibility of transitioning LCM dosing strategies (from BW-adjusted mg/kg to fixed mg dosing) using the validated models, it concurrently raised a critical question for discussion: the implementation of model-predicted individualized dosing regimens presents a practical challenge analogous to choosing between escalators and elevators when ascending buildings—both achieve vertical mobility but differ fundamentally in implementation complexity and precision.

Due to the retrospective nature of our study, several limitations existed. Firstly, primarily restricted to trough concentration sampling, this methodology limited precise estimation of absorption rate constant (ka) and Vd with their IIVs. Although BW’s effects on Vd/F are well-documented, the allometric model (RSE = 327.4%) failed to detect this association due to parameter instability compared to the stable base model. Secondly, previous studies have highlighted the impact of concomitant drug use on LCM’s exposure1,3,12,28. However, we were unable to evaluate the potential effects of DDIs since our study population predominantly received monotherapy or rarely used enzyme-inducing antiseizure drugs and SCBs in combination. Thus, clinical application of this modeling to children with epilepsy on concomitant ASMs (specifically for SCBs or enzyme inducers) should be undertaken cautiously, and future studies with larger cohorts receiving polytherapy are warranted to fully characterize these potential interactions. Thirdly, due to the lack of clinical data on the use of LCM in infants aged between 1 month and 1 year, we were unable to conduct model simulations, and the results obtained couldn’t be extrapolated to this specific population. Finally, this modeling was unable to correlate directly with clinical endpoints such as seizure control or adverse effects. Future studies integrating pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling and/or machine learning may help bridge this gap. Despite these limitations, the study still provided valuable clinical insights, and the PopPK-guided dosing regimen proposed by the model may enhance the implementation of personalized dosing strategies.

In summary, this study identified BW and CYP2C19*2 genotype via PopPK modeling as the key determinants of exposure to LCM in children with epilepsy. The Models I and II enabled precise dose optimization according to different clinical scenarios. Of note, simulations revealed that fixed-dose or BW-band regimens (e.g., 100 mg for ≥10 kg) achieved therapeutic exposure comparable to the mg/kg approaches, simplifying the medication without compromising potential concentration that could achieved. Moreover, younger patients (1–4 years) and obese cases also benefited from the BW-based or genotype-informed dosing approaches. The above results in our study emphasized the critical role of PopPK-guided personalized dosing strategies. Future multicenter studies are warranted to validate these findings and further to refine the LCM therapy for pediatric epilepsy.

Methods

Study population

This study included children with epilepsy who underwent LCM treatment at the Department of Neurology, Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, between June 2021 and March 2023. Participants were randomly allocated into two groups: 70% were assigned to the model development group, and the remaining 30% were designated as the validation group.

Eligibility criteria required patients to meet the following conditions: (1) a confirmed diagnosis of epilepsy based on the criteria established by the ILAE committee29; (2) treatment with LCM under a consistent dosing regimen for at least 3 days to ensure steady-state plasma concentrations; (3) availability of complete medical records, including prescribed and administered medications, physiological and biochemical indicators, and blood collection times; and (4) at least two pre-dose (trough) plasma LCM concentration measurements. Cases with underlying metabolic or systemic disorders, as well as those with poor treatment compliance, were excluded from the study.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Protocol number 202409009-1). The study protocol complied with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, written informed consent was waived.

Study design and data collection

Clinical data, including demographic information (age, sex, and BW), treatment details (LCM dosing regimens, plasma concentrations, sample collection times, and concomitant medications), and laboratory findings (physiological and biochemical indicators), were retrospectively collected from the electronic medical records within the hospital information systems (HIS).

Pediatricians determined the initial dosage regimen based on the medication’s package insert and a thorough assessment of each patient’s clinical condition. LCM was administered orally in tablet form, with twice-daily dosing. Subsequent dose adjustments were tailored to individual cases by evaluating seizure frequency and comparing measured LCM concentrations against the target concentration range of 2–7 μg/mL, as evaluated in our prior research10.

Sample collection and concentration measurement

Steady-state plasma concentrations were achieved after each dose adaptation within 2–3 days. Peripheral venous blood (1–2 mL) was collected 30 min before the next maintenance dose.

The trough concentration of LCM was measured via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry methodology, a previously published method by our team30.

Of note, the precision and accuracy of plasma LCM concentration measurements, evaluated using three-level quality control samples, demonstrated inter-batch precision (RSD, %) and accuracy (RE, %) values of ≤± 6.7%, well within the predefined acceptance criteria of ≤± 15% (Table S2).

Genotyping

The genetic polymorphisms selected for analysis were based on prior research and data obtained from the PharmGKB database (https://www.pharmgkb.org). Ultimately, we identified and genotyped 9 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across 4 genes implicated in LCM disposition: ABCB1 (rs1045642, rs2032582, and rs3789243), ABCC2 (rs3740066 and rs717620), CYP2C9 (rs1057910), and CYP2C19 (*2, rs12769205; *3, rs4986893; and *17, rs3758581).

DNA was extracted from patients’ venous blood (which had been previously stored at −80 °C) by using a blood DNA kit (Zhongkebio Medical Technology, Nanjing, China). The selected nine SNPs in four human genes were genotyped using the Agena MassARRAY platform 4.0 with iPLEX gold chemistry (Agena Bioscience, Inc., CA, United States).

The design of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays and extension primers for these SNPs was performed using MassARRAY design software (v.4.0). The primers used are listed in Table S3. PCR master mixtures were obtained using the Agena PCR reagent set, the PCR procedures were started, and then the mixtures were treated with shrimp alkaline phosphatase. The masses of the primer extension products, corresponding to specific genotypes, were determined through matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (Agena Bioscience, Inc., CA, United States). Final genotypes were ascertained using MassARRAY TYPER 4.0 software (Agena Bioscience, Inc., CA, United States).

The allele and genotype frequencies of the selected genes were assessed for deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium using a goodness-of-fit chi-square test.

PopPK modeling

PopPK modeling was conducted by a nonlinear mixed effect modeling (NONMEM) approach using NONMEM® (v.7.3.0) with a Fortran compiler aided by Perlspeaks-NONMEM® (PsN, v.4.9.0). The R package (v.4.3.0) was used to analyze and graphically represent the NONMEM outputs. Pirana software (v.2.9.7) was used as a graphical user interface. Modeling details such as formulas and the NONMEM code are provided in Supplementary Material S.4.

Base model

Current evidence suggests that the pharmacokinetics of LCM can be adequately described using a one-compartment model15. Consequently, a one-compartment model with first-order absorption and elimination (implemented via the ADVAN2 TRANS2 subroutine) was employed to analyze the concentration-time data. Pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated using the first-order conditional estimation method with eta-epsilon interaction (FOCE-I) during the model-building process. However, due to limited sampling data during the absorption phase, the ka could not be reliably estimated. Therefore, ka was fixed at 2.45 h−1, based on values reported in a previous study15. Furthermore, as bioavailability (F) could not be determined, CL and Vd were expressed as apparent values (CL/F and Vd/F, respectively).

Maturation model

The influence of body size and maturation on drug disposition in pediatric patients is widely acknowledged31,32. In this study, the two most common models integrating BW were assessed to forecast drug clearance in children.

Covariate model

Prior to covariate screening, an exploratory analysis assessed covariate distribution and correlations. The PopPK model incorporated demographics (i.e., age, sex, and BW), ASMs, genetic variants (i.e., CYP2C19, CYP2C9, ABCB1, and ABCC2), complete blood count, and biochemical tests (i.e., liver/kidney function, lipids, and electrolytes) to optimize LCM dosing.

Continuous covariates were tested using linear or non-linear (power/exponential) relationships, while categorical covariates were evaluated via additive/proportional models. A stepwise approach identified significant covariates: forward inclusion required ΔOFV > 3.84 (P < 0.05, df = 1), and backward elimination retained covariates if ΔOFV > 10.83 (P < 0.001, df = 1).

Model selection prioritized lower AIC and Bayesian information criterion values33, alongside physiological plausibility and parameter accuracy, iterating until OFV stabilized.

Model evaluation

Model stability and predictive performance were evaluated using standard internal and external validation methods. GOF plots compared the base and final models with observed LCM concentration-time data. A bootstrap procedure (1000 resamples) provided medians and 5th–95th percentiles of model parameters. Predictive performance was assessed using VPC and NPC based on 1000 simulated datasets. VPC analysis plotted the 2.5th, 50th, and 97.5th percentiles of observed data against the 95% confidence interval (CI) of simulated concentrations. NPDE method (1000 datasets) further evaluated model diagnostics.

External validation used a separate validation dataset, with prediction bias being assessed via prediction error (PE%), mean prediction error (MPE%), mean absolute prediction error (MAPE%), and proportions of PE% within ± 20% (F20) and ± 30% (F30)34. Formulas are provided in Supplementary Material S.5.

Simulation of dosing regimen

The dosing regimen was designed using a model-informed approach, with Monte Carlo simulations being employed to account for variability across different clinical scenarios. To address genotype data accessibility in real-world practice, we tried to develop two models: Model I (only BW included) and Model II (CYP2C19 genotype-integrated further). Both models were subjected to rigorous evaluation criteria before simulations were conducted.

The optimization protocol targeted pediatric epilepsy management through covariate-driven adjustments, comparing BW-adjusted (mg/kg) and BW-band (mg) dosing while accounting for critical covariates: age, BW, and pharmacogenetic variants. Based on established therapeutic thresholds, LCM’s effective concentration range was defined as 2–7 μg/mL10. Simulations incrementally evaluated dose levels spanning 2–8 mg/kg and 50–200 mg fixed doses across covariate-stratified virtual cohorts. Box plots were generated to identify doses corresponding to the target concentrations of 2–7 μg/mL for each subgroup.

Special population, including pediatric patients aged 1–4 years and obese cases, was a key focus of this study. Obese patients were defined by obesity diagnoses documented in the HIS medical records, supplemented using WHO criteria and Child Growth Standards (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight).

Monte Carlo simulations were performed to derive optimal maintenance dose ranges for these groups, accounting for potential pharmacokinetic differences.

In cases where the final model included CYP2C19 genotype data (Model II), patients were further stratified by genotyping. Simulations were conducted using recommended doses derived from the non-genotyping model, and box plots were used to assess concentration fluctuations across the genotyping subgroups. This allowed for the derivation of adjusted maintenance doses tailored for both genotype-informed and non-genotype-informed scenarios.

To validate the simulated dosing regimens, the original validation dataset was subjected to 1000 simulations to evaluate the target concentration attainment rate. The dataset was then modified according to the simulated recommended doses, and simulations were repeated to assess changes in attainment rates following dose adjustment. This step ensured the robustness and clinical applicability of the proposed dosing regimens.

Data availability

The original data that support the findings of this study can be made available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request, without undue reservation.

Code availability

Modified R plotting scripts (derived from open-source code) and NONMEM files are available upon request (contact corresponding author; R ≥ v.4.3.0 required).

References

Li, Y. et al. Plasma lacosamide monitoring in children with epilepsy: focus on reference therapeutic range and influencing factors. Front. Pediatr. 10, 949783 (2022).

Cawello, W., Fuhr, U., Hering, U., Maatouk, H. & Halabi, A. Impact of impaired renal function on the pharmacokinetics of the antiepileptic drug lacosamide. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 52, 897–906 (2013).

May, T. W., Helmer, R., Bien, C. G. & Brandt, C. Influence of dose and antiepileptic comedication on lacosamide serum concentrations in patients with epilepsy of different ages. Ther. Drug Monit. 40, 620–627 (2018).

Rosati, A. et al. Long-term efficacy of add-on lacosamide treatment in children and adolescents with refractory epilepsies: a single-center observational study. Epilepsia 59, 1004–1010 (2018).

Bauer, S. et al. The efficacy of lacosamide as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy in focal epilepsy and its use in status epilepticus: clinical trial evidence and experience. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 10, 103–126 (2017).

Auvin, S. et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of adjunctive lacosamide in pediatric patients with epilepsy syndromes associated with generalized seizures: phase 2, open-label exploratory trial. Epilepsia 64, 2947–2957 (2023).

Schultz, L. & Mahmoud, S. Is therapeutic drug monitoring of lacosamide needed in patients with seizures and epilepsy?. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 45, 315–349 (2020).

Ahn, S. J. et al. Effects of CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics of lacosamide in Korean patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia 63, 2958–2969 (2022).

Zhao, T. et al. Effects of CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 polymorphisms on the efficacy and plasma concentration of lacosamide in pediatric patients with epilepsy in China. Eur. J. Pediatr. 184, 73 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. CYP2C19 genotype and sodium channel blockers in lacosamide-treated children with epilepsy: two major determinants of trough lacosamide concentration or clinical response. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 17, 17562864241273087 (2024).

Winkler, J., Schoemaker, R. & Stockis, A. Modeling and simulation for the evaluation of dose adaptation rules of intravenous lacosamide in children. Epilepsy Res 149, 13–16 (2019).

Lukka, P. B. et al. Use of real-world data and pharmacometric modeling in support of lacosamide dosing in pediatric patients under 4 years of age. J. Clin. Pharm. 61, 881–888 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. How to handle a missed or delayed dose of lacosamide in pediatric patients with epilepsy? a mode-informed individual dosing. Epilepsy Behav. 151, 109601 (2024).

Zhu, X., Guo, L., Zhang, L. & Xu, Y. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling of lacosamide in patients with hepatic and renal impairment and pediatric populations to support pediatric dosing optimization. Clin. Ther. 46, 258–266 (2024).

Winkler, J., Schoemaker, R. & Stockis, A. Population pharmacokinetics of adjunctive lacosamide in pediatric patients with epilepsy. J. Clin. Pharm. 59, 541–547 (2019).

Hoy, S. M. Lacosamide: a review in focal-onset seizures in patients with epilepsy. CNS Drugs 32, 473–484 (2018).

Batchelor, H. K. & Marriott, J. F. Paediatric pharmacokinetics: key considerations. Br. J. Clin. Pharm. 79, 395–404 (2015).

May, T. W., Brandt, C., Helmer, R., Bien, C. G. & Cawello, W. Comparison of lacosamide concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid and serum in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia 56, 1134–1140 (2015).

Carona, A. et al. Pharmacology of lacosamide: from its molecular mechanisms and pharmacokinetics to future therapeutic applications. Life Sci. 275, 119342 (2021).

Barry, J. M. et al. Prediction of lacosamide concentrations to support dose optimization during pregnancy. Epilepsia 66, 346–355 (2025).

Zhao, T. et al. Impact of ABCB1 polymorphisms on lacosamide serum concentrations in Uyghur pediatric patients with epilepsy in China. Ther. Drug Monit. 44, 455–464 (2022).

Zhao, T. et al. Impact of ABCC2 1249G>A and -24C>T polymorphisms on lacosamide efficacy and plasma concentrations in Uygur pediatric patients with epilepsy in China. Ther. Drug Monit. 45, 117–125 (2023).

Shi, Y. et al. Differences in the proportion of CYP2C19 loss-of-function between cerebral infarction and coronary artery disease patients. Int. J. Gen. Med. 16, 3473–3481 (2023).

Yuan, X. W., Yuan, S. Y., Wu, G. X., Wu, Z. X. & Guan, Z. Y. Genetic polymorphism of clopidogrel metabolism related gene CYP2C19 gene in Chinese from Foshan area of Guangdong Province. Hematology 27, 1056–1061 (2022).

Biswas, M., Jinda, P. & Sukasem, C. Pharmacogenomics in Asians: differences and similarities with other human populations. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 19, 27–41 (2023).

Brouwer, J. et al. Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG) guideline for the gene-drug interaction between CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 and SSRIs. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 30, 1114–1120 (2022).

Wu, W. W. et al. A national-wide survey on clinical implementation of PGx testing into precision therapeutics for Chinese children: a long way before standard clinical practice. BMC Health Serv. Res. 24, 1089 (2024).

Contin, M. et al. Lacosamide therapeutic monitoring in patients with epilepsy: effect of concomitant antiepileptic drugs. Ther. Drug Monit. 35, 849–852 (2013).

Scheffer, I. E. et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: position paper of the ILAE commission for classification and terminology. Epilepsia 58, 512–521 (2017).

Zhang, Y. Y. et al. An LC-ESI-MS/MS assay for the therapeutic drug monitoring of 15 antiseizure medications in plasma of children with epilepsy. Biomed. Chromatogr. 36, e5484 (2022).

Liu, T., Ghafoori, P. & Gobburu, J. V. Allometry is a reasonable choice in pediatric drug development. J. Clin. Pharm. 57, 469–475 (2017).

Li, D. Y. et al. Population pharmacokinetics modeling of vancomycin among chinese infants with normal and augmented renal function. Front. Pediatr. 9, 713588 (2021).

Byon, W. et al. Establishing best practices and guidance in population modeling: an experience with an internal population pharmacokinetic analysis guidance. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharm. 2, e51 (2013).

Dai, H. R. et al. Population pharmacokinetic modeling of caffeine in preterm infants with apnea of prematurity: new findings from concomitant erythromycin and AHR genetic polymorphisms. Pharm. Res. 184, 106416 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Specially Appointed Medical Expert Project of the Jiangsu Commission of Health (2019), China International Medical Foundation-Chinese Society of Clinical Pharmacy Fund (Z-2021-46-2101), Jiangsu Research Hospital Association for Precision Medication (JY202108), the Hospital Pharmacy Foundation of Jiangsu Pharmaceutical Association (A202217), the CAAE Epilepsy Research Fund of China Association Against Epilepsy (CU-2022-024 and CU-2024-009), and by the General Clinical Research Projects of Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (LCYJY202322).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Z., X.-P.L., F.C.: Conceptualization. L.F., J.W., Y.-Y.Z., Y.-H.H., J.-C.Q.: Methodology and investigation. L.F., C.-F.W., J.C.: Resources and data curation. Y.L., H.-L.G.: Software, validation, and formal analysis. Y.L., F.C.: Writing – original draft. H.-L.G., G.Z., X.-P.L., F.C.: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. H.-L.G., J.-C.Q., C.-F.W., X.-P.L., F.C.: Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Guo, HL., Fan, L. et al. PopPK modeling supports BW band dosing of lacosamide for pediatric epilepsy. npj Genom. Med. 10, 61 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-025-00519-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-025-00519-y