Abstract

Eyes shut homolog (EYS) is the most common autosomal recessive causative gene of inherited retinal dystrophy (IRD) in the Japanese population, yet genotype–phenotype correlation data remain limited. We analyzed 291 probands (141 males, 150 females) with IRD caused by EYS (EYS–RD) from eight Japanese facilities. Clinical variables included age at onset, initial symptoms, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), and its progression alongside genotype information. Mean onset was 25.8 ± 14.9 years, most often night blindness (67.0%), and rod–cone dystrophy was observed in 95.9%. Initial BCVA averaged 0.34 ± 0.56 logMAR, declining 0.03 ± 0.06 logMAR/year, with low vision and blindness estimated at 48.4 and 73.6 years, respectively. Three major East Asian–specific pathogenic variants (S1653fs, Y2935X, and G843E) accounted for 88.7% of all cases. S1653fs homozygotes showed the earliest onset (mean, 18.4 years). These findings support the potential of genetic testing for personalized medicine tailored to population characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP) is the most common form of hereditary retinal degenerative disease, affecting approximately 1 in 3000–4000 people, with an estimated 2.5 million people affected worldwide1,2,3,4. This disorder is characterized by the progressive degeneration from rod to cone cells, eventually leading to blindness1,2,3,4. In Japan, RP is the second leading cause of blindness1,2,3. RP is the most common type of Inherited retinal dystrophy (IRD) and belongs to a group of Mendelian disorders, typically inherited in an autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive (AR), or X-linked patterns1,2,3,4.

In ophthalmology, estimating the time until a patient progresses to visual impairment or blindness is a common concern. However, current clinical guidance on this matter remains limited, particularly regarding IRD. This is primarily due to the genetic diversity of IRD, which involves >300 causative genes (RP: >90 genes)5. Although several studies have identified the clinical differences associated with specific causative genes6,7, the genetic background of IRD remained heterogeneous in many clinical studies, including our previous studies8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. While it is important to understand the natural history of a population with a homogeneous genetic background, the involvement of specific causative genes in the clinical characteristics of RP has been limited to evaluation in only a small number of patients. This needs to be validated in a large sample size.

Among the causative genes in RP, eyes shut homolog (EYS) has been identified in several representative genetic analysis studies21,22,23,24,25 and is the most common AR causative gene associated with IRD in the Japanese population26,27,28,29. EYS is the largest gene related to the eye; it was initially reported as the causative gene of ARRP in 200830. It spans approximately 2 Mb of chr6q12 and comprises 44 exons encoding the protein of 3146 amino acids, which is predominantly expressed in the retina31. The gene contains 27 epidermal growth factor-like domains and five laminin G-like domains that are highly conserved across species30. Although EYS may play an essential role in photoreceptor morphogenesis30, its functional and structural properties remain incompletely characterized25. Additionally, its large size has prevented the development of knockout models, resulting in insufficient evaluation of genotype-phenotype correlations. Therefore, studies involving human participants are crucial for a comprehensive phenotypic analysis of IRD caused by EYS (EYS–RD).

This multicenter study aimed to investigate the clinical characteristics of EYS–RD, which is currently the most common causative gene in the Japanese population. Using data from the Japan Retinitis Pigmentosa Registry Project at eight Japanese facilities, we included a large number of RP patients with a homogeneous genetic background, 141 men and 150 women with EYS–RD, with the aim of evaluating the natural history of EYS–RD and establishing standard clinical data for Japanese patients with IRD.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the 291 patients with EYS–RD are presented in Table 1. The mean age at the initial visit was 45.6 ± 14.9 years, the mean duration of observation was 7.7 ± 6.3 years, and the mean age at disease onset was 25.8 ± 14.9 years. The initial symptoms of EYS–RD included night blindness (67.0%), visual field impairment (8.2%), and loss of visual acuity (VA) (6.5%). Family history and consanguineous marriages were present in 28.5% and 9.3% of the patients, respectively. Rod-cone dystrophy and cone-rod dystrophy accounted for 95.9% and 2.4% of patients, respectively. Approximately 11.3%, 3.8%, and 0.3% of the patients had a history of epiretinal membrane, macular edema, and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in the right eye, respectively.

Pathogenic variants causing EYS–RD in Japan

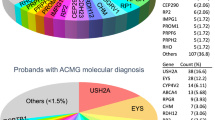

A schematic representation of the EYS protein domains and the distribution of pathogenic variants is shown in Fig. 1A. The classifications of different pathogenic variants detected in EYS–RD are presented in Fig. 1B. In total, 39.7% of the detected variants were missense, 39.7% were frameshift, 18.7% were nonsense, 0.34% were large deletions, 0.17% were duplications, and 1.37% were splice-site variants in this study population.

A Schematic representation of the EYS protein structure, highlighting domain organization and the location of representative pathogenic variants identified in Japanese patients with EYS-associated retinal dystrophy. The protein includes epidermal growth factor (EGF) domains, EGF-like domains, calcium-binding EGF-like (EGF-CA) domains, low complexity regions, and multiple laminin G (LamG) domains in the C-terminal region. Variant positions are indicated above the schematic, with frameshift, nonsense, missense, and deletion variants annotated accordingly. This figure was created using Microsoft Office software. B Pie chart illustrating the classification of the types of pathogenic variants detected in the EYS gene. In total, 39.7% of the detected variants were missense, 39.7% were frameshift, 18.7% were nonsense, 0.34% were large deletions, 0.17% were duplications, and 1.37% were splice-site variants in this study population. This figure was created using Microsoft Office software.

Human lifespan and logMAR BCVA for EYS–RD at the initial and last visit

In 66.0% of all patients without cataract surgery, the mean logMAR BCVA at initial visit was 0.34 ± 0.56, and the mean progression was 0.03 ± 0.06 per year (Fig. 2). Approximately 50% of the patients had low vision (3/10), whereas 20% were blind (2/40). However, 25% of all patients aged ≥65 years maintained a VA of ≥0.3 (decimal BCVA [WHO category 0]). Among 137 EYS–RD patients with two logMAR BCVA data points without intraocular lenses, the estimated ages of low vision and blindness (WHO definitions) (95% confidence intervals) were 48.4 (45.8−51.0) and 73.6 (68.2−78.9) years, respectively.

This scatterplot illustrates the longitudinal changes in logMAR best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in patients with EYS-associated retinal dystrophy. White circles represent visual acuity measurements at initial visits, while black circles indicate measurements at the last follow-up visits, with paired data points connected by gray lines. The mean age at disease onset was 25.8 ± 14.9 years, while the mean age at initial clinical visit was 45.6 ± 14.9 years. The mean logMAR BCVA at initial visit was 0.34 ± 0.56, corresponding to a decimal visual acuity of 0.4–0.5. The background displays silhouettes representing different life stages, with the working-age period (15–65 years) marked along the horizontal axis. Horizontal dashed lines indicate visual impairment thresholds, with the WHO Category 2 to 3 boundary (logMAR 1.3) highlighted. This figure was created using RStudio, with background silhouettes designed by LAIMAN, Inc.

Multivariate analysis of factors affecting BCVA

The multivariate analysis of the factors affecting BCVA at the initial visit showed that age at the initial visit, age at onset, and the presence of consanguinity of parents affected VA (Table 2). The multivariate evaluation of the factors contributing to changes in corrected VA per year indicated that macular hole significantly influenced the progression of VA loss (Supplementary Table 1).

Variant-based analyses

The frequency of pathogenic AR variant combinations is shown in Fig. 3A. In patients with EYS–RD, 88.7% harbored the three major pathogenic variants (S1653fs, Y2935X, and G843E). The most common combination was S1653fs and G843E, followed by the homozygous S1653fs. Fig. 3B illustrates that these three major variants are specific to East Asian populations.

A The upper left panel displays individual allele counts of the pathogenic variants. The lower panel illustrates the frequency of variant combinations in patients, with connected dots in the left matrix indicating specific combinations of variants present in individual patients. The horizontal bars represent the number of patients (N) carrying each combination pattern, with the most frequent combination being the compound heterozygous combination of S1653fs and G843E, followed by the homozygous S1653fs. This figure was created using RStudio. B World distribution maps of the top three pathogenic variants (S1653fs, G843E, and Y2935X) with their corresponding allele frequencies in different population databases. For each variant, frequencies are shown from four genomic databases: gnomADv4 (global), gnomADv4 East Asian population (EAS), 14KJPN (Japanese population database), and KGP (Korean Genome Project). The maps highlight regions where these variants show higher prevalence, with darker shading in East Asia reflecting the increased frequency of these variants in Asian populations. This figure was created using Microsoft Office software.

Table 3 presents a comparison of the clinical characteristics of the homozygotes for the three major pathogenic variants (S1653fs, Y2935X, and G843E). The patients with homozygous S1653fs (N = 26) exhibited an earlier onset of EYS–RD compared with those with G843E (N = 22) and Y2935X (N = 13) (G843E vs. S1653fs: P = 0.014; Y2935X vs. S1653fs: P = 0.013), which were significant after Bonferroni correction (Fig. 4). The mean annual rates of VA progression were 0.05 ± 0.08, 0.02 ± 0.02, and 0.04 ± 0.05 in S1653fs, G843E, and Y2935X, respectively. Analysis using the linear mixed-effects model revealed that G843E and Y2935X had a non-significant difference in the effect on BCVA decline with a coefficient of −0.006 (95% CI: −0.024 to 0.013) (P = 0.54) and 0.006 (95% CI: −0.015 to 0.028) (P = 0.56), compared with the homozygote S1653fs, respectively. The estimated ages of blindness onset in homozygotes of S1653fs (n = 15), G843E (n = 11), and Y2935X (n = 9) were 73.8 (95% CI: 59.1−88.5), 90.4 (95% CI: 61.3−119.4), and 70.1 (95% CI: 52.2−88.0) years, respectively, although no statistical difference was observed among the groups (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

This box-and-whisker plot illustrates the comparison of age at disease onset (years) among patients homozygous for the three most frequent pathogenic variants in the EYS gene: S1653fs (N = 26), G843E (N = 22), and Y2935X (N = 13). Individual data points are overlaid on each box plot. The horizontal line within each box represents the median, the box boundaries indicate the interquartile range (25th to 75th percentiles), and the whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Statistical comparison of mean onset ages was performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (α = 0.05/3). Significant differences (p < 0.0167) between groups are shown, while non-significant comparisons are labeled as N.S. This figure was created using Microsoft Office software and RStudio.

Furthermore, we performed a comparative analysis of phenotypic features, including additional clinical parameters, among the three major variant groups (Supplementary Table 2). In this analysis, significant differences among the three groups were detected with respect to visual field defects and epiretinal membrane.

Discussion

This multicenter retrospective study described the clinical characteristics of IRD caused by EYS (EYS–RD), which is currently the most common causative gene in the Japanese population. Data from 291 patients with EYS–RD showed a mean progression rate of VA (logMAR BCVA)/year of 0.03 (equivalent to a decimal VA decrease from 1.0 to 0.9). This finding indicates that EYS–RD may represent a mild phenotype of cone dysfunction. We further identified three major genetic variants (S1653fs, Y2935X, and G843E) in approximately 90% of Japanese EYS–RD, all of which are specific to the East Asian population. Comparisons of the clinical characteristics of the homozygotes of these three variants demonstrated that S1653fs was significantly associated with earlier onset, and that truncating variants (S1653fs and Y2935X) tended to show an earlier estimated age of blindness and the hypomorphic G843E a later age, though these latter differences were not significant.

A notable strength of this study is its scale, as it represents the largest EYS–RD clinical study. Given the retrospective design of this study and the rarity of the disease, we included all available and eligible cases from eight participating Japanese facilities to maximize statistical power and patient numbers. Although the registry does not include the general healthy population, the underlying source population can be estimated at approximately 15 million based on disease prevalence. This estimate illustrates the rarity of the condition and emphasizes the importance of registry-based studies in rare diseases.

Importantly, the majority of patients (96%) with EYS–RD showed rod-cone dystrophy, confirming the role of EYS as a causative gene of RP. These findings align with the reports of previous studies on European (Portuguese) patients with EYS–RD (N = 58), which observed similar ages of onset and disease-type rates32. The mean annual ΔlogMAR BCVA of 0.03 is consistent with the European cohort’s reported progression of 1.45–1.51 letters per year (0.028)32. Given that typical RP, which is primarily a rod-cone dystrophy, progresses by 2.3 letters (0.045) per year33, EYS–RD may represent a mild phenotype of cone dysfunction. In the present study, the decline in VA generally began after the age of 40 years. This decline may occur earlier than in the natural history of other IRDs (e.g., Bietti’s crystalline dystrophy34 or RP caused by S-antigen visual arrestin variants35). The pre-decline period in VA for EYS–RD may be an optimal window for gene therapy and neuroprotective treatments.

Although the clinical characteristics of EYS–RD are similar to those reported in the previous study in European patients32, notable differences in the genetic background exist among populations. Specifically, although EYS–RD follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, the present study revealed a low incidence of family history and consanguinity. Instead, high-frequency variants specific to East Asia were identified. These findings suggest that the three major pathogenic variants prevalent in the Japanese population may contribute to the sporadic occurrence of EYS–RD in a context of random mating, shaping the unique characteristics of Japanese EYS–RD.

Variations of clinical characteristics among three major pathogenic variants highlight the potential value of genetic testing in genetic counseling for patients with IRD, including life planning. Notably, patients with S1653fs-RD exhibited an earlier onset compared with those with the other two high-frequency pathogenic variants (Y2935X and G843E). This frameshift insertion variant, located in the middle of the protein structure, may contribute to the earlier onset of EYS–RD. In addition, patients with truncating variants (S1653fs and Y2935X) tended to have an earlier estimated age of blindness, whereas those with the hypomorphic G843E appeared to show a later estimated age of blindness. Although these observed differences did not reach statistical significance, the general trend aligns with the biological plausibility that hypomorphic variants, such as G843E, may retain partial protein function and consequently result in a milder phenotypic effect, whereas truncating variants confer a more deleterious impact. This observation is also consistent with the expected impact on the phenotype among the three variants based on their allele frequency in the general population (Fig. 3B)36.

This study had some limitations. First, the presence of missing values within the dataset due to interrupted outpatient visits and follow-ups, or failure to collect information despite contact. Specifically, the number of patients aged >70 years was limited, and therefore, the progress of this age group could not be adequately assessed. Second, we performed the largest EYS-RD study to date using data from the Japan Retinitis Pigmentosa Registry Project, but the sample size was still limited, particularly after stratification by homozygous variants, and this precludes definitive conclusions. In addition, although a Bonferroni correction was applied to pairwise comparisons among the three major variants, multiple clinical parameters were analyzed. Therefore, our findings, including statistical results based on P values, should be interpreted with caution. Larger prospective studies conducted in other institutions or East Asian populations (e.g., in China and Korea) are necessary to validate our findings. Third, the VA assessment relied on evaluations conducted at two time points, the initial and last visits, with the analysis assuming linearity in changes across all ages. Fourth, this study primarily focused on the changes in BCVA, reflecting cone dysfunction. Hence, the analysis of rod function, including visual field loss, is warranted. Fifth, the limited availability and variability of multimodal imaging and functional testing data, along with the lack of a standardized protocol across centers at the time of collection, made uniform analysis of these parameters difficult in the present study. To address this, several prospective, protocol-driven studies have been initiated within our study group, for example, the RP-PRIMARY study37, in which these data are being collected in a standardized manner for future evaluation. Sixth, regional sampling bias cannot be excluded, although cases were collected from a wide range of facilities across Japan. However, our previous study demonstrated that the major variants (S1653fs and Y2935X) observed in the Japanese population are distributed nationwide without significant regional differences38, thereby minimizing the potential impact of such bias on our findings. Seventh, differences in instrumentation, examination protocols, or examiner technique across centers may have introduced additional variability, despite the use of standardized procedures. Therefore, possible centre-to-centre measurement variability might have affected data consistency. Furthermore, patients with structural variants, such as copy number variations, large deletions, and Alu insertions, were underrepresented. Future studies should address the clinical phenotypes of Japanese EYS–RD caused by these variants39,40,41,42,43,44,45.

In conclusion, the present study described the clinical characteristics of Japanese patients with EYS–RD caused by pathogenic variants mainly specific to East Asia. The clinical differences among major East Asian-specific pathogenic variants of Japanese EYS–RD highlight the potential of genetic testing for personalized medicine tailored to population characteristics.

Methods

Study design and participants

The Japan Retinitis Pigmentosa Registry Project is a multicenter registry for patients with inherited retinal dystrophy, including RP, encompassing ~3000 registered patients. This multicenter retrospective study included 141 men and 150 women who were clinically and genetically diagnosed with EYS–RD registered at eight Japanese facilities, namely, Jikei University, Teikyo University, Hamamatsu University School of Medicine, Nagoya University, Kobe City Eye Hospital, Kyushu University, Miyata Eye Hospital, and University of Miyazaki from July 2018 to July 2023. From each family, only one proband with available data was consecutively recruited from the participating facilities in this registry. Exclusion criteria included incomplete genetic confirmation or inadequate clinical documentation.

Clinical Examination

We retrospectively collected patients’ clinical information from medical records. The clinical diagnosis of EYS–RD was made by trained ophthalmologists at each facility based on the history of night blindness, visual field constriction, and/or ring scotoma and the results of comprehensive ophthalmological examinations, including slit-lamp biomicroscopy, fundus photography, electroretinography, and optical coherence tomography. Genetic testing was performed on all patients, confirming biallelic pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in EYS as the causative gene.

The clinical characteristics [age at the initial visit, duration of observation, age of onset, initial symptoms, family history, history of consanguineous marriage, disease type, macular complications, history of cataract surgery, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution best-corrected visual acuity (logMAR BCVA), and its progression] of natural disease progression were evaluated. The mean ± standard deviation or proportion of each parameter was calculated. For patients homozygous for one of the three major pathogenic variants (S1653fs and Y2935X46,47,48, and G843E29,49), we evaluated the clinical findings of each variant.

BCVA was measured using the Landolt decimal VA chart at 5 m or with single Landolt test cards. The values were converted to the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) for statistical evaluation. The logMAR values for counted fingers, hand motion, light perception, and no light perception were 2.3, 2.6, 2.9, and 3.2, respectively50. The World Health Organization (WHO) definitions of low vision (3/10) and blindness (2/40) were used as the threshold values51. Some patient data have previously been published in a case report or case series46,48,52.

Detection of pathogenic variants in EYS

Peripheral blood samples and salivary specimens were collected from all patients, and genomic DNA was extracted. Genetic variants were detected by direct Sanger sequencing of the EYS gene, multiplex polymerase chain reaction-based target sequencing21 or whole-exome sequencing with a target analysis of retinal disease-associated genes22,23. All variants detected in EYS were classified according to the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics53. The included variants were annotated using ANNOVAR software (version 3.4)54 and SnpEff (version 4.3)55. The minor allele frequency was obtained from gnomAD v456, 14KJPN57, and the Korean Genome Project58.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of clinical data among the three groups were performed using Fisher’s exact test and the Kruskal–Wallis test. For pairwise comparisons, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was applied with Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple testing. Multivariable linear regression models were used to assess factors influencing best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) at the initial visit and the annual change in BCVA. The ages at which visual acuity declined to low vision (logMAR BCVA = 0.523) and blindness-equivalent (logMAR BCVA = 1.3) were estimated using a linear mixed-effects model for repeated measurements20,59,60,61. Only patients with two observations of logMAR BCVA and no intraocular lens implantation were included. We fitted linear mixed-effects models with a random intercept for each participant to account for within-subject correlation. Random slopes were not modeled because only two time points per participant were available, leading to poor identifiability. To compare among the three major variant groups, age (years, continuous), variant status, and their interaction were included as fixed effects. For each variant group, the age at which BCVA reached the clinical thresholds (logMAR 0.523 and 1.3) was estimated from the fitted model coefficients, and differences in threshold ages between groups were evaluated by comparing these estimates. For variables with missing data, we performed complete-case analyses, excluding observations with missing values for the variable under consideration. As an exception, in the multivariable analyses, the missing-indicator method was applied. All statistical tests were two-sided, and significance was set at p < 0.05, except where Bonferroni adjustment was applied. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 3.4.4).

Ethics Statements

This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the 2013 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Graduate School and Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto University (RADDAR-J [72]). The study was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to sample testing.

Data availability

Due to privacy and ethical restrictions, the data are not publicly accessible and are available only on request.

Code availability

All analyses in this study were conducted using publicly available code and software. No custom code was developed.

References

Hartong, D. T., Berson, E. L. & Dryja, T. P. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet 368, 1795–1809 (2006).

Murakami, Y. et al. Photoreceptor cell death and rescue in retinal detachment and degenerations. Prog. Retin Eye Res 37, 114–140 (2013).

Campochiaro, P. A. & Mir, T. A. The mechanism of cone cell death in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Prog. Retin Eye Res. 62, 24–37 (2018).

Dias, M. F. et al. Molecular genetics and emerging therapies for retinitis pigmentosa: Basic research and clinical perspectives. Prog. Retin Eye Res. 63, 107–131 (2018).

RetNet. https://retnet.org/; accessed August 23 (2024).

Koyanagi, Y. et al. Relationship between macular curvature and common causative genes of Retinitis Pigmentosa in Japanese patients. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 61, 6 (2020).

Nakamura, S. et al. Relationships between causative genes and epiretinal membrane formation in Japanese patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-024-06534-6 (2024).

Yoshida, N. et al. Clinical evidence of sustained chronic inflammatory reaction in retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology 120, 100–105 (2013).

Fujiwara, K. et al. Assessment of Central visual function in patients with Retinitis Pigmentosa. Sci. Rep. 8, 8070 (2018).

Koyanagi, Y. et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography of the macular microvasculature changes in retinitis pigmentosa. Acta Ophthalmol. 96, e59–e67 (2018).

Murakami, Y. et al. Relations among foveal blood flow, retinal-choroidal structure, and visual function in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59, 1134–1143 (2018).

Funatsu, J. et al. Direct comparison of retinal structure and function in retinitis pigmentosa by co-registering microperimetry and optical coherence tomography. PLoS One 14, e0226097 (2019).

Ishizu, M. et al. Relationships between serum antioxidant and oxidant statuses and visual function in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 60, 4462–4468 (2019).

Nakatake, S. et al. Early detection of cone photoreceptor cell loss in retinitis pigmentosa using adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 257, 1169–1181 (2019).

Fujiwara, K. et al. Aqueous flare and progression of visual field loss in patients with Retinitis Pigmentosa. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 61, 26 (2020).

Okita, A. et al. Changes of serum inflammatory molecules and their relationships with visual function in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 61, 30 (2020).

Nakamura, S. et al. Long-term outcomes of cataract surgery in patients with Retinitis Pigmentosa. Ophthalmol. Retin. 6, 268–272 (2022).

Okado, S. et al. Assessments of macular function by focal macular Electroretinography and static perimetry in eyes with Retinitis Pigmentosa. Retina 42, 2184–2193 (2022).

Shimokawa, S. et al. Recurrence rate of cystoid macular Edema with Topical Dorzolamide treatment and its risk factors in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Retina 42, 168–173 (2022).

Nishiguchi, K. M., Yokoyama, Y., Kunikata, H., Abe, T. & Nakazawa, T. Correlation between aqueous flare and residual visual field area in retinitis pigmentosa. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 103, 475–480 (2019).

Carrigan, M. et al. Panel-based population next-generation sequencing for inherited retinal degenerations. Sci. Rep. 6, 33248 (2016).

Ellingford, J. M. et al. Molecular findings from 537 individuals with inherited retinal disease. J. Med. Genet. 53, 761–767 (2016).

Carss, K. J. et al. Comprehensive rare variant analysis via whole-genome sequencing to determine the molecular pathology of inherited retinal disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100, 75–90 (2017).

Stone, E. M. et al. Clinically focused molecular investigation of 1000 consecutive families with inherited retinal disease. Ophthalmology 124, 1314–1331 (2017).

Marques, J. P. et al. Eyes shut homolog (EYS): Connecting molecule to disease. Prog. Retin Eye Res. 108, 101391 (2025).

Maeda, A. et al. Development of a molecular diagnostic test for Retinitis Pigmentosa in the Japanese population. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 62, 451–457 (2018).

Numa, S. et al. EYS is a major gene involved in retinitis pigmentosa in Japan: genetic landscapes revealed by stepwise genetic screening. Sci. Rep. 10, 20770 (2020).

Suga, A. et al. Genetic characterization of 1210 Japanese pedigrees with inherited retinal diseases by whole-exome sequencing. Hum. Mutat. 43, 2251–2264 (2022).

Goto, K. et al. Disease-specific variant interpretation highlighted the genetic findings in 2325 Japanese patients with retinitis pigmentosa and allied diseases. J. Med. Genet. 61, 613–620 (2024).

Abd El-Aziz, M. M. et al. EYS, encoding an ortholog of Drosophila spacemaker, is mutated in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Nat. Genet. 40, 1285–1287 (2008).

Collin, R. W. et al. Identification of a 2 Mb human ortholog of Drosophila eyes shut/spacemaker that is mutated in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 83, 594–603 (2008).

Soares, R. M. et al. Eyes shut Homolog-associated retinal degeneration: natural history, genetic landscape, and phenotypic spectrum. Ophthalmol. Retin. 7, 628–638 (2023).

Iftikhar, M. et al. Progression of retinitis pigmentosa on multimodal imaging: The PREP-1 study. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 47, 605–613 (2019).

Murakami, Y. et al. Genotype and long-term clinical course of Bietti crystalline dystrophy in Korean and Japanese patients. Ophthalmol. Retin. 5, 1269–1279 (2021).

Nishiguchi, K. M. et al. Phenotypic features of Oguchi disease and Retinitis Pigmentosa in patients with S-antigen mutations: a long-term follow-up study. Ophthalmology 126, 1557–1566 (2019).

Manolio, T. A. et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature 461, 747–753 (2009).

Murakami, Y. et al. Study protocol for a prospective natural history registry investigating the relationships between inflammatory markers and disease progression in retinitis pigmentosa: the RP-PRIMARY study. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 69, 378–386 (2025).

Koyanagi, Y. et al. Regional differences in genes and variants causing retinitis pigmentosa in Japan. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 65, 338–343 (2021).

Pieras, J. I. et al. Copy-number variations in EYS: a significant event in the appearance of arRP. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 5625–5631 (2011).

Eisenberger, T. et al. Increasing the yield in targeted next-generation sequencing by implicating CNV analysis, non-coding exons and the overall variant load: the example of retinal dystrophies. PLoS One 8, e78496 (2013).

Nishiguchi, K. M. et al. Whole genome sequencing in patients with retinitis pigmentosa reveals pathogenic DNA structural changes and NEK2 as a new disease gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 16139–16144 (2013).

Wormser, O. et al. Combined CNV, haplotyping and whole exome sequencing enable identification of two distinct novel EYS mutations causing RP in a single inbred tribe. Am. J. Med Genet. A 176, 2695–2703 (2018).

Sano, Y. et al. Likely pathogenic structural variants in genetically unsolved patients with retinitis pigmentosa revealed by long-read sequencing. J. Med. Genet. 59, 1133–1138 (2022).

Fernandez-Suarez, E. et al. Long-read sequencing improves the genetic diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa by identifying an Alu retrotransposon insertion in the EYS gene. Mob. DNA 15, 9 (2024).

Hiraoka, M. et al. Copy number variant detection using next-generation sequencing in EYS-associated retinitis pigmentosa. PLoS One 19, e0305812 (2024).

Hosono, K. et al. Two novel mutations in the EYS gene are possible major causes of autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa in the Japanese population. PLoS One 7, e31036 (2012).

Oishi, M. et al. Comprehensive molecular diagnosis of a large cohort of Japanese retinitis pigmentosa and Usher syndrome patients by next-generation sequencing. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55, 7369–7375 (2014).

Koyanagi, Y. et al. Genetic characteristics of retinitis pigmentosa in 1204 Japanese patients. J. Med. Genet. 56, 662–670 (2019).

Nishiguchi, K. M. et al. A hypomorphic variant in EYS detected by genome-wide association study contributes toward retinitis pigmentosa. Commun. Biol. 4, 140 (2021).

Scott, I. U. et al. Functional status and quality of life measurement among ophthalmic patients. Arch. Ophthalmol. 112, 329–335 (1994).

International Council of Ophthalmology (ICO). Visual acuity measurement standard. Kos, Greece: ICO (1984).

Suto, K. et al. Clinical phenotype in ten unrelated Japanese patients with mutations in the EYS gene. Ophthalmic Genet. 35, 25–34 (2014).

Richards, S. et al. ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 17, 405–424 (2015).

Wang, K., Li, M. & Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e164 (2010).

Cingolani, P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 6, 80–92 (2012).

Chen, S. et al. A genomic mutational constraint map using variation in 76,156 human genomes. Nature 625, 92–100 (2024).

Tadaka, S. et al. jMorp: Japanese Multi-Omics Reference Panel update report 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D622–D632 (2024).

Jeon, S. et al. Korean Genome Project: 1094 Korean personal genomes with clinical information. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz7835 (2020).

Fan, Q., Teo, Y. Y. & Saw, S. M. Application of advanced statistics in ophthalmology. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 6059–6065 (2011).

Jinapriya, D. et al. Anti-inflammatory therapy after selective laser trabeculoplasty: a randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Ophthalmology 121, 2356–2361 (2014).

Maguire, M. G. et al. Endpoints and design for clinical trials in USH2A-related retinal degeneration: results and recommendations from the RUSH2A Natural History Study. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 13, 15 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all the patients who participated in this study. We acknowledge the staff of the Laboratory for Genotyping Development in RIKEN and the RIKEN-IMS Genome Platform. This study was supported by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (grant numbers 20K23005, 22K16969, 23K27750 and 24K12771), Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development [the Practical Research Project for Rare/Intractable Disease (grant number: JP23ek0109632) and 24ek0109707h0001], Japanese Retinitis Pigmentosa Society (JRPS) Research Grant (YK), Takayanagi Retina Research Award (YK) and Medical Research Grant from the Nasu Foundation (YK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RESEARCH DESIGN: Yoshito Koyanagi, Koh-Hei Sonoda, Koji M. Nishiguchi, Yasuhiro Ikeda. DATA ACQUISITION AND/OR RESEARCH EXECUTION: Yoshito Koyanagi, Yusuke Murakami, Taro Kominami, Masatoshi Fukushima, Satoshi Yokota, Kei Mizobuchi, Go Mawatari, Kaoruko Torii, Yuji Inoue, Junya Ota, Daishi Okuda, Kohta Fujiwara, Hanayo Yamaga, Takahiro Hisai, Mikiko Endo, Tomoko Kaida, Kazunori Miyata, Shuji Nakazaki, Takaaki Hayashi, Yasuhiko Hirami, Masato Akiyama, Chikashi Terao, Yukihide Momozawa, and Yasuhiro Ikeda. DATA ANALYSIS AND/OR INTERPRETATION: Yoshito Koyanagi, Kensuke Goto, Hanae Iijima, Chikashi Terao, Yukihide Momozawa, Koji M. Nishiguchi, and Yasuhiro Ikeda. MANUSCRIPT PREPARATION: Yoshito Koyanagi, Yusuke Murakami, Taro Kominami, Masatoshi Fukushima, Kensuke Goto, Satoshi Yokota, Kei Mizobuchi, Go Mawatari, Kaoruko Torii, Yuji Inoue, Junya Ota, Daishi Okuda, Kohta Fujiwara, Hanayo Yamaga, Takahiro Hisai, Mikiko Endo, Hanae Iijima, Tomoko Kaida, Kazunori Miyata, Shuji Nakazaki, Takaaki Hayashi, Yasuhiko Hirami, Masato Akiyama, Chikashi Terao, Yukihide Momozawa, Koh-Hei Sonoda, Koji M. Nishiguchi, and Yasuhiro Ikeda.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Yoshito Koyanagi received research grants from the Japanese Retinitis Pigmentosa Society (JRPS), the Takayanagi Retina Research Award, and the Nasu Foundation. Satoshi Yokota received research grants (to Kobe City Eye Hospital) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED; JP21bk0104118h0001), Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Vision Care Inc. Yuji Inoue received lecture fees from Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Takaaki Hayashi received a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI Grant No. 24K12771). Yasuhiko Hirami received grants (to Kobe City Eye Hospital) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED; JP21bk0104118h0001), Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Vision Care Inc. Masato Akiyama received grants from Novartis Pharma K.K. (for glaucoma research), Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (for ocular tumor research), and Alcon (for ocular tumor research). He reported consulting fees for genetic testing for IRD from Sysmex. Furthermore, honoraria for lectures were received from Novartis Pharma K.K., Takeda Pharma Ltd., Senju Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Corporation, Kowa Co. Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical, Bayer Yakuhin, and Santen Pharmaceutical Corporation. He received support for attending meetings and travel from WAKAMOTO PHARMACEUTICAL CO. LTD., Novartis Pharma K.K. and Chugai Pharmaceutical. He is an endowed faculty member supported by NIDEK Co. Ltd. Koh-Hei Sonoda received grants (to his department) from Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Senju Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., HOYA Co., Ltd., WAKAMOTO Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., AMO Japan K.K., Kowa Company, Ltd., Alcon Japan Ltd, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Senju Pharmaceutical Corporation, and Sand Corporation. He received consulting fees from Santen Pharmaceutical Corporation, Senju Pharmaceutical Corporation, Japan Tobacco Inc., Chugai Pharmaceutical Corporation, Sand Corporation, and Riverfield Corporation. He received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from AMO Japan K.K., Novartis Pharma K.K., WAKAMOTO Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., NIDEK CO., LTD., Canon Marketing Japan Inc., TOPCON CO., LTD., Senju Pharmaceutical Corporation, Santen Pharmaceutical Corporation, Chugai Pharmaceutical Corporation, Bayer Corporation, Alcon Japan Ltd, Eisai Corporation, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Corporation, Ono Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Canon Marketing Japan, Viatoris Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, and Celltrion Healthcare Japan K.K. Koji M. Nishiguchi received funding from JCR Pharma Ltd for EYS gene therapy research, paid to his institution. He is a co-inventor of a pending patent (application number: 2022-030349) filed by National University Corporation Tokai National Higher Education and Research. The patent application, which is currently pending, pertains to gene therapy for the S1653Kfs mutation, an aspect discussed in the manuscript. Yasuhiro Ikeda received a grant from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (JP23ek0109632). Yusuke Murakami, Taro Kominami, Masatoshi Fukushima, Kensuke Goto, Kei Mizobuchi, Go Mawatari, Kaoruko Torii, Junya Ota, Daishi Okuda, Kohta Fujiwara, Hanayo Yamaga, Takahiro Hisai, Mikiko Endo, Hanae Iijima, Tomoko Kaida, Kazunori Miyata, Shuji Nakazaki, Chikashi Terao, and Yukihide Momozawa declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koyanagi, Y., Murakami, Y., Kominami, T. et al. Clinical characteristics of EYS-associated retinal dystrophy in 291 Japanese patients. npj Genom. Med. 11, 3 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-025-00541-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-025-00541-0